Abstract

Murine models of coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3)-induced myocarditis mimic the divergent human disease course of cardiotropic viral infection, with host-specific outcomes ranging from complete recovery in resistant mice to chronic disease in susceptible hosts. To identify susceptibility factors that modulate the course of viral myocarditis, we show that type-I interferon (IFN) responses are considerably impaired in acute CVB3-induced myocarditis in susceptible mice, which have been linked to immunoproteasome (IP) formation. Here we report that in concurrence with distinctive type-I IFN kinetics, myocardial IP formation peaked early after infection in resistant mice and was postponed with maximum IP expression concomitant to massive inflammation and predominant type-II IFN responses in susceptible mice. IP activity is linked to a strong enhancement of antigenic viral peptide presentation. To investigate the impact of myocardial IPs in CVB3-induced myocarditis, we identified two novel CVB3 T cell epitopes, virus capsid protein 2 [285-293] and polymerase 3D [2170-2177]. Analysis of myocardial IPs in CVB3-induced myocarditis revealed that myocardial IP expression resulted in efficient epitope generation. As opposed to the susceptible host, myocardial IP expression at early stages of disease corresponded to enhanced CVB3 epitope generation in the hearts of resistant mice. We propose that this process may precondition the infected heart for adaptive immune responses. In conclusion, type-I IFN-induced myocardial IP activity at early stages coincides with less severe disease manifestation in CVB3-induced myocarditis.

Myocarditis is often induced by cardiotropic viruses: in about 20% of patients, viral myocarditis leads to its sequela dilated cardiomyopathy, which is linked to chronic inflammation and persistence of cardiotropic viruses.1,2,3,4 Dilated cardiomyopathy is the most common cause of heart failure in young patients and appears to be a major cause of sudden unexpected death in this cohort. Enteroviruses, including group-B coxsackieviruses, have been linked to the development of myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy associated with adverse prognosis.5,6 Well-established murine models of coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) myocarditis mimic the human disease progress and are valuable in delineating the underlying mechanisms that determine the divergent courses of myocarditis7,8,9,10: resistant C57BL/6 mice eliminate the virus following mild acute myocarditis; no chronic inflammation is detected. In contrast, major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-matched A.BY/SnJ mice develop severe acute infection and ongoing chronic myocarditis, thus conferring susceptibility to chronic disease.7,9

Host responses to viral infection trigger the release of interferons (IFNs). IFNs of the α/β subtype are assigned to type I IFNs, whereas IFN-γ is the only type II IFN. IFNs exert numerous antiviral effects in innate and adaptive immunity.11 Although type I IFN-receptor-deficiency was not associated with a dramatic effect on early viral replication in the heart, type I IFN signaling was found to be essential for the prevention of early death due to CVB3-infection.12 The extraordinary impact of type I IFNs was substantiated in a recent study illustrating acute fulminant infection and chronic disease progression in IFN-β deficient mice.13 Deletion of type II IFN receptors was not associated with enhanced mortality in CVB3-infection.12 IFN-γ responses were shown to be protective in cellular immunity in CVB3-infection.9 In addition, expression of IFN-γ conferred protection in enterovirus myocarditis, which may be linked to the activation of nitric oxide-mediated antiviral activity of macrophages.14,15 Thus, both type I and type II IFN are active in CVB3- myocarditis.

One downstream effect of IFN signaling is the induction of immunoproteasome (IP) formation in the target organ of the immune response. Particularly IFN-γ was shown to induce IP expression.16,17,18 Efficient generation of viral epitopes that stimulate CD8+ T cells strongly relies on host-cell IP and, in addition, protein degradation by proteasomes is also essential in the regulation of inflammatory and stress responses, cell cyclus, and apoptosis control.19 The 20S proteasome as the catalytic core of the proteasome resembles a cylinder-shaped structure of stacked heptameric rings formed by either α or β subunits. The proteolytic function of the so-called standard proteasome is restricted to the β1, β2, and β5 subunit.20 Three alternative catalytic subunits, the so-called immunosubunits β1i, β2i, and β5i, which are incorporated into 20S proteasomes, thus forming IP with altered catalytic characteristics, are expressed on cytokine stimulation.21,22 It is highly notable that IP activity is linked to a strong enhancement of antigenic viral peptide presentation.23,24,25,26,27

Cardiac proteasomes contribute to the modulation of cardiac function in health and disease.28 However, apart from the reported observation that IPs are expressed in the myocardium in acute CVB3 myocarditis, their functional impact has not been studied so far.10 The present study focuses on IFN-induced myocardial IP activity in CVB3 myocarditis.

Materials and Methods

Virus and Mice

CVB3 (cardiotropic Nancy strain) used in this study was prepared as previously described.29 C57BL/6 and A.BY/SnJ mice (both H-2b haplotype) were kept at the animal facilities of the Charité University Medical Center and at the Department of Molecular Pathology in Tuebingen, Germany. All experiments were conducted according to the German Animal Protection Act. Six week-old (equal distribution of both sexes) were infected i.p. with 1 × 105 plaque-forming units of purified CVB3 as described previously.10

In Situ Hybridization

CVB3 positive-strand genomic RNA in tissues was detected using single-stranded 35S-labeled RNA probes as described previously.8 Slide preparations were subjected to autoradiography, exposed for 3 weeks at 4°C, and counterstained with H&E.

Proteasome Purification

Hearts of infected mice and uninfected controls were homogenized in 20 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.2, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L NaN3, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.5% NP40, and protease-inhibitor cocktail (Complete, Roche). Further purification was performed as described recently.30

Cell Lines

Immortalized cardiomyocyte HL-1 cells were generated by Dr. William Claycomb, and cells were grown according to Claycomb’s instructions.31 Cells were incubated with IFN-γ and IFN-β at 50 U/ml for the time points indicated.

Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR

Total RNA from murine hearts or HL-1 cells was isolated using TRIzol reagent. A total of 500 ng RNA was DNase-digested (Ambion) and reverse-transcribed with MMLV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR for β1i, β5i, β2i, α5, and CVB3 was performed as described recently.10,32 For transporter associated with antigen presentation (TAP)-1, 2,5 oligoadenylate synthetase-like 2 (OASL-2), and MHC class I, quantitative PCR was performed using primers and probes of TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (ABI). Pre-amplification of cDNA samples was performed by applying the TaqMan PreAmp Master Mix (ABI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for analysis of IFN expression. mRNA expression was normalized to the housekeeping gene hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase by means of the δCt method, and to expression in individual controls by use of the comparative δδCt method. All data are shown as mean of at least three individual mice ± SEM.

Immunoblot Analysis

Immunoblot analysis was performed as described previously.33 Antibodies used for immunoblot were: ab3328 (Abcam) and #62966 (β1i), K63/5 (β5i), K65/4 (β2i), K378 (α4), and sc-25778 (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase).

Pentamer Staining

H-2b-phycoerythrin (PE) pentamers for virus capsid protein 2 (VP2) [285-293] and polymerase 3D (P3D) [2170-2177] were purchased from ProImmune (Oxford, UK). CD8 T cells were enriched from single-cell suspensions of splenocytes and peripheral lymph nodes of CVB3-infected and uninfected control mice by CD8 microbeads (Miltenyi, Germany). CD8 T cells were stained according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Pentamer-PE, CD8 α-fluorescein isothiocyanate, CD19-PE Cy5). Pentamer stain was performed for 15 minutes at room temperature. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting-analysis was performed on a FACSCalibur (BD, Germany). CD19-positive B cells were excluded from the analysis.

Determination of Cytokines by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Single-cell suspensions of T cells (1 × 106/ml) enriched from spleens of CVB3-infected and uninfected mice were isolated at day 8 p.i. and co-cultured with peptide-loaded (5 μg/ml) or sham-treated bone marrow macrophages (5 × 105/ml) isolated from uninfected C57BL/6 and A.BY/SnJ mice, respectively. Determination of IL-2 and IFN-γ levels was performed in culture supernatants by an OptEIA kit (Becton-Dickinson) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with the modification that 50 μl of supernatants was incubated overnight at 4°C.

In Vitro Degradation and Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Peptides

Polypeptides harboring VP2 [285-293] and P3D [2170-2177] (3 μg each) were incubated with 1 μg proteasome in 100 μl 20 mmol/L Hepes, pH 7.8, 2 mmol/L Mg-acetate, 2 mmol/L dithiothreitol at 37°C for the indicated time points. Samples were analyzed by reverse phase-high performance liquid chromatography; the HP1100 system (Hewlett-Packard, Germany) equipped with a RPC C2/C18 SC 2.1/10 column (GE Health care, Germany). Analysis was performed online with a LCQ ion trap mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ion source (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany).

MHC Binding Characteristics of VP2 [285-293] (FRHNNVTLM) of P3D [2170-2177] (TLPAFSTL)

RMA-S cells were cultured in supplemented RPMI medium. Relative affinity (RA) of peptides to MHC class I and stability (DC50) of MHC class I ligands complexes were determined as described elsewhere.28 For affinity studies, stripped RMA-S cells were incubated with various peptide concentrations (100.0, 50.0, 5.0, 2.5, 0.5 μg/ml) overnight in serum-free medium supplemented with 1.5 μg/ml β2 microglobulin. For MHC class I stability, RMA-S cells were incubated with 100 μg/ml peptide overnight, washed, and cultured in the presence of brefeldin A for 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 hours. All cells were stained with H-2Db-PE (BD clone: KH95) and H-2Kb-PE (BD clone: AF6-88.5) mAb.

Maximal binding capacity is defined as binding of a reference peptide at 100 μmol/L. RA was determined for each peptide concentration as follows: RA = peptide concentration of peptide of interest at 20% of maximal binding capacity/peptide concentration of reference peptide at 20% of maximal binding capacity. A low RA (RA <10) suggest high affinity binding of peptides to MHC class I molecules.

Dissociation complex DC50 is defined as the time needed to destabilize 50% of initially formed peptide/MHC complexes at time t = 0 hours. A higher DC50 suggest a more stable complex.

VP2 [285-293] exhibited high binding affinity as determined with use of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus FQPQNGQFI peptide as reference: RA of VP2 [285-293] was 0.7 ± 0.1 and DC50 >2 hours (DC50 is the time where 50% of the peptide MHC complexes are dissociated). SIINFEKL from ovalbumin served as reference peptide for P3D [2170-2177]: DC50 of P3D [2170-2177] was found to be less than 1 hour. However, P3D [2170-2177] exhibited a relative affinity of 7.1 ± 4.7, which suggests an appropriate binding to MHC class I molecules.

Statistics

Results of continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SEM. Two group comparisons of nonparametric data were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. The t-test was used for normally distributed variables. Significance was assessed at the P < 0.05 level.

Results

IFN Response in Murine Enterovirus Myocarditis

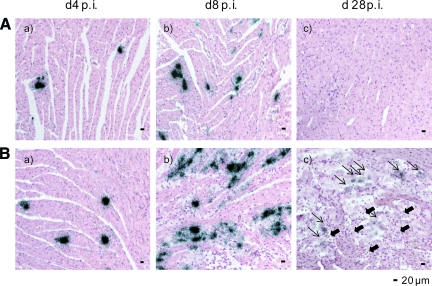

Immunocompetent C57BL/6 and A.BY/SnJ mice show distinctive cardiac phenotypes following CVB3 infection.7,10 At the early stage of infection (day 4 p.i.), single in situ CVB3-positive cardiomyocytes were found in the myocardium in the absence of histological evidence of inflammation [Figure 1A(a)+B(a)]. At day 8 p.i., infected cardiomyocytes adjacent to foci of mononuclear cell infiltrates are pathognomonic for acute heart muscle injury [Figure 1A(b)+B(b)]. Myocarditis in susceptible mice appeared to be more severe.34 As a consequence of virus elimination in C57BL/6 mice, no ongoing cardiac inflammation was noted in resistant mice at day 28 p.i. [Figure 1A(c)]. Persistent virus infection and consecutively chronic myocarditis in A.BY/SnJ mice at day 28 p.i. [Figure 1B(c)] resembles the chronic disease progress of virus-induced cardiomyopathy in humans. CVB3 replication in the myocardium was determined by real-time PCR (see supplemental Figure 1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org) indicating more pronounced viral load in A.BY/SnJ mice. In accordance, in a recent study we quantified the area fraction of infection obtained by CVB3 in situ hybridization in heart tissue sections confirming above mentioned findings.34

Figure 1.

Murine mouse model of enterovirus myocarditis. A/B: Time course of CVB3 infection as determined by CVB3 in situ hybridization and H&E staining in the hearts of C57BL/6 (A) and A.BY/SnJ (B) mice, indicating viral load (black dots) and inflammatory lesions predominantly at day 8 post-infection (p.i.). (a) day 4 p.i., (b) day 8 p.i. (c) day 28 p.i. B (c): Short, filled arrows pointing left indicate inflammatory lesions; long arrows pointing right indicate positive CVB3 in situ hybridization signals. All cardiac tissue sections shown are representatives of at least three mice.

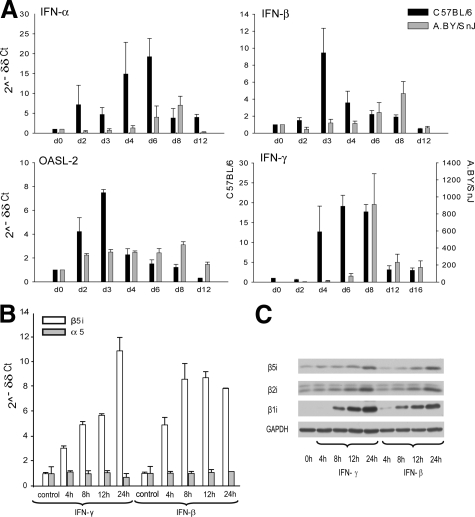

In an attempt to determine susceptibility factors to ongoing myocarditis, we studied IFN expression patterns in the time course of infection in the infected myocardium. CBV3-infection in C57BL/6 mice induced early and rapid up-regulation of IFN-α and IFN-β mRNA expression in murine hearts (Figure 2A). The expression of IFN-α mRNA rapidly increased as early as at day 2 p.i. in C57BL/6 mice, whereas it was enhanced in A.BY/SnJ mice not before day 6 p.i., with an overall less-pronounced IFN-α expression in this strain. IFN-β mRNA expression peaked at day 3 p.i. and declined toward day 6 p.i. In contrast, expression of IFN-β in susceptible ABY/SnJ mice was delayed and diminished with maximal mRNA expression levels at day 8 p.i. Type I IFN dependent downstream-regulation of OASL-2 followed the same expression kinetics as both type I IFNs, thus supporting the differential type I IFN response in both mice on CVB3 infection (Figure 2A). During the chronic stage of infection at day 28 p.i., type I IFN-expression was not enhanced in any host (data not shown). In contrast to differential type I IFN mRNA expression kinetics, IFN-γ mRNA expression peaked at the acute stage of myocarditis, concomitant to myocardial invasion of inflammatory cells in both strains (Figure 2A). IFN-γ secretion is predominantly due to the invasion of macrophages and T cells. In mice susceptible to chronic disease, IFN-γ mRNA expression was found to be dramatically increased at the acute stage of infection, which is in concordance with massive inflammation in A.BY/SnJ mice in acute myocarditis (Figure 1Bb,34).

Figure 2.

IFN response in CVB3 myocarditis. A: Real-time PCR: IFN-α, IFN-β, OASL-2, and IFN-γ mRNA expression in the hearts of CVB3-infected C57BL/6 (black bars) and A.BY/SnJ (gray bars) mice during the infection course. Note the different scaling for IFN-γ mRNA expression: left y axis C57BL/6; right y axis: A.BY/SnJ. Data are means of at three individual mice + SEM. B/C: IFN-γ and IFN-β induce the expression of IP subunits in HL-1 cells. HL-1 cells were stimulated with IFN-γ and IFN-β for the time points indicated. B: Up-regulation of β5i expression as determined by real-time PCR: mRNA expression of constitutive proteasome subunit α5 indicates steady-state levels of proteasome amount. C: Immunoblot analysis of HL-1 cells indicates enhanced synthesis and incorporation of immunosubunits β5i, β2i, and β1i into the proteasome core complex.

Immunoproteasome (IP) formation, which is crucial for effective antigen processing,23,24,25,26,27 was shown to be linked to type I IFN16 and type II IFN responses.17,18 To investigate a potential impact of IFNs on IP formation also in cardiomyocytes, as a proof-of-principle experiment HL-1 cardiomyocyte cell line was exposed to exogenous IFN-β and IFN-γ (the latter being the classical inductor of IP synthesis in vitro). Both IFN-β and IFN-γ in fact induced the mRNA and protein expression of the proteasomal immunosubunits β1i, β2i, and β5i in the HL-1 cardiomyocytes in a time dependent manner (Figure 2, B and C).

Expression of Cardiac IPs in the Course of CVB3 Infection

Earlier studies revealed that IP expression is more pronounced in susceptible mice at the peak of inflammation and destruction of the heart,10 which is unequivocally concomitant to peak IFN-γ responses in the myocardium (Figure 2A). Taking the type I IFN-dependent induction of IP in hepatitis C into account,16 type I IFN expression patterns in resistant mice further evoked the question, whether IP formation may also follow different kinetics in both hosts.

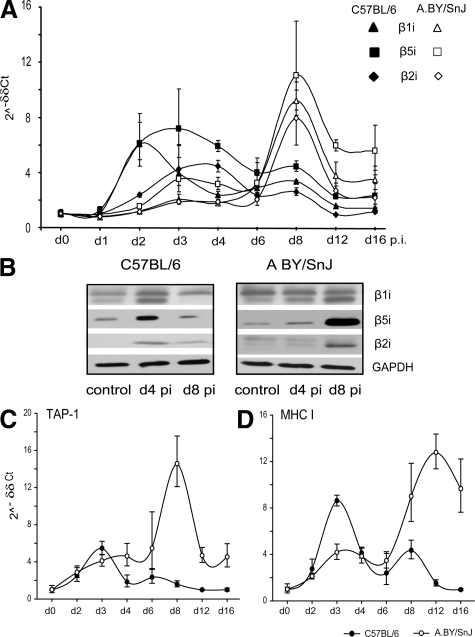

To study the kinetics of IP synthesis during the course of CVB3 infection in the heart, mRNA expression of the immunosubunits β1i, β2i, and β5i was determined at different time points after CVB3 infection (Figure 3A). Whereas A.BY/SnJ mice exhibited an IP expression maximum at day 8 p.i., immunosubunit expression peaked between day 2 and 4 p.i.in the hearts of C57BL/6 mice, and considerably declined toward day 8 p.i. The respective immunosubunit protein content in cardiac tissue lysates again illustrated time-dependent myocardial IP formation in infected mice (Figure 3B). Mouse-strain–specific type I IFN expression kinetics in C57BL/6 mice thus perfectly agrees with the differential expression of heart IPs at early stages of CVB3 myocarditis. Notably, IP content reached basic expression levels in both mouse strains at 28 days p.i.10

Figure 3.

IP expression in CVB3 myocarditis. A: Real-time PCR: β1i, β5i, and β2i mRNA expression in the hearts of CVB3-infected C57BL/6 (filled symbols) and A.BY/SnJ (open symbols) mice. Data are means of at least three individual mice ± SEM. B: Immunoblot analysis of cardiac tissue homogenates of uninfected mice (control) and CVB3-infected mice at day 4 and 8 p.i., indicating expression of immunosubunits β1i, β5i, and β2i in myocarditis. Experiments were performed with homogenates obtained from individual mice and repeated at least four times showing the same results. C/D: Real-time PCR: TAP-1 (C) and MHC class I (D) mRNA expression in the hearts of CVB3-infected C57BL/6 (filled circles) and A.BY/SnJ (open circles) mice. Data are means of at three individual mice ± SEM.

Interestingly, cardiac IP expression in C57BL/6 mice peaks at early stages around day 4 p.i., despite the absence of a relevant migration of inflammatory cells into CVB3-infected hearts at this time point. Therefore, in agreement with our recent study showing an up-regulation of iβ5 mRNA expression in cardiomyocytes during CVB3 myocarditis,10 our present data point to a remarkable contribution of cardiomyocytes to the IP pool during infection.

In addition to IP, TAP peptide transporters and MHC class I molecules are essential for the presentation of viral epitopes to elicit efficient CD8+ T cell responses.19 Cardiac mRNA expression of both TAP-1 and MHC class I was up-regulated in C57BL/6 and A.BY/SnJ mice (Figure 3, C and D), in parallel with the expression kinetics shown above for cardiac IPs. The infected myocardium therefore exhibits the characteristics of a T cell target in preparing for the effective presentation of viral epitopes.

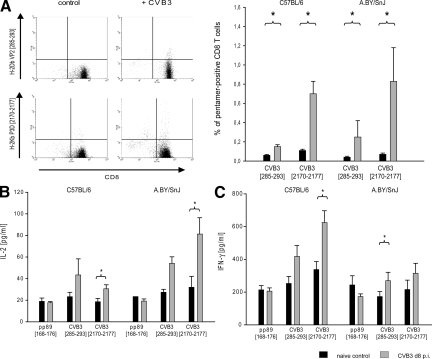

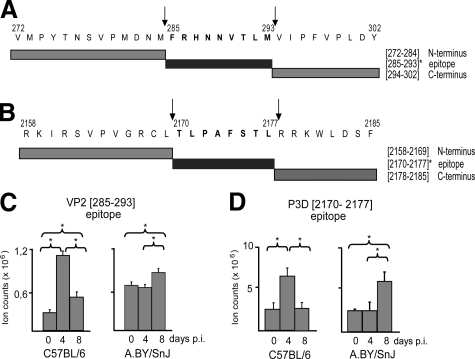

Identification of VP2 [285-293] and P3D [2170-2177] as CVB3 Epitopes

To study the functional impact of myocardial IP formation in myocarditis, knowledge of viral epitopes against which a specific CD8+ T cell response is mounted is required. For CVB3, however, no such epitopes have been identified so far. To search for CVB3 epitopes, we applied the SYFPEITHI prediction program for viral proteome analysis to select potential epitopes.35 MHC class I binding studies revealed two potential candidate peptides: H-2Db restricted peptide VP2 [285-293] (FRHNNVTLM) from VP2, and H-2Kb restricted peptide P3D [2170- 2177] (TLPAFSTL) from RNA-directed RNA P3D (see supplemental Figure 1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). To study the immunogenic potential of theses peptide, information about epitope-specific CD8 T cell responses were acquired by H-2b pentamer staining. As depicted in Figure 4A, CD8 T cell responses are mounted particularly against P3D [2170-2177] in both hosts. VP2 [285-293]-specific CD8 T cell frequencies were considerably low. Absolute epitope-specific CD8 T cell numbers did not differ between C57BL/6 and A.BY/SnJ mice. Consequently, our data are indicative for the immunogenic potential of P3D [2170-2177] and potentially also for VP2 [285-293] epitopes to elicit CD8 T cell responses in CVB3 infection.

Figure 4.

Viral epitope-specific T cell responses in acute myocarditis. A: Pentamer staining of VP2 [285-293] and P3D [2170-2177] CD8 T cells. Mice were sacrificed at day 8 p.i. CD8 T cells were stained with H-2Db VP2 [285-293]-PE and H-2Kb P3D [2170-2177]-PE. T cells from uninfected mice served as negative controls. Left panel: representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis staining is shown for each pentamer. Cells in the upper right quadrant indicate epitope-specific CD8 T cell population. Right panel: Pentamer-positive CD8 T cell frequencies are shown for VP2 [285-293] and P3D [2170-2177]. B/C: Functional impact of epitope-specific CD8 T cells in acute myocarditis: analysis of cytokine release of T cells after stimulation with VP2 [285-293] and P3D [2170-2177] is shown. T cells from CVB3-infected mice were co-cultured with peptide-pulsed bone marrow macrophages. (B) IL-2 and (C) IFN-γ production was detected by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. YPHFMPTNL from MCMV pp89 [168–176] served as a control peptide. All data are shown as mean of at least four individual mice + SEM. *P < 0.05.

Proceeding beyond the detection of epitope-specific T cells [quantitative information], we next studied the functional capacities of these CD8 T cells to induce IFN-γ and IL-2 secretion in ex vivo antigen presentation assays [qualitative information]. Indeed, both P3D [2170-2177] and VP2 [285-293] induced the secretion of IFN-γ and IL-2 by peptide-specific T cells from CVB3-infected mice (Figure 4, B and C). MCMV derived epitope YPHFMPTNL served as an internal control, which did not reveal any cytokine release by CVB3-specific T cells. IFN-γ release was enhanced by T cells derived from C57BL/6 mice, whereas IL-2 production was more pronounced by T cells from A.BY/SnJ mice. Overall T cell activation of P3D [2170-2177] epitope-specific T cells was markedly enhanced in comparison with VP2 [285-293]-specific T cells, thus being in concurrence to considerably enhanced CD8 T cell frequencies of P3D [2170-2177]-specific T cells.

Myocardial IP Activity Is Linked to Enhanced Epitope Generation in CVB3 Myocarditis

To investigate whether these CVB3 epitopes are generated by myocardial proteasomes, polypeptides harboring the predicted CVB3 epitopes (31mer polypeptide VP2 [272–302] and 28mer polypeptide P3D [2158- 2185], Figure 5, A and B) were applied to proteasome-dependent in vitro processing studies. We performed degradation assays using myocardial 20S proteasomes isolated from the hearts of CVB3-infected C57BL/6 and A.BY/SnJ mice at different time points after infection. As shown in Figure 5, C and D, both epitopes were indeed generated by myocardial proteasomes. Generation of both the H-2Db-restricted VP2 [285-293] and the H-2Kb-restricted P3D [2170-2177] epitope by myocardial proteasomes from CVB3-infected C57BL/6 mice was significantly enhanced at day 4 p.i. and declined toward day 8 p.i. (Figure 5, C and D). Myocardial proteasomal degradation of epitope-harboring peptides revealed a fourfold greater generation of VP2 [285-293] and 2.6-fold increase in P3D [2170-2177] generation at day 4 p.i. in C57BL/6 mice, compared with the uninfected control. Myocardial proteasomes from day 4 p.i. of A.BY/SnJ mice did not affect epitope liberation in comparison with proteasomes from naïve mice. On the other hand, peptide-processing investigations performed with cardiac proteasomes isolated 8 days p.i. from susceptible A.BY/SnJ mice revealed a 1.4-fold increase for VP2 [285-293] and 1.9-fold increase for P3D [2170-2177] epitope generation. Proteasomes from both strains evidently generated VP2 [285-293] less efficiently than they did P3D [2170-2177].

Figure 5.

Myocardial IP activity is linked to enhanced epitope generation in CVB3 myocarditis. A: Sequences of the 31mer peptide substrate VP2 [272–302] spanning VP2 [285-293] and selected proteasomal cleavage products are shown. Arrows indicate epitope cleavage sites. B: The amino acid sequence of the 28mer peptide substrate P3D [2158–2185], the generated epitope P3D [2170-2177], and epitope-flanking peptides are shown. C/D: Proteasomes were isolated from the hearts of C57BL/6 and A.BY/SnJ mice during CVB3 myocarditis (day 0, 4, and 8 p.i., n = 10) and processing studies were performed with epitope-harboring peptides (C) VP2 [272–302] and (D) P3D [2158–2185] The amount of epitope generation was estimated by LC-ESI-MS. Normalized ion counts are shown. Data are means of at least three independent replicates + SEM. *P < 0.05.

In total, these experiments perfectly agree with the kinetics of type I IFN-induced IP expression early on infection in C57BL/6 mice and with the delayed myocardial IP expression peak later on infection, which is concomitant with massive invasion of inflammatory cells in A.BY/SnJ mice.

Discussion

In the present study, myocardial type I IFN response was found to be delayed and diminished in mice that develop severe acute myocarditis and consecutively ongoing chronic disease. Type I IFN host-specific expression in C57BL/6 mice was linked to myocardial IP formation early on CVB3-infection, which was likewise shown to enhance the liberation of antigenic peptides at early stages of viral myocarditis. CVB3-epitope generation by myocardial IP and the expression of other components of antigen presentation machinery were delayed in viral myocarditis in A.BY/SnJ mice coinciding with more severe disease manifestation.

Host responses to viral infection trigger IFN release. Initial studies with cultured cells have suggested that both type I and type II IFNs can inhibit coxsackievirus replication.36 IFNs bind exclusively to their respective receptors. Genetic disruption of the type I or type II IFN receptors completely and specifically abolishes the biological effects of type I and type II IFNs, respectively.37,38 Distinct support for the impact of type I and type II IFN signaling in viral myocarditis was provided in a study by Wessely et al that investigated CVB3-infection in type I and type II IFN receptor-deficient mice. Although type I and type II IFN signaling did not affect viral replication in the heart, type I IFN receptor defects were associated with early death due to CVB3-infection, whereas type II IFN receptor deficiency did not have an impact on survival.12 Accordingly, depression of IFN-β responses resulted in acute fulminant infection and chronic disease progression on CVB3 infection, thus resembling the cardiac phenotype observed in susceptible A.BY/SnJ wild-type mice in this study. In contrast to resistant C57BL/6 mice, type I IFN expression was accordingly found to be impaired in the infected heart in susceptible A.BY/SnJ mice being in perfect agreement with the aforementioned disease courses in INF-β deficient mice.13 Earlier studies revealed quantitative differences in IFN-α and IFN-β gene expression in C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice due to different genotypes in the If-1 locus.39 Chronic inflammation in CVB3-infected BALB/c mice resembles the disease manifestation observed here in A.BY/SnJ mice.40 Therefore, genetic predisposition may be involved in type I IFN response patterns on viral infection.

Whereas type II IFN receptor deficiency did not affect survival,12 IFN-γ responses were shown to be protective against CVB3 in the adaptive immune response in CVB3-myocarditis. CD8 T cells in enterovirus myocarditis were shown to exert their antiviral potential particularly by the secretion of IFN-γ.9 In addition, expression of immunoregulatory IFN-γ conferred protection in enterovirus myocarditis, which may be linked to the activation of nitric oxide-mediated antiviral activity of macrophages.14,15 Accordingly, sustained nitric-oxide synthesis contributes to immunopathology in ongoing myocarditis in susceptible A.BY/SnJ mice.34 IFN-γ mRNA expression data as shown here are indicative for maximum levels of IFN-γ secretion concomitant with the peak of inflammatory lesions in both hosts. Pronounced inflammatory lesions at day 8 p.i. in A.BY/SnJ mice (Figure 1Bb;34) perfectly agree with enhanced IFN-γ mRNA expression levels in susceptible A.BY/SnJ mice (Figure 2A).

One downstream effect of IFN signaling is the induction of IP formation in the target organ of the immune response.19 In agreement with data obtained in hepatitis C, which show a type I IFN-induced IP formation early on infection,16 our present study revealed a concomitant cardiac type I IFN response and myocardial IP formation, as well as enhanced expression of compounds of the antigen presentation machinery at early stages of CVB3 myocarditis in C57BL/6 mice. IFN-γ is also known to be a potent inducer of IP17,19 and appears to be the predominant cytokine to stimulate IP formation in susceptible mice: IP expression peaked in parallel to maximum IFN-γ mRNA expression and invasion of inflammatory cells.

IP exhibit enhanced protease activities and altered cleavage site preferences resulting in efficient liberation of many MHC class I epitopes.19 Detailed studies on the functional importance of IP revealed that in particular the generation and presentation of viral epitopes is strongly enhanced in the presence of IP and that their function is tightly connected with the early phases of an antiviral immune response.17,18,24 However, the role of IP in the myocardium has not been studied so far. In support of the existing the well-established picture of IP function in viral infection, myocardial IP expression in CVB3 myocarditis as shown here resulted in the enhanced generation of two newly identified CVB3 epitopes, VP2 [285-293] and P3D [2170-2177]. The concomitant induction of MHC class I molecules and TAP-1 peptide transporters in the infected myocardium suggests that the heart, an organ adapted to complex modulation of contractile function, complies with the requirements for an effective immune response in viral infection.

In the pathogenesis of chronic enterovirus myocarditis, the failure of the host’s immune system to eliminate the virus during acute infection seems to be crucial. In accordance with the impact of type I IFN responses in enterovirus-myocarditis,12,13 findings of the present study point to a potential impact of IP activity on the severity of myocarditis: in concert with the postponed type I IFN response, IP-dependent CVB3 epitope generation was delayed to stages where excessive inflammation concomitant the high viral load were already present. The emerging picture of proteasomal activity reveals that early antigen-processing determines the ability of pathogen-derived peptides to elicit a CD8 T cell response.18,41 Due to low basal IP expression the absolute quantities of generated T- cell epitopes seem to be particularly low in the noninfected heart.42 Thus, efficient viral epitope processing by cardiac IP and epitope presentation in infected cardiomyocytes seem to be crucial in the battle of the virus to render CVB3-infected cells invisible to CD8 T cells by down-regulation of the antigen presentation machinery.43,44 Taking the considerably low CVB3-specific CD8 T cell frequencies into account, efficient epitope presentation by infected cardiomyocytes appears to be important for these infected cells to be recognized by epitope-specific T cells. Thus, we assume that IP activity in virus-infected cardiomyocytes early on infection in resistant C57BL/6 mice supports efficient antigen presentation and consecutive clearance of infected cardiomyocytes by CD8 T cells.

The remarkable role of CD8 T cells in the control of acute inflammation in CVB3-infection was particularly substantiated by the finding that MHC I antigen presentation-deficient mice exert fulminant myocarditis and chronic disease.9 CD8 T cell depletion studies suggested a contribution of CD8 T cells to virus elimination in CVB3-myocarditis as well.45 Overall epitope-specific CD8 T cell quantities as shown here tend to be low in CVB3-infection in comparison with classic viral mouse models of CD8 T cell immunity like lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus or influenza virus infection. Despite similar absolute epitope-specific T cell quantities in both resistant and susceptible mice, cytokine secretion data pointed to a differential functional capacity of CD8 T cells in these mice. IFN-γ was the predominant cytokine released by epitope-specific CD8 T cells in resistant mice, whereas IL-2 secretion was pronounced by T cells from CVB3-infected A.BY/SnJ mice. Preferential IL-2 production by CD8 T cells is suggestive for a population in a proliferative state,5 thus precluding effective antiviral activity of CD8 T cells in the susceptible host at this time point. CD8 T cells in CVB3-myocarditis were shown to exert antiviral activity by the release of IFN-γ.9 Thus, the differential cytokine expression data in resistant and susceptible mice, which concur with distinctive cardiac phenotypes and viral load in these mice, suggest that epitope-specific T cells as described here may be involved in the control of CVB3-infection. IFN-γ secretion by P3D [2170-2177] specific CD8 T cells was more pronounced, which is in agreement with the preferential generation of this epitope by IPs (Figure 5, C and D) and with considerably enhanced P3D [2170-2177] -specific CD8 T cell frequencies (Figure 4A). IFN-γ levels of P3D [2170-2177]-specific T cells in C57BL/6 mice were found to be in the same magnitude as shown for hepatitis C virus- and reovirus-specific CD8 T cells.16,46 These data suggest that epitopes from the P3D region may be more effective, which is in accordance with recent findings in human beings.47

In conclusion, the present study substantiates the impact of type I IFN in the prevention of severe acute and consecutively chronic myocarditis in mice. The primary identification of CVB3 epitopes enabled novel findings with regard to the activity and function of myocardial IP in acute myocarditis. Early type I IFN responses and, consecutively, enhanced epitope generation by myocardial IP at early stages of CVB3-infection coincide with less severe disease manifestation in enterovirus myocarditis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We kindly acknowledge the superb technical assistance of Ilse Drung, Christin Keller, and Nadine Albrecht. We thank Peter Henklein for the synthesis of peptides. Also, we thank William Claycomb who generously provided HL-1 cells. We kindly appreciate discussion of the manuscript with Alice Sijts and Dietmar Zaiss.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Peter M. Kloetzel, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Institut für Biochemie CC2, Monbijoustrasse 2, D-10117 Berlin, Germany. E-mail: p-m.kloetzel@charite.de.

Supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft: SFB/TR 19 to A.V., U.K., and P.K.; SFB 421 to P.K.; and SFB/TR 19 to K.Kl. and K.Ko. The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

S.J., U.K., and G.S. contributed equally to this work.

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Mason JW. Myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy: an inflammatory link. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:5–10. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PP, Mason JW. Advances in the understanding of myocarditis. Circulation. 2001;104:1076–1082. doi: 10.1161/hc3401.095198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahrholdt H, Wagner A, Deluigi CC, Kispert E, Hager S, Meinhardt G, Vogelsberg H, Fritz P, Dippon J, Bock CT, Klingel K, Kandolf R, Sechtem U. Presentation, patterns of myocardial damage, and clinical course of viral myocarditis. Circulation. 2006;114:1581–1590. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.606509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl U, Pauschinger M, Seeberg B, Lassner D, Noutsias M, Poller W, Schultheiss HPP. Viral persistence in the myocardium is associated with progressive cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. 2005;112:1965–1970. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.548156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selinka HC, Wolde A, Sauter M, Kandolf R, Klingel K. Virus-receptor interactions of coxsackie B viruses and their putative influence on cardiotropism. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2004;193:127–131. doi: 10.1007/s00430-003-0193-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessely R, Klingel K, Santana LF, Dalton N, Hongo M, Lederer WJ, Kandolf R, Knowlton KU. Transgenic expression of replication-restricted enteroviral genomes in heart muscle induces defective excitation-contraction coupling and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1444–1453. doi: 10.1172/JCI1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingel K, Hohenadl C, Canu A, Albrecht M, Seemann M, Mall G, Kandolf R. Ongoing enterovirus-induced myocarditis is associated with persistent heart muscle infection—quantitative analysis of virus replication, tissue damage, and inflammation. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:314–318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingel K, Stephan S, Sauter M, Zell R, McManus BM, Bultmann B, Kandolf R. Pathogenesis of murine enterovirus myocarditis: virus dissemination and immune cell targets. J Virol. 1996;70:8888–8895. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8888-8895.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingel K, Schnorr JJ, Sauter M, Szalay G, Kandolf R. beta 2-microglobulin-associated regulation of interferon-gamma and virus-specific immunoglobulin G confer resistance against the development of chronic coxsackievirus myocarditis. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1709–1720. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64305-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalay G, Meiners S, Voigt A, Lauber J, Spieth C, Speer N, Sauter M, Kuckelkorn U, Zell A, Klingel K, Stangl K, Kandolf R. Ongoing coxsackievirus myocarditis is associated with increased formation and activity of myocardial immunoproteasomes. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1542–1552. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka A, Yanai H. Interferon signalling network in innate defence. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:907–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessely R, Klingel K, Knowlton KU, Kandolf R. Cardioselective infection with coxsackievirus B3 requires intact type I interferon signaling—Implications for mortality and early viral replication. Circulation. 2001;103:756–761. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.5.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deonarain R, Cerullo D, Fuse K, Liu PP, Fish EN. Protective role for interferon-beta in coxsackievirus B3 infection. Circulation. 2004;110:3540–3543. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136824.73458.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarasch N, Martin U, Kamphausen E, Zell R, Wutzler P, Henke A. Interferon-gamma-induced activation of nitric oxide-mediated antiviral activity of macrophages caused by a recombinant coxsackievirus B3. Viral Immunol. 2005;18:355–364. doi: 10.1089/vim.2005.18.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke A, Zell R, Ehrlich G, Stelzner A. Expression of immunoregulatory cytokines by recombinant coxsackievirus B3 variants confers protection against virus-caused myocarditis. J Virol. 2001;75:8187–8194. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.8187-8194.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin EC, Seifert U, Kato T, Rice CM, Feinstone SM, Kloetzel PM, Rehermann B. Virus-induced type IIFN stimulates generation of immunoproteasomes at the site of infection. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3006–3014. doi: 10.1172/JCI29832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, van den Broek M, Schwarz K, de Giuli R, Diener PA, Groettrup M. Immunoproteasomes largely replace constitutive proteasomes during an antiviral and antibacterial immune response in the liver. J Immunol. 2001;167:6859–6868. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehl B, Joeris T, Rieger M, Visekruna A, Textoris-Taube K, Kaufmann SHE, Kloetzel PM, Kuckelkorn U, Steinhoff U. Immunoproteasomes are essential for clearance of Listeria monocytogenes in nonlymphoid tissues but not for induction of bacteria-specific CD8(+) T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:6238–6244. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloetzel PM. Antigen processing by the proteasome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:179–187. doi: 10.1038/35056572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groll M, Ditzel L, Lowe J, Stock D, Bochtler M, Bartunik HD, Huber R. Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4 angstrom resolution. Nature. 1997;386:463–471. doi: 10.1038/386463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin TA, Nandi D, Cruz M, Fehling HJ, Van Kaer L, Monaco JJ, Colbert RA. Immunoproteasome assembly: cooperative incorporation of interferon gamma (IFN-gamma)-inducible subunits. J Exp Med. 1998;187:97–104. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aki M, Shimbara N, Takashina M, Akiyama K, Kagawa S, Tamura T, Tanahashi N, Yoshimura T, Tanaka K, Ichihara A. Interferon-gamma induces different subunit organizations and functional diversity of proteasomes. J Biochem. 1994;115:257–269. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers M, Boesfabian B, Ruppert T, Kloetzel PM, Koszinowski UH. The cleavage preference of the proteasome governs the yield of antigenic peptides. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1865–1870. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijts AJAM, Standera S, Toes REM, Ruppert T, Beekman NJCM, van Veelen PA, Ossendorp FA, Melief CJM, Kloetzel PM. MHC class I antigen processing of an Adenovirus CTL epitope is linked to the levels of immunoproteasomes in infected cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:4500–4506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijts AJAM, Ruppert T, Rehermann B, Schmidt M, Koszinowski U, Kloetzel PM. Efficient generation of a hepatitis B virus cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope requires the structural features of immunoproteasomes. J Exp Med. 2000;191:503–513. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hall T, Sijts A, Camps M, Offringa R, Melief C, Kloetzel PM, Ossendorp F. Differential influence on cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope presentation by controlled expression of either proteasome immunosubunits or PA28. J Exp Med. 2000;192:483–494. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz K, van den Broek M, Kostka S, Kraft R, Soza A, Schmidtke G, Kloetzel PM, Groettrup M. Overexpression of the proteasome subunits LMP2. LMP7, and MECL-1, but not PA28 alpha/beta, enhances the presentation of an immunodominant lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus T cell epitope. J Immunol. 2000;165:768–778. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young GW, Wang YJ, Ping PP. Understanding proteasome assembly and regulation: importance to cardiovascular medicine. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandolf R, Hofschneider PH. Molecular cloning of the genome of a cardiotropic coxsackie-b3 virus—full-length reverse-transcribed recombinant cDNA generates infectious virus in mammalian cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4818–4822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.14.4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuckelkorn U, Ruppert T, Strehl B, Jungblut PR, Zimny-Arndt U, Lamer S, Prinz I, Drung I, Kloetzel PM, Kaufmann SHE, Steinhoff U. Link between organ-specific antigen processing by 20S proteasomes and CD8(+) T cell-mediated autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2002;195:983–990. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claycomb WC, Lanson NA, Stallworth BS, Egeland DB, Delcarpio JB, Bahinski A, Izzo NJ. HL-1 cells: a cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2979–2984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang C, Sauter M, Szalay G, Racchi G, Grassi G, Rainaldi G, Mercatanti A, Lang F, Kandolf R, Klingel K. Connective tissue growth factor: a crucial cytokine-mediating cardiac fibrosis in ongoing enterovirus myocarditis. J Mol Med-Jmm. 2008;86:49–60. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuckelkorn U, Ferreira EA, Drung I, Liewer U, Kloetzel PM, Theobald M. The effect of the interferon-gamma-inducible processing machinery on the generation of a naturally tumor-associated human cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope within a wild-type and mutant p53 sequence context. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1368–1375. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200205)32:5<1368::AID-IMMU1368>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalay G, Sauter M, Hald J, Weinzierl A, Kandolf R, Klingel K. Sustained nitric oxide synthesis contributes to immunopathology in ongoing myocarditis attributable to interleukin-10 disorders. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:2085–2093. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammensee HG, Bachmann J, Emmerich NPN, Bachor OA, Stevanovic S. SYFPEITHI: database for MHC ligands and peptide motifs. Immunogenetics. 1999;50:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s002510050595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandolf R, Canu A, Hofschneider PH. Coxsackie B3-virus can replicate in cultured human fetal heart cells and is inhibited by interferon. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1985;17:167–181. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(85)80019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller U, Steinhoff U, Reis LFL, Hemmi S, Pavlovic J, Zinkernagel RM, Aguet M. Functional role of type-I and type-I interferons in antiviral defense. Science. 1994;264:1918–1921. doi: 10.1126/science.8009221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Hendriks W, Althage A, Hemmi S, Bluethmann H, Kamijo R, Vilcek J, Zinkernagel RM, Aguet M. Immune response in mice that lack the interferon-gamma receptor. Science. 1993;259:1742–1745. doi: 10.1126/science.8456301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj NBK, Cheung SC, Rosztoczy I, Pitha PM. Mouse genotype affects inducible expression of cytokine genes. J Immunol. 1992;148:1934–1940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber S, Sartini D, Exley M. Role of CD1d in coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis. J Immunol. 2003;170:3147–3153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deol P, Zaiss DMW, Monaco JJ, Sijts AJAM. Rates of processing determine the immunogenicity of immunoproteasome-generated epitopes. J Immunol. 2007;178:7557–7562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Princiotta MF, Finzi D, Qian SB, Gibbs J, Schuchmann S, Buttgereit F, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Quantitating protein synthesis, degradation, and endogenous antigen processing. Immunity. 2003;18:343–354. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell CT, Kiosses WB, Harkins S, Whitton JL. Inhibition of protein trafficking by coxsackievirus B3: multiple viral proteins target a single organelle. J Virol. 2006;80:6637–6647. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02572-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell CT, Mosses WB, Harkins S, Whitton L. Coxsackievirus B3 proteins directionally complement each other to downregulate surface major histocompatibility complex class I. J Virol. 2007;81:6785–6797. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00198-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke A, Huber S, Stelzner A, Whitton JL. The role of Cd8(+) T-lymphocytes in coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis. J Virol. 1995;69:6720–6728. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6720-6728.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prestwich RJ, Errington F, Ilett EJ, Morgan RSM, Scott KJ, Kottke T, Thompson J, Morrison EE, Harrington KJ, Pandha HS, Selby PJ, Vile RG, Melcher AA. Tumor Infection by oncolytic reovirus primes adaptive antitumor immunity. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7358–7366. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinzierl AO, Rudolf D, Maurer D, Wernet D, Rarnmensee HG, Stevanovic S, Klingel K. Identification of HLA-A*01-and HLA-A*02-restricted CD8(+) T-cell epitopes shared among group B enteroviruses. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:2090–2097. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/000711-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.