Abstract

Purpose

This study assessed the short-term and long-term efficacy of a presurgical stress management intervention at reducing mood disturbance and improving quality of life (QOL) in men undergoing radical prostatectomy (RP) for prostate cancer.

Patients and Methods

One hundred fifty-nine men were randomly assigned to a two-session (plus two boosters) presurgical stress management intervention (SM), a two-session (plus two boosters) supportive attention group (SA), or a standard care group (SC). Assessments occurred 1 month before surgery; 1 week before surgery; the morning of surgery; 6 weeks after surgery, and 6 and 12 months after surgery.

Results

Results indicated significant group differences in mood disturbance before surgery (P = .02), such that men in the SM group had significantly less mood disturbance than men in the SC group (P = .006), with no significant differences between the SM and SA or SA and SC groups. In the year after surgery, there were significant group differences on Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form survey (SF-36) physical component summary (PCS) scores (P = .004); men in the SM group had significantly higher PCS scores than men in the SC group (P = .0009), and there were no significant differences between the SM and SA or SA and SC groups. There were no group effects on prostate-specific QOL or SF-36 mental health scores.

Conclusion

These findings demonstrate the efficacy of a brief presurgical stress management intervention in improving some short-term and long-term outcomes. If these results are replicated, it may be a useful adjunct to standard care for men with prostate cancer undergoing surgery.

INTRODUCTION

A cancer diagnosis is a particularly potent stressor.1 For men with early-stage prostate cancer, treatment often involves radical prostatectomy (RP), which frequently produces short- and sometimes long-term erectile dysfunction and incontinence that may increase patients' distress and negatively affect their quality of life (QOL).2–10

Growing evidence suggests that psychosocial interventions are valuable for patients with cancer and may enhance QOL.8,11–17 Several interventions have been developed for men with prostate cancer and have shown beneficial effects, including improved physical functioning and QOL, finding positive meaning in the illness experience, and decreased distress.8,9,12,15,18,19

Most psychosocial interventions in cancer patients have been administered after the termination of adjuvant treatment. However, the presurgery period is often a period of high stress for patients with cancer, and patients may derive significant benefit from interventions at this time. Although some research has suggested that presurgical interventions can be useful for women with breast cancer, no studies have been conducted in patients with prostate cancer awaiting surgery.20–22

Existing studies of presurgical interventions in patients without cancer support the possible benefits of delivering interventions at this time point.23–25 Additionally, when patients were provided with stress management techniques before surgery, they reported less pain and distress and improved QOL, used less analgesic medication, and had lower systolic blood pressure.26–28

The primary aim of the current study was to assess the short-term (preoperative and perioperative) effects of the intervention, and the secondary aim was to assess the long-term (6 weeks and 6 and 12 months after surgery) effects of the intervention. Specifically, we hypothesized that men in the stress management (SM) group would have less mood disturbance (primary outcome) and distress before the surgery than those in the supportive attention (SA) group and standard care (SC) control group, and the SA group would in turn have lower mood disturbance and distress than men in the SC control group. In the long-term recovery period (secondary exploratory end points), we hypothesized that men in the SM group would have better QOL outcomes in both physical and mental domains than those in the SA and SC groups, and the SA group would in turn have better QOL outcomes than men in the SC control group.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Participants

Participants were men with early-stage prostate cancer who were undergoing RP at one of three hospitals within the Texas Medical Center (Houston, TX). Eligible participants were older than 18 years, undergoing a RP, able to speak and write in English, and able to come to the medical center four times before surgery or live within 100 miles of the medical center. Exclusion criteria included having had other major surgery in the preceding year, having a major psychiatric diagnosis, or currently undergoing psychiatric care or psychological counseling.

Procedure

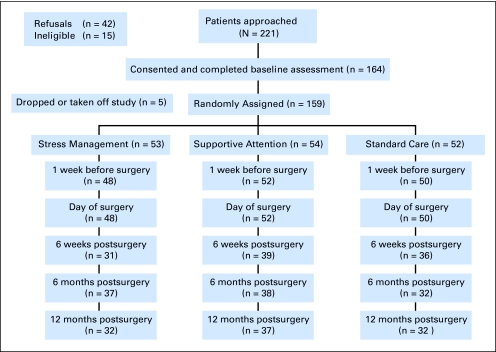

Participants attended a baseline assessment approximately 1 month before their surgery. Figure 1 outlines the study timeline. Following the baseline assessment, patients were randomly assigned to one of three groups—SM, SA, or SC—using an adaptive randomization procedure called minimization. Minimization results in better group balance than stratification.29 Characteristics used for study assignment were age (< 60 years or ≥ 60 years), partner status (living with partner or not), hospital, and type of surgical procedure (nerve sparing, non–nerve sparing, nerve graft).

Fig 1.

Recruitment and participa- tion rates.

Patients in the SM and SA groups then participated in two intervention sessions approximately 1 to 2 weeks before surgery. The same psychologists administered both the SM and SA sessions. Patients in all groups completed another assessment approximately 1 week before surgery. Another brief assessment was then completed while patients were in the holding area the morning of surgery. Patients in the SM and SA groups then had a brief booster session (approximately 5 minutes) in the holding area before going for surgery. Men in the SM and SA groups had another booster session 48 hours after surgery that lasted 10 to 15 minutes. Additional follow-up assessments were completed 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months after surgery. A dedicated research assistant, who was blinded to group assignment, collected all measures, and all procedures were the same in the three groups except for the additional psychologist contact in the SM and SA groups. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of each hospital.

Study Groups

Stress management.

The SM intervention consisted of two 60- to 90-minute individual sessions with a clinical psychologist and a Stress Management Guide that expanded on the material covered in the sessions (ie, relaxation and coping skills and information about prostate cancer and RP including management of adverse effects). The sessions were cognitive-behavioral in nature, with approximately 60% of the time focused on relaxation skills including diaphragmatic breathing and guided imagery.30 Men were given audiotapes of the techniques for practice on their own. During the second session, patients did an imaginal exposure of the day of surgery to prepare for what they might expect the morning of surgery and during hospitalization. During the rest of the sessions, men discussed their concerns or fears about the cancer and surgery and learned problem-focused coping strategies such as activity pacing, seeking out social support, and having realistic expectations about recovery. Patients also had two brief booster sessions with the clinical psychologist on the morning of surgery (before the assessment) and 48 hours after surgery to reinforce the use of relaxation strategies and the problem-focused coping strategies.

Supportive attention.

The SA group consisted of two 60- to 90-minute individual sessions with a clinical psychologist. The sessions were supportive in nature and consisted of a detailed psychosocial and medical history in a semi-structured interview format. Psychologists provided empathy and used reflective listening skills. These sessions gave the patient extra attention from the medical community and provided an encouraging environment to discuss their concerns. Patients also had brief boosters with the psychologist the morning of surgery (before the assessment) and 48 hours after surgery in which they discussed their experiences leading up to the surgery and during their hospital stay.

Standard care.

Patients in the SC group had no meetings with a clinical psychologist and received routine medical care.

Measures

A number of measures were completed in this study, including self-report measures of psychosocial adjustment and QOL; urine samples were collected to measure cortisol and catecholamine levels; and blood samples were drawn to measure immune function. In the current article, we report on the psychosocial adjustment and QOL measures.

Background and Medical Measures

Patients completed a background questionnaire that assessed age, ethnicity, employment status, marital status, and education. Medical variables were abstracted from patients' charts and included date of diagnosis, stage of disease, surgical technique, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels.

Adjustment and QOL Measures

Mood disturbance was assessed using a brief version of the Profile of Mood States (POMS).31 This 18-item measure consisted of an 11-item shortened measure that was developed for patients with cancer32 that assessed total mood disturbance, as well as the additional seven items that make up the original POMS anxiety subscale. We chose this measure because we wanted to assess mood disturbance with an emphasis on the anxiety component. The measure had good internal consistency reliability (α, 0.92 to 0.94). Higher scores indicated worse mood disturbance. It was administered at baseline, 1 week before surgery, the morning of surgery, and at the 6-week and 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Due to time limitations, the POMS was the only measure assessed the morning of surgery.

The Impact of Event Scale (IES) is a 15-item, self-report scale that assesses intrusive thoughts (intrusively experienced ideas or feelings) and avoidance behaviors (avoidance of certain feelings or situations).33 It has adequate reliability and validity.33 Patients rated the items in relation to their cancer, and the scales were combined into a total score with higher scores indicating more distress. It was administered at baseline, 1 week before surgery, and at the 6-week and 6- and 12-month follow-ups.

The Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form survey (SF-36)34,35 assessed general health-related QOL. The SF-36 assesses several domains: physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health. The RAND scoring method was used (0 [worst] to 100 [best]), and physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores were computed. It has good reliability and validity. It was completed at baseline and at the 6-week and 6- and 12-month follow-ups.

The University of California, Los Angeles, Prostate Cancer Index (PCI)36 assessed prostate cancer-specific QOL including function and bother in the urinary, bowel, and sexual domains and cancer worry. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning. The psychometric properties of this measure are good.36 It was administered at baseline and at the 6-week and 6- and 12-month follow-ups.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were computed. We examined whether there were any differences in demographic (age, ethnicity, marital status, education) and clinical (PSA at baseline, stage of disease) variables in the three groups using analysis of variance or χ2 tests and whether there were differences in the psychosocial measures at baseline. Group comparisons of the psychosocial adjustment and QOL measures were performed by regressing the follow-up assessments for each measure on time, group assignment, the group by time interaction, the respective baseline measure, and covariates (age, ethnicity, baseline PSA, and stage of disease) using general linear mixed model regression analyses. Mixed model analyses include all patients in the analyses who contribute at least one assessment in addition to baseline, which supports an intent-to-treat approach. We used PROC MIXED procedure in SAS V9.1.3 to run these analyses; the intercept was treated as random and the covariance structure was variance components. The group effect was treated as a classification variable using class statement in PROC MIXED procedure and the standard care group was the reference group. Instead of modeling time as a continuous effect, we treated time as a classified variable using class statement and the last time point in each model was the reference time point. The covariates in each model were grand-mean centered. We examined the short-term preoperative and perioperative effects of the intervention on mood disturbance (POMS) and distress (IES) separately from the long-term effects of the intervention (6 weeks and 6 and 12 months after surgery) on mood disturbance, distress, and QOL (SF-36, PCI). None of the mixed model analyses yielded significant group by time interactions, therefore we did not examine group differences at each time point but instead present the group means collapsed over time in the text and the means at each time point. The t test was used for all post hoc group comparisons. The study had 80% power to detect a 0.55 standard deviation unit change between any two groups at a single time point.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Two hundred twenty-one men were approached. Fifteen men were ineligible (five had surgery elsewhere, five did not have surgery or surgery was too soon, two had history of another cancer, one was visually impaired, and two were on antidepressants); 42 men refused (32 indicated they were too busy, one did not like to read, and nine men gave no reason). There were no differences between men who refused and those who agreed to participate on demographic characteristics (ethnicity, marital status, education, employment status, age). One hundred sixty-four men agreed to participate in the study and completed the baseline assessment (Fig 1). Five men dropped out of the study because they did not have time to participate, so 159 men were randomly assigned to one of the three groups (53, SM; 54, SA; 52, SC).

The demographic and medical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The three groups were similar on all medical characteristics (including baseline medical comorbidities) and demographic variables except ethnicity (significantly more minorities were in the SC group than in the SM and SA groups). The groups were well balanced on the factors used in the minimization procedure. There were no statistically significant differences among the groups on any of the psychosocial variables at baseline (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and Medical Characteristics by Study Group

| Characteristic | Standard Care |

Supportive Attention |

Stress Management |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Age, years | ||||||

| Mean | 60.9 | 60.7 | 59.8 | |||

| SD | 5.9 | 7.2 | 6.9 | |||

| Ethnicity* | ||||||

| White | 48 | 92 | 38 | 70 | 38 | 71 |

| African American | 3 | 6 | 7 | 13 | 11 | 21 |

| Hispanic/Latino | — | 4 | 7 | 3 | 6 | |

| Asian | — | 3 | 6 | — | ||

| Other | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/living with partner | 44 | 85 | 49 | 90 | 42 | 81 |

| Divorced/separated | 8 | 15 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 15 |

| Widowed | — | — | 1 | 2 | ||

| Never married | — | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Education | ||||||

| High school or less | 14 | 27 | 8 | 15 | 9 | 18 |

| Some college | 9 | 17 | 12 | 22 | 15 | 29 |

| College graduate | 18 | 35 | 21 | 39 | 20 | 39 |

| Graduate degree | 11 | 21 | 13 | 24 | 7 | 14 |

| Prostate-specific antigen | ||||||

| Mean | 7.0 | 7.0 | 6.5 | |||

| SD | 7.6 | 3.9 | 3.7 | |||

| Stage of disease | ||||||

| I | 7 | 13 | 7 | 13 | 6 | 12 |

| II | 39 | 75 | 42 | 79 | 35 | 69 |

| III | 6 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 19 |

| IV | — | — | — | |||

| Type of surgery | ||||||

| Non–nerve sparing | 12 | 25 | 11 | 22 | 14 | 28 |

| Nerve sparing | 34 | 69 | 33 | 66 | 32 | 64 |

| Nerve graft | 3 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 4 | 8 |

| Hospital | ||||||

| M. D. Anderson Cancer Center | 43 | 88 | 41 | 82 | 39 | 81 |

| Baylor College of Medicine | 3 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 8 |

| Veteran's Administration | 3 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 11 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Significantly different at P < .01.

Table 2.

Adjusted Means on Outcome Variables by Group at Each Assessment Time Point (Short-Term Effects)

| Outcome Variables | Group |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress Management |

Supportive Attention |

Standard Care |

||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

| Profile of Mood States–18 | ||||||

| Baseline | 10.53 | 1.05 | 9.61 | 1.50 | 10.49 | 1.40 |

| 1 week prior to surgery | 10.26 | 1.17 | 9.63 | 1.13 | 13.13 | 1.19 |

| Morning of surgery | 7.45 | 1.16 | 9.92 | 1.13 | 10.71 | 1.21 |

| Impact of Event Scale, total score | ||||||

| Baseline | 14.31 | 1.67 | 12.15 | 1.59 | 15.17 | 1.85 |

| 1 week prior to surgery | 15.51 | 1.45 | 12.41 | 1.43 | 16.00 | 1.57 |

NOTE. Follow-up means adjusted for age, ethnicity, baseline prostate-specific antigen, stage of disease, and baseline level of the outcome variable. Higher scores indicate more mood disturbance/distress.

Evaluation of Intervention

Short-term effects (1 week before surgery and morning of surgery).

Mixed model analyses indicated significant group differences for mood disturbance (least square means [SE], P value from type 3 test: SM, 8.2 [0.92]; SA, 9.8 [0.91]; SC, 11.9 [0.99]; P = .02), a significant change in mood over time with the highest levels of mood disturbance 1 week before surgery (1 week before surgery, 11.0 [0.81]; morning of surgery, 9.4 [0.81]; P = .04), and no group by time interaction (P = .22; Table 2). Post hoc analyses showed that men in the SM group had significantly less mood disturbance than did the men in the SC group (P = .006). No other group comparisons reached significance.

There were no statistically significant group differences or changes over time for IES scores (Table 2).

Long-term effects (6 weeks and 6 and 12 months postsurgery).

Mixed model analyses yielded no significant group differences or changes over time for mood disturbance or IES scores during the longer-term recovery period (all Ps > .05; data not shown).

For the PCS scores, mixed model analyses revealed significant group differences (SM, 50.9 [1.3]; SA, 48.8 [1.2]; SC, 46.1 [1.3]; P = .004), a change over time (6 week, 47.2 [1.09]; 6 month, 49.6 [1.10]; and 12 month, 49.0 [1.10]; P = .02), and no group by time interaction (P = .25; Table 3). Post hoc analyses indicated that men in the SM group had significantly higher PCS scores than did men in the SC group (P = .0009). No other group comparisons reached significance. There were no statistically significant group differences or changes over time for MCS scores (means presented in Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted Means on Outcome Variables by Group at Each Assessment Time Point (Long-Term Effects)

| Outcome Variables | Group |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress Management |

Supportive Attention |

Standard Care |

||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

| SF-36 PCS | ||||||

| Baseline | 52.79 | 0.98 | 51.32 | 1.08 | 52.29 | 0.98 |

| 6 wk postsurgery | 49.58 | 1.56 | 47.28 | 1.47 | 44.63 | 1.52 |

| 6 mo postsurgery | 51.36 | 1.49 | 48.86 | 1.44 | 48.51 | 1.68 |

| 12 mo postsurgery | 51.76 | 1.67 | 50.22 | 1.39 | 45.12 | 1.57 |

| SF-36 MCS | ||||||

| Baseline | 54.45 | 1.01 | 54.50 | 1.24 | 53.25 | 1.19 |

| Postsurgery | ||||||

| 6 weeks | 48.55 | 1.5 | 51.95 | 1.40 | 53.27 | 1.47 |

| 6 months | 52.05 | 1.43 | 53.60 | 1.38 | 53.22 | 1.60 |

| 12 months | 50.97 | 1.34 | 52.65 | 1.34 | 53.42 | 1.52 |

NOTE. Follow-up means adjusted for age, ethnicity, baseline prostate-specific antigen, stage of disease, and baseline level of the outcome variable. Higher scores indicate better quality of life.

Abbreviations: SF-36, Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form survey; PCS, physical component summary; MCS, mental component summary.

There were no significant group differences or group by time interactions for the prostate cancer–specific QOL domains (Table 4). There were significant changes over time for urinary function (P < .0001), urinary limitation (P < .0001), urinary bother (P < .0001), sexual function (P < .0001), and cancer worry (P = .004). For most scales, prostate-specific QOL declined from baseline to 6 weeks and 6 months after surgery and then improved by 12 months after surgery.

Table 4.

Adjusted Means on Outcome Variables by Group at Each Assessment Time Point (Long-Term Effects)

| Outcome Variables | Group |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress Management |

Supportive Attention |

Standard Care |

||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

| QOL–Urinary Function Scale | ||||||

| Baseline | 95.85 | 1.21 | 94.78 | 1.63 | 94.37 | 1.83 |

| Postsurgery | ||||||

| 6 weeks | 46.89 | 4.93 | 39.16 | 4.74 | 38.85 | 5.01 |

| 6 months | 68.72 | 4.73 | 59.00 | 4.68 | 58.69 | 5.27 |

| 12 months | 73.36 | 5.08 | 66.37 | 4.61 | 62.56 | 5.13 |

| QOL–Urinary Limitations Scale | ||||||

| Baseline | 98.16 | 0.99 | 98.87 | 0.57 | 98.27 | 0.87 |

| Postsurgery | ||||||

| 6 weeks | 80.11 | 3.36 | 75.76 | 3.26 | 77.57 | 3.41 |

| 6 months | 90.69 | 3.20 | 87.84 | 3.23 | 87.80 | 3.64 |

| 12 months | 91.15 | 3.52 | 89.81 | 3.13 | 91.54 | 3.23 |

| QOL–Urinary Bother Scale | ||||||

| Baseline | 91.56 | 1.92 | 93.14 | 1.55 | 88.54 | 2.16 |

| Postsurgery | ||||||

| 6 weeks | 65.87 | 4.37 | 62.08 | 4.22 | 65.72 | 4.39 |

| 6 months | 80.19 | 4.09 | 74.86 | 4.11 | 72.77 | 4.65 |

| 12 months | 79.62 | 4.47 | 80.15 | 4.08 | 82.01 | 4.53 |

| QOL–Sexual Function Scale | ||||||

| Baseline | 62.08 | 4.36 | 65.22 | 3.62 | 64.25 | 3.61 |

| Postsurgery | ||||||

| 6 weeks | 20.51 | 3.56 | 19.90 | 3.47 | 18.84 | 3.60 |

| 6 months | 29.50 | 3.56 | 30.32 | 3.39 | 23.93 | 3.87 |

| 12 months | 32.18 | 3.73 | 35.65 | 3.34 | 30.18 | 3.74 |

| QOL–Sexual Limitations Scale | ||||||

| Baseline | 92.55 | 1.68 | 96.15 | 0.97 | 94.23 | 1.22 |

| Postsurgery | ||||||

| 6 weeks | 79.61 | 2.79 | 77.07 | 2.72 | 78.91 | 2.80 |

| 6 months | 80.40 | 2.64 | 76.53 | 2.66 | 78.72 | 3.02 |

| 12 months | 81.20 | 2.96 | 77.85 | 2.66 | 82.22 | 2.89 |

| Sexual Bother Scale | ||||||

| Baseline | 78.03 | 2.82 | 81.82 | 2.31 | 76.74 | 2.82 |

| Postsurgery | ||||||

| 6 weeks | 56.09 | 4.56 | 47.15 | 4.51 | 49.53 | 4.73 |

| 6 months | 52.55 | 4.41 | 51.39 | 4.49 | 48.08 | 4.92 |

| 12 months | 51.94 | 4.68 | 53.00 | 4.42 | 55.50 | 4.82 |

| Bowel Function Scale | ||||||

| Baseline | 76.93 | 1.17 | 76.48 | 1.04 | 77.59 | 0.85 |

| Postsurgery | ||||||

| 6 weeks | 72.06 | 1.59 | 73.53 | 1.56 | 73.73 | 1.56 |

| 6 months | 73.02 | 1.48 | 73.94 | 1.51 | 75.81 | 1.72 |

| 12 months | 73.00 | 1.68 | 75.17 | 1.48 | 75.96 | 1.60 |

| Bowel Limitations Scale | ||||||

| Baseline | 99.90 | 0.10 | 99.51 | 0.35 | 99.40 | 0.37 |

| Postsurgery | ||||||

| 6 weeks | 97.20 | 0.87 | 98.13 | 0.84 | 97.81 | 0.85 |

| 6 months | 97.34 | 0.81 | 97.35 | 0.83 | 97.89 | 0.93 |

| 12 months | 96.17 | 0.91 | 98.35 | 0.80 | 98.95 | 0.87 |

| Bowel Bother Scale | ||||||

| Baseline | 70.01 | 0.93 | 70.69 | 0.90 | 70.01 | 0.92 |

| Postsurgery | ||||||

| 6 weeks | 66.85 | 1.43 | 66.82 | 1.43 | 66.89 | 1.38 |

| 6 months | 69.92 | 1.31 | 67.40 | 1.32 | 69.37 | 1.51 |

| 12 months | 67.38 | 1.50 | 68.74 | 1.29 | 69.03 | 1.44 |

| Cancer Worry Scale | ||||||

| Baseline | 58.88 | 4.51 | 62.43 | 4.53 | 56.35 | 4.37 |

| Postsurgery | ||||||

| 6 weeks | 59.45 | 4.55 | 70.42 | 4.32 | 68.51 | 4.46 |

| 6 months | 63.29 | 4.24 | 70.67 | 4.19 | 72.36 | 4.73 |

| 12 months | 69.30 | 4.60 | 75.95 | 4.14 | 76.02 | 4.59 |

NOTE. Follow-up means adjusted for age, ethnicity, baseline prostate-specific antigen, stage of disease, and baseline level of the outcome variable. Higher scores indicate better quality of life (QOL). There were no statistically significant group or group by time effects.

There were no group differences in pre-, peri- or postoperative complications, hospitalizations, or other medical complications in the year following surgery.

DISCUSSION

Our results are consistent with other studies that have shown beneficial effects of presurgical psychosocial interventions on mood and aspects of QOL in patients with cancer and other medical conditions.20–22,37–43 An important observation of our study was that the SM group, which was taught specific stress management skills, had better outcomes than did the SA group in terms of mood and QOL; in that the SM group was significantly different than the SC group but the SA group was not significantly different from either group in the posthoc comparisons.

Our results suggest modest effects for the primary outcome of mood disturbance before surgery. Although the group differences in POMS scores were in the hypothesized direction and were statistically significant, they were small and not likely clinically significant. The POMS, however, is not typically used as a clinical measure of mental health. The full clinical implications of reducing patients' mood disturbance presurgically needs further investigation as there is a link between distress, immune function, and wound healing time.22,45

The finding that such a brief intervention in the perioperative period was associated with better physical functioning 1 year later is intriguing and suggests the possibility that skills taught before surgery might have a lasting effect on patients' recovery and QOL. Although there were no significant differences in postoperative complications and hospitalizations, these were not controlled for in the analyses, nor were other comorbid conditions. In addition to showing statistically significant effects of the intervention on SF-36 PCS scores, the posthoc differences between the SM and SC groups were greater than half a standard deviation and likely clinically meaningful.44 As it is not exactly clear why such a brief intervention could lead to such a lasting effect on physical aspects of QOL, the findings need to be interpreted with caution. Future studies are needed to replicate these findings and explore potential meditators for the effects of the intervention.

Our hypothesis of detecting both short- and long-term group differences was supported, however, group differences were not apparent for all outcome variables. For example, the intervention had an effect on general physical aspects of QOL but not prostate cancer–specific QOL. It may be that the intervention was not powerful enough to affect the specific physical adverse effects of surgery, but improves overall QOL. In addition, this may also be due to the limited nature of the intervention and that the focus was on the perioperative period, with no intervention sessions focusing on adverse effects management once men were discharged from the hospital. There were also no group differences on mental health, as assessed by the SF-36 MCS and the IES, or long-term effects on mood. However, it is important to note that men in the study had high levels of mental health at study entry compared with normative data, and there were no statistically significant changes in these measures over time.

Some limitations should be noted. Participants were primarily white, non-Hispanic, married, and highly educated. Additional studies are needed with more diverse populations. The study was also conducted in men with early-stage disease, and the findings might be different in patients with more advanced disease. Additionally, this study did not target men at risk for distress before surgery. In fact, we excluded men with psychiatric diagnoses or who were undergoing psychotherapy. A targeted recruitment strategy focusing on highly distressed individuals might yield significant long-term effects on the mental health variables since including men who were more distressed at study entry may leave more room for improvement on mental health outcomes, although caution should be taken due to the brief nature of this intervention. Future research should examine whether there are subgroups of men for whom the intervention is most beneficial and whether the intervention could be adapted to other cancer populations. Our results suggest that providing patients with prostate cancer with a brief stress management intervention before surgery reduces mood disturbance before surgery and may enhance general physical aspects of QOL up to a year after surgery. There is a need to replicate these findings to determine whether or not this is a useful adjunct to standard care for men with prostate cancer undergoing surgery.

Acknowledgment

We thank Beth Notzon, BA, from the Office of Scientific Publications, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, for her helpful editorial comments on this article.

Footnotes

This research was supported by NIMH/NCI Grant No. RO1 MH59432.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Patricia A. Parker, Curtis A. Pettaway, Louis L. Pisters, Brian Miles, Danielle D. Carr, Lorenzo Cohen

Provision of study materials or patients: Curtis A. Pettaway, Richard J. Babaian, Louis L. Pisters, Brian Miles

Collection and assembly of data: Patricia A. Parker, Adoneca Fortier, Danielle D. Carr, Lorenzo Cohen

Data analysis and interpretation: Patricia A. Parker, Richard J. Babaian, Adoneca Fortier, Qi Wei, Lorenzo Cohen

Manuscript writing: Patricia A. Parker, Curtis A. Pettaway, Louis L. Pisters, Brian Miles, Qi Wei, Lorenzo Cohen

Final approval of manuscript: Patricia A. Parker, Curtis A. Pettaway, Richard J. Babaian, Louis L. Pisters, Brian Miles, Adoneca Fortier, Qi Wei, Danielle D. Carr, Lorenzo Cohen

REFERENCES

- 1.Aaronson NK, Meyerowitz BE, Bard M, et al. Quality of life research in oncology: Past achievements and future priorities. Cancer. 1991;67:839–843. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910201)67:3+<839::aid-cncr2820671415>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Litwin MS, Melmed GY, Nakazon T. Life after radical prostatectomy: A longitudinal study. J Urol. 2001;166:587–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melmed GY, Kwan L, Reid K, et al. Quality of life at the end of life: Trends in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Urology. 2002;59:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01457-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Litwin MS, Gore JL, Kwan L, et al. Quality of life after surgery, external beam irradiation, or brachytherapy for early-stage prostate cancer. Cancer. 2007;109:2239–2247. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ball AJ, Gambill B, Fabrizio MD, et al. Prospective longitudinal comparative study of early health-related quality-of-life outcomes in patients undergoing surgical treatment for localized prostate cancer: A short-term evaluation of five approaches from a single institution. J Endourol. 2006;20:723–731. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.20.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eton DT, Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS. Early quality of life in patients with localized prostate carcinoma: An examination of treatment-related, demographic, and psychosocial factors. Cancer. 2001;92:1451–1459. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6<1451::aid-cncr1469>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eton DT, Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS. Psychological distress in spouses of men treated for early-stage prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:2412–2418. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helgeson VS, Lepore SJ, Eton DT. Moderators of the benefits of psychoeducational interventions for men with prostate cancer. Health Psychol. 2006;25:348–354. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.3.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS, Eton DT, et al. Improving quality of life in men with prostate cancer: A randomized controlled trial of group education interventions. Health Psychol. 2003;22:443–452. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts KJ, Lepore SJ, Helgeson V. Social-cognitive correlates of adjustment to prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:183–192. doi: 10.1002/pon.934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Kraemer HC, et al. Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet. 1989;2:888–891. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell LC, Keefe FJ, Scipio C, et al. Facilitating research participation and improving quality of life for African American prostate cancer survivors and their intimate partners: A pilot study of telephone-based coping skills training. Cancer. 2007;109:414–424. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giesler RB, Given B, Given CW, et al. Improving the quality of life of patients with prostate carcinoma: A randomized trial testing the efficacy of a nurse-driven intervention. Cancer. 2005;104:752–762. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlson LE, Speca M, Patel KD, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in relation to quality of life, mood, symptoms of stress, and immune parameters in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:571–581. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000074003.35911.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penedo FJ, Dahn JR, Molton I, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management improves stress-management skills and quality of life in men recovering from treatment of prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100:192–200. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer TJ, Mark MM. Effects of psychosocial interventions with adult cancer patients: A meta-analysis of randomized experiments. Health Psychol. 1995;14:101–108. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fawzy FI, Fawzy NW, Arndt LA, et al. Critical review of psychosocial interventions in cancer care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:100–113. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950140018003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mishel MH, Germino BB, Belyea M, et al. Moderators of an uncertainty management intervention: For men with localized prostate cancer. Nurs Res. 2003;52:89–97. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penedo FJ, Molton I, Dahn JR, et al. A randomized clinical trial of group-based cognitive-behavioral stress management in localized prostate cancer: Development of stress management skills improves quality of life and benefit finding. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31:261–270. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3103_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burton MV, Parker RW, Farrell A, et al. A randomized controlled trial of preoperative psychological preparation for mastectomy. Psychooncology. 1995;4:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams PD, Valderrama DM, Gloria MD, et al. Effects of preparation for mastectomy/hysterectomy on women's post-operative self-care behaviors. Int J Nurs Stud. 1988;25:191–206. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(88)90046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larson MR, Duberstein PR, Talbot NL, et al. A presurgical psychosocial intervention for breast cancer patients: Psychological distress and the immune response. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludwick-Rosenthal R, Neufeld WJ. Stress management during noxious medical procedures: An evaluation review of outcome studies. Psychol Bull. 1988;104:326–342. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.104.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson JE. Psychological interventions and coping with surgery. In: Baum A, Taylor SE, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of Psychology and Health. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1984. pp. 167–188. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng SK, Chau AW, Leung WK. The effect of pre-operative information in relieving anxiety in oral surgery patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:227–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manyande A, Berg S, Gettins D, et al. Preoperative rehearsal of active coping imagery influences subjective and hormonal responses to abdominal surgery. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:177–182. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199503000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manyande A, Chayen S, Priyakumar P, et al. Anxiety and endocrine responses to surgery: Paradoxical effects of preoperative relaxation training. Psychosom Med. 1992;54:275–287. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199205000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kshettry VR, Carole LF, Henly SJ, et al. Complementary alternative medical therapies for heart surgery patients: Feasibility, safety, and impact. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pocock SJ. Clinical Trials: A Practical Approach. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antoni M, Baggett L, Ironson G, et al. Cognitive behavioral stress management intervention buffers distress responses and elevates immunologic markers following notification of HIV-1 seropositivity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:906–915. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cella DF, Jacobsen PB, Orav EJ, et al. A brief POMS measure of distress for cancer patients. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:939–942. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ware J, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, et al. SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Centre Hospitals, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Litwin MS, Hays RD, Fink A, et al. The UCLA Prostate Cancer Index: Development, reliability, and validity of a health-related quality of life measure. Med Care. 1998;36:1002–1012. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson JE, Leventhal H. Effects of accurate expectations and behavioral instructions on reactions during a noxious medical examination. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1974;29:710–718. doi: 10.1037/h0036555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Langer EJ, Janis IL, Wolfer JA. Reduction of psychological stress in surgical patients. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1975;11:155–165. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kendall PC, Williams L, Pechacek TF, et al. Cognitive-behavioral and patient education interventions in cardiac catheterization procedures: The Palo Alto Medical Psychology Project. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson EA. Preoperative preparation for cardiac surgery facilitates recovery, reduces psychological distress, and reduces the incidence of acute postoperative hypertension. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:513–520. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ludwick-Rosenthal R, Neufeld RW. Preparation for undergoing an invasive medical procedure: Interacting effects of information and coping style. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:156–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lang EV, Berbaum KS, Faintuch S, et al. Adjunctive self-hypnotic relaxation for outpatient medical procedures: A prospective randomized trial with women undergoing large-core breast biopsy. Pain. 2006;126:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lang EV, Benotsch EG, Fick LJ, et al. Adjunctive non-pharmacological analgesia for invasive medical procedures: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1486–1490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sloan JA, Frost MH, Berzon R, et al. The clinical significance of quality of life assessments in oncology: A summary for clinicians. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:988–998. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0085-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Christian LM, Graham JE, Padgett DA, et al. Stress and wound healing. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2006;13:337–346. doi: 10.1159/000104862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]