Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Psychosocial stress can be the cause or the consequence of hypertension.

OBJECTIVE:

To study the association between hypertension and anxiety or depression in adults from Hong Kong, China.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS:

Patients with diagnosed hypertension (n=197) were recruited to complete the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) questionnaire. The control group comprised 182 normotensive subjects recruited using random telephone numbers.

RESULTS:

The score in the anxiety subscale (HADS-A) of the HADS correlated with age (r= −0.23, P<0.001) and sex (r=0.11, P=0.042), and was found to be higher in women. The score in the depression subscale (HADS-D) correlated with age (r=0.17, P=0.003) and hypertension (r=0.12, P=0.039), but not with sex (r=0.02, P=0.68). When the control subjects were matched for sex and age with the subjects with hypertension, the mean HADS-A score was 5.51±0.41 in 113 hypertensive subjects and 4.38±0.39 in 113 normotensive subjects (P=0.047). The mean HADS-D score was 5.56±0.39 in the hypertensive and 4.76±0.32 in the normotensive subjects (P=0.11). Multiple regression analysis using data from both groups indicated that the HADS-A score was related to the HADS-D score (β=0.49, P<0.001), age (β= −0.25, P<0.001) and sex (β=0.12, P=0.01) (R2=0.28), whereas the HADS-D score was related to the HADS-A score (β=0.48, P<0.001), age (β=0.30, P<0.001), positive smoking status (β=0.13, P=0.004) and lack of exercise habit (β=0.12, P=0.008) (R2=0.31). Hypertension was related to waist circumference, history of parental hypertension and age (R2=0.38, P<0.001). Anxiety and depression scores were rejected as independent variables.

CONCLUSIONS:

Hypertension was associated with anxiety but not depression; however, age, history of parental hypertension and central obesity appeared to have a stronger association with hypertension in adults from Hong Kong.

Keywords: Anxiety, Blood pressure, Depression, Hypertension, Questionnaire, Telephone survey

There is an intricate relationship between physical health and psychological status. Anxiety and depression are known to have diverse effects on body functions. Because the cardiovascular system is regulated by the autonomic nervous system, emotional states may have a profound influence on the cardiovascular system, including blood pressure.

Many investigators have studied psychological factors that may lead to hypertension (1). Rutledge and Hogan (2) found that the risk of developing hypertension was approximately 8% higher among people who had psychological distress compared with those who had minimal distress. People suffering from either severe depression or anxiety were two to three times more likely to develop hypertension (3). A French study of the elderly in the community (4) revealed that hypertension was associated with anxiety but not depression. On the other hand, a longitudinal study of 6903 male-male twins (5) showed that hypertension was associated with depression, suggesting that there are common genetic factors that predispose individuals to hypertension and depression. Indeed, depressed persons have been shown to have increased ambulatory blood pressure compared with control subjects (6).

These results are still controversial because of a number of reports demonstrating the contrary. In a study by Friedman et al (7), the predictive significance of psychological factors was negligible in the causation of mild hypertension. In addition, Shinn et al (8) did not find a significant role for anxiety or depression in the development of hypertension.

In Asian countries, data on the association between hypertension and anxiety or depression are scarce. In China, hypertension affects approximately 100 million individuals (9). In Hong Kong, the prevalence of hypertension is approximately 20%, and 31% of patients who require long-term follow-up are hypertensive (10). Because hypertension is a common disease in the community, there is a need to investigate the prevalence of anxiety and depression in these patients. Anxiety and depression may predispose individuals to develop hypertension but may also be a consequence of the disease.

The objective of the present study was to examine the association between hypertension and anxiety or depression in adults from Hong Kong. The null hypothesis was that there was no difference in the degree of anxiety or depression in subjects with and without hypertension.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Hong Kong and Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (Hong Kong). One hundred seventy-three subjects with hypertension were recruited from the hypertension outpatient clinic of Queen Mary Hospital (Hong Kong), a university teaching hospital. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or higher and/or a diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg or higher occurring on more than two separate occasions or if the patient was on antihypertensive medication for the treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension. The exclusion criteria were subjects with secondary hypertension, with clinical depression or taking antidepressants, with clinical anxiety or taking anxiolytics, with other psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, and those who had been receiving any kind of treatment known to increase blood pressure or induce anxiety or depression. The participation rate was 97.2%. Reasons for nonparticipation were refusal (n=2), language barrier (n=1) and deafness (n=1). Of the 173 subjects with hypertension, five did not answer all of the questions.

The control group comprised normotensive subjects recruited from the general population using random telephone numbers. Household telephone numbers from a computer-generated list were used. The person who was interviewed in each household, who may not have been the same person answering the telephone, was determined using the Kish grid method (11), ie, the chosen subject’s seniority within the household was random. Altogether, 2556 randomly generated telephone numbers were used. From these telephone numbers, it was possible to contact 555 subjects, of whom 206 agreed to take part. The participation rate was 37.1%, which was in accordance with the expected response rate when using randomly generated telephone numbers in the Hong Kong region. Of the 349 nonrespondents, the sex was known for 204 subjects: 93 were men and 111 were women. The most common reason for not participating in the study was refusal. Among the respondents, two subjects did not answer all of the questions. There were 24 subjects in the telephone survey who were hypertensive and, therefore, they were not classified as normotensive (although, their inclusion would not have materially affected the overall Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS] scores in the control group). These subjects were included in the hypertensive group because they did not differ significantly from patients attending the hypertension clinic in terms of their anxiety subscale (HADS-A) (P=0.12) and depression subscale (HADS-D) (P=0.43) scores of the HADS. Therefore, the total number of hypertensive subjects was 197.

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Those attending the clinics were requested to sign a consent form. Subjects participating in the telephone survey gave verbal consent.

The blood pressure records of the subjects attending the hypertension clinic were reviewed to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension. For all subjects, a family history of hypertension, body weight, waist circumference, alcohol consumption, smoking status, physical activity, diabetes mellitus diagnosis and serum lipid levels were recorded. Each subject completed the Chinese version of the HADS questionnaire (12). Anxiety was defined as a score of 8 or higher in the HADS-A, with a sensitivity and specificity of approximately 0.80 (12,13). Depression was defined as a score of 8 or more in the HADS-D, with a sensitivity and specificity of approximately 0.80 (12,13).

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS Inc, USA). Subject characteristics of the normotensive and hypertensive subjects were compared using an unpaired Student’s t or χ2 test, where appropriate. HADS scores in the two groups were compared using the unpaired Student’s t test. Distributions of the scores were compared using the χ2 test. Correlation between two variables was determined using Spearman’s test. Stepwise multiple regression was used to identify independent variables predictive of the HADS-A and HADS-D scores. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify independent variables that were predictive of hypertension. Sex, age, weight, waist circumference, diabetes mellitus diagnosis, parental history of hypertension, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and HADS-A and HADS-D scores were tested as independent variables. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Anxiety, measured using the HADS-A, correlated with age (r=−0.23, P<0.001) and sex (r=0.11, P=0.042). HADS-A scores were higher in women than in men. Depression, measured using the HADS-D, correlated with age (r=0.17, P=0.003) and hypertension (r=0.12, P=0.039), but not with sex (r=0.02, P=0.68). Multiple regression analysis using data from both groups indicated that the HADS-A score was related to the HADS-D score (β=0.49, P<0.001), age (β=−0.25, P<0.001) and sex (β=0.12, P=0.01) (R2=0.28), whereas the HADS-D score was related to the HADS-A score (β=0.48, P<0.001), age (β=0.30, P<0.001), positive smoking status (β=0.13, P=0.004) and lack of exercise habit (β=0.12, P=0.008) (R2=0.31).

Because the HADS scores correlated with age and there was a significant difference in age between the patients with hypertension and the control subjects randomly recruited from the general population, further analysis was restricted to 226 age- and sex-matched hypertensive patients (n=113) and controls (n=113). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the subjects from the two groups. There were significant differences between the hypertensive and normotensive subjects in body weight, waist circumference, family history of hypertension and prevalence of diabetes. In the subjects with hypertension, the median time since the diagnosis of hypertension was eight years (range zero to 50 years).

TABLE 1.

Subject characteristics

| Characteristic | Normotensive (n=113) | Hypertensive (n=113) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male:female) | 55:58 | 57:56 | 0.79 |

| Age (years) | 50.1±12.8 | 50.1±12.6 | 1.00 |

| Weight (kg) | 60.3±12.3 | 69.9±13.2 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 76.0±9.5 | 83.8±11.1 | <0.001 |

| Family history of hypertension (%) | 46 | 71 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 3 | 11 | 0.01 |

| Regular smoking (%) | 16 | 17 | 0.83 |

| Regular drinking (%) | 4 | 9 | 0.18 |

| Regular exercise (%) | 56 | 60 | 0.54 |

Continuous data are expressed as mean ± SD.

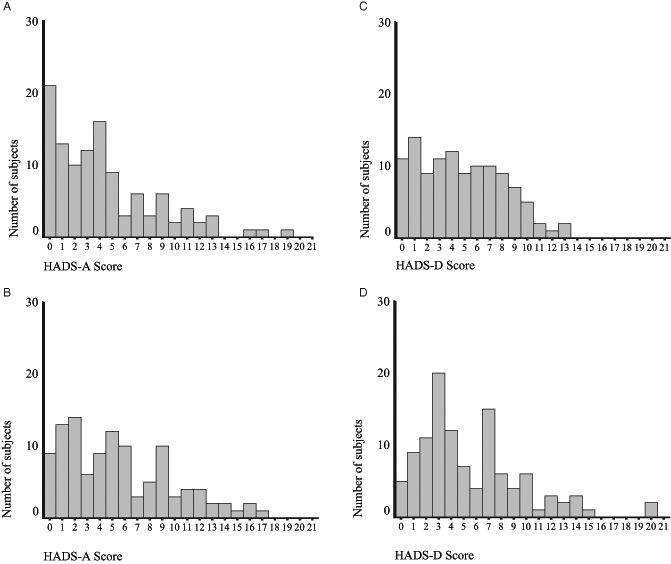

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the HADS-A and HADS-D scores in hypertensive and normotensive subjects. Table 2 shows the distribution of the scores in terms of normal, mild, moderate and severe anxiety or depression. There was no significant difference in the distribution of the HADS-A and HADS-D scores between normotensive and hypertensive groups using the χ2 test. The mean HADS-A score was 5.51±0.41 in the subjects with hypertension and 4.38±0.39 in the normotensive subjects; the difference in the mean scores was 1.13 (95% CI 0.17 to 2.24, P=0.047). The mean HADS-D score was 5.56±0.39 in the hypertensive and 4.76±0.32 in the normotensive subjects; the difference in mean scores was 0.8 (95% CI −0.19 to 1.79, P=0.11).

Figure 1).

The distribution of scores of the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A) in (A) normotensive and (B) hypertensive subjects, and of the depression subscale (HADS-D) of the HADS in (C) normotensive and (D) hypertensive subjects. The normotensive and hypertensive subjects were matched for age (n=113 per group)

TABLE 2.

Distribution of scores from the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in age- and sex-matched hypertensive (n=113) and control subjects (n=113)

|

HADS-A |

HADS-D |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Hypertensive | Control | Hypertensive | |

| Normal (0–7) (%) | 80 | 69 | 77 | 75 |

| Mild (8–10) (%) | 10 | 16 | 19 | 14 |

| Moderate (11–14) (%) | 8 | 11 | 5 | 8 |

| Severe (15–21) (%) | 3 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

The levels of anxiety or depression are given as level (range of scores). HADS-A Anxiety subscale of HADS; HADS-D Depression subscale of HADS

Logistic regression analysis of all subjects revealed that hypertension was related to waist circumference, history of parental hypertension and age (R2=0.38, P<0.001) (Table 3). Anxiety and depression scores were rejected as independent variables in conditional forward logistic regression analysis.

TABLE 3.

Logistic regression analysis with hypertension as the dependent variable

| Factor | OR (exp[B]) | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.04 | 1.02–1.07 | <0.001 |

| Parental history of hypertension | 3.49 | 1.99–6.09 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 1.09 | 1.06–1.12 | <0.001 |

| Constant | <0.001 |

DISCUSSION

There are not many studies of hypertension and anxiety or depression using validated psychometric questionnaires. In the present study, hypertensive subjects were more anxious than the general population. Although we cannot discount the possibility of anxiety arising from being labelled hypertensive, our results are consistent with the findings of studies in the elderly from France (4) and California (14). The sample size in the present study was not very large; thus, the results should be interpreted with a degree of caution.

Hypertensive subjects at first appeared to have a higher depression score compared with that of the control subjects, but this was largely explained by the older age of the hypertensive subjects. There was no significant difference between hypertensive and age-matched normotensive control subjects. The average age of the subjects was 50 years; however, the average age of hypertensive persons in the community is much higher (15). Among the elderly, depression may be more prevalent, and consequently, the relationship between hypertension and depression may be more pronounced. We found that the HADS-D score correlated with the HADS-A score, as previously reported in the literature (16). We also found that the HADS-D score was related to aging, positive smoking status and lack of exercise habit, which are known cardiovascular risk factors. Hence, a hypertensive patient with depression is at an additional cardiovascular risk and requires more attention to his or her physical and psychological health.

Multiple regression analysis showed that abdominal obesity, history of parental hypertension and age were predictors of hypertension, while anxiety and depression were not major factors associated with hypertension in adults from Hong Kong. Although causal inferences cannot be made from any cross-sectional study, the narrow CIs of the HADS-A and HADS-D scores allow us to be reasonably sure that neither anxiety nor depression was strongly associated with hypertension. Nevertheless, approximately one in four subjects in our study had abnormal HADS scores, indicating some degree of anxiety or depression. Therefore, the recognition of anxiety and depression is important in the clinical management of patients with hypertension, in addition to treatment with antihypertensive drugs. Addressing psychological problems may enhance the patient’s emotional well-being and quality of life.

We recognize that the environmental settings of the clinic and telephone survey were different. Nevertheless, the hypertensive and control groups completed the same questionnaire read to them by an investigator. Both groups were interviewed by the same team of investigators using a standardized protocol. Persons randomly selected from the general population were more willing to answer questions over the telephone than to come to the clinic in person; therefore, bringing control subjects to the clinic may introduce bias. The 24 subjects in the telephone survey who were hypertensive were not included in the control group, although their inclusion would not have materially affected the overall HADS scores of the control group. There was no significant difference in HADS-A or HADS-D scores between these 24 subjects and the patients from the hypertensive clinic.

In the telephone interview, information on waist measurement and blood pressure status (hypertensive or not) was given by the subject. Participants were not asked to provide actual blood pressure readings over the telephone because most people cannot accurately remember their most recent blood pressure readings; they may round them off or they may not know their blood pressure. In addition, blood pressure readings from the patients with hypertension were not useful for analysis because they are affected by antihypertensive treatment. We recognize that in a telephone survey of the general population, there would be subjects in the community with undiagnosed hypertension. If the study were confined to subjects who could visit the clinic, selection bias would be introduced, and even if it were possible, hypertension cannot be diagnosed in one visit. In our random telephone survey, 13% of the subjects reported that they were hypertensive. Because the prevalence of hypertension is 20% in the general population, approximately 7% of these subjects may have undiagnosed hypertension. And if the rule of halves applies, there could be 13% of subjects undiagnosed with hypertension. Nevertheless, the contamination bias is not serious and is outweighed by the advantage of having control values representative of the community.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study of individuals randomly selected from the community and patients from a hypertensive clinic demonstrated that women and younger subjects were more likely to be anxious, while older subjects were more likely to be depressed. Patients with hypertension had higher HADS-A scores compared with age- and sex-matched controls, whereas there was no significant difference in the HADS-D scores between the two groups. Therefore, we conclude that hypertension is associated with anxiety but not depression. Hypertension in adults from Hong Kong is related to age, parental history of hypertension and waist circumference. Neither anxiety nor depression had a strong association with hypertension.

Acknowledgments

The present study formed part of an undergraduate Health Care Project of the Department of Community Medicine, University of Hong Kong. FHK Ning set up the framework for data entry and analysis in SPSS. DYB Man performed part of the data analysis. RP Lee provided advice on the use of psychometric questionnaires.

REFERENCES

- 1.Markovitz JH, Jonas BS, Davidson K. Psychologic factors as precursors to hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2001;3:25–32. doi: 10.1007/s11906-001-0074-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutledge T, Hogan BE. A quantitative review of prospective evidence linking psychological factors with hypertension development. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:758–66. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000031578.42041.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonas BS, Franks P, Ingram DD. Are symptoms of anxiety and depression risk factors for hypertension? Longitudinal evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Arch Fam Med. 1997;6:43–9. doi: 10.1001/archfami.6.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paterniti S, Alperovitch A, Ducimetiere P, Dealberto MJ, Lepine JP, Bisserbe JC. Anxiety but not depression is associated with elevated blood pressure in a community group of French elderly. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:77–83. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199901000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scherrer JF, Xian H, Bucholz KK, et al. A twin study of depression symptoms, hypertension, and heart disease in middle-aged men. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:548–57. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000077507.29863.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lederbogen F, Gernoth C, Hamann B, Kniest A, Heuser I, Deuschle M. Circadian blood pressure regulation in hospitalized depressed patients and non-depressed comparison subjects. Blood Press Monit. 2003;8:71–6. doi: 10.1097/00126097-200304000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman R, Schwartz JE, Schnall PL, et al. Psychological variables in hypertension: Relationship to casual or ambulatory blood pressure in men. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:19–31. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200101000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shinn EH, Poston WS, Kimball KT, St Jeor ST, Foreyt JP. Blood pressure and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A prospective study. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:660–4. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)01304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu D, Reynolds K, Wu X, et al. InterASIA Collaborative Group The International Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease in ASIA. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China. Hypertension. 2002;40:920–7. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000040263.94619.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health Annual Report 1999–2000Department of Health, Hong Kong, 2001<www.info.gov.hk/dh/ar9900.htm> (Version current at March 23, 2005).

- 11.Kish L. A procedure for objective respondent selection within the household. J Am Stat Assoc. 1949;44:380–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leung CM, Wing YK, Kwong PK, Lo A, Shum K. Validation of the Chinese-Cantonese version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale and comparison with the Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;100:456–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta KM, Simonsick EM, Penninx BW, et al. Prevalence and correlates of anxiety symptoms in well-functioning older adults: Findings from the health aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:499–504. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janus ED, Hong Kong Cardiovascular Risk Factor Prevalence Study 1996–1996 . Hong Kong: Queen Mary Hospital; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiller W, Zazudig M, Bose MV. The overlap between depression and anxiety on different levels of psychopathology. J Affect Disord. 1989;16:223–31. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(89)90077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]