Abstract

Attrition from treatment for substance abuse disorders (SUD) is a persistent challenge that severely limits the effectiveness of services. Though a large body of research has sought to identify predictors of retention, the perspective of clients of services is rarely examined. This exploratory qualitative study presents clients’ stated reasons for leaving outpatient treatment (N = 135, 54% of the sample of 250) and their views of what could have been done differently to keep them engaged in services. Obstacles to retention fell into program- and individual-level factors; the former includes dissatisfaction with the program, especially counselors, unmet social services needs, and lack of flexibility in scheduling; individual-level barriers to retention were low problem recognition and substance use. Study limitations are noted and the implications of findings for research and practice are discussed, emphasizing the need to understand and address clients’ needs and expectations starting at intake to maximize treatment retention and the likelihood of positive outcomes.

Keywords: Substance abuse services, treatment, recovery, addiction, chronic care model, qualitative methods

1. Introduction

1.1 Treatment retention and completion foster positive outcomes

Addiction is, for many, a chronic condition (McLellan, Lewis, O'Brien, & Kleber, 2000) that has persisted and increased in severity for many years, sometimes decades before help is sought (Dennis, Scott, Funk, & Foss, 2005). Acquiring the skills and resources necessary to initiate and maintain the cognitive and behavioral changes required to address addiction takes time. The goals of treatment include strengthening personal resources (e.g., self-confidence, coping skills), helping clients acquire ‘alternative rewards’ – valued assets that will ‘increase the price of return to substance use (e.g., health-related and economic well-being and overall improved life satisfaction (Laudet, Becker, & White, 2009), connecting them to protective activities (e.g., 12-step fellowships), and strengthening supportive relationships with family and friends (Moos & Moos, 2007). It has been argued that one of the main functions of the addiction treatment counselor is to keep patients engaged in treatment so that they can develop adaptive skills and relationships (Simpson, Joe, Broome, Hiller, & Knight, 1997).

Longer participation in treatment is associated with stabilization and/or improvement in protective resources that, in turn, bolster the long-term effects of treatment and mediate part of its influence on remission from substance use up to 15 years later. The effect of treatment on protective resources ‘may contribute more to long-term remission than does treatment oriented toward reducing or eliminating substance use per se” (Moos & Moos, 2007, p.52). Greater treatment duration is associated with better substance use outcomes across treatment modalities (Council, 2004; Finney & Moos, 1998; Hawkins et al., 2007; Hubbard et al., 2003; McKay & Weiss, 2001; McLellan et al., 1996; Simpson et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2003) and increased treatment retention is one of the key outcome domains collected for SAMHSA's National Outcome Measures (NOMs - Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008). Treatment completion, which is typically associated with longer retention (SAMHSA Treatment Episode Data Set 2004, 2006) is consistently linked to improved long-term outcomes in terms of substance use but also of employment and criminal involvement (Grella, Joshi, & Hser, 2000; Hubbard et al., 2003; Stark, 1992; Wallace & Weeks, 2004).

Regrettably, treatment completion and retention are well-documented problems in the addiction services field (Carroll, 1997; Mattson et al., 1998; Stark, 1992). The completion rate for publicly funded programs in 2005 was 44% across modalities, 36% in outpatient settings, the most common form of service delivery in the US (SAMHSA Treatment Episode Data Set 2005, 2008).

1.2 Factors associated with treatment retention

Given the challenges of keeping clients engaged in treatment, strategies to improve retention can provide services with a powerful tool to affect health and psychosocial outcomes (Hellemann, Conner, Anglin, & Longshore, 2009) and thus represent important opportunities to enhance the effectiveness of substance abuse treatment (Hawkins et al., 2007; Kelly & Moos, 2003; Siqueland et al., 1998). A large body of research has sought to identify predictors of retention. Most studies focus on fixed pre-admission client characteristics (e.g., demographics, clinical domains - Magura, Nwakeze, & Demsky, 1998; Marsch et al., 2005; McKay & Weiss, 2001; McLellan et al., 1994; Moos, Moos, & Finney, 2001; Siqueland et al., 1998; also see Hawkins et al., 2007 for review). The role of treatment processes has also been examined including client-counselor alliance (Connors, Carroll, DiClemente, Longabaugh, & Donovan, 1997; Joe, Simpson, & Broome, 1999) and clients’ ratings of their satisfaction with treatment (Carlson & Gabriel, 2001; Hser et al., 2004; Villafranca et al., 2006). Not surprisingly in the context of the complex processes of behavior change and therapeutic engagement, “there is no single domain that independently predicts treatment retention” (Hellemann et al., 2009, p. 63). To date, the growing empirical knowledge base on factors associated with treatment attrition “has resulted in minimal impact on retention in addiction treatment services” (Hawkins et al., 2007, p. 208).

1.3 Study objectives: Understand your customer

A number of treatment provider systems nationwide have formed the Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment (NIATx) (Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment (NIATx), 2005b) to identify system-level barriers to access to, engagement and retention in substance abuse services, and to implement strategies to overcome these challenges. Looking to business models for guidance, they have identified five principles to guide their efforts. The first principle is “Understand and involve the customer” (Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment -NIATx, 2005a): “Taking the time to involve customers, get their reactions to and advice about improvements, and prepare them for anticipated changes are all ways that substance abuse treatment agencies can better meet their customers’ unique needs.” The perspective of substance users remains largely ignored in services research (Carlson, 2006; Tsogia, Copello, & Orford, 2001) although researchers have noted that “patient perspectives on treatment may have a role in treatment outcomes and should be explored as a dimension of the treatment process” (Lee et al., 2007, p. 313). With a few recent exceptions (Orford et al., 2006; Orford, Hodgson, Copello, Wilton, & Slegg, 2008; Orford et al., 2006), studies examining patients’ experiences use structured instruments (Kasarabada, Hser, Boles, & Huang, 2002; Lee et al., 2007). This is a suboptimal approach because it limits the information collected to the domains included in the inventory – that is, the researcher dictates the topics/services that clients mention or rate. Qualitative methods that use an open-ended format and record participants’ verbatim answers are much more labor intensive but the resulting information is more useful because it taps into individual participants’ experiences in their own words, helping to identify topics and processes that may not have been previously identified or addressed. The goals of this qualitative study are to examine clients’ reasons for leaving treatment as well as what, if anything, could have been done to retain them in services. The latter appears not to have been examined previously although the information has the potential of informing service development and policy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Setting and recruitment

The study was conducted in the context of a prospective investigation of 12-step participation after outpatient treatment. Participants (N = 278) were recruited at two publicly-funded state licensed intensive outpatient treatment programs in New York City between September 2003 and December 2004. As detailed elsewhere (Laudet, Stanick, & Sands, 2007), the programs were similar in administrative structure, therapeutic orientation, services and client characteristics (e.g., dependence severity, prior exposure to treatment and to 12-step meetings). Both programs required daily participation during weekdays. The study was introduced to clients during their orientation session (immediately after official admission). Clients who expressed interest in participating met with the research interviewer who explained the voluntary nature of the study and what participation in the study entailed; the signed informed consent procedure was then administered and the baseline (BL) interview was conducted, lasting two and a half hours on average. This first interview was conducted within two weeks of admission and clients were re-interviewed when services ended (DIS) regardless of the reason (treatment completion, transfer or dropping out); participants received $30 for each of the interviews. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of NDRI and of the two participating agencies and we obtained a certificate of confidentiality from the funding agency.

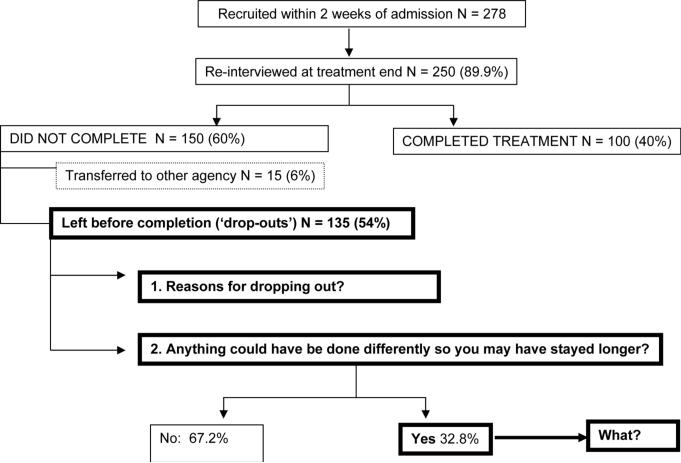

Figure 1 provides a graphic representation of the study design and of the sequence of questions that were asked to obtain the data presented here. Two hundred and fifty participants were re-interviewed at treatment end (89.9% retention); they were asked whether they had completed treatment and if not, the circumstances of their leaving before completion, using SAMHSA's discharge status categories (transferred to other facility, administrative discharge, dropped out and ‘other’); these self-reported data were checked against clinic records (with client consent). Clients who did not complete the course of treatment and provided a reason other than ‘transferred to other facility’ were considered to have dropped out of treatment. Forty percent of participants completed treatment; of the 60% who did not, 6% were transferred elsewhere, thus 54% met our criteria for ‘drop-outs’ (N =135) and constitute the sample for this study.

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of study design and domains

2.2 Data collection procedures and measures

Study data were collected though semi-structured instruments administered via computer assisted-interviewing using the QDS software (Nova Research, Inc.). The instrument consisted of standardized scales and open-ended questions designed to obtain information about participants’ experiences and beliefs in their own words. The interviewers were trained in both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods including how to probe respondents when the initial response to an open ended question is vague, and how to record participants’ answers verbatim in the QDS software. The questions used to collect information for this study are as follows:

Reasons for dropping out of treatment: “What is/are the most important reason(s) why you dropped out of the program?”

“Is there anything the program could have done differently so that you would have continued attending?” (Dichotomous answer category: yes/no).

Participants who answered the previous question in the affirmative were asked: “What could have been done differently so that you would have continued attending?”

2.3 Qualitative data coding

Codes for the verbatim answers to questions (a) and (c) above were developed on the first 30 completed interviews; based on a subsample of 35 randomly selected instruments coded by two independent researchers (the first author and a clinically trained collaborator), inter-rater reliability was .93; up to three answers were coded for each question so that the findings presented in subsequent tables add to over hundred percent.

3.1 Sample descriptives

Participants were 57.2% males with an average age of 39 years (range 19 to 60, Std. Dev = 9.0); most were from ethnic minority groups (62% African-American, 21.6% Caucasian and 16.4% of mixed ethnicities); 36.1% reported being Hispanic. Mean educational attainment was 10.5 years; 73.7% reported government assistance as their primary income source. Almost all (92.4%) cited multiple problem substances with a mean of 3.6 substances including crack (44.4%), alcohol (18.4%), heroin (14.4%), marijuana (14%), cocaine other than crack (7.6%), and 1.2 % ‘other;’ 79.2% had received substance abuse services prior to the index episode; these individuals reported a mean of 5.8 previous episodes.

As shown in Figure 1, 40% of clients completed treatment; of the 60% who left before completion, 6% were transferred to a different agency, 54% (N =135) had dropped out. As reported elsewhere, at baseline, completers and drop outs did not differ in past year Addiction Severity Index (ASI) scores, in prior participation in treatment or 12-step groups, readiness to change, or in the number of areas where they reported needing services. Relative to non-completers, completers were older (40.7 vs. 37.4, p<.05), more likely to be females and African Americans (vs. Caucasian; Stanick, Laudet, & Sands, 2008).

3.2 Reasons for dropping out of treatment

Table 1 presents reasons for leaving treatment. Key themes follow with illustrative quotes:

Table 1.

Reasons for leaving treatment in descending order of frequency (N = 135)1

| Dislike of one or more aspect of program | 31.8% |

| Staff | 13.7% |

| Overall dislike | 12.8% |

| Other clients | 4.3% |

| Program rules | 1.0% |

| Program interferes with other activities | 18.8% |

| Job | 11.1% |

| Interferes - general | 4.3% |

| School | 1.7% |

| Time needed to find other services | 1.7% |

| Using drugs/relapsed | 13.7% |

| Practical issues | 12.1% |

| Program location | 11.1% |

| No child care | 1.0% |

| Does not want/need help | 12.0% |

| Personal issues unrelated to program | 11.9% |

| Family | 5.1% |

| Personal | 3.4% |

| Physical health | 3.4% |

| Finances | 8.6% |

| No money | 6.0% |

| Insurance problems | 2.6% |

| Program not helpful | 8.5% |

Total > 100% because up to three answers were coded

Dislike of some aspect of program (31.8%)

“I didn't like the services,” “the program had no structure,” “I didn't think there was anything there for me!” “the counselor had no respect for his clients and he doesn't give support to his clients when they need it,” “I felt I was railroaded by my counselor and the program's false impression of helping me out” and “the counselor put me down.”

Program interferes with other activities (18.8%)

” I was about to be homeless and I had to find a place,” “I couldn't do certain things like work because I was at the program most of the day”

Substance use (13.7%)

“I was dipping and dabbing with my drinking so I just left,” and “I was still getting high and I didn't want to face my counselor.”

Practical issues (12.1%)

“My wife and I had no babysitter for the two boys,” and “I didn't have transportation.”

Does not want/need help (12%)

“I got tired of going to the program,” and “I was not ready.”

Personal issues (11.9%)

“My mother is sick,” and “I had a domestic problem situation.”

Finances (8.6%)

”My Medicaid ran out and they told me to leave,” and “I didn't have the transportation to go there regularly and I really needed money for food.”

Program not helpful (8.5%)

“I was seeing the same thing everyday, heard things I already knew,” “it did more harm than good,” “they did not give me what I need.”

3.3 What could the program have done differently?

Two-thirds of the clients who left treatment (67.2%) said that nothing could have been done by the program to keep them engaged in services. The answers of the remaining third are presented in Table 2 and representative quotes follow.

Table 2.

What could program have done differently to enhance client engagement (N = 44)

| Practical help – social service needs | 54.2% |

| Better address individual service needs | 15.4% |

| Employment/education/training | 10.3% |

| Car fare/transportation | 7.7% |

| More helpful/relevant group topics | 5.2% |

| Include client in treatment plan decisions | 5.2% |

| Housing | 2.6% |

| Child care | 2.6% |

| Legal help | 2.6% |

| Insurance issues | 2.6% |

| Staff | 25.8% |

| Better staff/counselors -general | 12.8% |

| More empathic (less confrontational) staff | 5.2% |

| Be there for me; believe in me, have faith, trust me | 5.2% |

| Better guidance, direction, support | 2.6% |

| Flexibility/range of hours | 20.0% |

Need for social services (54.2%)

[They could have] “speeded up my vocational process,” “helped me find a training or a job,” “helped me get out of the shelter and help me with an apartment,” “given me progress reports for court on time!” “given me a pantry listings for food,” and “I could have stayed if had been able to have my child attend [the program] during my treatment.”

More supportive staff (25.8%)

“If I could change counselor, one who was able to talk to me and not look away from me,” “If the counselor wouldn't turn their face and deal with the matter,” “They could have helped me do the right thing, encourage me” and “They could have trusted me, have faith in me.”

Flexibility (20%)

[They could have] “Adapted a schedule of treatment to accommodate my work hours,” “made the time for me more convenient and accessible so I could have gone to work and gone to the program.”

4. Discussion

4.1 Reprise of key findings

We set out to examine outpatient clients’ reasons for leaving treatment and to find out whether and what they felt the programs could have done differently to keep them engaged in services. Participants were members of under-served minorities recruited in inner city neighborhoods in New York City. The completion rate of 40% is on par with the national average of 36% for outpatient services (SAMHSA Treatment Episode Data Set 2005, 2008). Reasons for leaving treatment were: disliking the program, interference with other activities, substance use, practical considerations, not wanting help, personal issues, finances and not finding the services helpful. Among the 33% of dropouts who said something could have been done differently to retain them in services, unmet social service needs was cited most (54.2%) followed by wanting more supportive staff and greater scheduling flexibility. Thus for heuristic purposes, key barriers to retention in this sample can be categorized into program- and client-related factors.

4.2 Study limitations

Before discussing study findings, several study limitations must be noted that deserve consideration when interpreting results. First, findings are necessarily based on clients’ self-reports. Thus it may be argued that clients who are ‘treatment resistant’ or ‘in denial’ (i.e., those who leave treatment before completion) may look for external reasons to drop out of services they did not really want, did not intend to complete, or from which they expected ‘the moon’ (i.e., to magically solve a plethora of complex and long-standing life problems), rather than taking responsibility for using available services and improving their lives. Second, the study sample is relatively small (N = 250) and was recruited at two programs in one city; in particular, the subsample of participants who provided data about what the programs could have done differently is a small (N = 44) and may not represent clients who leave treatment in other programs, modalities, settings or geographical locations. However, the retention rate in this study is consistent with the national average and the issues identified here have been reported in other studies conducted in different contexts. Therefore we are reasonably confident that in spite of these limitations, our results, though not the final word on the topic, are of sufficient significance clinically and in terms of program development, to warrant further investigation.

4.3 Treatment program-level barriers to retention

These factors, making up the bulk of findings, included dissatisfaction with some aspect(s) of the program, especially counselors, the need for social services, and greater scheduling flexibility because program attendance interferes with other important activities (e.g., work or school). Substance abuse treatment programs serve clients whose addiction ‘career’ has often resulted in impairments in all areas of functioning. While the immediate goal of treatment is to promote abstinence, patients’ goals span all ‘addiction-related areas.’ In this cohort, the top five priorities at intake were abstinence (50.2%), get a job (28.3%), get education or training (24.1%), children-related mentions (e.g., get children back, 18.7%), and housing (17.7%). Thus abstinence may best be regarded as a means to an end rather than an end in itself. McLellan and colleagues have noted that improvements in personal health and social function are key treatment goals (McLellan, McKay, Forman, Cacciola, & Kemp, 2005). It has been argued that what clients bring into treatment is often less important than what they find there (Fiorentine, Nakashima, & Anglin, 1999). Clients engage in treatment when they believe that it will address their problems: Positive treatment experiences such as relationships with counselors (see below), satisfaction with treatment, and receipt of needed services predict longer retention and better outcomes (Fiorentine et al., 1999; McLellan et al., 1996; Simpson et al., 1995; Strauss & Falkin, 2000). Given the breath and magnitude of functional impairments resulting from chronic substance dependence, it is no surprise that clients need and expect services to address (and improve) not only their primary symptom (i.e., substance abuse) but also and perhaps more importantly, the many life areas that have deteriorated as a direct or indirect result of substance use. Programs must not only provide services that meet the diversity of clients’ needs to rebuild their lives, they must also recognize that though often critical, treatment is but a small part of a client's life. Once they made the difficult decision to ‘turn their life around,’ substance users are often eager to ‘make up for lost time’ which for most, begins with securing employment or the training to do so (education); these domains are also important to society and to service payers (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008). Working and going to school typically requires some daytime availability. Our findings suggest that if required to choose between attending treatment or going to work or school, clients may forego the former. This reduces the effectiveness of services.

The relationship with counselors is among the most important system-level influences on treatment retention and outcome (Najavits, 2002; Redko et al., 2007), often more influential than either treatment type or patients’ characteristics. (McLellan, Woody, Luborsky, & Goehl, 1988; Najavits et al., 2000; Project MATCH Research Group, 1998). Patients’ perceptions of their counselors as trusting, accepting, and understanding predict significantly longer retention in outpatient treatment (Hatcher & Barends, 1996; Jinks, 1999; Kasarabada et al., 2002) and influence subsequent help seeking (Redko et al., 2007) which is critical since most clients need multiple treatment episodes (Dennis et al., 2005; Laudet et al., 2007). Counselors’ jobs are challenging; they must engage in treatment clients who are not always motivated to be there (see below), many of whom have prior experiences with treatment and have likely acquired strategies to ‘deal’ with the program staff, to elude rules, etc. Moreover, clinicians rarely see their successes - clients whose life has improved significantly as a result of treatment. In this context, maintaining an attitude that conveys trust, acceptance, and understanding is a ‘job requirement’ that seems beyond the capacity of mere mortals; yet it is likely to be as critical as more technical skills, especially when serving ambivalent clients whose counselor's trust may make the difference between stable engagement in services (and presumably, more favorable long-term outcomes) and early attrition.

4.4. Individual-level barriers to retention

Problem recognition and substance use are two key client-level barriers to retention; they can, to some extent, be regarded as two sides of the same coin. Problem recognition is key to help-seeking (Jordan & Oei, 1989) and to initiating behavior change (Evans, Li, & Hser, 2008; Lieberman & Massey, 2008; Orford et al., 2006; Redko et al., 2007; Sobell, Ellingstad, & Sobell, 2000; Tsogia et al., 2001). In 12-step recovery, it is the first step to initiating change: “Admitted that we were powerless over alcohol, that our lives had become unmanageable” (Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, 1939−2001). Most (95.5%) of the estimated 21 million individuals who do not receive needed services for substance use problems in the US do not recognize the need for help (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006), a phenomenon referred to as ‘the denial gap.” In this study, in addition to the 12% of clients citing not wanting or needing help as a reason for leaving treatment, two-thirds of drop-out reported that nothing could have been done to retain them in services. We cannot determine with certainty the extent to which these respondents did not recognize the need for help vs. other obstacles to retention but it is likely to be significant.

Using substances while enrolled in treatment is at times grounds for administrative discharge (White, Scott, Dennis, & Boyle, 2005), a practice that a naïve observer could interpret as turning away a patient for ‘proving’ he/she has the chronic, relapse-prone condition for which treatment was initiated. Even when not cause for discharge, substance use is too often regarded by programs as a sign of ‘non compliance’ that turns away from services, clients who need it the most, as evidenced in these statements: e.g., “I was still getting high and I didn't want to face my counselor,” “I was dipping and dabbing with my drinking so I just left.” The latter implies a logical sequence whereby substance use ineluctably leads to services ending (either leaving or been discharged). Abstinence is the goal of treatment in the US; it is, by all accounts, a desirable outcome and a requirement for the broader goal of ‘recovery’ (Belleau et al., 2007; Laudet, 2007; McLellan et al., 2005). However, most substance users embrace that goal as a last resort –after attempts at moderation and other strategies failed (Burman, 1997); recognizing the need for abstinence takes time for most. Even when clients recognize the need for help and embrace an abstinence goal, abstinence is not a guarantee; when it is reached, it is not secure: relapse is regrettably more often the norm than the exception –addiction is after all, often a ’relapse prone condition.’ Behavior change requires coping strategies that many clients lack and in outpatient settings, clients continue to live in an environment that is too often conducive to substance use. Therefore substance use during treatment is likely. Nonetheless, having clients in a clinical setting presents an opportunity to engage them in the change process including enhancing motivation for change, regardless of their current level of problem recognition– that is, even if they are ‘in denial’ and/or not yet abstinent.

4.5 Implications of findings for clinical practice, service development and research

So what are treatment programs to do? Recent findings suggest that many clients know (explicitly or otherwise) very early on whether or not they are ready to engage in services and to complete treatment (Stanick et al., 2008). What clients find at the program during this initial period likely influences subsequent outcomes including retention. Opening the dialogue with clients starting at intake is critical to identifying reasons for help-seeking, needs and expectations, experiences with and attitudes about treatment, perceived likelihood of completion, and to explore and address possible barriers to retention. This process must be ongoing as needs may change, and it must be a dialogue (a partnership) where clients feel truly involved in their treatment plan and where the shared goal of restoring healthy functioning allows for clients to work on ‘getting a life’ (e.g., work) while they acquire the motivation and skills to desist from substance use.

In terms of service development, the most compelling approach to addressing a condition that impairs all areas of functioning is to meet all service needs in a coordinated and integrated fashion, that is, to treat the person rather than the symptoms. A promising service model based on the recognition that recovery, the ultimate goal of treatment, “is about building a full, meaningful, and productive life” (Clark, 2007) is gradually taking hold (Kaplan, 2008). This model, Recovery-oriented Systems of Care (ROSC),1 provides multi-system, person-centered continuity of care where a comprehensive menu of coordinated services and supports is tailored to individuals’ recovery stage, needs and chosen recovery path (Clark, 2007). ROSC would address many, though by no means all, the barriers to treatment retention identified here. The ROSC model needs to be empirically evaluated to assess not only effectiveness (including in terms of retention) but also cost effectiveness. It is our hope that future studies conducted in service settings, regardless of prevailing modality or care model, will examine clients’ reasons for leaving treatment as well as barriers to retention and unmet service needs. Only by ‘knowing our customer’ can we reasonably hope to develop and provide services that attract and retain those who need it.

Acknowledgments

■ National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant DA015133 supported this work.

■ The author gratefully acknowledges study participants who generously shared their experiences with us for this project and the staff of the collaborating agencies.

■ Beth Moses, MSW, collaborated with the author in developing codes and coded verbatim answers to the open-ended questions.

■ Portions of this study were poster-presented in preliminary form at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence in San Juan, Porto Rico, in June 2008.

Footnotes

Reference List

- Alcoholics Anonymous World Services . Alcoholics Anonymous: The Story of How Many Thousands of Men and Women have Recovered from Alcoholism. Alcoholics Anonymous World Services Inc.; New York: 19392001. [Google Scholar]

- Belleau C, DuPont R, Erickson C, Flaherty M, Galanter M, Gold M, Kaskutas L, Laudet A, McDaid C, McLellan AT, Morgenstern J, Rubin E, Schwarzlose J, White W. What is recovery? A working definition from the Betty Ford Institute. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33(3):221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman S. The challenge of sobriety: natural recovery without treatment and self-help groups. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:41–61. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MJ, Gabriel RM. Patient satisfaction, use of services, and one-year outcomes in publicly funded substance abuse treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(9):1230–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson RG. W. Miller, & K. Carroll Rethinking substance abuse: What science shows and what we should do about it. Guilford Publications; New York: 2006. Ethnography and applied substance misuse research: Anthropological and cross-cultural factors. pp. 201–219. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM. Enhancing retention in clinical trials of psychosocial treatments: Practical strategies. NIDA Research Monograph. 1997;165:4–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark W. Recovery as an Organizing Concept [Web Page] 2007 URL http://www.glattc.org/Interview%20With%20H.%20Westley%20Clark,%20MD,%20JD,%20MPH,%20CAS,%20FASAM.pdf [2008, February 7]

- Connors GJ, Carroll KM, DiClemente CC, Longabaugh R, Donovan DM. The therapeutic alliance and its relationship to alcoholism treatment participation and outcome. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65(4):588–98. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council C. Health services utilization by individuals with substance abuse and mental disorders [DHHS Publication No.SMA 043949, Analytic Series A-25] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk R, Foss MA. The duration and correlates of addiction and treatment careers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28(Suppl 1):S51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E, Li L, Hser YI. Treatment entry barriers among California's Proposition 36 offenders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney JW, Moos R. Psychosocial treatments for alcohol use disorders. In: Nathan P, Gorman J, editors. A Guide to Treatments That Work. University Press; NY: Oxford: 1998. pp. 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentine R, Nakashima J, Anglin MD. Client engagement in drug treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1999;17(3):199–206. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(98)00076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Joshi V, Hser YI. Program variation in treatment outcomes among women in residential drug treatment. Eval Rev. 2000;24(4):364–83. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0002400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher RL, Barends AW. Patients’ view of the alliance of psychotherapy: exploratory factor analysis of three alliance measures. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(6):1326–36. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins EJ, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR. Concurrent monitoring of psychological distress and satisfaction measures as predictors of addiction treatment retention. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;35(2):207–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemann G, Conner B, Anglin MD, Longshore D. Seeing the trees despite the forest: Applying recursive partitioning to the evaluation of drug treatment retention. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(1):59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Evans E, Huang D, Anglin DM. Relationship between drug treatment services, retention, and outcomes. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(7):767–74. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.7.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Anderson J. Overview of 5-year followup outcomes in the drug abuse treatment outcome studies (DATOS). J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;25(3):125–34. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinks G. Intentionality and awareness: A qualitative study of clients’ perceptions of change during longer term counselling. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 1999;12(1):57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, Simpson DD, Broome KM. Retention and patient engagement models for different treatment modalities in DATOS. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;57(2):113–25. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan M, Oei C. Help-seeking behaviour in problem drinkers: a review. British J. Addict. 1989;84(9):979–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan L. The role of recovery support services in recovery-orienged systems of care: DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 08−4315. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kasarabada ND, Hser YI, Boles SM, Huang YC. Do patients’ perceptions of their counselors influence outcomes of drug treatment? J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23(4):327–34. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Moos R. Dropout from 12-step self-help groups: prevalence, predictors, and counteracting treatment influences. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24(3):241–50. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet A, Becker J, White W. Don't wanna go through that madness no more: Quality of life satisfaction as predictor of sustained substance use remission. Subs, Use Misuse. 2009;44(2):227–252. doi: 10.1080/10826080802714462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet A, Stanick V, Sands B. The effect of onsite 12-step meetings on post-treatment outcomes among polysubstance-dependent outpatient clients. Evaluation Review. 2007;31(6):613–646. doi: 10.1177/0193841X07306745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet AB. What does recovery mean to you? Lessons from the recovery experience for research and practice. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;33(3):243–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Longabaugh R, Baird J, Abrantes AM, Borrelli B, Stein LA, Woolard R, Nirenberg TD, Mello MJ, Becker B, Carty K, Clifford PR, Minugh PA, Gogineni A. Do patient intervention ratings predict alcohol-related consequences? Addict Behav. 2007;32(12):3136–41. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman D, Massey S. Pathways to Change: The Effect of a Web Application on Treatment Interest. American Journal on Addictions. 2008;17(4):265–270. doi: 10.1080/10550490802138525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Nwakeze PC, Demsky SY. Pre- and in-treatment predictors of retention in methadone treatment using survival analysis. Addiction. 1998;93(1):51–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch LA, Stephens MA, Mudric T, Strain EC, Bigelow GE, Johnson RE. Predictors of outcome in LAAM, buprenorphine, and methadone treatment for opioid dependence. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;13(4):293–302. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.13.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson ME, Del Boca FK, Carroll KM, Cooney NL, DiClemente CC, Donovan D, Kadden RM, McRee B, Rice C, Rycharik RG, Zweben A. Compliance with treatment and follow-up protocols in project MATCH: predictors and relationship to outcome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22(6):1328–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Weiss RV. A review of temporal effects and outcome predictors in substance abuse treatment studies with long-term follow-ups. Preliminary results and methodological issues. Eval Rev. 2001;25(2):113–61. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0102500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Alterman AI, Metzger DS, Grissom GR, Woody GE, Luborsky L, O'Brien CP. Similarity of outcome predictors across opiate, cocaine, and alcohol treatments: role of treatment services. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62(6):1141–58. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.6.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, McKay JR, Forman R, Cacciola J, Kemp J. Reconsidering the evaluation of addiction treatment: from retrospective follow-up to concurrent recovery monitoring. Addiction. 2005;100(4):447–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Woody GE, Luborsky L, Goehl L. Is the counselor an ”active ingredient” in substance abuse rehabilitation? An examination of treatment success among four counselors. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988;176(7):423–30. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198807000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Woody GE, Metzger D, McKay J, Durrell J, Alterman AI, O'Brien CP. Evaluating the effectiveness of addiction treatments: reasonable expectations, appropriate comparisons. Milbank Q. 1996;74(1):51–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Protective resources and long-term recovery from alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86(1):46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS, Finney JW. Predictors of deterioration among patients with substance-use disorders. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57(12):1403–19. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM. Clinicians’ views on treating posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22(2):79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Crits-Christoph P, Dierberger A. Clinicians’ impact on the quality of substance use disorder treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35(12−14):2161–90. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment (NIATx) The Five Key Principles [Web Page] 2005a URL https://niatx.net/Content/ContentPage.aspx?NID=17 [2008a, July 8]

- Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment (NIATx) NIATx Overview [Web Page] 2005b URL https://niatx.net/Content/ContentPage.aspx?NID=9 [2008b, July 8]

- Orford J, Hodgson R, Copello A, John B, Smith M, Black R, Fryer K, Handforth L, Alwyn T, Kerr C, Thistlethwaite G, Slegg G. The clients’ perspective on change during treatment for an alcohol problem: qualitative analysis of follow-up interviews in the UK Alcohol Treatment Trial. Addiction. 2006;101(1):60–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orford J, Hodgson R, Copello A, Wilton S, Slegg G. To what factors do clients attribute change? Content analysis of follow-up interviews with clients of the UK Alcohol Treatment Trial. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orford J, Kerr C, Copello A, Hodgson R, Alwyn T, Black R, Smith M, Thistlethwaite G, Westwood A, Slegg G. Why people enter treatment for alcohol problems: Findings from the UK Alcohol Treatment Trial pre-treatment interviews. J Subst Abuse. 2006;11(3):161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three year drinking outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;226:1300–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redko C, Rapp RC, Carlson RG. Pathways of Substance Users Linking (Or Not) With Treatment. J Drug Issues. 2007;37(3):597–618. doi: 10.1177/002204260703700306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Broome KM, Hiller ML, Knight K, R.-S. G. A. Program diversity and treatment retention rates in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11(4):279–293. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Fletcher BW, Hubbard RL, Anglin MD. A national evaluation of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(6):507–14. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.6.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Rowan-Szal G, Greener J. Client engagement and change during drug abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse. 1995;7(1):117–34. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siqueland L, Crits-Christoph P, Frank A, Daley D, Weiss R, Chittams J, Blaine J, Luborsky L. Predictors of dropout from psychosocial treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;52(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Ellingstad TP, Sobell MB. Natural recovery from alcohol and drug problems: methodological review of the research with suggestions for future directions. Addiction. 2000;95(5):749–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95574911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanick V, Laudet A, Sands B. Will I stay or will I go? Role of early treatment experiences in predicting attrition.. 70th Scientific Meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence..2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stark M. Dropping out of substance abuse treatment: a clinically-oriented review. Clinical Psychology Review. 1992;12:93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss SM, Falkin GP. The relationship between the quality of drug user treatment and program completion: understanding the perceptions of women in a prison-based program. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35(12−14):2127–59. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2006. (Report No. NSDUH Series H-25,DHHS Publication No. SMA 04−3964) [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National Outcomes Measures (NOMS): A message from the Administrator [Web Page] 2008 URL http://www.nationaloutcomemeasures.samhsa.gov/ [2008, February 7]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) 2004 . Discharges from substance abuse treatment services, DASIS Series: S-35, DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 06−4207. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) 2005 . Discharges from substance abuse treatment services, DASIS Series. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tsogia D, Copello A, Orford J. Entering treatment for substance misuse: A review of the literature. Journal of Mental Health. 2001;10(5):481–499. [Google Scholar]

- Villafranca SW, McKellar JD, Trafton JA, Humphreys K. Predictors of retention in methadone programs: a signal detection analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83(3):218–24. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace AE, Weeks WB. Substance abuse intensive outpatient treatment: does program graduation matter? J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27(1):27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White W, Scott C, Dennis M, Boyle M. It's time to stop kicking people out of addiction treatment. Counselor. 2005;6(2):12–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Friedmann PD, Gerstein DR. Does retention matter? Treatment duration and improvement in drug use. Addiction. 2003;98(5):673–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]