Abstract

Cancer/testis (CT) genes are predominantly expressed in human germ line cells, but not somatic tissues, and frequently become activated in different cancer types. Several CT antigens have already proved to be useful biomarkers and are promising targets for therapeutic cancer vaccines. The aim of the present study was to investigate the expression of CT antigens in breast cancer. Using previously generated massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) data, together with 9 publicly available gene expression datasets, the expression pattern of CT antigens located on the X chromosome (CT-X) was interrogated. Whereas a minority of unselected breast cancers was found to contain CT-X transcripts, a significantly higher expression frequency was detected in estrogen and progesterone receptor (ER) negative breast cancer cell lines and primary breast carcinomas. A coordinated pattern of CT-X antigen expression was observed, with MAGEA and NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B being the most prevalent antigens. Immunohistochemical staining confirmed the correlation of CT-X antigen expression and ER negativity in breast tumors and demonstrated a trend for their coexpression with basal cell markers. Because of the limited therapeutic options for ER-negative breast cancers, vaccines based on CT-X antigens might prove to be useful.

Keywords: cancer/testis antigens, estrogen receptor, therapy

Cancer/testis (CT) antigens are encoded by a unique group of genes that are predominantly expressed in human germ line cells, have little or no expression in somatic adult tissues, but become aberrantly activated in various malignancies (1). A total of 153 CT antigens has been described to date and are compiled in the CT database (www.cta.lncc.br/) (2, 3). Of these antigens, 83 are encoded by multigene families located on the X-chromosome and are referred to as the CT-X antigens (1). Although their possible involvement in chromosomal recombination, transcription, translation and signaling has been proposed, the physiological function of the great majority of CT-X antigens remains poorly elucidated (1, 4).

The expression of CT-X antigens varies greatly between tumor types, being most frequent in melanomas, bladder, non-small cell lung, ovarian, and hepatocellular carcinomas. The occurrence of CT-X antigens is uncommon in renal, colon, and gastric cancers (4). Where present, CT-X expression is associated with a poorer outcome and tends to be more frequent in higher grade lesions and advanced disease (5–8).

The combination of their restricted expression, and in some cases potent immunogenicity, has led to intense research into their utilization in therapeutic vaccines (9). Clinical trials of vaccines containing the CT-X antigens MAGEA and NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B are underway in patients with several cancers, including those of the lung, ovary, and melanoma (10–16).

Relatively few studies have explored the expression pattern of CT-X antigens in breast cancer and the few cases studied to date have focused on NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B (17–21). The objective of the present study was to undertake a more comprehensive analysis of CT-X antigen expression in primary breast cancer in the context of clinicopathological parameters. The results point to a restricted expression of members of the MAGEA and NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B gene families, primarily in ER negative tumors, some of which belong to the basal phenotype. Such lesions have a poorer prognosis for which, currently, therapeutic options are limited. CT-X-based immunotherapy strategies may thus represent an important therapeutic option for patients with these subtypes of breast tumors.

Results

Detection of CT-X Antigen Expression in Massively Parallel Signature Sequencing Data.

As an initial step in exploring CT-X antigen expression in breast cancer, we interrogated our previously published MPSS data (22). These data were derived from a pool of normal human breast luminal epithelial cells, a pool of predominantly ER-positive epithelial enriched primary breast tumors and 4 breast epithelial cell lines (22, 23). Sequence tags corresponding to 6 of the 83 CT-X antigens, including those for MAGEA (1,646 transcripts per million [tpm]), CSAG2 (680 tpm), CT45 (263 tpm), PASD1 (24 tpm), CSAG1 (15 tpm), and FMR1NB/NY-SAR-35 (11 tpm), were detected in only one sample, an ER-negative breast cell line BT20.

CT-X Antigen Expression in Breast Cancer Gene Expression Studies.

To further examine the possible relationship of CT-X expression with ER status, a list of 66 Affymetrix probe sets identifying 65 different CT-X-encoding genes was prepared (supporting information (SI) Table S1). Nine published microarray-based gene expression datasets derived from a total of 1,259 primary breast tumors and 51 breast cancer cell lines were available, and the ER status was known in most. Four hundred three of 1,310 samples were ER-negative (Table 1). Using the HG-U133A platform, we interrogated for each dataset gene expression patterns differentiating between ER-negative and ER-positive samples. Applying multiple testing controls, a P value cut-off of 0.05 and a 2-fold change filter, this analysis identified a set of 147 probe sets (131 genes) that showed significant differential expression between ER-negative and ER-positive breast tumors in at least 5 of the 9 datasets investigated. This list represents the ER specific expression (ERSE) set (Table S2). Many of the ERSE genes have previously been identified as differentially expressed in breast tumors in an ER status-dependent manner, or to be direct ER target genes (24–26).

Table 1.

Datasets used in this study

| Name | Accession no. | Samples |

Available annotations |

Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERneg | ERpos | Unknown | ER | PR | p53 | HER2 | |||

| Boersma | GSE5847 | 26 | 21 | 1 | Yes | No | No | No | 28 |

| Desmedt | GSE7390 | 64 | 134 | — | Yes | No | No | No | 46 |

| Doane | Website* | 42 | 57 | — | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 30 |

| Hess | Website† | 51 | 82 | — | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 29 |

| Ivshina | GSE4922 | 34 | 211 | 4 | Yes | No | Yes | No | 44 |

| Minn | GSE2603 | 42 | 57 | 22 | Yes | No | No | Yes | 31 |

| Neve | E-TABM-157 | 33 | 18 | — | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 27 |

| Sotiriou | GSE2990 | 34 | 85 | 6 | Yes | No | No | No | 47 |

| Wang | GSE2034 | 77 | 209 | — | Yes | No | No | No | 45 |

| vandeVijver | Website‡ | 69 | 226 | — | Yes | No | No | No | 34 |

The ERSE set was used to cluster the samples in each dataset (Fig. S1), confirming that ER status annotation was consistent in each dataset and that a CT-X-specific analysis would probably not be confounded by extraneous errors of annotation or data gathering. For each dataset, CT-X gene expression patterns were assessed for their relationship with ER status. This analysis used an identical test as was used to find the ERSE, except only the CT-X genes were tested and no fold-change filter was applied. The data are displayed as a summary (Table 2) and from the context of individual datasets (Tables S3–S11). To examine the enrichment of CT-X in the ER-negative tumors, we clustered the breast tumor datasets using the normalized CT-X expression data (Fig. 1). This analysis shows that relatively few CT-X genes are strongly expressed in breast cancer samples. For 3 datasets [Neve (27), Boersma (28), and Hess (29)], no statistically significant associations were found until multiple testing controls were subtracted from the analysis. The genes encoding CTAG1A/CTAG1B and CTAG2 (NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B family) showed the most consistent relationship with ER status (Table 2 and Fig. 2), being preferentially expressed in ER-negative samples (median adjusted P value <0.006). Other CT-X antigens showed consistent, but ultimately non-significant, relationships with ER status–notably MAGEA3 and MAGEA6 (Tables S3–S11).

Table 2.

ER status-specific CT-X gene expression (summary)

| Probe set | Gene symbol | Median P value |

|---|---|---|

| 211674_x_at | CTAG1A CTAG1B | 0.005 |

| 210546_x_at | CTAG1A CTAG1B | 0.005 |

| 215733_x_at | CTAG2 | 0.005 |

| 217339_x_at | CTAG1A CTAG1B | 0.006 |

| 209942_x_at | MAGEA3 | 0.154 |

| 220325_at | TAF7L | 0.239 |

| 214612_x_at | MAGEA6 | 0.263 |

| 219702_at | PLAC1 | 0.274 |

| 205564_at | PAGE4 | 0.314 |

| 214254_at | MAGEA4 | 0.317 |

| 206626_x_at | SSX1 | 0.317 |

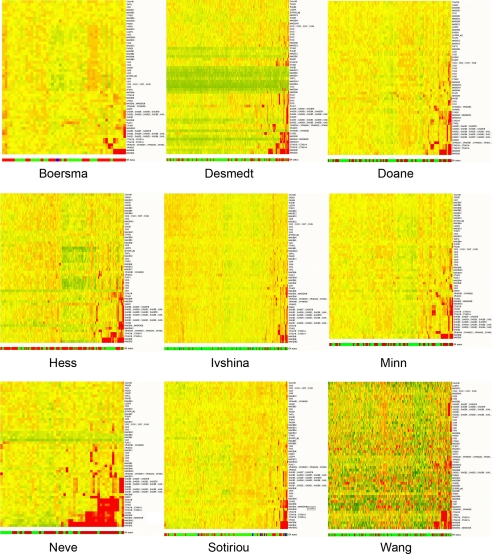

Fig. 1.

CT-X gene expression in breast cancer. Normalized gene expression data for CT-X genes were used to cluster breast cancer samples. Samples are arranged as columns and CT-X antigens in rows. Expression levels are pseudocolored, red indicating transcript levels above the median for that probe set across all samples and green below the median. The bar below each heatmap indicates the ER-negative (red) and ER-positive (green) status of the samples.

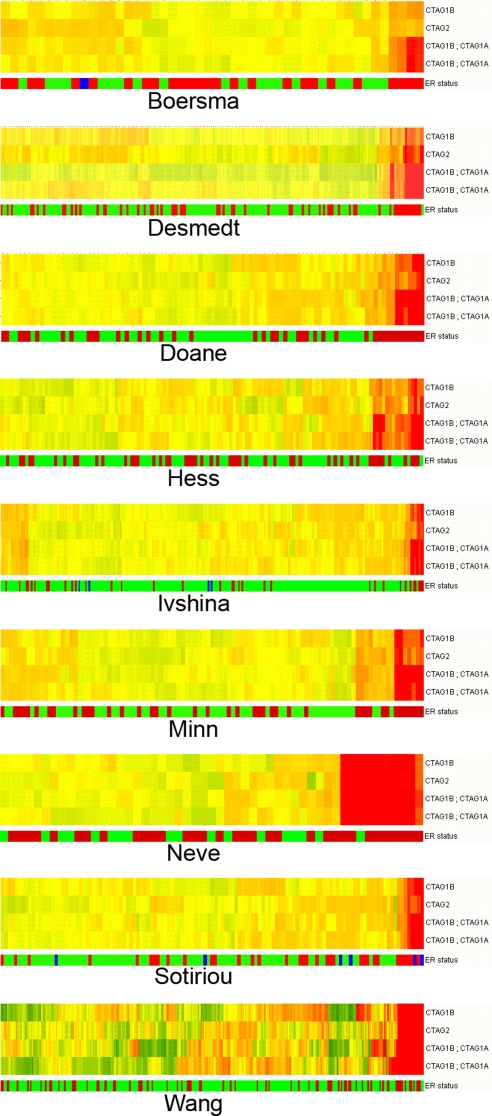

Fig. 2.

NY-ESO-1 gene expression in breast cancer. Normalized gene expression data for NY-ESO-1 genes were used to cluster breast cancer samples, highlighting the association that NY-ESO-1 genes have with ER-negative samples. Samples are arranged as columns and CT-X antigens in rows. Expression levels are pseudocolored, red indicating transcript levels above the median for that probe set across all samples and green below the median. The bar below each heatmap indicates the ER-negative (red) and ER-positive (green) status of the samples.

A similar analysis was performed for examining the correlation of CT-X expression and PR status, p53 mutation and HER2 status where available (Table 1). For each metric, the complete datasets of the above mentioned 9 breast tumor cohorts were interrogated for a significant relationship with metric status, and probe sets with less than a 2-fold change were discarded. This analysis was repeated for the CT-X antigen list (Table S1). There is a very strong overlap between the Doane (30) and Minn (31) 2-fold PR significant lists (137 probe sets, PRSE) (Table S12). The PRSE list also shared 105 probe sets in common with the ERSE list (P value <0.001), confirming that PR and ER status-specific gene expression patterns are tightly linked. In the Minn (31) dataset, 3 CT-X antigens (MAGEA6, MAGEA3 and MAGEA9) showed PR status-specific gene expression, but none of these showed a >2-fold differential expression. No consistent, significant relationship was detected between CT-X antigens and any of the 3 metrics examined.

Table 3 shows the fraction of ER-negative samples that expresses increased levels of CT-X antigens. In this series of 403 ER-negative primary breast cancers, members of the MAGEA and NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B families are expressed in 38.9% and 20.1% of the cases, respectively. Forty-four percent of the ER-negative tumors express members of either MAGEA or NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B families.

Table 3.

Fraction of ER-negative samples expressing increased levels of CT-X genes*

| Probe set | Gene symbol | Criteria I† | Criteria II‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 209942_x_at | MAGEA3 | 26.1% | 26.7% |

| 214612_x_at | MAGEA6 | 23.9% | 25.8% |

| 211674_x_at | CTAG1B; CTAG1A | 18.4% | 20.4% |

| 210546_x_at | CTAG1B; CTAG1A | 17.1% | 20.2% |

| 210467_x_at | MAGEA12 | 15.8% | 18.5% |

| 217339_x_at | CTAG1B | 15.0% | 19.6% |

| 215733_x_at | CTAG2 | 14.1% | 17.8% |

| 220445_s_at | CSAG2 | 14.1% | 17.4% |

| 214603_at | MAGEA2; MAGEA2B | 13.2% | 14.5% |

| 214642_x_at | MAGEA5 | 9.4% | 15.6% |

| 214254_at | MAGEA4 | 8.5% | 7.7% |

| 210503_at | MAGEA11 | 7.7% | 6.7% |

| 210437_at | MAGEA9 | 7.3% | 8.6% |

Calculated using 9 separate datasets (Table 1).

*Top 13 probes.

†Average percentage of ER-negative samples with >2-fold above mean expression level of all genes.

‡Average percentage of ER-negative samples in which expression is in the top tenth percentile of all genes.

CT-X Antigen Expression in Molecular Subtypes of Breast Cancers.

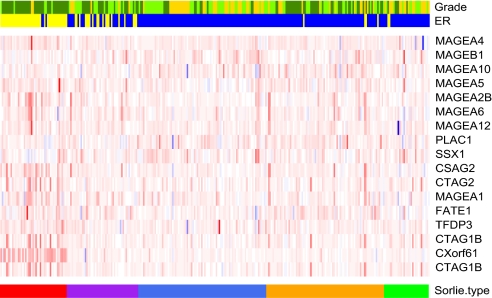

Using molecular profiling, breast cancers can be subdivided into luminal, HER2-positive, basal-like and so-called normal breast-like tumors (32, 33). We were able to evaluate whether the expression of CT-X antigens is subtype-specific using the van de Vijver dataset (Table 1) (34). The correlation of CT antigen expression with the different breast cancer subtypes in the van de Vijver data were tested with ANOVA analysis. A significant correlation of CT-X expression with the basal subgroup was confirmed for MAGEA4 (P value <0.001), MAGEA10 (P value 0.022), MAGEA5 (P value 0.013), MAGEA2B (P value <0.001), MAGEA5 (P value 0.013), MAGEA6 (P value <0.01), MAGEA12 (P value 0.046), CTAG2 (P value <0.001), MAGEA1 (P value <0.011), and NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B (P value <0.001). Such tumors are of a higher grade and predominantly ER-negative (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

CT-X antigen expression in breast tumor subtypes. The Van de Vivjer dataset (34) was used to determine distribution of CT-X antigen expression. The color bar at the bottom indicates the 5 subtypes defined by Sorlie et al. (33), whereby red indicates basal-like, purple HER2, luminal A blue and B orange, and green the normal like subtype. In the expression matrix, red indicates increased and blue decreased CT-X antigen expression. The upper color bars show biological and clinical aspects of the tumors. Blue and yellow represent a positive and negative status for ER, whereas gold, light green, and dark green represent grades 1, 2, and 3.

Immunohistochemical Demonstration of CT Antigens in Tissue Arrays of Breast Cancer.

To confirm CT-X antigen expression in breast cancer at the tissue level, 3 TMA-based immunohistochemical (IHC) studies were carried out to complement the gene expression studies. The second and third studies built on the results obtained from the first. The salient features are summarized in Tables 4–7, and detailed results are shown in Dataset S1. In a first analysis, a series of 153 unselected cases of infiltrating breast carcinomas were examined revealing 12/153 (8%) tumors positive for MAGEA, and/or NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B or both (Fig. 4, Tables 4–7). CT-X antigen expression was taken as positive when at least 1–2% of the tumor cell population was positively stained. Heterogeneity was a feature for both CT-X antigens. Whereas 103 of the 153 tumors in the series were ER-positive, all but one of the CT-X antigen positive tumors (11/12) fell into the ER/PR-negative category. It was notable that p53 expression was more prominent in the CT-X group (Fig. 4, Tables 4–7) and that most had a high proliferative index as assessed by Ki-67 staining (Dataset S1). The second series comprised a highly selected group of 19 triple negative breast tumors (ER, PR, and HER2-negative). Antigens of the MAGEA or NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B family were present in 9/19 (47%) of these breast tumors (Tables 4–7). Thirteen of these 19 cases were of the basal type, of which 5 were positive for CT-X antigens (Tables 4–7). The final IHC series consisted of 29 matched pairs of primary breast tumors and 53 corresponding brain metastases. These breast tumors had spread preferentially and/or initially to the brain, a feature not infrequently associated with the basal subtype (35). Fourteen of 29 (48%) of these primary tumors showed MAGEA and/or NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B expression (Tables 4–7). Of these 14 CT-X antigen positive tumors, 9 were ER-negative, 7 of which were also PR- negative (Tables 4–7). Thirty-five of 53 (66%) breast cancer metastases to the brain showed the presence of MAGEA and/or NY-ESO/CTAG1B at the protein level. MAGEA and NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B expression individually and combined, was observed in 29, 2, and 4 deposits, respectively. Twenty-one of these CT-X positive metastases were ER-negative, of which 12 were also PR-negative (Tables 4–7).

Table 4.

Immunohistochemistry expression of CT antigens in breast cancer

| Series | Tumor Description | n | No. of tumors with expression |

No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAGEA | NY-ESO-1 | MAGEA/ NY-ESO-1 | MAGEA/ NY-ESO-1 | |||

| 1 | Primary | 153 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 12 (8) |

| 2 | Primary | 19 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 9 (47) |

| 3a | Primary | 29 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 14 (45) |

| 3b | Brain mets from 3a | 53 | 29 | 2 | 4 | 35 (66) |

Table 5.

Characteristics of tumors positive for MAGEA or NY-ESO-1 antigens by immunohistochemistry

| Series | Tumor description | Tumor characteristics |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAGEA or NY-ESO-1 positive | ER neg | P53 pos | Basal | ER neg Basal | ||

| 1 | Primary | 12 | 11 | 10 | ND | ND |

| 2 | Primary | 9 | 9* | ND | 5 | 5 |

| 3a | Primary | 14 | 9† | 9 | 10 | 7 |

| 3b | Brain mets from 3a | 35 | 21‡ | 16 | 25 | 12 |

ND, not done.

*Also PR-negative.

†7/9 also PR-negative.

‡12/21 also PR-negative.

Table 6.

Characteristics of tumors included in the immunohistochemistry series

| Series | Tumor description | n | Tumor characteristics |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER neg | P53 pos | HER2 neg | Basal | EGFR pos | |||

| 1 | Primary | 153 | 50 | 66 | ND | ND | ND |

| 2 | Primary | 19 | 19 | ND | 19 | 13 | 16 |

| 3a | Primary (initial mets to brain) | 29 | 16 | 17 | 12 | 19 | 1 |

| 3b | Brain mets from 3a | 53 | 30 | 23 | 42 | 34 | 4 |

ND, not done.

Table 7.

Overall distribution of MAGEA and NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B positive tumors by ER status

| Tumor description | CT-X positivity | No. |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| MAGEA | NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B | ||

| Primaries | ER-negative | 23 | 3 |

| Primaries | ER-positive | 5 | 0 |

| Metastases | ER-negative | 19 | 2 |

| Metastases | ER-positive | 11 | 0 |

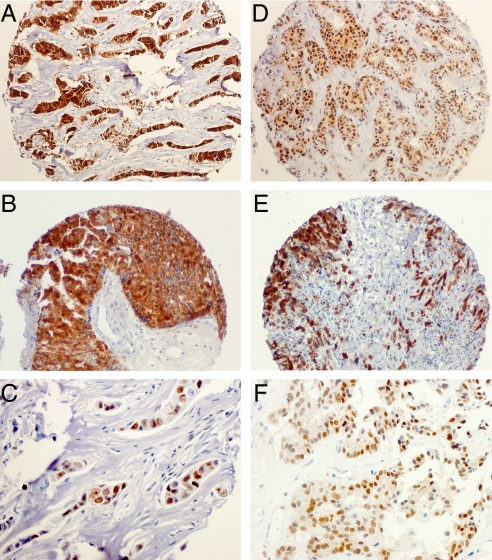

Fig. 4.

Expression of MAGEA, NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B and p53 in primary and metastatic breast tumors. Shown is IHC staining demonstrating the protein expression of MAGEA, NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B, and p53 in primary (A, 10×; B, 20×; C, 100×) and breast cancer metastases to the brain (D, 10×; E, 20×; F, 100×), NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B revealing a mostly cytoplasmic presence of CT-X antigens and the typical nuclear expression of p53.

The overall distribution of ER-positive and ER-negative tumors positive for MAGEA and NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B is shown in Table 7. The data confirm the relative frequency of expression and distribution by ER status found by transcriptional analysis, with NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B being expressed more particularly in ER-negative tumors.

Discussion

The present study suggests that CT-X antigen expression is frequent in ER-negative breast cancer. The single result in the original MPSS data where CT-X antigens were found in an ER-negative breast cell line, and not generally in breast cancer samples or in normal breast tissue, stimulated the subsequent more detailed analysis aimed at determining whether the relationship between ER status and CT-X expression was of broad significance in breast cancer. The ability to access published microarray datasets and carry out a series of defined analyses proved to be invaluable. The analyses of 51 breast cell lines and the 1,259 breast tumors highlighted the association of steroid receptor negative breast cancer and a propensity to express CT-X antigens. The previous assumption of a general low expression of CT antigens in breast cancer is a result of studying unselected series in which ER-negative tumors usually comprise only ≈25% of cases. Indeed, the very first immunopathology study of this work exemplifies this conclusion where less than one-third of the tumors were ER-negative. As a result, only 8% (12/153) of the lesions were CT-X positive, but 11 of the cancers with CT-X expression lacked estrogen receptors (series 1, Tables 4–7).

On the basis of molecular profiling, Perou and Sorlie and their colleagues have classified breast cancer into 5 groups, namely luminal A, luminal B, basal-like, HER2 positive, and so-called normal breast-like (27, 28). Neve et al. (27) have delineated some of the breast cell lines used in the present study (Fig. 1) as being basal-like due to their expression of cytoplasmic components typically found in the basal cells of the normal breast. In our various analyses of the gene arrays, basal-like cell lines and tumors both exhibited higher expression of CT-X antigens. Breast cancers with basal–like features are a recently recognized entity of increasing importance. These lesions are generally of higher grade, have a lower propensity to metastasize to local lymph nodes, exhibit a distinct tendency to spread to brain, and carry a very poor prognosis (35–37). Usually they are ER/PR-negative and do not overexpress HER2. Therefore, these tumors constitute a subset of the so-called triple negative breast cancers.

Consequently, we addressed the question of a potential association of CT-X expression with hormone receptor and/or HER2 status by an immunohistochemical analysis of 2 more collections of breast tumors (series 2 and 3) comprising a high number of ER-negative breast cancers, many of which resembled the basal-like type. We clearly show that MAGEA and NY-ESO/CTAG1B are frequently expressed in such tumors (Tables 4–7).

Current clinical management of breast cancer (early detection, surgery, and cytotoxic drug regimens often in the adjuvant setting) has resulted in significant gains in disease-free and overall survival in recent times (38). Some additional advances have been achieved through the use of targeted forms of therapy such as Tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors for those breast cancers possessing estrogen receptors (39, 40). Trastuzumab (Herceptin), a humanized monoclonal antibody against the extracellular domain of HER2, has been shown recently to benefit patients with HER2-positive primary and metastatic disease (41, 42). Vaccine studies with HER2 peptide in breast cancers expressing ERBB2 are also in progress (43). There remains a need to develop further tumor-specific targets, particularly for those tumors that lack steroid receptors and do not have amplification of HER2.

To date, immunotherapeutic regimens for breast cancer have also been used mainly in end-stage disease and have generally used antigens expressed in normal tissues with elevated expression or expression of mutated forms in tumor cells. Included in this category are antigens such as MUC1, CEA, and the carbohydrate antigens (39). By contrast, current thinking places the role of immunotherapy as being most likely to be effective when patients only have minimal residual disease after initial treatment. CT-X antigens through their restricted distribution in the testis and cancer cells offer a more specific opportunity for vaccine development and therapy. Currently, vaccines comprising members of the MAGEA and NY-ESO-1 families are in clinical trials in patients with melanoma and lung cancer, where such antigens are frequently expressed (11–18).

The present results, therefore, highlight a group of CT-X antigen-expressing steroid receptor-negative breast cancers for which therapeutic options are limited. From the data of this series, it would seem that there is a restricted expression of members of the MAGEA family as well as NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B in almost half of all ER-negative breast cancers, including triple negative and basal-like cancers. In conclusion, our study suggests that a high percentage of ER-negative breast cancer patients may benefit from CT-X antigen-based vaccine treatment.

Materials and Methods

Datasets, Gene Annotations, and Expression Analyses.

The CT antigen database (www.cta.lncc.br/) (2) was used as a reference to extract data corresponding to the CT-X-encoding genes from the 9 microarray datasets analyzed in this study using mRNA accession numbers as cross-references (27–31, 34, 44–47). When several probe sets were available for the same gene, all were used for analysis. Each dataset was subjected to a standard normalization procedure. Values <0.01 were set to 0.01. Each measurement was divided by the 50th percentile of all measurements in that sample. Each probe set was divided by the median of its measurements in all samples. A statistical analysis (ANOVA) was used to identify probe sets with class-specific expression patterns using unfiltered data (22,283 probe sets). For determining the ER-specific expression (ERSE) set, the statistical analysis used the Student 2-sample t test, a P value cut-off of 0.05, and the Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate (48) to control for multiple testing error. A 2-fold change filter was then applied, and probe sets that met these conditions in at least 5 of the 9 datasets investigated were retained. The probability of probe sets meeting these criteria by chance can be estimated using binomial distribution to be ≈P < 3.32 × 10−5. This analysis was repeated separately for the CT-X antigen-encoding genes (66 probe sets).

CT-X Antigen Expression in Molecular Subtypes of Breast Cancers.

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to examine the correlation between the CT-X antigen expression level and the 5 breast tumor subtypes of the van de Vijver dataset as categorized in their original study (34). The P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the method of Benjamini and Hochberg, whereby P values ≤0.05 were considered significant.

Immunohistochemistry of CT-X Antigens and Tissue Microarray Analysis.

Routinely fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks containing mammary carcinomas excised at the time of surgery were extracted from the files of the Department of Surgical Pathology, Weill-Cornell Medical College (IHC series 1), from the files of the Department of Pathology, Austin Hospital, Melbourne (IHC series 2), or from the files of the Department of Pathology, University of Brisbane, Medical Faculty of Charles University in Plzen-Czech Republic, Instituto Nacional do Cancer-Brazil, and Laboratorio Salomao Zoppi-Brazil (IHC series 3). Series 1 and 3 served as donor blocks for the TMAs. The TMAs and series 2 samples were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated through alcohols. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwave boiling in 100 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 15 min or for series 2 and 3 in EDTA (pH 8.0) buffer for 2 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min. Sections were then incubated with affinity purified NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B-specific rabbit polyclonal antibody (NY45) (series 1) or monoclonal antibodies ES121 or E978 specific to NY-ESO-1/CTAG1B (series 2 and 3) and monoclonal antibody specific to MAGEA (detecting multiple MAGE-A antigens, including MAGE-A1, -A3, -A4, and -A6) (6C1, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted in Tris-buffered saline with 10% BSA at 1:1,000 for 1 h at room temperature. The slides were then processed using Dako Envision+ HRP (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark), following the manufacturer's protocol, counterstained briefly with Mayer's hematoxylin (Amber Scientific, Belmont, WA), and cover slipped. Specimens of known antigen-positive tumors were used as a positive control, and negative controls were prepared by omission of the primary antibody or by using a relevant subclass negative control. The various antibodies and their source used to demonstrate breast cancer features are shown in Table S13.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was conducted as part of the Hilton–Ludwig Cancer Metastasis Initiative, funded by the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation and the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research Ltd.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0906840106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Simpson AJ, Caballero OL, Jungbluth A, Chen YT, Old LJ. Cancer/testis antigens, gametogenesis and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:615–625. doi: 10.1038/nrc1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almeida LG, et al. CTdatabase: A knowledge-base of high-throughput and curated data on cancer-testis antigens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;37:D816–D819. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofmann O, et al. Genome-wide analysis of cancer/testis gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20422–20427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810777105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scanlan MJ, Simpson AJ, Old LJ. The cancer/testis genes: Review, standardization, and commentary. Cancer Immun. 2004;4:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gure AO, et al. Cancer-testis genes are coordinately expressed and are markers of poor outcome in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8055–8062. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Velazquez EF, et al. Expression of the cancer/testis antigen NY-ESO-1 in primary and metastatic malignant melanoma (MM)–correlation with prognostic factors. Cancer Immun. 2007;7:11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrade VC, et al. Prognostic impact of cancer/testis antigen expression in advanced stage multiple myeloma patients. Cancer Immun. 2008;8:2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Napoletano C, et al. MAGE-A and NY-ESO-1 expression in cervical cancer: Prognostic factors and effects of chemotherapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:99:e91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scanlan MJ, Gure AO, Jungbluth AA, Old LJ, Chen YT. Cancer/testis antigens: An expanding family of targets for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 2002;188:22–32. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bender A, et al. LUD 00–009: Phase 1 study of intensive course immunization with NY-ESO-1 peptides in HLA-A2 positive patients with NY-ESO-1-expressing cancer. Cancer Immun. 2007;7:16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atanackovic D, et al. Booster vaccination of cancer patients with MAGE-A3 protein reveals long-term immunological memory or tolerance depending on priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1650–1655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707140104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jager E, et al. Recombinant vaccinia/fowlpox NY-ESO-1 vaccines induce both humoral and cellular NY-ESO-1-specific immune responses in cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14453–14458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606512103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Baren N, et al. Tumoral and immunologic response after vaccination of melanoma patients with an ALVAC virus encoding MAGE antigens recognized by T cells. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9008–9021. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valmori D, et al. Vaccination with NY-ESO-1 protein and CpG in Montanide induces integrated antibody/Th1 responses and CD8 T cells through cross-priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8947–8952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703395104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odunsi K, et al. Vaccination with an NY-ESO-1 peptide of HLA class I/II specificities induces integrated humoral and T cell responses in ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12837–12842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703342104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis ID, et al. Recombinant NY-ESO-1 protein with ISCOMATRIX adjuvant induces broad integrated antibody and CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cell responses in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10697–10702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403572101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Theurillat JP, et al. NY-ESO-1 protein expression in primary breast carcinoma and metastases: Correlation with CD8+ T-cell and CD79a+ plasmacytic/B-cell infiltration. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:2411–2417. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandic D, et al. Expression and possible prognostic role of MAGE-A4, NY-ESO-1, and HER-2 antigens in women with relapsing invasive ductal breast cancer: Retrospective immunohistochemical study. Croat Med J. 2006;47:32–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mischo A, et al. Prospective study on the expression of cancer testis genes and antibody responses in 100 consecutive patients with primary breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:696–703. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugita Y, et al. NY-ESO-1 expression and immunogenicity in malignant and benign breast tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2199–2204. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor M, Bolton LM, Johnson P, Elliott T, Murray N. Breast cancer is a promising target for vaccination using cancer-testis antigens known to elicit immune responses. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R46. doi: 10.1186/bcr1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grigoriadis A, et al. Establishment of the epithelial-specific transcriptome of normal and malignant human breast cells based on MPSS and array expression data. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:R56. doi: 10.1186/bcr1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jongeneel CV, et al. An atlas of human gene expression from massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) Genome Res. 2005;15:1007–1014. doi: 10.1101/gr.4041005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin CY, et al. Discovery of estrogen receptor alpha target genes and response elements in breast tumor cells. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R66. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-9-r66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voduc D, Cheang M, Nielsen T. GATA-3 expression in breast cancer has a strong association with estrogen receptor but lacks independent prognostic value. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:365–373. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith DD, et al. Meta-analysis of breast cancer microarray studies in conjunction with conserved cis-elements suggest patterns for coordinate regulation. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neve RM, et al. A collection of breast cancer cell lines for the study of functionally distinct cancer subtypes. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:515–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boersma BJ, et al. A stromal gene signature associated with inflammatory breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1324–1332. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hess KR, et al. Pharmacogenomic predictor of sensitivity to preoperative chemotherapy with paclitaxel and fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4236–4244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doane AS, et al. An estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer subset characterized by a hormonally regulated transcriptional program and response to androgen. Oncogene. 2006;25:3994–4008. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minn AJ, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–524. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perou CM, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorlie T, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8418–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van de Vijver MJ, et al. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1999–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fulford LG, et al. Basal-like grade III invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast: Patterns of metastasis and long-term survival. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R4. doi: 10.1186/bcr1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fulford LG, et al. Specific morphological features predictive for the basal phenotype in grade 3 invasive ductal carcinoma of breast. Histopathology. 2006;49:22–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crabb SJ, et al. Basal breast cancer molecular subtype predicts for lower incidence of axillary lymph node metastases in primary breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2008;8:249–256. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2008.n.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quinn MJ, Cooper N, Rachet B, Mitry E, Coleman MP. Survival from cancer of the breast in women in England and Wales up to 2001. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(Suppl 1):S53–S55. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herold CI, Blackwell KL. Aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer: Proven efficacy across the spectrum of disease. Clin Breast Cancer. 2008;8:50–64. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2008.n.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ponzone R, et al. Antihormones in prevention and treatment of breast cancer. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1089:143–158. doi: 10.1196/annals.1386.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madarnas Y, et al. Adjuvant/neoadjuvant trastuzumab therapy in women with HER-2/neu-overexpressing breast cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:539–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park IH, et al. Trastuzumab treatment beyond brain progression in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:56–62. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benavides LC, et al. The impact of HER2/neu expression level on response to the E75 vaccine: From U.S. Military Cancer Institute Clinical Trials Group Study I-01 and I-02. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2895–2904. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ivshina AV, et al. Genetic reclassification of histologic grade delineates new clinical subtypes of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10292–10301. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, et al. Gene-expression profiles to predict distant metastasis of lymph-node-negative primary breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:671–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Desmedt C, et al. Strong time dependence of the 76-gene prognostic signature for node-negative breast cancer patients in the TRANSBIG multicenter independent validation series. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3207–3214. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sotiriou C, et al. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: Understanding the molecular basis of histologic grade to improve prognosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:262–272. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav Brain Res. 2001;125:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.