Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Angiotensin II plays a central role in the development of congestive heart failure. Among its many actions linked to heart failure is the promotion of ventricular remodelling. Although the growth component of ventricular remodelling may initially be compensatory, the apoptotic component is associated with a decline in contractile function. Therefore, the uncoupling of angiotensin II-induced apoptosis from its other actions may prove to be clinically beneficial. However, the development of proper therapy awaits information on the mechanism underlying angiotensin II-induced apoptosis.

OBJECTIVES:

To establish the signalling pathway responsible for angiotensin II-induced apoptosis.

METHODS:

Isolated neonatal cardiomyocytes were incubated for several hours with medium containing 1 nM angiotensin II. The extent of angiotensin II-mediated mitochondrial DNA damage was assessed by Southern blot analysis, and the expression of electron transport proteins was evaluated by Western blot analysis. The effect of cyclosporin A on terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated 2′-deoxyuridine-5′-triphosphate-biotin nick end labelling and cytosolic cytochrome c content were used to monitor mitochondrial permeability transition pore involvement in angiotensin II-induced apoptosis.

RESULTS:

Angiotensin II caused significant DNA damage, an effect associated with the downregulation of NADH dehydrogenase subunit 5, a component of complex 1 of the electron transport chain. Angiotensin II-mediated apoptosis, as assessed by cytochrome c release and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated 2′-deoxyuridine-5′-triphosphate-biotin nick end labelling, was largely blocked by the mitochondrial permeability transition pore antagonist, cyclosporin A.

CONCLUSIONS:

Angiotensin II-induced apoptosis proceeds through a signalling pathway involving DNA damage, reduced rates of electron transport and the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Thus, an inhibitor of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore would largely block angiotensin II-induced apoptosis without affecting the other actions of angiotensin II.

Keywords: Angiotensin II, Apoptosis, DNA damage, Permeability transition pore

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers are the mainstay for the treatment of congestive heart failure. Traditionally, it has been argued that either a reduction in angiotensin II levels or impairment in angiotensin II action improves cardiac function through a reduction in afterload and an increase in renal blood flow (1). However, several studies reveal that angiotensin II also promotes apoptosis in normal and diseased hearts and cardiomyocytes (2–6). This may be an underappreciated consequence of angiotensin II’s role in heart failure. According to Feuerstein et al (7), the loss of myocytes in the diseased heart is a determinant of heart failure severity. Moreover, the progressive deterioration in mechanical performance in heart failure may be caused by the loss of viable cardiomyocytes (8). Therefore, clarification of the role of angiotensin II-induced apoptosis in the development of heart failure seems warranted. Additionally, the mechanism underlying angiotensin II-induced apoptosis is of therapeutic interest.

One of the pathways implicated in angiotensin II-induced apoptosis is the p53-Bax signalling pathway (9,10). Grishko et al (10) have suggested that activation of NADPH oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase, with subsequent generation of peroxynitrite, causes DNA damage that stimulates the p53-Bax signalling pathway. However, recent studies (11,12) have suggested that mitochondrial DNA damage can also cause apoptosis through the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the involvement of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in angiotensin II-induced apoptosis.

METHODS

Cardiomyocyte preparation and incubation conditions

Neonatal cardiomyocytes were obtained from two-day-old Wistar rats. After dissociation, the cells were preplated on plastic culture dishes for 90 min at 37°C to allow for nonmyocyte attachment. The unattached cells were then suspended in minimum essential medium containing 10% newborn calf serum and 0.1 mM 5′-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine. The isolated cardiomyocytes were plated either on glass coverslips or polystyrene-treated petri dishes at a density of approximately 12×106 cells/dish (10 cm diameter). After an overnight incubation to allow the attachment of viable cardiomyocytes, the cells were cultured in serum-free medium containing minimum essential medium. Cells were then subjected to the appropriate experimental protocol, which consisted of a further incubation for 6 h with medium supplemented with either 1 nM angiotensin II or 1 nM angiotensin II plus 200 nM cyclosporin A. Following incubation, the cells were used in the analysis of apoptosis (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated 2′-deoxyuridine-5′-triphosphate-biotin nick end labelling assay), mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase subunit 5 (ND5) content (Western blot), cytosolic cytochrome c content (Western blot) or DNA damage (Southern blot).

The terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated 2′-deoxyuridine-5′-triphosphate-biotin nick end labelling procedure

The cell specimens were fixed in 4% formaldehyde (in phosphate buffered saline [1×]) for 15 min at room temperature and resuspended in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 15 min. The Klenow-FragEL DNA Fragmentation Detection Kit (Calbiochem, USA) was then used to assess DNA breaks in apoptotic nuclei. Specimens were rehydrated in TBS and incubated with 20 μg/mL proteinase K for 20 min. Following rehydration in TBS, the specimens were incubated for 5 min with 3% H2O2 to inactivate endogenous peroxidases, and rehydrated again in TBS. Specimens were then incubated for approximately 20 min with Klenow equilibration buffer (1×). After removing the Klenow equilibration buffer, specimens were incubated for 90 min at 37°C with Klenow labelling reaction mixture. The labelling reaction was terminated by rehydrating the specimens in TBS and then incubating for 5 min with stop solution. Specimens were rehydrated in TBS and incubated for 10 min at room temperature with blocking buffer. After removing the blocking buffer, specimens were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with peroxidase-streptavidin (1×) conjugate. Specimens were rehydrated in TBS and incubated for 15 min at room temperature with 3,3-diaminobenzidine and 0.6 mg of H2O2-urea solution and rinsed with distilled H2O. Specimens were counter-stained with methyl green for 3 min. Colour was fixed by immersing the specimens in 100% ethanol and then xylene. Five separate fields in the light microscope were examined for dark brown (apoptotic) and green (normal) nuclei.

Detection of mitochondrial DNA damage using quantitative Southern blots

Isolated neonatal cardiomyocytes were exposed to 1 nM angiotensin II for various periods of time. After the cells were lysed, high-molecular-weight DNA was phenol extracted, precipitated with ammonium acetate and then exposed to two volumes of cold ethanol. The DNA samples were resuspended in water and then digested with the restriction endonuclease BamHII (10 U/μg DNA) at the same time it was treated with DNase-free RNase (approximately 1.0/mL) for 12 h to 16 h at 37°C. After digestion, the samples were precipitated with ammonium acetate and resuspended in Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA; pH 8.0). The DNA was precisely quantified using a Hoefer TKO 100 Mini-Fluorometer and a TKO standards kit (Hoefer Scientific Instruments, USA). Samples containing 5 μg DNA were heated at 65°C for 20 min and then cooled at room temperature for an additional 20 min. After NaOH was added to a final concentration of 0.1 M, samples were incubated for 15 min at 37°C. This produced single-strand breaks at any abasic or sugar-modified site in the DNA. Samples were then combined with 5 μL of loading dye, loaded onto a 0.6% alkaline agarose gel, and electrophoresed at 30 V (1.5 V/cm gel length) for 16 h in an alkaline buffer consisting of 23 mM NaOH and 1 mM EDTA. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide to confirm equal loading. After the gels were washed, DNA was transferred to a Zeta-Probe GT nylon membrane (Bio-Rad, USA). The membranes were crosslinked and hybridized with a 32P-labelled rat mitochondrial DNA-specific polymerase chain reaction-generated probe. Hybridization and subsequent washes were performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. DNA damage was assessed as follows:

Western blot analyses

Cellular content of ND5 and cytochrome c were determined by Western blot analysis. The cells were washed twice in buffer containing: 250 mmol/L sucrose, 10 mmol/L triethanolamine, pH 7.6 at room temperature. Next, cells were lysed in ice-cold isolation buffer (pH 7.25 at 4°C) with the following composition: 150 mmol/L mannitol, 2 mmol/L sucrose, 5 mmol/L HEPES, 1 mmol/L EDTA and protein protease inhibitors (a 1:100 dilution of protease inhibitor cocktail set III, 1% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 100 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate). The homogenate was centrifuged (Micromax RF, Thermo EC, USA) at 800 g for 6 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was retrieved and centrifuged again at 12,000 g for 15 min. The pellet was defined as the mitochondrial fraction and used to determine ND5 content. The supernatant was defined as the cytosolic fraction and used to determine cytochrome c content. Protein concentration was determined by the Lowry method using bovine serum albumin as a standard. During Western blot analysis, the samples were subjected to 13% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, where they were blocked. After incubation with the appropriate antibody the membranes were washed and then incubated with a secondary antibody. The Western blots were detected by the enhanced chemiluminescence reaction.

RESULTS

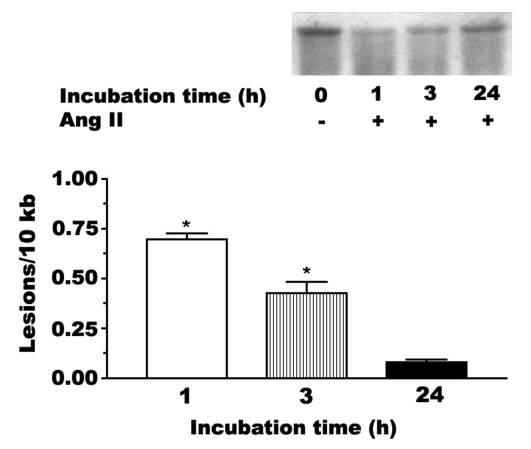

Angiotensin II (1 nM) mediates a rapid modification of mitochondrial DNA, with the frequency of modification after 1 h of exposure being approximately 0.75 sites/10 kb of DNA (Figure 1). The degree of DNA damage is largely reversed by 24 h of angiotensin II exposure, suggesting that repair enzymes reverse the damage to both purines and pyrimidines.

Figure 1).

Mitochondrial DNA damage mediated by angiotensin II (Ang II). Neonatal cardiomyocytes were incubated for various periods of time with medium containing 1 nM Ang II. High-molecular-weight DNA was isolated and digested to completion with BamHII. The samples were exposed to 0.1 M NaOH before electrophoresis on a 0.6% agarose gel. Shown is a representative Southern blot of the prominent 10 kb band of mitochondrial DNA. The reduction in the intensity of the 10 kb band is indicative of DNA fragmentation. The data are also expressed as the number of lesions per 10 kb. Although not shown, control samples contained no apparent lesion. Values shown represent the mean ± SEM of three to five preparations. *A significant difference between the Ang II-treated and control cells (P<0.05)

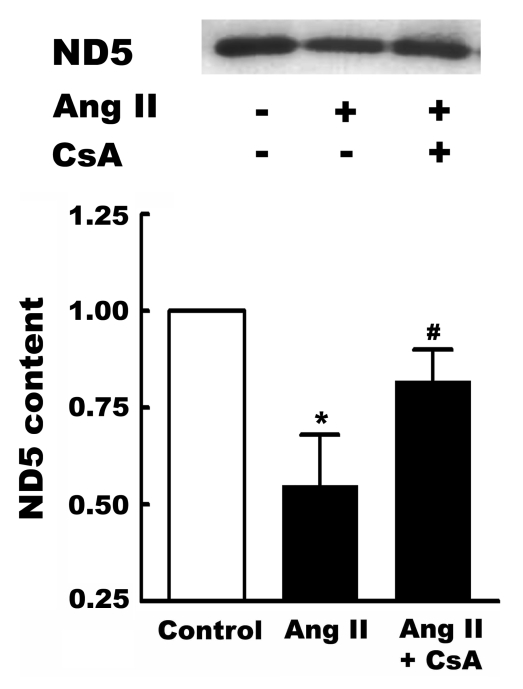

Associated with the oxidation of DNA is a downregulation in the level of ND5, a component of complex 1 of the electron transport chain. Interestingly, inhibiting the formation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore with cyclosporin A partially prevents the reduction in ND5 levels (Figure 2).

Figure 2).

Effect of angiotensin II (Ang II) on NADH dehydrogenase subunit 5 (ND5) content. Neonatal cardiomyocytes were incubated for three days in control medium. On the third day, some cells were treated for 6 h with medium containing either 1 nM Ang II, or 1 nM Ang II and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore inhibitor, cyclosporin A (CsA, 200 nM). Following treatment, the cardiomyocytes were harvested, mitochondria isolated and Western blots of ND5 obtained. Shown above is a representative Western blot, with the means ± SEM of five different preparations shown below. *A significant difference between the Ang II-treated and control cells (P<0.05); #A significant difference between the CsA plus Ang II and the Ang II groups (P<0.05)

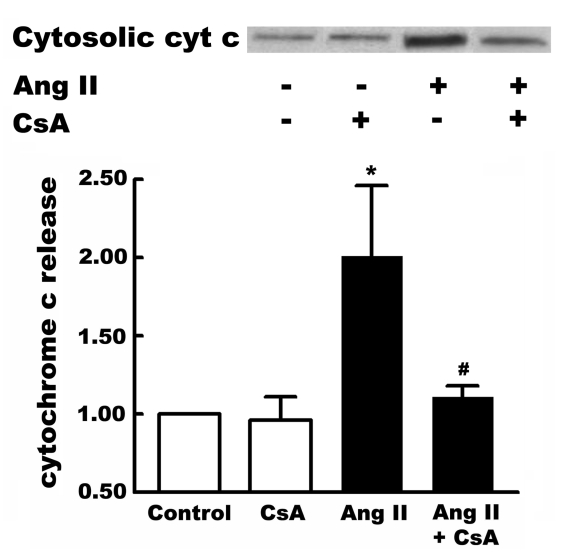

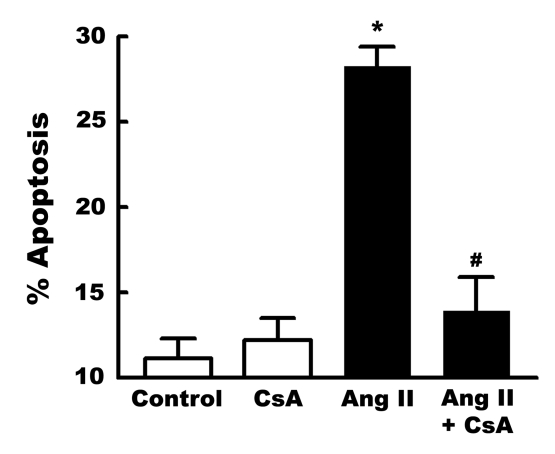

Zhang et al (13) and Mott et al (11) have proposed that mitochondrial DNA damage promotes apoptosis through the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Consistent with this hypothesis, angiotensin II was found to promote cytochrome c release, an effect prevented by cyclosporin A (Figure 3). Cyclosporin A also blocked angiotensin II-induced apoptosis (Figure 4).

Figure 3).

Effect of cyclosporin A (CsA) on angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced cytochrome c (cyt c) release. Neonatal cardiomyocytes were incubated for three days in control medium. On the third day, some cells were treated for 6 h with either 1 nM Ang II, or 1 nM Ang II and CsA (200 nM). Following treatment, cells were harvested and the cytosolic fraction isolated. The cytosolic content of cyt c was determined by Western blot analysis. Shown above is a representative gel of cytosolic cyt c content. Values shown below represent means ± SEM of five preparations. *A significant difference between the Ang II-treated and control cells (P<0.05); #A significant difference between the Ang II plus CsA and the Ang II groups (P<0.05)

Figure 4).

Inhibition of angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced apoptosis by cyclosporin A (CsA). Neonatal cardiomyocytes were incubated for three days with control medium. Some cells were incubated for 6 h with medium containing either 1 nM Ang II or, 1 nM Ang II and 200 nM CsA. Following treatment, cell death was assessed by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated 2′-deoxyuridine-5′-triphosphate-biotin nick end labelling staining. Values shown represent means ± SEM of five preparations. *A significant difference between the Ang II-treated and control cells (P<0.05). #A significant difference between the Ang II plus CsA and the Ang II groups (P<0.05)

DISCUSSION

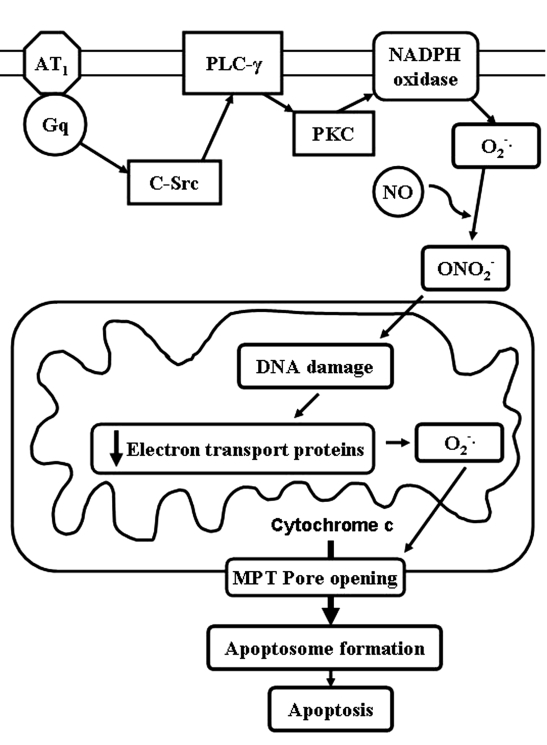

Figure 5 shows a scheme for angiotensin II-induced apoptosis. One of the earliest detectable events in angiotensin II signalling is the activation of c-Src, which stimulates phospholipase C activity. Protein kinase C then becomes activated which, in turn, activates NADPH oxidase, an important source of super-oxide. Following the activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase, superoxide and nitric oxide react to form peroxynitrite, an oxidant that readily reacts with DNA. In response to the resulting DNA damage, the expression of key mitochondrial proteins is downregulated. The flow of electrons through the electron transport chain slows, resulting in a diversion of electrons to oxygen. The antioxidant defense system is overwhelmed and severe oxidative damage ensues. Upon oxidation of the adenine nucleotide translocator (14), the mitochondrial permeability transition pore forms and cytochrome c is released. This series of events activates the caspase cascade and triggers apoptosis.

Figure 5).

Scheme of angiotensin II-induced apoptosis. AT1 Angiotensin II type 1 receptor; MPT Mitochondrial permeability transition; NO Nitric oxide; ONO2− Peroxynitrite; PKC Protein kinase C; PLC-γ Phospholipase C-gamma

Ide et al (12) have proposed a similar scheme for the progression of left ventricular remodelling and heart failure following DNA damage. They propose that the generation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species can trigger a vicious cycle of mitochondrial functional decline that leads to further reactive oxygen species generation. It begins with oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA, causing a reduction in mitochondrial transcript levels. As electron transport slows, the generation of reactive oxygen species is enhanced which, in turn, causes further DNA damage and additional damage to the electron transport chain, including direct inactivation of iron-sulfur clusters. This catastrophic generation of free radicals leads to cell death via apoptosis. Consistent with the present study and the scheme proposed by Ide et al (12), Mott et al (11) found that cardiac disease linked to random mitochondrial DNA mutation is prevented by cyclosporin A. Moreover, mice with an average of two point mutations per mitochondrial genome develop severe dilated cardiomyopathy, a condition associated with mitochondrial cytochrome c release and activation of apoptosis (13).

Grishko et al (10) have previously shown that angiotensin II, which shows increasing levels during heart failure, causes oxidative DNA damage; this was proposed to cause apoptosis through the activation of the p53-Bax pathway. However, the present study shows that angiotensin II also appears to activate the catastrophic cascade proposed by Ide et al (12). In addition to causing mitochondrial DNA damage, it is likely that multiple components of the electron transport chain are downregulated. Although the p53-Bax pathway promotes apoptosis through the release of cytochrome c, in the present study the release of cytochrome c was substantially blocked by an inhibitor of mitochondrial permeability transition pore formation. The inhibitor, cyclosporin A, also prevented angiotensin II-induced apoptosis. Therefore, although angiotensin II stimulates the p53-Bax pathway in the neonatal cardiomyocyte, the major cause of death following exposure to 1.0 nM angiotensin II appears to involve the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore.

Identification of the signalling pathway responsible for angiotensin II-induced apoptosis may have clinical implications. The upregulation of the renin-angiotensin II system in the failing heart is a compensatory response to the decrease in cardiac output. Therefore, it is not surprising that some of the events promoted by angiotensin II improve contractile function. However, other events, such as apoptosis, accelerate the onset of severe heart failure. Therefore, the therapeutic outcome might improve if one could prevent apoptosis and other damaging events while preserving the advantageous events of angiotensin II. The present study suggests that inhibitors of mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening may specifically eliminate one of the detrimental effects of angiotensin II.

Acknowledgments

Funded in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (HL-63723).

REFERENCES

- 1.Kelly RA, Smith TW. Pharmacological treatment of heart failure. In: Hardman JG, Limbrid LE, Molinoff PB, Ruddon RW, Gilman AG, editors. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996. pp. 809–38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cigola E, Kajstura J, Li B, Meggs LG, Anversa P. Angiotensin II activates programmed myocyte cell death in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 1997;231:363–71. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goussev A, Sharov VG, Shimoyama H, et al. Effects of ACE inhibition on cardiomyocyte apoptosis in dogs with heart failure. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H626–31. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.2.H626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiordaliso F, Li B, Latini R, et al. Myocyte cell death in streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats is angiotensin II-dependent. Lab Invest. 2000;80:513–27. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frustaci A, Kajstura J, Chimenti C, et al. Myocardial cell death in human diabetes. Circ Res. 2000;87:1123–32. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.12.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravassa S, Fortuno MA, Gonzalez A, et al. Mechanisms of increased susceptibility to angiotensin II-induced apoptosis in ventricular cardiomyocytes of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2000;36:1065–71. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.6.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feuerstein G, Ruffolo RR, Jr, Yue TL. Apoptosis and congestive heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1997;7:249–55. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(97)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharov VG, Sabbah HN, Shimoyama H, Goussev AV, Lesch M, Goldstein S. Evidence of cardiocyte apoptosis in myocardium of dogs with chronic heart failure. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:141–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diep QN, El Mabrouk M, Yue P, Schiffrin EL. Effect of AT(1) receptor blockade on cardiac apoptosis in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1635–41. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00984.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grishko V, Pastukh V, Solodushko V, Gillespie M, Azuma J, Schaffer S. Apoptotic cascade initiated by angiotensin II in neonatal cardiomyocytes: Role of DNA damage. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H2364–72. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00408.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mott JL, Zhang D, Freeman JC, Mikolajczak P, Chang SW, Zassenhaus HP. Cardiac disease due to random mitochondrial DNA mutations is prevented by cyclosporin A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319:1210–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ide T, Tsutsui H, Hayashidani S, et al. Mitochondrial DNA damage and dysfunction associated with oxidative stress in failing heart after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2001;88:529–35. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.5.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang D, Mott JL, Farrar P, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations activate the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and cause dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:147–57. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00695-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vieira HL, Belzacq AS, Haouzi D, et al. The adenine nucleotide translocator: A target of nitric oxide, peroxynitrite, and 4-hydroxynonenal. Oncogene. 2001;20:4305–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]