Abstract

Purpose

A phase II study was conducted to determine the response rate of ixabepilone (BMS-247550, National Cancer Institute (NCI)–supplied agent investigational new drug No. 59,699) in patients with persistent or recurrent endometrial cancer who have progressed despite standard therapy.

Patients and Methods

Eligible patients had recurrent or persistent endometrial cancer and measurable disease. One prior chemotherapeutic regimen, which could have included either paclitaxel or docetaxel, was allowed. Patients received ixabepilone 40 mg/m2 as a 3-hour infusion on day 1 of a 21-day cycle. Treatment was continued until disease progression or until unacceptable toxicity occurred.

Results

Fifty-two patients were entered on the study, and 50 of these were eligible. The median age was 64 years (range, 40 to 83 years). Prior treatment included radiation in 21 patients (42%) and hormonal therapy in eight patients (16%). All patients had prior chemotherapy, and 47 (94%) received prior paclitaxel therapy. The overall response rate was 12%; one patient achieved a complete remission (2%), and five achieved partial remission (10%). Stable disease for at least 8 weeks was noted in 30 patients (60%). The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 2.9 months, and the 6-month PFS was 20%. Major grade 3 toxicities were neutropenia (52%), leukopenia (48%), gastrointestinal (24%), neurologic (18%), constitutional (20%), infection (16%), and anemia (14%).

Conclusion

In a cohort of women with advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer who were previously treated with paclitaxel, ixabepilone showed modest activity of limited duration as a second-line agent.

INTRODUCTION

Endometrial cancer is the most common cancer of the female reproductive system and is the fourth most common cancer in women.1 In 2007, endometrial cancer accounted for nearly 40,000 cases in the United States and was responsible for more than 7,000 deaths.1 Although many women present at an early stage and can expect treatment with curative intent through surgery with or without adjuvant radiation, some will experience relapse with locally advanced or metastatic disease.

Currently, the standard of care for women who present with locally advanced or who experience relapse with metastatic disease is to proceed with an anthracycline, taxane, and platinum combination. This followed the publication of Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) trial 177, which established the effectiveness of first-line paclitaxel, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (TAP) compared with doxorubicin and cisplatin (AP) in this population. In this trial, TAP increased the response rate compared with AP (57% v 34%; P < .01) and was also associated with improvements in progression-free survival (PFS; median, 8.3 v 5.3 months; P < .1) and overall survival (OS; 15.3 v 12.3 months; P < .05).2 Subsequent to this, the results of GOG-122 were released, which supported the use of systemic chemotherapy (AP) compared with whole abdominal radiation (WAR) after surgery in patients who had stages III to IV endometrial cancer with no more than 2 cm of postoperative residual disease identified. In that trial, adjuvant AP was associated with a 29% improvement in the risk of disease progression (hazard ratio [HR], 0.71; 95% CI, 0.55 to 0.91) and a 32% improvement in the risk of dying (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.89).3 These results heralded a change in treatment patterns for women with advanced disease and ushered in the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in this malignancy.

With the more frequent use of adjuvant or first-line chemotherapy, there is now a limited choice of agents for women who subsequently experience relapse, which points to the need for additional research in other treatments for women with endometrial cancer.

The epothilones are a novel class of nontaxane microtubule-stabilizing agents with a mode of action similar to paclitaxel. Ixabepilone is a semisynthetic analog of the natural product epothilone B. It has shown preclinical activity against paclitaxel-resistant and paclitaxel-insensitive breast, lung, and colon cell lines and recently has received US Food and Drug Administration approval as a treatment option in metastatic breast cancer that is refractory to capecitabine, anthracyclines, and taxanes.4,5

Given the activity of single-agent ixabepilone in cell lines and in breast cancer, this phase II study was designed to define the activity and the toxicity profile of ixabepilone in women with advanced endometrial cancer.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Selection

Eligible patients met the following criteria: histologic confirmation of the primary tumor by central review of the GOG pathology committee; GOG performance status of 0 to 2; recovery from the effects of recent surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy; one prior chemotherapeutic regimen for endometrial adenocarcinoma, which may have included high-dose therapy, consolidation, or extended treatment after surgical or nonsurgical assessment; freedom of active infection that required antibiotics; discontinuation of hormonal therapy directed at the malignant tumor at least 1 week before registration; discontinuation of prior therapy, including biologics and immunologic agents, at least 3 weeks before registration; adequate hematologic function, defined as absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥ 1,500/μL and platelet count ≥ 100,000/μL; adequate renal function, defined as creatinine ≤ 1.5 times the institutional upper limit of normal (ULN); adequate hepatic function, defined as bilirubin ≤ 1.5 times the ULN and as AST and alkaline phosphatase ≤ 2.5 times the ULN; neuropathy (sensory and motor) of grade 1 or less; protocol approval by each institution's institutional review board (IRB); signed, approved informed consent and authorization to permit release of personal health information by each patient; (14) negative serum pregnancy test before study entry and agreement to practice an effective form of contraception in patients of childbearing potential.

Patients were ineligible if they met any of the following criteria: prior treatment with ixabepilone; prior history of other invasive malignancies, with the exception of nonmelanoma skin cancer, if there was any evidence of other malignancy present within the last 5 years; and contraindication of the protocol therapy by prior cancer treatment.

The primary objective was to define the response rate of ixabepilone in women with recurrent, persistent, or metastatic endometrial cancer. A secondary objective was to determine the nature and degree of toxicity of ixabepilone in this cohort of patients. Patients were required to have measurable disease by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors. Patients who had received one prior systemic chemotherapy regimen were eligible, and prior treatment with paclitaxel or docetaxel was allowed.

Treatment

Each treatment cycle consisted of 21 days in which ixabepilone 40 mg/m2 was administered as an intravenous (IV) infusion. Premedication, which consisted of diphenhydramine 50 mg orally or IV and ranitidine 150 mg orally or 50 mg IV (or another equivalent histamine 2 blocker) administered 1 hour to 30 minutes before ixabepilone, was required.

Subsequent cycles were administered only when the ANC reached 1,500/μL or greater and when platelets recovered to 100,000/μL or higher. Therapy was delayed for a maximum of 2 weeks to allow recovery, and patients who failed to recover in this time frame were removed from the study. Dose reduction to 30 mg/m2 was required for the following: first occurrence of febrile neutropenia; documented, grade 4 neutropenia that persisted ≥ 7 days; or grade 4 thrombocytopenia. Dose delay for up to 2 weeks and dose reduction to 30 mg/m2 were required for: grade 2 or greater peripheral neuropathy, renal toxicity, or hepatic enzyme elevations; persistent (greater than 24 hours) grade 3 or greater nausea, emesis, diarrhea, or constipation despite optimal medical management; and other nonhematologic toxicities with an impact on organ function of grade 2 or greater.

Patients did not receive prophylactic growth factors (ie, filgrastim, sargramostatin, or pegfilgrastim) unless they experienced recurrent febrile neutropenia and/or recurrent documented grade 4 neutropenia that persisted for ≥ 7 days despite initial dose reduction. Patients were allowed to receive erythropoietin for management of anemia after documentation of hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL. Patients were not allowed to receive amifostine or other protective agents. Eligible patients received therapy until disease progression or intolerable toxicity intervened.

Evaluation Criteria

Response was evaluated for efficacy after every second cycle. Patients were evaluated for toxicity if they received any protocol therapy. Response was determined by using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.6 However, if the only target lesion was a solitary pelvic mass by physical exam, which was not radiographically measurable, then a 50% decrease in longest dimension (LD) was required to meet criteria for a partial remission, and a 50% increase in LD was required for disease progression. Symptomatic deterioration was defined as global deterioration in health status attributable to the disease that required a change in therapy without objective evidence of progression of disease. Patients defined as having no repeat tumor assessments after initiation of study therapy, for reasons unrelated to symptoms or signs of disease, were classified as nonassessable for response.

Progression was defined as any of the following criteria: at least a 20% increase in the sum of LD, in which the reference was the smallest sum LD recorded since study entry; a 50% increase in the LD of a solitary pelvic mass not assessable by radiographic methods, in which the reference was the smallest LD recorded since study entry; appearance of new lesions; death as a result of disease without prior objective documentation of progression; (5) global deterioration in health status attributable to the disease that required a change in therapy without objective evidence of progression; unequivocal progression of existing nontarget lesions, other than pleural effusions, without cytologic proof of neoplastic origin (in the opinion of the treating physician).

OS is defined as the observed length of life from entry into the study to death or to the date of last contact. PFS is defined from entry into the study to the date of progression or last contact.

Statistics

This study employed an optimal, but flexible, two-stage design that used an early stopping rule intended to limit patient accrual to inactive treatments.7 During the first stage, the targeted accrual was 19 to 26 patients because of administrative coordination. If more than two of the 25, or three of the 26, patients responded, and if medical judgment was indicated, accrual to the second stage was initiated. Otherwise, the study would be stopped, and the treatment regimen would be classified as uninteresting. If opened to the second stage, the overall study accrual would be to 48 eligible and assessable patients, but it was permitted to range from 44 to 51 patients for administrative reasons. If more than six of the 44 to 45 or seven of the 46 to 51 patients responded, then the regimen would be considered worthy of additional investigation.

If the true probability of responding was only 10%, the study design provided a 90% chance of correctly classifying the treatment as inactive. Conversely, if the true response rate was 25%, then the average probability of correctly classifying the treatment as active was 90%.

RESULTS

Between May 2005 and January 2008, member institutions enrolled 52 patients onto this trial. Two patients were deemed ineligible because of second primary cancers, and the remaining 50 patients were assessable for toxicity and response. Patient demographics are listed in Table 1. The median age was 64 years (range, 40 to 83 years), and the majority of patients had a performance status of 0 to 1. Forty-nine patients (98%) had received prior chemotherapy, and 47 patients (94%) had received prior treatment with paclitaxel.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Variable | Patients (N = 50) |

|

|---|---|---|

| No. | % | |

| Total No. of patients entered | 52 | |

| Total No. of patients eligible | 50 | |

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 64 | |

| Range | 40-83 | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 40 | 80 |

| Black | 5 | 10 |

| American Indian | 3 | 6 |

| Asian | 1 | 2 |

| Unknown | 1 | 2 |

| EGOG PS | ||

| 0 | 27 | 54 |

| 1 | 22 | 44 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Histology | ||

| Endometrioid | 23 | 46 |

| Serous | 20 | 40 |

| Mixed epithelial | 5 | 10 |

| Clear cell | 1 | 2 |

| Adenocarcinoma NOS | 1 | 2 |

| Tumor grade | ||

| 1 | 3 | 6 |

| 2 | 15 | 30 |

| 3 | 32 | 64 |

| Prior radiotherapy | 21 | 42 |

| Prior hormonal therapy | 8 | 16 |

| Prior chemotherapy | ||

| Paclitaxel | 47 | 94 |

| Platinum | 50 | 100 |

| Doxorubicin | 10 | 20 |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status; NOS, not otherwise specified.

A total of 224 courses were administered, and a median of four courses were given. Twelve patients (24%) received more than six courses. Seven patients had dose reductions for febrile neutropenia (n = 3), grade 2 neuropathy (n = 2), gastrointestinal toxicity despite optimal management (n = 1) and grade 3 fatigue (n = 1). Thirty patients (60%) experienced alopecia, which was complete (grade 2) in 23 patients (46%). A prior history of radiotherapy did not predict the incidence of grades 3 to 4 myelotoxicity or neurotoxicity.

Adverse events associated with protocol treatment are listed in Table 2. The major toxicities (grades 3 to 4) were neutropenia (52%), leukopenia (48%), gastrointestinal (24%), constitutional (20%), neurologic (18%), infection (16%), and anemia (14%). There was one death on study that occurred in an elderly woman with a history of Parkinson's disease. After her fifth treatment, she was hospitalized for increased confusion and the rapid onset of shortness of breath. Serial chest x-rays demonstrated evolving pulmonary infiltrates with a differential of congestive heart failure versus acute interstitial pneumonia and concern of acute respiratory distress syndrome. She subsequently required intensive management, but she ultimately died of progressive hypoxemia. A biopsy of the lung showed nonspecific infiltrative changes. The Data Safety and Monitoring Board of the GOG ultimately determined this was related to protocol treatment.

Table 2.

Adverse Events

| Adverse Event | NCI CTC Grade |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Leukopenia | 9 | 18 | 14 | 28 | 17 | 34 | 7 | 14 | — | — |

| Neutropenia | 5 | 10 | 7 | 14 | 14 | 28 | 12 | 24 | — | — |

| Anemia | 12 | 24 | 29 | 58 | 6 | 12 | 1 | 2 | — | — |

| Thrombocytopenia | 13 | 26 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | — | — |

| Allergy/immunology | 4 | 8 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Auditory/ear | — | — | 2 | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Cardiac | 1 | 2 | — | — | 2 | 4 | — | — | — | — |

| Coagulation | — | — | — | — | 1 | 2 | — | — | — | — |

| Constitutional | 15 | 30 | 14 | 28 | 9 | 18 | 1 | 2 | — | — |

| Dermatologic | 7 | 14 | 21 | 42 | 2 | 4 | — | — | — | — |

| Gastrointestinal | 11 | 22 | 15 | 30 | 12 | 24 | — | — | — | — |

| Genitourinary | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Hemorrhage | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | — | — | — | — |

| Infection | — | — | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | — | — | — | — |

| Lymphatics | 8 | 16 | 2 | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Metabolic | 9 | 18 | 8 | 16 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | — | — |

| Musculoskeletal | 3 | 6 | 4 | 8 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Neurosensory | 19 | 38 | 7 | 14 | 4 | 8 | — | — | — | — |

| Other neurologic | 4 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 | — | — |

| Ocular/visual | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Pain | 9 | 18 | 8 | 16 | 3 | 6 | — | — | — | — |

| Pulmonary | 10 | 20 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 4 | — | — | 1 | 2 |

| Alopecia | 7 | 14 | 23 | 46 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Vascular | — | — | 1 | 2 | — | — | 1 | 2 | — | — |

Abbreviation: NCI CTC, National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria.

The overall response rate was 12% (Table 3). One patient (2%) had a complete response, which has lasted 4.9 or more months. The response durations of the five (10%) partial responses were 4.2, 5.3, 6.3, 7.2, and 19.8 months. Five of the six responses were seen in women with endometrioid carcinomas; only one response was seen with the serous tumor. The complete response was noted in a 72-year-old patient originally diagnosed with a recurrent, stage IC, grade 2 tumor who underwent primary hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophrectomy, and pelvic and para-aortic node dissection but who relapsed 6 months after diagnosis. She received carboplatin and paclitaxel at relapse and progressed on treatment. She experienced a complete response after four cycles of ixabepilone. A prolonged partial response was seen in a 60-year-old woman with a stage III, grade 3, endometrioid adenocarcinoma who also had undergone primary surgery that consisted of bilateral salpingo-oophrectomy and pelvic and para-aortic node dissection followed by adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel; she experienced relapse 10 months after the end of adjuvant treatment. On ixabepilone, she experienced a response after two cycles.

Table 3.

Response Rates

| Clinical Response Category | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Complete response | 1 | 2 |

| Partial response | 5 | 10 |

| Stable disease | 30 | 60 |

| Progressive disease | 13 | 26 |

| Nonassessable | 1 | 2 |

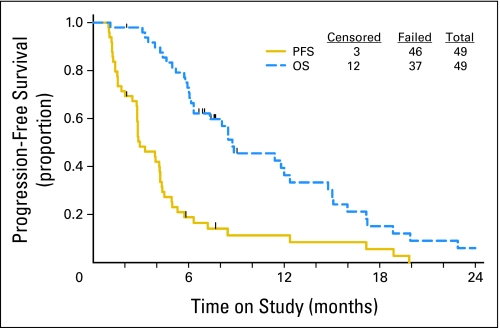

Thirty patients (60%) had stable disease. For all patients, the median PFS was 2.9 months (Fig 1), and the proportion that was progression free at 6 months was 20%. Median OS was at least 8.7 months.

Fig 1.

Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).

DISCUSSION

Recurrent and advanced endometrial cancer remain a treatment dilemma. Active agents in endometrial cancer are being utilized as adjuvant treatment, given the outcome of several randomized trials that showed survival advantages when platinum-based combinations were used and compared with radiation therapy. In GOG-122, patients with stages III to IV endometrial cancer who underwent tumor resection to less than 2 cm of postoperative residual disease were randomly assigned to WAR or to the combination of doxorubicin and cisplatin (AP).3 At a median follow-up of 60 months, AP was associated with a 21% improvement in PFS (HR, 0.79) and a 32% improvement in OS (HR, 0.68) compared with WAR. Subsequently, the GOG performed a first-line chemotherapy trial that compared AP with or without paclitaxel, and it showed that the addition of paclitaxel significantly improved both PFS (8.3 v 5.3 months, respectively; P < .01) and OS (15.3 v 12.3 months, respectively; P = .037).2 As a result, women with advanced uterine cancer are more often undergoing chemotherapy as an adjuvant therapy.

When women experience relapse after first-line treatment, options are relatively limited. Endocrine therapy may be of some use, but the activity of agents such as megestrol acetate and tamoxifen is limited to low-grade cancers.7 Active cytotoxic agents beyond those used in first-line regimens are listed in Table 4. However, these results reflect patients who often were treated with anthracyclines but who were taxane naïve and, for earlier studies, even platinum naïve. Therefore, the applicability of these results to today's population of women who experience relapse is unclear.

Table 4.

Summary of Active Agents as Second-Line Therapy in Endometrial Adenocarcinoma

| Agent | No. of Patients | Schedule | Overall Response Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cisplatin9 | 25 | 50 mg/m2 every 3 weeks | 4 |

| Docetaxel10 | 27 | 36 mg/m2 weekly | 7.7 |

| Paclitaxel11 | 44 | 110-200 mg/m2 over 3 hours every 3 weeks | 27.3 |

| Ifosfamide12 | 52 | 1.2 g/m2 for 5 days every 4 weeks | 15 |

| Oxaliplatin13 | 54 | 130 mg/m2 every 3 weeks | 13.5 |

| Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin14 | 42 | 50 mg/m2 every 4 weeks | 9.5 |

| Ixabepilone | 50 | 40 mg/m2 every 3 weeks | 12 |

Given the lack of available options, the results of this study are encouraging. For a population in which the majority of patients had previously received paclitaxel, a response rate of 12% was seen, which included one complete remission in a patient who progressed during carboplatin and paclitaxel as first-line treatment for metastatic disease. An additional 60% had stable disease, and PFS at 6 months was 20%, which suggests a potential clinical benefit. Interestingly, this level of activity is similar to the response rate seen in a trial of ixabepilone for taxane-resistant metastatic breast cancer, in which taxane resistance was defined as progression during or within 4 months of last taxane.5 Of note, activity seen on that study were confined to partial responses.

The toxicity of this agent was predominantly myelosuppressive. It should be noted, however, that 18% experienced grades 3 to 4 neurologic toxicity, and another 20% had constitutional symptoms. Given this data, the benefits of treatment in this advanced population must be weighed against the risks of such toxicity.

In conclusion, ixabepilone has modest activity of limited duration as a second-line treatment in endometrial adenocarcinoma in this population who largely received prior taxane therapy. The activity of ixabepilone did not meet the established bar described in the methods section to move drugs forward in the GOG in this population. However, it is worth noting that cisplatin, which forms the backbone of the adjuvant and first-line treatment of advanced or metastatic endometrial cancer, had a 4% response rate when tested in the second-line setting.9 In addition, docetaxel was associated with a 7.7% response rate, and the GOG phase II trial of this agent was halted after the first stage of accrual.10 Therefore, second-line treatment options for women with endometrial cancer remain limited, and ixabepilone's modest activity may warrant additional exploration in this setting. As part of the exploration, an understanding of the mechanisms underlying the response to ixabepilone in patients previously treated with taxanes is critical. One potential correlate for response may be class III β-tubulin (β-III tubulin). Although normally present in abundance in both the central and peripheral nervous systems, altered expression of β-III tubulin has been noted in the context of malignancy.15 Although data on endometrial cancer is lacking, expression of high levels has predicted reduced responsiveness of taxanes, whereas preclinical data in breast cancer cell lines suggest that response to ixabepilone is preserved.16,17 Because of this difference, future studies of epothilones should include an assessment of B-III tubulin levels as a correlative end point.

Acknowledgment

We thank AnnMarie Bradley, RN, who was instrumental to the study and who assisted greatly in facilitating patient-related questions as they related to those on protocol.

Appendix

The following Gynecologic Oncology Group member institutions participated in this study:

University of Alabama at Birmingham, Abington Memorial Hospital, Rush-Presbyterian-St Luke's Medical Center, State University of New York Downstate Medical Center, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Cooper Hospital/University Medical Center, Columbus Cancer Council, University of Oklahoma, Case Western Reserve University, Gynecologic Oncology Network, Women and Infants Hospital, and Community Clinical Oncology Program.

Footnotes

Supported by Grants No. CA 27469 (to the Gynecologic Oncology Group Administrative Office) and CA 37517 (to the Gynecologic Oncology Group Statistical and Data Center) from the National Cancer Institute.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Don S. Dizon, BMS (C); D. Scott McMeekin, BMS (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Don S. Dizon

Provision of study materials or patients: Don S. Dizon, D. Scott McMeekin, Sudarshan K. Sharma, Paul DiSilvestro, Ronald D. Alvarez

Collection and assembly of data: Don S. Dizon

Data analysis and interpretation: Don S. Dizon, John A. Blessing

Manuscript writing: Don S. Dizon, John A. Blessing, D. Scott McMeekin, Ronald D. Alvarez

Final approval of manuscript: Don S. Dizon, John A. Blessing, D. Scott McMeekin, Sudarshan K. Sharma, Paul DiSilvestro, Ronald D. Alvarez

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2007. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming GF, Brunetto VL, Cella D, et al. Phase III trial of doxorubicin plus cisplatin with or without paclitaxel plus filgrastim in advanced endometrial carcinoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2159–2166. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randall ME, Filiaci VL, Muss H, et al. Randomized phase III trial of whole-abdominal irradiation versus doxorubicin and cisplatin chemotherapy in advanced endometrial carcinoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:36–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.7617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee FY, Smykla R, Johnston K, et al. Preclinical efficacy spectrum and pharmacokinetics of ixabepilone. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63:201–212. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0727-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pivot X, Villanueva C, Chaigneau L, et al. Ixabepilone, a novel epothilone analog in the treatment of breast cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:593–599. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.4.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen TT, Ng TH. Optimal flexible designs in phase II clinical trials. Stat Med. 1998;17:2301–2312. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981030)17:20<2301::aid-sim927>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh M, Zaino RJ, Filiaci VJ, et al. Relationship of estrogen and progesterone receptors to clinical outcome in metastatic endometrial carcinoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thigpen JT, Blessing JA, Lagasse LD, et al. Phase II trial of cisplatin as second-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Am J Clin Oncol. 1984;7:253–256. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198406000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia AA, Blessing JA, Nolte S, et al. A phase II evaluation of weekly docetaxel in the treatment of recurrent or persistent endometrial carcinoma: A study by the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:22–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lincoln S, Blessing JA, Lee RB, et al. Activity of paclitaxel as second-line chemotherapy in endometrial carcinoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;88:277–281. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(02)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutton GP, Blessing JA, Homesley HD, et al. Phase II study of ifosfamide and mesna in refractory adenocarcinoma of the endometrium: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 1994;73:1453–1455. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940301)73:5<1453::aid-cncr2820730521>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fracasso PM, Blessing JA, Molpus KL, et al. Phase II study of oxaliplatin as second-line chemotherapy in endometrial carcinoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:523–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muggia FM, Blessing JA, Sorosky J, et al. Phase II trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in previously treated metastatic endometrial cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2360–2364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katsetos CD, Herman MM, Mork SJ. Class III B-tubulin in human development and cancer. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2003;55:77–96. doi: 10.1002/cm.10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vahdat L. Ixabepilone: A novel antineoplastic agent with low susceptibility to multiple tumor mechanisms. Oncologist. 2008;13:214–221. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2007-0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fomier MN. Ixabepilone, first in a new class of antineoplastic agents: The natural epothilones and their analogues. Clin Breast Cancer. 2007;7:757–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]