Summary

The large subunit of RNA Polymerase II, Rpb1, undergoes hydroxylation on proline 1465, which in turn triggers Ser5 hydroxylation. While Egln2 prolyl hydroxylase appears to mediate P1465 hydroxylation, Egln1 has an inhibitory activity and its knockdown stimulates constitutive hydroxylation and Ser5 phosphorylation of Rpb1, but only in cells that are VHL(+). In this study we have analyzed protein factors affected by the knockdown of Egln1 in VHL(+) and VHL(−) cells. We found that, in VHL(+) cells, several proteins were inhibited but none were induced by Egln2 knockdown. The function of several of those proteins was related to calcium metabolism and the cytoskeleton. In contrast, in VHL(−) cells Egln1 knockdown caused upregulation of several mitochondrial proteins including subunits of ATP synthase. Several of the proteins repressed in VHL(−) cells by Egln1 knockdown were involved in the function of RNA polymerase II during transcription from chromatin templates. These data suggest that the effects of Egln1 knockdown depend on the status of pVHL and can be correlated with effects on Rpb1.

Introduction

The oxygen-dependent prolyl hydroxylases, the Eglns (Egln1-3), were originally characterized as the family of enzymes that hydroxylate prolines with LXYLAP motifs in the oxygen-dependent degradation domains (ODDD) within the alpha subunits of the hypoxia-inducible transcription factor (HIF) (Epstein et al., 2001). The Eglns, similar to the collagen prolyl hydroxylases, utilize molecular oxygen, 2-oxoglutarate, Fe(II), and acscorbate for the hydroxylation reaction (Kaelin, 2005; Fong and Takeda, 2008). The obligate dependence on O2 level for Egln function defines these enzymes as oxygen sensors. They are responsible for regulation of cell function during hypoxia through the control of HIF levels. This control is achieved by permitting ubiquitylation of the HIF alpha subunits by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor complex (Ivan et al., 2001; Jaakola et al., 2001; Appelhoff et al., 2004). The dependence on 2-oxoglutarate couples the activity of the prolyl hydroxylases with the Krebs cycle and cellular metabolic activity; and with the Krebs cycle intermediates, fumarate and succinate, which act as powerful competitive inhibitors of oxoglutarate. Hydroxylation of HIF-α prolines is also sensitive to reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can oxidize Fe(II), oxoglutarate, and ascorbate or have a direct oxidizing effect on the Eglns (Burnelle at al., 2005; Gerald et al., 2004).

All three Eglns have been shown to exercise hydroxylating activity towards HIF-αs under some conditions, with Egln1, which is directly responsible for hydroxylation and subsequent pVHL-dependent ubiquitylation and degradation during normoxia, having the strongest activity (Berra et al., 2003). Egln3 seems to be able to mediate some hydroxylation of HIF-αs during hypoxia, thus limiting hypoxic accumulation of HIF (Nakayama et al., 2004). The role of Egln2 in regulation of HIFs is somewhat less clear, yet it is necessary for oxidative metabolism and its knockout stimulates anaerobic ATP production in a mechanism that is HIF-2 dependent (Aragones et al., 2008).

Prolyl hydroxylases have activities that are unrelated to HIF function. The LXYLAP motif is present on several different proteins, which are likely to be subject to hydroxylation. In that respect, a novel target for Egln2 is IκB kinase, where hydroxylation of proline P191 within the LQYLAP inhibits NFκB activity (Cummins et al., 2006). In addition, it is possible that other HIF-prolyl hydroxylases can hydroxylate prolines in currently unknown motifs. For example, while it is known that Egln3 is necessary and sufficient for induction of apoptosis in PC12 cells in response to NGF withdrawal, the target of its hydroxylating activity is currently unknown (Lee et al., 2005). Interestingly, in the fly, the cyclinD/cdk4 complex appears to regulate growth but not proliferation of Drosophila cells in a manner requiring HpH, the fly equivalent of prolyl hydroxylases (Frei & Edgar, 2004).

Our laboratory reported that the large subunit of RNA Polymerase II, Rpb1, has an LXXLAP motif with P1465 in the proximity of the regulatory C-terminal domain (CTD) of Rpb1. This motif is located on the surface of the RNA Polymerase II complex in the pocket between Rpb1 and another subunit, Rpb6, and shows sequence and structural similarity to the motifs on HIF-αs (Kuznetsova et al., 2003). Importantly, hydroxylation of P1465 occurs on Rpb1 engaged on the DNA, is induced by oxidative stress, and in turn stimulates phosphorylation of Serine-5 residues within CTD, thus regulating gene expression (Mikhaylova et al., 2008). Both Egln1 and Egln2 are in the complex with Rpb1 that is induced by oxidative stress, and the knockdown of Egln2 has been shown to abolish P1465 hydroxylation, implicating Egln2 as an Rpb1 hydroxylase. However, knockout of Egln1, significantly induced constitutive P1465 hydroxylation and Ser5 phosphorylation of Rpb1, and prevented further induction by oxidative stress. This constitutive effect was mediated by both Egln2 and Egln3. Thus, while Egln2 and Egln3 act as proline hydroxylases of Rpb1, Egln1 has an unexpected inhibitory effect on this process (Mikhaylova et al., 2008).

In view of the strong effect of Egln1 knockdown on Rpb1 P1465 hydroxylation and Ser5 phosphorylation, we set out to determine how the loss of Egln1 activity in 786-O VHL(−) and VHL(+) cells affects protein expression. To do this, we used iTRAQ labeling techniques for relative quantitation and identification of differentially-expressed proteins. These iTRAQ methods, which originated from the isotope-codes affinity tag (ICAT) approach reported by Gygi et al. (1999), have the added advantages of using labeling chemistry targeted at primary amines (rather than sulfhydryl groups) and the ability to simultaneously measure relative quantities of proteins under multiple conditions (Ross et al., 2004). Using these iTRAQ labeling methods, we demonstrate that a similar loss of Egln1 in VHL(+) and (−) cells leads to very different changes in the protein profiles, which is dependent on the status of pVHL.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and preparation of total cellular lysates

786-O VHL(−), VHL(+), VHL(−)/Egln1kd and VHL(+)/Egln1kd cells were obtained and cultured as described before (Mikhaylova et al., 2008). Total cellular lysates were obtained as described before (Mikhaylova et al., 2008). Briefly, cells were homogenized in hypotonic buffer with 40 strokes of a Dounce homogenizer (pestle A). NaCl was then added drop wise to a final concentration of 300 mM and homogenates were extracted for 30 min at 4°C. This was followed by digestion with DNase and micrococcal nuclease for 1 h at 4°C. In the final extract, NP40 was added to a final concentration of 0.5% and NaCl was added to 500 mM. Extracts were then centrifuged for 20 min at 14,000 rpm and stored at −80°C.

Protein quantitation and iTRAQ labeling

Cellular extracts from VHL (+) and VHL (−) cells with Egln 1 activity suppressed by lentiviral vector shRNA were quantified for protein content using the non-interfering (NI) protein-assay reagents from G-Biosciences (Maryland Heights, MO) according the vendors instructions. Six volumes of cold acetone were added to the appropriate quantity of extract from each condition to precipitate 200 μg of protein. After centrifugation (13,000 × g for 10 minutes), the supernatant was carefully removed and the protein pellet was washed with 70% cold acetone. The samples were centrifuged again, the supernatant removed, and the resulting pellets dissolved in iTRAQ dissolution buffer. Trypsin digestion and iTRAQ labeling were performed according the vendor’s instructions (Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex, Foster city, CA) with one modification; because we used twice the suggested amount of protein, we used two vials of iTRAQ labeling reagent for each sample. As is outlined in Figure 1, the trypsin-digested extracts from VHL(+)/Egln1kd, VHL(+), VHL(−)/Egln1kd, and VHL(−) cells, were labeled with iTRAQ reagent 114, 115, 116, and 117, respectively. Water was added to each sample after labeling to stop the reactions. All of the iTRAQ-labeled samples were mixed together for subsequent separation, quantitation, and identification.

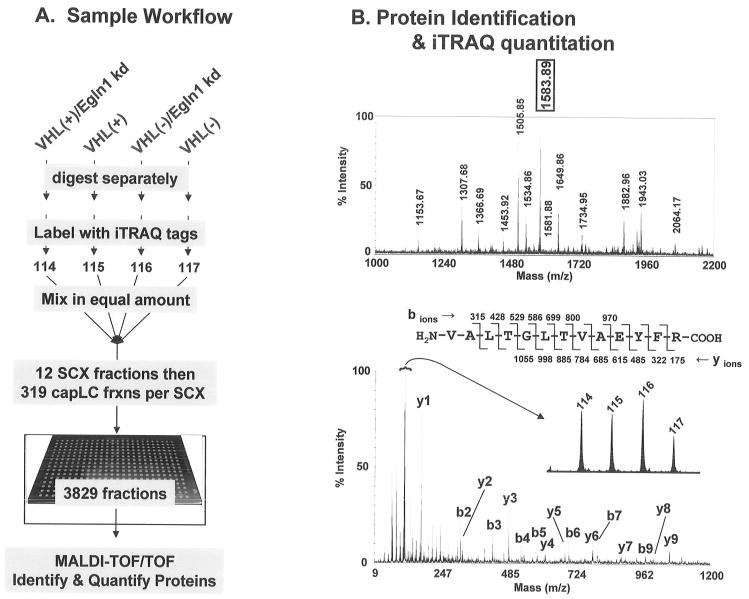

Figure 1.

The iTRAQ work flow and example data. Panel A: equal quantities of four cellular extracts were digested with trypsin, tagged with iTRAQ reagents, separated by strong cation exchange (SCX) and capillary liquid chromatography (capLC), and then identified and quantified by MALDI-TOF/TOF, all as described in the Materials and Methods section. Panel B: an example of a MALDI peptide spectrum from SCX fraction 9, capLC fraction 126 (upper panel) and the MS/MS fragmentation spectrum from M+H=1583.89 (lower panel). The sequence information is sufficient to identify ATP5B (Table 3) while the released iTRAQ tags (inset) provide the relative quantitation of this protein from the 4 conditions evaluated.

Ion-exchange chromatography of the labeled peptides

The complex mixture of iTRAQ-labeled peptides was concentrated by vacuum centrifugation with a Speed-Vac concentrator to about 30 μl then suspended to 1 ml with 10 mM potassium phosphate (KH2PO4) in 25% acetonitrile, pH 3.0 (buffer A) and adjusted to pH 3.0 with phosphoric acid. The sample was then fractionated by strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatography on an AKTA purifier HPLC (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) using a 4.6 mm internal diameter (ID) × 200 mm length PolyLC Polysulfoethyl A column packed with 5 μm beads with 300 Å pores (The Nest Group, Southborough, MA). A 4.6 mm ID × 10 mm length guard column of the same material was attached. The sample was loaded onto the column and washed in 10 mM KH2PO4 in 25% acetonitrile, pH 3.0 for 20 minutes at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min to remove excess reagent. Retained peptides were eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 500 mM potassium chloride (in 10 mM KH2PO4 in 25% acetonitrile, pH 3.0) over 40 minutes at 1.0 ml/min. Twelve fractions were collected from the SCX column. Each of the fractions was concentrated and desalted on an Oasis HLB 1 cc (10mg) extraction cartridge, as described by the manufacturer (Waters, Milford, MA). The desalted samples were concentrated to about 10 μl in a Speed-Vac concentrator and suspended to 25 μl in 0.1% formic acid for subsequent LC-MALDI separation and analysis.

Tempo-LC MALDI separation

All fractions were separated and spotted on Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) target plates using a Tempo LC MALDI sample-spotting system (Applied Biosciences/MDS Sciex). Individual SCX fractions were injected and captured on a 200 μm ID × 5 mm length PepSwift monolithic trap column (Dionex-LC Packings, Hercules, CA) and then eluted onto a 100 um ID × 150 mm length Chromolith CapRod monolithic column (Merck Darmstadt, Germany). The peptides retained were washed at a flow rate of 3 μl/min in 92% solvent A (2% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) for 2 minutes and then eluted using a gradient ranging from 8% to 80% solvent B (98% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) over 20 minutes. The column effluent was mixed on line at a 1:1 ratio with MALDI matrix (5 mg/mL alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 60% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid + 10 mM ammonium phosphate (monobasic). The resulting effluent was spotted onto blank Opti-TOF LC/MALDI plates from min 5 to min 21 of the LC run resulting in 319 spots per run or a total of 3828 MALDI-TOF spots from the 12 SCX fractions.

MALDI-TOF/TOF MS

MALDI plates were analyzed on a 4800 Proteomics Analyzer (MALDI-TOF/TOF) using 4000 series Explorer software (Applied Biosystems/MDS Analytical Technologies). A mass spectrum was generated from each spot in positive ion mode in the mass range of m/z 775 to 4000 by averaging 800 laser shots. A maximum of fifteen of the most abundant precursors per spot with a minimum S/N filter of 30 and a fraction-to-fraction precursor mass tolerance of 100 ppm were selected for MS/MS analysis with the weakest ion analyzed first. On average, 1500 MS/MS spectra per SCX fraction (or about 18000 MS/MS total) were collected by averaging 1000 laser shots per MS/MS spectrum. Peptides were fragmented at 2 kV with air as the CID gas to produce the MS/MS fragmentation spectra.

Protein identification and quantitation

Peptide identification was performed by searching each MS/MS spectrum against the NCBInr database of Homo sapiens protein sequences by using the MASCOT search algorithm on a local server (Version 2.2.04, Matrix Science, London UK) and GPS Explorer software integrated into the MALDI-TOF/TOF system (Version 3.6, Applied Biosystems/MDS Analytical Technologies). N-term_iTRAQ and lysine(K)_iTRAQ were selected as fixed modifications and deamidated (NQ), MMTS(C), and oxidation (M) were selected as variable modifications. A maximum of 2 missed tryptic cleavages were allowed and the MS/MS fragment and precursor tolerances were set to 0.3 Da and 100 ppm, respectively. A minimum ion score C.I. % for peptides of at least 85 was also a required criterion. The iTRAQ ratio results used for quantification were normalized using the median ratios for all proteins in the sample to account for small changes in the reagent labeling. To consider a protein for further statistical analysis, a total ion score of at least 75 was required. A fold difference of at least 0.5 was needed to consider a protein upregulated or downregulated.

Results and Discussion

Egnl1 knockdown with shRNA

The use of specific shRNA lentiviral constructs to knock down Egln1 efficiently decreased the amount of Egln1 protein in both VHL(+) and VHL(−) cells, resulting in decreases of approximately 90% or larger (Mikhaylova et al., 2008). This knockdown resulted in a significant induction of P1465 hydroxylation and Ser5 phosphorylation of Rpb1 engaged on the DNA in VHL(+)/Egln1kd cells but not in VHL(−)/Egln1kd cells (Mikhaylova et al., 2008). However, levels of HIF-2α were comparable between both sets of cells, and similar to those in VHL(−) cells.

iTRAQ labeling, identification, and quantification

As depicted in Fig 1A, iTRAQ-labeled samples were separated into 12 SCX fractions that were each then separated into 319 capillary liquid chromatography (capLC)-MALDI spots for a total of 3828 samples for analysis by MALDI-TOF/TOF. MS/MS fragmentation spectra were collected from over 18,000 peptide signals. An example of the protein identification and quantitation data is depicted in Figure 1B. The upper panel shows the peptide spectrum from one of the 3828 capLC-MALDI fractions while the lower panel demonstrates how a single peptide (M+H=1583.89 in the upper panel) can be isolated and fragmented in the TOF/TOF instrument to acquire data for both the protein identification (from the fragmentation) and relative quantitation (from the iTRAQ tags). Upon collectively searching all of the 18,000 MS/MS data for protein identification, over 600 proteins were uniquely identified and quantified. As expected, the vast majority of proteins showed no quantitative change across the conditions analyzed (data not shown); however, detailed quantitative analysis revealed 13 proteins regulated by Egln1 knockdown in VHL(+) cells (Tables 1 & 2). Sixteen other proteins were induced (Tables 3 & 4) and 26 proteins were repressed (Tables 5 & 6) by Egln1 knockdown in VHL(−) cells. A detailed discussion of each of these groups of proteins is provided below.

TABLE 1. iTRAQ Identification of Proteins Specifically Regulated by Egln1 Knockdown in VHL(+) Renal Carcinoma Cells.

Fold change in the protein level in VHL(+)/Egln1kd cells vs. VHL(+) cells. 2-fold difference: above 2.088 or below 0.522; 0.75-fold difference: above 1.827 or below 0.597; 0.6-fold difference: above 1.670 or below 0.653; 0.5-fold difference: above 1.566 or below 0.696

| Protein | Function | Accession No. | Protein MW | Protein PI | Pep. Count | Total Ion Score | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLNB | Filamin b, beta (actin binding protein 278), isoform cra_e | gi|119585761 | 302605.8 | 5.66 | 11 | 857 | 0.6810 |

| TPM4 | Tropomyosin 4 | gi|4507651 | 32251.1 | 4.67 | 7 | 421 | 0.6619 |

| TPM2 | Tropomyosin 2 (beta) isoform 2 | gi|47519616 | 38013.2 | 4.63 | 7 | 411 | 0.6935 |

| FSCN1 | Similar to singed (Drosophila)-like (sea urchin fascin homolog like) | gi|14043297 | 49057.0 | 6.61 | 3 | 334 | 0.6303 |

| 1CYN A | Chain A, Cyclophilin B Complexed wth [d-(Cholinylester)ser8 - Cyclosporin] | gi|1310882 | 22962.6 | 9.18 | 4 | 273 | 0.6743 |

| CALD1 | Caldesmon 1 isoform 4 | gi|15149463 | 74593.1 | 6.66 | 2 | 245 | 0.5862 |

| POR | NADPH--cytochrome P450 reductase | gi|2851393 | 81973.0 | 5.38 | 2 | 148 | 0.6820 |

| PON2 | Serum paraoxonase/arylesterase 2 | gi|6174935 | 42110.9 | 5.26 | 1 | 97 | 0.5546 |

| SYNPO | Synaptopodin | gi|40353727 | 100804.2 | 9.79 | 1 | 96 | 0.5412 |

| RCN2 | Reticulocalbin 2, EF-hand calcium binding domain | gi|119619622 | 45027.5 | 4.49 | 1 | 91 | 0.6667 |

| 1FO2 A | Chain A, Crystal Structure of Human Class I Alpha1,2-Mannosidase in Complex with 1- Deoxymannojirimycin | gi|13096545 | 56425.6 | 6.35 | 1 | 81 | 0.6398 |

| CALC | Atopy related autoantigen CALC | gi|3297882 | 39850.8 | 7.22 | 1 | 80 | 0.6695 |

| CALR* | Calreticulin = calcium binding protein | gi|913156 | 11943.6 | 4.12 | 1 | 78 | 0.6954 |

TABLE 2.

Functional Assignment for Proteins Identified as Decreased by Egln1 Knockdown in VHL(+) Renal Carcinoma Cells

| Protein | Function |

|---|---|

| FLNB | Actin-binding protein (calponin homology domain, calcium dependent), cytoskeleton |

| TPM4 | Tropomyosin 4 [Homo sapiens] |

| TPM2 | Tropomyosin 2 (beta) isoform 2 [Homo sapiens] |

| FSCN1 | Actin-binding, higher expression correlates with higher grades of tumor, motility, and invasiveness, interacts directly with VHL, chr 7 |

| 1CYN A | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase activity, inhibitor of calcium and calmodulin dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin |

| CALD1 | Calmodulin and actin binding (calcium dependent), inhibitor of actin-tropomyosin interaction, suppressor of cancer cell invasion, chr 7 |

| POR | NADPH--cytochrome P450 reductase, associated with endoplamic reticulum and micorsomes, drug metabolism |

| PON2 | Serum paraoxonase/arylesterase 2 has anti-oxidative activity |

| SYNPO | Actin-associated, regulates cell migration in kidney podocytes, protects against proteinuria, chr 5 |

| RCN2 | Multiple EF-hand calcium-binding domains, associated with Bardet-Biedl syndrome (disorder of retina and kidney) chr 15 |

| 1FO2 A | Chain A, Crystal Structure Of Human Class I Alpha1,2-Mannosidase In Complex With 1-Deoxymannojirimycin |

| CALC | Calcium-binding, EF-hand-containing, chr 10 |

| CALR* | Calcium-binding, regulates transcription (interacts with nuclear receptors), implicated in hypoxia, associated with colon and bladder cancer, interacts with mRNA of C/EBP, expressed in metastatic melanomas, chr 19 |

TABLE 3. iTRAQ Identification of Proteins Specifically Up-regulated by Egln1 Knockdown in VHL(−) Renal Carcinoma Cells.

Fold change in the protein level VHL(−)/Egln1kd cells vs. VHL(−) cells. 2-fold difference: above 2.112; 0.75-fold difference: above 1.848; 0.6-fold difference: above 1.690; 0.5-fold difference: above 1.584.

| Protein | Function | Accession No. | Protein MW | Protein PI | Pep. Count | Total Ion Score | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP5B | Mitochondrial ATP synthase, H+ transporting F1 complex beta subunit | gi|89574029 | 51109.2 | 4.95 | 13 | 1104 | 1.7197 |

| ATP5A | ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial F1 complex, alpha subunit 1 | gi|15030240 | 64238.8 | 9.07 | 8 | 670 | 1.9214 |

| MRCL3 | Myosin regulatory light chain MRCL3 | gi|5453740 | 21943.0 | 4.67 | 4 | 267 | 1.6127 |

| SLC25A5 | Solute carrier family 25, member 5 | gi|156071459 | 36289.6 | 9.71 | 4 | 253 | 2.1506 |

| SLC25A6 | Solute carrier family 25, memberA6 | gi|156071462 | 36159.5 | 9.76 | 4 | 247 | 2.2699 |

| BASP1 | Brain abundant, membrane attached signal protein 1 | gi|12653493 | 27363.4 | 4.67 | 3 | 200 | 1.5852 |

| MYO1C | Myosin 1C | gi|45751608 | 127386.6 | 9.48 | 3 | 184 | 1.5852 |

| NUPL2 | Nucleoporin 205kDa | gi|57634534 | 240888.6 | 5.83 | 3 | 161 | 1.6515 |

| NDUFA5 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 5 | gi|47682777 | 15335.5 | 5.75 | 1 | 158 | 1.9214 |

| MYO1B | Myosin-lb | gi|68583739 | 147609 | 9.43 | 2 | 156 | 1.6402 |

| ATP5O | ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial F1 complex, O subunit | gi|54696534 | 25884.5 | 10.00 | 1 | 123 | 2.4129 |

| ATAD3A | ATPase family AAA domain-containing protein 3A | gi|84028405 | 76656.5 | 9.08 | 2 | 115 | 1.8665 |

| TOMM20 | translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20 homolog | gi|48145553 | 18002.9 | 8.80 | 1 | 113 | 1.8324 |

| UQCRH | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase hinge protein | gi|83627705 | 11596.5 | 4.39 | 1 | 111 | 2.4716 |

| SLC2A2 | Glucose transporter glycoprotein | gi|3387905 | 39584.4 | 7.59 | 2 | 89 | 1.7547 |

| ATP5F1 | ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial F0 complex, subunit B1 precursor | gi|21361565 | 31916.5 | 9.37 | 1 | 75 | 3.7311 |

TABLE 4.

Functional Assignment for Proteins Identified as Increased by Egln1 Knockdown in VHL(−) Renal Carcinoma Cells

| Protein | Function |

|---|---|

| ATP5B | Beta subunit of catalytic core of mitochondrial ATP synthase |

| ATP5A | Alpha subunit of catalytic core of mitochondrial ATP synthase |

| MRCL3 | Myosin regulatory light chain 3 |

| SLC25A5 | Mitochondrial adenine nucleotide transporter promoting growth and proliferation; required for cancer cell glycolysis |

| SLC25A6 | Mitochondrial adenine nucleotide transporter; dominantly stimulates apoptosis; participates in TNF-induced apoptosis |

| BASP1 | Expressed in podocytes; transcriptional cosuppressor working with Wilms’ Tumor suppressor. |

| MYO1C | Unconventional myosin. Nuclear localization and association with RNA Polymerase I and II complexes in regulation of transcription association. |

| NUPL2 | Nucleorporin, member of the nuclear envelope; participates in docking of the viral DNA |

| NDUFA5 | B13 subunit of complex I of the mitochondrial respiratory chain located in the inner mitochondrial membrane |

| MYO1B | Actin binding; regulates intracellular trafficking of protein cargo in multivesicular sorting endosomes |

| ATP5O | Component of a the F-type ATP synthase in the mitochondrial matrix |

| ATAD3A | Component of mitochondrial nucleoids; binds to displacement loop in the major noncoding region |

| TOMM20 | Translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane participating in recognition of pre-proteins. |

| UQCRH | Mitochondrial Hinge protein. Reduced expression in ovarian and breast cancer due to hypermethylation; break point gene in Ewing sarcoma. |

| SLC2A2 | Glucose transporter 2, integral plasma membrane glycoprotein; glucose sensing |

| ATP5F1 | Beta subunit of the proton channel of mitochondrial ATP synthase |

TABLE 5. iTRAQ Identification of Proteins Specifically Down-regulated by Egln1 Knockdown in VHL(−) Renal Carcinoma Cells.

Fold change in the protein level VHL(−)/Egln1 kd cells vs. VHL(−) cells. 2-fold difference: below 0.528; 0.75 fold-difference: below 0.603; 0.6-fold difference: below 0.660; 0.5-fold difference: below 0.704.

| Protein | Function | Accession No. | Protein MW | Protein PI | Pep. Count | Total Ion Score | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANXA1 | Annexin 1 | gi|4502101 | 43445.4 | 6.57 | 10 | 929 | 0.6477 |

| GDI2 | Human rab GDI | gi|285975 | 56107.7 | 5.94 | 4 | 436 | 0.6941 |

| HADHA | Mitochondrial trifunctional protein, alpha subunit precursor | gi|20127408 | 93322.2 | 9.16 | 3 | 314 | 0.6951 |

| P4HB | Prolyl 4-hydroxylase, beta subunit precursor | gi|20070125 | 63997.6 | 4.76 | 4 | 278 | 0.6774 |

| CNN3 | Calponin 3 | gi|4502923 | 39993.3 | 5.69 | 3 | 248 | 0.5275 |

| SET | SET translocation isoform 1 | gi|170763500 | 36927.1 | 4.23 | 2 | 244 | 0.5985 |

| AKR1B1 | Aldo-keto reductase, member B1 | gi|4502049 | 39577.1 | 6.51 | 3 | 236 | 0.6686 |

| CCT3 | T-complex polypeptide 1 | gi|36796 | 66119.8 | 6.03 | 2 | 159 | 0.678 |

| LARP3 | Chain A, Crystal Structure Of N-Terminal Domains Of Human La Protein | gi|187609149 | 26227.3 | 6.28 | 2 | 156 | 0.5833 |

| ASPH | Aspartyl (asparaginyl) beta- hydroxylase | gi|1911652 | 93619.0 | 4.92 | 3 | 152 | 0.5246 |

| PLOD | Lysyl hydroxylase | gi|190074 | 88859.2 | 6.47 | 2 | 150 | 0.6269 |

| COPE | Epsilon subunit of coatomer protein complex isoform a | gi|31542319 | 36621.9 | 4.97 | 1 | 137 | 0.6998 |

| NASP | Histone-binding protein | gi|184433 | 94361.6 | 4.27 | 2 | 135 | 0.5227 |

| PARP1 | Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase | gi|190167 | 131312.4 | 9.02 | 1 | 129 | 0.6903 |

| VAT1 | VAT1 protein | gi|32425722 | 44457.4 | 6.17 | 1 | 128 | 0.5161 |

| CPSF6 | Cleavage and polyadenylation specific factor 6, 68 kD subunit | gi|162329583 | 61623.1 | 6.66 | 1 | 115 | 0.5634 |

| SLC7A5 | Solute carrier family 7, member 5 | gi|24981008 | 58128.6 | 8.17 | 1 | 104 | 0.6042 |

| NHP2L1 | PREDICTED similar to Nhp2 non-histone chromosome protein 2-like 1 | gi|109094377 | 8759.8 | 7.74 | 1 | 101 | 0.6932 |

| SMEK1 | SMEK homolog 1 | gi|74736507 | 104098.2 | 4.83 | 1 | 99 | 0.6894 |

| PRDX6 | Peroxiredoxin 6 | gi|54303999 | 10577.5 | 5.51 | 1 | 92 | 0.4612 |

| GLS | Glutaminase isoform C | gi|6002671 | 63556.8 | 6.05 | 1 | 90 | 0.5805 |

| ARL6IP5 | ADP-ribosylation-like factor 6 interacting protein 5 variant | gi|62898864 | 23127.5 | 9.88 | 1 | 90 | 0.589 |

| HPIBP3 | HP1-BP74 | gi|56676330 | 72697.4 | 9.69 | 1 | 86 | 0.482 |

| HIPIR | KIAA0655 protein | gi|3327124 | 130482.6 | 6.41 | 1 | 81 | 0.6648 |

| CALR* | Calreticulin-calcium binding protein | gi|913156 | 11943.6 | 4.12 | 1 | 78 | 0.6051 |

| RNASET2 | Ribonuclease T2, isoform CRA e | gi|119567903 | 21813.4 | 8.14 | 1 | 76 | 0.4669 |

TABLE 6.

Functional Assignment for Proteins Identified as Decreased by Egln1 Knockdown in VHL(−) Renal Carcinoma cells

| Protein | Function |

|---|---|

| ANXA1 | Ca2+-dependent phospholipid-binding protein; inhibits phospholipaseA2; anti-inflammatory; decreased expression in several cancers including thyroid and prostate |

| GDI2 | Rab GDI, interacts with RABs 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, regulating endo/exocytosis, expressed in pancreatic carcinomas (with cyclin I) |

| HADHA | Mitochondrial membrane-bound component of a complex with enzymatic activity of 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase and enoyl-CoA hydratase activity, last steps in beta-oxidation of long-chain fatty acids. |

| P4HB | Belongs to protein disulfide isomerase family; mature enzyme composed of two alpha and two beta subunits hydroxylates prolines in 2-oxoglutararte 4-dioxygenase-dependent manner; binds to superoxide dismutase. |

| CNN3 | Acidic calponin 3 is associated with the cytoskeleton, interacts with F-actin, but not with microtubules, desmin filaments, tropomyosin, or calmodulin |

| SET | Nuclear oncogene.required for transcription from chromatin templates by RNA Polymerase II. Histone chaperone. |

| AKR1B1 | Aldose reductase, including aldehyde formed from glucose; putative tumor suppressor located on chromosome 7q35. |

| CCT3 | Molecular chaperone, member of chaperonin-containing TCP1 complex (CCT) or TCP1 ring complex (TRiC); overexpressed in hepatocallular carcinoma, folds actin, tubulin and other cytoskeleton-related proteins, interacts directly with VHL |

| LARP3 | La protein (SSB, also known as LARP3) recognizes 3′poly(U) sequence of RNA Polymerase III transcripts and participates in final maturation of the transcripts |

| ASPH | Calcium homeostasis; overexpressed in biliary, hepatocellular, and colon cancer. Hydroxylates aspartic acid and asparagine in EGF-like domains of proteins. |

| PLOD | Bound to the endoplasmic reticulum membranes; hydroxylates lysine residues in collagen |

| COPE | Subunit of coatomer protein complex located in cytoplasm and regulating trafficking of non-clathrin coated vesicles. Binds to the dilysine motifs. |

| NASP | Involved in transporting histones into the nucleus of dividing cells, plays a role in DNA replication and repair through its association with ASF1 anti-silencing function 1 homolog A; also interacts with unc-51-like kinase 2 (ULK2), which is located within the Smith-Magenis syndrome region on chromosome 17. |

| PARP1 | Chromatin-associated enzyme which, by poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of other proteins, loosens chromatin structure. Interacts with SET in regulation of chromatin templates. |

| VAT1 | Vesicle amine transport protein 1 homolog; belongs to zinc-containing alcohol dehydrogenase proteins. |

| CPSF6 | 68 kDa subunit of a cleavage factor required for cleavage and polyadenylation of the 3′ end of transcripts |

| SLC7A5 | L-type amino acid transporter for large neutral amino acids. Promotes tumor growth. |

| NHP2L1 | Localizes to splicing speckles, Cajal bodies, and nucleoli in RNA polymerase II transcription-dependent manner, and likely regulates splicing as the snRNPs NHP2L1 binds to are integral to the spliceosome; interacts directly with POLA2 and CDKN2C, which inhibits CDK4 |

| SMEK1 | Suppressor of mek1 (MAP2K1 MAP-type kinase), membrane associated (containing pleckstrin-homology domain), interacts with PP4 phosphatase that targets Cdk1, NFkappaB, and JNK; also interacts with filamin FLNA, which is critical for blood vessel development. |

| PRDX6 | Thio-specific antioxidant protein. Reduces H2O2, phospholipid, and short fatty acid hydroperoxides. Overexpression leads to invasive phenotypes in breast cancer. |

| GLS | Enzyme yielding glutamate from glutamine. Increased in melanoma. |

| ARL6IP5 | Associated with cytoskeleton and cell differentiation; regulates glutamate transport. |

| HPIBP3 | Heterochromatin-binding protein |

| HIPIR | Huntington-interacting protein-related protein; binds to clathrin and regulates clathrin assembly and intracellular trafficking |

| CALR* | Calcium binding, regulates transcription (interacts with nuclear receptors), implicated in hypoxia, associated with colon and bladder cancer, interacts with mRNA of C/EBP, expressed in metastatic melanomas, chr 19 |

| RNASET2 | Extracellular ribonuclease. Tumor suppressor. Its decreased concentration is associated with melanoma and an invasive form of ovarian cancer. |

Proteins affected by Egln1 knockdown in VHL(+) cells

Table 1 lists 13 proteins that were significantly regulated by knockdown of Egln1 in VHL(+) cells as compared with sham-treated cells. Interestingly, this regulation consisted entirely of downregulation, with protein levels exhibiting decreases from 50% to 75% as compared with sham-treated cells. Table 2 provides a functional association for all the identified proteins. Very interestingly, the activity of most of the identified proteins was related to the cytoskeleton and to calcium signaling. Proteins that are calcium binding, or that bind to the calcium-binding proteins were clearly overrepresented (Table 2). Several proteins were also associated with vascularization (including vascularization of tumors, see, e.g., caldesmon and calreticulin). In addition, we detected multiple associations with the HLA locus and other immune system genes (Rizvi et al., 2004; Sadasivan et al., 1996). We observed links with von Willebrand factor, which interacts with calreticulin (Allen et al., 2000). von Willebrand factor’s receptor, GP1BA (Huizinga et al., 2002), interacts with filamin B and several coagulation factors and other platelet-adhesion and vascular-injury-related proteins (Willamson et al., 2002). Some of these relationships are indirect. For example, filamin B interacts with fibronectin receptors, such as ITGB1 integrin, which is involved in the immune response and in the metastatic diffusion of tumor cells (van der Flier et al., 2002). Interestingly, a related protein filamin A, interacts directly with pVHL (Tsuchiya et al., 1996). Caldesmon expression suppresses cancer cell invasion, and its downregulation could contribute to cancer progression (Yoshio et al., 2007). In turn, synaptopodin, which regulates actin organization and cell motility, protects against proteinuria by disrupting Cdc42:IRSp53:Mena signaling complexes in kidney podocytes (Asanuma et al., 2006). Thus, downregulation of synaptopodin might contribute to an increased kidney filtration barrier that involves the podocyte actin cytoskeleton. On the other hand, higher levels of fascin-1 correlate with the invasiveness and severity of cancer (fascin-1 also interacts directly with VHL, based on high-throughput mass-spectrometry evidence (Ewing et al., 2007). Therefore, a decrease in cell motility would be an expected result of the downregulation of fascin.

The activity of two of the identified proteins, POR and PON2, is related to the cell’s responsiveness to oxidative stress. POR, P450 cytochrome oxidoreductase, affects the metabolism of a large number of drugs, some used in cancer, and thus has a major role in the effect of cancer therapeutics. Recently, its polymorphism has been related to breast cancer risk (Haiman et al., 2007). PON2 reduces oxidative stress (Horke et al., 2007), and as such could act as a protector against cancer; however, its role in cancer has not yet been thoroughly investigated.

The fact that the cytoskeleton-, calcium-, and oxidative stress-related proteins mentioned above are downregulated in cells exhibiting high levels of P1465 hydroxylation, Ser-5 phosphorylation, and Rpb1 ubiquitylation caused by knockdown of Egln1 supports the potential role of these modifications in inhibiting gene expression. Similarly, we have previously demonstrated that induction of the above modifications of Rpb1 induced by low-grade oxidative stress inhibits several cytoskeleton- and oxidative-stress-regulated protein factors. Further analysis of the mechanisms of this downregulation will be investigated.

Proteins affected by Egln1 knockdown in VHL(−) cells

In contrast to the effects in VHL(+) cells, the knockdown of Egln1 in VHL(−) cells resulted in both increases and decreases in the expression of different proteins. The levels of 16 proteins were induced, 10 of which were mitochondrial proteins (Tables 3 and 4). In particular, we observed induction of three subunits of mitochondrial ATP synthase: subunits alpha and beta of the catalytic core, and the beta subunit of the proton channel. Another subunit of ATP synthase induced by Egln1 knockdown in VHL(−) cells was ATP5O, a protein that confers oligomycin sensitivity. In addition, there was a significant induction in the expression of subunit B13 of complex I, or mitochondrial respiratory chain. Other affected mitochondrial proteins were transporters, two of adenine nucleotides, with very different functions. While SLC25A5 promotes cell growth and proliferation (Chevrollier et al., 2005), SLC25A6 stimulates apoptosis (Yang et al., YEAR). These results imply that knockdown of Egln1 in VHL(−) cells may specifically stimulate mitochondrial activity and oxidative phosphorylation. This is an intriguing observation in view of the fact that in tumors, including kidney cancer, there is a major increase in ATP production from glycolysis, as opposed to the mitochondrial respiratory chain.

One of the identified proteins, BASP1, is a transcriptional co-repressor that works with the Wilms tumor suppressor (Carpenter et al., 2004). This protein is expressed in the developing kidney (e.g., in podocytes) in a manner coinciding with the expression of the Wilms tumor suppressor. This implies that a protein that supports tumor suppressor function is induced in response to Egln1 knockdown.

In addition to the proteins whose levels were induced by Egln1 knockdown in VHL(−) cells, there were proteins that were repressed under these conditions (Tables 5 and 6). The nature of these proteins was, however, different from the proteins repressed by Egln1 knockdown in VHL(+) cells (compare Tables 2 and 6). Interestingly, a group of proteins with related functions emerges from this analysis, these being proteins that seem to regulate the chromatin-dependent activity of RNA polymerases and the processing of transcripts. Perhaps the most interesting is the decrease in two functionally linked proteins, PARP1 and SET. SET, a histone chaperone, is a general factor required for transcription from chromatin templates. PARP1, by ADP-ribosylation of different components of chromatin, promotes nucleosome decondensation and facilitates access to the transcriptional machinery (Gamble and Fisher, 2007). However, by forming complexes with the different regulators of transcription of specific genes, PARP1 can modulate gene expression in different ways. A transcription repressor, DEK, antagonizes the activity of SET in the facilitation of transcription. DEK is also covalently modified by PARP. Part of the transcription-facilitating activity of SET is due to the dislodging of DEK and PARP to allow the recruitment of RNA Polymerase II and the mediator complex. SET is also a regulator of the cell cycle and, as such, may exercise oncogenic effects (Canela et al., 2003). Loss of PARP1 induces lethality of BRCA1-deficient cells implying the role of PARP1 inhibitors in the treatment of breast cancer (Wang et al., 2007). Other chromatin-related proteins are HPIBP3 and the histone-binding protein NASP, which is involved in transporting histones into the nucleus of dividing cells. In addition, there were a few proteins involved in mRNA processing, such as La protein, which binds to poly(U) elements and participates in the maturation of transcripts (Kotik-Kogan et al., 2008); the 68 kDa subunit of the cleavage factor responsible for cleavage and polyadenylation of original transcripts (Brown and Gilmartin, 2003); and NHP2L1 protein, which is an integral part of the spliceosome. Overall, Egln1-knockdown-induced repression of all of these chromatin- and RNA-associated proteins implies an ability to inhibit the transcription and processing of mRNA. This effect is potentially compatible with the lack of an effect of Egln1 knockdown on RNA polymerase II in VHL(−) cells. It further implies that hydroxylation and phosphorylation of Rpb1 caused by Egln1 knockdown in VHL(+) cells may protect these proteins from downregulation.

Another interesting group of proteins reduced by Egln knockdown in VHL(−) cells are three proteins with hydroxylase activity: disulfide isomerase or subunit beta of the collagen prolyl hydroxylase, lysyl hydroxylase, and aspartyl hydroxylase. Of those, aspartyl hydroxylase plays a role in the oncogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma (Xian et al., 2006). Both lysyl and aspartyl hydroxylases utilize alpha-ketoglutarate and Fe(II) for their hydroxylating activity. The beta subunit of prolyl hydroxylase has disulfide isomerase activity, while another subunit, alpha, has the true prolyl hydroxylase activity. Clearly, all of these enzymes belong to a family of ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases similar to Egln2, and our observation implies that they can exercise control over each other’s expression. The molecular mechanism of such regulation remains to be determined.

Finally, the expression of one protein, calrecticulin, was similarly reduced by Egln1 knockdown in both VHL(+) and VHL(−) cells. Calrecticulin directly interacts with MHC proteins, as well as with integrins ITGB2B and ITGB3, and with von Willebrand factor (Rizvi et al., 2004). It has also been implicated in lupus erythematosus. At the same time, calrecticulin interacts with mRNA GCN motifs in C/EBP, inhibiting its translation (Timchenko et al., 2002). Calrecticulin is associated with cancer. Together with calnexin, calrecticulin helps in the assembly of MHC I-type proteins (Sadasivan et al., 1996). Although calrecticulin appears to associate with T-cell antigen proteins differently than does calnexin, which is downregulated in metastatic melanomas, downregulation of calrecticulin could also contribute to the failure of the immune system to control tumor progression (Dissemond et al., 2004). However inhibition of calrecticulin appears to be mediated by the effects of Egln1 knockdown that do not affect RNA polymerase or HIF.

The data presented above demonstrate that knockdown of Egln1 has very different effects on protein expression in VHL(+) cells, as compared to VHL(−) cells. Perhaps the most striking difference is that we did not detect the induction of any protein factors upon Egln1 knockdown in VHL(+) cells, but we did measure the fairly substantial overexpression of several mitochondrial proteins, including several subunits of ATP synthase, in VHL(−) cells. Another important observation presented here is that, in VHL(−) cells, knockdown of Egln1 was associated with repression of several proteins that are associated with RNA Polymerase function. This is possibly related to the observation that knockdown of Egln1 in VHL(+) cells affects the activity of Rpb1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the following grants: NCI CA122346, DoD W81XWH-07-02-0026. We thank Dr. M. Daston for editing the manuscript and Glenn Doerman for preparation of the tables.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen S, Abuzenadah AM, Hinks J, Blagg JL, Gursel T, Ingerslev J, Goodeve AC, Peake IR, Daly ME. A novel von Willebrand disease-causing mutation (Arg273Trp) in the von Willebrand factor propeptide that results in defective multimerization and secretion. Blood. 2000;15:560–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelhoff RJ, Tian Y-M, Raval RR, Turley H, Harris AL, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Gleadle JM. Differential function of the prolyl hydroxylase PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3 in the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38458–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragones J, Schneider M, Van Geyte K, Fraisl P, Dresselaers T, Mazzone M, Dirkx R, Zacchigna S, Lemieux H, Jeoung NH, Lambrechts D, Bishop T, Lafuste P, Diez-Juan A, Harten SK, Van Noten P, De Bock K, Willam C, Tjwa M, Grosfeld A, Navet R, Moons L, Vandendriessche T, Deroose C, Wijeyekoon B, Nuyts J, Jordan B, Silasi-Mansat R, Lupu F, Dewerchin M, Pugh C, Salmon P, Mortelmans L, Gallez B, Gorus F, Buyse J, Sluse F, Harris RA, Gnaiger E, Hespel P, Van Hecke P, Schuit F, Van Veldhoven P, Ratcliffe P, Baes M, Maxwell P, Carmeliet P, et al. Deficiency or inhibition of oxygen sensor PHD1 induces hypoxia tolerance by reprogramming basal metabolism. Nature Gen. 2008;40:170–80. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma K, Yanagida-Asanuma E, Faul C, Tomino Y, Kim K, Mundel P. Synaptopodin orchestrates actin organization and cell motility via regulation of RhA signaling. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:485–91. doi: 10.1038/ncb1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berra E, Benizri E, Ginouves A, Volmat V, Roux D, Pouyssegur J. HIF prolyl hydroxylase 2 is the key oxygen sensor setting low steady-state levels of HIF-1 alpha in normoxia. EMBO J. 2003;22:4082–90. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KM, Gilmartin GM. A mechanism for the regulation of pre-mRNA 3′ processing by human cleavage factor. Im Mol Cell. 2003;12:1467–76. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00453-2. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnelle JK, Bell EL, Quaseda NM, Vercautern K, Tiranti V, Zeviani M, Scarpulla RC, Chandel NS. Oxygen sensing requires mitochondrial ROS but not oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metabol. 2005;1:409–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canela N, Rodriguez-Vilarrupla A, Estanyol JM, Diaz C, Pujol MJ, Agell N, Bachs O. The SET protein regulates G2/M transition by modulating cyclin B-dpenendent kinase 1 activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1158–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207497200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter B, Hill KJ, Charalambous M, Wagner KJ, Lahiri D, James DI, Andersen JS, Schumacher V, Royer-Pokora B, Mann M, Ward A, Roberts SG. 2004 BASP1 is a transcriptional corepressor for the Wilms’ tumor suppressor protein WT1. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:537–49. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.2.537-549.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevrollier A, Loiseau D, Chabi B, Renier G, Douay O, Malthiery Y, Stepien G. ANT2 isoform is required for cancer glycolysis. J Bioenerg Biomemebr. 2005;37:307–16. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-8642-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins EP, Berra E, Comerford KM, Ginouves A, Fitzgerald KT, Seeballuck F, Godson C, Nielsen JE, Moynagh P, Pouyssegur J, Taylor CT. Prolyl hydroxylase-1 negatively regulates IkB kinase -b, giving insight into hypoxia-induced NF-kB activity. PNAS USA. 2006;103:18154–59. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602235103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissemond J, Busch M, Kothen T, Mors J, Weimann TK, Lindeke A, Goos M, Wagner SN. Differential downregulation of endoplasmic reticulum-residing chaperones calnexin and calreticulin in human metastatic melanoma. Cancer Lett. 2004;203:225–31. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein AC, Gleadle JM, McNeill LA, Hewitson KS, O’Rourke J, Mole DR, Mukherji M, Metzen E, Wilson MI, Dhanda A, Tian YM, Masson N, Hamilton DL, Jaakkola P, Barstead R, Hodgkin J, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Schofield CJ, Ratcliffe PJ. C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell. 2001;107:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing RM, Chu P, Elisma F, Li H, Taylor P, Climie S, McBroom-Cerajewski L, Robinson MD, O’Connor L, Li M, Taylor R, Dharsee M, Ho Y, Heilbut A, Moore L, Zhang S, Ornatsky O, Bukhman YV, Ethier M, Sheng Y, Vasilescu J, Abu-Farha M, Lambert JP, Duewel HS, Stewart II, Kuehl B, Hogue K, Colwill K, Gladwish K, Muskat B, Kinach R, Adams SL, Moran MF, Morin GB, Topaloglou T, Figeys D. Mapping of human protein-protein interactions by mass spectrometry. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:89. doi: 10.1038/msb4100134. Large-scale m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong G-H, Takeda K. Role of regulation of prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins. Cell Death Diff. 2008;15:635–41. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei C, Edgar BA. Drosophila cyclin D/Cdk4 requires HIf-1 prolyl hydroxylase to drive cell growth. Dev Cell. 2004;6:241–51. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00409-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble MJ, Fisher RP. SET and PARP1 remove DEK from chromatin to permit access by the transcription machinery. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;2007;14:548–55. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerald D, Berra E, Frapart YM, Chan DA, Giaccia AJ, Mansuy D, Pouyssegur J, Yaniv M, Mechta-Grigoriou F. JunD reduces tumor angiogenesis by protecting cells from oxidative stress. Cell. 2004;118:781–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gygi SP, Rist B, Gerber SA, Turecek F, Gelb MH, Aebersold R. Quantitative analysis of complex protein mixtures using isotope-coded affinity tags. Nature Biotechnology. 1999;17:994–99. doi: 10.1038/13690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiman CA, Setiawan VW, Xia LY, Le Marchand L, Ingles SA, Ursin G, Press MF, Bernstein L, John EM, Henderson BE. A variant in the cytochrome p450 oxidoreductase gene is associated with breast cancer rist in African Americans. Cancer Res. 2007;67:565–68. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horke S, Witte I, Wigenbus P, Kruger M, Strand D, Forstermann U. Paraoxanase-2 reduces oxidative stress in vascular cells and decreases endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced caspase activation. Circulation. 2007;17:2055–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.681700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga EG, Tsuji S, Romijn RA, Schiphorst ME, de Groot PG, Sixman JJ, Gros P. Structure of glycoprotein Ibalpha and its complex with von Willebrand factor A1 domain. Science. 2002;297:1176–79. doi: 10.1126/science.107355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivan M, Kondo K, Yang H, Kim W, Valiando J, Ohh M, Salic A, Asara JM, Lane WS, Kaelin WG., Jr HIF-alpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science. 2001;292:464–68. doi: 10.1126/science.1059817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gilbert J, Gaskell SJ, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science. 2001;292:468–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1059796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG., Jr Proline hydroxylation and gene expression. Ann Rev Biochem. 2005;74:115–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotik-Kogan O, Valentine ER, Sanfelice D, Conte MR, Curry S. Structural analysis reveals conformational plasticity in the recognition of RNA 3′ ends by the human La protein. Structure. 2008;16:852–62. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova AV, Meller J, Schnell PO, Nash JA, Ignacak ML, Sanchez Y, Conaway JW, Conaway RC, Czyzyk-Krzeska MF. von Hippel-Lindau protein binds hyperphosphorylated large subunit of RNA polymerase II through a proline hydroxylation motif and targets it for ubiquitination. PNAS USA. 2003;100:2706–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0436037100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Nakamura E, Yang H, Wei W, Linggi MS, Sajan MP, Farese RV, Freeman RS, Carter BD, Kaelin WG, Jr, Schlisio S. Neuronal apoptosis linked to Egln3 prolyl hydroxylase and familial pheochromocytoma genes:developmental culling and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:155–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhaylova O, Ignacak ML, Barankiewicz TJ, Harbaugh SV, Yi Y, Maxwell PH, Schneider M, Van Geyte K, Carmeliet P, Revelo MP, Wyder M, Greis KD, Meller J, Czyzyk-Krzeska MF. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein and Egl 9-type proline hydroxylases regulate the large subunit of RNA Polymerase II in response to oxidative stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2701–17. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01231-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Frew IJ, Hagensen M, Skals M, Habelhah H, Bohumik A, Kadoya T, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Frapell PB, Bowtell DD, Ronai Z. Siah2 regulates stability of prolyl-hydroxylases, controls HIF1alpha abundance, and modulates physiological responses to hypoxia. Cell. 2004;117:941–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi SM, Mancino L, Thammavongsa V, Cantley RL, Raghavan M. A polypeptide binding conformation of calreticulin is induced by heat shock, calcium depletion or by deletion of the C-terminal acidic region. Mol Cell. 2004;15:913–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross PL, Huang YN, Marchese JN, Williamson B, Parker K, Hattan S, Khainovski N, Pillai S, Dey S, Daniels S, Purkayastha S, Juhasz P, Martin S, Bartlet-Jones M, He F, Jacobson A, Pappin DJ. Multiplexed protein quantitation in saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Mol Cell Proteom. 2004;3:1154–69. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400129-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadasivan B, Lehner PJ, Spies T, Cresswell P. Role of calreticulin and a novel glycoprotein, tapsin, in the interaction of MHC class I molecules with ATP. Immunity. 1996;5:103–14. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80487-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timchenko LT, Iakova P, Welm AL, Cai ZJ, Timchenko NA. 2002 calreticulin interacts with C/EBPalpha and C/EBPbeta mRNAs and represes translation of C/EBP proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7242–57. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7242-7257.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya H, Iseda T, Hino O. Identification of a novel protein (VBP-1) binding to the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor gene product. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2881–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Flier A, Kuikman I, Kramer D, Geerts D, Kreft M, Takafuta T, Shapiro SS, Sonnenberg A. Different splice variants of filamin B affect myogenesis, subcellular distribution, and determine binding of integrin (beta) subunits. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:361–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Liu L, Montagna C, Ried T, Deng CX. Haploinsufficiency of PARP1 accelerates Brca1-associated centrosome amplification, telomere shortening, genetic instability, apoptosis, and embryonic lethality. Cell Death Diff. 2007;14:924–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson D, Pikovski I, Cranmer SL, Mangin P, Mistry N, Domagala T, Chehab S, Lanza F, Salem HH, Jackson SP. Interaction between platelet glycoprotein Ibalapha and filamin-1 is essential for glycoprotein Ib/IX anchorage at high shear. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2151–59. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian ZH, Zhang SH, Cong WM, Yan HX, Wang K, Wu MC. Expression of aspartyl beta hydroxylase and its clinicopathological significance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:280–86. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Cheng W, Hong L, Chen W, Wang Y, Lin S, Han J, Zhou H, Gu J. Adenine nucleotide (ADP/ATP) translocase 3 participates in the tumor necrosis factor induced apoptosis of MCF-7 cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;18:4681–89. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-12-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshio T, Morita T, Kimura Y, Tsujii M, Hayashi N, Sobue K. Caldesmon suppresses cancer cell invasion by regulating podosome/invaopodium formation. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3777–82. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]