Abstract

This study examined the impact of parental modeled behavior and permissibility of alcohol use in late high school on the alcohol use and experienced negative drinking consequences of college students. Two-hundred ninety college freshmen at a large university were assessed for perceptions of their parents’ permissibility of alcohol use, parents’ alcohol-related behavior, and own experienced negative consequences associated with alcohol use. Results indicate that parental permissibility of alcohol use is a consistent predictor of teen drinking behaviors, which was strongly associated with experienced negative consequences. Parental modeled use of alcohol was also found to be a risk factor, with significant differences being seen across the gender of the parents and teens. Discussion focuses on risk factors and avenues for prevention research.

Keywords: Parenting, alcohol use, college

1 Introduction

It has been argued that alcohol currently poses the greatest risk to the health of US college students (Hingson, Heeren, Winter & Wechsler, 2005; Hingson, Heeren, Zakos, Kopstein, & Wechsler, 2002; NIAAA, 2006). In a national study, 87% of college students have reported trying alcohol and 40% have reported heavy episodic drinking (commonly defined as consuming 5 or more drinks in a row for men and 4 or more drinks in a row for women) at least once during the prior two week period (Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2006). Compared to their non-college-attending peers, research indicates that American college students drink more heavily per occasion and are more likely to receive a diagnosis of DSM-IV alcohol abuse (O’Malley & Johnson, 2002; Slutske, 2005). Given these findings, it is clear that alcohol use and abuse in college settings is a serious public health problem, as heavy drinking in college has long been recognized as a contributing factor to many other problems among college students (e.g., driving drunk, physical fights, or alcohol related arrests) (Hingson et al., 2005; 2002).

A wealth of research has shown that heavy drinking in college has been associated with academic impairment; psychological problems; high-risk sexual behaviors; verbal, physical, and sexual violence; personal injuries or death; property damage; and legal costs (Baer, 1994; Larimer, Irvine, Kilmer, & Marlatt, 1997; Read, Wood, Davidoff, McLacken, & Campbell, 2002; Sher, Bartholow, & Nanda, 2001; Wechsler et al., 2002). Experiencing these consequences not only impact students negatively, but universities and communities as well. National estimates of alcohol related unintentional injury deaths range from 1,600 to 1,700 per year (Hingson et al., 2005). Further, in a national survey, college administrators estimated that 30% of the time alcohol was involved in student attrition (Anderson & Gadaleto, 2001).

Many of these experienced consequences have been shown to vary across student gender. For example, Park and Grant (2005) found that men and women differed in their experience of some consequences, citing that heavy alcohol consumption was generally more strongly related to consequences for women than for men. In 2005, Murphy and colleagues found that alcohol misuse was associated with diminished satisfaction across social, school, relationship, family, and future domains among women but only diminished social and school satisfaction among men. In addition, Leinfelt and Thompson (2004) found that being male was among a list of common attributes that increased one’s likelihood of experiencing an alcohol related arrest. Collectively, these findings highlight the necessity of exploring potential gender differences when examining alcohol-related negative consequences in college.

In an attempt to reduce alcohol use and experienced negative consequences during this developmental period, a wealth of research has explored potential targets of substance use intervention at the college level (Arnett, 2005; Baer & Carney, 1993; Larimer et al., 1997; Turrisi, Jaccard, Taki, Dunnam, & Grimes, 2001; Wagenaar, Toomey, & Lenk, 2004). Four major categories represent the focus of this work, these are: individual factors, ecological factors, peer influences, and parental influences (Baer, 2002; Hawkins, Miller, & Catalano, 1992). Although past research has indicated that parental influence diminishes as adolescents transition into college, a growing literature over the last 15 years suggests that parents maintain influence on their teen as they transition into college across numerous domains (American College Health Association, 2003; Amerikaner, Monks, Wolfe, & Thomas, 1994; Galotti, & Mark, 1994; Kashubeck, & Christensen, 1995; Lehr, DiIorio, Dudley, & Lipana, 2000). In addition, a substantial body of literature has underscored the importance of parental involvement in adolescent substance use, even among those in late adolescence or early adulthood (Abar & Turrisi, 2008; Duncan, Duncan, & Hops, 1994; Reifman et al., 1998; Turrisi, Wiersma, & Hughes, 2000; Turrisi et al., 2001; Windle, 2000; Wood, Read, Mitchell, & Brand, 2004).

From this research, various associations have been drawn regarding parental influence on college teen alcohol use and related behaviors including parent communication about alcohol, parental monitoring, knowledge of teen behaviors, and influence on teen friend choice in college (Abar & Turrisi, 2008; Turrisi et al., 2001; Wood et al., 2004). The impact of parental permissibility of alcohol use on college alcohol use and experienced negative consequences has not yet been examined among teens transitioning into college. This remains an important concept to explore as it stands to reason that parenting develops as adolescents develop. Our data show that as adolescents mature into their senior year of high school, parents begin to feel more comfortable about permitting them to drink alcohol underage. It remains unknown whether this permissibility of alcohol use is potentially harmful or beneficial in regard to experienced negative consequences due to alcohol use in college.

Literature on parental modeling of alcohol use indicates that alcohol modeling is associated with more risky alcohol outcomes for adolescents (Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Hawkins et al., 1997; Latendresse et al., 2008; White, Johnson, & Buyske, 2000). This current study attempts to extend this work by exploring whether parental modeling of alcohol use is associated with college alcohol use and associated consequences when also accounting for parental permissibility for alcohol use in high school. In addition, this study will examine the influence of a range of parental alcohol modeling (low to high levels of use) on teen behavior. Examining the influence of modeling low alcohol use is potentially important, as it is more statistically common than parental models of heavy use and the prospective impact on college alcohol use and experienced consequences is currently unknown.

In addition to the need for research exploring the impact of parent permissibility and modeling of alcohol use on college use and experienced consequences, previous studies examining parental influence on college alcohol use and related consequences remain somewhat limited as much of the work examining the associations between parental influence, teens, and risk behaviors tend to focus solely on mothers and their interactions with their teen, rather than studying both parents (Abar & Turrisi, 2008; Guilamo-Ramos, Jaccard, Turrisi, Johansson, & Bouris, 2006; Turrisi et al., 2000). Although mothers have been found to be influential on college teens through the formation of attitudes and beliefs about substance use, engagement in substance use, choice of substance using friends, and engagement in alternative activities (Abar & Turrisi, 2008; Turrisi et al., 2001; 2000), research in this area is incomplete without an examination of the impact of paternal behaviors as well. This study sought to further advance the literature on parental influence on college alcohol use by exploring the influence of modeled behavior and permissibility of alcohol use of both mothers and fathers on the experienced negative drinking consequences of college students.

Due to this previously mentioned lack of evidence, there remains some debate as to whether or not permitting underage drinking or modeling responsible adult drinking in the home might foster more safe and responsible young drinkers in college (Wagenaar & Toomey, 2002). It is currently unclear the degree to which behaviors engaged in and observed in the home generalize to settings outside the home. In an effort to inform a parent-based intervention designed to reduce the onset and extent of college drinking and its associated negative consequences, the following research aims were addressed in a cross-sectional study: (a) researchers examined the extent to which both parent permissibility of alcohol use and modeled parent drinking behavior are associated with teen drinking behaviors and negative consequences experienced in college in order to explore potential benefits and risks of particular parenting practices; (b) researchers explored potential differences in the impact of permissibility and modeled behavior on these behaviors by parent gender and teen gender. To the authors’ knowledge, no college drinking literature has yet explored how both mothers’ and fathers’ drinking behavior and permissibility of alcohol use influences teen use and experienced negative consequences associated with alcohol use in college in the same study.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

As part of a larger study, a random sample of 500 students was recruited from the freshman class at a large, northeastern, public university and invited to complete a survey regarding alcohol use and related behaviors. Two follow-up emails were sent to the 500 freshmen in an effort to increase participation. Three-hundred freshmen initially consented to participate. Two-hundred and ninety (58% response rate) freshmen of the original sample completed the entire survey. This response rate is consistent with others using a web-based approach (Larimer et al., 2007; McCabe et al., 2002; McCabe et al., 2005; Thombs, et al., 2005). In order to participate in the study, students had to have been at least 18 years of age at the time of recruitment (M = 18.6 years, SD = .50). Roughly 61% of the sample was female (n = 176). The majority of students were self-identified as White/Caucasian (88.9%), and nearly everyone resided in a residence hall (97.2%). In terms of socioeconomic status, 53% of participants perceived their family’s status to be about average and 37% felt their family SES was moderately higher than most families.

2.2 Procedure

Potential participants were contacted via email regarding the opportunity to participate in an online survey regarding student drinking behaviors and parent-teen communication. The survey was designed to take about 30 to 40 minutes to complete, and students were given $10 for completing the survey. Students provided informed consent before beginning the online survey.

2.3 Measures

Parent permissibility. Two aspects of parent permissibility were examined in the current study. The first aspect, parent limit setting, was indexed by a single item asking “During your senior year of high school, how many drinks would your parents consider to be the upper limit for you to consume on any given occasion (7 point scale; no amount would be ok, 1 drink, 2 drinks, 3 drinks, 4 drinks, 5 drinks, 6 to 12 drinks, and there was no upper limit)?” The second aspect of permissibility examined were student perceptions of parental acceptability of alcohol use. Both maternal and paternal acceptability were measured. Items were on a 5 point scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”, and were as follows: “My mother/father thinks it is okay if I drink alcohol on special occasions outside the home” (e.g., at a friend's party), “my mother/father doesn't mind if I drink alcohol once in a while”, and “my mother/father disapproves of me drinking alcohol under any circumstances (reverse coded).” These items were internally consistent for both mothers (Cronbach’s α =.87) and fathers (Cronbach’s α =.87) and were summed to represent maternal and paternal acceptability, respectively. The bivariate correlations between limit-setting and maternal and paternal acceptability were .56 and .49, respectively. These associations indicate a moderate to strong relationship between the two measures of permissibility, but magnitudes of this size indicate substantial uniqueness exists for each of the measures.

Parent modeled behavior. Students provided retrospective data regarding the alcohol related behaviors of mothers, fathers, and their parents in general. Parent specific items were as follows: “How often do you think your mother/father drank alcohol in the past year (8 point scale; 0 = not at all, 1 = 1 to 5 times a year, 3 = about once a month, 6 = 3 to 4 times a week, 8 = everyday)?” and “In the past year, how many drinks do you think your mother/father had per drinking occasion (8 point scale; 0 = 0 drinks, 1 = 1 drink, 5 = 5 drinks, 7 = 7 or 8 drinks, 8 = 9 or more drinks)?”. These items, representing frequency and quantity of alcohol use, were multiplied to provide indices of maternal and paternal drinking that capture each of these facets of behavior. General parent modeled behavior items asked “While growing up, how often was alcohol on the dinner table (6 point scale; 0 = never, 3 = once a week, 5 = nearly everyday)?”, “While growing up, how often did you see your parents drink alcohol (8 point scale; 0 = not at all, 1 = 1 to 5 times a year, 3 = about once a month, 6 = 3 to 4 times a week, 8 = everyday)?”, and “While growing up, how often did you see your parents drunk from alcohol (8 point scale; 0 = not at all, 1 = 1 to 5 times a year, 3 = about once a month, 6 = 3 to 4 times a week, 8 = everyday)?”. These items exhibited were internally consistent (Cronbach’s α =.70) and summed to create a composite representing the family alcohol environment.

Teen drinking behaviors. Three indices of teen drinking were assessed. Weekend drinking was represented by the sum of two items: “How many drinks do you have on a typical Friday?” and “How many drinks do you have on a typical Saturday?” (r = .93, p < .001). Peak drinking was represented by a single item asking, “Think of the occasion when you drank the most in the past month. How much did you drink?” Teen frequency of drunkenness was indexed by a single item asking, “During the past month, how many times have you gotten drunk, or very high from alcohol?” which was measured on a 6 point scale (Never, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, 7–8, and 9 or more times).

Negative consequences of alcohol use. A subset of 26 items from the Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (YAAPST, Hurlbut & Sher, 1992) pertaining specifically to negative consequences of one’s own use was taken (Cronbach’s α =.88). Participants responded about the frequency of occurrence, in the past year, of the specific consequences measured (For a complete list, see Appendix A).

2.4 Plan of analyses

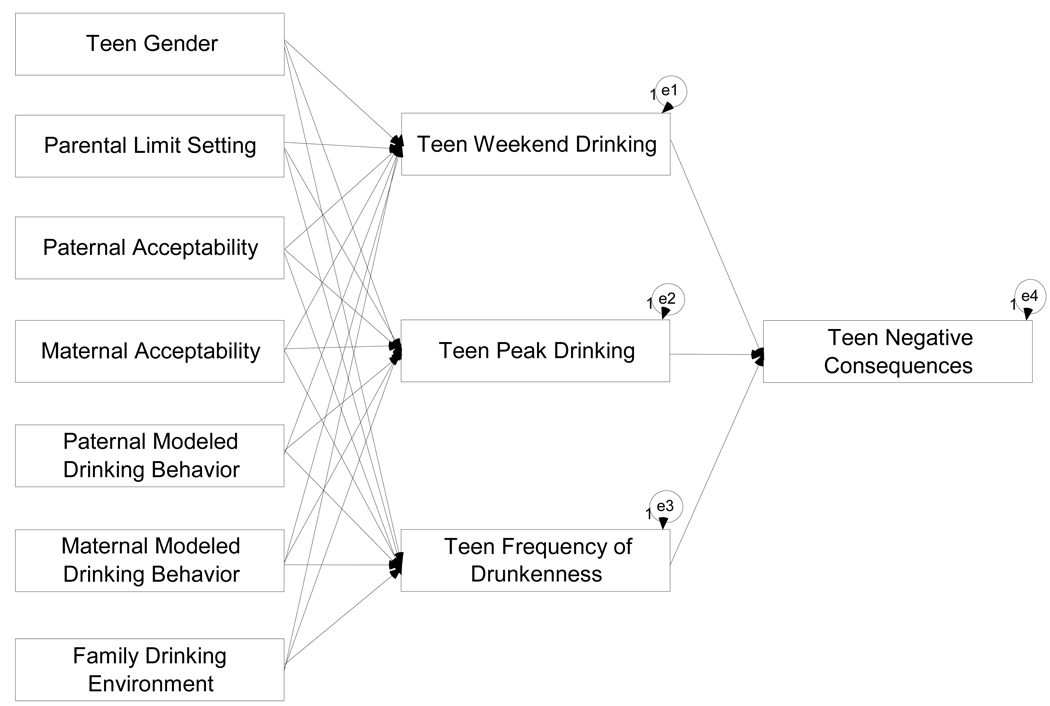

A saturated, manifest structural equations model was run using AMOS 7.0. Because the model was saturated, the unstandardized β weights reported are equivalent to those that would have been found had a series of multiple regressions been performed. Parent permissibility, parent modeled behavior, and teen gender (coded women = 0; man = 1) were used to predict teen drinking behaviors, which predicted teen experienced negative consequences associated with alcohol use (see Figure 1 for illustrative model). The predictor variables were centered in order to reduce non-essential collinearity. All residual direct effects (e.g., paternal acceptability predicting teen negative consequences) were modeled, as were all gender by parent characteristics interactions. These interaction terms were included in order to explore whether or not specific aspects of parenting were more strongly associated with experienced negative consequences for a given gender. These interactions also allowed researchers to examine the extent to which the effects of same sex modeling or permissibility (e.g. fathers and sons) differ from the effects of opposite sex modeling or permissibility (e.g. fathers and daughters).

Figure 1. Manifest structural equation mode.

Note: The tested model was saturated, with all residual direct effects of parenting characteristics on teen negative consequences, interaction terms on teen drinking and negative consequences, covariances between parenting characteristics, and residual covariances between teen drinking variables being modeled. These associations were left out of the figure in the interest of parsimony.

3 Results

Preliminary results showed that students, on average, tend to report consuming 9.14 alcoholic drinks (SD = 7.98), with men averaging 12.52 (SD = 9.74) and women averaging 6.96 (SD = 5.67). The average peak number of drinks consumed was over 7 drinks (M = 7.04, SD = 5.77), with men reporting a peak of 9.46 (SD = 6.66) and women averaging 5.50 (SD = 4.52). In terms of frequency of drunkenness, the average number of occurrences was 1.86 (SD = 1.65), with men and women reporting very similar frequencies (Mmen = 1.98, SD = 1.64; Mwomen = 1.78, SD = 1.66). Lastly, the average negative consequences score was 18.90 (SD = 16.44). Male students report an average of 23.32 (SD = 19.83), while female students average 16.08 (SD = 13.16).

Results indicate that the only significant predictors of teen drinking behaviors in college were gender and parental limit setting (see Table 1). Men report significantly greater weekend drinking (β = 3.59, p < .001) and peak drinking (β = 2.68, p < .001). The greater the number of drinks parents set as a limit during high school, the more teens tend to report drinking on the weekend (β = 1.30, p < .001), the greater the peak number of drinks teens report consuming (β = 1.00, p < .001), and the more frequent teens report being drunk (β = .36, p < .001). In regard to predicting teen negative consequences associated with alcohol use, teen peak drinking, teen frequency of drunkenness, and paternal acceptability emerged as the only significant main effects. The greater the number of drinks consumed during peak episodes and the greater the frequency of teen drunkenness, the greater the experienced negative consequences associated with drinking in college (β = .95, p < .001 and β = 2.96, p < .001, respectively). Finally, the greater the perceived paternal acceptability, the fewer negative consequences teens tend to experience (β = −.61, p < .05).

Table 1.

Unstandardized β weights and SE’s predicting teen drinking and teen negative consequences

| Teen Weekend Drinking (r2 = .27) |

Teen Peak Drinking (r2 = .25) |

Teen Frequency of Drunkenness (r2 = .20) |

Teen Negative Consequences (r2 = .59) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teen Gender | 3.59*** | 2.68*** | −.20 | 1.17 |

| (.90) | (.65) | (.19) | (1.52) | |

| Parental Limit Setting | 1.30*** | 1.00*** | .36*** | .48 |

| (.32) | (.24) | (.07) | (.53) | |

| Paternal Acceptability | .21 | .09 | .02 | −.61* |

| (.18) | (.13) | (.04) | (.28) | |

| Maternal Acceptability | −.13 | −.05 | −.04 | −.01 |

| (.18) | (.13) | (.04) | (.27) | |

| Paternal Modeled | .08 | .04 | .02 | .10 |

| Drinking Behavior | (.05) | (.04) | (.01) | (.07) |

| Maternal Modeled | .09 | .03 | .02 | −.09 |

| Drinking Behavior | (.08) | (.06) | (.02) | (.12) |

| Family Drinking | −.24 | −.14 | −.06 | .30 |

| Environment | (.15) | (.11) | (.03) | (.24) |

| Teen Weekend | --- | --- | --- | .29 |

| Drinking | (.18) | |||

| Teen Peak Drinking | --- | --- | --- | .95*** |

| (.22) | ||||

| Teen Frequency of | --- | --- | --- | 2.96*** |

| Drunkenness | (.66) |

p <.05

p < .01

p < .001

In addition to the main effects discussed above, results revealed three significant interactions by gender predicting teen negative consequences. The effect of paternal acceptability differed by gender, such that it high level of paternal acceptability appears to function as a weak protective factor for male students and as a moderate risk factor for female students, β = −1.33, p < .05. The effect of maternal modeled drinking behavior also differed by gender, such that maternal drinking is riskier for women, β = − .48, p < .05. Lastly, the impact of one’s family drinking environment on experienced negative consequences was shown to be a significant risk factor only for male students, β = 1.34, p < .01.

Given the consistent associations between limit setting and teen drinking, additional analyses were performed in order to provide a more complete understanding of these relationships. Parental limit setting was recoded into a dichotomous variable, with 0 representing “no amount would be ok” and 1 representing “1 or more drinks.” This was done to examine whether or not an absolute limit, indicating complete disapproval, would result in different outcomes than any other limit set. Results indicate that parents who did not allow any drinking in high school tended to have teens who, in college, drank less on the weekends (M diff = −4.99, t (254) = −5.14, p < .001), had lower peak drinking (M diff = −3.56, t (256) = −5.10, p < .001), and had a lower frequency of drunkenness (M diff = −1.08, t (256) = −5.51, p < .001). These teens also tended to experience fewer negative consequences, M diff = −10.10, t (256) = −5.03, p < .001.

4. Discussion

The current study sought to examine the extent to which parental permissibility of alcohol use and modeled drinking behavior in high school predicted teen alcohol use and experienced negative consequences in college. Overall, results indicated that a parents’ permissive attitude toward alcohol use in late high school was a significant risk factor for teen alcohol misuse and associated consequences in college. Specifically, it appears that the limits parents set for their teens with regard to alcohol consumption are particularly important. Parents in this study who permitted relatively high levels of teen drinking in high school were more likely to have children who engaged in much riskier drinking behaviors than children whose parents permitted relatively low levels of teen drinking. This result appears to be fairly robust, as it was found even after accounting for the effects of gender and all other measured parenting characteristics. It is important to note that limit setting was shown to be important for both male and female college students. Further, the results of additional analyses on limit setting unequivocally showed that complete disapproval was more protective than approving of alcohol consumption at any level, as students with more permissive parents drank significantly more and experienced significantly more negative consequences associated with alcohol consumption.

In reference to recent pieces in the NY Times and Time Magazine (Asimov, 2008; Cloud, 2008), supporting parental endorsement of alcohol use in the home, findings from the current study do not support the notion that parental permissibility of alcohol use (even in small supervised amounts) is likely to reduce later (college) misuse. Proponents of the media created “European Drinking Model” believe that, by allowing their adolescents to drink in controlled environments, their teens will experience fewer negative consequences as the result of use during college. This approach is believed to remove the mystique of the forbidden fruit (alcohol use), thereby erasing the likelihood of misuse once exposed and away from parents. The current study found that parent permissibility was associated with higher drinking rates and experienced consequences for college teens than a strict policy of no underage use.

Results also indicated that parental modeling behaviors involving alcohol use are influential on the future alcohol use and related negative consequences one’s teen experiences in college. It appears that the maternal drinking is a risk factor for female college students, and the family drinking environment appears to be a risk factor for men. These findings support previous research noting that high levels of parental alcohol consumption can be a risk factor for later teen alcohol related outcomes (Hawkins et al., 1992; Hawkins et al., 1997). Future research should examine more closely the effects of the specific modeling of responsible drinking behaviors on later teen outcomes. In addition, it remains possible that the association between modeling alcohol in the home and negative college outcomes may differ based on personality, socio-emotional, and/or intellectual characteristics of the teen. Additional work should continue to examine potentially individual teen characteristics that might moderate this relationship between modeling and college alcohol related outcomes.

In reference to teen gender, although several differences were illustrated across gender, it does not appear that children exclusively model the behaviors of same sex parents. It is important to note that these findings represent first steps in the understanding of parent specific modeling of alcohol use at this age. Future work might benefit from taking a more fine-grained, perhaps person-centered, approach to the examination of same versus opposite sex parental modeling.

There were five general limitations of the current study. First, the analyses performed relied solely on the statistical significance of un-standardized beta weights in a cross-sectional structural equations model, limiting the causation that can be inferred. However, several of the associations examined imply a chronological ordering of events. For example, a number of the parental modeled behaviors and permissibility that students are retrospectively reporting (i.e. while growing up…) have taken place before the negative consequences reported (i.e. in the past year). This temporal sequencing provides a measure of causal support to the analyses performed. A second related limitation is that the data are retrospective in nature. While the items measured ask for estimates of relatively salient parental behaviors and have been published in the literature (Abar & Turrisi, 2008), it is possible that student recollection could be skewed, potentially due to living away from parents for at least part of the year. Future research should seek to incorporate parent responses regarding permissibility and modeled behavior. Third, due to limitations associated with sample size, the only interactions that were examined were between teen gender and parenting characteristics. It is possible that significant higher-order interactions exist among those parenting characteristics measured. Future work in this area may benefit from examining these issues with a larger sample using person-centered approaches, such as latent class or latent profile analysis. Fourth, the measure of limit setting for this study did not take into account sips or half drinks of alcohol, only full drinks. Future work should examine the potential influence of permitting sips /tastes of alcohol in comparison to full drinks on later use and consequences. Finally, the sample was relatively small, largely homogenous in regard to ethnicity (90% Caucasian), and was collected at a single university. It is important to replicate these findings with a larger, more diverse, and representative college sample, as parenting characteristics and behaviors may potentially have differential effects across ethnicity and college setting.

Conclusions and Future Directions

The current findings imply that, in order for parents to successfully reduce their teens’ potential alcohol related harm in college, they should be sensitive to the notion that the alcohol-related permissibility and modeled behavior may be influential. In particular, this study shows that acceptance of underage alcohol use in the home is likely to be an ineffective strategy to reduce the likelihood that one’s teen will misuse alcohol in college, while disapproval seems to produce the most optimal outcome in this regard. The idea that parents may decrease the chances of their teen misusing alcohol once in college by permitting underage use prior to college entrance is not supported by these data. Future prevention research with parents and teens may benefit from encouraging the communication of parental disapproval of alcohol use to teens until the age of 21.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant R01 AA 12529 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and grant T32 DA017629 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Appendix A

Negative consequences of alcohol use

Have you driven a car when you knew you had too much to drink to drive safely?

Have you had a headache (hangover) the morning after you had been drinking?

Have you felt very sick to your stomach or thrown up after drinking?

Have you showed up late for work or school because of drinking, a hangover, or an illness caused by drinking?

Have you gotten into physical fights when drinking?

Have you ever gotten into trouble at work or school because of drinking?

Have you ever been fired from a job or suspended or expelled from school because of your drinking?

Have you ever skipped an evening meal because you were drinking?

Have you become rude, obnoxious, or insulting after drinking?

Have you damaged property, set off a false alarm, or other things like that after you had been drinking?

Have you ever received a lower grade on an exam or paper than you should have because of drinking?

Have you ever been arrested for drunken driving, driving while intoxicated, or driving under the influence?

Have you ever been arrested, even for a few hours, because of other drunken behavior?

Has drinking ever gotten you into sexual situations which you later regretted?

Have you ever awakened the morning after a good bit of drinking and found that you could not remember a part of the evening before?

Have you ever had 'the shakes' after stopping or cutting down on drinking (for example, your hands shake so that your coffee rattles in the saucer or you have trouble lighting a cigarette)?

Have you ever felt like you needed a drink just after you'd gotten up (that is, before breakfast)?

Because you had been drinking, have you ever neglected to use birth control or neglected to protect yourself from sexually transmitted diseases?

Because you had been drinking, have you ever had sex when you didn't really want to?

Because you had been drinking, have you ever had sex with someone you wouldn't ordinarily have sex with?

Have you ever been pressured or forced to have sex with someone because you were too drunk to prevent it?

Have you ever pressured or forced someone to have sex with you after you had been drinking?

Have you ever felt guilty about your drinking?

Has your doctor ever told you that your drinking was harming your health?

Have you ever gone to anyone for help to control your drinking?

Have you ever attended a meeting of Alcoholics Anonymous because of concern about your drinking?

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abar C, Turrisi R. How important are parents during the college years? A longitudinal perspective of indirect influences parents yield on their college teens’ alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1360–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DS, Gadaleto AF. Results of the 2000 college alcohol survey: Comparison with 1997 results and baseline year. 2001 Retrieved May 23, 2005, from www.caph.gmu.edu/CAS/cas2000.pdf.

- American College Health Association. National Survey of College Students. ACHA. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Amerikaner M, Monks G, Wolfe P, Thomas S. Family interaction and individual psychological health. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1994;72:614–620. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35:235–253. [Google Scholar]

- Asimov E. Cans sips at home prevent binges? nytimes.com. 2008 March 26; Retrieved on September 22, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/26/dining/26pour.html.

- Baer JS. Student factors: Understanding individual variation in college drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14:40–53. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Effects of college residence on perceived norms for alcohol consumption: An examination of the first year in college. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994;8:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Carney MM. Biases in the perceptions of the consequences of alcohol use among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:54–60. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloud J. Should you drink with your kids? TIME Magazine. 2008 June 19;171(26) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Hops H. The effects of family cohesiveness and peer encouragement on the development of adolescent alcohol use: A cohort-sequential approach to the analysis of longitudinal data. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:588–599. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galotti KM, Mark MC. How do high school students structure an important life decision? A short-term longitudinal study of the college decision-making process. Research in Higher Education. 1994;35:589–607. [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Jaccard J, Turrisi R, Johansson M, Bouris A. Maternal perceptions of alcohol use by adolescents who drink alcohol. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:730–737. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grube J. Youth drinking rates and problems: A comparison of European countries and the United States. Calverton, MD: PIRE; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Graham JW, Maguin E, Abbott R, Hill KG, Catalano RF. Exploring the effects of age alcohol use initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:280–290. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibell B, Andersson B, Bjarnason T, Ahlstrom S, Balakireva O, Kokkevi A, Morgan M. The ESPAD report 2003: Alcohol and other drug use among students in 35 European countries. Stockholm: Swedish Council for Information on alcohol and Other Drugs; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related morality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Azkos R, Kopstein A, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:136–144. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, Sher KJ. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health. 1992;41:49–58. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-200. Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–45 (No. NIH Publication No. 06-5884) 2006

- Kashubeck S, Christensen SA. Parental alcohol use, family relationship quality, self-esteem, and depression in college students. Journal of College Student Development. 1995;36:431–443. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Irvine DL, Kilmer JR, Marlatt GA. College drinking and the Greek system: Examining the role of perceived norms for high-risk behavior. Journal of College Student Development. 1997;38:587–598. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Fabiano P, Stark C, Geisner IM, Mallett KA, Lostutter TW, Cronce JM, Feeney M, Neighbors C. Personalized mailed feedback for drinking prevention: One year outcomes from a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:285–293. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latendresse SJ, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J, Dick DM. Parenting mechanisms in links between parents' and adolescents' alcohol use behaviors. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:322–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehr ST, DiIorio C, Dudley WN, Lipana J. The relationship between parent-adolescent communication and safer sex behaviors in college students. Journal of Family Nursing. 2000;6:180–196. [Google Scholar]

- Leinfelt FH, Thompson KM. College-student drinking-related arrests in a college town. Journal of Substance Use. 2004;9:57–67. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Couper MP, Crawford S, D’Arcy H. Mode effects for collecting alcohol and other drug use data: Web and US mail. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:755–761. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick W, Boyd CJ. Assessment of difference in dimensions of sexual orientation: Implications for substance use research in a college-age population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:620–629. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, McDevitt-Murphy ME, Barnett N. Drink and be merry? Gender, life satisfaction, and alcohol consumption among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:184–191. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA. Initiative on underage drinking. 2006 Retrieved 9 November 2006, from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/AboutNIAAA/NIAAASponseredPrograms/underage.htm.

- O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002 Supplement No. 14:23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Grant C. Determinants of positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students: Alcohol use, gender, and psychological characteristics. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Davidoff OJ, McLacken J, Campbell JF. Making the transition from high school to college: The role of alcohol-related social influences factors in student’s drinking. Substance Abuse. 2002;23:53–65. doi: 10.1080/08897070209511474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifman A, Barnes G, Dintcheff BA, Farrell MP, Uhteg L. Parental and peer influences on the onset of heavier drinking among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:311–317. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Bartholow BD, Nanda S. Short- and long-term effects of fraternity and sorority membership on heavy drinking: A social norms perspective. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:42–51. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.15.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske W. Alcohol use disorders among US college students and their non-college-attending peers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:321–327. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, Ray-Tomasek J, Osborn CJ, Olds RS. The role of sex-specific normative beliefs in undergraduate alcohol use. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2005;29:342–351. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.29.4.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Jaccard J, Taki R, Dunnam H, Grimes J. Examination of the short-term efficacy of a parent intervention to reduce college student drinking tendencies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. Special Issue. 2001;15:366–372. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Wiersma KA, Hughes KK. Binge-drinking-related consequences in college students: Role of drinking beliefs and mother-teen communications. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:342–355. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar AC, Toomey TL. Effects of minimum drinking age laws: Review and analyses of the literature from 1960 to 2000. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Special Issue. 2002 Suppl14:206–225. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar AC, Toomey TL, Lenk KM. Environmental influences on young adult drinking. Alcohol Research and Health. 2004;28:230–235. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H, Johnson V, Buyske S. Parental modeling and parenting behavior effects on offspring alcohol and cigarette use: A growth curve analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;12:287–310. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. Parental, sibling, and peer influences on adolescent substance use and alcohol problems. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4:98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Read JP, Mitchell RE, Brand NH. Do parents still matter? Parent and peer influences on alcohol involvement among recent high school graduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:19–30. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]