Abstract

The review of requests for a positive opinion of the ethics committees (application procedure) as a requirement to start a clinical trial in Germany has been completely redesigned with the transposition of EU Directive 2001/20/EC in the 12th Amendment of the German Medicines Act in August 2004. The experience of applicants (sponsors, legal representatives of sponsors in the EU and persons or organizations authorized by the sponsors to make the application, respectively) in terms of interactions with the ethics committees in Germany has been positive overall, especially with respect to ethics committee adherence to the statutory timelines applicable for review of requests. However, inconsistencies between ethics committees exist in terms of the form and content of the requirements for application documents and their evaluation.

With the objective of further improving both the quality of applications and the evaluation of those applications by ethics committees, a survey among members of the German Association of Research-Based Pharmaceutical Companies (VFA) was conducted from January to April 2008. Based on reasoned opinions issued by the respective ethics committee in charge of the coordinating principal investigator (coordinating ethics committee), the type and frequency of formal and content-related objections to applications according to § 7 of the German Good Clinical Practice (GCP) Regulation were systematically documented, and qualitative and quantitative analyses performed. 21 out of 44 members of the VFA participated in the survey. 288 applications for Phase I–IV studies submitted between January and December 2007 to 40 ethics committees were evaluated.

This survey shows that about one in six applications is incomplete and has formal and/or content objections, respectively, especially those that pertain to documents demonstrating the qualification of the investigator and/or suitability of the facilities. These objections are attributable to some extent to the differing and/or unclear requirements of the individual ethics committees on the content and comprehension of the submission documents. However, applicants also need to pay more attention to the completeness and validity of the submission documents. The majority of content-related objections apply to the patient information and consent documents and study protocols submitted. Applicants on average acted upon only 3 out of 4 objections, for various reasons: the relevant information was already given in the submitted documents, but had not been taken into consideration by the ethics committees; objections were not applicable; objections lacked a legal basis. In such cases the applicants made reference to the specific information already submitted or gave reasons for not acting on the objection. This course of action was accepted by the ethics committees, with few exceptions. The survey sheds light on the existing inconsistencies in the evaluations of applications by the various ethics committees and suggests ways in which the existing constructive dialogue between applicants and ethics committees may provide a basis to further harmonize both the requirements regarding form and content of application documents, and the criteria for evaluation of applications by ethics committees within the legal framework.

Keywords: ethics committees, application procedure, formal and content-related objections, clinical trials

Abstract

Das Verfahren bei der Ethik-Kommission (EK) als Voraussetzung für den Beginn einer klinischen Prüfung, wurde in Deutschland im August 2004 mit der Umsetzung der EU-Richtlinie 2001/20/EG in der 12. AMG-Novelle grundlegend neu geregelt. Die bisherigen Erfahrungen von Antragstellern (Sponsoren, gesetzliche Vertreter von Sponsoren in der EG bzw. Personen oder Organisationen, die von den Sponsoren zur Antragstellung bevollmächtigt sind) in der Zusammenarbeit mit den Ethik-Kommissionen sind im Allgemeinen positiv, besonders was die Einhaltung der Fristen bei der Antragsbearbeitung durch die Ethik-Kommissionen betrifft. Inkonsistenzen existieren allerdings in den formalen und inhaltlichen Anforderungen an die eingereichten Antragsunterlagen und deren Bewertung durch die verschiedenen Ethik-Kommissionen.

Mit dem Ziel einer weiteren Qualitätssteigerung der Antragstellung sowie der Bewertung durch die Ethik-Kommissionen, wurden mittels einer von Januar bis April 2008 durchgeführten Umfrage bei Mitgliedsunternehmen des Verbandes Forschender Arzneimittelhersteller e.V. (VFA) systematisch Art und Häufigkeit von formalen und inhaltlichen Einwänden erfasst sowie qualitativ und quantitativ ausgewertet. Grundlage waren Bescheide der für den Leiter der klinischen Prüfung jeweils zuständigen Ethik-Kommission (federführende Ethik-Kommission) bei Erstantragstellung einer klinischen Prüfung gemäß § 7 GCP-V.

21 der 44 Mitgliedsunternehmen des VFA haben sich an der Umfrage beteiligt. Ausgewertet wurden 288 Antragsverfahren auf zustimmende Bewertung einer klinischen Prüfung der Phasen I bis IV, die im Zeitraum Januar bis Dezember 2007 bei 40 Ethik-Kommissionen gestellt wurden.

In der vorliegenden Umfrage ist etwa jeder sechste Antrag unvollständig bzw. weist formale und/oder inhaltliche Einwände zu den Antragsunterlagen, insbesondere bezüglich der Dokumentation der Prüferqualifikation und/oder Eignung der Prüfstelle auf. Diese Einwände sind zum Teil auf die unterschiedlichen und/oder unklaren Anforderungen der einzelnen Ethik-Kommissionen hinsichtlich Inhalt und Umfang der Antragsunterlagen zurückzuführen. Aber auch von Seiten der Antragsteller ist verstärkt auf die Vollständigkeit und erforderliche Aussagekraft der Antragsunterlagen zu achten. Die meisten inhaltlichen Einwände bezogen sich auf die vorgelegten Patienteninformationen und Einwilligungserklärungen sowie die Prüfpläne. Insgesamt betrachtet, sind die Antragsteller allerdings im Durchschnitt nur 3 von 4 Einwänden nachgekommen, da die von den Ethik-Kommissionen angeforderten Informationen mit den eingereichten Unterlagen bereits vorlagen, aber bei der Bewertung durch die Ethik-Kommissionen nicht berücksichtigt wurden, eine Vielzahl der Einwände nicht gerechtfertigt war oder die gesetzlichen Voraussetzungen für die Einwände fehlten. In diesen Fällen verwiesen die Antragsteller auf die vorgelegten Unterlagen oder begründeten durch nähere Erläuterungen und Stellungnahmen die Nicht-Umsetzung der Einwände. Dies wurde bis auf wenige Ausnahmen von den Ethik-Kommissionen akzeptiert. Die Umfrage beleuchtet die bestehende Heterogenität in den Bewertungen durch die verschiedenen Ethik-Kommissionen und zeigt Möglichkeiten auf, wie der bestehende konstruktive Dialog zwischen Antragsteller und Ethik-Kommissionen dazu dienen kann, die formalen und inhaltlichen Anforderungen an die einzureichenden Unterlagen sowie die Kriterien im Bewertungsverfahren klinischer Prüfungen bei den Ethik-Kommissionen innerhalb der gesetzlichen Rahmenbedingungen weiter zu harmonisieren.

Introduction

The 12th Amendment of the German Medicines Act (AMG) [1] implemented Council Directive 2001/20/EC [2] in national law in Germany in August 2004. Further resultant changes and requirements of the later Council Directive 2005/28/EC [3] were transposed to German law in the German GCP Regulation (GCP R) [4].

Implementation of the directives has brought about many fundamental legal changes in the processing and conduct of clinical trials in Germany. These include authorization of a clinical trial by the competent regulatory authority (German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) or Paul Ehrlich Institute (PEI)) and a positive opinion from the competent ethics committee (coordinating ethics committee) as criteria for clinical trial initiation. The general and particular requirements for a clinical trial and the procedures concerning the regulatory authority and ethics committees in Germany are set forth in German Medicines Act (AMG) §§ 40 to 42. The documents to be submitted to the competent regulatory authority and ethics committees, and the procedure and time limits for ethics committee review are specified in greater detail in GCP R § 7 and § 8. The documents to be submitted to the competent regulatory authority and ethics committees are not identical. For instance, the ethics committees additionally requires specific documents on the suitability of the investigational site and qualifications of the investigator, as well as submission of a patient informed consent document.

Recent experience and insights of applicants with ethics committee review of clinical trials are presented in the following. The analysis looks at form and content-related objections of coordinating ethics committees in their response to requests for a positive opinion. The conclusions reached are intended as a basis for improving the quality of applications and to facilitate further harmonization of the review process by ethics committees.

Methods

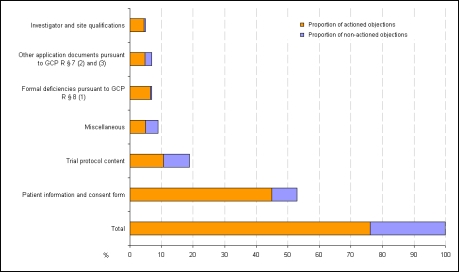

A VFA Clinical Research/Quality Assurance Subcommittee working party designed a survey (Attachment 2, Attachment 2) intended to investigate the type and frequency of formal and content-related objections in the decisions of coordinating ethics committees after first application for a clinical trial pursuant to GCP R § 7 (1–3). The survey questions asked for the number of first applications in the period from January to December 2007, the clinical trial phase, therapeutic indication, and respective coordinating ethics committee. Other questions asked for information on the number of formal and content-related objections per study application along with a brief description of the case in question, the subjective evaluation and the applicant’s response to the objections, and the ethics committee’s decision in each case. The respondent companies also classified the objections into 6 pre-specified evaluation categories. These were: Formal deficiencies pursuant to GCP R § 8 (1) as well as 5 categories of content-related objections regarding patient information and consent document, trial protocol content, investigator and site qualifications, other application documents pursuant to GCP R § 7 (2) and (3), and requests, remarks and recommendations not directly related to the application documents submitted pursuant to GCP R § 7 (2) and (3), called “miscellaneous” here (see Figure 1 (Fig. 1)).

Figure 1. Breakdown of formal and content-related objections as a percentage of total objections (Phase I to IV).

Survey

The survey was performed from January to April 2008 among VFA member companies and was in relation to first applications dating from January to December 2007. Of the 44 companies organized in the VFA and included in the survey, 22 companies are re¬presented on the VFA Clinical Research/Quality Assurance Subcommittee. 21 of those 22 took part in the survey. Survey evaluation was based on the above-described particulars on 288 applications of those 21 companies at 40 ethics committees. These account for about 21% of the 1400 applications for authorization of commercial and non-commercial clinical trials submitted to the regulatory authorities in 2007 [5], [6].

Results

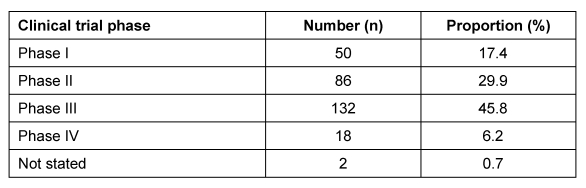

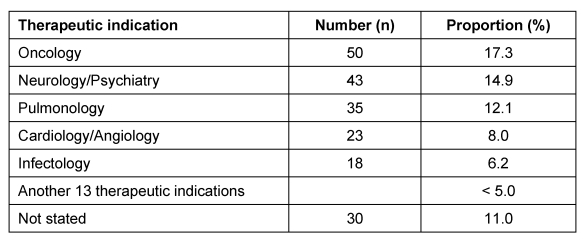

A breakdown by clinical trial phase and therapeutic indication for the 288 evaluated applications is given in Table 1 (Tab. 1) and Table 2 (Tab. 2).

Table 1. Breakdown of evaluated applications by clinical phase I–IV.

Table 2. Breakdown of evaluated applications by therapeutic indication.

Frequency of formal and content-related objections in relation to total objections

53% of the total 1299 ethics committee objections reported were in reference to the patient information and consent document, followed by 19% objections related to the submitted trial protocol (Figure 1 (Fig. 1)). 7% of total objections were due to formal deficiencies pursuant to GCP R § 8 (1) and 7% were due to formal deficiencies in other application documents pursuant to GCP R § 7 (2) and (3). Only 5% of total objections were in relation to specific documents on the site or investigators. 9% of objections came under the categories of requests, remarks and recommendations not directly related to the application documents submitted pursuant to § 7 (2) and (3) (called “miscellaneous” here). The distribution pattern for review by the ethics committees of state medical boards and university hospitals is virtually identical.

It is interesting to note that applicants did not act on 24% of objections: either because the relevant information was already given in the submitted documents, but had not been taken into consideration by the ethics committees, or because the objections lacked a legal basis. In such cases, the applicants made reference to the submitted documents or provided detailed explanations for not acting on the objections. Ethics committees accepted this, with 5 exceptions. The proportion of non-actioned objections was highest in the categories of „Trial protocol content“ (44%), „Other documents pursuant to GCP R § 7 (2) and (3)” (33%), and “Miscellaneous” (46%). Applicants acted on the majority of objections in the categories “investigator and site qualifications” and “patient information and consent document”, with actioning rates of 87% and 85%, respectively.

Frequency of formal and content-related objections in relation to study applications

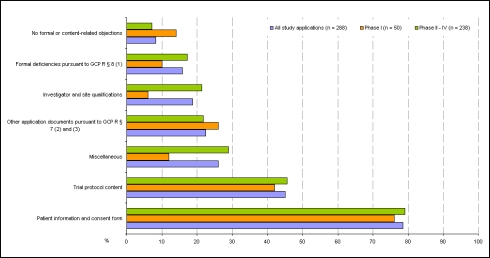

A look at study applications in terms of formal and content-related objections (cf. Figure 2 (Fig. 2)) shows that 78.5% of all study applications (76% Phase I; 79% Phase II–IV) received at least one objection relating to the submitted patient information and consent document, and 45.1% of all study applications (42% Phase I; 45.8% Phase II–IV) received at least one objection in terms of trial protocol content. The proportion of incomplete applications with formal objections was 16% in this survey (10% Phase I and 17.2% Phase II–IV). 24 out of the 288 study applications (total 8.3%; 14% of Phase I and 7.1% of Phase II–IV studies) had neither formal nor content-related objections, while 3 study applications were rejected on grounds of study design. The 10-day time limit for formal ethics committee review was missed only in the case of a single application. The ethics committee exceeded the 60-day processing time for content-based review for a total of 8 applications (2.8%).

Figure 2. Study applications with formal and content-related objections in percent (Phase I to IV).

Breakdown of study applications and breakdown of frequency of formal and content-related objections in relation to the ethics committees involved in the survey

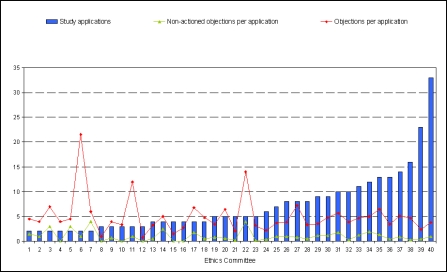

54.9% of the 288 study applications were submitted to 14 state/medical board ethics committees. 45.1% were submitted to 26 university hospital ethics committees. Only 10 (25%) of the total of 40 ethics committees involved in this survey each reviewed at least 10 applications, amounting to a total of 155 applications and hence accounting for more than half (53.8%) of all study applications.

Figure 3 (Fig. 3) shows the number of study applications per ethics committee.

Figure 3. Number of study applications and number of objections per application; breakdown among the 40 ethics committees involved in the survey.

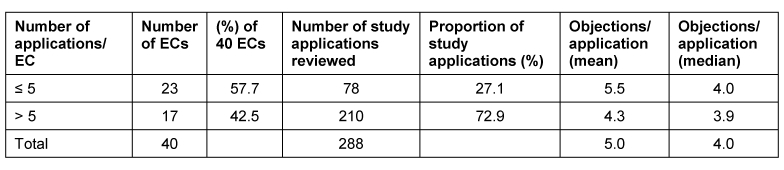

Stratification into two groups of all the ethics committees involved in this survey by the number of applications reviewed by each (cf. Table 3 (Tab. 3)) shows that 23 ethics committees (57.5%) each reviewed only up to 5 study applications (total 78), i.e. 27.1% of all study applications. These ethics committees on average raised more objections per application than the committees in the ethics committee group that each reviewed more than 5 applications. The latter ethics committees were much more homogeneous overall in their review of study applications. This ethics committee group represents 42.5% of the 40 involved ethics committees and reviewed 72.9% of the total 288 study applications.

Table 3. Number of study applications and number of objections per application; breakdown into 2 groups of ethics committees involved in the survey.

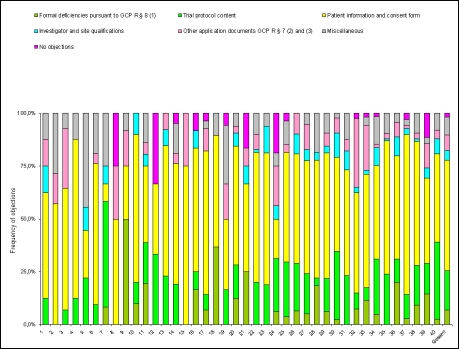

The frequency distribution of the objections matched to the respective review categories (trial protocol content, investigator and site qualifications etc.) shows a very heterogeneous picture between the ethics committees (Figure 4 (Fig. 4)).

Figure 4. Frequency of objections in percent; breakdown among the 40 ethics committees involved in the survey.

Type of formal and content-related objections

Pursuant to GCP R § 8, content-related review by an ethics committee begins only after the application has been deemed in order. If there are formal deficiencies, i.e. missing or incomplete documents pursuant to GCP R § 7 (2) and (3), the applicant has 14 calendar days in which to address those deficiencies. The 30-day (for mono-centre clinical trials) and 60-day time limit (for multi-centre clinical trials) for content-related review of the study application begins only after receipt of an application deemed to be in order. Incomplete applications defer the review phase and prolong the overall procedure.

The formal and content-related objections are listed in the following in descending order of frequency.

Formal objections

These are the most common formal deficiencies pursuant to GCP R § 8 (1):

Missing or incomplete information on the qualifications of investigators/and or site suitability, e.g. missing proofs of qualifications (CVs, GCP knowledge), inadequate description of patient recruitment process, and incomplete representations of investigative site capacity

Missing statement on inclusion of any persons dependent upon the sponsor or investigator pursuant to GCP R § 7 (3) (4)

Missing statement on compliance with data protection pursuant to GCP R § 7 (3) (15)

Missing or inadequate proof of insurance pursuant to GCP R § 7 (3) (13)

Content-related objections

In keeping with the outcome of the survey, by far the most common content-related objections concern the submitted patient information and consent documents. Typical objections:

Present patient information in language accessible to laypersons and explain jargon

Present patient information with contact details and address of investigator/site, e.g. in the form of letterhead

Present more clearly or add information on risks, adverse effects or side effects stating the percent frequency, based on the investigator brochure or package leaflet

Provide more specific details about the pseudonymization process in the data protection section

Point out in the insurance cover section that the insurance terms are to be handed out to patients, and state clearly what the patient should do in the event of a possible injury/claim or emergency

Clearly and precisely state the allowed birth control methods

State that the primary care physician is to be informed of the patient’s study participation with the patient’s consent

Other content-related objections concerned the submitted trial protocol. The respondent companies cited the following items as being the most common requests in connection with trial protocol content:

More extensive presentation of inclusion/exclusion or discontinuation criteria (e.g. that the trial does not recruit subjects committed to an institution by official or court order, or that the patient’s ability to give consent is a criterion for study participation; specify discontinuation criteria for the individual subject and for the entire clinical trial)

More precise particulars about contraception

Justify the study design, placebo arm in particular

Include publication policy, SAE report address and monitoring details

Objections relating to investigator qualifications and site suitability were reported as follows:

Investigator qualifications:

Inadequate proof of existing GCP knowledge; mention of the need for an AMG/GCP course. In some cases, proofs of other skills are requested, e.g. ECG Proficiency Certificate.

Information missing on other investigators involved in the study.

In one case, several sites were rejected by an ethics committee on the grounds of lack of investigator qualifications, but the ethics committee did not specify which particular qualifications were lacking.

Site suitability:

Requests for hospital director or head of department’s consent to study conduct.

Missing information on parallel and/or rival studies and any measures to ensure recruitment.

Typical objections concerning application documents pursuant to GCP R § 7 (2) and (3) were:

Provide more details of the publication clause in the sponsor-site agreement (§ 7 (3) (16)

Request for study-specific insurance certificate despite the presentation of proof of insurance pursuant to AMG § 40 (§ 7 (3) 13))

Provide a more detailed breakdown of investigator remuneration alongside the medical services performed (§ 7 (3) (14))

A large number of requests, remarks and recommendations not directly related to the application documents to be submitted pursuant to § 7 (2) and (3) were summarized in the Other objections category. The most common were:

Recommendation (or demand, in some cases) to take out accident en-route insurance

Demand for explanation or amendment of publication strategy

Demand for sponsor confirmation that every investigator was informed of pharmacology/toxicology results by a scientist responsible for pharmacology/toxicology testing and the risks likely associated with the clinical trial (cf. § 40 (1) (7))

Discussion

The procedure for evaluation of clinical trials by ethics committees changed radically in August 2004 with the implementation in Germany of European Directive 2001/20/EC through the 12th Amendment of the German Medicines Act and the associated implementing regulations. The objective was further improvement of patient safety and clinical trial quality and harmonization of regulatory requirements in the EU. EU harmonization of application procedures in particular has made things easier for applicants, despite the significantly higher requirements in terms of the amount of application documents required. Hence, national or indeed local special regulations should be viewed with criticism on a fundamental level.

From the point of view of the pharmaceutical companies represented in the VFA, the new procedure is fundamentally positive, for example the reduction to a single ethics committee opinion and the introduction of time limits. This can be clearly seen from the present survey among a broad and eminently representative database.

However, the survey also shows that there is room for improvement in many respects. For instance, 16% to 23% of applications had formal deficiencies (GCP R § 8 (1)) and gave rise to formal and/or content-related objections with respect to the application documents (§ 7 (2) and (3)). These are partly due to different and/or unclear requirements of individual ethics committees in terms of content and extent of application documents. Nevertheless, applicants too should pay more attention to completeness and meaningfulness of application documents, in particular with respect to documentation of investigator qualifications and site suitability. If one considers that the basis of this survey is the decision of the respective ethics committee in charge of the coordinating principal investigator (coordinating ethics committee), and the ethics committees competent for other investigators (involved ethics committees) generally address objections and queries regarding investigator qualifications and site suitability straight to the applicant, the actual proportion is likely to be even higher. As far as this aspect is concerned, a legal clarification of the definition of investigator and of the requirements for application documents would contribute significantly toward further improvement of efficiency and acceleration of the review process.

The major heterogeneity in the evaluation procedures between the different ethics committees has become very clear in this survey. There are major differences in some cases in terms of requirements for content and length of patient information and consent documents. While some ethics committees insist upon the use of their own data protection statement or formulations concerning insurance cover, other ethics committees refer applications to the template drafted by the Working Party of Medical Ethics Committees in Germany. There are also major discrepancies in the approaches of different ethics committees as regards inclusion and exclusion criteria. Some ethics committees encourage applicants to omit a list of inclusion and exclusion criteria entirely; other ethics committees say the listing should be limited to the most important criteria. Harmonization should be sought intensively, in order to make the procedure more calculable and even quicker. Applicants are particularly keen to see the establishment and general acceptance of binding standards, e.g. the templates drafted by the German Medical Ethics Committee Working Party.

The high proportion of non-actioned objections revealed in the survey is attributable to the fact that some objections lacked any legal basis; that the information requested by ethics committee was already available in the submitted documents, trial protocol in particular, but had not been taken into account by the ethics committee in its review; and that a large number of objections were untenable. This proportion should be reduced significantly since it takes up resources both on the part of the applicant and on the part of the ethics committees with no associated benefits for patient safety or clinical trial quality.

To ensure that clinical trials can continue to be performed in Germany in future, it is important to check closely whether ethics committee demands for further specification of inclusion and exclusion criteria or discontinuation criteria for individual subjects, for example in the form of a trial protocol amendment, are really necessary from an ethical point of view. In large multinational clinical trials, for instance, amendments of the kind are, firstly, virtually impossible to implement; and, secondly, national particularities can generally be implemented by other means.

The overall conclusion is that more professionalization of the ethics committee review procedure has had a positive impact on the quality and duration of review. Ethics committees which process a large number of applications as coordinating ethics committees and so have a very well developed infrastructure and abundant experience issue fewer objections overall. This observation applies in particular to objections relating to the trial protocol. It is noteworthy that only 25% of the 40 ethics committees involved in this survey evaluated more than half (53.8%) of the total number of clinical trial applications. This situation is essentially being determined by the applicants which constitute the coordinating ethics committee with their selection of the coordinating principal investigator.

Conclusions

Our survey shows

Major heterogeneity in terms of requirements and evaluations, in particular with respect to patient information and consent document and investigator qualifications. From the applicants’ point of view, the requirements seem to be subjective in many cases rather than based on definite legal specifications

That constructive solutions are found in most cases of dissent between applicant and ethics committees which enable both the implementation and justified non-implementation of action on the objections in question

That the positive approach initiated by the Working Party of Medical Ethics Committees in Germany toward formal standardization of application in terms of uniform requirements on the extent of documents to be submitted and uniform and binding review criteria based on strict compliance with legal requirements, e.g. via templates, should be continued in a systematic fashion

That the next amendment of the AMG and GCP Regulation must involve clarification and simplification of the requirements and application documents necessary for the conduct of clinical trials.

The survey presented here on the experiences of the pharmaceutical companies represented in the VFA with respect to clinical trial review procedures by ethics committees identifies effective ways toward further optimization of the quality and efficiency of this procedure, with the aim both of protecting patients’ interests and strengthening Germany’s position as an attractive research location. It is necessary to continue the initiated constructive and common dialogue between applicants, ethics committees and regulatory authorities in order to achieve further progress toward those ends.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

The authors are employees of VFA member companies.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the VFA member companies that participated in the survey, and Dr. F. Hundt and Dr. T. Ruppert for critical review of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Gesetz über den Verkehr mit Arzneimitteln (Arzneimittel - AMG). Arzneimittelgesetz in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 12. Dezember 2005 (BGBl. I S. 3394), das zuletzt durch Artikel 9 Abs. 1 des Gesetzes vom 23. November 2007 (BGBl. I S. 2631) geändert worden ist [German Drug Law/German Medicines Act] Berlin: Bundesministerium der Justiz; [cited 2009 Jul 07]. Available from: http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/amg_1976/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Directive 2001/20/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 April 2001 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States relating to the implementation of good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products for human use. Official Journal of the European Union. 2001;L 121, 1/5/2001:34–44. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/pharmaceuticals/eudralex/vol-1/dir_2001_20/dir_2001_20_en.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Commission. Commission Directive 2005/28/EC of 8 April 2005 laying down principles and detailed guidelines for good clinical practice as regards investigational medicinal products for human use, as well as the requirements for authorisation of the manufacturing or importation of such products. Official Journal of the European Union. 2005;L 91, 9/4/2005:13–19. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/pharmaceuticals/eudralex/vol-1/dir_2005_28/dir_2005_28_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verordnung über die Anwendung der Guten Klinischen Praxis bei der Durchführung von klinischen Prüfungen mit Arzneimitteln zur Anwendung am Menschen [Regulation on the implementation of Good Clinical Practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products for human use]. GCP-Verordnung vom 9. August 2004 (BGBl. I S. 2081), die zuletzt durch Artikel 4 der Verordnung vom 3. November 2006 (BGBl. I S. 2523) geändert worden ist. Berlin: Bundesministerium der Justiz; [cited 2009 Jul 07]. Available from: http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/gcp-v/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte [Statistics of the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices] Genehmigungsverfahren Statistik. Bonn: BfArM; [updated: 2008 Feb 26; cited 2009 Jul 07]. Available from: http://www.bfarm.de/cln_012/nn_1198686/DE/Arzneimittel/1__vorDerZul/klinPr/klin__prf__genehm/Statistik.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paul-Ehrlich-Institut. Statistics on the requests for clinical trial authorisations. Langen: PEI; [created: 2007 Feb 27; updated: 2009 Feb 05; cited 2009 Jul 07]. Available from: http://www.pei.de/cln_116/nn_275200/EN/infos-en/pu-en/02-clinical-trials-pu-en/statistics/statistics-content-en.html#doc275246bodyText9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.