Abstract

Murine neurocysticercosis is a parasitic infection transmitted through the direct ingestion of Taenia solium eggs, which differentially disrupts the barriers that protect the microenvironment of the central nervous system. Among the host factors that are involved in this response, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) have been recently described as important players. Doxycycline is a commonly prescribed antimicrobial drug that acts as an anti-inflammatory agent with broad inhibitory properties against MMPs. In this study, we examined the effects of doxycycline treatment in a murine model of neurocysticercosis. Animals treated with doxycycline exhibited reduced morbidity and mortality throughout the course of infection. Although similar levels of leukocyte infiltration were observed with both treatment regimens, doxycycline appeared to provide improved conditions for host survival, as reduced levels of apoptosis were detected among infiltrates as well as in neurons. As an established MMP blocker, doxycycline reduced the degradation of junctional complex proteins in parenchymal vessels. In addition, doxycycline treatment was associated with an overall reduction in the expression and activity of MMPs, particularly in areas of leukocyte infiltration. These results indicate that a broad-range inhibitor of MMPs promotes host survival and suggest the potential of doxycycline as a therapeutic agent for the control of inflammatory responses associated with neurocysticercosis.

Neurocysticercosis (NCC) is a parasitic infection of the central nervous system (CNS) that accounts for approximately one-third of all seizure and epilepsy cases in most developing countries.1,2,3 Transmission of NCC occurs due to direct ingestion of Taenia solium eggs through the fecal-enteric route.4 On ingestion, the eggs undergo peptic digestion, releasing oncospheres that traverse the intestinal wall and enter the blood stream. The oncospheres are then transported to distinct tissues, preferentially to the CNS where they develop into cysts.5,6

The clinical manifestations of NCC largely depend on the number, type, size, location, and developmental stage of the cysticerci, in addition to the extent of the host immune response.5,6,7 Live cysticerci can persist in the CNS for long periods of time without causing symptoms, largely by immune evasion and suppression mechanisms associated with the organism.8 As the parasite dies, these regulatory mechanisms are lost, and a strong inflammatory response is induced, precipitating the development of symptoms.9 The earlier stages of this response are characterized by infiltration of leukocytes preferentially displaying a Th1 immune profile.10 Later, granuloma formation associated with fibrosis, angiogenesis, and a mixed Th1/Th2 response is detected.11

Inflammatory responses in the CNS are generally characterized by disruption of the CNS barriers.12 The CNS barriers, which include the blood brain barrier (BBB) and the blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier, are functionally involved in restricting the movement of leukocytes and immune mediators from the bloodstream to the CNS.13 Studies in the murine model of NCC indicate that there is a differential breakdown of the BBB and blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier that correlates with distinct expression patterns of MMPs.14,15 MMPs are zinc-dependent endopeptidases involved in tissue remodeling by controlling the turnover of extracellular matrix components during homeostasic, developmental, and pathological processes.16,17,18 MMP activity in the CNS is relatively low under homeostatic conditions. However, on brain injury uncontrolled expression of MMPs results in inflammation and cell death.19 In murine NCC, leukocytes appear to be the main source of MMPs, although detection of MMP activity has also been observed in astrocytes, microglia, ependyma, and the choroid plexus.15,20 Under pathological conditions, MMP activity mediates disruption of CNS barriers by degrading junctional complex proteins and extracellular matrix components associated with endothelial cells, astrocytic processes, and meninges.15,20,21,22,23,24

While a wide array of drugs has been used as MMP inhibitors, compounds belonging to the family of tetracyclines, such as doxycycline and minocycline have been used more commonly in clinical studies because of their anti-inflammatory effects, antimicrobial action, and well-characterized clinical safety profile.25,26 Various studies have shown that doxycycline reduces inflammation by acting as a broad spectrum, competitive, and nonspecific MMP blocker.27 In the CNS, doxycycline is known to be rapidly absorbed, showing good penetration into the parenchyma and ventricles.28 Research using experimental models has shown that doxycycline improves survival in a rat model of pneumococcal meningitis and also reduces the BBB damage in a rat model of cerebral ischemia.26,29

Our laboratory has developed a murine model of NCC using the metacestode form of the parasite Mesocestoides corti, which is highly related to T. solium.30 In murine NCC, the expression and activity of several MMPs have been detected in multiple anatomical areas that support entry of leukocytes and inflammatory mediators into the CNS.15 Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of doxycycline, an inhibitor of MMPs on the outcome of murine NCC. It was found that doxycycline significantly reduces morbidity and mortality in mice infected with M. corti, and the improved outcome was associated with an overall reduction in apoptosis, evidence of oxidative stress, and MMP activity in areas of major leukocyte infiltration.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Female BALB/c mice, 3 to 5 weeks old, were purchased from the National Cancer Institute Animal Program (Bethesda, MD). Animal experiments were conducted under the guidelines of the University of Texas System, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the National Institutes of Health. Animals were sacrificed at 1 week, 3 weeks, and 5 weeks after inoculation and analyzed for parasite burden, immune cell infiltration, apoptosis, oxidative stress, junctional complex proteins, and MMP expression/activity. Before sacrifice, animals were anesthetized with 80 μl of anesthetic cocktail containing 100 mg/ml ketamine and 4 mg/ml xylazine mixture (Laboratory Animal Resource, University of Texas at San Antonio, TX). The right atrium was punctured, and the heart left ventricle was perfused with 15 ml of cold PBS. Three to five animals were analyzed for each postinfection time with multiple sections analyzed per animal.

Parasites and Inoculations

Mesocestoides corti metacestodes were maintained by serial intraperitoneal inoculation of 8- to 12-week-old female BALB/c mice. For the intracranial infection, metacestodes were harvested aseptically from the peritoneal cavity and washed thoroughly with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS). An inoculum of 50 parasites suspended in 50 μl of HBSS was injected intracranially using a 1-ml tuberculin syringe with a 25-gauge needle.30 Before intracranial inoculation, mice were anesthetized intramuscularly with 80 μl of anesthetic cocktail. For the intracranial inoculation, the needle was inserted 2 mm deep into the bregma region where there is space between the skull and the brain tissue.30 This ensures that the needle does not penetrate the nervous tissue. Control mice were injected intracranially with 50 μl of HBSS.

Doxycycline Treatment

Doxycycline was dissolved in HBSS and administered at a dose of 50 mg/kg/animal in 50 μl. Mice were injected intraperitoneally 1 day before infection and every day afterward during the first week of infection. After the first week, animals were injected intraperitoneally with 30 mg/kg/animal in 50 μl every other day until completion of the experiment. This dose has been previously shown to inhibit MMP activity in the CNS of rodents.29,31 Control-infected mice (sham) were injected with 50 μl of HBSS at the same time points. Mock-infected mice injected with or without doxycycline were also analyzed.

Tissue Processing

For sectioning, perfused brains were immediately removed, embedded in optimal cutting temperature resin (Sakura, Torrance, CA) and frozen quickly in dry ice. Serial horizontal sections of 9 μm were taken at a working temperature of −20°C and mounted on Prep slides (Sigma Biosciences, St. Louis, MO). One in every five slides was fixed in formalin for 10 minutes at room temperature and stained with H&E. The remainder of the slides was air dried overnight and fixed in fresh acetone for 20 seconds at room temperature. Acetone-fixed sections were wrapped in aluminum foil and stored at −80°C or processed immediately for immunofluorescence (IF).

H&E Staining and Analysis

Formalin-fixed sections were dehydrated by washing with 100% ethanol for 30 seconds and rehydrated with deionized water. The slides were treated with hematoxylin for 30 seconds, followed by water wash, and eosin for 10 seconds. Next, the slides were washed with 95% and 100% ethanol for 1 and 1.5 minutes each. Before mounting, the sections were immersed in xylene twice for 2.5 minutes each time. Finally, mounting was done with Cytoseal (Richard-Allan Scientific, MI). H&E images were acquired using a Leica DMR microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar Germany) and a cooled CCD SPOT RT camera (Diagnostic Instruments Inc, Sterling Heights, MI). The entire brain was serially cryosectioned to determine the number of parasites (n = 6/group/time point). The number of perivascular leukocytes in parenchymal postcapillary venules (n = 12) were obtained from H&E stained serial sections from three animals per treatment in the fifth week of infection.

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyltransferase-Mediated dUTP Nick-End Labeling Assay

The terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay was performed using the ApopTag plus fluorescence in situ apoptosis detection kit (Chemicon International, CA). DNA strand breaks were detected by enzymatic labeling of the free 3′-OH termini. The labeling involved fixing the slides in 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 seconds at room temperature. The slides were then washed with PBS twice followed by a 10-second incubation with equilibrium buffer. Working strength TdT diluted in reaction buffer was then added and incubated for 40 minutes at 37°C. For the negative control, reaction buffer alone was added. The slides were then washed in stop/wash buffer with agitation for 15 seconds, followed by a 10-minute incubation. The slides were then washed twice in PBS and incubated with anti-digoxigenin conjugated with fluorescein in blocking buffer for 30 minutes followed by washing with PBS. The sections were then mounted using fluorsave reagent (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) containing 0.3 μmol/L 4′, 6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dilactate (DAPI, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). After TUNEL staining some sections were immunostained with the Neuron specific nuclear protein (NeuN) antibody to establish the identity of the cortical cells displaying apoptosis. Immunostaining was performed as described in the IF microscopy section.

Antibodies

Antibodies purchased from Triple Point Biologics (Forest Grove, OR) were all produced in rabbits and included anti-stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) carboxyterminal end, anti-macrophage elastase (MMP-12) carboxyterminal end, and anti-membrane-type MMP-3 (MT3-MMP, MMP-16) hinge region. Antibodies purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MI) were also raised in rabbits and include anti-gelatinase A (MMP-2) hinge region, anti-collagenase 2 (MMP-8) hinge region and anti-gelatinase B (MMP-9). Rat anti-CD11b phycoerythrin-conjugated, rat anti-mouse Gr1 Alexa 488-cojugated, anti-mouse αβ T cell receptor phycoerythrin-conjugated, purified rat anti-interleukin (IL)-6, and purified rat anti-vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin were purchased from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Rabbit anti-mouse claudin-3 was purchased from Zymed (San Francisco, CA). The purified goat anti-junctional adhesion molecule A and purified goat anti-vascular endothelial growth factor were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Rat anti-zonula occludens 1 antibody was purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). Rabbit anti-metallothionein (MT) was purchased from AbD Serotec (Oxford, UK). Mouse anti-NeuN biotinylated was purchased from US Biological (Swampscott, MA) Rabbit primary antibodies were detected with a rhodamine red X-conjugated AffiniPure donkey anti-rabbit IgG, and rat antibodies with a rhodamine red X- and Cy2-conjugated AffiniPure anti-rat IgG purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). Goat primary antibodies were detected with an Alexa 488-conjugated anti-goat IgG from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). All antibodies were titrated with brain sections from mock-infected and 2-week infected animals to determine optimal concentrations before use.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Double IF staining was performed as previously described.14 Slides containing the brain sections were thawed for 30 minutes at room temperature. The slides were then fixed in acetone for 10 minutes and 70% ethanol for 5 minutes at −20°C. Sections were then rehydrated with PBS for 3 minutes and washed with a Tris-NaCl-Tween 20 buffer. Nonspecific immunoglobulin binding was prevented by blocking the sections with 10% serum from the same species in which the fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies were generated. Sections were then incubated with titrated concentrations of the primary antibody for 45 minutes in a humid chamber and washed with Tris-NaCl-Tween 20 seven times, with 3 minutes between washes. A secondary antibody was added if the primary antibody was not already conjugated with a fluorochrome and incubated for 30 minutes in a humid chamber followed by washes. Where indicated, a second pair of primary and secondary antibodies was incubated. Negative controls using secondary antibodies alone were used in each experiment and found to be negative for staining. After washing, sections were mounted using Fluorsave reagent (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) containing DAPI (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Fluorescence was visualized using a Leica DMR epifluorescent microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar Germany). Images were acquired using a cooled CCD SPOT RT camera (Diagnostic instruments Inc, Sterling Heights, MI). For image analysis, the same parameters were used when acquiring images to allow direct comparison of pixel intensity.

In Situ Zymography

In situ zymography was used to detect and localize gelatinolytic and collagenolytic activity in brain tissue and it was performed as previously described.15 Briefly, sections were fixed and hydrated for IF analyses. A solution containing DQ-gelatin or collagen (Molecular probes, Eugene, OR) labeled with fluorescein and Oregon 488 respectively, were used to determine activity of MMPs in situ. Sections were incubated 40 minutes at room temperature with 1 μg/ml of DQ-gelatin in reaction buffer (0.05 M/L Tris-HCl, 0.15 M/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L CaCl2, pH 7.6) or with 5 mg/ml of collagen-oregon 488 in PBS, and then washed with Tris-NaCl-Tween 20 buffer. In situ zymography was followed by IF to correlate the levels of active and inactive MMPs in the sections. Negative controls included pre-incubation with the MMP inhibitor 1, 10-phenanthroline (10 mmol/L) and EDTA (10 mmol/L). Images were acquired, processed and analyzed as described for IF.

Imaging Processing and Analysis

The images were processed using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe, Mountain View, CA). The intensity of staining in each of the sections was analyzed by measuring pixel intensity using IP Lab software (BD Biosciences Bioimaging, Rockville MD). A total of five to ten readings were recorded from each of the treatments at each postinfection time and areas of staining such as astrocytic processes, neurons, infiltrating cells, and interendothelial junction proteins, were selected as regions of interest for pixel intensity analysis. A total of 10 readings were taken and the average pixel intensity in the regions of interest was calculated for comparison among experimental treatments.

Statistical Analysis

The differences in pixel intensity, parasite numbers, and number of infiltrating cells were evaluated with a Student’s t-test using Sigma Plot software (Systat Software, San Jose CA) where a P value <0.05 was considered a significant change. Survival of mice was analyzed with the log rank test using Medcalc software (Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

Doxycycline Treatment Reduces Morbidity and Mortality in Murine NCC

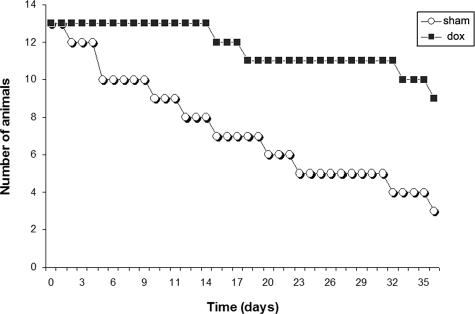

To determine whether doxycycline affects disease progression in murine NCC, animals were started on treatment with doxycycline 1 day before M. corti infection together with sham controls. It was found that sham animals showed a more rapid progression in the worsening of the disease when compared with doxycycline-treated animals. Mild piloerection, lethargy, and unstable gait were observed 1 week postinfection (WPI) in the sham animals, followed by tilted head, marked weight loss, loss of fur, repetitive walking in circles, and death, as the infection progressed. In contrast, doxycycline-treated animals showed no overt disease symptoms during the first 2 weeks of infection. After 3 weeks, some animals exhibited mild piloerection and lethargy. The health of the animals deteriorated in the subsequent weeks, but to a lesser extent when compare to sham mice (see supplementary Video 1 and 2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Doxycycline treatment resulted in a significant increase in survival rate in murine NCC (Figure 1). We also evaluated the health status of mock-infected animals treated or not treated with doxycycline. There were no apparent signs of disease or mortality in either group.

Figure 1.

Effect of doxycycline on survival of M. corti infected mice. Survival period of sham-treated (circles) and doxycycline (dox)-treated mice (squares) n = 13. The survival of sham mice was significantly (P value <0.0001) different from those treated with dox according to the Log rank test.

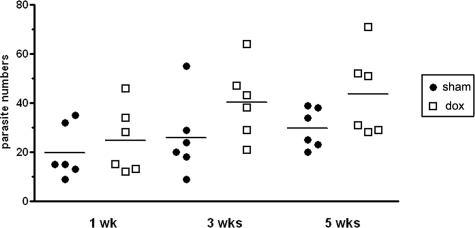

Effect of Doxycycline in Number of Parasites

To determine the effect of doxycycline on the number of parasites, entire brains were sectioned and stained with H&E to count the number of parasites. Although there was a trend toward reduced numbers of parasites in the doxycycline-treated animals, no significant differences were found when both treatments were compared (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Total number of parasites in sham and doxycycline treated mice. Animals were intracranially inoculated with M. corti and at the indicated times were sacrificed and processed for H&E staining (n = 6). There are no significant differences in the number of parasites detected in both treatments.

Distribution and Characterization of Infiltrates during Doxycycline Treatment

Murine NCC is characterized by differential migration of immune cells according to the anatomical area analyzed.14 To determine whether the reduced morbidity and mortality found in doxycycline-treated animals is due to changes in the level of immune cell infiltration, histological and IF analyses were performed. Leptomeninges are the anatomical areas within the brain with the highest levels of immune cell infiltration in murine NCC.14 H&E staining revealed that throughout the course of infection these areas presented similar levels of immune cell infiltration in both sham (Figure 3A) and doxycycline-treated infected mice (Figure 3B). Infiltrates in sham animals showed cell body asymmetry, apparent cell shrinkage, and chromatin condensation, suggesting that many of these cells are undergoing apoptosis (Inset Figure 3A). On the contrary, immune infiltrates in doxycycline-treated animals tended to exhibit a larger cytoplasm and loosely clumped chromatin, and in general, had a healthier appearance (Inset Figure 3B). As observed previously,14 the level of infiltration in the parenchyma was considerably lower when compared with leptomeninges (Figure 3). However, the extent of leukocyte infiltration into the parenchyma of drug-treated animals was significantly lower than in sham mice (Figure 3, C–E).

Figure 3.

Leukocyte infiltration in sham and doxycycline-treated mice. Representative images of leukocyte distribution assessed in H&E-stained slides of doxycycline (dox) and sham mouse brain at different times postinfection. The magnification in all images is ×40. A: Leukocyte infiltration around pial vessels (asterisks) 3 WPI. Inset shows a magnified image (×2) of infiltrates exhibiting dark blue staining in nuclei, cell body asymmetry, and apparent cell shrinkage. B: Pial vessels (asterisks) with perivascular infiltrates, 3 WPI. Inset shows a magnified image (×2) where larger cytoplasm and loosely clumped chromatin are evident in infiltrating cells. C: Perivascular infiltration in parenchymal vessel (asterisk) 5 WPI. D: Moderate infiltration around parenchymal vessel (asterisk) 5 WPI. E: Number of perivascular leukocytes in parenchymal vessels (n = 12) of sham and dox mice 5 WPI. The data obtained was compared using a Student’s t-test. Error bar = SEM. **P < 0.01.

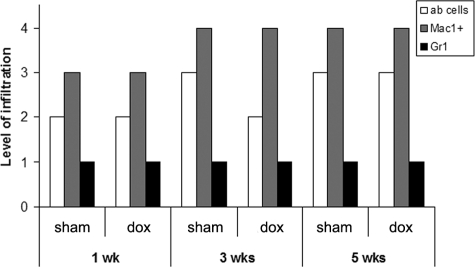

To determine whether doxycycline had an effect on the phenotype of immune cells infiltrating the brain we analyzed the kinetics and number of leukocyte subsets accumulating in leptomeninges and parenchymal vessels. Doxycycline does not affect the number of macrophages and αβ T cells infiltrating the brain as high numbers of these cells were detected in both experimental groups at the different postinfection times tested (Figure 4). Similarly, moderate infiltration of granulocytes has been described in murine NCC14 and comparable numbers of these cells were found in the presence and absence of drug (Figure 4). Despite the lower level of immune cell infiltration around parenchymal vessels in doxycycline-treated mice, the leukocyte subsets in these areas were comparable between both groups (data not shown). Finally, there were no apparent differences in the number of leukocytes present in mock sham or mock doxycycline-treated animals; leukocytes were barely detectable in either group (data not shown,14). Taken together, these observations indicate that doxycycline does not substantially affect the number or subsets of leukocytes that infiltrate during murine NCC.

Figure 4.

Kinetics of leukocyte infiltration in internal leptomeninges of sham and doxycycline treated mice. Characterization of cellular infiltrates was done using the antibodies described in Materials and Methods. Mice were intracranially inoculated with M. corti and at the indicated times were sacrificed and processed for IF analysis. n = 3 per infection time and per treatment. The relative level of leukocyte infiltration after infection with M. corti was arbitrarily assigned a score and represent: 0 (null) to 4 (abundant).

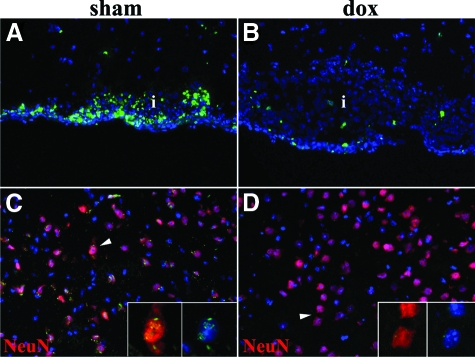

Doxycycline Reduces the Extent of Apoptosis in Infected Brain Tissue

The level of immune cell infiltration was comparable in both treatments, although some of the leukocytes from sham animals showed fragmented nuclei, nuclear chromatin condensation, and dark staining in the cytoplasm, suggesting that apoptosis was taking place in these cells. To further analyze this observation, the TUNEL assay was performed in brain sections of sham and doxycycline-treated animals at 1, 3, and 5 WPI. Apoptosis was high among immune infiltrates in the sham mice, especially in leptomeningeal areas (Figure 5A) and infiltrates surrounding the parasite. In contrast, there was a much lower degree of apoptosis in the anatomical areas displaying high levels of immune infiltration in doxycycline-treated animals (Figure 5B). TUNEL analysis of parenchymal areas showed cortical neurons (NeuN+) displaying moderate levels of apoptosis in sham animals (Figure 5C), while analysis of comparable areas in the doxycycline-treated animals showed very low or no apoptosis (Figure 5D). In summary, the level of apoptosis in immune infiltrates and neurons was lowered by doxycycline treatment at the postinfection times analyzed.

Figure 5.

Detection of apoptosis using TUNEL staining in sham- and doxycycline-treated mice. The magnification in all images is ×40. A: Abundant TUNEL staining in leptomeningeal infiltrate (i) 1 WPI. B: Scarce TUNEL staining in leptomeningeal infiltrate of doxycycline (dox) treated mouse. 1 WPI. C: Neurons (NeuN+) displayed moderate tunel staining in the cortex. 5 WPI. D: Very low to absent apoptosis in cortical neurons (NeuN+) of dox-treated mouse. 5 WPI.

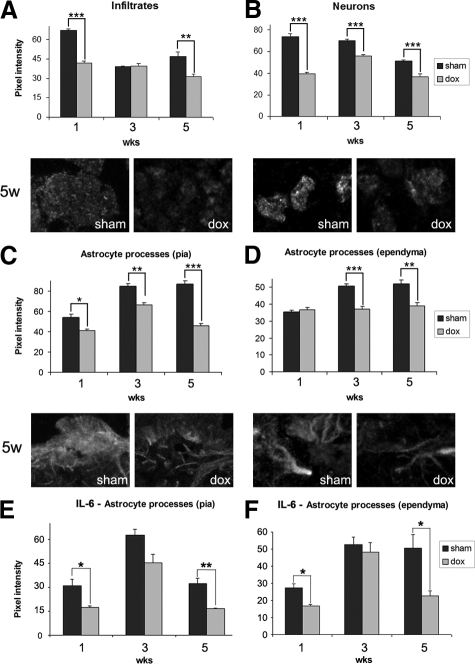

Increased levels of apoptosis are commonly associated with high levels of oxidative stress.32 To analyze the extent of oxidative stress, the expression of metallothioneins (MTs) was determined in the presence or absence of drug by IF microscopy and measurement of pixel intensity. MTs are factors known to reduce oxidative stress and apoptosis during various CNS disorders.33,34 MTs were detected in infiltrating cells, neurons, and astrocytic processes. Analysis of multiple postinfection times showed that doxycycline treatment resulted in decreased expression of MTs in leptomeningeal infiltrates at 1 and 5 WPI (Figure 6A). Neurons also exhibited a reduced expression of MTs with doxycycline treatment, as compared with sham, including the 3-week time point (Figure 6B). Expression of MTs in astrocytic processes opposing the pia progressively increased, and it was significantly higher in sham than doxycycline treated mice (Figure 6C). Although the levels of MTs were lower in astrocytic processes juxtaposing ependyma, doxycycline treatment significantly decreased expression of MTs (Figure 6D). As IL-6 is a major inducer of MTs35 and it is expressed by astrocytes in murine NCC,14 we analyzed the effect of doxycycline on its expression by astrocytes. It was found that doxycycline treatment lowered the levels of IL-6 expression in astrocytic processes opposing the pia (Figure 6E), which correlated with the reduced pattern of expression detected for MTs (Figure 6C). Doxycycline also lowered the overall expression of IL-6 in the astrocytic processes opposing ependyma at 1 and 5 WPI (Figure 6F). Finally, no MT expression was detected in the astrocytic processes surrounding parenchymal vessels in the presence or absence of drug.

Figure 6.

Changes in the levels of methallothionein (MT) and IL-6 expression on doxycycline treatment. IF based determination supported by pixel intensity analysis was done for MTs in (A) internal leptomeninges infiltrates, (B) neurons, (C) astrocytic processes opposing the pia, and (D) astrocytic processes opposing ependyma. Pixel intensity analysis of IL-6 expression was done in (E) astrocytic processes opposing the pia and (F) astrocytic processes juxtaposing the ependyma. MT and IL-6 expression was compared between sham (dark bars) and doxycycline (dox) (gray bars) treated mice 1, 3, and 5 WPI. The data obtained were compared using a Student’s t-test where differences are *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.005. Error bar = SEM. Representative images of MT expression 5 WPI are included for each cell/structure analyzed.

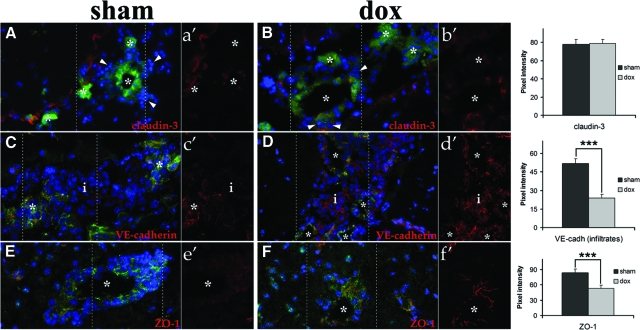

Extent of CNS Barrier Disruption in Doxycycline-Treated Animals

To determine the effect of doxycycline on BBB disruption, the expression of junctional complex proteins was examined in infected animals with and without drug. The tight junction (TJ) proteins ZO-1, claudin-3, and junctional adhesion molecule A in addition to the adherens junction protein VE-cadherin were analyzed. junctional adhesion molecule A was used to label the CNS vessels as the expression of this TJ protein is not lost during the course of murine NCC.20 The extent and timing of BBB disruption in pial vessels was similar in the presence or absence of drug. Analyses of multiple infection times showed a progressive loss of the structured association of junctional proteins at interendothelial connections in pial vessels of doxycycline- and sham-treated animals. The TJ proteins appeared shorter, thicker, and in some instances were undetected in portions of the vessels in the presence or absence of drug (Figure 7, A–B). Such changes in the appearance of these proteins were associated with leukocyte extravasation (Figures 4 and 7, A–B) and correlate with the breakdown of the BBB previously reported.20 Analysis of adherens junction protein VE-cadherin showed the same time-dependent architectural changes depicted for TJ proteins with no apparent differences in the two experimental groups (Figure 7, C–D). Interestingly, VE-cadherin was found in the leukocyte-infiltrating leptomeninges with a significantly higher expression in immune cells of doxycycline-treated mice (Figure 7, C–D). Disruption of the tight junctional architecture was observed in some parenchymal vessels at 5 WPI, but in contrast to pial vessels, the changes in architecture and loss of junctional complex proteins as zonula occludens 1 were more significant in sham animals (Figure 7E) than in those treated with doxycycline (Figure 7F). These results correlate with the lower number of leukocytes detected in the periphery of parenchymal vessels (Figure 3E).

Figure 7.

Expression of the anatomical components of CNS barriers in sham and doxycycline treated mice. Junctional adhesion molecule A is represented in green (Alexa 488) and the other junctional complex proteins are red (Rhodamine red X). For each picture a section (between dashed lines and labeled a′, b′, etc) only showing the junctional complex protein shown in red was included to better appreciate changes in expression. Blue represents the nuclei stained with DAPI. Pictures A–D were taken with a ×40 objective, E and F were taken with a ×60 objective. A-B: Disruption and partial loss of claudin-3 (a′–b′) expression in pial vessels (asterisks) 3 WPI. Arrowheads indicate cells infiltrating leptomeninges. C-D: Disruption and partial loss of VE-cadherin (c′–d′) in junctional complexes of pial vessels (asterisks) 3 WPI. VE-cadherin (c′–d′) was detected in infiltrates (i), with higher expression found in dox (d′). E–F: Parenchymal vessels (asterisk) expressing ZO-1 (e′–f′), higher degree of disruption was detected in sham (e′) 5 WPI. Pixel intensity analysis of claudin-3 expression in TJs (A–B), VE-cadherin in infiltrates (C–D), and ZO-1 in parenchymal vessels TJs (E–F) is included. The data obtained were compared using a Student’s t-test. Error bar = SEM. ***P < 0.005.

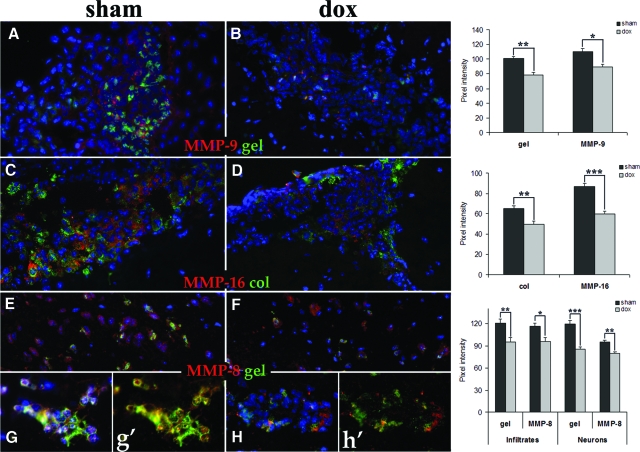

Effect of Doxycycline Treatment on MMP Activity

As doxycycline treatment reduced the level of apoptosis and oxidative stress in the distinct anatomical areas examined and partially diminished the infiltration of immune cells in parenchymal areas, we next analyzed the expression of MMPs. MMPs are multifunctional enzymes known to play an important role in modulating the permeability of CNS barriers36 and regulating the apoptotic process.37 The expression and activity of MMPs at the protein level was evaluated in leptomeningeal and parenchymal areas. Most of the cells migrating into the CNS access through pial vessels located in leptomeninges. Such infiltrates in sham animals displayed a significant increase in the expression of MMPs 9 (Figure 8A), 8, 16 (Figure 8C), 12, and 3, when compared with those in doxycycline treated mice (Figure 8, B–D). Doxycycline also significantly reduced MMP activity, as gelatin (Figure 8B) and collagen (Figure 8D) degradation was lower in leukocytes infiltrating leptomeninges. Previous studies in animals infected with M. corti have demonstrated constitutive expression of MMPs 2, 3, 8, 9, and 12 in neurons and glial cells (unpublished observations). In this study, analysis of cortical areas confirmed the expression of these MMPs in nervous tissue cells of sham mice with some of the cells expressing the active form of the enzyme as gelatin degradation was detected (Figure 8E). In contrast, expression and activity of MMPs in cortical areas was significantly reduced in animals treated with doxycycline (Figure 8F). Such reduction was also evident in leukocytes extravasating parenchymal vessels late in the infection (Figure 8H), when compared with those in the sham group (Figure 8G). In addition, reduced MMP expression was associated with diminished MMP activity (Figure 8H). In summary, the overall expression and activity of MMPs in infiltrating leukocytes and cortical nervous tissue cells was partially abrogated by the doxycycline treatment in the brains of M. corti infected mice.

Figure 8.

Effect of doxycycline treatment in expression and activity of MMPs at distinct anatomical compartments of brain infected with M. corti. In situ zymography with gel and col (green) as substrates and IF with polyclonal antibodies against distinct MMPs (red) were used to compare the expression and activity of MMPs in sham (left panels) and dox (right panels) treated animals. Blue represents the nuclei stained with DAPI. The original magnification in all images is ×40; images G and H are magnified ×2. A–B: MMP-9 expression and gelatinolysis in leptomeningeal infiltrates 3 WPI. C–D: Expression and activity of MMP-16 in leptomeningeal infiltrates 3 WPI. E–F: MMP-8 expression and gelatinolysis in cortical areas 3 WPI. G–H: Expression and activity of MMP-8 in leukocytes infiltrating from parenchymal vessels 5 WPI. In images g′ and h′ the DAPI staining was not included to better visualize the differences in MMP-8 expression and activity after DOX treatment. Pixel intensity analysis of MMP-9 expression and gelatinolysis (A–B), MMP-16 and collagenolysis (C–D), and MMP-9 expression/gelatinolysis in cortex and perivascular infiltrates (E–H) is included. The data obtained were compared using a Student’s t-test. Error bar = SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005.

Discussion

During murine NCC, the migration of leukocytes into the brain involves the differential disruption of the multiple CNS barriers and depends on the expression and activity of various MMPs.14,15,20,22 This study was designed to examine the effect of a broad range MMP inhibitor on leukocyte infiltration into the CNS and the outcome of infection in a well established model of NCC. Our data show that doxycycline treatment significantly reduces the symptomatology and mortality rate during the course of parasitic infection. Although differences in the level of leukocyte infiltration were expected, there were no striking differences in the number or immune cell types infiltrating the brain in the presence or absence of the drug. Instead, the beneficial effect of the inhibitor was associated with reduction of apoptosis, MMP activity, evidence of oxidative stress, and the extent of pathology.

Murine NCC is characterized by an exaggerated immune response that is due in part to the large infiltration of macrophages, dendritic cells, and T cells into the CNS.14,30 Since the expression and activity of MMPs have been associated with breakdown of the CNS barriers and infiltration of leukocytes into the brain,15 it was hypothesized that a broad range inhibitor of MMPs like doxycycline could reduce barrier disruption and leukocyte influx, and hence decrease disease severity. However, despite the reduced disease severity, the level of extravasation and phenotype of the immune cells was not substantially different in major areas of infiltration when both groups were compared. Nonetheless, many of the leukocytes infiltrating the brain of the sham mice showed morphological features suggestive of apoptosis. On further examination, the level of apoptosis was higher in infiltrates as well as in cortical areas of sham mice than those treated with drug. Reduction in the overall cell death within the CNS should have a positive impact in the course of the infection by diminishing the inflammatory process. Doxycycline is known to reduce the susceptibility of cells to pro-apoptotic insult by restricting the release of cytochrome c and the activation of caspases 3 and 9.38 In addition, MMP inhibition in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia resulted in lower levels of apoptosis and decreased morbidity. This protection was associated with a reduction of cytochrome c release and α-spectrin proteolysis.39 Finally, the survival of CNS cells and particularly neurons in our model may be dependent on the cell–matrix interactions controlled by the PI3-kinase-Akt cascades. Cessation of these signaling pathways can trigger apoptosis as a result of the MMP-driven loss of cell–matrix homeostasis.40,41

In various CNS disorders, apoptosis is known to be initiated by oxidative stress.33,34,42 MTs are among the various molecules known to respond to conditions involving oxidative stress in the CNS by chelating free radicals and metal ions.43 Although MTs are present throughout the brain, they are primarily expressed in astrocytes and to a lesser extent in ependymal cells, blood vessels, pia mater, and epithelial cells of the choroid plexus.44,45,46,47 During murine NCC, MTs were detected in astrocytes and neurons, but also in inflammatory infiltrates. The expression of MTs was reduced in doxycycline-treated mice, suggesting lower levels of oxidative stress and consistent with the decreased levels of apoptosis in drug-treated animals. In addition, the increased levels of MTs and IL-6 in astrocytic processes of sham-infected animals correlate with the high degree of hypertrophia seen in astrocytic processes opposing pia and ependyma in this model.14 Thus, we show that the anti-inflammatory and MMP inhibitory properties of doxycycline correlate with the reduced levels of apoptosis and oxidative stress found in this study.

The level of leukocyte infiltration is associated with the extent of junctional complex damage and directly reflects the integrity of the CNS barriers.20,22 As the level of infiltration is mostly similar between sham- and doxycycline-treated animals, we evaluated the state of the BBB in both pial and parenchymal vessels by analyzing interendothelial junction proteins. The protective effect of doxycycline against junctional protein disruption was evident in some parenchymal vessels but not in pial vessels. Such differences could be associated with the lower levels of hypertrophy and MT expression in astrocytic processes as increased levels of oxidative stress compromise the integrity of the junctional complexes.48,49 In addition the lower levels of apoptosis detected in the parenchyma suggest less harmful conditions in this area. Other effects of doxycycline may also be in play. For instance, it has been shown that ischemic animals treated with doxycycline exhibited a significant reduction in the expression of the plasminogen activator uPA, and this was associated with decreased damage of the BBB.29 Likewise, in an infant rat model of pneumococcal meningitis, doxycycline significantly inhibited the production of pro-inflammatory mediators, which reduced BBB disruption and the extent of cortical brain injury.26

MMPs are linked with the disruption of the CNS barriers by their role in breaking down junctional complexes and remodeling/degrading the basal lamina associated with the CNS vasculature.20,36,50,51 During murine NCC, increased expression and activity of MMPs in astrocytes, immune cells, choroid plexus, and cerebral blood vessels is associated with the breakdown of the CNS barriers and inflammation.15 In this study, doxycycline treatment resulted in a significant reduction in the expression and activity of the MMPs studied. Doxycycline could be directly inhibiting MMPs by non-mutually exclusive mechanisms such as preventing the in vivo activation of pro-MMP zymogens by the MT1-MMP,31 blocking the active site or inducing conformational changes by binding to the Zn2+ or Ca2+ sites,52 dampening the inflammatory response associated with MMP up-regulation,53,54 or preventing MMP activation by reducing levels of plasminogen activator.29 Despite the mechanisms involved, the partial inhibition of MMPs resulted in only a marginal difference in the extent of leukocytes exiting parenchymal vessels, which correlated with a more apparent disruption of interendothelial junctions. The relative contribution of these differences observed in the parenchyma of drug-treated mice toward the better health of the animals remains uncertain.

Our results clearly show that doxycycline has a beneficial effect in murine NCC reducing both morbidity and mortality. This is the result of diminished CNS inflammation evidenced by less indication of oxidative stress, reduced MMP expression/activity in infiltrating leukocytes known to damage the extracellular matrix, and most notably a reduction in apoptosis and associated pathology. The use of doxycycline to control CNS infections promise further examination as its beneficial effects have been previously reported in humans cases of toxoplasmosis.55

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pramod K. Mishra and Sandra Ojeda for technical support.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Judy M. Teale, One UTSA Circle, San Antonio, TX 78249. E-mail: judy.teale@utsa.edu.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS 35974, AI 59703, and PO1-AI 057986.

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

Current affiliation for J.I.A.: Neuroimmunology unit, Centre de Recherche Centre Hospitalier de L’Universite de Montreal 1560 Sherbrooke E. Montreal, QC, Canada H2L 4M1.

References

- Del Brutto OH, Santibanez R, Idrovo L, Rodriguez S, Diaz-Calderon E, Navas C, Gilman RH, Cuesta F, Mosquera A, Gonzalez AE, Tsang VC, Garcia HH. Epilepsy and neurocysticercosis in Atahualpa: a door-to-door survey in rural coastal Ecuador. Epilepsia. 2005;46:583–587. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.36504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia HH, Del Brutto OH. Neurocysticercosis: updated concepts about an old disease. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:653–661. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montano SM, Villaran MV, Ylquimiche L, Figueroa JJ, Rodriguez S, Bautista CT, Gonzalez AE, Tsang VC, Gilman RH, Garcia HH. Neurocysticercosis: association between seizures, serology, and brain CT in rural Peru. Neurology. 2005;65:229–233. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000168828.83461.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AC., Jr Neurocysticercosis: updates on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:187–206. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia HH, Gonzalez AE, Evans CA, Gilman RH. Taenia solium cysticercosis. Lancet. 2003;362:547–556. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14117-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridaura C. Cysticercosis: present state of knowledge and perspectives. New York: Academic Press,; 1982:pp 107–231. [Google Scholar]

- Nash TE, Neva FA. Recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of cerebral cysticercosis. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1492–1496. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198412063112307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AC, Jr, Robinson P, Kuhn R. Taenia solium cysticercosis: host-parasite interactions and the immune response. Chem Immunol. 1997;66:209–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpio A. Neurocysticercosis: an update. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:751–762. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00454-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo BI, Llaguno P, Sandoval MA, Enciso JA, Teale JM. Analysis of immune lesions in neurocysticercosis patients: central nervous system response to helminth appears Th1-like instead of Th2. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;89:64–72. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo BI, Alvarez JI, Castano JA, Arias LF, Restrepo M, Trujillo J, Colegial CH, Teale JM. Brain granulomas in neurocysticercosis patients are associated with a Th1 and Th2 profile. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4554–4560. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4554-4560.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff RM, Kivisakk P, Kidd G. Three or more routes for leukocyte migration into the central nervous system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:569–581. doi: 10.1038/nri1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt B, Ransohoff RM. The ins and outs of T-lymphocyte trafficking to the CNS: anatomical sites and molecular mechanisms. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JI, Teale JM. Breakdown of the blood brain barrier and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier is associated with differential leukocyte migration in distinct compartments of the CNS during the course of murine NCC. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;173:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JI, Teale JM. Multiple expression of matrix metalloproteinases in murine neurocysticercosis: implications for leukocyte migration through multiple central nervous system barriers. Brain Research. 2008;1214:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AH, Edwards DR, Murphy G. Metalloproteinase inhibitors: biological actions and therapeutic opportunities. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3719–3727. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCawley LJ, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases: multifunctional contributors to tumor progression. Mol Med Today. 2000;6:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(00)01686-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. How matrix metalloproteinases regulate cell behavior. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:463–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony DC, Miller KM, Fearn S, Townsend MJ, Opdenakker G, Wells GM, Clements JM, Chandler S, Gearing AJ, Perry VH. Matrix metalloproteinase expression in an experimentally-induced DTH model of multiple sclerosis in the rat CNS. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;87:62–72. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JI, Teale JM. Evidence for differential changes of junctional complex proteins in murine neurocysticercosis dependent upon CNS vasculature. Brain Res. 2007;1169:98–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal S, Anderson P, Durbeej M, van Rooijen N, Ivars F, Opdenakker G, Sorokin LM. Dystroglycan is selectively cleaved at the parenchymal basement membrane at sites of leukocyte extravasation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1007–1019. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JI, Teale JM. Differential changes in junctional complex proteins suggest the ependymal lining as the main source of leukocyte infiltration into ventricles in murine neurocysticercosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;187:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppert D, Waubant E, Galardy R, Bunnett NW, Hauser SL. T cell gelatinases mediate basement membrane transmigration in vitro. J Immunol. 1995;154:4379–4389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg GA, Yang Y. Vasogenic edema due to tight junction disruption by matrix metalloproteinases in cerebral ischemia. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22:E4. doi: 10.3171/foc.2007.22.5.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HM, Golub LM, Cao J, Teronen O, Laitinen M, Salo T, Zucker S, Sorsa T. CMT-3, a non-antimicrobial tetracycline (TC), inhibits MT1-MMP activity: relevance to cancer. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:257–260. doi: 10.2174/0929867013373660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meli DN, Coimbra RS, Erhart DG, Loquet G, Bellac CL, Tauber MG, Neumann U, Leib SL. Doxycycline reduces mortality and injury to the brain and cochlea in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3890–3896. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01949-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong ET, Alsop D, Lee D, Tam A, Barron L, Bloom J, Gautam S, Wu JK. Cerebrospinal fluid matrix metalloproteinase-9 increases during treatment of recurrent malignant gliomas. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2008;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1743-8454-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim CW, Flynn NM, Fitzgerald FT. Penetration of oral doxycycline into the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with latent or neurosyphilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:347–348. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.2.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burggraf D, Trinkl A, Dichgans M, Hamann GF. Doxycycline inhibits MMPs via modulation of plasminogen activators in focal cerebral ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;25:506–513. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona AE, Restrepo BI, Jaramillo JM, Teale JM. Development of an animal model for neurocysticercosis: immune response in the central nervous system is characterized by a predominance of gamma delta T cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:995–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CZ, Yao JS, Huang Y, Zhai W, Liu W, Guglielmo BJ, Lin E, Yang GY, Young WL. Dose-response effect of tetracyclines on cerebral matrix metalloproteinase-9 after vascular endothelial growth factor hyperstimulation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1157–1164. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasnain SE, Begum R, Ramaiah KV, Sahdev S, Shajil EM, Taneja TK, Mohan M, Athar M, Sah NK, Krishnaveni M. Host-pathogen interactions during apoptosis. J Biosci. 2003;28:349–358. doi: 10.1007/BF02970153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo J, Aschner M, Zatta P, Vasak M. Roles of the metallothionein family of proteins in the central nervous system. Brain Res Bull. 2001;55:133–145. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese L, Kurtzhals JA, Penkowa M. Neuronal apoptosis, metallothionein expression and proinflammatory responses during cerebral malaria in mice. Exp Neurol. 2006;200:216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penkowa M. Metallothioneins are multipurpose neuroprotectants during brain pathology. Febs J. 2006;273:1857–1870. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg GA, Estrada E, Kelley RO, Kornfeld M. Bacterial collagenase disrupts extracellular matrix and opens blood-brain barrier in rat. Neurosci Lett. 1993;160:117–119. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90927-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell WC, Fingleton B, Wilson CL, Boothby M, Matrisian LM. The metalloproteinase matrilysin proteolytically generates active soluble Fas ligand and potentiates epithelial cell apoptosis. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1441–1447. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies JE, Wang L, Garcia-Oroz L, Cook LJ, Vacher C, O'Donovan DG, Rubinsztein DC. Doxycycline attenuates and delays toxicity of the oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy mutation in transgenic mice. Nat Med. 2005;11:672–677. doi: 10.1038/nm1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copin JC, Goodyear MC, Gidday JM, Shah AR, Gascon E, Dayer A, Morel DM, Gasche Y. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in apoptosis after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats and mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1597–1608. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gary DS, Mattson MP. Integrin signaling via the PI3-kinase-Akt pathway increases neuronal resistance to glutamate-induced apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1485–1496. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z, Cui J, Brown S, Fridman R, Mobashery S, Strongin AY, Lipton SA. A highly specific inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-9 rescues laminin from proteolysis and neurons from apoptosis in transient focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6401–6408. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1563-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara T, Chan PH. Reactive oxygen radicals and pathogenesis of neuronal death after cerebral ischemia. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5:597–607. doi: 10.1089/152308603770310266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YJ. The antioxidant function of metallothionein in the heart. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1999;222:263–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.1999.d01-143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaauwgeers HG, Sillevis Smitt PA, De Jong JM, Troost D. Distribution of metallothionein in the human central nervous system. Glia. 1993;8:62–70. doi: 10.1002/glia.440080108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco J, Giralt M, Penkowa M, Stalder AK, Campbell IL, Hidalgo J. Metallothioneins are upregulated in symptomatic mice with astrocyte-targeted expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Exp Neurol. 2000;163:46–54. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penkowa M, Carrasco J, Giralt M, Moos T, Hidalgo J. CNS wound healing is severely depressed in metallothionein I- and II-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2535–2545. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02535.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vela JM, Hidalgo J, Gonzalez B, Castellano B. Induction of metallothionein in astrocytes and microglia in the spinal cord from the myelin-deficient jimpy mouse. Brain Res. 1997;767:345–355. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00628-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizbai IA, Bauer H, Bresgen N, Eckl PM, Farkas A, Szatmari E, Traweger A, Wejksza K, Bauer HC. Effect of oxidative stress on the junctional proteins of cultured cerebral endothelial cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005;25:129–139. doi: 10.1007/s10571-004-1378-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzser G, Kis B, Snipes JA, Gaspar T, Sandor P, Komjati K, Szabo C, Busija DW. Contribution of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase to postischemic blood-brain barrier damage in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1318–1326. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanic AM, Madri JA. Extracellular matrix-degrading proteinases in the nervous system. Brain Pathol. 1994;4:145–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1994.tb00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong VW, Power C, Forsyth P, Edwards DR. Metalloproteinases in biology and pathology of the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:502–511. doi: 10.1038/35081571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub LM, Lee HM, Ryan ME, Giannobile WV, Payne J, Sorsa T. Tetracyclines inhibit connective tissue breakdown by multiple non-antimicrobial mechanisms. Adv Dent Res. 1998;12:12–26. doi: 10.1177/08959374980120010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DL, Desai KK, Vakili BA, Nouneh C, Lee HM, Golub LM. Clinical and biochemical results of the metalloproteinase inhibition with subantimicrobial doses of doxycycline to prevent acute coronary syndromes (MIDAS) pilot trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:733–738. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000121571.78696.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach DM, Fitridge RA, Laws PE, Millard SH, Varelias A, Cowled PA. Up-regulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 leads to degradation of type IV collagen during skeletal muscle reperfusion injury; protection by the MMP inhibitor, doxycycline. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;23:260–269. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg L, Palmertz B, Lindberg J. Doxycycline and pyrimethamine for toxoplasmic encephalitis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1993;25:157–160. doi: 10.1080/00365549309169687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.