Abstract

Background

This study was undertaken to examine the patterns of use for adjuvant therapy and the change in surgical practice for patients with early-stage breast cancer, and to describe how recent large clinical trial results impacted the patterns of care at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC).

Methods

The study included 5,486 women who were diagnosed with stage I to IIIA breast cancer between 1997 and 2004 and received their treatment at MDACC. A chi-squared trend test and multivariable logistic regression model were used to assess changes in treatment patterns over time.

Results

Among node-positive patients, the use of anthracycline plus taxane chemotherapy increased from 17% in 1997 to 81% in 2004 (P < 0.001). Meanwhile, the use of anthracyclines without taxanes dropped from 76% to 20% (P <0.001) between 1997 and 2000. For postmenopausal patients receiving endocrine therapy, the use of tamoxifen has been increasingly replaced by the use of aromatase inhibitors (from 100% on tamoxifen in 1997 to 14% in 2004 (P < 0.001)). The proportion of women who received initial sentinel lymph-node biopsy increased significantly from 1997 to 2004 (1.8% to 69.7% among patients receiving mastectomy, and 18.1% to 87.1% among patients receiving breast-conserving surgery; P < 0.001).

Conclusion

The results from our study suggest that key findings in adjuvant therapy and surgical procedure from large clinical trials often prompt immediate changes in the patient care practices of research hospitals such as M. D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Keywords: breast cancer, chemotherapy, endocrine/hormone therapy, sentinel lymph-node biopsy

Introduction

Breast cancer treatments have substantially improved over the past two decades, which has led to a reduction in breast cancer morbidity and mortality.1–3 More recent clinical trials of adjuvant therapies have established the benefits of taxanes, trastuzumab, and aromatase inhibitors (AIs) for women with early-stage breast cancer.4–7 In addition, surgical management has changed with the development of the sentinel node procedure.8–10 Although the guidelines for surgical management and use of adjuvant therapy for breast cancer have been updated periodically,11–13 the most recent trial results have often been rapidly disseminated to practicing physicians and clinical communities through conferences and publications.

There have recently been several key findings related to both systemic adjuvant therapies and surgical management in breast cancer oncology. Although there were population-based studies for patterns of breast cancer treatment, most of the studies were based on cancer registry data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) and SEER-Medicare databases and focused on breast cancer patients who were older than 65 years.14–17 The few studies based on National Cancer Institute (NCI) Patterns of Care/Quality of Care (POC/QOC) studies with randomly sampled data from younger patients15–18 restricted cohorts to breast cancers diagnosed in the years 1987 to 1991, 1995, and 2000. Little information is available regarding patterns of care for early-stage breast cancer treatment from 1997 to 2004, when results from many important randomized clinical trials were disseminated. We aim to examine the patterns of use for adjuvant therapy and the changes in surgical practices for patients with early-stage breast cancer diagnosed between 1997 and 2004. We will also describe how recent large clinical trial results have impacted the patterns of care at academic institutions such as The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC).

METHODS

Data Sources

Following approval by the institutional review board of MDACC, we retrieved information on 7146 patients from the Breast Cancer Management System – a prospective electronic database initiated in June of 1997. The patients had been diagnosed with primary breast cancer between June of 1997 and December of 2004 and received treatments at the MDACC Multidisciplinary Breast Cancer Center. For this study, we focused on patients with stage I to IIIA breast cancer by excluding 904 patients with ductal carcinoma and lobular carinoma in situ and 725 patients with stage IIIB, IIIC, or IV tumors. Stage at diagnosis of breast cancer was based on the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) classification.19 We also excluded 37 patients with unknown surgery or stage information. We did not include patients who were treated for recurrent disease only. A patient may have been excluded for more than one reason. A total of 5486 patients were included in the final analysis. The data were abstracted from medical charts, reviewed and updated annually, and entered into the Breast Cancer Management System, which maintains active follow-up of all cases. The variables extracted from the database include patient age, tumor stage, tumor size, nodal status, nuclear grade, estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) status, year of diagnosis, and comorbidities. Clinical stage, lymph node status, and lymph node size were used for patients who received neo-adjuvant therapy; otherwise, pathological staging information was used.

Statistical Analysis

We used the chi-square trend test to assess the changes in treatment patterns over time for chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and surgery. We used multivariable logistic regression models and the estimated odds ratios (ORs) to examine if time was a significant factor in the selection of each primary treatment option while adjusting for tumor characteristics and other demographic factors. The covariates in the multivariable logistic analyses included age at diagnosis, tumor characteristics (tumor size, stage, nodal status, nuclear grade, lymphatics/vascular invasion, ER/PR status), and co-morbid conditions (diabetes, hypertension, heart disease). A backward stepwise regression approach was used to select the final multivariable model, with a P value of less than 0.05 as the limit for inclusion. We calculated the relative risk (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the primary variables of interest. All statistical tests (P values) were two-sided. We performed the statistical analyses using SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) and SPLUS 7.0 (Insightful Corporation, Seattle, Washington).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients by year of diagnosis. There were no substantial changes in tumor stage, tumor size, or ER/PR status over the observation period. The proportion of patients with unknown ER or PR status decreased from 9.3% in 1997 to 1.4% in 2004 (P<0.001). A similar decrease (from 5.8% to 1.1% (P=.006)) was observed for unknown nuclear grade. The proportion of patients with hypertension or heart disease at diagnosis increased from 19.9% to 33.4% and 6.1% to 14.6%, respectively, over the same time period (all P values < 0.001).

Table 1.

Patient Demographic and Tumor Characteristics by Year of Diagnosis

| 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | P value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=396) | (N=624) | (N=699) | (N=703) | (N=755) | (N=816) | (N=754) | (N=739) | ||

| Characteristics | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Age | |||||||||

| < 65 | 81.1 | 78.2 | 82.0 | 80.4 | 77.9 | 79.4 | 79.8 | 77.8 | |

| >=65 | 18.9 | 21.8 | 18.0 | 19.6 | 22.1 | 20.6 | 20.2 | 22.2 | 0.250 |

| Tumor Stage | |||||||||

| I | 41.2 | 42.3 | 44.6 | 44.7 | 45.4 | 42.3 | 45.9 | 40.7 | |

| II/III | 58.8 | 57.7 | 55.4 | 55.3 | 54.6 | 57.7 | 54.1 | 59.3 | 0.997 |

| Tumor Size | |||||||||

| T0/T1 | 59.3 | 59.8 | 61.9 | 61.6 | 62.1 | 59.4 | 61.1 | 56.6 | |

| T2/T3 | 39.7 | 39.9 | 37.8 | 38.4 | 37.8 | 40.2 | 38.6 | 43.0 | 0.257 |

| Unknown | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.442 |

| Nodal Status | |||||||||

| Negative | 59.3 | 59.0 | 62.5 | 61.6 | 63.4 | 60.8 | 66.4 | 64.7 | |

| Positive | 40.7 | 41.0 | 37.5 | 38.4 | 36.6 | 39.2 | 33.6 | 35.3 | 0.006 |

| Nuclear Grade | |||||||||

| Well/Moderate | 44.4 | 46.8 | 49.8 | 50.6 | 55.0 | 51.6 | 51.2 | 54.0 | |

| Poorly | 49.7 | 49.5 | 47.9 | 47.9 | 43.4 | 46.6 | 46.7 | 44.9 | 0.006 |

| Unknown | 5.8 | 3.7 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 0.006 |

| ER/PR Status | |||||||||

| ER and PR Negative | 19.7 | 15.5 | 24.0 | 21.1 | 19.2 | 22.4 | 21.0 | 21.8 | |

| ER or PR Positive | 71.0 | 75.3 | 70.1 | 75.2 | 76.8 | 72.5 | 77.3 | 76.9 | 0.492 |

| Unknown | 9.3 | 9.1 | 5.9 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 1.7 | 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | |||||||||

| No | 93.9 | 93.4 | 93.0 | 94.2 | 92.7 | 91.2 | 91.0 | 91.9 | |

| Yes | 6.1 | 6.6 | 7.0 | 5.8 | 7.3 | 8.8 | 9.0 | 8.1 | 0.012 |

| Hypertension | |||||||||

| No | 80.1 | 73.9 | 75.5 | 70.1 | 66.5 | 69.5 | 67.6 | 66.6 | |

| Yes | 19.9 | 26.1 | 24.5 | 29.9 | 33.5 | 30.5 | 32.4 | 33.4 | < 0.001 |

| Heart Disease | |||||||||

| No | 93.9 | 94.4 | 92.4 | 90.3 | 87.4 | 87.3 | 88.2 | 85.4 | |

| Yes | 6.1 | 5.6 | 7.6 | 9.7 | 12.6 | 12.7 | 11.8 | 14.6 | < 0.001 |

P values are based on Cochran-Armitage trend test.

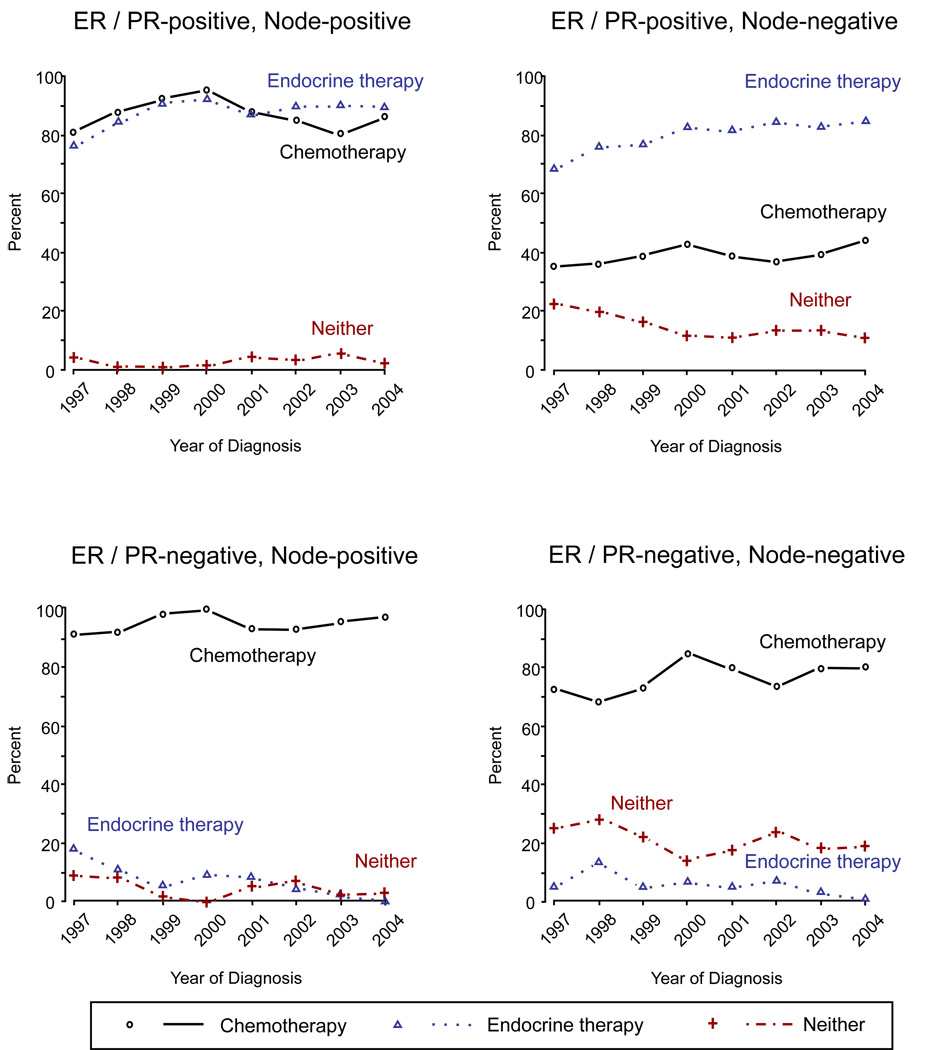

Use of chemotherapy and endocrine therapy

Figure 1 shows the use of chemotherapy and endocrine therapy over time, examined by ER/PR status and node status. The proportion of patients with ER or PR positive tumors treated with endocrine therapy increased from 76% to 89% for node-positive patients (P = 0.004) and from 68% to 84% for node-negative patients (P < 0.001) from 1997 to 2004. For patients with both ER and PR negative tumors, the use of endocrine therapy decreased substantially: from 18% to 0% (P = 0.003) for node-positive patients and from 5% to 1% (P = 0.009) for node-negative patients. The use of chemotherapy had a modest but not statistically significant increase for all subgroup patients from 1997 to 2004. During the same time period, the percentage of use of neither adjuvant therapy dropped: from 23% in 1997 to 11% in 2004 (P < 0.001) among ER or PR positive and node-negative patients.

Figure 1.

Use of Chemotherapy and Endocrine Therapy by ER/PR Status and Node Status

Using a logistic regression model (Table 2), we found that the use of chemotherapy increased about 34% from 1997–1999 to 2003–2004 after adjusting for age at diagnosis, tumor size, nodal status, ER/PR status, nuclear grade, and co-morbid conditions (diabetes and heart disease). As expected, the use of chemotherapy was higher for younger women and women with larger tumors, positive nodes, fewer co-morbid conditions, and ER and PR negative tumors.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for Chemotherapy vs Without Chemotherapy (n = 5130)

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI*) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Year of Diagnosis | ||

| 97 –99 | 1.00 | |

| 00 – 02 | 1.46 (1.21 – 1.76) | <0.001 |

| 03 – 04 | 1.34 (1.09 – 1.64) | 0.005 |

| Age | ||

| (every 10 years increase) | 0.44 (0.41 – 0.47) | <0.001 |

| Tumor Size | ||

| T0/T1 | 1.00 | |

| T2 | 6.67 (5.51 – 8.08) | <0.001 |

| T3 | 18.17(9.81 – 33.68) | <0.001 |

| Nodal Status | ||

| Negative | 1.00 | |

| Positive | 9.80 (8.10 – 11.86) | <0.001 |

| Nuclear Grade | ||

| Well/Moderate | 1.00 | |

| Poorly | 2.12 (1.78 – 2.52) | <0.001 |

| ER/PR Status | ||

| Negative | 1.00 | |

| Positive | 0.37 (0.30 – 0.47) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 0.72 (0.53 – 0.96) | 0.028 |

| Heart Disease | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 0.75 (0.58 – 0.97) | 0.029 |

CI, confidence interval

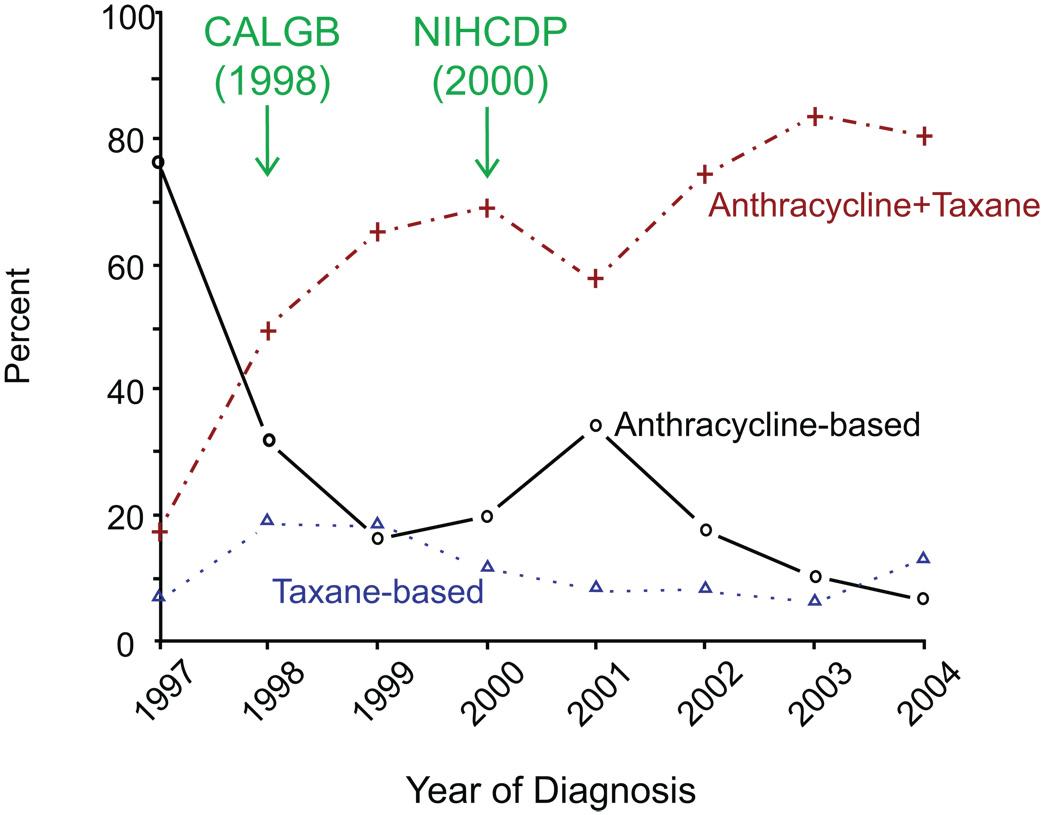

Type of chemotherapy: anthracycline, taxane, and anthracycline + taxane

As shown in Figure 2, among early-stage patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy, the use of a combination of anthracycline-based and taxane chemotherapy increased from 17% to 81% for node-positive patients (P < 0.001). Meanwhile, the use of anthracyclines without taxanes among node-positive patients dramatically dropped from 76% to 20% (P < 0.001) between 1997 and 2000 (Figure 2). For node-positive patients, the use of chemotherapy with anthracycline plus taxane had a significant jump, starting in 1998, when the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALBG) Study 9344 results were presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting. The use of anthracyclines plus taxanes decreased after the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Conference (NIHCDP) on adjuvant therapy of breast cancer in 2001, but then increased and stabilized at around 80% for node-positive patients.

Figure 2.

Type of Chemotherapy among Node-positive Women

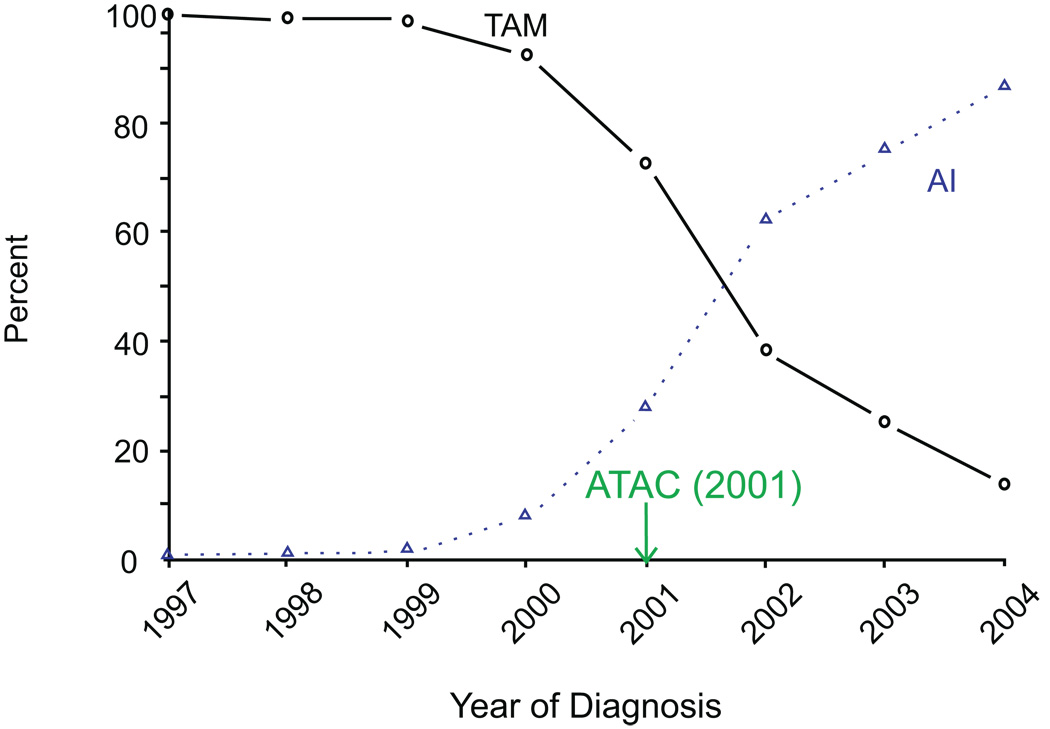

Type of endocrine therapy: AIs vs tamoxifen

For postmenopausal patients receiving endocrine therapy, the use of tamoxifen (TAM) has been increasingly replaced by the use of AIs, from 100% on TAM in 1997 to 14% in 2004 (P < 0.001) (Figure 3). The multivariable logistic regression model shows a dramatic increase in AI usage during 2003–2004 compared to 1997–2002 for women postmenopausal at diagnosis (OR=16.17, 95% CI: 12.79, 20.43) (Table 3). The switch to AIs for post-menopausal women started in 2000, right around the presentation of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) study results that showed anastrozole (one of the AIs) was superior to TAM in both efficacy and side effect profile for postmenopausal women.

Figure 3.

Type of Endocrine Therapy among Post-menopausal Women

Table 3.

Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for Use of Aromatase Inhibitors vs Tamoxifen among Post-menopause Women (n = 2253)

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI*) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Year of Diagnosis | ||

| 97 –02 | 1.00 | |

| 03 – 04 | 16.17 (12.79 – 20.43) | <0.001 |

| Nodal Status | ||

| Negative | 1.00 | |

| Positive | 1.50 (1.22 – 1.86) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 1.41 (1.14 – 1.74) | 0.001 |

| Heart Disease | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 1.63 (1.21 – 2.20) | 0.001 |

CI, confidence interval.

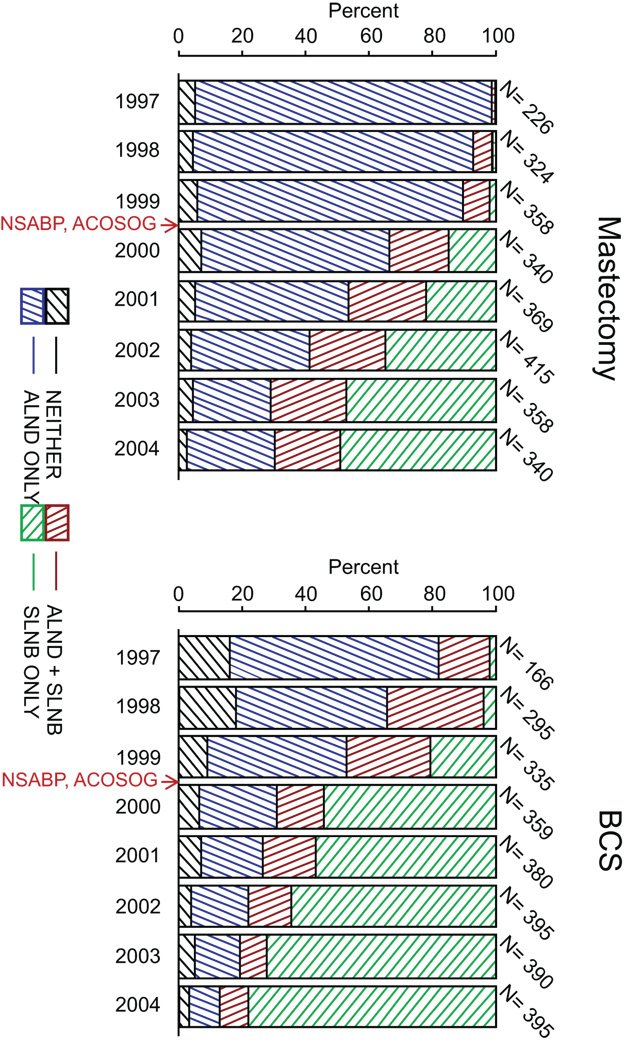

Surgery

In the study cohort including both clinical negative and positive node assessment, the proportion of women who received initial sentinel lymph-node biopsies (SLNBs) increased significantly among patients receiving mastectomy, from 1.8% in 1997 to 69.7% in 2004 (P < 0.001); among patients receiving breast-conserving surgery (BCS), the proportion increased from 18.1% in 1997 to 87.1% in 2004 (P < 0.001) (Figure 4). The proportion of women receiving axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) without initial SLNB significantly decreased (from 93.4% to 27.6% among mastectomy patients and from 65.7% to 9.9% among BCS patients) between 1997 and 2004. The use of neither SLNB nor ALND remained around 3–11% during the same time period. A multivariable analysis was performed to assess the change in the use of SLNB over three time periods (OR=21.9, 95% CI: 17.7, 27.2 for 2003–2004 versus 1997–1999; OR=8.4, 95% CI: 7.1, 10.0 for 2000–2002 versus 1997–1999) after adjusting for clinical tumor size, clinical node status, and surgery type (Table 4). As expected, patients with larger tumor sizes were less likely to receive SLNBs than those with smaller tumors; patients receiving mastectomies were less likely to receive SLNBs than those receiving BCS. An alternative analysis was performed, and included patients who did not have information on clinical tumor size or nodal status but had information on pathologic tumor size and nodal status. There was no noticeable change in the parameter estimates in the multivariable model. The largest increase of SLNBs with or without subsequent ALND occurred in 2000, between the initiation of two large randomized surgical trials to assess the use of SLNB: the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011 trial (initiated in 1999), and the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) Protocol B-32 trial (opened to accrual in 2001).

Figure 4.

Percentage of Patients who Received SLNB and/or ALND by Year of Diagnosis, according to Type of Surgery

Table 4.

Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for SLNB vs Without SLNB (n = 4892)

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI*) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Year of Diagnosis | ||

| 97 –99 | 1.00 | |

| 00 – 02 | 8.41 (7.05 – 10.02) | <0.001 |

| 03 – 04 | 21.94 (17.70 – 27.20) | <0.001 |

| Clinical Tumor Size | ||

| T0/T1 | 1.00 | |

| T2 | 0.12 (0.10 -∓ 0.15) | <0.001 |

| T3 | 0.03 (0.01 -∓ 0.07) | <0.001 |

| Clinical Nodal Status | ||

| N0 | 1.00 | |

| N1 | 0.68 (0.58 – 0.79) | <0.001 |

| N2 | 0.44 (0.31 – 0.62) | <0.001 |

| Type of Surgery | ||

| Mastectomy | 1.00 | |

| Breast-conserving Surgery | 3.10 (2.67 – 3.60) | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

Using data from more than 5400 early-stage breast cancer patients who had been treated at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center from June of 1997 to December of 2004, we found several important changes in the use of systemic adjuvant treatments and in surgery practices. Estimation of the dissemination of adjuvant therapy over the study period showed not only changes in the overall usage of adjuvant therapies, but in the types of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy. Our findings have clinical relevance because the rapid changes in practice patterns allow more patients access to state-of-the-art treatment, and should thus improve clinical outcomes.

Among patients receiving chemotherapy, there was a clear increase in the use of anthracycline plus taxane. This was most evident in 1998, when the results from the CALGB study of adjuvant paclitaxel was presented at ASCO and showed a survival benefit of adding 4 cycles of paclitaxel to 4 cycles of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide for lymph node positive breast cancer. The use of anthracycline plus paclitaxel continued to increase from 1998 to 2000. The drop in use during 2001 was likely in reaction to the NIHCDP, at which the NSABP Protocol B28 trial results were presented, which indicated that no survival benefit was seen for adjuvant paclitaxel in combination with anthracycline.20 Subsequently, the NIH did not recommend routine use of paclitaxel. Since then, and with additional studies and longer follow up for the Protocol B28 trial, the benefits of taxanes have been confirmed and established.4, 21–23 Although additional controversy existed regarding the benefit of paclitaxel in ER positive patients, we saw little evidence that the use of taxanes at MDACC was determined by estrogen receptor status.11, 13

Since the late 1980s, TAM has become the standard of care for breast cancer patients with ER positive tumors.24, 25 The role of AIs in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer in postmenopausal women has recently been evaluated by several large clinical trials.11, 26–28 The benefit of the new generation of AIs has prompted a quick shift at MDACC from treating postmenopausal patients with TAM to AIs, with an increase from <1% in 1999 to 86% in 2004. The first big jump corresponded with the presentation of the ATAC study results at the San Antonio Breast Conference in 2001, which showed that AIs were superior to TAM in both efficacy and side effect profile with a median follow-up of 33 months.12, 20, 28–34 MDACC was one of the centers participating in the ATAC trial.

Attention has recently been paid to the undertreatment of older patients.14, 35–39 While the use of any adjuvant therapy for women with ER/PR positive tumors was already high at MDACC in 1997, a further increase was observed in the use of adjuvant therapy for patients with node-negative tumors (from 78% to 90%). This change was particularly evident for patients older than 65 years, for which the proportion of no adjuvant therapy declined from 34% in 1997 to 20% in 2004. Interestingly, for patients older than 65 years there was also a sharp shift from endocrine only adjuvant therapy (41% in 1998 to 16% in 1999) to the combination of chemotherapy and endocrine therapy (37% in 1998 to 65% in 1999). This usage pattern of adjuvant therapies has been consistent with guidelines and the increasing recognition of the benefit of chemotherapy in healthy older women.15, 40–42

We also compared the use of systemic chemotherapy for patients treated at MDACC and for patients treated at community-based practices during the same time period. Using the SEER POC/QOC database15–16, Harlan and her colleagues found that the percentage of women receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy increased significantly between 1995 and 2000.17 To compare with their study, we used a subset of patients diagnosed in 2000 and treated at MDACC and a subset of patients from the SEER/POC database also diagnosed in 2000. For all categories, the percentages of anthracycline-based multiagent chemotherapy use at MDACC were larger than those from the SEER POC/QOC study for the same year. For patients with node-negative tumors at age <50, 50–69, and older than 69, the percentages receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy were 96%, 94%, and 90%, respectively, at MDACC versus 71%, 80%, and 19%, respectively, from the SEER POC/QOC database. For node-positive patients with the same age cohorts, the percentages using anthracyclines were 98%, 95%, and 86%, respectively, at MDACC versus 87%, 81%, and 10%, respectively, from the SEER POC/QOC database. Although the results from the SEER POC/QOC database suggest that physicians in community-based practice adapted to the updated guidelines for breast cancer systemic chemotherapy over the study period, the comparison shows that MDACC has responded more quickly to publications and conference presentations and used more aggressive anthracycline-based multiagent regimens for patients older than 65 years.

A dramatic change from ALND to SLNB in surgery practice has been observed for early-stage breast cancers at MDACC since 1999, while BCS has been considered a standard practice per guideline since the mid-1990s for patients with stage I-II tumors.15, 43–45 Traditionally, axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) had been used to remove all level 1 and level 2 axillary lymph nodes in patients undergoing surgery for breast cancer, which resulted in an increased risk for lymphedema and functional deficits in the ipsilateral upper extremity.46 Beginning in the late 1990s, two large NCI sponsored trials, the NSABP Protocol B-32 and ACOSOG Z-0010 trials, opened to evaluate the use of SLNB as a less invasive alternative to ALND. The NSABP Protocol B-32 trial is still ongoing to assess long-term outcomes. In 2005, an ASCO expert panel reported a systematic review of the literature available through 2004 on the use of SLNB in early-stage breast cancer, including one randomized clinical trial completed in Europe8 and 69 single-institution and multicenter trials.9 Based on its review, the panel issued a treatment guideline for SLNB and concluded it to be a safe and accurate initial method for identifying early-stage breast cancer without involvement of the remainder of the lymph node basin. While SLNB alone results in fewer surgical complications than ALND (as confirmed by the recently completed ACOSOG Z0011 trial and other studies4, 10, 47–51) the comparative effects of these two approaches on long-term recurrence and survival are promising but need to be further confirmed.52, 53 As noted by Edge,54,55 there was widespread use of SLNB outside the clinical trial setting and this procedure was accepted as the standard-of-care (especially among NCI designated comprehensive cancer centers, including MDACC) before the randomized clinical trials started. MDACC was one of the centers that entered women on the randomized NSABP Protocol B-32 and ACOSOG Z0011 trials. It is clear that a pattern of increased use of SLNB at MDACC between 1998 and 2004 is similar to but more substantial than that observed in the national population samples in Chen et al (29% in 1998 to 65% in 2004, compared with 21% in 1998 to 82% in 2004 at MDACC for stage I-II patients who received SLNB).56

There are several limitations to our study. During the study period, 20% of the MDACC patients in our study sample were treated within clinical trials. As one of NCI-designated cancer centers, MDACC has directly involved and enrolled patients for many of the large multicenter clinical trials that assess new adjuvant therapies or surgical procedures (e.g., ATAC, NSABP, ACOSO Z0011 trial, and others). The observed pattern of change in treating early-stage breast cancer at a typical academic cancer center may not be generalized to the community-based clinical practice. This limitation is balanced by the advantages of using the database at MDACC with detailed treatment information, demographic variables, tumor characteristics, and comorbidity condition at the individual level. Most literature regarding patterns of breast cancer treatment based on SEER databases had to focus on patients older than 65 years through SEER-Medicare,14, 39, 43, 44, 57, because reliable treatment data for patients younger than 65 years were unavailable. The few studies based on the SEER (POC/QOC) database15–18 with randomly sampled younger patient data restricted cohorts to early-stage breast cancers diagnosed in the years 1987 to 1991, 1995, and 2000. Our database covers a continuous horizon from 1997 to 2004, a period in which many of the important clinical trials had been conducted and the results had been reported. Finally, like any other study for patterns of care, we do not have detailed information on patient compliance with their endocrine therapy. Unlike chemotherapies, the investigated pattern of endocrine therapy is a prescription pattern, which may not fully reflect the treatments that patients actually received.

The results from our study suggest that key findings in chemotherapy and endocrine therapy from large clinical trials over the last decade often prompted immediate change in patient care practices in research hospitals such as MDACC. To some extent, this may be due to the academic setting, in which the evolvement from ALND to SLNB for early-stage breast cancer in surgery practice at MDACC began when the large randomized clinical trials were initiated and represented patient participating in these trials. The changes in practice at MDACC often occurred earlier than those in national practice patterns, and reflected the academic setting with a multidisciplinary approach to patient care and many educational conferences to keep all faculty abreast of medial advances, and possibly early knowledge about the formal presentation of clinical trial results.

Acknowledgements

We thank Shu-Wan Kau and Limin Hsu for their assistance in data management and data clarification.

Sources of support: Supported by Research Grants Nos. CA-79466 and CA-016672 from the National Cancer Institute, and a grant from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network to fund, in part, the Breast Cancer Medical System database of M. D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: There are no financial disclosures from any authors.

The results suggest that key findings in adjuvant therapy and surgical management from large clinical trials often prompt immediate changes in the patient care practices of research hospitals such as M. D. Anderson Cancer Center.

References

- 1.Berry DA, Inoue L, Shen Y, et al. Modeling the impact of treatment and screening on U.S. breast cancer mortality: a Bayesian approach. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2006;36:30–36. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgj006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101:3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moulder S, Hortobagyi GN. Advances in the treatment of breast cancer. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008 Jan;83:26–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson IC, Berry DA, Demetri GD, et al. Improved outcomes from adding sequential Paclitaxel but not from escalating Doxorubicin dose in an adjuvant chemotherapy regimen for patients with node-positive primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:976–983. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coombes RC, Kilburn LS, Snowdon CF, et al. Survival and safety of exemestane versus tamoxifen after 2–3 years' tamoxifen treatment (Intergroup Exemestane Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:559–570. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, et al. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years' adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:60–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17666-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1673–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, et al. A randomized comparison of sentinel-node biopsy with routine axillary dissection in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:546–553. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyman GH, Giuliano AE, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline recommendations for sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7703–7720. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucci A, McCall LM, Beitsch PD, et al. Surgical complications associated with sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND) plus axillary lymph node dissection compared with SLND alone in the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Trial Z0011. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3657–3663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Panel. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference statement : adjuvant therapy for breast cancer, November 1–3, 2000. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2001;(30):5–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NIH consensus conference. Treatment of early-stage breast cancer. JAMA. 1991;265:391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du X, Goodwin JS. Patterns of use of chemotherapy for breast cancer in older women: findings from Medicare claims data. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1455–1461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards BK, Brown ML, Wingo PA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2002, featuring population-based trends in cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1407–1427. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harlan LC, Abrams J, Warren JL, Clegg L, Stevens J, Ballard-Barbash R. Adjuvant therapy for breast cancer: practice patterns of community physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1809–1817. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harlan LC, Clegg LX, Abrams J, Stevens JL, Ballard-Barbash R. Community-based use of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early-stage breast cancer: 1987–2000. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:872–877. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.5840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mariotto A, Feuer EJ, Harlan LC, Wun LM, Johnson KA, Abrams J. Trends in use of adjuvant multi-agent chemotherapy and tamoxifen for breast cancer in the United States: 1975–1999. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1626–1634. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.21.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singletary SE, Allred C, Ashley P, et al. Revision of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3628–3636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eifel P, Axelson JA, Costa J, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: adjuvant therapy for breast cancer, November 1–3, 2000. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:979–989. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.13.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin M, Pienkowski T, Mackey J, et al. Adjuvant docetaxel for node-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2302–2313. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heys SD, Hutcheon AW, Sarkar TK, et al. Neoadjuvant docetaxel in breast cancer: 3-year survival results from the Aberdeen trial. Clin Breast Cancer. 2002;3(suppl 2):S69–S74. doi: 10.3816/cbc.2002.s.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cristofanilli M, Hortobagyi GN. Breast cancer highlights: key findings from the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium: a U.S. perspective. Oncologist. 2004;9:471–478. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-4-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NCI alert on node-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1988;12:3–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01805734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher B, Dignam J, Wolmark N, et al. Tamoxifen and chemotherapy for lymph node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1673–1682. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.22.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Gelber RD, Coates AS, Thurlimann B, Senn HJ. Meeting highlights: updated international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3357–3365. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.for the International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) Castiglione-Gertsch M, O'Neill A, Price KN, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy followed by goserelin versus either modality alone for premenopausal lymph node-negative breast cancer: a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1833–1846. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crivellari D, Price K, Gelber RD, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy compared with no systemic therapy for elderly women with early breast cancer: 21-year results of International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial IV. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4517–4523. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nabholtz JM, Buzdar A, Pollak M, et al. Anastrozole is superior to tamoxifen as first-line therapy for advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women : results of a North American multicenter randomized trial. Arimidex Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3758–3767. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.22.3758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buzdar AU. New generation aromatase inhibitors--from the advanced to the adjuvant setting. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;75(suppl 1):S13–S17. doi: 10.1023/a:1020305615033. discussion S33-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baum M, Budzar AU, Cuzick J, et al. Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: first results of the ATAC randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2131–2139. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winer EP, Hudis C, Burstein HJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology technology assessment on the use of aromatase inhibitors as adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: status report 2004. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:619–629. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mouridsen H, Gershanovich M, Sun Y, et al. Phase III study of letrozole versus tamoxifen as first-line therapy of advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women: analysis of survival and update of efficacy from the International Letrozole Breast Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2101–2109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.for the Breast International Group (BIG) 1–98 Collaborative Group. Thurlimann B, Keshaviah A, Coates AS, et al. A comparison of letrozole and tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2747–2757. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giordano SH, Hortobagyi GN, Kau SW, Theriault RL, Bondy ML. Breast cancer treatment guidelines in older women. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:783–791. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenfield S, Blanco DM, Elashoff RM, Ganz PA. Patterns of care related to age of breast cancer patients. JAMA. 1987;257:2766–2770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goodwin JS, Hunt WC, Samet JM. Determinants of cancer therapy in elderly patients. Cancer. 1993;72:594–601. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930715)72:2<594::aid-cncr2820720243>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silliman RA, Troyan SL, Guadagnoli E, Kaplan SH, Greenfield S. The impact of age, marital status, and physician-patient interactions on the care of older women with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;80:1326–1334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mandelblatt JS, Hadley J, Kerner JF, et al. Patterns of breast carcinoma treatment in older women: patient preference and clinical and physical influences. Cancer. 2000;89:561–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forbes JF, Gradishar WJ, Ravdin PM. Choosing between endocrine therapy and chemotherapy--or is there a role for combination therapy? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;75(suppl 1):S37–S44. doi: 10.1023/a:1020365800921. discussion S57-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez EA. Management recommendations for adjuvant systemic breast cancer therapy. Breast Dis. 2004;21:15–21. doi: 10.3233/bd-2004-21103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tuma RS. Latest studies hint at survival advantage with aromatase inhibitors in early breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:86–87. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ballard-Barbash R, Potosky AL, Harlan LC, Nayfield SG, Kessler LG. Factors associated with surgical and radiation therapy for early stage breast cancer in older women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:716–726. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.11.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riley GF, Potosky AL, Klabunde CN, Warren JL, Ballard-Barbash R. Stage at diagnosis and treatment patterns among older women with breast cancer: an HMO and fee-for-service comparison. JAMA. 1999;281:720–726. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.8.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark RM, Whelan T, Levine M, et al. Randomized clinical trial of breast irradiation following lumpectomy and axillary dissection for node-negative breast cancer: an update. Ontario Clinical Oncology Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1659–1664. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.22.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulze T, Mucke J, Markwardt J, Schlag PM, Bembenek A. Long-term morbidity of patients with early breast cancer after sentinel lymph node biopsy compared to axillary lymph node dissection. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:109–119. doi: 10.1002/jso.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crivellari D, Aapro M, Leonard R, et al. Breast cancer in the elderly. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1882–1890. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Veronesi U, Boyle P, Goldhirsch A, Orecchia R, Viale G. Breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:1727–1741. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66546-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.for the International Breast Cancer Study Group. Rudenstam CM, Zahrieh D, Forbes JF, et al. Randomized trial comparing axillary clearance versus no axillary clearance in older patients with breast cancer: first results of International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial 10–93. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:337–344. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.5784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mansel RE, Goyal A. Newcombe RG for the ALMANAC Trialists Group. Internal mammary node drainage and its role in sentinel lymph node biopsy: the initial ALMANAC experience. Clin Breast Cancer. 2004;5:279–284. doi: 10.3816/cbc.2004.n.031. discussion 285–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mansel RE, Fallowfield L, Kissin M, et al. Randomized multicenter trial of sentinel node biopsy versus standard axillary treatment in operable breast cancer: the ALMANAC Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:599–609. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blanchard DK, Donohue JH, Reynolds C, Grant CS. Relapse and morbidity in patients undergoing sentinel lymph node biopsy alone or with axillary dissection for breast cancer. Arch Surg. 2003;138:482–487. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.5.482. discussion 487–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Badgwell BD, Povoski SP, Abdessalam SF, et al. Patterns of recurrence after sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:376–380. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Edge SB. Early adoption and disturbing disparities in sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:449–450. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edge SB, Niland JC, Bookman MA, et al. Emergence of sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer as standard-of-care in academic comprehensive cancer centers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1514–1521. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen AY, Halpern MT, Schrag NM, Stewart A, Leitch M, Ward E. Disparities and trends in sentinel lymph node biopsy among early-stage breast cancer patients (1998–2005) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:462–474. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Giordano SH, Duan Z, Kuo YF, Hortobagyi GN, Goodwin JS. Use and outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2750–2756. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]