Abstract

Prediction of mortality of patients with cirrhosis of liver, a common and potentially fatal disease, is important for timely listing of patients for liver transplantation. The Child–Pugh scoring system has been widely used for predicting the outcome of liver cirrhosis. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score has recently become popular for prediction of short-term mortality for organ allocation. A few studies that evaluated artificial neural network (ANN)-based model for prediction of outcome of cirrhosis of liver in terms of mortality have consistently shown it to be superior to Child–Pugh scoring and logistic regression-based models; it is worth noting that MELD score is also derived using the logistic regression model. Due to the inherent ability of neural network-based systems in identifying complex nonlinear interactions, ANN-based models are expected to perform better than most linear models, such as regression-based models. More studies are needed on ANN-based models for prediction of mortality of patients with cirrhosis of liver and its value in prioritization of organ allocation for treatment of patients with cirrhosis of liver.

Keywords: Neural network, Outcome prediction, Liver transplantation, Liver disease, Child–Pugh score, MELD score

Introduction

Cirrhosis of liver is a common health problem and results in significant morbidity and mortality. In the past, treatment of cirrhosis was mostly supportive and directed toward management of complications of this disease. Liver transplantation, available in most developed countries, has changed the management and outcome of patients with cirrhosis of liver [1]. However, limited availability of organ in the face of large demand leads to long waiting lists [2]. In the United States alone, there are currently more than 90,000 patients waiting for liver transplantation. Therefore, patients may die even before liver transplantation is done or have poor outcome despite transplantation owing to delay in performing the operation. Prediction of mortality from cirrhosis is important in planning the timing of liver transplantation in the face of limited availability of organ and the high cost of medical care of these patients. The need for a suitable method of prediction of mortality from cirrhosis from the perspective of liver transplantation has been emphasized [3] so that the patient likely to live shorter gets the organ earlier than a patient who would live longer. This is also important for avoiding futile transplantation with consequent inappropriate increase in demand on limited organ pool and cost of health care. When multiple and diverse factors are likely to influence decision making, computer-based decision support systems such as neural networks are often helpful in arriving at or supplementing a correct decision by the clinicians [4, 5]. Pugh’s modification of Child’s scoring system is one of the most widely used scoring systems for prediction of mortality from cirrhosis [6]. Limitations of this scoring system for deciding timings of liver transplantation include limited discriminative ability, variability in measurement of clinical and laboratory determinants [7] of this scoring system and, importantly, limited ability to predict short-term mortality. Several other scoring systems have been described that attempt to evaluate prognosis of patients with cirrhosis of liver (Table 1) [8–19]. However, none of these are applied widely in clinical practice because of their limited predictive ability and unacceptable complexity. Recently, the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score has been adopted to measure disease severity, outcome, and as a basis of determination of organ allocation policies [13, 28–32]. Although the MELD score has become very popular within a short time after its introduction [7, 19, 33, 34], it is not free from flaws. The MELD score is calculated using serum bilirubin, creatinine, and international normalized ratio (INR). Other major complications of cirrhosis such as refractory ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, encephalopathy, and variceal bleeding failed to improve the prognostic value of the MELD scoring system. Furthermore, several comorbid conditions that often influence the mortality of patients with serious illnesses are not taken into account while evaluating prognosis using the MELD scoring system [35].

Table 1.

Overview of different scoring systems of prediction of outcome of patients with cirrhosis of the liver

| Risk score | Input variables | Primary outcome | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTP score 1972 | Bilirubin, prothrombin time, ascites, albumin, hepatic encephalopathy | Operative risk | Easy to use. Lack of objectivity in measuring clinical and laboratory variables. Floor and ceiling limitation: lack of discriminative power | [20] |

| Prognostic index of Christensen 1989 | Initial presentation, ascites, serum creatinine, prothrombin index | 1- and 5-year survival | Predicting survival in patients with cirrhosis who have a first episode of gastrointestinal bleeding and/or coma | [21] |

| Prognostic index 1993 | CTP score, mid-arm muscle circumference, serum urea, and red blood cell MCV | 1- and 2-year survival | Patients with HCC, hemochromatosis, and acute bleeding excluded. Not validated | [22] |

| Prognostic index of Gatta 1994 | Ascites, HCC, variceal bleeding, hematemesis at presentation, gender, serum creatinine, bilirubin, and prothrombin index | Short-term survival (40 days) | Applicable to patients with cirrhosis and UGI bleeding | [23] |

| Erasme prognostic score 1997 | Hepatic encephalopathy, serum alkaline phosphatase, serum total bilirubin, serum cholinesterase, serum total bile acids | 1-year survival | May be better than CTP. Not validated | [24] |

| Prognostic index of Bustamante 1999 | Gender, serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, potassium, BUN and prothrombin activity | 1- and 3-year survival | For evaluating patients with hepatic encephalopathy associated with cirrhosis | [25] |

| Emory score 2000 | Variceal hemorrhage requiring emergent TIPS, ALT, bilirubin, and pre-TIPS encephalopathy | 30-day mortality | For prediction of mortality after TIPS | [26] |

| MELD score 2001 | Bilirubin, creatinine, and INR | Mortality | Widely used for liver transplant allocation. Lack of objectivity in measuring laboratory parameters. | [27] |

Abbreviations: CTP, Child–Turcotte–Pugh; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; UGI, upper gastrointestinal; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; MELD, Model for End-stage Liver Disease; INR, international normalized ratio

Critical overview of currently popular scoring systems

The two most commonly used prognostic models are the Child–Turcotte–Pugh score (CTP) [20] and the more recently described MELD score [27]. Child and Turcotte in 1964 empirically developed a model to risk stratify patients undergoing shunt surgery for portal decompression [36] and this was subsequently modified by Pugh in 1972 to develop a scoring system to minimize ambiguity inherent in the original description. The current CTP scoring system is based on five parameters: serum bilirubin level, serum albumin level, prothrombin time, and degree of ascites and encephalopathy [36]. The sum of the points for each of these five parameters gives the total score. Due to its simplicity and ease of use, the CTP system has been popular with clinicians for an approximate estimation of mortality in these patients. However, the CTP scoring system suffers from lack of objectivity in quantifying score components such as encephalopathy and degree of ascites, which are prone to marked inter-observer variations, its dependence on laboratory parameters such as albumin level and, in particular, prothrombin time, which is known to vary quite substantially from laboratory to laboratory. More important, the CTP scoring system suffers from a floor-and-ceiling effect in terms of the range of values that its scoring components can be assigned, and thus cannot be fine-tuned in its discriminatory capacity, which is crucially important for making important management decisions such as listing for liver transplantation. For example, this system cannot distinguish between patients with a serum bilirubin level of 4 mg/dl to one with a bilirubin of 30 mg/dl in terms of disease severity. Also, CTP scoring was designed to predict long-term mortality typically in years rather than short-term mortality in months, which is important for planning liver transplantation.

To overcome the limitations of the CTP scoring system, the MELD was prospectively developed and validated as a chronic liver disease severity scoring system that uses a patient’s laboratory values for serum bilirubin, creatinine, and the INR for prothrombin time to predict survival [27]. The revised model currently used by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) in prioritizing allocation of organs for liver transplantation is calculated according to the following formula: MELD = 3.8[Ln serum bilirubin (mg/dl)] + 11.2[Ln INR] + 9.6[Ln serum creatinine (mg/dl)] + 6.4, where Ln is the natural logarithm. Although the MELD score was originally described for selection of patients for TIPS, it has been most widely used for the allocation of liver transplants and a recent study documented the utility of MELD score in de-emphasizing waiting time as a major factor in prioritizing patients for liver transplantation and, in addition, use of MELD score is associated with increased transplantation rates without concomitant increased mortality rates [37]. Besides the above-mentioned indications, MELD score has also been evaluated for prediction of mortality associated with alcoholic hepatitis, hepatorenal syndrome, acute liver failure, sepsis in cirrhosis, and perioperative mortality in patients with chronic liver disease [27].

It should be noted that although the MELD score was devised primarily to overcome the limitations of the CTP scoring system, it does have its own limitations. The MELD score is subject to variability of laboratory measurements (such as bilirubin and creatinine levels), certain clinically important prognostic information, such as complications of portal hypertension, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), hepatopulmonary syndrome, and presence of select systemic metabolic disorders such as hyponatremia are not accounted for in the MELD score. Also, the MELD score was developed in a homogeneous cohort of patients waiting for liver transplantation and thus may not be applicable to a cohort of patients who are not being considered for liver transplantation because of either medical or socioeconomic reasons. The group that originally described MELD in a recent review did acknowledge that “MELD is by no means a perfect system” [27]. Indeed, a recent systemic review of studies comparing the accuracy of MELD vs. CTP score in transplantation settings pointed out that MELD score does not perform better than the CTP score for patients with cirrhosis on the waiting list and cannot predict post-transplant mortality [38].

The limitations of the widely used prognostic scoring systems have led on to search for other predictive indices and quite a few of them have been described in published information (Table 1). However, none of these alternative scoring systems are in widespread use given their inherent limitations of limited portability in the heterogeneous patient population. Many of them are cumbersome to use and most of them manifest worsening performance characteristics during external validation.

The requirement of any ideal scoring system for prediction of outcome in patients with chronic liver disease will be ease of use, portability in heterogeneous patient population both in and outside the context of liver transplantation and, also, its ability to discriminate different grades of severity of hepatic dysfunction over a broad continuum.

Can an ANN-based model overcome some of the shortcomings of conventional scoring systems for mortality prediction?

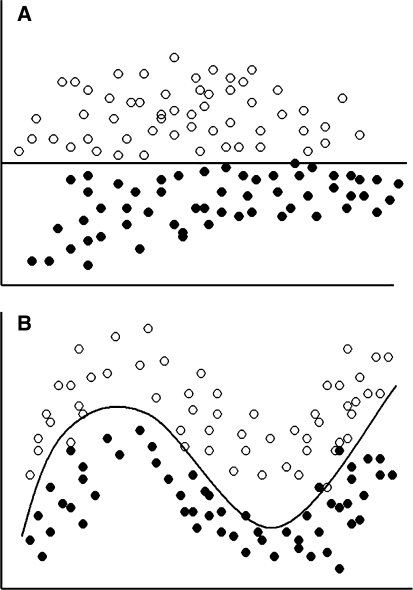

An ANN-based model has particular strength in terms of portability, unlike most of the predictive scoring systems, which are built on fixed regression models, the ANN based models are dynamic and do learn from experience. Regression models have their limitations as these are based on the presumption that all the data are linear, which is not the case in most biological situations (Fig. 1), [39]. While regression-derived models are fixed within the parameters of the original derivation cohort, an ANN-based model learns with experience and adapts to improve the error rate even when exposed to validation cohorts that may be substantially different from the derivation cohort. This is particularly suitable in predicting prognosis of patients with chronic liver disease of varying severity, different etiology, and changing clinical status.

Fig. 1.

While classifying patients based on two parameters, if the values of these parameters are widely apart and distributed in a such a manner that a straight line can be drawn to classify these patients into two groups (a), it would have been easy to do it using a linear modeling technique. However, in a biological situation, the values are distributed in a more haphazard manner (b). Still a line can be drawn, though nonlinear, to classify these quite clearly. Artificial neural network models work very well on such data

The other major strength of the ANN model is its capacity to handle large amount of data. Traditionally, it has been thought that a usable prediction instrument has to be based on relevant minimal information. This in part accrues from the fact that humans, in general, have a limited ability to incorporate multiple types of information in the decision-making process. Our short-term memory can simultaneously retain—and therefore optimally utilize—only 4–7 data constructs [40]; attempts to use larger amounts of information at one time can lead to ineffective decision making. This may be where computer-based clinical decision support systems supported by electronic medical records are able to impact on patient management by assimilating large amount of input information typically available in a patient from history, physical examination, and laboratory variables, providing a consistent, validated approach to decision making. Thus, we feel ANN-based models, which can incorporate and analyze any number of input information, are likely to be more portable, flexible, and potentially more clinically useful compared to MELD or the CTP score, which takes into account only a few selected variables based on an analysis of the original cohort, and ignores the rest of the very pertinent and routinely available clinical information.

What is an artificial neural network?

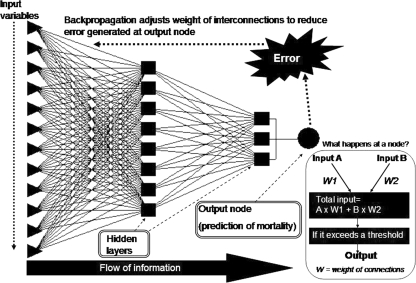

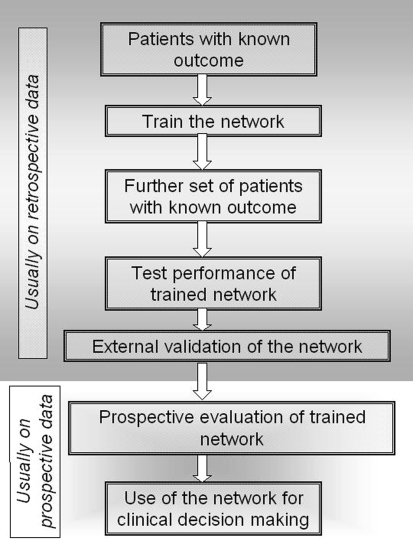

Artificial neural networks are computational paradigms based on mathematical models that unlike traditional computing have a structure and operation that resembles that of the mammal brain. They are also called connectionist systems, parallel distributed systems, or adaptive systems, because they are composed of a series of interconnected processing elements that operate in parallel. Neural networks lack centralized control in the classical sense, since all the interconnected processing elements change or “adapt” simultaneously with the flow of information and adaptive rules [41–43]. Several reviews on ANN have been published recently [41, 43–50]. Although there are several types of neural networks, multilayer perceptron is the most commonly used network. Figure 2 shows a schematic diagram of a multilayer perceptron ANN model that can predict mortality in patients with cirrhosis of liver [39]. The network consists of input nodes (triangles) representing different clinical and laboratory variables of patients with cirrhosis of liver, which are entered to predict mortality, variable number of layers of hidden nodes (rectangular) and one or more output nodes (circular) that gives the predicted output, which in the current network is a dichotomous (yes/no) variable representing mortality. The inset within the box shows in a simplified manner how the network works. Initially the network is trained with the data of a proportion of patients whose outcome is known to the network. Such a model is called a feed-forward network. Each time the network makes a prediction with errors, back-propagation adjusts the weight of the interconnections to give an output that is closest to the actual outcome (Fig. 2). Once the network is reasonably trained, its efficacy is validated with the outcome of the other patients, which is not known to the network. It is important to validate the predictive accuracy of such a model in an external validation cohort. Subsequently, it can be subjected to prospective validation and clinical use (Fig. 3). Each time a patient’s data are entered for validation, the network continues to learn through examples [51].

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of a feed-forward artificial neural network model (multilayer perceptron network). Inset shows what happens in a node in a simplified manner. Each of the very large number of processing units fires an output value that is equal to the weighted sum of the outputs of the units in the preceding layer minus the threshold value of that node. This is known as activation function or transfer function, which can be negative or positive

Fig. 3.

Flow chart showing steps of development, validation, and finally clinical use of an ANN-based predictive model

Review of studies on ANN for prediction of the outcome of chronic liver disease

Artificial neural network have been used in medicine for varied purposes, including prediction of mortality of patients with cirrhosis of the liver [35, 47, 51, 52]. We compared an ANN model with Child–Pugh’s scoring and a conventional logistic regression model based on the same variables that were used for the ANN model to predict 1-year liver disease-related mortality in 154 patients with cirrhosis of the liver [35]. Of these 154 patients, 62 were from a different center than the one whose data have been used to train the network. This is called external validation of the performance of the network. Of the remaining 92 patients, 46 were randomly selected for training and 46 for internal validation. The patients for external validation were somewhat different than the patients used for training and internal validation as they were younger (mean age, 41 vs. 45 year), infrequently of alcoholic etiology (5% vs. 49%), had less severe liver disease (mean Child–Pugh score 6.6 vs. 10.8) and had lower 1-year mortality (13% vs. 46%). In the internal validation sample, ANN’s accuracy was 91%, sensitivity 90%, and specificity 92% in the prediction of 1-year mortality. Despite difference between the training and external validation sample, the ANN performed fairly well in the external validation sample (accuracy 90%), suggesting that the network was reasonably robust to be of clinical use in different patient populations. Performance of the logistic regression model (accuracy 74%) and Child–Pugh scoring (accuracy 55%) was significantly worse than the ANN model. Superior performance of the ANN compared with Child–Pugh’s scoring system is quite expected, as the former uses larger number of input variables to make the predictions. Moreover, the ANN is a dynamic model, and with each error in predicting the outcome of each new patient the network back-propagates to adjust the weight of the connections, thereby altering the transfer function (output, Fig. 2) in each hidden node, improving its predictive accuracy, similar to what happens in the human brain [39].

In another study [53], an ANN model was compared with MELD scoring to predict 3-month mortality in 388 patients with cirrhosis of the liver who were listed for liver transplantation at two centers. Of these 388 patients, 137 were from a different center than the one whose data have been used to train the network. A total of 138 patients were used to train the network, 63 for internal validation, and 137 for external validation. The ANN model was found to perform significantly better than the MELD both in the internal validation group (area under the receiver operator characteristic [ROC] curve = 0.95 vs. 0.85, P ≤ 0.05) and in the external validation group (area under the ROC curve = 0.96 vs. 0.86, P < 0.05).

In another study on 144 alcoholic patients with severe liver disease, the performance of an ANN model using clinical and laboratory data was evaluated and compared with Maddrey discriminant function and logistic regression models in predicting the mortality of alcoholic patients with severe liver disease [54]. Performance of ANN was significantly better than that of Maddrey score (ROC areas 0.81 vs. 0.73, 8%, P = 0.04). ROC area for the ANN model, however, was similar to that of the logistic regression model (ROC area 0.78; P = 0.3). A limitation of this study was lack of external validation of the model.

Since only one study has compared MELD score—which is one of the most popular scoring system for the prediction of mortality from cirrhosis of the liver and, hence, need for transplantation—with ANN-based models till date and showed ANN to be superior to MELD [53], more such studies are urgently needed.

What are the advantages of ANN models in predicting mortality from cirrhosis of the liver?

Although only a few studies have been done to evaluate the efficacy of ANN in predicting mortality from cirrhosis of the liver, all these studies proved ANN models to be far more superior as compared to other scoring systems in predictive performance. The possible reasons for superior performance of ANN models include the following: (a) All conventional statistical models such as regression-based models presume that the data is linear, although most biological data are nonlinear [39]. Neural networks-based models are more suited for pattern recognition in multidimensional nonlinear interactions (Fig. 1). (b) The predictive instruments derived on the basis of most regression models are usually based on a small number of variables (e.g., MELD score takes into account only three variables) Arguably, a large number of other variables that may not reach statistical significance to be incorporated in a regression model may indeed influence outcome and cumulatively add to the predictive ability of a prognostic model [35]; for example, a patient with cirrhosis of the liver with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and septicemia is more likely to die if he has renal failure and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus than if he does not have the latter two associated diseases. (c) ANN models are dynamic and continue to learn each time a new patient’s data are entered [39]; in contrast, a logistic regression model is not dynamic in that the derivation cohort for most models would not change over time. Thus, there is no scope to incorporate new information without building and revalidating a new regression model. A logistic regression-based predictive instrument constructed and validated decades earlier may not have the same predictive ability today, as management and mortality of chronic liver disease might have changed over the years owing to continual improvement in treatment. In contrast, such problems are unlikely with ANN-based models because of its continued learning capability analogous to the brain.

What are the problems of the ANN model in predicting mortality from cirrhosis of the liver?

Despite demonstrated superior performance of the ANN in this setting and also in many other fields of medicine, the clinical application of neural network technology remains very limited. What could be the reasons for this? (a) ANN represents application of advanced computational and mathematical techniques. Although many commercially available ANN software are built in a plug-and-play manner, to apply this technology, one needs to have a basic understanding of the principles of ANN and pattern recognition, which may be intimidating to many healthcare providers [55, 56]. (b) One of the limitations of ANN is that it works with a “black-box” approach, which means that part of the model and its inferences cannot often be broken down into simple pieces of clinical reasoning and this could be disconcerting to clinicians [57]. (c) The sample size required for ANN-based models is quite large and often impractical. (d) Unless these models are validated in multiple sets of external validation groups, the predictive performance of the network might be fallacious and related to “overlearning,” although the techniques used to reduce overlearning are quite effective. (e) A large number of variables need to be entered into the computers for making predictions through ANN-based models, which make clinicians averse to use this for clinical decision-making. For example, to calculate MELD score, a physician needs to enter the values of only three variables into a calculator, which would take much less time than if he has to enter the values of 20–30 variables into an ANN model in a computer. On the other hand, ANN models are microcomputer based and can quickly process a large number of variables. Given the increasing availability of electronic medical records, a large number of predetermined input variables could be automatically selected from electronic patient records, and in this age of information technology, the argument for brevity in building such predictive models is weak. Also sophisticated input variable selection methods such as genetic input selection algorithms are very effective in developing compact but accurate models. Last, one of the reasons why the ANN model has not been widely used is the well-known issue of physician nonacceptance of computer-based decision aids, and several barriers to use of computer-based decision support systems by physicians are often cited [58].

It is important to note that the sample size required to train and validate the network is quite large and is generally accepted to be ten times the number of variables. Also, more is the number of centers for external validation of the model, more is the robustness and practical utility of the network. If the network is generated from a small sample size and without much external validation, it will be prone to overlearning, which means that though such a network would perform very well for prediction on the same data set, it may not do so when it is used to predict the outcome of patients during prospective evaluation in the same center or on patients from other centers.

Future directions

There is obviously a need for more studies on ANN models for controlled comparison with other scoring systems and for validation of its predictive ability in predicting short- and long-term mortality in patients with cirrhosis of the liver. Such models will also need to be validated prospectively for use in decision making regarding organ allocation in liver transplantation centers [41, 47]. Since only one study has been published till date comparing MELD score with ANN-based models for prediction of mortality from cirrhosis of the liver, such studies are urgently needed. There is substantial evidence from trials in a wide range of clinical settings that computer decision support systems are effective in improving patient care. Designing and implementing such systems is challenging because of the computing infrastructure that is required. Despite these difficulties, as computer-based records and order-entry systems become more common, it is almost certain that automated decision support systems will be used more broadly for medical decision making and an obvious application of such technology is to help improve our prognostic ability in complex diseases such as cirrhosis of the liver.

References

- 1.Perkins J. Liver transplantation worldwide. Liver Transpl 2006;12:159–62 [DOI]

- 2.Chaib E, Massad E. Liver transplantation: waiting list dynamics in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Transplant Proc 2005;37:4329–30 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Analysis of waiting times. In: Committee on organ transplantation: assessing current policies and the potential impact of the DHHS final rule. Washington: National Academy Press. 1999. p. 57–78

- 4.Hunt D, Haynes R, Hanna S, Smith K. Effects of computer-based decision support systems on physician performance and patient outcomes. JAMA 1998;280:1339–46 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Blumenthal D. The future of quality measurement and management in a transforming health care system. JAMA 1997;278:1622–5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Infante-Rivard C, Esnaola S, Villeneuve JP. Clinical and statistical validity of conventional prognostic factors in predicting short-term survival among cirrhotics. Hepatology 1987;7:660–4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Forman L, Lucey M. Predicting the prognosis of chronic liver disease: an evolution from Child to MELD. Hepatology 2001;33:473–5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ho YP, Chen YC, Yang C, Lien JM, Chu YY, Fang JT, et al. Outcome prediction for critically ill cirrhotic patients: a comparison of APACHE II and Child–Pugh scoring systems. J Intensive Care Med 2004;19:105–10 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Nagashima I, Takada T, Okinaga K, Nagawa H A. scoring system for the assessment of the risk of mortality after partial hepatectomy in patients with chronic liver dysfunction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2005;12:44–8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Serra MA, Puchades MJ, Rodriguez F, Escudero A, del Olmo JA, Wassel AH, et al. Clinical value of increased serum creatinine concentration as predictor of short-term outcome in decompensated cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004;39:1149–53 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Yoneyama K, Taniguchi H, Kiuchi Y, Shibata M, Mitamura K. Prognostic index of liver cirrhosis with ascites with and without hepatocellular carcinoma. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004;39:1272–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Zauner CA, Apsner RC, Kranz A, Kramer L, Madl C, Schneider B, et al. Outcome prediction for patients with cirrhosis of the liver in a medical ICU: a comparison of the APACHE scores and liver-specific scoring systems. Intensive Care Med 1996;22:559–63 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Huo TI, Lin HC, Wu JC, Lee FY, Hou MC, Lee PC, et al. Proposal of a modified Child–Turcotte–Pugh scoring system and comparison with the model for end-stage liver disease for outcome prediction in patients with cirrhosis. Liver Transpl 2006;12:65–71 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Arabi Y, Ahmed QA, Haddad S, Aljumah A, Al-Shimemeri A. Outcome predictors of cirrhosis patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;16:333–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Korner T, Kropf J, Kosche B, Kristahl H, Jaspersen D, Gressner AM. Improvement of prognostic power of the Child–Pugh classification of liver cirrhosis by hyaluronan. J Hepatol 2003;39:947–53 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Merkel C, Morabito A, Sacerdoti D, Bolognesi M, Angeli P, Gatta A. Updating prognosis of cirrhosis by Cox’s regression model using Child–Pugh score and aminopyrine breath test as time-dependent covariates. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998;30:276–82 [PubMed]

- 17.Ripoll C, Banares R, Rincon D, Catalina MV, Lo Iacono O, Salcedo M, et al. Influence of hepatic venous pressure gradient on the prediction of survival of patients with cirrhosis in the MELD Era. Hepatology 2005;42:793–801 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Tsuji Y, Koga S, Ibayashi H, Nose Y, Akazawa K. Prediction of the prognosis of liver cirrhosis in Japanese using Cox’s proportional hazard model. Gastroenterol Jpn 1987;22:599–606 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Sumskiene J, Kupcinskas L, Pundzius J, Sumskas L. Prognostic factors for short and long-term survival in patients selected for liver transplantation. Medicina (Kaunas) 2005;41:39–46 [PubMed]

- 20.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg 1973;60:646–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Christensen E, Krintel JJ, Hansen SM, Johansen JK, Juhl E. Prognosis after the first episode of gastrointestinal bleeding or coma in cirrhosis. Survival and prognostic factors. Scand J Gastroenterol 1989;24:999–1006 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Abad-Lacruz A, Cabre E, Gonzalez-Huix F, Fernandez-Banares F, Esteve M, Planas R, et al. Routine tests of renal function, alcoholism, and nutrition improve the prognostic accuracy of Child–Pugh score in nonbleeding advanced cirrhotics. Am J Gastroenterol 1993;88:382–7 [PubMed]

- 23.Gatta A, Merkel C, Amodio P, Bellon S, Bellumat A, Bolognesi M, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic index predicting death after upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis: a multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:1528–36 [PubMed]

- 24.Adler M, Verset D, Bouhdid H, Bourgeois N, Gulbis B, Le Moine O, et al. Prognostic evaluation of patients with parenchymal cirrhosis. Proposal of a new simple score. J Hepatol 1997;26:642–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Bustamante J, Rimola A, Ventura PJ, Navasa M, Cirera I, Reggiardo V, et al. Prognostic significance of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1999;30:890–5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Chalasani N, Clark WS, Martin LG, Kamean J, Khan MA, Patel NH, et al. Determinants of mortality in patients with advanced cirrhosis after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting. Gastroenterology 2000;118:138–44 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Kamath PS, Kim WR. The Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD). Hepatology 2007;45:797–805 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Salerno F, Merli M, Cazzaniga M, Valeriano V, Rossi P, Lovaria A, et al. MELD score is better than Child–Pugh score in predicting 3-month survival of patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. J Hepatol 2002;36:494–500 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Buenadicha AL, Martin LG, Martin EE, Pajares AD, Perez AM, Seral CC, et al. Assessment of short-term survival after liver transplant by the Model for End-stage Liver Disease. Transplant Proc 2005;37:3881–3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Oton-Nieto E, Barcena-Marugan R, Carrera-Alonso E, Blesa-Radigales C, Garcia-Gonzalez M, Nuno J, et al. Variability of MELD score during the year before liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 2005;37:3887–8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 2001;33:464–70 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Schrander-van der Meer AM, Vogten AJ. Estimation of survival probability in cirrhotics. Evaluation of a computer model applicable for decision-making. Neth J Med 1992;40:183–9 [PubMed]

- 33.van Dam GM, Verbaan BW, Therneau TM, Dickson ER, Malinchoc M, Murtaugh PA, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis: Dutch application of the Mayo Model before and after orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatogastroenterology 1997;44:732–43 [PubMed]

- 34.Sheth M, Riggs M, Patel T. Utility of the Mayo End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score in assessing prognosis of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. BMC Gastroenterol 2002;2:2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Banerjee R, Das A, Ghoshal UC, Sinha M. Predicting mortality in patients with cirrhosis of liver with application of neural network technology. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;18:1054–60 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Child III CG, Turcotte JG. Surgery and portal hypertension. In: Child III CG, (editor). The liver and portal hypertension. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1964. p. 50

- 37.Freeman RB, Wiesner RH, Edwards E, Harper A, Merion R, Wolfe R. Results of the first year of the new liver allocation plan. Liver Transpl 2004;10:7–15 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Cholongitas E, Marelli L, Shusang V, Senzolo M, Rolles K, Patch D, et al. A systematic review of the performance of the Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) in the setting of liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2006;12:1049–61 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Cross S, Harrison R, Kennedy R. Introduction to neural networks. Lancet 1995;346:1075–79 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Miller GA. The magical number seven plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychol Rev 1956;63:81–97 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Forsstrom JJ, Dalton KJ. Artificial neural networks for decision support in clinical medicine. Ann Med 1995;27:509–17 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Dayhoff JE, DeLeo JM. Artificial neural networks: opening the black box. Cancer 2001;91:1615–35 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Rodvold DM, McLeod DG, Brandt JM, Snow PB, Murphy GP. Introduction to artificial neural networks for physicians: taking the lid off the black box. Prostate 2001;46:39–44 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Boutsinas B, Vrahatis M. Artificial nonmonotonic neural networks. Artificial Intelligence 2001;132:1–38 [DOI]

- 45.Lisboa P. A review of evidence of health benefit from artificial neural networks in medical intervention. Neurol Network 2002;15:11–39 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Ramesh AN, Kambhampati C, Monson JR, Drew PJ. Artificial intelligence in medicine. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2004;86:334–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Sharpe PK, Caleb P. Artificial neural networks within medical decision support systems. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl 1994;219:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Tafeit E, Reibnegger G. Artificial neural networks in laboratory medicine and medical outcome prediction. Clin Chem Lab Med 1999;37:845–53 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Winkler DA. Neural networks as robust tools in drug lead discovery and development. Mol Biotechnol 2004;27:139–68 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Dytch HE, Wied GL. Artificial neural networks and their use in quantitative pathology. Anal Quant Cytol Histol 1990;12:379–93 [PubMed]

- 51.Khan ZH, Mohapatra SK, Khodiar PK, Ragu Kumar SN. Artificial neural network and medicine. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 1998;42:321–42 [PubMed]

- 52.Itchhaporia D, Snow PB, Almassy RJ, Oetgen WJ. Artificial neural networks: current status in cardiovascular medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28:515–21 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Cucchetti A, Vivarelli M, Heaton ND, Phillips S, Piscaglia F, Bolondi L, et al. Artificial neural network is superior to MELD in predicting mortality of patients with end-stage liver disease. Gut 2007;56:253–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Lapuerta P, Rajan S, Bonacini M. Neural networks as predictors of outcomes in alcoholic patients with severe liver disease. Hepatology 1997;25:302–6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Plumb AP, Rowe RC, York P, Brown M. Optimisation of the predictive ability of artificial neural network (ANN) models: a comparison of three ANN programs and four classes of training algorithm. Eur J Pharm Sci 2005;25:395–405 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Chen Y, Jiao T, McCall TW, Baichwal AR, Meyer MC. Comparison of four artificial neural network software programs used to predict the in vitro dissolution of controlled-release tablets. Pharm Dev Technol 2002;7:373–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Wyatt J. Nervous about artificial neural networks?. Lancet 1995;346:1175–7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Garibaldi R. Computers and the quality of care—A clinician’s perspective. New Engl J Med 1998;338:259–60 [DOI] [PubMed]