Abstract

Purpose

Zinc has been reported to ameliorate hematologic side effects and improve liver function. In addition to its various effects, zinc supplementation in chronic hepatitis C patients with genotype 1b of high viral load enhanced the response to interferon (IFN) monotherapy. This study was aimed at clarifying whether zinc could improve hematologic side effects, improve liver function, and enhance the response to therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with pegylated-interferon (PEG-IFN) plus ribavirin (RBV).

Methods

The 32 patients enrolled in the study were randomly divided into two groups: a PEG-IFN-α2b plus RBV with zinc group (PEG/RBV + zinc, n = 16) and a PEG-IFN-α2b plus RBV group (PEG/RBV, n = 16). HCV-RNA, serum zinc, ALT, white blood cell, red blood cell, platelet, and hemoglobin (Hb) levels were examined.

Results

Serum zinc levels were significantly higher in the PEG/RBV with zinc group than in the PEG/RBV without zinc group at 4, 8, and 12 weeks. No significant differences were observed in the clearance of HCV-RNA between the two groups. The outcome of the treatment was similar; results of laboratory examinations including ALT before, during, and after therapy revealed no significant differences between the two groups at any point in all items except serum zinc levels. A sustained virological response rate was observed in 50.0% in the PEG/RBV with zinc group and 43.8% in the PEG/RBV without zinc group, with no significant difference between the two groups.

Conclusions

The study demonstrated no evidence that zinc ameliorates hematologic side effects, improves liver function, and enhances the response to the therapy in chronic hepatitis C receiving PEG-IFN-α2b plus RBV.

Keywords: Pegylated-interferon, Ribavirin, Zinc, Hematologic side effect, Chronic hepatitis C

Introduction

Interferon (IFN) is an essential component in the treatment of HCV infection. Treatment with IFN alone is, however, generally associated with a sustained virologic response in fewer than 20% of patients [1–3]. Pegylated-interferon (PEG-IFN) given once a week with ribavirin (RBV) administered orally is more effective than a regimen of standard IFN given three times a week [4]. Hematologic side effects (anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia) of PEG-IFN plus RBV therapy are commonly encountered during antiviral therapy for HCV [5]. One strategy for these side effects is dose reduction, including discontinuation, of PEG-IFN plus RBV, which diminishes the efficacy of the optimal treatment regimen for HCV and may exert a negative impact on sustained virological response. A decrease in thrombocytes and leukocytes is the most frequently reported hematologic abnormality resulting from treatment with PEG-IFN plus RBV, and may be the most marked side effect. In addition, a decrease in hemoglobin (Hb) and red blood cells (RBC) associated with fatigue may impair patients’ quality of life.

On the other hand, patients with chronic liver disease show impaired trace-element metabolisms; namely, high levels of iron and copper and low levels of zinc, selenium, phosphorus, calcium, and magnesium [6]. Of these trace elements, zinc is a constituent of a number of enzymes and, as such, is involved in a large number of metabolic processes. Mild to severe zinc deficiency disrupts several biological functions, such as gene expression, protein synthesis, immunity, skeletal growth and maturation, gonad development, pregnancy outcomes, taste perception, and appetite [7, 8].

Zinc has been reported to ameliorate hematologic side effects and improve liver function in IFN monotherapy [9, 10]. In addition to its various effects, zinc supplementation in chronic hepatitis C patients with genotype 1b of high viral load enhanced the response to IFN monotherapy [10]. This study aimed to assess whether zinc could counter the decrease in white blood cells (WBC), RBC, platelets, and Hb and enhance the response to IFN and improve liver function in patients with chronic hepatitis C receiving PEG-IFN plus RBV.

Patients and methods

Between December 2004 and July 2005, the 32 patients included in this study demonstrated high viral loads of serum HCV-RNA of genotype 1b; they had been diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C on the basis of abnormal serum ALT for at least 6 months, and with positive HCV-RNA assessed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). None of the patients were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen or other liver diseases (autoimmune hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease). All the patients received a regimen of PEG-IFNα-2b (Peg-Intron, Schering-Plough, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) (1.5 μg/kg/week, subcutaneously) in combination with RBV (Rebetol, Schering-Plough, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) (600–1000 mg/day) for 48 weeks. RBV was administered at a dose of 600 mg/day (3 capsules) in patients weighing <60 kg, 800 mg/day (4 capsules) in patients weighing <80 kg, and 1000 mg/day (5 capsules) in those weighing >80 kg. We conducted clinical trials with PEG-IFN-α2b plus RBV with or without polaprezinc (Promac, Zeria Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan), a zinc-containing drug that was originally developed as a mucosal defender, in 32 patients with chronic hepatitis C. Informed consent was obtained from all patients enrolled in the study after a thorough explanation of the aims, risks, and benefits of the therapy. The patients were randomly divided into two groups: a PEG-IFN plus ribavirin with zinc group (PEG/RBV + zinc) and a PEG-IFN plus ribavirin without zinc group (PEG/RBV). The former (n = 16) was treated with PEG-IFN-α2b plus ribavirin and administered polaprezinc 75 mg (containing 17 mg zinc) orally twice a day for 48 weeks. The latter (n = 16) received PEG-IFN-α2b plus ribavirin. Serum HCV-RNA, ALT, WBC, RBC, platelets, and Hb were examined before, at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks, and after every 4 weeks until 24 weeks after the combination therapy. Serum zinc levels were examined before and after every 4 weeks until 24 weeks.

HCV-RNA was quantified using the Amplicor HCV Monitor v 2.0 assay (Roche Molecular Systems Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA) with a lower detection limit of 50 IU/mL at baseline and at 12, 24, and 24 weeks after cessation of IFN administration.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistically significant differences in outcomes between the two regimens were assessed by the χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test or Student’s t test, and the Mann–Whitney test. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

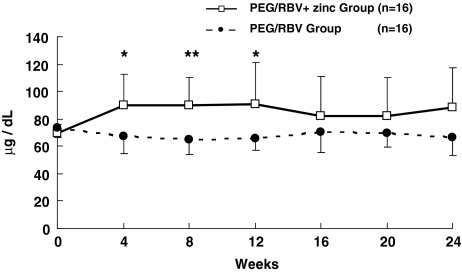

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences (NS) between the two groups. The zinc level at 4 weeks of administration was 89.8 ± 23.0 μg/dl in the PEG/RBV + zinc group and 67.1 ± 12.6 μg/dl in the PEG/RBV group (p < 0.005); 89.8 ± 20.9 and 65.0 ± 10.7 μg/dl at 8 weeks (p < 0.001); 90.9 ± 30.2 and 65.4 ± 8.2 μg/dl at 12 weeks (p < 0.005); 82.1 ± 28.7 and 70.4 ± 14.5 μg/dl at 16 weeks; 82.4 ± 28.2 and 70.0 ± 10.3 μg/dl at 20 weeks; and 88.4 ± 29.0 and 66.7 ± 13.9 μg/dl at 24 weeks (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients

| PEG/RBV + zinc group | PEG/RBV group | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 10 | 9 | NS |

| Female | 6 | 7 | NS |

| Age (years) | 56.8 ± 7.2 | 56.7 ± 12.9 | NS |

| Body weight (kg) | 60.2 ± 11.1 | 59.3 ± 11.1 | NS |

| HCV-RNA (KIU/ml) | 1286.3 ± 1157.3 | 2038.0 ± 1561.2 | NS |

| Zn (μg/dl) | 69.4 ± 6.5 | 73.9 ± 7.5 | NS |

| WBC (μl) | 4781.3 ± 1458.4 | 4850.0 ± 1730.9 | NS |

| RBC (×104/μl) | 435.1 ± 49.1 | 449.4 ± 55.4 | NS |

| Platelets (×104/μl) | 16.4 ± 5.5 | 14.7 ± 4.7 | NS |

| Hb (g/dl) | 13.7 ± 1.6 | 14.2 ± 1.6 | NS |

| ALT (IU/l) | 45.6 ± 39.3 | 48.2 ± 26.9 | NS |

Data are expressed as means ± SD; NS, not significant

Fig. 1.

Changes in Zn level in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with PEG-IFN-α2b plus ribavirin. Zn level in the PEG/RBV + zinc group (open square) and in the PEG/RBV group (solid circle). Data are given as mean ± SD. * p < 0.005; ** p < 0.001

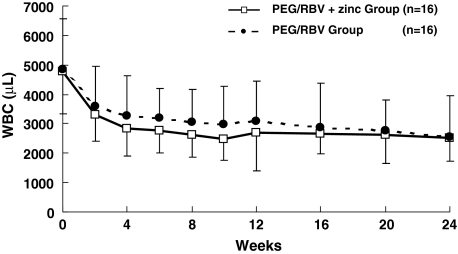

The WBC count at 2 weeks of administration was 32.9 ± 8.9 (×102)/μl in the PEG/RBV + zinc group and 36.1 ± 13.4 (×102)/μl in the PEG/RBV group, with NS between the two groups. There was NS between the two groups at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 weeks of treatment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Changes in WBC count in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with PEG-IFN-α2b plus. WBC count in the PEG/RBV + zinc group (open square) and in the PEG/RBV group (solid circle). Data are given as mean ± SD

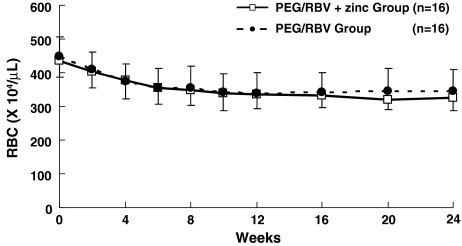

The RBC count at 2 weeks of administration was 403.5 ± 47.2 (×104)/μl in the PEG/RBV + zinc group and 410.9 ± 51.6 (×104)/μl in the PEG/RBV group, with NS between the two groups. There was NS between the two groups at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 weeks of treatment (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Changes in RBC count in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with PEG-IFN-α2b plus ribavirin. RBC count in the PEG/RBV + zinc group (open square) and in the PEG/RBV group (solid circle). Data are given as mean ± SD

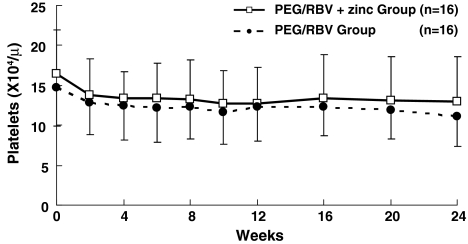

Platelet count at 2 weeks of administration was 13.8 ± 4.6 (×104)/μl in the PEG/RBV + zinc group and 12.8 ± 4.0 (×104)/μl in the PEG/RBV group, with NS between the two groups. There was NS between the two groups at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 weeks of treatment (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Changes in platelet count in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with PEG-IFN-α2b plus ribavirin. Platelet count in the PEG/RBV + zinc group (open square) and in the PEG/RBV group (solid circle). Data are given as mean ± SD

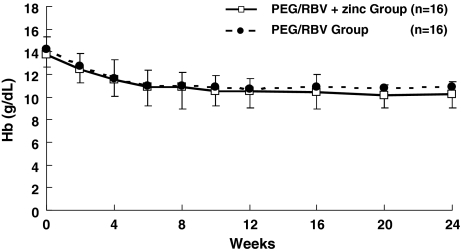

Hb concentration at 2 weeks of administration was 12.5 ± 1.4 g/dl in the PEG/RBV + zinc group and 12.8 ± 1.5 g/dl in the PEG/RBV group, with NS between the two groups. There was NS between the two groups at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 weeks (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Changes in Hb concentration in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with PEG-IFN-α2b plus ribavirin. Hb value in the PEG/RBV + zinc group (open square) and in the PEG/RBV group (solid circle). Data are given as mean ± SD

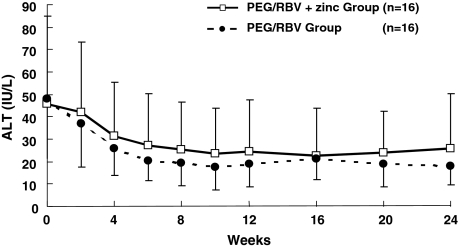

Serum ALT level at 2 weeks of administration was 42.1 ± 31.1 IU/l in the PEG/RBV + zinc group and 36.8 ± 19.1 IU/l in the PEG/RBV group, with NS between the two groups. There was NS between the two groups at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 weeks of treatment (Fig. 6). The HCV-RNA response rate at 12 weeks of IFN administration (EVR) was 31.3% (5/16) in the PEG/RBV + zinc group and 50.0% (8/16) in the PEG/RBV group, and 62.5% (10/16) in the PEG/RBV + zinc group and 68.8% (11/16) in the PEG/RBV group at 24 weeks, with NS between the two groups. A sustained virological response (SVR) rate was observed in 50.0% (8/16) in the PEG/RBV with zinc group and 43.8% (7/16) in the PEG/RBV without zinc group, with NS between the two groups (Table 2).

Fig. 6.

Changes in ALT level in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with PEG-IFN-α2b plus ribavirin. ALT level in the PEG/RBV + zinc group (open square) and in the PEG/RBV group (solid circle). Data are given as mean ± SD

Table 2.

Response rate of IFN therapy

| PEG/RBV + zinc group | PEG/RBV group | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| At 12th week | 31.3% (5/16) | 50.0% (8/16) | NS |

| At 24th week | 62.5% (10/16) | 68.8% (11/16) | NS |

| SVR | 50.0% (8/16) | 43.8% (7/16) | NS |

Data are expressed as means ± SD; NS, not significant

The outcome of the treatment was similar, with NS between the two groups at any point in all items except serum zinc levels.

Discussion

We assessed whether zinc could counter decreases of WBC, RBC, platelets, and Hb in HCV-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C receiving PEG-IFN plus RBV with zinc. Hematologic side effects (leukopenia and thrombocytopenia and anemia) of PEG-IFN plus RBV therapy are commonly encountered during antiviral therapy for HCV [5]. To overcome these side effects, dose reduction of PEG-IFN, RBV, or both are carried out. The reduction, including discontinuation, diminishes the efficacy of the optimal treatment regimen for HCV and may have a negative effect on sustained virological response. Especially, thrombocytopenia is the most frequently reported hematologic abnormality resulting from treatment with PEG-IFN plus RBV, and it may be the most dominant side effect. In addition, anemia associated with fatigue may impair patients’ quality of life. Combination therapy with PEG-IFN and RBV causes anemia frequently.

Zinc has been studied for its antiviral effect in HIV, rhinovirus, and herpes virus [11–14]. In addition to its anti-inflammatory effect, zinc exerts an antioxidant effect and induces metallothionein (MT), which has radical scavenging and immunomodulatory properties [12, 15].

Owing to these pharmacological mechanisms, a zinc supply may have many beneficial effects in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Zinc not only ameliorates hematologic side effects but also improves liver function [9, 10]. Polaprezinc, a synthetic agent, N-(3-aminopropionyl)-l-histidinate zinc, is a chelate compound developed for ulcer healing [16, 17]. Zinc contained in orally administered polaprezinc is absorbed, however, and leads to a rise in serum concentrations of zinc [18]. In this respect, absorption of polaprezinc is more favorable than other zinc-containing derivatives, such as zinc sulfate. Takagi et al. demonstrated that zinc supplementation enhanced the response to IFN monotherapy [9]. On the other hand, Suzuki et al. reported that zinc did not improve liver function and enhance the response to the IFN plus RBV therapy except for lower incidence of gastrointestinal side effects [19]. Although plasma levels of zinc were significantly increased, we were not able to demonstrate that the administration of polaprezinc ameliorates hematologic side effects such as thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and anemia and that it improves liver function in HCV-infected patients receiving combination PEG-IFN + RBV with zinc therapy compared with patients receiving PEG-IFN + RBV therapy. One possible reason for these results may be the paucity of cases studied. Another reason may be that the dosage of polaprezinc 75 mg (containing 17 mg zinc) was insufficient for ameliorating the hematologic side effects. Nagamine et al. tried with 300 mg of zinc sulfate (containing 68 mg of zinc) a day orally in IFN with zinc therapy and without serious adverse effects [9]. We propose, therefore, to increase the dosage of polaprezinc twofold in future trials. This study fell short of demonstrating that zinc ameliorates hematologic side effects (anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia) and improves liver function in HCV-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C receiving PEG-IFN-α2b plus RBV together with zinc.

Takagi et al. found that zinc supplementation enhances the response to IFN therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C [10]. Our results did not show improvement in liver function or increase in SVR rate to improving liver function and increasing virological response rate to PEG-IFN + zinc therapy in HCV genotype 1 with high viral loads. Whereas Takagi et al. dealt with 75 patients in IFN monotherapy, we enrolled only 32 patients. Consequently, further studies on a larger number of patients are indicated for the evaluation of the double dosage of polaprezinc.

In conclusion, the study demonstrated no evidence that zinc ameliorates hematologic side effects, improves liver function, and enhances the response to the therapy in chronic hepatitis C receiving PEG-IFN-α2b plus RBV.

References

- 1.Carithers RL Jr, Emerson SS. Therapy of hepatitis C: meta-analysis of interferon alfa-2b trials. Hepatology. 1997;26:83S–88S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Thevenot T, Regimbeau C, Ratziu V, Leroy V, Opolon P, Poynard T. Meta-analysis of interferon randomized trials in the treatment of viral hepatitis C in naive patients: 1999 update. J Viral Hepatol. 2001;8:48–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Farrell GC. Therapy of hepatitis C: interferon alfa-nl trials. Hepatology. 1997;26:96S–100S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Zeuzem S, Feinman SV, Rasenack J, Heathcote EJ, Lai MY, Gane E, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1666–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Collantes RS, Younossi ZM. The use of growth factors to manage the hematologic side effects of peg-interferon alfa and ribavirin. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:9S–13S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Loguercio C, De Girolamo V, Federico A, Feng SL, Cataldi V, Del Vecchio Blanco C, et al. Trace elements and chronic liver diseases. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 1997;11:158–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Aggett PJ. Severe zinc deficiency. In: Millis CF, editor. Zinc in human biology. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1989. p. 259–79.

- 8.Umeta M, West CE, Haidar J, Deurenburg P, Hautvast JG. Zinc supplementation and stunted infants in Ethiopia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355:2021–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Nagamine T, Takagi H, Hashimoto Y, Takayama H, Shimoda R, Nomura N, et al. The possible role of zinc and metallothionein in the liver on the therapeutic effect of IFN-α to hepatitis C patients. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1997;58:65–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Takagi H, Nagamine T, Abe T, Takayama K, Sato K, Otsuka T, et al. Zinc supplementation enhances the response to interferon therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepatol. 2001;8:367–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Novick SG, Godfrey JC, Pollack RL, Wilder HR. Zinc-induced suppression of inflammation in the respiratory tract, caused by infection with human rhinovirus and other irritants. Med Hypotheses. 1997;49:347–57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Powell SR. The antioxidant properties of zinc. J Nutr. 2000;130:1447s–54s. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Haraguchi Y, Sakurai H, Hussain S, Anner BM, Hoshino H. Inhibition of HIV-1 infection by zinc group metal compounds. Antiviral Res. 1999;43:123–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kumel G, Schrader S, Zentgraf H, Brendel M. Therapy of banal HSV lesions: molecular mechanisms of the antiviral activity of zinc sulfate. Hautarzt. 1991;42:439–45. [PubMed]

- 15.Prasad AS. Zinc and immunity. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;188:63–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Arakawa T, Satoh H, Nakamura A, Nebiki H, Fukuda T, Sakuma H, et al. Effects of zinc l-carnosine on gastric mucosal and cell damage caused by ethanol in rats. Correlation with endogenous prostaglandin E2. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:559–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Miyoshi A, Matsuo H, Miwa G, Nakajima M. Clinical evaluation of Z-103 in the treatment of gastric ulcer. Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 1992;20:181–97.

- 18.Sano H, Furuta S, Toyama S, Miwa M, Ikeda Y, Suzuki M, Sato H, Matsuda K. Study on the metabolic fate of catena-(S)-[μ-[N α-(3-aminopropinyl)histidinato(2-)-N1, N2, O:N τ]-zinc]. 1st communication: absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion after single administration to rats. Arzneimittelforschung. 1991;41:965–75. [PubMed]

- 19.Suzuki H, Takagi H, Sohara N, Kanda D, Kakizaki S, Sato K, et al. Triple therapy of interferon and ribavirin with zinc supplementation for patients with chronic hepatitis C: a randomized controlled clinical trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1265–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]