Abstract

Background

The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), a population-based prospective cohort study, has been used to identify major risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease and stroke in the elderly.

Objective

To assess the external validity of the CHS.

Research Design

Comparison of the CHS cohort to a national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries and to Medicare beneficiaries residing in the CHS geographic regions.

Subjects

CHS participants and a 5% sample of Medicare beneficiaries.

Measures

Demographic and administrative characteristics, comorbid conditions, resource use, and mortality.

Results

Compared to both Medicare cohorts, the CHS cohort was older and included more men and African American participants. CHS participants were more likely to be enrolled in Medicare managed care than beneficiaries in the national Medicare cohort. Compared to the Medicare cohorts, mortality in the CHS was more than 40% lower at 1 year, approximately 25% lower at 5 years, and approximately 15% lower at 10 years. There were minimal differences in comorbid conditions and health care resource use.

Conclusion

The CHS cohort is comparable to the Medicare population, particularly with regard to comorbid conditions and resource use, but had lower mortality. The difference in mortality may reflect the CHS recruitment strategy or volunteer bias. These findings suggest it may not be appropriate to project absolute rates of disease and outcomes based on CHS data to the entire Medicare population. However, there is no reason to expect that the relative risks associated with physiologic processes identified by CHS data would differ for nonparticipants.

Keywords: Cardiovascular Diseases, Cohort Studies, Epidemiologic Methods, Health Services Research, Medicare, United States

Introduction

Population-based, prospective cohort studies are important for answering epidemiologic questions about the development of disease. They can track individuals without disease over time, establish a sequence of events before disease develops, measure multiple exposures of interest in a standardized fashion, and observe several outcomes in great detail. To minimize costs and increase efficiency, participants in prospective cohort studies are often recruited based on accessibility, such as geographic region.1 The advantage of geographic restriction must be weighed against the disadvantage of limiting the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability to the entire population.

The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) is a population-based, prospective cohort study of persons aged 65 and older.2 The CHS has identified major risk factors and physiologic processes associated with the onset and progression of cardiovascular disease and stroke in the elderly.3–10 Although the internal validity of the CHS has been examined previously,11 the external validity of the CHS has not been assessed. In this study, we sought to determine whether the CHS is representative of Medicare beneficiaries nationally and of Medicare beneficiaries residing in the geographic regions sampled by the CHS. Specifically, we examined whether the CHS cohort was comparable to two Medicare cohorts at baseline with regard to patient characteristics, comorbid conditions, and resource use and as measured by mortality at 10 years.

Methods

Data Sources

Participants in the CHS were randomly sampled from the Medicare eligibility list of the Health Care Financing Administration, now the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Detailed methods for identifying and recruiting participants into the CHS have been described elsewhere.12 In brief, 5,888 participants aged 65 years and older were recruited from four geographic regions: Forsyth County, North Carolina; Sacramento County, California; Washington County, Maryland; and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.13 Individuals were excluded from the CHS cohort if they were “institutionalized (including nursing homes), in a hospice program or under active treatment for cancer…, were confined to a wheelchair in the home, were cognitively unable to sign an informed consent, or did not expect to remain in the community for three years.”13 Individuals were also excluded if they required a proxy respondent at the baseline interview. In addition to individuals randomly sampled from the Medicare eligibility list, those who were aged 65 years or older and were living in the same household were also recruited to participate if they met the inclusion criteria.12 Recruitment of the first cohort began in 1989 and was completed in 1990. Of the 11,955 individuals sampled during the first recruitment phase, 1,062 were ineligible and 5,201 were enrolled.12 Recruitment of a second cohort comprising African American beneficiaries began in 1992 and was completed in 1993. A total of 687 African American participants were enrolled during the second recruitment phase.13 Once enrolled, participants were contacted semiannually through 1999 in encounters that alternated between clinic examinations and telephone follow-up, where information about cardiovascular events, changes in risk factors and functional status, and hospitalizations was collected.14 Since 1999, the CHS has continued to follow participants with semiannual telephone calls.2

Medicare is the largest purchaser of health care and provides insurance to nearly 40 million elderly Americans.15 Medicare Part A provides coverage for inpatient care provided in hospitals, short-term stays in skilled nursing facilities, hospice care, and post-acute home health care. Medicare Part B provides coverage for outpatient services, including physician visits and other medical services, outpatient hospital care, and some preventive services. The Medicaid program provides free or low-cost health care coverage for low-income Americans, including Medicare beneficiaries.16 For this study, we obtained from CMS all Medicare Part A inpatient claims, all Medicare Part B outpatient and physician/carrier claims, and the corresponding denominator files for CHS participants. The denominator files include beneficiary identifiers, dates of birth, sex, race/ethnicity, dates of death, and information about program eligibility and enrollment. Information in the denominator files is received annually, even if no claims were generated in a given year. CMS selected matching claims for CHS participants on the basis of social security number, birth date, and sex. For purposes of comparison, we also obtained CMS claims data and denominator files for a 5% sample of Medicare beneficiaries from 1992 forward. The 5% sample is a systematic, quasi-random sample constructed by CMS using two-digit combinations from beneficiaries’ health insurance claim number.17

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the institution where the study was conducted.

Study Population

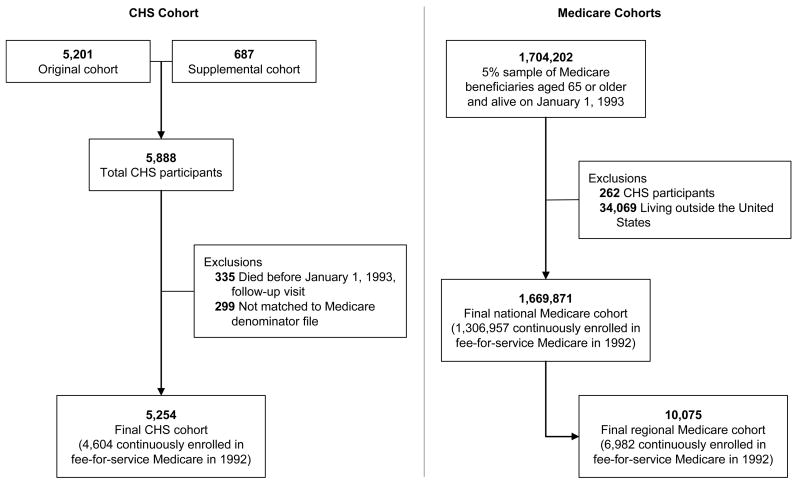

We created two Medicare cohorts retrospectively from the Medicare 5% sample (Figure 1). The first was a national cohort of beneficiaries aged 65 years or older on January 1, 1993. We excluded beneficiaries who were not living in the United States and beneficiaries identified as participants in the CHS. The second was a regional cohort composed of beneficiaries from the national cohort who were living in one of the CHS recruitment regions on January 1, 1993. We identified these beneficiaries by state and county of residence for the North Carolina, California, and Maryland regions. The Pennsylvania region was not county-based, so we used observed ZIP codes for CHS participants to select beneficiaries in that region. We limited the CHS cohort to participants who were alive on January 1, 1993 (the year of final recruitment of the second cohort) and could be matched to the Medicare denominator file (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Development of the CHS and Medicare Cohorts Used in the Analysis

Demographic and Administrative Characteristics

Information in the denominator files allowed us to compare demographic and administrative characteristics in the CHS cohort with the two Medicare cohorts as of January 1, 1993. We compared age, sex, and race/ethnicity, as well as whether beneficiaries had Medicare Part B coverage, were enrolled in Medicare managed care or traditional fee-for-service Medicare, had been diagnosed with end-stage renal disease, were concurrently enrolled in Medicaid, or were originally entitled to Medicare due to disability. We determined Medicaid enrollment by identifying the beneficiary’s state buy-in status, which indicates whether benefits received under Medicare Part A, Medicare Part B, or both were funded by a state Medicaid program.

Comorbid Conditions

Data on comorbid conditions were available in the Medicare inpatient, outpatient, and carrier/physician files. All three files contain beneficiary identifiers and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes.18 We identified comorbid conditions by using previously described coding algorithms.19,20 Specifically, we searched all claims generated in the calendar year before January 1, 1993, for evidence of myocardial infarction (ICD-9-CM codes 410.x, 412.x), congestive heart failure (398.91, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13, 404.91, 404.93, 425.4–425.9, 428.x), peripheral vascular disease (093.0 437.3, 440.x, 441.x, 443.1–443.9, 47.1, 557.1, 557.9, V43.4), cerebrovascular disease (362.34, 430.x–438.x), dementia (290.x, 294.1, 331.2), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (416.8, 416.9, 490.x–505.x, 506.4, 508.1, 508.8), rheumatic disease (446.5, 710.0–710.4, 714.0–714.2, 714.8, 725.x), peptic ulcer disease (531.x–534.x), diabetes mellitus (250.x), renal disease (403.01, 403.11, 403.91, 404.02, 404.036, 404.12, 404.13, 404.92, 404.93, 582.x, 583.0–583.7, 585.x, 586.x, 588.0, V42.0, V45.1, V56.x), cancer (196.x–199.x), stroke/transient ischemic attack (433.x1 434.x1 435.x 436 437.1x 437.9x 438.x), coronary heart disease (410.x–414.x 429.2 V45.81), hypertension (401.x–405.x 437.2), or valvular heart disease (394.x–397.x 398.9 42.4x V42.2 V43.3). For comparisons of comorbid conditions, we selected only beneficiaries who were continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare for one calendar year before January 1, 1993. This restriction was necessary because comparisons of comorbid conditions require data from claims that are not available for managed care enrollees.

Resource Use and Costs

We obtained information on resource use and costs to Medicare in the calendar year before January 1, 1993. We characterized resource use as the mean number of inpatient stays, outpatient visits, medical evaluation and management visits, and cardiology evaluation and management visits per beneficiary. We defined an inpatient stay as an episode of inpatient care made up of overlapping or adjacent inpatient claims. We defined outpatient visits as distinct encounters in an outpatient institutional setting, limited to one outpatient visit per day. Medical evaluation and management visits were determined by Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes21 992xx, 993xx, and 994xx in the physician/carrier claims file. Cardiology evaluation and management visits were determined by the specialty of the physician listed on the claim. Costs to Medicare are recorded as the reimbursement amounts on each claim (ie, paid claims, not charges). We report mean total costs, inpatient costs, outpatient costs, and physician costs per beneficiary. All costs are expressed in 1992 US dollars. For comparisons of resource use and costs, we selected only beneficiaries who were continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare for one calendar year before January 1, 1993. Again, this restriction was necessary because comparisons of resource use and costs require data from claims that are not available for managed care enrollees.

Mortality

We compared all-cause mortality in the CHS cohort with both Medicare cohorts over a 10-year follow-up period. We obtained dates of death from the denominator files. To compare observed mortality rates, we included all beneficiaries from each cohort. To compare risk-adjusted rates, we only included beneficiaries from each cohort who had been continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare for the entire year prior to January 1, 1993.

Statistical Analysis

As mentioned previously, the second phase of CHS recruitment targeted African American beneficiaries. As a result, the demographic distribution of the CHS cohort on January 1, 1993, is not the same as the demographic distribution of the Medicare population. Because our intent was to validate the CHS cohort, we applied weights to all Medicare beneficiaries so that the age, sex, and race distributions in the Medicare population reflected those in the CHS cohort. For weighting, we truncated age at 98 years for both the CHS cohort and the Medicare population. We created weights for each combination of age group (by year, range 65 to 98), sex (male or female), and race (black, white, or other/unknown). Of the 204 possible weighting groups, 144 were represented in the CHS cohort. Medicare beneficiaries in an unrepresented group were assigned a weight of zero. Weights for beneficiaries in other groups were calculated by dividing the proportion of the CHS cohort in each age, sex, and race group by the proportion of the Medicare population in the same group. For example, 70-year-old white men represented 2.6% of the CHS cohort and 2.1% of the Medicare population. Therefore, we assigned a weight of approximately 1.3 to 70-year-old white men in the Medicare data.

We describe demographic and administrative characteristics, comorbid conditions, resource use and costs, and mortality for the CHS cohort and both the national and regional Medicare cohorts. We present continuous variables as either medians with interquartile ranges or means with standard deviations. We present categorical variables as frequencies with percentages. We used a Kaplan-Meier estimator to calculate all-cause mortality at 1 year, 5 years, and 10 years for each cohort. We tested for differences between the CHS cohort and each Medicare cohort using t tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. We used a Cox proportional hazards model to compare unadjusted and adjusted mortality over the 10-year period. The adjusted model controlled for demographic characteristics and for the previously identified comorbid conditions.

We used SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, North Carolina) for all analyses.

Results

There were 5,254 participants in the CHS cohort, 1,669,871 beneficiaries in the national Medicare cohort, and 10,075 beneficiaries in the regional Medicare cohort. Among persons enrolled continuously in fee-for-service Medicare in 1992, there were 4,604 participants in the CHS cohort (88% of the total cohort), 1,306,957 beneficiaries in the national Medicare cohort (78%), and 6,982 beneficiaries in the regional Medicare cohort (69%). Table 1 shows the demographic and administrative characteristics of the CHS cohort and the unweighted regional and national Medicare cohorts. The median age was 2 years greater in the CHS cohort than in either of the Medicare cohorts. The CHS cohort also had a higher proportion of men and African American participants and a much lower proportion of other races than the Medicare cohorts. After applying weights to the Medicare cohorts, the distributions of demographic characteristics were the same. All of the results that follow reflect calculations based on the weighted Medicare cohorts.

Table 1.

Demographic and Administrative Characteristics of the CHS Cohort and the Medicare Cohorts as of January 1, 1993

| Characteristic | CHS Cohort (n = 5,254) | Regional Medicare Cohort (n = 10,075) | P Valuea | National Medicare Cohort (n = 1,669,871) | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristicsc | |||||

| Age, median (interquartile range), y | 74 (71–79) | 72 (68–78) | < .001 | 72 (68–79) | < .001 |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 2,218 (42.2) | 3,973 (39.4) | < .001 | 677,135 (40.6) | .01 |

| Race, No. (%) | < .001 | < .001 | |||

| Black | 794 (15.1) | 926 (9.2) | 124,132 (7.4) | ||

| White | 4,418 (84.1) | 7,998 (79.4) | 1,430,514 (85.7) | ||

| Other/unknown | 42 (0.8) | 1,151 (11.4) | 115,225 (6.9) | ||

|

| |||||

| Administrative Characteristicsd | |||||

| Lacks Medicare Part B coverage | 134 (2.6) | 1,182 (5.3) | < .001 | 157,299 (3.6) | < .001 |

| Medicare plan enrollment, No. (%) | < .001 | < .001 | |||

| Fee-for-service | 4,804 (91.4) | 8,701 (85.3) | 1,557,158 (92.8) | ||

| Managed care organization | 450 (8.6) | 1,374 (14.7) | 112,713 (7.2) | ||

| End-stage renal disease | 8 (0.2) | 30 (0.4) | .01 | 5,217 (0.4) | .005 |

| Medicaid | 179 (3.4) | 1,175 (11.5) | < .001 | 153,105 (10.2) | < .001 |

| Disability was original reason for entitlement | 226 (4.3) | 646 (6.6) | < .001 | 106,956 (6.9) | < .001 |

Abbreviation: CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study.

P values for comparisons between the CHS cohort and the Medicare regional cohort.

P values for comparisons between the CHS cohort and the Medicare national cohort.

Values for all cohorts are expressed as unweighted number (unweighted percentage).

Values for the CHS cohort are expressed as unweighted number (unweighted percentage). Values for the Medicare cohorts are expressed as unweighted number (weighted percentage).

Compared to both Medicare cohorts, CHS participants were less likely to lack Medicare Part B coverage, to have a diagnosis of end-stage renal disease, to be concurrently enrolled in Medicaid, and to have been originally entitled to Medicare as a result of disability (Table 1). CHS participants were more likely to be enrolled in Medicare managed care than beneficiaries in the national Medicare cohort but were less likely to be enrolled in a Medicare managed care plan than the regional Medicare cohort. The only CHS region with appreciable Medicare managed care enrollment was Sacramento County, California. We found higher enrollment in Medicare managed care among CHS participants (32%) than among Medicare beneficiaries (22%; P < 0.001).

For beneficiaries continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare in 1992, Table 2 shows the percentage in each cohort with the listed comorbid conditions on any claim from 1992. Compared with the national Medicare cohort, CHS participants were significantly more likely to have had a prior myocardial infarction or to have been diagnosed with peripheral vascular disease, coronary heart disease, valvular heart disease, hypertension, or rheumatic disease. CHS participants were significantly less likely to have been diagnosed with congestive heart failure, stroke/transient ischemic attack, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, or diabetes mellitus. Among all of these differences, however, only the proportion of patients with peripheral vascular disease and coronary heart disease were different by more than two percentage points between cohorts.

Table 2.

Comorbid Conditions in the CHS Cohort and the Weighted Medicare Cohorts in the Calendar Year Before January 1, 1993a

| Comorbid Conditionb | CHS Cohort (n = 4,604) | Regional Medicare Cohort (n = 6,982) | P Valuec | National Medicare Cohort (n = 1,306,957) | P Valued |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 507 (11.0) | 670 (11.1) | .94 | 138,444 (11.3) | .48 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 431 (9.4) | 701 (10.7) | .02 | 124,054 (9.8) | .36 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 661 (14.4) | 1,087 (16.8) | < .001 | 205,720 (16.3) | < .001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 403 (8.8) | 702 (10.3) | .006 | 137,134 (10.6) | < .001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 1,253 (27.2) | 1,599 (24.1) | < .001 | 308,152 (24.1) | < .001 |

| Dementia | 77 (1.7) | 207 (2.9) | < .001 | 36,245 (2.5) | < .001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 644 (14.0) | 869 (13.6) | .56 | 183,541 (15.1) | .03 |

| Hypertension | 2,026 (44.0) | 2,803 (42.4) | .08 | 524,854 (42.2) | .02 |

| Myocardial infarction | 199 (4.3) | 273 (4.5) | .57 | 45,049 (3.6) | .005 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 165 (3.6) | 217 (3.2) | .19 | 40,218 (3.2) | .15 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 550 (12.0) | 808 (11.9) | .92 | 126,203 (9.8) | < .001 |

| Renal disease | 74 (1.6) | 113 (1.7) | .59 | 21,197 (1.8) | .33 |

| Rheumatic disease | 166 (3.6) | 229 (3.2) | .19 | 37,629 (3.0) | .009 |

| Stroke/transient ischemic attack | 301 (6.5) | 503 (7.6) | .02 | 93,253 (7.3) | .04 |

| Valvular heart disease | 309 (6.7) | 394 (6.2) | .24 | 69,422 (5.5) | < .001 |

Abbreviations: CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Restricted to patients continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare in 1992. Values for the CHS cohort are expressed as unweighted number (unweighted percentage). Values for the Medicare cohorts are expressed as unweighted number (weighted percentage).

Derived from International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes.

P values for comparisons between the CHS cohort and the regional Medicare cohort.

P values for comparisons between the CHS cohort and the national Medicare cohort.

Compared with the regional Medicare cohort, CHS participants were significantly more likely to have been diagnosed with coronary heart disease but less likely to have been diagnosed with congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, stroke/transient ischemic attack, dementia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Of these differences, only the proportion of patients with coronary heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease differed by more than two percentage points between cohorts.

Resource use and costs in each cohort in 1992 are shown in Table 3. For almost all measures reported, the magnitude of differences between cohorts was small. In 1992, the CHS cohort had slightly fewer inpatient stays per beneficiary compared with both Medicare cohorts. The CHS cohort had slightly more outpatient visits per beneficiary and slightly fewer medical evaluation and management visits than the regional Medicare cohort. The only resource use measure for which there was substantial variation was the mean number of cardiology evaluation and management visits. On average, CHS participants had about one additional visit as compared with beneficiaries in both of the Medicare cohorts. Measures of costs did not differ between the CHS cohort and both of the Medicare cohorts.

Table 3.

Resource Use and Costs to Medicare in the CHS and Weighted Medicare Cohorts in the Calendar Year Before January 1, 1993a

| Variable | CHS Cohort (n = 4,604) | Regional Medicare Cohort (n = 6,982) | P Valueb | National Medicare Cohort (n = 1,306,957) | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource use, mean (SD) | |||||

| Inpatient stays | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.8) | .002 | 0.3 (0.8) | < .001 |

| Outpatient visits | 1.9 (3.3) | 1.7 (4.1) | .002 | 2.0 (3.9) | .29 |

| Evaluation and management visits | 11.2 (10.2) | 11.7 (12.1) | .03 | 11.0 (11.8) | .19 |

| Cardiology evaluation and management visits | 1.4 (2.3) | 0.6 (1.5) | < .001 | 0.3 (1.1) | < .001 |

| Direct costs to Medicare, mean (SD), $ | |||||

| Total costs | 2,952 (7,401) | 3,118 (7,926) | .27 | 2,930 (7,634) | .85 |

| Inpatient costs | 1,632 (6,019) | 1,742 (6,214) | .36 | 1,636 (5,829) | .97 |

| Outpatient costs | 308 (811) | 299 (1,173) | .68 | 298 (1,811) | .61 |

| Physician costs | 1,012 (1,588) | 1,076 (1,808) | .06 | 995 (1,955) | .58 |

Abbreviations: CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study.

Restricted to patients continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare in 1992. Values for the Medicare cohorts are based on weighted data.

P values for comparisons between the CHS cohort and the Medicare regional cohort.

P values for comparisons between the CHS cohort and the Medicare national cohort.

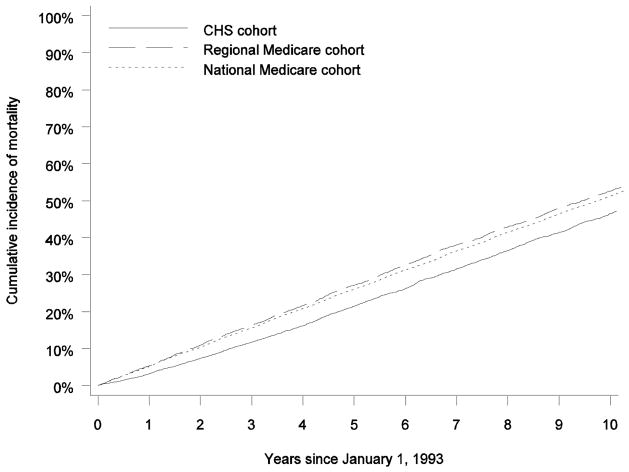

Figure 2 shows the mortality rate among all beneficiaries in each cohort. Over the 10-year period, the CHS cohort had markedly lower mortality than both of the Medicare cohorts. At 1 year, mortality in the CHS cohort was more than 40% lower (3.0% vs 5.3% for the regional Medicare cohort and 5.3% for the national Medicare cohort). At 5 years, mortality was approximately 25% lower (19.7% vs 26.5% for the regional Medicare cohort and 25.9% for the national Medicare cohort). At 10 years, mortality was approximately 15% lower (43.1% vs 51.0% for the regional Medicare cohort and 50.8% for the national Medicare cohort). Observed mortality in the CHS cohort was significantly different than observed mortality in both of the Medicare cohorts (P < 0.001). Observed mortality rates among beneficiaries who were continuously enrolled in Medicare fee-for-service in 1992 followed similar patterns (Table 4). The hazard ratios of mortality for beneficiaries in the national and regional Medicare cohorts, compared with patients in the CHS cohort, were 0.78 (95% confidence interval, 0.75–0.82) and 0.74 (95% confidence interval, 0.70–0.78), respectively. After adjustment for demographic characteristics and comorbid conditions, these hazard ratios were nearly unchanged.

Figure 2.

Mortality at 10 Years in the CHS Cohort, the Regional Medicare Cohort, and the National Medicare Cohort

Table 4.

Observed Mortality and Hazard Ratios of Mortality During 10-Year Follow-up in the CHS and Weighted Medicare Cohortsa

| Variable | CHS Cohort (n = 4,604) | Regional Medicare Cohort (n = 6,982) | National Medicare Cohort (n = 1,306,957) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observed mortality b | |||

| 1-year | 136 (3.0) | 430 (5.9) | 72,278 (5.4) |

| 5-year | 928 (20.2) | 1,916 (27.9) | 343,657 (26.4) |

| 10-year | 2,007 (43.6) | 3,544 (53.2) | 653,315 (51.4) |

| Hazard ratio of mortality (95% CI) | |||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 [Reference] | 0.74 (0.70–0.78) | 0.78 (0.75–0.82) |

| Adjusted | 1.00 [Reference] | 0.74 (0.70–0.78) | 0.77 (0.74–0.81) |

Abbreviations: CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; CI, confidence interval.

Restricted to patients continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare in 1992.

Values for the CHS cohort are expressed as unweighted number of events (unweighted rate/100). Values for the Medicare cohorts are expressed as unweighted number of events (weighted rate/100).

Conclusions

This study compared the CHS cohort to national and regional cohorts of Medicare beneficiaries to assess the external validity of the CHS. Compared with both Medicare cohorts, the CHS cohort was older and had more men and African American participants. After weighting the Medicare cohorts so that the demographic distributions were identical to the CHS cohort, differences remained in administrative characteristics, comorbid conditions, resource use, and mortality. In general, the CHS cohort was healthier, less likely to be concurrently enrolled in Medicaid, and more likely to be enrolled in Medicare managed care. The CHS cohort also had lower mortality than both Medicare cohorts, and this disparity persisted during the 10-year follow-up period. The lower mortality rate in the CHS cohort persisted after risk adjustment.

Given the CHS recruitment strategy, the study protocol, and the potential for volunteer bias, the differences we observed are not unexpected. The CHS recruited noninstitutionalized, community-dwelling, Medicare-eligible individuals who were aged 65 or older as of 1989, the first year of CHS recruitment. There are several ways in which this recruitment strategy may be reflected in the differences we observed. First, the difference in age was expected because the recruitment strategy yielded a cohort in which the majority of CHS participants were aged 69 or older as of January 1, 1993. In comparison, both Medicare cohorts included beneficiaries who were aged 65 or older.

Second, the difference in Medicare managed care enrollment may reflect the recruitment of participants from Sacramento County, California. In the early 1990s, California was a leader in the penetration of Medicare-sponsored managed care plans.22 For example, in 1993, California alone accounted for 40% of all Medicare managed care enrollees in the United States, and almost 20% of California’s total Medicare population was enrolled in Medicare managed care.22

Third, the finding that CHS participants were less likely to be diagnosed with dementia or stroke/transient ischemic attack may reflect the exclusion of persons who were unable to provide informed consent or communicate verbally during the baseline interview. The finding that CHS participants were less likely to be diagnosed with congestive heart failure may be due to underrepresentation of this diagnosis in the CHS, since congestive heart failure is common among persons living in nursing homes (who were excluded in the CHS). Likewise, the lower mortality rate among CHS participants may reflect the exclusion of persons who were undergoing treatment for cancer, were confined to a wheelchair, or were in a hospice program. The exclusion of institutionalized persons in the CHS cohort may also explain this finding; however, the rate of institutionalized persons over age 65 in the United States is generally low and thus would not completely account for the consistently lower mortality rate in the CHS cohort during the 10-year follow-up period.24

Fourth, another explanation for the lower mortality rate may be the proportion of participants enrolled in the CHS who were married (57.1% of women and 84.8% of men), which reflects higher marriage rates than among the general elderly population.25 Although the majority of participants in the CHS were recruited from a randomly sampled Medicare eligibility list, 30% of participants were recruited from households of sampled participants, of whom more than 75% were spouses.12 Marriage can be an important source of social support and has been shown to be associated with improved health status.26,27 Several studies have shown that persons who are married have a lower risk of mortality than those who are not married, even after adjustment for other factors.27,28

The finding that CHS participants had more cardiology evaluation and management visits per year may reflect the study protocol, which required participants to receive annual clinic examinations, particularly since there were few differences in mean physician costs per patient in the CHS cohort as compared with the Medicare cohorts. Specifically, CHS participants were referred from the annual clinic exam to a cardiologist if there was evidence of asymptomatic cardiovascular disease, “such as unstable angina, worsening congestive heart failure, uncontrolled hypertension…, or new onset transient ischemic attacks.”11

Lastly, volunteer bias (ie, those who volunteer may differ in certain ways from those who do not29) may also provide an explanation for the lower mortality rate among CHS participants and some of the differences in comorbid conditions we observed. This may be particularly true in the comparison between the CHS cohort and the regional Medicare cohort, since this was the population from which CHS participants were originally sampled.

This study has some limitations. First, Medicare provides claims data for beneficiaries enrolled in fee-for-service care, not managed care.30 Thus, we were unable to compare comorbid conditions and resource use for persons enrolled in managed care. Second, we cannot infer whether a beneficiary was institutionalized based on Medicare claims. As a result, we were unable to make a direct comparison between the noninstitutionalized CHS cohort and noninstitutionalized beneficiaries in the Medicare cohorts. However, a primary strength of this study is that it allowed for direct comparisons of the CHS cohort with the population from which it was initially drawn on both a national level and within the specific geographic regions sampled by the CHS. Furthermore, Medicare data provide a nationally representative sample of all patients aged 65 or older, and because Medicare data use standard individual identifiers, we were able to match the CHS cohort with Medicare claims.

A final limitation is that we were not able to compare the entire initial CHS cohort with the Medicare population, because earlier Medicare claims data were not available. However, of the 5,553 CHS participants alive at the 1992–1993 follow-up exam, 5,254 (95%) could be matched to the Medicare denominator file and were used in this analysis.

The CHS is national resource of information without which data on risk factors for cardiovascular disease and stroke in the elderly population would be limited. In this analysis, we examined the external validity of the CHS to determine whether it is representative of Medicare beneficiaries nationally and of Medicare beneficiaries residing in the geographic regions sampled by the CHS. We found that the CHS cohort was comparable to the national and regional cohorts from which it was sampled with regard to comorbid conditions and resource use, but had lower mortality. These findings suggest that it may not be appropriate to project absolute rates of disease and outcomes based on CHS data to the entire Medicare population. However, there is no reason to expect that the relative risks of cardiovascular disease and events associated with physiologic processes identified in the CHS data would differ for nonparticipants.

Acknowledgments

Supported by contracts N01HC85079 through N01HC85086, N01HC35129, N01HC15103, N01HC55222, N01HC75150, and N01HC45133 and grant U01HL080295 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.chs-nhlbi.org/pi.htm.

Footnotes

Complete Author Information

Lisa D. DiMartino, MPH, Duke Clinical Research Institute, PO Box 17969, Durham, NC 27715; telephone: 919-668-8101; fax: 919-668-7124; e-mail: lisa.dimartino@duke.edu.

Bradley G. Hammill, MS, Duke Clinical Research Institute, PO Box 17969, Durham, NC 27715; telephone: 919-668-8101; fax: 919-668-7124; e-mail: brad.hammill@duke.edu.

Lesley H. Curtis, PhD, Duke Clinical Research Institute, PO Box 17969, Durham, NC 27715; telephone: 919-668-8101; fax: 919-668-7124; e-mail: lesley.curtis@duke.edu.

John S. Gottdiener, MD, Division of Cardiology, University of Maryland Medical Center, Room G3K18, Baltimore, MD 21201; telephone: 410-328-6190; fax: 410-328-3530; e-mail: jgottdie@medicine.umaryland.edu.

Teri A. Manolio, MD, PhD, National Human Genome Research Institute, 31 Center Dr, Room 4B-09, Bethesda, MD 20892-2154; telephone: 301-402-2915; fax: 301-402-4831; e-mail: manolio@nih.gov.

Neil R. Powe, MD, MPH, MBA, Welch Center for Prevention, Epidemiology and Clinical Research, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, 2024 E. Monument St, Suite 2-600, Baltimore, MD 21205; telephone: 410-955-6953; fax: 410-955-0476; e-mail: npowe@jhmi.edu.

Kevin A. Schulman, MD, Duke Clinical Research Institute, PO Box 17969, Durham, NC 27715; telephone: 919-668-8101; fax: 919-668-7124; e-mail: kevin.schulman@duke.edu.

References

- 1.Mausner JS, Kramer S. Epidemiology: An Introductory Text. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) [Accessed June 3, 2008]; Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT00005133.

- 3.Lange LA, Carlson CS, Hindorff LA, et al. Association of polymorphisms in the CRP gene with circulating C-reactive protein levels and cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2006;296:2703–2711. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.22.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappola AR, Fried LP, Arnold AM, et al. Thyroid status, cardiovascular risk, and mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2006;295:1033–1041. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shlipak MG, Sarnak MJ, Katz R, et al. Cystatin C and the risk of death and cardiovascular events among elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2049–2060. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ariyo AA, Thach C, Tracy R Cardiovascular Health Study Investigators. Lp(a) lipoprotein, vascular disease, and mortality in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2108–2115. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shlipak MG, Fried LF, Cushman M, et al. Cardiovascular mortality risk in chronic kidney disease: comparison of traditional and novel risk factors. JAMA. 2005;293:1737–1745. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.14.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, et al. Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:14–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Psaty BM, Furberg CD, Kuller LH, et al. Isolated systolic hypertension and subclinical cardiovascular-disease in the elderly—initial findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA. 1992;268:1287–1291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fried LP, Kronmal RA, Newman AB, et al. Risk factors for 5-Year mortality in older adults—the Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA. 1998;279:585–592. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.8.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tell GS, Fried LP, Hermanson B, et al. Recruitment of adults 65 years and older as participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1993;3:358–366. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Cardiovascular Health Study. [Accessed April 29, 2008];Baseline Monograph: Description of Study and of Collected Data—Draft 3. 1998 November 12; Available at: http://www.chs-nhlbi.org/monograf/mono98.htm.

- 14. [Accessed April 29, 2008];The Cardiovascular Health Study: Overview of CHS Design. Available at: http://www.chs-nhlbi.org/CHSOverview.htm.

- 15.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed September 10, 2008];Medicare: A Primer. 2007 March; Available at: http://kff.org/medicare/upload/7615.pdf.

- 16.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed September 10, 2008];Medicaid: A Primer. 2007 March; Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/Medicaid-A-Primer-pdf.

- 17.Asper F, Merriman K. Differences in How the Medicare 5% Files Are Generated. [Accessed April 29, 2008];Research Data Assistance Center. 2007 ResDAC Publication No. TN-011. Available at: http://www.resdac.umn.edu/Tools/TBs/TN-011.asp.

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed September 10, 2008];International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/otheract/icd9/abticd9.htm.

- 19.Birman-Deych E, Waterman AD, Yan Y, et al. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM codes for identifying cardiovascular and stroke risk factors. Med Care. 2005;43:480–485. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160417.39497.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. [Accessed September 10, 2008];Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, HCPCS General Information Overview. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/medhcpcsgeninfo/01_overview.asp.

- 22.McMillan A. Trends in Medicare health maintenance organization enrollment: 1986–93. Health Care Financ Rev. 1993;15:135–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmed A, Weaver MT, Allman RM, et al. Quality of care of nursing home residents hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1831–1836. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson GF, Hussey PS. Population aging: a comparison among industrialized countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2000;19:191–203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bureau of the Census, US Department of Commerce. Sixty-Five Plus in the United States. Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census; 1995. [Accessed April 29, 2008]. Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/statbriefs/agebrief.html. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sultan S, Fisher DA, Voils CI, et al. Impact of functional support on health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2004;101:2737–2743. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson NJ, Backlund E, Sorlie PD, et al. Marital status and mortality: the national longitudinal mortality study. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:224–238. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(99)00052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan RM, Kronick RG. Marital status and longevity in the United States population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:760–765. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.037606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benfante R, Reed D, MacLean C, et al. Response bias in the Honolulu Heart Program. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;130:1088–1100. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, et al. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40:IV–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Virnig BA, McBean M. Administrative data for public health surveillance and planning. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:213–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]