Abstract

Amphetamine (AMPH) is a potent dopamine (DA) transporter (DAT) inhibitor that markedly increases extracellular DA levels. In addition to its actions as a DAT antagonist, acute AMPH exposure induces DAT losses from the plasma membrane, implicating transporter-specific membrane trafficking in amphetamine’s actions. Despite reports that AMPH modulates DAT surface expression, the trafficking mechanisms leading to this effect are currently not defined. We recently reported that DAT residues 587–596 play an integral role in constitutive and protein kinase C (PKC)-accelerated DAT internalization. In the current study, we tested whether the structural determinants required for PKC-stimulated DAT internalization are necessary for AMPH-induced DAT sequestration. Acute amphetamine exposure increased DAT endocytic rates, but DAT carboxy terminal residues 587–590, which are required for PKC-stimulated internalization, were not required for AMPH-accelerated DAT endocytosis. AMPH decreased DAT endocytic recycling, but did not modulate transferrin receptor recycling, suggesting that AMPH does not globally diminish endocytic recycling. Finally, treatment with a PKC inhibitor demonstrated that AMPH-induced DAT losses from the plasma membrane were not dependent upon PKC activity. These results suggest that the mechanisms responsible for AMPH-mediated DAT internalization are independent from those governing PKC-sensitive DAT endocytosis.

Keywords: Uptake, Dopamine, Amphetamine, Trafficking, Endocytosis

1. Introduction

DA is a major central nervous system neurotransmitter that is critical for movement, cognition and rewarding behaviors (Brooks, 2001; Carlsson et al., 2007; Cohen et al., 2002; Sora et al., 2001). Following its exocytic release, synaptic DA signaling is rapidly terminated by presynaptic reuptake processes, mediated by the neuronal dopamine transporter (DAT). DAT is member of the sodium- and chloride-dependent SLC6 carrier gene family, which includes neuronal transporters responsible for GABA, 5-HT, NE and glycine clearance (Chen et al., 2004; Gether et al., 2006). In addition to its central role in basal neurotransmission, DAT is the primary target for many psychoactive drugs that potently and competitively inhibit reuptake, including: cocaine, methamphetamine, (+)-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA; “ecstasy”), fluoxetine (Prozac), bupropion (Zyban, Wellbutrin) and methylphenidate (Ritalin) (Barker and Blakely, 1995; Kim et al., 2000; Nelson, 1998). These inhibitors raise extracellular DA levels (Chen and Reith, 1994; Wayment et al., 2001; Wilson et al., 1996) and concomitantly enhance downstream DA signaling (LaHoste et al., 2000; Scarponi et al., 1999). In addition to being an antagonist, AMPH is also a DAT substrate that is transported into the cytosol (Rothman and Baumann, 2003; Sulzer et al., 2005). There, it drives DA efflux back through the transporter in a PKC- (Johnson et al., 2005b) and Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II (CamKII)- (Fog et al., 2006) dependent manner.

While clearly a major pharmacological target, DAT activity can also be acutely regulated by a number of cellular signaling pathways, many of which modulate DAT plasma membrane expression via membrane trafficking-dependent processes. For example, both PKC and MAP kinase acutely regulate DAT function by manipulating DAT surface levels (Melikian, 2004; Robinson, 2002; Zahniser and Doolen, 2001). DAT trafficking is not limited to instances of cellular regulation. Rather, DAT constitutively internalizes (Holton et al., 2005; Li et al., 2004; Loder and Melikian, 2003; Sorkina et al., 2005) and recycles back to the plasma membrane (Loder and Melikian, 2003), with a surface half-life of ~13 min. PKC-mediated decreases in DAT surface levels are achieved by increasing DAT endocytic rates, and in parallel decreasing DAT endocytic delivery to the cell surface (Loder and Melikian, 2003).

Recent studies indicate that in addition to its effects on DAT function, acute AMPH exposure also decreases DAT surface expression in vivo (Sandoval et al., 2000, 2001), in heterologous expression systems (Chi and Reith, 2003; Gulley et al., 2002; Kahlig et al., 2006; Saunders et al., 2000) and in striatal synaptosomes (Johnson et al., 2005a). AMPH-mediated DAT redistribution requires the translocation of AMPH to the cytosol (Kahlig et al., 2006), and also requires CamKII activation (Wei et al., 2007). AMPH transport into the cytosol inhibits Akt (Garcia et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2007), a protein kinase involved in insulin-stimulated delivery of the glucose transporter, GLUT4, to the plasma membrane (Ishiki and Klip, 2005; Whiteman et al., 2002). Moreover, Akt activity is required to maintain steady state DAT surface levels (Garcia et al., 2005).

We recently identified a ten amino acid region in the DAT carboxy terminal spanning residues 587–591 that is required for PKC-mediated DAT downregulation (Holton et al., 2005). Using mutagenesis to further examine this region, we found that residues 587–590 (FREK) were necessary for PKC-mediated effects on DAT internalization rates (Boudanova and Melikian, unpublished observations). In the current study, we asked whether the same determinants that mediate PKC-induced DAT sequestration also govern AMPH-stimulated DAT surface losses. Our results demonstrate that AMPH stimulates DAT endocytic rates and markedly suppresses DAT endocytic recycling early after AMPH exposure. However, neither PKC activity nor PKC-sensitive DAT endocytic determinants are necessary for AMPH-stimulated DAT surface losses. These results suggest that AMPH-mediated effects on DAT trafficking are independent of PKC activity and mechanistically distinct from those governing PKC-mediated DAT downregulation.

2. Methods

2.1. Materials

Monoclonal rat anti-DAT antibodies were from Chemicon (Temecula, CA), mouse anti-transferrin receptor antibodies were from Invitrogen (clone H68.4, Carlsbad, CA) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). [3H]DA (dihydroxyphenylethylamine 3,4-[ring-2,5,6,-3H] was from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA) and sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin was from Pierce (Rockford, IL). All other chemicals and reagents were from Sigmae–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and were of the highest grade possible.

2.2. cDNA constructs

hDAT cDNA was cloned into pcDNA 3.1(+) as previously described (Holton et al., 2005). Mutagenesis was performed with the Quickchange site-directed mutagenesis system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). All mutants were subcloned back into the parental hDAT plasmid at the ClaI/XbaI site. Sequences were verified by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Nucleic Acid Facility.

2.3. Cell culture and stable cell lines

DAT-PC12 cell lines expressing wild type or the 587–590(4A) DAT mutant were generated as previously described (Melikian and Buckley, 1999). Stable transformants were selected in the presence of 0.5 mg/ml geneticin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and were pooled. Pooled cell lines were cultured in 10% CO2 in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (high glucose) containing 5% bovine calf serum supplemented (Hyclone), 5% horse serum (Invitrogen), 2 mM glutamine, 102 units/ml penicillin–streptomycin and were maintained under selective pressure with 0.2 mg/ml geneticin.

2.4. [3H]DA uptake assay

Cells were washed in Krebs–Ringers–HEPES buffer (KRH: 120 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) and incubated for 30 min, 37 °C in KRH buffer containing 0.18% glucose and either vehicle or the indicated drugs. All uptake conditions contained 100 nM desipramine to eliminate DA uptake by the endogenous NE transporter. Uptake was initiated by addition of 1 µM [3H]DA, proceeded for 10 min, and was terminated by rapidly washing three times with ice-cold KRH buffer. Non-specific uptake was defined in the presence of 10 µM GBR12935. Cells were solubilized in liquid scintillant, and accumulated radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting in a Wallac Microbeta scintillation plate reader (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA).

2.5. Cell-surface biotinylation

Cells were washed with prewarmed (37 °C) PBS2+ (137 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM phosphate buffer, 2.7 mM potassium chloride, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) supplemented with 0.2% immunoglobulin- and protease-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.18% glucose (PBS2+/BSA/glucose) containing the indicated drugs. Cells were subsequently incubated in the same solutions, 30 min, 37 °C. Incubations were rapidly stopped by placing cells on ice and washing them repeatedly with ice-cold PBS2+. Cells were surface biotinylated with 1.0 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (Pierce, Rockford, IL), as described previously (Holton et al., 2005; Loder and Melikian, 2003), and were subsequently lysed in RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1.0% Triton X-100, and 1.0% sodium deoxycholate) with protease inhibitors (1.0 mM PMSF, 1.0 µg/ml aprotinin, 1.0 µg/ml pepstatin, and 1.0 µg/ml leupeptin). Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein assay (Pierce). Biotinylated and non-biotinylated proteins from equivalent amounts of cell lysate were separated by batch streptavidin affinity chromatography, and supernatants were concentrated by spin filtration using columns with a 30 kDa molecular weight cutoff (Millipore). Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot and immunoreactive bands were detected with SuperSignal West Dura Extended substrate (Pierce). Non-saturating, immunoreactive bands were captured using a CCD camera gel documentation system and bands in the liner range of detection were quantified using Quantity One software (BioRad, Hercules, CA).

2.6. Internalization assays

Relative endocytic rates over an initial 10 min internalization period were measured using reversible surface biotinylation as previously described (Holton et al., 2005; Loder and Melikian, 2003). Briefly, cells were surface biotinylated with 2.5 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin. To initiate endocytosis, cells were repeatedly washed with prewarmed PBS2+/BSA/glucose and incubated in the same solution for 10 min at 37 °C. Endocytosis was rapidly stopped by placing cells on ice and washing them with ice-cold NT buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2% bovine serum albumin, 20 mM Tris, pH 8.6). Residual surface biotin was stripped by reducing surface disulfide bonds in freshly prepared 50 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP, Pierce) in NT buffer, 20 min, 4 °C × 2. Strip efficiencies were determined for each experiment on biotinylated cells kept in parallel at 4 °C and averaged >90%. Cells were subsequently lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors, and biotinylated proteins were isolated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot as described above. Internalization was measured as the %DAT biotinylated (internalized) compared to control samples kept in parallel at 4 °C.

2.7. Endocytic recycling/surface delivery assay

Cells were biotinylated at 4 °C as described above, to label the initial surface pool at t = 0 min. Zero minute timepoints remained at 4 °C, while cells for recycling timepoints were rapidly warmed to 37 °C. Proteins newly delivered to the plasma membrane (i.e. recycled) were identified by their ability to be biotinylated at 37 °C with the membrane impermeant reagent sulfo-NSH-SS-biotin. Cells were washed with prewarmed (37 °C) PBS2+/glucose containing the indicated drugs, and were biotinylated with 1.0 mg/ml sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin in PBS2+/glucose, 37 °C, for the indicated times. Biotinylation was rapidly quenched with 100 mM glycine, 2 × 15 min, 4 °C, and cells were lysed in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors. Biotinylated and non-biotinylated proteins from equal amounts of cell lysate were separated by streptavidin pull-down and samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot as described above. Recycling to the cell surface was measured as the % increase in biotinylation at 37 °C over 4 °C (t = 0 min) control samples. Data were fit to the first order exponential equation y = P + Ae(−x/τ), where y = % total biotinylation, P = Ymax, A = Ymax − Ymin, x is the time (min), and τ is a time constant. Recycling rates were calculated as 1/τ, and intracellular half-lives were calculated as τ × ln2.

3. Results

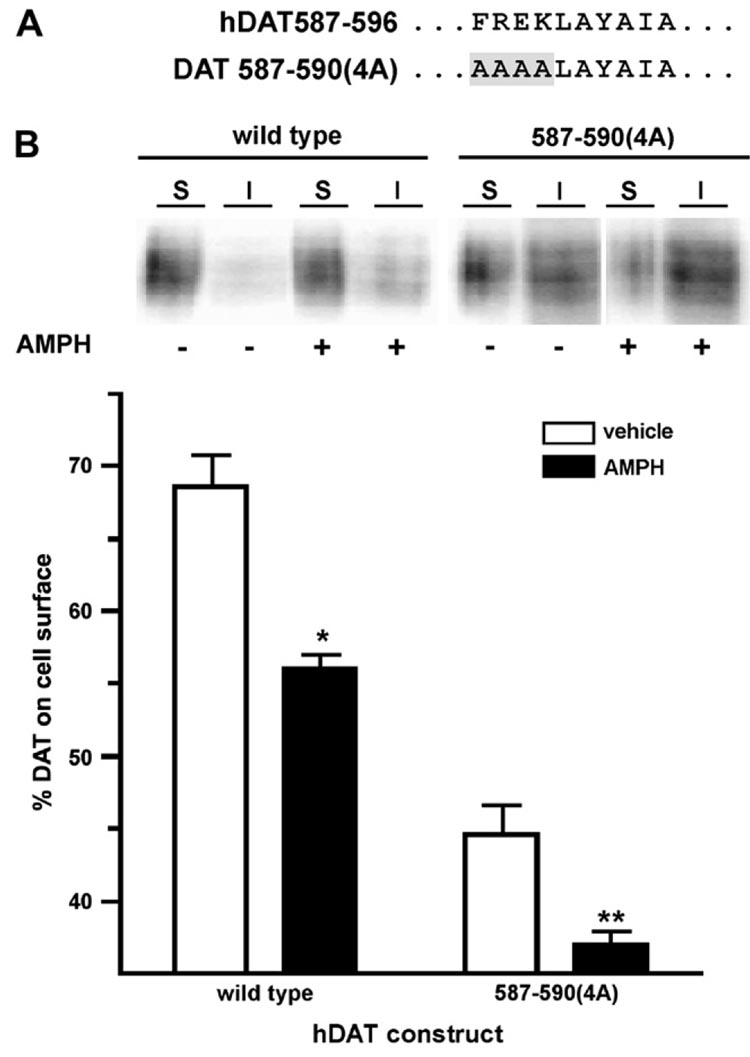

Although several studies have demonstrated that AMPH acutely reduces DAT surface expression (Garcia et al., 2005; Kahlig and Galli, 2003; Kahlig et al., 2006; Saunders et al., 2000; Wei et al., 2007), the trafficking mechanisms underlying this phenomenon have not been elucidated. We recently demonstrated that DAT residues 587–590 are critical for PKC-stimulated DAT endocytosis (Boudanova and Melikian, unpublished results) and decreased surface expression (Holton et al., 2005). In the current study, we asked: (1) whether PKC-sensitive determinants and (2) whether PKC activity are required for AMPH-induced DAT losses from the plasma membrane. We first tested whether AMPH exposure reduced DAT surface levels in PC12 cells transfected with either wild type or the DAT mutant 587–590(4A) (see Fig. 1A), which does not exhibit increased endocytosis or surface losses in response to PKC activation (Boudanova and Melikian, unpublished results). Cell surface biotinylation revealed that acute (30 min) AMPH treatment significantly decreased wild type DAT surface levels (Fig. 1B), but had no effect on total DAT levels (110.6 ± 4.5% of vehicle-treated cells, n = 9). AMPH exposure also significantly decreased surface levels of the PKC-insensitive DAT mutant 587–590(4A) (Fig. 1B), and the magnitude of the 587–590(4A) response to AMPH was not significantly different from that of wild type (wild type 18.3 ± 1.7% vs. 587–590(4A) 14.9 ± 3.7; Student’s t-test, p = 0.38, n = 7–9).

Fig. 1.

Amphetamine decreases in DAT surface levels do not require PKC-sensitive DAT structural determinants. (A) Schematic illustrating the 587–596 region of wild type and 587–590(4A) DAT. (B) Cell surface biotinylation. PC12 cells stably transfected with the indicated DAT constructs were treated ±5 µM AMPH, 30 min, 37 °C and surface DAT levels were measured by cell surface biotinylation as described in Section 2. Top: representative immunoblot showing surface (S) and intracellular (I) fractions from biotinylated cells following treatment with ±5 µM AMPH. Bottom: averaged data. Bars represent the percent total DAT on the cell surface following drug treatment ± SEM. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from vehicle control for each construct: *p < 0.0001, **p < 0.007; Student’s t-test (n = 7–9).

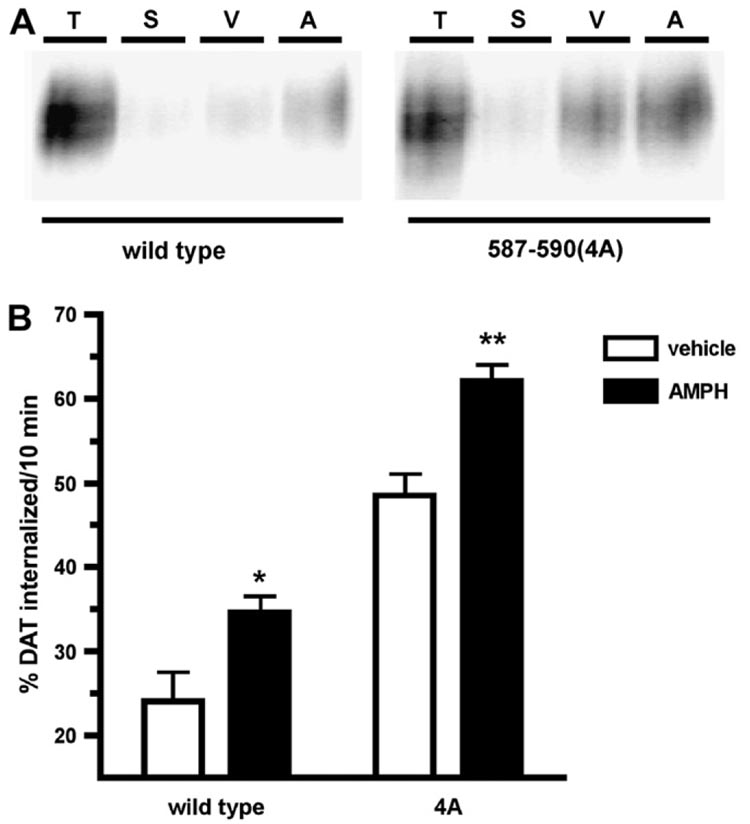

AMPH-induced DAT surface losses could result from increased endocytosis, decreased recycling, or both. It is currently not known which of these trafficking kinetic parameters is affected by AMPH exposure. We tested these possibilities by measuring the effects of AMPH on DAT endocytic and surface delivery rates in DAT-PC12 cells. Consistent with previous reports (Holton et al., 2005; Li et al., 2004; Loder and Melikian, 2003), DAT basally internalized from the cell surface at 24 ± 3.5%/10 min. Treatment with 5 µM AMPH significantly increased DAT endocytic rates to 34 ± 2%/10 min (Fig. 2B), which translates into a 58.7% increase in endocytic rates over basal levels. We next tested whether the molecular determinants required for PKC stimulation of DAT endocytosis were also required for AMPH-stimulated DAT internalization, by measuring the DAT 587–590(4A) endocytic rate under basal and AMPH-treated conditions. Consistent with results from our laboratory (Boudanova and Melikian, unpublished results), DAT 587–590(4A) internalized at a significantly higher rate than wild type under basal conditions (587–590(4A) 48.5 ± 2.6%/10 min; wild type 24.0 ± 3.5%/10 min; Fig. 2A). Despite its inability to increase its endocytic rate in response to PKC activation, AMPH significantly increased DAT 587–590(4A) endocytic rates (Fig. 2). Moreover, the magnitude of the AMPH effect on DAT endocytic rates was not significantly different between wild type and the 587–590(4A) mutant (wild type 58.6 ± 18.3% vs. 587–590(4A) 31.0 ± 8.9; Student’s t-test, p = 0.20, n = 8). These results, taken together with our results on DAT surface expression (Fig. 1), suggest that the mechanisms mediating AMPH-induced DAT sequestration are independent from those governing PKC-mediated DAT surface losses.

Fig. 2.

AMPH stimulates DAT endocytic rates but does not require DAT residues 587–590. Internalization assay. PC12 cells stably transfected with the indicated DAT cDNAs were biotinylated at 4 °C and were warmed for 10 min, 37 °C, ±5 µM AMPH. Residual surface biotin was stripped by reducing and internalized (biotinylated) proteins were identified by streptavidin affinity chromatography and immunoblot as described in Section 2. (A) Representative immunoblot showing total surface DAT at t = 0 min (T), strip controls (S) and amount of DAT internalized in the presence of either vehicle (V) or AMPH (A). (B) Averaged data. Bars represent percent total surface DAT ± SEM internalized in 10 min, ±5 µM AMPH. Asterisks indicate significant difference from vehicle-treated controls for each construct: *p < 0.03, **p < 0.002; Student’s t-test, n = 8.

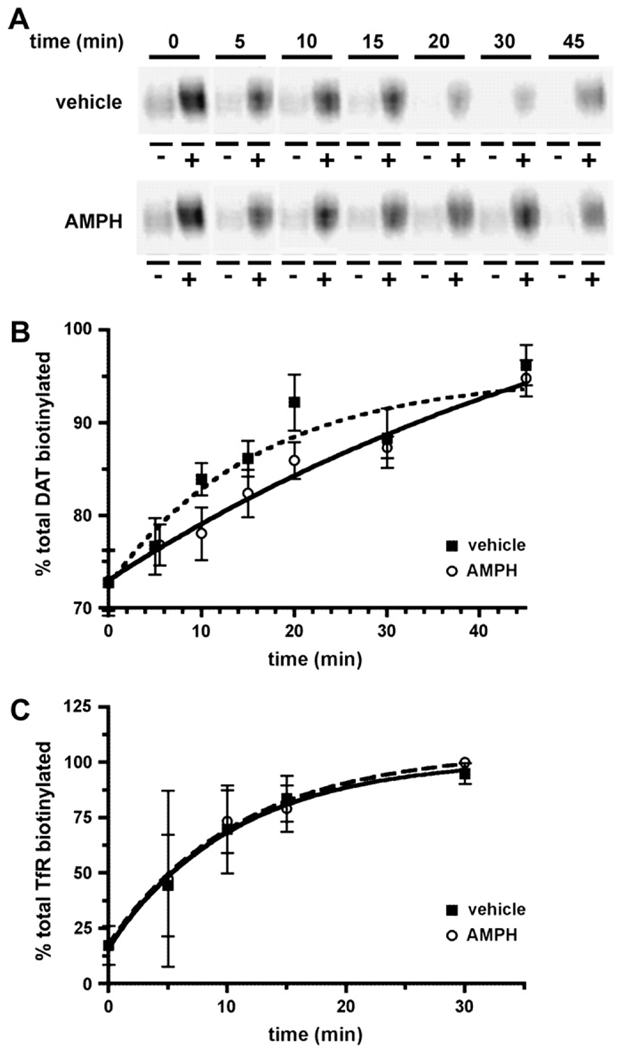

We next asked whether AMPH affected DAT delivery from the endocytic recycling compartment to the cell surface. As previously described (Loder and Melikian, 2003), we used a biotinylation approach to measure DAT surface delivery rates. In this assay, DAT is biotinylated under either trafficking restrictive (4 °C) or trafficking permissive (37 °C) conditions for increasing timepoints. As DAT is delivered to the cell surface, it gains access to the membrane impermeant biotinylation reagent and the percentage of biotinylated DAT increases, indicating surface delivery from internal pools. Under basal conditions, we observed an increase over time in the percentage of DAT biotinylated, indicating DAT surface delivery (Fig. 3A). DAT delivery to the plasma membrane followed first order kinetics (r2 = 0.94), with an average rate of 0.062/min, which translates into an intracellular half-life of 11.2 min. During AMPH treatment, DAT recycling kinetics also followed first order kinetics (r2 = 0.98; Fig. 3A), but were markedly slower from those observed in vehicle-treated cells. In the presence of AMPH, DAT recycling rates averaged 0.015/min, which corresponds to an intracellular half-life of 44.9 min (Fig. 3A). To test whether AMPH effects on DAT were specific, or reflected global changes in endocytic recycling, we assessed the effects of AMPH on transferrin receptor (TfR) recycling, a protein known to undergo rapid endocytic recycling. Under basal conditions TfR delivery to the plasma membrane followed first order kinetics (r2 = 0.99; Fig. 3B) with an average rate of 0.07 ± 0.03/min, which translates into an intracellular half-life of 10.2 ± 5.2 min. During AMPH exposure, TfR delivery to the cell surface continued to follow first order kinetics (r2 = 0.99; Fig. 3B) with an average recycling rate of 0.06 ± 0.03/min, which was not significantly different from that measured in the presence of vehicle ( p = 0.91, Student’s t-test, n = 3). These data suggest that AMPH specifically slows DAT delivery to the plasma membrane during the first 10 min of AMPH exposure, without globally affecting endocytic recycling.

Fig. 3.

AMPH decreases DAT delivery to the cell surface, but does not slow global endocytic recycling. Endocytic recycling assay: surface proteins were biotinylated at 4 °C and proteins newly delivered to the cell surface were identified by biotinylating at 37 °C, ±5 µM AMPH for the indicated times as described in Section 2. Data are expressed as the percent total protein biotinylated at the indicated times ± SEM. (A) Representative immunoblot showing non-biotinylated (−) and biotinylated (+) DAT fractions obtained at the indicated times after shifting cells to 37 °C, ±5 µM AMPH. (B) Averaged data. Points represent percent total DAT biotinylated ± SEM from vehicle- (dashed line) and AMPH-treated (solid line) cells at the indicated timepoints. Zero timepoints for vehicle- and AMPH-treated cells are identical. Data were fit to a first order exponential equation as described in Section 2. The r2 values: vehicle = 0.94, AMPH ¼ 0.98. (C) TfR recycling measured from the DAT immunoblots, stripped and re-probed with anti-TfR antibodies. Data from vehicle- (dashed line) and AMPH-treated (solid line) cells were fit to a first order exponential equation as described in Section 2. The r2 values: vehicle = 0.99, AMPH = 0.99.

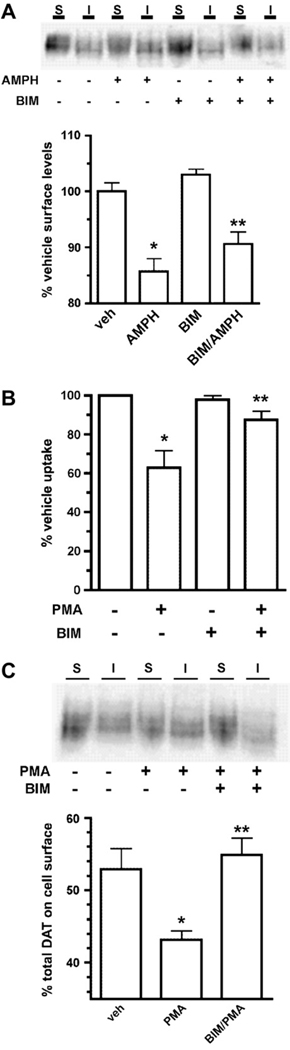

Several studies indicate that PKC activity is required for AMPH-mediated DA efflux through DAT (Cowell et al., 2000; Johnson et al., 2005b; Kantor and Gnegy, 1998). However, it is currently not known whether PKC activity is required for AMPH-induced DAT sequestration. Using a surface biotinylation approach, we directly tested whether PKC activity was required for AMPH-stimulated DAT surface losses. Consistent with our results in Fig. 1, 5 µM AMPH treatment for 30 min significantly decreased DAT surface levels (Fig. 4A). Treatment with the PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide I (BIM) alone had no effect on DAT surface levels (Fig. 4A). Moreover, BIM did not block AMPH-mediated DAT surface losses (Fig. 4A). BIM’s inability to block AMPH-mediated DAT sequestration was not due to lack of intrinsic activity, as BIM significantly blocked phorbol ester-mediated DAT downregulation in uptake experiments performed in parallel (Fig. 4B), and was fully effective in blocking phorbol ester-induced DAT surface losses (Fig. 4C). These results strongly suggest that AMPH-induced DAT surface losses occur independent of PKC activity.

Fig. 4.

PKC activity is not required for AMPH-stimulated DAT surface losses. (A) Cell surface biotinylation. DAT-PC12 cells were pretreated with either vehicle or 1 mM BIM I, 20 min, 37 °C, followed by treatment ±5 µM AMPH, 30 min, 37 °C proteins were labeled and isolated by cell surface biotinylation and streptavidin pulldown as described in Section 2. Top: representative immunoblot indicating surface (S) and intracellular (I) DAT fractions following treatment with either vehicle, 5 µM AMPH, 1 µM BIM or 1 µM BIM/5 µM AMPH. Bottom: average data. Bars represent percent vehicle surface levels ± SEM following the indicated drug treatments. Asterisks indicate significant difference from vehicle-treated cells: *p < 0.001, **p < 0.01; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test, n = 5. (B and C) BIM blocks PKC-induced DAT downregulation and surface losses. DAT-PC12 cells were pretreated with either vehicle or 1 µM BIM I, 20 min, 37 °C, followed by treatment with ±1 µM phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA), 30 min, 37 °C. [3H]DA uptake was measured as described in Section 2 and surface proteins were labeled and isolated by cell surface biotinylation as described in Section 2. (B) DA uptake assay. Bars represent percent specific DA uptake ± SEM as compared to vehicle-treated cells. *Significant difference from vehicle p < 0.001, **significant difference from PMA p < 0.01; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test, n = 4. (C) Surface biotinylation. Top: representative immunoblot indicating surface (S) and intracellular (I) DAT fractions following the indicated treatments. Bottom: averaged data. Bars represent percent total surface DAT ± SEM following the indicated drug treatments. *Significant difference from vehicle p < 0.05, **significant difference from PMA p < 0.05; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test, n = 3.

4. Discussion

The majority of previous studies demonstrating AMPH-mediated DAT sequestration were performed in non-neuronal heterologous expression systems. In the current study, we used the neuroendocrine pheochromocytoma cell line, PC12, to investigate mechanisms required for AMPH-mediated DAT trafficking. Although PC12 cells do not endogenously express appreciable levels of DAT, they express the rat NE transporter (rNET), DAT’s closest SLC6 homolog. Since we are using a pooled, stably transfected cell line, we were concerned that overexpression may mask a potential role for PKC in AMPH-induced DAT trafficking. However, hDAT expression levels in our DAT-PC12 cells are comparable to those of the endogenously expressed rNET, as determined by [3H]DA uptake assay (Navaroli and Melikian, unpublished results), suggesting that overexpression is not a likely concern in our studies. Similar to results obtained in non-neuronal cell lines (Garcia et al., 2005; Kahlig and Galli, 2003; Kahlig et al., 2006; Wei et al., 2007), we observed a 19.3% decrease in wild type DAT surface levels following 30 min AMPH exposure. AMPH-stimulated DAT sequestration did not rely on DAT residues 587–590, which are necessary for PKC-mediated DAT sequestration (Boudanova and Melikian, unpublished results) suggesting that AMPH and PKC-induced DAT trafficking may rely on independent mechanisms.

Although AMPH-induced DAT sequestration has been well described, the kinetic underpinnings that modulate DAT trafficking in response to AMPH have not been extensively investigated. Endocytosis assays revealed that AMPH enhanced DAT internalization by 58.7 ± 18.3% (Fig. 2). AMPH also significantly increased the endocytic rate of the DAT 587–590(4A) mutant, which does not exhibit increased endocytosis in response to PKC activation (Fig. 2). These results demonstrate, for the first time, that AMPH accelerates DAT’s endocytic rate. Moreover, taken with our surface biotinylation results (Fig. 1), these results also strongly suggest that PKC-sensitive DAT residues are not required for AMPH-mediated DAT sequestration.

The surface to intracellular distribution of any protein (X) is a direct reflection of its endocytic (kendo) and exocytic (kexo) rates, as defined by the relationship:

| (1) |

Since DAT basally internalizes and recycles back to the plasma membrane, AMPH-induced changes in DAT surface levels could arise from increased endocytosis, decreased recycling, or both. AMPH markedly decreased DAT recycling rates (Fig. 3A). Reduced DAT delivery to the plasma membrane is not likely due to acute AMPH effects on DAT biosynthesis, as previous results from our laboratory demonstrated that biosynthetic delivery does not significantly contribute to DAT surface levels within a 3-h timeframe (Loder and Melikian, 2003). A recent trafficking study in striatal synaptosomes reported that AMPH transiently (<3 min) increases DAT surface delivery, after which recycling rates return to basal levels (Johnson et al., 2005a). Our data are not inconsistent with these findings, as our initial recycling timepoints begin after 5 min of AMPH exposure.

We also investigated whether AMPH globally blocked endocytic recycling. Endosomes are maintained at acidic pH levels by a vacuolar ATPase, and endocytic trafficking requires acidified endosomes (Mellman et al., 1986; van Weert et al., 1995). AMPH is a weak base that promotes loss of the synaptic vesicle proton gradient, leading to elevated cytosolic DA levels (Sulzer and Rayport, 1990; Sulzer et al., 2005). Thus, it is possible that AMPH could impart a weak base effect that would increase endosomal pH values and thereby perturb endocytic recycling non-specifically. We did not find this to be the case, however, as TfR recycling rates were unaffected by AMPH treatment (Fig. 3B), suggesting that AMPH effects on DAT recycling are specific, and that AMPH does not globally disrupt endocytic trafficking.

AMPH-stimulated DA efflux through DAT requires PKC activation (Cowell et al., 2000; Johnson et al., 2005b; Kantor and Gnegy, 1998; Kantor et al., 2001). We asked whether PKC activity is also required for AMPH-mediated DAT sequestration. Pretreating cells with the PKC inhibitor BIM I did not block AMPH-induced DAT sequestration (Fig. 4), suggesting that PKC activity is not required for AMPH-induced DAT losses from the cell surface. Taken together with our results that demonstrate AMPH-induced DAT losses in the PKC-insensitive DAT mutant 587–590(4A), we conclude that AMPH-mediated DAT sequestration occurs independent of both PKC activity and PKC-sensitive endocytic determinants.

What are the possible mechanisms mediating AMPH-stimulated endocytosis and AMPH-suppressed recycling? The plasma membrane SNARE protein, syntaxin 1A, is reported to interact with the amino terminus of several SLC6 transporters, including those for DA (Lee et al., 2004), 5-HT (Quick, 2002, 2003), GABA (Deken et al., 2000; Hansra et al., 2004; Horton and Quick, 2001) and NE (Dipace et al., 2007; Sung et al., 2003). In addition to intrinsically modulating transporter kinetics, NET/syntaxin 1A interactions dictate NET’s capacity to sequester in response to AMPH (Dipace et al., 2007). However, it is currently not certain whether NET/syntaxin interactions directly impact AMPH effects on internalization or recycling. A strong candidate mediating AMPH actions on DAT recycling rates is Protein kinase B (Akt). Akt activation plays a critical role in insulin-regulated GLUT4 delivery to the plasma membrane (Dugani and Klip, 2005; Ishiki and Klip, 2005; Whiteman et al., 2002). Recent studies indicate that decreased Akt activity decreases DAT surface levels (Garcia et al., 2005), and that AMPH decreases Akt activity in a manner that relies on CamKII activity (Wei et al., 2007) and AMPH translocation into the cytosol (Kahlig et al., 2006). Thus, AMPH-mediated decreases in Akt activity could account for the decreased DAT recycling we observed during AMPH exposure. Future studies will address this possibility in greater detail.

Acknowledgements

We thank Zachary Stevens for excellent technical assistance, and Drs William Kobertz and Andrew Tapper for helpful discussions. This work was funded by NIH grant DA15169 to H.E.M.

Footnotes

This article was published in an Elsevier journal. The attached copy is furnished to the author for non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the author’s institution, sharing with colleagues and providing to institution administration.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright

References

- Barker EL, Blakely RD. Norepinephrine and serotonin transporters: molecular targets of antidepressant drugs. In: Bloom FKD, editor. Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. New York: Raven; 1995. pp. 321–333. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DJ. Functional imaging studies on dopamine and motor control. J. Neural. Transm. 2001;108:1283–1298. doi: 10.1007/s007020100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson T, Bjorklund T, Kirik D. Restoration of the striatal dopamine synthesis for Parkinson’s disease: viral vector-mediated enzyme replacement strategy. Curr. Gene Ther. 2007;7:109–120. doi: 10.2174/156652307780363125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N-H, Reith MEA. Effects of locally applied cocaine, lidocaine, and various uptake blockers on monoamine transmission in the ventral tegmental area of freely moving rats: a microdialysis study on monoamine interrelationships. J. Neurochem. 1994;63:1701–1713. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63051701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen NH, Reith ME, Quick MW. Synaptic uptake and beyond: the sodium- and chloride-dependent neurotransmitter transporter family SLC6. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:519–531. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi L, Reith ME. Substrate-induced trafficking of the transporter in heterologously expressing cells and in rat striatal synaptosomal preparations. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;307:729–736. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.055095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JD, Braver TS, Brown JW. Computational perspectives on dopamine function in prefrontal cortex. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2002;12:223–229. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell RM, Kantor L, Hewlett GHK, Frey KA, Gnegy ME. Dopamine transporter antagonists block phorbol ester-induced dopamine release and dopamine transporter phosphorylation in striatal synaptosomes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000;389:59–65. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00828-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deken SL, Beckman ML, Boos L, Quick MW. Transport rates of GABA transporters: regulation by the N-terminal domain and syntaxin 1A. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:998–1003. doi: 10.1038/79939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipace C, Sung U, Binda F, Blakely RD, Galli A. Amphetamine induces a calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-dependent reduction in norepinephrine transporter surface expression linked to changes in syntaxin 1a/transporter complexes. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007;71:230–239. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugani CB, Klip A. Glucose transporter 4: cycling, compartments and controversies. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:1137–1142. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fog JU, Khoshbouei H, Holy M, Owens WA, Vaegter CB, Sen N, Nikandrova Y, Bowton E, McMahon DG, Colbran RJ, Daws LC, Sitte HH, Javitch JA, Galli A, Gether U. Calmodulin kinase II interacts with the dopamine transporter C terminus to regulate amphetamine-induced reverse transport. Neuron. 2006;51:417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia BG, Wei Y, Moron JA, Lin RZ, Javitch JA, Galli A. Akt is essential for insulin modulation of amphetamine-induced human dopamine transporter cell-surface redistribution. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;68:102–109. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.009092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gether U, Andersen PH, Larsson OM, Schousboe A. Neurotransmitter transporters: molecular function of important drug targets. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2006;27:375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulley JM, Doolen S, Zahniser NR. Brief, repeated exposure to substrates down-regulates dopamine transporter function in Xenopus oocytes in vitro and rat dorsal striatum in vivo. J. Neurochem. 2002;83:400–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansra N, Arya S, Quick MW. Intracellular domains of a rat brain GABA transporter that govern transport. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4082–4087. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0664-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holton KL, Loder MK, Melikian HE. Nonclassical, distinct endocytic signals dictate constitutive and PKC-regulated neurotransmitter transporter internalization. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:881–888. doi: 10.1038/nn1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton N, Quick MW. Syntaxin 1A up-regulates GABA transporter expression by subcellular redistribution. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2001;18:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiki M, Klip A. Minireview: recent developments in the regulation of glucose transporter-4 traffic: new signals, locations, and partners. Endocrinology. 2005;146:5071–5078. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LAA, Furman CA, Zhang M, Guptaroy B, Gnegy ME. Rapid delivery of the dopamine transporter to the plasmalemmal membrane upon amphetamine stimulation. Neuropharmacology. 2005a;49:750–758. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LAA, Guptaroy B, Lund D, Shamban S, Gnegy ME. Regulation of amphetamine-stimulated dopamine efflux by protein kinase C {beta} J. Biol. Chem. 2005b;280:10914–10919. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413887200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlig KM, Galli A. Regulation of dopamine transporter function and plasma membrane expression by dopamine, amphetamine, and cocaine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;479:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlig KM, Lute BJ, Wei Y, Loland CJ, Gether U, Javitch JA, Galli A. Regulation of dopamine transporter trafficking by intracellular amphetamine. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;70:542–548. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.023952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor L, Gnegy ME. Protein kinase C inhibitors block amphet-amine-mediated dopamine release in rat striatal slices. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;284:592–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor L, Hewlett GHK, Park YH, Richardson-Burns SM, Mellon MJ, Gnegy ME. Protein kinase C and intracellular calcium are required for amphetamine-mediated dopamine release via the norepinephrine transporter in undifferentiated PC12 cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;297:1016–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Westphalen R, Callahan B, Hatzidimitriou G, Yuan J, Ricaurte GA. Toward development of an in vitro model of methamphetamine-induced dopamine nerve terminal toxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;293:625–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaHoste GJ, Henry BL, Marshall JF. Dopamine D1 receptors synergize with D2, but not D3 or D4, receptors in the striatum without the involvement of action potentials. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:6666–6671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06666.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH, Kim MY, Kim DH, Lee YS. Syntaxin 1A and receptor for activated C kinase interact with the N-terminal region of human dopamine transporter. Neurochem. Res. 2004;29:1405–1409. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000026404.08779.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LB, Chen N, Ramamoorthy S, Chi L, Cui XN, Wang LC, Reith ME. The role of N-glycosylation in function and surface trafficking of the human dopamine transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:21012–21020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311972200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loder MK, Melikian HE. The dopamine transporter constitutively internalizes and recycles in a protein kinase C-regulated manner in stably transfected PC12 cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:22168–22174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301845200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melikian HE. Neurotransmitter transporter trafficking: endocytosis, recycling, and regulation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;104:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melikian HE, Buckley KM. Membrane trafficking regulates the activity of the human dopamine transporter. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:7699–7710. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-07699.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellman I, Fuchs R, Helenius A. Acidification of the endocytic and exocytic pathways. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1986;55:663–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.003311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson N. The family of Na+/Cl− neurotransmitter transporters. J. Neurochem. 1998;71:1785–1803. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71051785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick MW. Role of syntaxin 1A on serotonin transporter expression in developing thalamocortical neurons. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2002;20:219–224. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(02)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick MW. Regulating the conducting states of a mammalian serotonin transporter. Neuron. 2003;40:537–549. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00605-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MB. Regulated trafficking of neurotransmitter transporters: common notes but different melodies. J. Neurochem. 2002;80:1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Baumann MH. Monoamine transporters and psychostimulant drugs. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;479:23–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval V, Hanson GR, Fleckenstein AE. Methamphetamine decreases mouse striatal dopamine transporter activity: roles of hyperthermia and dopamine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000;409:265–271. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00871-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval V, Riddle EL, Ugarte YV, Hanson GR, Fleckenstein AE. Methamphetamine-induced rapid and reversible changes in dopamine transporter function: an in vitro model. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:1413–1419. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01413.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders C, Ferrer JV, Shi L, Chen J, Merrill G, Lamb ME, Leeb-Lundberg LM, Carvelli L, Javitch JA, Galli A. Amphet-amine-induced loss of human dopamine transporter activity: an internalization-dependent and cocaine-sensitive mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:6850–6855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110035297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarponi M, Bernardi G, Mercuri NB. Electrophysiological evidence for a reciprocal interaction between amphetamine and cocaine-related drugs on rat midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:593–598. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sora I, Hall FS, Andrews AM, Itokawa M, Li XF, Wei HB, Wichems C, Lesch KP, Murphy DL, Uhl GR. Molecular mechanisms of cocaine reward: combined dopamine and serotonin transporter knockouts eliminate cocaine place preference. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:5300–5305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091039298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorkina T, Hoover BR, Zahniser NR, Sorkin A. Constitutive and protein kinase C-induced internalization of the dopamine transporter is mediated by a clathrin-dependent mechanism. Traffic. 2005;6:157–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Rayport S. Amphetamine and other psychostimulants reduce pH gradients in midbrain dopaminergic neurons and chromaffin granules: a mechanism of action. Neuron. 1990;5:797–808. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90339-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Sonders MS, Poulsen NW, Galli A. Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: a review. Prog. Neurobiol. 2005;75:406–433. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung U, Apparsundaram S, Galli A, Kahlig KM, Savchenko V, Schroeter S, Quick MW, Blakely RD. A regulated interaction of syntaxin 1A with the antidepressant-sensitive norepinephrine transporter establishes catecholamine clearance capacity. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:1697–1709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01697.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Weert AW, Dunn KW, Gueze HJ, Maxfield FR, Stoorvogel W. Transport from late endosomes to lysosomes, but not sorting of integral membrane proteins in endosomes, depends on the vacuolar proton pump. J. Cell Biol. 1995;130:821–834. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.4.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayment HK, Schenk JO, Sorg BA. Characterization of extracellular dopamine clearance in the medial prefrontal cortex: role of monoamine uptake and monoamine oxidase inhibition. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:35–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00035.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Williams JM, Dipace C, Sung U, Javitch JA, Galli A, Saunders C. Dopamine transporter activity mediates amphetamine-induced inhibition of Akt through a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II-dependent mechanism. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007;71:835–842. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman EL, Cho H, Birnbaum MJ. Role of Akt/protein kinase B in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;13:444–451. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00662-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JM, Kalasinsky KS, Levey AI, Bergeron C, Reiber G, Anthony RM, Schmunk GA, Shannak K, Haycock JW, Kish SJ. Striatal dopamine nerve terminal markers in human, chronic methamphetamine users. Nat. Med. 1996;2:699–703. doi: 10.1038/nm0696-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahniser NR, Doolen S. Chronic and acute regulation of Na+/Cl− dependent neurotransmitter transporters: drugs, substrates, presynaptic receptors, and signaling systems. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001;92:21–55. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]