Abstract

The three major immune disorders of the liver are autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Variant forms of these diseases are generally called overlap syndromes, although there has been no standardized definition. Patients with overlap syndromes present with both hepatitic and cholestatic serum liver tests and have histological features of AIH and PBC or PSC. The AIH-PBC overlap syndrome is the most common form, affecting almost 10% of adults with AIH or PBC. Single cases of AIH and autoimmune cholangitis (AMA-negative PBC) overlap syndrome have also been reported. The AIH-PSC overlap syndrome is predominantly found in children, adolescents and young adults with AIH or PSC. Interestingly, transitions from one autoimmune to another have also been reported in a minority of patients, especially transitions from PBC to AIH-PBC overlap syndrome. Overlap syndromes show a progressive course towards liver cirrhosis and liver failure without treatment. Therapy for overlap syndromes is empiric, since controlled trials are not available in these rare disorders. Anticholestatic therapy with ursodeoxycholic acid is usually combined with immunosuppressive therapy with corticosteroids and/or azathioprine in both AIH-PBC and AIH-PSC overlap syndromes. In end-stage disease, liver transplantation is the treatment of choice.

Keywords: Autoimmune hepatitis, Immunosuppressive agents, Primary biliary cirrhosis, Primary sclerosing cholangitis, Ursodeoxycholic acid

INTRODUCTION

The term “overlap syndrome” is used to describe variant forms of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) which present with characteristics of AIH and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) or primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Standardization of diagnostic criteria for overlap syndromes has not been achieved so far, since these disorders are uncommon. It remains unclear whether these overlap syndromes form distinct disease entities or are only variants of the major immune hepatopathies[1,2].

Overlap syndromes should always be considered once an autoimmune liver disease has been diagnosed[1]. Patients with overlap syndromes usually present with nonspecific symptoms, including fatigue, arthralgias, and myalgias. A hepatitic biochemical profile typically coexists with cholestatic laboratory changes[3,4]. Inter-estingly, transitions from one to another autoimmune hepatopathy have also been reported and are discussed together with the overlap syndromes[5,6]. Overlap of autoimmune cholangitis (AMA-negative PBC) and AIH has been described anecdotically and is discussed together with AIH-PBC overlap syndromes. Although combined features of both PBC and PSC have been reported in single cases[7], there is no clear evidence for the existence of an overlap of PBC and PSC.

It appears inappropriate to use the term overlap syndrome for coexistence of AIH and other chronic liver diseases like chronic hepatitis C. Autoantibodies are detected in up to 65% of patients with chronic hepatitis C and LKM1 antibodies, the hallmark of AIH type 2 was also observed in 7% of the patients with chronic hepatitis C[8]. Conversely, in patients with AIH and hypergammaglobulinemia, anti-HCV tests in the past turned out to be false positive in many cases[9]. Thus, the term overlap syndrome should not be used for patients with AIH and concomitant chronic hepatitis C.

This article is an extension of a recent review[10] and discusses current views and controversies on overlap syndromes. A case report is included to exemplify the typical features of an AIH-PBC overlap syndrome.

DIAGNOSIS OF AUTOIMMUNE LIVER DISEASES

The diagnostic criteria of AIH, PBC and PSC are discussed in detail in this issue of the World Journal of Gastroenterology and are therefore just summarized briefly, since they are the basis for the diagnosis of the respective overlap syndrome.

AIH

The diagnosis of AIH depends on several descriptive criteria which were summarized and updated by the International AIH Group (IAIHG) in 1999[11]. A definite diagnosis requires exclusion of other major causes of liver damage, including alcoholic, viral, drug- and toxin-induced, and hereditary liver disease. The scoring system includes characteristic laboratory features (hepatitic serum liver tests, the presence of elevated serum IgG or γ-globulins and of serum autoantibodies), histocompatibility leucocyte antigen (HLA) associations, a portal mononuclear cell infiltration and interface hepatitis in the liver tissue and a positive treatment response to corticosteroids[11].

PBC

The diagnosis of PBC is based on a cholestatic serum enzyme pattern, serum antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) and/or PBC-specific AMA-M2, and a compatible histology. Although elevated serum IgM is characteristic for patients with PBC, it is not regarded mandatory to establish the diagnosis[12,13]. PBC is frequently associated with other autoimmune disorders, like Sjögren’s syndrome, Hashimoto thyroiditis, and celiac disease.

PSC

PSC is a rare chronic cholestatic disease of the liver and bile ducts that is generally progressive and leads to end-stage liver disease. In contrast to PBC, twice as many men as women are affected. PSC is diagnosed most frequently in patients aged between 25 and 40 years[14]. Criteria for the diagnosis of PSC include cholestatic serum enzyme pattern, typical cholangiographic findings of bile duct stenoses and dilatations and histologic findings compatible with PSC showing mild to moderate portal infiltration[14,15]. Concomitant inflammatory bowel disease is found in 70%-90% of the patients and atypical perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmatic antibodies (pANCA) are detected in more than 70% of the patients[16].

AIH-PBC OVERLAP SYNDROME

PBC and AIH are the most frequent autoimmune hepatopathies with a prevalence of 25-40/100 000[17,18] and 17/100 000[19], respectively, in recent epidemiologic studies in Europe and the United States and female gender predominates in both AIH (80%) and PBC (90%-95%). Serum liver tests typically show a hepatitic pattern in AIH and a cholestatic pattern with marked elevation of aP and γ-GT, but mild elevation of serum transaminases in PBC. While serum IgG is the predominant immunoglobulin elevated in AIH, serum IgM is elevated in most patients with PBC.

Patients presenting with clinical, biochemical, serological and histological features of both diseases have been reported since the 1970s[20,21]. Later, the term “overlap syndrome” was used to describe these conditions, although there was no common definition or uniformly accepted diagnostic criteria for this[22,23]. Two extended analyses provided evidence for AIH-PBC overlap in 8% of 199 patients with AIH (n = 162) or PBC (n = 37)[1] and in 9% of 130 patients with PBC[5]. In the latter study, an AIH-PBC overlap syndrome was accepted when 2 or 3 criteria for PBC and AIH were fulfilled[5] (Table 1). Although these diagnostic criteria for an AIH-PBC overlap syndrome are not validated and their sensitivity has not been established, they provide a diagnostic template that can be consistently applied[4].

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome proposed by Chazouillères et al in 1998[5]

| AIH (2 out of 3 criteria) |

| (1) Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels > 5 × ULN |

| (2) Serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels > 2 × ULN or a positive test for smooth muscle antibodies (ASMA) |

| (3) Liver biopsy showing moderate or severe periportal orperiseptal lymphocytic piecemeal necrosis |

| PBC (2 out of 3 criteria) |

| (1) Alkaline phosphatase (AP) levels > 2 × or γ-glutamyltranspeptidase (GGT) levels > 5 × ULN |

| (2) Positive test for antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) |

| (3) Liver biopsy specimen showing florid bile duct lesions |

ULN: Upper limit of normal value.

In a comparative study, patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome presented with typical features of PBC (AMA-M2 positive, bile duct damage compatible with PBC), but a more hepatitic picture than a cohort of PBC patients[24]. Patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome showed a predominant HLA type B8, DR3, or DR4 similar to AIH and a good response to corticosteroid treatment, and this was, therefore, named “PBC, hepatitic form”[24]. Autoantibodies are generally believed to present a hallmark for the diagnosis of AIH, but up to 20% of patients with AIH present without antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMA), or antibodies against liver-kidney-microsomes (LKM) 1[11]. ANA represent the least specific serum autoantibodies for the diagnosis of chronic liver diseases and are also found in 30% of elderly healthy controls, 10% of pregnant women, and 30% of patients with malignancies[25]. Serum ANA in patients with PBC are not a marker of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome, but often found in PBC patients without further signs of AIH[26]. In contrast, ANA with a specific immunofluorescence pattern of multiple nuclear dots directed against Sp100 (5-10 dots) or Coilin p80 (2-6 dots) are rather specific although less sensitive for PBC[25]. In 3.9% of 233 patients with PBC, the presence of soluble liver antigen (SLA) autoantibodies was found to be a marker of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome with a good response to immunosuppressive therapy[27].

In addition to AIH-PBC overlap syndrome, some patients presented with typical features of PBC or AIH[5,28]. A well-defined series of 12 patients with PBC followed by AIH was described in 282 PBC patients[29]. The time interval between the diagnosis of PBC and the diagnosis of AIH varied from 6 mo to 13 years. Of importance, patients with multiple flares of hepatitis at the time of diagnosis of AIH had already developed cirrhosis on liver biopsy[29]. Remission was achieved in 80% of the patients who received additional immunosuppressive therapy. This case series emphasizes the possible role of AIH in the deterioration of liver function in PBC patients unless diagnosis is made early and steroid therapy is administered. This study suggested that these patients may have two coincident autoimmune diseases rather than a variant of PBC or AIH[29]. A recent retrospective analysis indicated that patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome might have worse clinical outcomes compared to patients with PBC alone[30]. However, this conclusion is somewhat controversial, since the treatment was not standardized and no difference was found when the diagnostic criteria proposed by Chazouilleres et al[5] were applied in this cohort of patients.

Therapy

Randomized controlled trials are the best method to address therapeutic issues. However, the low prevalence of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome has made controlled therapeutic trials in these patients impossible so far. Thus, therapeutic recommendations still rely on the experience in the treatment of either AIH or PBC, and on retrospective, non-randomized studies with inherent limitations. It remains controversial if patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome require immunosuppressive treatment in addition to ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA). In a strictly defined cohort of 16 patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome, the response to UDCA therapy (13-15 mg/kg daily) and the survival of the patients were similar to patients with classical PBC[31]. However, other groups reported that a combined therapy of UDCA and corticosteroids is required in most patients to obtain a complete biochemical response[5,24]. This question was addressed again recently in a retrospective study of 17 patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome[32]. In this study, patients received UDCA alone or UDCA in combination with immunosuppressors and were followed up for 7.5 years. In the patients treated with UDCA alone, biochemical response was observed in only 3 patients whereas 8 patients were non-responders and 50% of them showed increased fibrosis. All but one of the non-resonders subsequently received combined therapy, and 85% of the patients achieved biochemical remission[32]. In the second group of patients who received combined therapy throughout the study, fibrosis did not progress and 67% achieved biochemical remission. Thus, it appears appropriate to start treatment with UDCA (13-15 mg/kg daily). However, if this therapy does not induce an adequate biochemical response in an appropriate time span (e.g. 3 mo) or in patients with predominantly hepatitic serum liver tests, a glucocorticosteroid should be added. Prednisone has been used at an initial dose of 0.5 mg/kg daily and should be progressively tapered once ALT levels show a response[32]. The role of other immuno-suppressants, e.g. azathioprine (1-1.5 mg/kg daily) in the long-term management of patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome is unclear, but its successful use in AIH makes azathioprine an attractive alternative to corticosteroids for long-term immunosuppressive therapy[3,32]. Budesonide, a synthetic corticosteroid with a high first pass metabolism that reduces its systemic side effects, is a promising treatment option for patients with AIH and has also been used in patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome with success[33,34]. For corticosteroid-resistant patients with AIH-PBC overlap syndrome, intermediate treatment with other immunosuppressants such as cyclosporine A has been considered[23]. Liver transplantation is regarded as the treatment of choice for end-stage disease.

A case report of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome

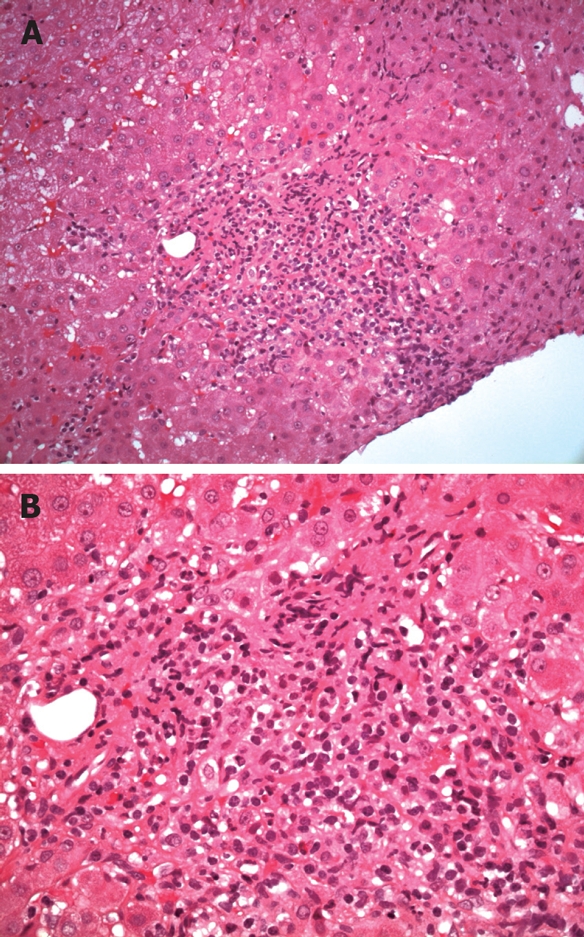

A 57-year-old woman presented to our outpatient clinic in May 2007 for evaluation of abnormal serum liver tests. She reported fatigue and slight pruritus, but was otherwise in good general health. In January 2007, elevated serum liver tests were detected for the first time when she went for a routine medical examination. At presentation, serum liver tests revealed elevated γ-GT (2 × N), elevated transaminases (AST 2.5 × N, ALT 5.5 × N), and normal bilirubin. Serum AMA (1:3840) and AMA-M2, ASMA and SLA were positive, whereas ANA, LKM1 and ANCA were all negative. Her immunoglobulins showed elevated IgG (23.2 g/L) and IgM (3.3 g/L). Metabolic and viral liver diseases were ruled out. A liver biopsy disclosed an interface hepatitis and mild portal fibrosis without evidence of cirrhosis (Figure 1). AIH-PBC overlap syndrome was diagnosed and a combined therapy of UDCA (13-15 mg/kg daily ) and budesonide (6 mg/d) was initiated. Two weeks later, her transaminases decreased by 50% and azathioprine (100 mg/d) was administered. After 3 mo of combined therapy, all serum liver tests were normal and budesonide was tapered to 3 mg/d. At the last follow-up visit in August 2007, the patient reported an improved general condition, and fatigue and pruritus disappeared.

Figure 1.

Overlap syndrome autoimmune hepatitis-primary biliary cirrhosis. A 57-year-old woman presented with elevated γ-GT (2 × ULN) and transaminases (AST 2.5 × ULN, ALT 5.5 × ULN), and normal bilirubin. Serum AMA (1:3840), AMA-M2,ASMA and SLA were positive. Her immunoglobulins showed elevated IgG (23.2 g/L) and IgM (3.3 g/L). A liver biopsy disclosed an interface hepatitis and mild portal fibrosis without evidence of cirrhosis. A: HE, × 20; B: HE, × 40 (Courtesy of Prof. Dr. Müller-Höcker, Munich).

AUTOIMMUNE CHOLANGITIS (AIC) AIC-AIH OVERLAP SYNDROME

AIC shares many features with PBC and is therefore also called AMA-negative PBC. Like PBC, it is characterized by a female preponderance, a cholestatic serum enzyme pattern and florid bile duct lesions on histology and it slowly progresses to fibrosis and cirrhosis of the liver if left untreated[35]. Patients with AIC are AMA negative and often present with serum ANA and/or ASMA. Several studies support the view that AIC and PBC are variants of one single disease only differing in serum autoantibody pattern[36–38]. Twenty-two of 30 patients with AIC (AMA-negative PBC), but none of the 316 controls, were positive in a new AMA-M2 recombinant assay which detected autoantibodies directed against human E2 members of the 2-oxo acid dehydrogenase complex family[36]. In addition, immunohistochemical studies showed that PDC-E2 immunoreactivity was expressed on apical membranes of biliary epithelial cells not only in patients with PBC, but also in 7 of 9 patients with AIC[37]. Treatment response to UDCA (13-15 mg/kg daily) and outcome of liver transplantation in end-stage disease were also similar in patients with AIC and those with PBC[39,40]. Thus, these data indicate that a majority of AIC patients (when defined as AMA-negative PBC) suffer from “true” PBC.

Concomitant features of AIH and AIC have been reported in single cases. An AMA-negative woman presented with features of an AIH-AIC overlap syndrome based on the presence of hepatitic and cholestatic biochemical changes and interface hepatitis as well as bile duct lesions on histology. In analogy to the therapy of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome, this patient responded to a combined treatment with UDCA and immunosuppressors[41].

AIH-PSC OVERLAP SYNDROME

While AIH-PBC overlap syndrome is predominantly found among adults, AIH-PSC overlap syndromes have mainly been described in children, adolescents and young adults[42–44]. Use of the modified AIH score led to the diagnosis of an overlap syndrome in 8% of 113 PSC patients and 1.4% of 211 PSC patients, respectively, when evaluated retrospectively[45,46]. However, diagnostic criteria are not defined for AIH-PSC overlap syndrome which makes comparability of these studies difficult. In a recently published prospective study, 41 consecutive patients who were diagnosed with PSC were evaluated for an AIH-PSC overlap syndrome[47]. The diagnosis of AIH-PSC overlap syndrome was established when the following criteria were met: (1) revised AIH score > 15; (2) ANA or ASMA antibodies present in a titre of at least 1:40; and (3) liver histology with piecemeal necrosis, lymphocyte rosetting, moderate or severe periportal or periseptal inflammation[47]. By applying these criteria, 17% of the PSC patients were diagnosed with AIH-PSC overlap syndrome. Patients with AIH-PSC overlap syndrome were treated with UDCA (15-20 mg/kg daily), prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg daily, tapered to 10-15 mg/d) and 50-75 mg azathioprine with good biochemical response[47]. Of interest, the survival probability of the patients with AIH-PSC overlap syndrome was better than those with classical PSC as assessed by the Mayo score, a prognostic index.

The largest case series of AIH-PSC overlap syn-dromes in children and adolescents was published by colleagues from the Kings’ College in London[44]. In this prospective study, a group of 55 children was followed up for 16 years who showed clinical, biochemical, and histological signs of AIH. In 27 of the 55 children, cholangiographic findings were typical of sclerosing cholangitis, whereas other signs and symptoms were characteristic of AIH. Therefore, the term “autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis” (ASC) was proposed for this AIH-PSC overlap syndrome. Patients with ASC more commonly suffered from inflammatory bowel disease and more often were positive for ANCA in serum than those with AIH. Serum transaminases tended to be higher in AIH, but serum alkaline phosphatase although mostly elevated in PSC was normal at several occasions in both diseases. Thus, AIH and ASC may belong to the same disease process and may overlap with PSC.

Increasing awareness for the AIH-PSC overlap syndrome has led to the observation that AIH and PSC may be sequential in their occurrence, and this has first been described in children[44]. More recently, a similar observation has been reported in a small case series of 6 adults (mean age 31 years; 4 male; 3 with ulcerative colitis) who developed biochemical and cholangiographic features of PSC after an average of 4.6 years of a diagnosis of AIH and became resistant to immunosuppressive therapy[6]. Thus, in patients with AIH who become cholestatic and/or resistant to immunosuppression, PSC should be considered and ruled out.

Therapy

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is widely administered in PSC due to its beneficial effects on serum liver tests, histological features, prognostic surrogate markers, and development of colonic dysplasia associated with accompanying ulcerative colitis, although long-term efficacy of UDCA still remains unproven[48–52]. UDCA at higher doses (> 20 mg/kg daily) may be superior to standard doses for patients with PSC[53] and has also been used in the treatment of AIH-PSC overlap syndrome[47,52]. UDCA has been used in combination with immunosuppressive drugs in AIH-PSC overlap syndrome, and the long-term course was considered favorable[44,47]. Thus, UDCA in combination with an immunosuppressive regimen may be an adequate medical treatment for most patients with AIH-PSC overlap syndrome although data from controlled trials are lacking. Liver transplantation should be considered in late-stage diseases.

Footnotes

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Yin DH

References

- 1.Czaja AJ. The variant forms of autoimmune hepatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:588–598. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-7-199610010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poupon R. Autoimmune overlapping syndromes. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:865–878. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(03)00092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beuers U. Hepatic overlap syndromes. J Hepatol. 2005;42 Suppl:S93–S99. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Ari Z, Czaja AJ. Autoimmune hepatitis and its variant syndromes. Gut. 2001;49:589–594. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chazouilleres O, Wendum D, Serfaty L, Montembault S, Rosmorduc O, Poupon R. Primary biliary cirrhosis-autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome: clinical features and response to therapy. Hepatology. 1998;28:296–301. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdo AA, Bain VG, Kichian K, Lee SS. Evolution of autoimmune hepatitis to primary sclerosing cholangitis: A sequential syndrome. Hepatology. 2002;36:1393–1399. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.37200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burak KW, Urbanski SJ, Swain MG. A case of coexisting primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis: a new overlap of autoimmune liver diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2043–2047. doi: 10.1023/a:1010620122567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pawlotsky JM, Ben Yahia M, Andre C, Voisin MC, Intrator L, Roudot-Thoraval F, Deforges L, Duvoux C, Zafrani ES, Duval J. Immunological disorders in C virus chronic active hepatitis: a prospective case-control study. Hepatology. 1994;19:841–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lunel F, Cacoub P. Treatment of autoimmune and extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 1999;31 Suppl 1:210–216. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beuers U, Rust C. Overlap syndromes. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:311–320. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, Chapman PW, Cooksley WG, Czaja AJ, Desmet VJ, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929–938. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80297-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prince MI, Chetwynd A, Craig WL, Metcalf JV, James OF. Asymptomatic primary biliary cirrhosis: clinical features, prognosis, and symptom progression in a large population based cohort. Gut. 2004;53:865–870. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.023937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vierling JM. Primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune cholangiopathy. Clin Liver Dis. 2004;8:177–194. doi: 10.1016/S1089-3261(03)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poupon R, Chazouilleres O, Poupon RE. Chronic cholestatic diseases. J Hepatol. 2000;32:129–140. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80421-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaRusso NF, Shneider BL, Black D, Gores GJ, James SP, Doo E, Hoofnagle JH. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2006;44:746–764. doi: 10.1002/hep.21337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee YM, Kaplan MM. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:924–933. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504063321406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim WR, Lindor KD, Locke GR 3rd, Therneau TM, Homburger HA, Batts KP, Yawn BP, Petz JL, Melton LJ 3rd, Dickson ER. Epidemiology and natural history of primary biliary cirrhosis in a US community. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1631–1636. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prince MI, James OF. The epidemiology of primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:795–819. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(03)00102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boberg KM. Prevalence and epidemiology of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6:635–647. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(02)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kloppel G, Seifert G, Lindner H, Dammermann R, Sack HJ, Berg PA. Histopathological features in mixed types of chronic aggressive hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis. Correlations of liver histology with mitochondrial antibodies of different specificity. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1977;373:143–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00432159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okuno T, Seto Y, Okanoue T, Takino T. Chronic active hepatitis with histological features of primary biliary cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:775–779. doi: 10.1007/BF01296147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis PA, Leung P, Manns M, Kaplan M, Munoz SJ, Gorin FA, Dickson ER, Krawitt E, Coppel R, Gershwin ME. M4 and M9 antibodies in the overlap syndrome of primary biliary cirrhosis and chronic active hepatitis: epitopes or epiphenomena? Hepatology. 1992;16:1128–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duclos-Vallee JC, Hadengue A, Ganne-Carrie N, Robin E, Degott C, Erlinger S. Primary biliary cirrhosis-autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome. Corticoresistance and effective treatment by cyclosporine A. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1069–1073. doi: 10.1007/BF02064201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lohse AW, zum Buschenfelde KH, Franz B, Kanzler S, Gerken G, Dienes HP. Characterization of the overlap syndrome of primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and autoimmune hepatitis: evidence for it being a hepatitic form of PBC in genetically susceptible individuals. Hepatology. 1999;29:1078–1084. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terjung B, Spengler U. Role of auto-antibodies for the diagnosis of chronic cholestatic liver diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2005;28:115–133. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:28:2:115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Invernizzi P, Selmi C, Ranftler C, Podda M, Wesierska-Gadek J. Antinuclear antibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:298–310. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanzler S, Bozkurt S, Herkel J, Galle PR, Dienes HP, Lohse AW. [Presence of SLA/LP autoantibodies in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis as a marker for secondary autoimmune hepatitis (overlap syndrome)] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2001;126:450–456. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colombato LA, Alvarez F, Cote J, Huet PM. Autoimmune cholangiopathy: the result of consecutive primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune hepatitis? Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1839–1843. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90829-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poupon R, Chazouilleres O, Corpechot C, Chretien Y. Development of autoimmune hepatitis in patients with typical primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2006;44:85–90. doi: 10.1002/hep.21229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silveira MG, Talwalkar JA, Angulo P, Lindor KD. Overlap of autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: long-term outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1244–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joshi S, Cauch-Dudek K, Wanless IR, Lindor KD, Jorgensen R, Batts K, Heathcote EJ. Primary biliary cirrhosis with additional features of autoimmune hepatitis: response to therapy with ursodeoxycholic acid. Hepatology. 2002;35:409–413. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chazouilleres O, Wendum D, Serfaty L, Rosmorduc O, Poupon R. Long term outcome and response to therapy of primary biliary cirrhosis-autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome. J Hepatol. 2006;44:400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiegand J, Schuler A, Kanzler S, Lohse A, Beuers U, Kreisel W, Spengler U, Koletzko S, Jansen PL, Hochhaus G, et al. Budesonide in previously untreated autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int. 2005;25:927–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Csepregi A, Rocken C, Treiber G, Malfertheiner P. Budesonide induces complete remission in autoimmune hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1362–1366. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i9.1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heathcote J. Autoimmune cholangitis. Gut. 1997;40:440–442. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.4.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyakawa H, Tanaka A, Kikuchi K, Matsushita M, Kitazawa E, Kawaguchi N, Fujikawa H, Gershwin ME. Detection of antimitochon drial autoantibodies in immunofluorescent AMA-negative patients with primary biliary cirrhosis using recombinant autoantigens. Hepatology. 2001;34:243–248. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuneyama K, Van De Water J, Van Thiel D, Coppel R, Ruebner B, Nakanuma Y, Dickson ER, Gershwin ME. Abnormal expression of PDC-E2 on the apical surface of biliary epithelial cells in patients with antimitochondrial antibody-negative primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1995;22:1440–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ikuno N, Scealy M, Davies JM, Whittingham SF, Omagari K, Mackay IR, Rowley MJ. A comparative study of antibody expressions in primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune cholangitis using phage display. Hepatology. 2001;34:478–486. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim WR, Poterucha JJ, Jorgensen RA, Batts KP, Homburger HA, Dickson ER, Krom RA, Wiesner RH, Lindor KD. Does antimitochondrial antibody status affect response to treatment in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis? Outcomes of ursodeoxycholic acid therapy and liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1997;26:22–26. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lacerda MA, Ludwig J, Dickson ER, Jorgensen RA, Lindor KD. Antimitochondrial antibody-negative primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:247–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li CP, Tong MJ, Hwang SJ, Luo JC, Co RL, Tsay SH, Chang FY, Lee SD. Autoimmune cholangitis with features of autoimmune hepatitis: successful treatment with immunosuppressive agents and ursodeoxycholic acid. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:95–98. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McNair AN, Moloney M, Portmann BC, Williams R, McFarlane IG. Autoimmune hepatitis overlapping with primary sclerosing cholangitis in five cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:777–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.224_a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Buuren HR, van Hoogstraten HJE, Terkivatan T, Schalm SW, Vleggaar FP. High prevalence of autoimmune hepatitis among patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2000;33:543–548. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0641.2000.033004543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gregorio GV, Portmann B, Karani J, Harrison P, Donaldson PT, Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. Autoimmune hepatitis/sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome in childhood: a 16-year prospective study. Hepatology. 2001;33:544–553. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaya M, Angulo P, Lindor KD. Overlap of autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis: an evaluation of a modified scoring system. J Hepatol. 2000;33:537–542. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0641.2000.033004537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Buuren HR, van Hoogstraten HJE, Terkivatan T, Schalm SW, Vleggaar FP. High prevalence of autoimmune hepatitis among patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2000;33:543–548. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0641.2000.033004543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Floreani A, Rizzotto ER, Ferrara F, Carderi I, Caroli D, Blasone L, Baldo V. Clinical course and outcome of autoimmune hepatitis/primary sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1516–1522. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rust C, Beuers U. Medical treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2005;28:135–145. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:28:2:135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beuers U, Spengler U, Kruis W, Aydemir U, Wiebecke B, Heldwein W, Weinzierl M, Pape GR, Sauerbruch T, Paumgartner G. Ursodeoxycholic acid for treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis: a placebo-controlled trial. Hepatology. 1992;16:707–714. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stiehl A, Walker S, Stiehl L, Rudolph G, Hofmann WJ, Theilmann L. Effect of ursodeoxycholic acid on liver and bile duct disease in primary sclerosing cholangitis. A 3-year pilot study with a placebo-controlled study period. J Hepatol. 1994;20:57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80467-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lindor KD. Ursodiol for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Mayo Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis-Ursodeoxycholic Acid Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:691–695. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703063361003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitchell SA, Bansi DS, Hunt N, Von Bergmann K, Fleming KA, Chapman RW. A preliminary trial of high-dose ursodeoxycholic acid in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:900–907. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.27965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cullen SN, Rust C, Flemming K, Edwards C, Beuers U, Chapman RW. High dose ursodeoxycholic acid for the treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis is safe and effective. J Hepatol. 2008;48:792–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]