Abstract

Although the essential role of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 in fracture healing is known, the targeted genes and molecular pathways remain unclear. Using prostaglandin E2 receptor (EP)2 and EP4 agonists, we examined the effects of EP receptor activation in compensation for the lack of COX-2 during fracture healing. In a fracture-healing model, COX-2−/− mice showed delayed initiation and impaired endochondral bone repair, accompanied by a severe angiogenesis deficiency. The EP4 agonist markedly improved the impaired healing in COX-2−/− mice, as evidenced by restoration of bony callus formation on day 14, a near complete reversal of bone formation, and an approximately 70% improvement of angiogenesis in the COX-2−/− callus. In comparison, the EP2 agonist only marginally enhanced bone formation in COX-2−/− mice. To determine the differential roles of EP2 and EP4 receptors on COX-2-mediated fracture repair, the effects of selective EP agonists on chondrogenesis were examined in E11.5 long-term limb bud micromass cultures. Only the EP4 agonist significantly increased cartilage nodule formation similar to that observed during prostaglandin E2 treatment. The prostaglandin E2/EP4 agonist also stimulated MMP-9 expression in bone marrow stromal cell cultures. The EP4 agonist further restored the reduction of MMP-9 expression in the COX-2−/− fracture callus. Taken together, our studies demonstrate that EP2 and EP4 have differential functions during endochondral bone repair. Activation of EP4, but not EP2 rescued impaired bone fracture healing in COX-2−/− mice.

Fracture healing is a complex process orchestrated by precise presentation of growth factors and cytokines that control activation, proliferation, and differentiation of the local mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells. Fracture healing begins with hematoma formation and an inflammatory response. The activated stem/progenitor cells proliferate and further differentiate into osteoblasts and chondrocytes. Endochondral bone formation takes place toward the most central avascular region of the callus. Chondrogenesis initiates directly adjacent to the surface of the cortical bone and is surrounded by less-differentiated mesenchymal progenitor cells. The subsequent expansion of the callus involves the conversion of the lingering mesenchymal progenitor cells into chondrocytes and further proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes into a calcified cartilage template that permits vascular invasion and bone formation. Areas of intramembranous bone formation flank the area of endochondral ossification, particularly along the bone surface furthest from the central fracture site where the blood supply is typically better preserved. The coordinated endochondral and intramembranous bone formation pathways eventually result in a bridging mineralized callus that re-establishes the integrity of the skeletal element.1,2,3

COX-2 is the inducible isoform of cyclooxygenase, the key rate-limiting enzyme in the prostaglandin biosynthesis pathway.4,5 Cyclooxygenase catalyzes the bis-oxygenation of arachidonic acid to form prostaglandin (PG)G2 and subsequent reduction of PGG2 to form PGH2. PGH2 is further metabolized by specific isomerases to produce various derivatives, eg, PGE2, PGD2, PGA2, thromboxanes, and prostacyclins, collectively called prostanoids. Prostanoids are labile molecules that act locally as important microenvironmental hormones mediating autocrine and/or paracrine functions. Among them, PGE2 has been shown to have both anabolic and catabolic effects on bone metabolism,6,7 acting via four distinct EP receptors (EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4) that belong to G-protein-coupled receptors.8 EP1 signaling is coupled to phospholipase C/inositol trisphosphate and leads to mobilization of intracellular calcium, whereas EP2 and EP4 receptor signaling generates increased intracellular cAMP via coupling to Gsα proteins. EP3 has generally been thought to couple to a Gi protein, leading to reduction in intracellular cAMP levels.9 EP2 and EP4 receptors are the major mediators for catabolic and anabolic effects of PGE2 in bone.10,11 Both EP2 and EP4 mediate induction of RANKL through cAMP in osteoclastogenesis.12,13 EP2 and EP4 also mediate PGE2-induced bone formation via osteoblastogenesis in animal models.11,14,15,16,17

We and others have previously shown that genetic ablation of COX-2 results in delayed and impaired fracture healing in mouse models.18,19 COX-2−/− fracture healing is characterized by marked reduction of bone formation, persistence of cartilaginous tissue, and high incidence of nonunions. Consistent with COX-2−/− phenotypes, inhibitors of COX-2 are found to delay or impair healing in animal models.19,20,21,22,23 In one such study, COX-2 inhibitor was shown to impair fracture repair when used during the early inflammatory phase of healing.25 A recent study using retrovirus overexpressing COX-2 shows that overexpression of COX-2 locally accelerates fracture healing and bone union.25 Together, these studies provide overwhelming evidence to demonstrate that COX-2 is critical for bone fracture repair.

The goal of this study was to further understand the molecular mechanisms and downstream targets of COX-2 during fracture repair. To this end, we used the COX-2−/− mouse model and selective EP agonists that have been shown to enhance bone formation in animal models.14,16,26 By performing detailed analyses using micro computed tomography (CT) and histology we show that COX-2 is induced early in the bone-healing milieu. Deficiency in COX-2 impairs initiation and completion of endochondral bone repair. Local injection of an EP2 agonist, CP-463755 marginally improved fracture healing in COX-2−/− mice whereas delivery of an EP4 agonist, CP734432, reversed the defective bone fracture healing in COX-2−/− mice. Further in vitro analyses demonstrated a differential role of EP receptor in chondrogenesis and induction of MMP-9, a matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) essential for angiogenesis during endochondral ossification. Together, the results pinpoint a key role of the COX-2/PGE2/EP4 pathway in fracture repair.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

COX-2−/− mice were originally obtained from the breeding colony maintained at the University of North Carolina. They were bred to a 129/ola genetic background and intercrossed for about 30 generations. In all experiments, wild-type littermates were used as controls for COX-2−/− mice. All animal surgery procedures were approved by the University of Rochester Institutional Committee of Animal Resources.

Experimental Materials

The nonprostanoid EP4 receptor agonist CP-73443217,27 and EP2 receptor agonist CP-463755 were obtained from Pfizer Global Research and Development (Groton, Connecticut). CP-463755 binds selectively to rat EP2 receptor with a binding IC50 of 14 nmol/L for EP2 receptor subtype and >3200 nmol/L for EP1, EP3, and EP4 receptor subtypes.27 EP1 agonist (Misoprostol) and PGE2 were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). For in vitro studies, all agonists were used at a final concentration of 10−6 M/L. Agonists for EP2 or EP4 receptor were dissolved in 5% ethanol and administered for 14 days at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day via periosteal injection at the fracture site. Drug therapy was initiated on the day of surgery and all animals were sacrificed on day 14 following fracture.

Mouse Femur Fracture Healing Model

To create a closed stabilized mid-diaphyseal femur fracture, mice received anesthesia using a mix of ketamine and xylazine. The skin and the underlying soft tissues over the left knee were incised lateral to the patellar tendon. The tendon was displaced medially, and a small hole was drilled into the distal femur using a 26-gauge needle. A stylus pin from a 25G Quincke Type spinal needle (BD Medical Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was inserted into the intramedullary canal and clipped. The wound was sutured closed. Fractures were created using a three-point bending Einhorn device as previously described.28 A Faxitron system (Faxitron X-ray, Wheeling, IL) was used to take X-ray images at the time of surgery and every week following surgery until sacrifice.

Histology and Analyses

Fractured femurs were harvested and processed for histological analyses as previously described.18 Mice were sacrificed at 3, 5, 7, 10, and 14 days after fracture. A normal mid-diaphysis femoral bone segment was used as a nonfractured, day 0 control. Femurs were disarticulated from the hip and trimmed to remove excess muscle and skin. Specimens were stored in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 2 days. The tissues were infiltrated and embedded in paraffin. Alcian blue and OrangeG staining was done as previously described.18 Histomorphometric analyses were performed using Osteometrics software to determine the area of bone, cartilage, and mesenchyme (a subtraction of total callus from bone and cartilage tissue) formation by manual tracing. Pre-existing cortical bone was excluded from the histomorphometric analysis. The total area for each sample was then used to quantify the percent areas of bone, cartilage, and mesenchyme. At least three nonconsecutive sections were used for histomorphometric analyses. The mean value represented one sample. A minimum of eight samples was included in each group. The mean of the eight samples was used in statistical analyses to determine the composition of the fracture callus. Cortical bone was excluded from the histomorphometric analysis.

Real-Time PCR Analyses

For RNA analyses, mice were placed in groups of four (n = 4) and sacrificed on days 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, and 21 following surgery. The fracture calluses were carefully dissected free of muscles and soft tissue and immediately snap frozen in a liquid nitrogen bath. Frozen tissue samples were homogenized using a liquid nitrogen-cooled mortar and pestle apparatus, and mRNA was purified via phase separation (TRIzol, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Exactly 0.5 μg of mRNA per callus was pooled and used in reverse transcription to make single-strand cDNA. Single-strand cDNA was synthesized using a commercial first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). qPCR reaction was performed using SyberGreen (ABgene, Rochester, NY) in a RotorGene real time PCR machine (Corbett Research, Carlsbad, CA). All genes were compared with a standard β-actin control. Data were assessed quantitatively using analysis of variance comparing relative levels of transcript expression as a function of time. The following primers were used for the assessment: Actin: 5′-CCCCACTGAAGCCTACAAAA-3, 5′-GGGAGGCTCCTCCATTC-3′; OC: 5′ TGCTTGTGACGAGCTATCAG-3′, 5′-GAGGACAGGGAGGATCAAGT-3′; col-2: 5′-CCACACCAAATTCCTGTTCA-3′, 5′-ACTGGTAAGTGGGGCAAGAC-3′; col-X: 5′-CTTTGTGTGCCTTTC AATCG-3′, 5′-GTGAGGTACAGCCTACCAGTTTT-3′; MMP9 - 5-TGAATCAGCTGGCTTTTGTG-3, 5-ACCTTCCAGTAGGGGCAACT-3; and COX-2: 5′-CACAGCCTACCAAAACAGCCA-3′, 5′-GCTCAGTTGAACGCCTTTTGA-3′.

MicroCT Imaging Analyses

Femurs were harvested at indicated times and scanned using a Viva microCT system (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) at a voxel size of 10.5 μm to image bone or vasculature. New bone formation and vascular volume were measured as previously described.29,30 Briefly, mice were sacrificed and given serial intracardiac injections of heparinized saline, 10% neutral buffered formalin, and a lead chromate microfil perfusion reagent (Flow Tech, Carver, MA). The whole mice were soaked in 10% neutral buffered formalin overnight at room temperature. The fractured limbs were disarticulated at the hip, and excess soft tissue was removed. Calluses were further fixed in neutral buffered formalin for 2 additional days, and decalcified in 10% EDTA for 21 days. The samples were scanned in a VivaCT Scanner (Scanco Medical AG, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) at high resolution with a 12.5-μm voxel size. An integration time of 300 ms, a current of 145 mA, and an energy setting of 55 kV were used. The threshold was chosen using two-dimensional evaluation of several slices in the transverse anatomical plane so that mineralized callus and vascular contrast reagent were identified while surrounding soft tissue was excluded. An average threshold of 250 was optimal and used uniformly for all samples. Next, each sample was contoured around the external callus and along the edge of the cortical bone. All mineralized tissues above threshold between these two boundaries were included. Thus, external soft tissues and cortical bone including the marrow cavity were excluded. Contouring of images was done every 20 axial slices proximally to distally until the callus was not visible. Histomorphometric analysis based on direct distance transform methods31,32 was subsequently performed on the three-dimensional images to quantify parameters of vascular network morphology, including vasculature volume, vessel thickness, vessel density (defined as an average number of vessels intersected by test lines passing through the three-dimensional image normalized by test line length), vessel spacing, and connectivity.29,33 We used four animals for each group. Data sets were examined using statistical assessments including analysis of variance.

In Situ Hybridization

35S-UTP-labeled sense and antisense riboprobes against murine COX-2 were synthesized from a plasmid (kindly provided by Dr. Joseph Bonventre) as previously described.34 The specific activities of the probes were determined by radioactivity. The sections were incubated in hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 0.3 M/L NaCl, 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 5 mmol/L EDTA, 10% dextran sulfate, 0.02% Ficoll, 0.02% bovine serum albumen, 0.02% polyvinyl pyrrolidone, and 0.5 mg/ml yeast RNA) containing riboprobe at 10,000 cpm/μl. Hybridization was performed at 55°C overnight. Emulsion-dipped slides were exposed for about 7 to 14 days depending on the intensity of the signals. Anti-sense probes of COX-2 and Col2a1 were further used as controls for the experiments.

Immunohistochemical Staining for Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen

Immunohistochemical staining for nuclear antigen proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) protein was performed using a staining kit purchased from Zymed (S. San Francisco, CA). The staining procedures were followed as instructed by the manufacturer. To determine the number of PCNA+ cells, three sections of each fracture samples were used to count the positive cells at the fracture junctions. The mean of the three sections represented each sample. A group of three fractured samples was included for each time point. The mean from three samples, divided by the average of the area of the periosteal callus was used in statistical analyses.

Long-Term Limb Bud Micromass Culture

Limb bud mesenchymal cells were isolated from embryos of 11.5 day time-pregnant female CD1 mice (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) as described.35 The distal 1/4 subridge (distal tips) of the limbs were pooled and digested with Dispase (1 U/ml) for 1 hour at 37°C. A total of 1 × 105 cells in 10 μl of media were placed in micromass in the center of a 24-well plate and cultured in medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 40% Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium and 60% F12. PGE2 or EP agonists (Cayman Chemical) were added every other day at a concentration of 1 μmol/L for the time indicated. No ascorbic acid or β-glycerolphosphate was added into the culture. Cartilage nodules on day 20 were stained by 0.1% Alcian blue solution at 37°C for 12 hours. Areas of cartilage were measured by tracing under the microscope using Osteometrics (OsteoMetrics, Inc., Decatur, GA). The experiments were repeated three times and representative results are presented.

Bone Marrow Stromal Cell Culture

Bone marrow cells were isolated from 2- to 3-month-old COX-2+/− mice. Femora and tibiae were removed and bone marrow cells were flushed from the marrow cavity. About 5 × 106 bone marrow cells per 10 cm2 were plated on 60-mm culture dishes cultured in α-Minimum Essential Medium containing 15% fetal bovine serum for 5 days, followed by low serum (1% fetal bovine serum) treatment for 24 hours. PGE2 or an agonist of EP1, EP2, or EP4 at 1 μmol/L was added to the culture and proteins were harvested at the indicated time points for Western blot analyses.

Mouse Sternal Chondrocyte Isolation and Culture

Three-day-old neonatal wild-type mice were sacrificed by euthanasia. The anterior rib cage and sternum were harvested, and then digested with a 3 mg/ml solution of collagenase D (Roche Applied Science, Basel, Switzerland) for 90 minutes at 37°C. The soft tissue debris was thoroughly removed. The remaining sterna and costosternal junctions were further digested in fresh collagenase D solution in Petri dishes for 5 hours. At the end of the digestion, the cells were resuspended in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum. PGE2 (Cayman Chemicals) or EP agonists were added at a concentration of 1 μmol/L for the indicated times following serum starvation of the culture for 24 hours.

Gelatin Zymography

Fracture calluses derived from wild-type mice were harvested and cultured in serum-free medium overnight. Supernatant was collected and loaded into zymogram gel containing 1 mg/ml gelatin. After electrophoresis, the gel was soaked in 0.25% Triton X-100 for 1 hour and washed in collagenase buffer for 18 hours followed by Coomassie blue staining and de-staining. Culture media bone marrow stromal cells were also collected and used for zymography to determine MMP-9 activity as described.36

Western Blot Analyses

Cells were lysed in Golden lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science). The protein extracts (10 μg) were separated using NuPAGE BisTris gels (Invitrogen). Gels were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (PerkinElmer Life Sciences Waltham, MA) and probed with anti–phospho-extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK)1/2, anti-ERK1/2, anti-phospho-AKT, anti-AKT (Cell Signaling Technology Inc. Danvers, MA) and anti–β-actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance between experimental groups was determined using one-way analysis of variance and a Tukey’s posthoc test (GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For all nonquantitative data, we have repeated at least once and the representative results were presented.

Results

Delayed Initiation and Progression of Periosteal Endochondral Bone Formation in COX-2−/− Mice

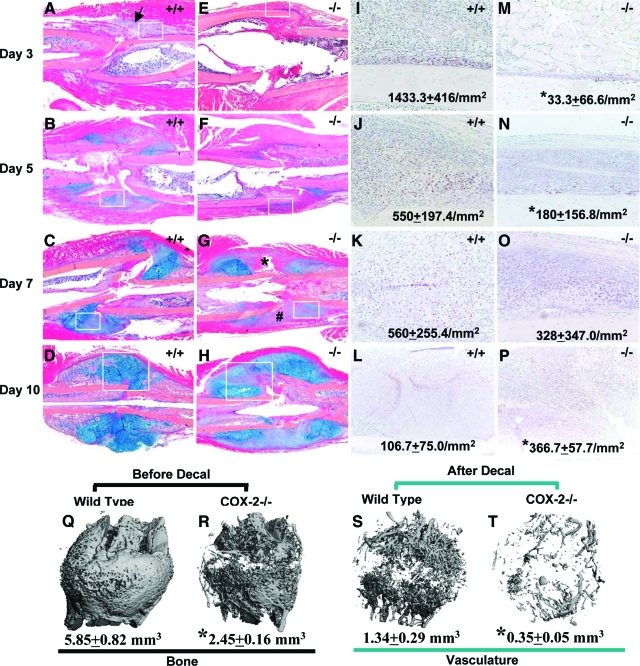

Fracture callus from both wild-type and COX-2−/− mice was examined histologically at post-fracture days 3, 5, 7, and 10 (Figure 1, A–P). At day 3, wild-type samples showed rapid induction of cellular infiltration in the surrounding periosteal envelope (Figure 1A, arrow). The periosteum adjacent to the fracture site became thickened, with the majority of cells staining positive for PCNA (Figure 1I). In contrast, COX-2−/− mice demonstrated a near absence of cellular filtration and a 90% to 100% reduction of PCNA+ periosteal progenitor cells (Figure 1, E and M). At day 5, chondrogenesis in COX-2−/− mice was markedly reduced compared with wild-type as indicated by Alcian Blue staining (Figure 1, B versus F). PCNA+ progenitors were significantly reduced along periosteum in COX-2−/− mice (Figure 1, J versus N). At day 7, the cartilage in wild-type mice was further expanded (Figure 1C). In contrast, cartilage expansion was reduced in COX-2−/− mice, with remnants of unresolved hematoma (Figure 1G, indicated by *) and large amount of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells at cortical junctions (Figure 1G, indicated by #). By day 10, most chondrocytes in wild-type mice ceased to proliferate and undergo terminal hypertrophy, as indicated by PCNA staining (Figure 1L). On the contrary, in COX-2−/− mice, we found poorly differentiated cartilaginous callus with a large amount of mesenchymal cells present at the fracture junction (Figure 1H, boxed). Although hypertrophic chondrocytes were observed, PCNA staining indicated that the majority of cells within periosteal callus remained in a proliferative stage (Figure 1P), suggesting markedly delayed hypertrophy in the COX-2−/− callus.

Figure 1.

Delayed initiation and progression of periosteal endochondral bone formation in femur fractures of COX-2−/− mice. Representative H&E/Alcian blue stained sections of wild-type (A–D) and COX-2−/− (E–H) fracture callus on post-fracture days 3, 5, 7, and 10 are shown at ×4 magnification. Of note is the absence of cellular infiltration in COX-2−/− mice (E), which is clearly evident in wild-type mice on day 3 post-fracture (arrow in A). Persistent residual hematoma (asterisk) and undifferentiated mesenchymal cells at cortical junctions (#) were observed in COX-2−/− mice on day 7 (G). Parallel sections were stained for PCNA, and the tissue corresponding to the boxed region in A–H were photographed at ×20 magnification (I–P). The numbers represent the mean of PCNA+ cells/mm2 ± SEM in each group (n = 3). *P < 0.05. Representative microCT images of wild-type and COX-2−/− femurs at post-fracture day 14 are shown before (Q, R) and after decalcification (S,T) with total bone volume and vascular volume indicated below. Of note is the marked reduction of neovascularization in COX-2−/− callus.

Marked Reduction of Osteogenesis and Angiogenesis in COX-2−/− Fracture Callus

Quantitative microCT analyses were used to evaluate bone formation and neovascularization at day 14 post-fracture in wild-type and COX-2−/− mice. Representative microCT images demonstrated a marked reduction of mineralized tissue formation and a severe lack of functional vascular networks in COX-2−/− mice (Figure 1, Q–T). Quantitative morphometric analyses of microCT images demonstrated a 2.5-fold reduction of new bone and 3.75-fold reduction of total vessel volume in the COX-2−/− mice compared with wild-type controls. Accordingly, vessel separation was increased by 1.5-fold, the average vessel thickness was decreased by 25% and the vessel connectivity was reduced to 10% of the wild-type control.

Early Induction of COX-2 Is Required for Initiation and Completion of Endochondral Bone Repair

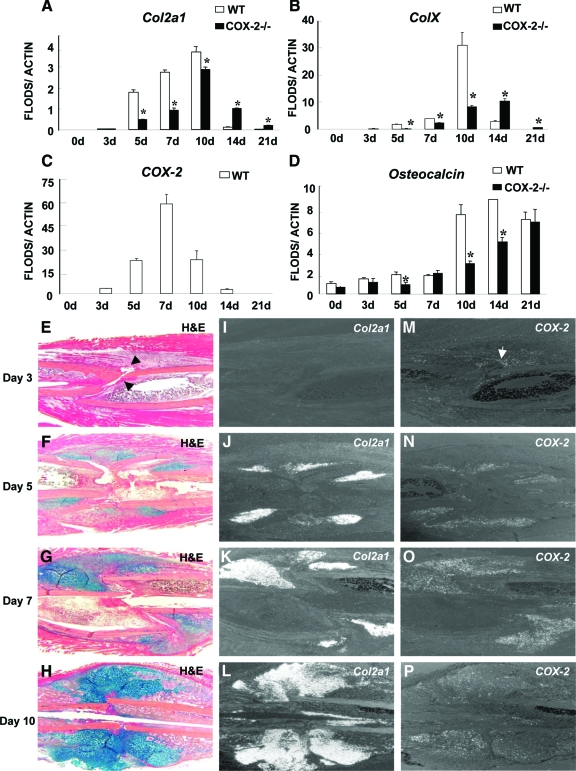

Real-time PCR analyses were performed to determine the expression of genes associated with endochondral bone repair (Figure 2, A–D). In wild-type mice, chondrocyte markers Col2a1 and ColX appeared on day 5 and peaked on day 10. By day 14, expressions of both genes were markedly reduced, indicating completion of endochondral bone formation. In COX-2−/− mice, expressions of Col2a1 and ColX were delayed and diminished on days 5 and 7. The ColX and Col2a1 ratio was reduced on day 10, indicating delayed chondrocyte differentiation. At day 14, Col2a1 and ColX expression persisted in COX-2−/− mice accompanied by a decreased level of osteocalcin expression.

Figure 2.

Up-regulation of COX-2 expression correlated with impaired initiation and completion of endochondral bone repair in COX-2−/− mice. Real-time PCR analyses were performed using RNA collected from wild-type or COX-2−/− callus on days 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, and 21 post-fracture. Col2a1, ColX, COX-2, and osteocalcin gene expression is shown (A–D). Each time point included at least eight fractured samples. *P < 0.05 (n = 8). Representative H&E/Alcian blue sections of wild-type (WT) fracture callus illustrate the progression of early endochondral bone healing (E–H). Arrows in E indicate Hematoma formed at the cortical junction. In situ hybridizations demonstrate the expression of Col2a1 (I–L) and COX-2 (M–P) on post-fracture days 3, 5, 7, and 10 in adjacent tissue sections. Of note is that the induction of COX-2 mRNA is observed before chondrogenesis in cellular infiltration as early as day 3 (arrow in M). The expression peaked at day 7 in chondroprogenitors, chondrocytes in the fracture callus.

The temporal expression of COX-2 mRNA during fracture healing was also examined. COX-2 was increased as early as day 3, peaked at day 7, and reduced to basal level by day 21 (Figure 2, C, M–P). In situ hybridization confirmed that initial COX-2 expression was largely localized within the early cellular milieu with more intense staining around hematoma at the cortical bone junctions before chondrogenesis (Figure 2, E, I, and M, arrows). By day 5, COX-2 was found in almost all Col2a1 expressing chondroprogenitors and in the early cellular infiltration in bone marrow and mesenchymal cells along the periosteal surface (Figure 2, F, J, N). A similar pattern of expression was found at day 7 in chondroprogenitors and proliferating chondrocytes, significantly overlapping with Col2a1 expression (Figure 2, G, K, and O). The COX-2 expression correlated with early induction of chondrogenesis and early expansion of cartilaginous callus such that by day 10, COX-2 expression was markedly reduced in hypertrophic chondrocyte (Figure 2, H, L, and P).

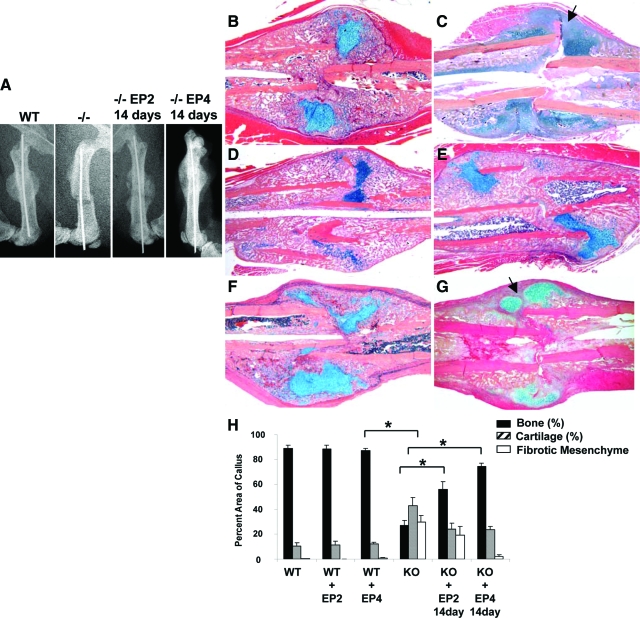

Periosteal Injection of EP4 Agonists Markedly Improved the Impaired Periosteal Endochondral Bone Repair in COX-2−/− Mice

Both EP2 and EP4 agonists were shown to enhance bone formation and bone repair in animal models. To determine whether EP agonists can compensate for the lack of COX-2 during fracture healing, EP2 or EP4 agonist was injected to the fracture site of wild-type and COX-2−/− mice at a dose of 20 mg/day/kg for 14 days (Figure 3b–g). Remarkably, we found that EP4 agonist CP-734432 nearly reversed the impaired fracture healing phenotype in COX-2−/− mice (Figure 3, B–E). X-ray showed apparent hard callus formation on day 14 in COX-2−/− mice, which was completely absent in COX-2−/− controls (Figure 3A). Histology further showed that EP4 agonist-treated callus had marked induction of periosteal bone formation, improved vascular invasion, and complete elimination of undifferentiated mesenchymal tissue in COX-2−/− mice (Figure 3, C versus E). This remarkable improvement was observed not only at the outer periosteal surface but also in the intramedullary area that displayed diminished bone formation in untreated COX-2−/− mice. Histomorphometry by measuring the percent area of bone, cartilage, and mesenchyme in wild-type and COX-2−/− callus showed that EP4 agonist eliminated the undifferentiated mesenchyme at the fracture site and further led to the restoration of 91% bone formation in EP4 treated COX-2−/− mice (n = 8, P < 0.05). When compared with wild-types, we found that the average percentage area of cartilage in COX-2−/− mice treated with EP4 agonists was still higher (P < 0.05), indicating the presence of some remaining residual-cartilage presence in COX-2−/− mice (Figure 3H).

Figure 3.

Rescue of impaired fracture healing in COX-2−/− mice by EP agonists. Representative X-rays (A) and H&E/Alcian blue sections (B–G) of wild-type (WT) and COX-2−/− fracture callus on post-fracture day 14 are shown. Compared with WT littermates (B), COX-2−/− mice demonstrated reduced endochondral bone formation and persistent undifferentiated mesenchyme at the fracture site (C). Arrow in C indicates undifferentiated mesenchymal cells. Treatment with EP4 agonist in wild-type increased the size of the callus as well as bone density in fracture callus (D). Treatment with EP4 agonist in COX-2−/− mice restored endochondral bone formation in fracture callus (E). Treatment of EP2 agonist showed limited effects in WT mice (F) but resulted in a modest increase in bone formation in COX-2−/− mice (G). Fibrotic tissue remained in EP2 treated group (arrow in G). Quantitative histomorphometric analyses for the percent area of bone, cartilage, and mesenchyme in WT and COX-2−/− fracture callus on day 14 are presented as mean ± SEM (H). *P < 0.05, n = 8.

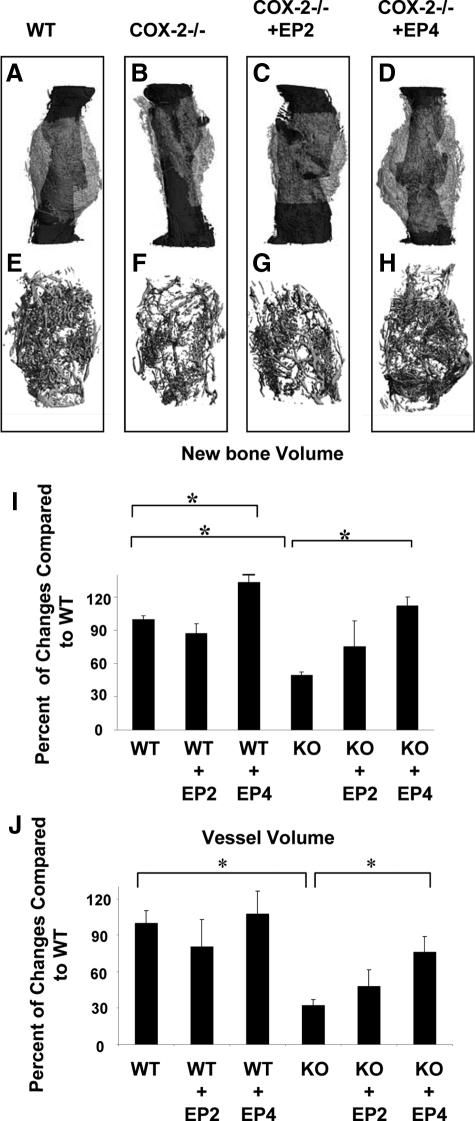

Consistent with histological findings, microCT three-dimensional volumetric quantification for bone formation showed that EP4 agonist reversed the impaired bone formation in COX-2−/− mice at day 14 post-fracture (Figure 4, A–H). Consistently, microCT analysis demonstrated a 2.4-fold increase of bone volume in COX-2−/− mice treated with EP4 agonist. Along with increased bone formation, vascularity of the fracture callus was markedly improved in the COX-2−/− mice treated with EP4 agonist. Quantitative measurements demonstrated about a 2.3-fold increase in total vessel volume in the knockout fracture callus following EP4 agonist treatment (Figure 4J, P < 0.05, n = 4), achieving 70% of the total vessel volume of the wild-type mice. The incomplete rescue of vascularity in COX-2−/− mice by EP4 agonist could be related to the residual cartilage presence in the knockout mice as evidenced by histological analyses (Figure 3H, P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Rescue of impaired fracture healing in COX-2−/− mice by EP agonists. Representative microCT image of periosteal new bone formation (A–D) and neovascularization (E–H) in wild-type (WT), COX-2−/−, and COX-2−/− treated with EP2 or EP4 agonist are shown. Quantitative analyses for new bone volume (I) and total vessel volume (J) are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, n = 4.

EP4 agonist CP-734432 also exhibited a positive effect on the wild-type mice as determined by microCT analyses. Histologically, EP4 agonist did not accelerate the fracture repair as evidenced by normal percent ratio of bone and cartilage in EP4-treated or nontreated samples (Figure 3H). However, we found that EP4 treated samples had more trabecular bone and a larger callus. MicroCT analyses demonstrated a 23% increase in bone formation in wild-type samples treated with EP4 agonist (Figure 4I, n = 4, PP < 0.05).

Compared with EP4 agonist, the EP2 agonist CP- 463755 demonstrated a modest improvement in bone formation in the knockout mice. However, histologically, this treatment group exhibited variable amounts of poorly differentiated cartilage and fibrotic tissues at the cortical junctions (Figure 3, F,G, arrow). Quantification by histomorphometry and microCT demonstrated an average of 50% improvement in bone formation following treatment with EP2 agonist (Figure 4, C,G, P < 0.05, n = 4).

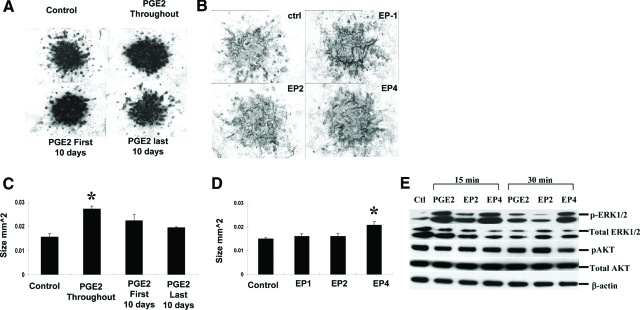

PGE2 and EP4 Agonist Increased Cartilage Volume in Long-Term Limb Bud Micromass Culture

The marked differences in response to EP2 or EP4 agonist during COX-2−/− fracture healing suggest a differential role of EP receptor in mediating COX-2 dependent endochondral repair. Since EP4 agonist was able to eliminate the undifferentiated mesenchyme in COX-2−/− mice, whereas EP2 agonist could not, we test the ability of EP agonists in stimulating cartilage nodule formation in E11.5 mouse limb bud micromass cultures. The addition of PGE2 every other day for 16 to 20 days in this culture resulted in a modest but significant increase in size of the Alcian blue-positive cartilage nodules (Figure 5, A and C). Interestingly, data show that the early treatment was critical for the anabolic effects of PGE2. The treatment during first 10 days of culture enhanced cartilage nodule formation on day 20 whereas the treatment after day 10 resulted in minimal increase in size of the nodules. Among all of the selective agonists, we found that only the EP4-specific agonist CP734432 had a significant positive effect on the volume of cartilage nodule formation (Figure 5, B and D).

Figure 5.

PGE2 and EP4 agonists enhanced cartilage nodule formation in long-term limb bud micromass culture. Representative Alcian blue staining of 20-day micromass cultures treated with PGE2 (A) or selective EP agonists (B). The size of Alcian blue-positive nodules was measured by manual tracing under microscopy using Osteometrics (C, D), *P < 0.05, n = 4. The experiments were repeated three times and the representative results are shown. Primary chondrocytes were isolated from neonatal mouse rib cage and treated with PGE2 and selective EP agonists as described in the Materials and Methods. Western blot analyses demonstrate marked induction of phosphorylation of ERK1/2 by PGE2 and EP4 agonist (E).

Since COX-2 was found highly expressed in chondrocytes in early fracture callus, we examined the effects of PGE2 and EP agonist in primary chondrocyte cultures. Western blot analyses were performed in primary chondrocytes isolated from the rib cage of neonatal wild-type mice. Treatment of PGE2 and EP4 agonist markedly enhanced phosphorylation of ERK1/2, strongly indicating that PGE2 and EP4 activation is mitogenic in the primary chondrocyte culture. Compared with EP4 agonist, EP2 activation elicited a smaller effect on ERK1/2 activation (Figure 5E). In contrast to ERK phosphorylation, AKT phosphorylation, which is known to activate apoptotic pathway, remained unaffected by PGE2 or EP agonists.

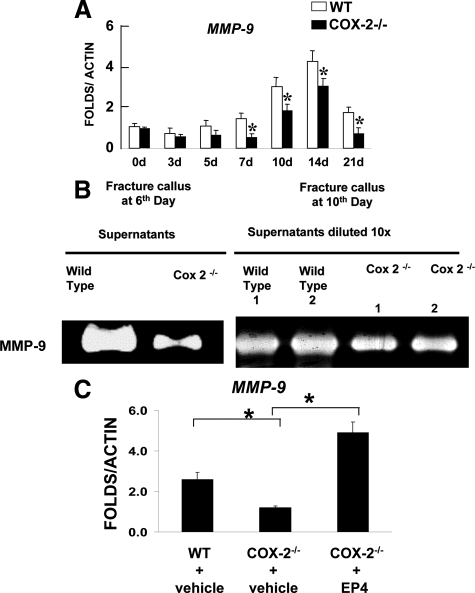

PGE2 and EP4 Agonist Stimulated MMP-9 Expression, Compensating the Persistent Reduction of MMP-9 in COX-2−/− Fracture Callus

The marked reduction of angiogenesis suggests a potential involvement of COX2 in modulating angiogenesis during fracture healing. To determine the potential downstream target genes that implicate the COX-2 pathway in repair, we performed real time reverse transcription-PCR analyses to examine the expression of a panel of angiogenic genes that are essential for endochondral bone formation in wild-type and COX-2−/− callus. To our surprise, we found normal expression of both vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and HIF1α in COX-2−/− fracture callus. Instead, we identified a persistent reduction of matrix metalloproteinase MMP-9 mRNA levels in COX-2−/− callus (Figure 6A). The reduced MMP-9 expression in COX-2−/− was further confirmed by gelatin zymography using supernatant collected from the overnight culture of the wild-type and COX-2−/− fracture callus. COX-2−/− callus exhibited marked reduction of MMP-9 activity at post-fracture day 6 and day 10 (Figure 6B). To determine whether EP4 agonist treatment can compensate for the reduced level of MMP-9 in COX-2−/− fracture callus, expression of MMP-9 was examined in EP4 agonist-treated fracture callus at day 10 post-fracture. Remarkably, we found that while MMP-9 expression is reduced in COX-2−/− fracture callus, EP4 agonist stimulated a fourfold increase in expression of MMP-9 in COX-2−/− fracture callus (Figure 6C, n = 4, P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Reduction of MMP-9 in COX-2−/− fracture callus and compensation by EP4 agonist. Real-time PCR analyses were performed using RNA collected from wild-type or COX-2−/− callus on days 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, and 21 post-fracture. MMP-9 expression was markedly reduced in COX-2−/− fracture callus throughout the repair process (A). *P < 0.05, n = 8. Gelatin zymography demonstrated reduced MMP-9 activity in COX-2−/− fracture callus at days 6 and 10 (B). Total RNA was harvested from the fracture callus treated with or without EP4 agonist on day 10. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR shows that treatment of EP4 agonist restores the expression of MMP9 in day 10-fracture callus of COX-2−/− mice (C). n = 4, *P < 0.05.

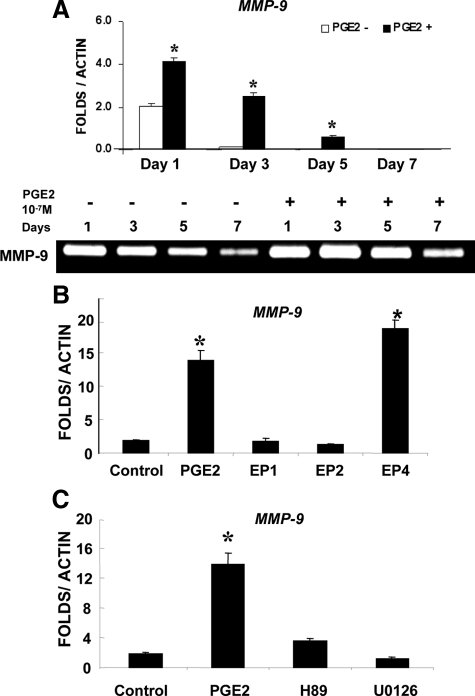

To determine the potential regulatory mechanisms of MMP-9 expression by PGE2, we examined MMP-9 expression in bone marrow stromal cell cultures following treatment of PGE2 and EP agonists. Real time reverse transcription-PCR analysis showed about two-fold induction of MMP-9 on day 1 following PGE2 treatment. The induction peaked at day 3 and diminished by day 7. Consistent with mRNA expression, gelatin zymography showed a similar time course of accumulation of MMP-9 following the treatment of PGE2 (Figure 7A). Selective EP receptor agonists were used to determine which subtype of EP receptors mediates the induction of MMP-9 by PGE2. Among the three agonists used, only EP4 agonist showed robust induction of MMP-9 (Figure 7B). The induction was efficiently blocked by both PKA inhibitor HA89 and ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 (Figure 7C), indicating the involvement of PKA and ERK1/2 downstream of EP4 receptor signaling.

Figure 7.

Activation of EP4 receptor-induced MMP-9 expression in bone marrow stromal cell culture. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR analyses shows that MMP-9 expression is markedly induced by PGE2 in bone marrow stromal cell cultures. Consistently, gelatin zymography shows MMP-9 activity is persistently higher in samples treated with PGE2 (A). PGE2 and selective EP agonists were used to treat bone marrow stromal cells. Only PGE2 and EP4 agonist demonstrate markedly induction of MMP-9 expression (B). The induction is blocked by PKA inhibitor H89 and an ERK1/2 kinase inhibitor U0126 (C). *P < 0.05.

Discussion

The essential role of COX-2 in skeletal repair has been well established given the overwhelming genetic evidence.18,19 Yet, the mechanism and the signaling pathways downstream of COX-2 remain unclear. Using a COX-2−/− mouse model, in this study we demonstrate that deletion of COX-2 affects multiple cellular events that are essential for efficient bone fracture healing. Deletion of COX-2 impaired early cellular recruitment and periosteal progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation. Deletion of COX-2 markedly impaired chondrogenesis, osteogenesis, and angiogenesis. The phenotypes of COX-2−/− callus were consistent with transient induction of COX-2 in injury milieu and in progenitor cells of chondrocytes, demonstrating that COX-2 is indispensable for a cascade of events that lead to efficient endochondral ossification during the healing process. The shift of COX-2 expression during fracture repair from infiltrating cells to chondroprogenitors and proliferating chondrocytes further suggests that the mechanism of action of COX-2 in the fracture repair is highly complicated and involves temporal and spatial coordination of inflammatory cells as well as progenitors.

Both EP2 and EP4 receptor were found to be expressed in periosteum, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes.11,17,37 Using selective agonists of PGE2 receptors, we further demonstrate that EP4 signaling plays a key role in COX-2 mediated repair. Delivery of EP4 agonist reversed the impaired fracture healing in COX-2−/− mice, as evidenced by elimination of undifferentiated mesenchyme cells and marked improvement of osteogenesis and angiogenesis. Immunohistochemistry and real time PCR analyses further confirmed the expression of EP4 receptor in fracture callus (see supplemental Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Although EP2 agonist demonstrated positive effects on fracture healing in COX-2−/− mice, the efficacy of EP2 receptor agonist in COX-2−/− mice is weak in restoring bone formation, eliminating fibrotic tissue, and improving neovascularization. An EP2 agonist has been shown to enhance fracture healing in rats and dogs.14,15 The reduced potency of the compound in COX-2−/− mice may be associated with a species difference in EP2 and EP4 receptors. However, based on our in vitro study, EP2 agonist had no discernible effects on chondrogenesis and MMP-9 induction, suggesting that the two receptors play differential roles during repair.

Among metabolites of COX-2, PGE2 has been shown to have a strong anabolic effect on bone formation in animal models and in humans.38,39,40,41 There are also reports that show PGE2 exerts differential effects on chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation.42,43,44,45 Using a long-term mouse limb bud mesenchymal stem cell culture, which recapitulates chondrogenesis, chondrocyte differentiation, and mineralization,35 we previously showed that the prolonged treatment of PGE2 in this culture led to a modest but significant induction of total cartilage formation.35 In our current study, we found that the treatment of PGE2 demonstrated a stage-dependent effect on differentiation such that the increased cartilage nodule formation was only observed when PGE2 was added at the early stage of mesenchymal differentiation. PGE2 added after 10 days exhibited no effects on cartilage formation. This finding is consistent with the transient expression of COX-2 during repair, underscoring highly coordinated effects of COX-2 during the repair process.

Although both EP2 and EP4 receptors mediate induction of cAMP via activation of Gsα, the amino acid identity between the two receptors is merely 31%. EP4 receptor has the longest intracellular C terminus and a relatively long intracellular third loop. EP4 can be internalized following binding to PGE2, whereas EP2 cannot be internalized.46,47 It is also reported that EP4-selective action may be related to the fact that EP4, but not EP2 couples to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in addition to activation of adenylate cyclase.48,49 In our current study, we found that in primary chondrocyte cultures PGE2/EP4 agonist markedly enhanced phosphorylation of ERK1/2, suggesting a strong mitogenic effect of PGE2/EP4 pathway on chondrocytes. These data are consistent with the in vivo data that demonstrated the reduced number of PCNA+ cells during initiation of the repair in COX-2−/− mice and marked recovery of endochondral bone repair in COX-2−/− mice following EP4 agonist treatment. To further determine the potential involvement of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathway in PGE2 induced chondrocyte proliferation, we examined AKT phosphorylation in primary chondrocytes; our data showed no apparent effects of PGE2/EP agonists on AKT phosphorylation in these cells.

The involvement of COX-2 in angiogenesis has been demonstrated during tumor formation.50,51 COX-2 has been shown to be involved in endothelial proliferation, migration, and sprouting.52,53,54,55 Recent data suggest that COX-2 also regulates molecules implicated in endothelial trafficking with pericytes, an interaction crucial to vessel stability.56,57 PGE2 enhances the expression of endothelial genes such as VEGF and CXCR4, stimulating endothelial cell migration and survival.58 Using quantitative microCT analyses, we observed a marked reduction of angiogenesis in COX-2−/− fracture callus. However, we found that the expression of a number of angiogenic factors, including VEGFs and HIF1α are normal in early COX-2−/− callus. Instead, we found that COX-2−/− mice have persistent reduction of MMP-9 expression throughout the fracture repair process.

MMP-9 has been linked with angiogenesis during endochondral ossification.59,60 MMP-9 deficient mice demonstrate delayed endochondral ossification coupled with deficient angiogenesis, a phenotype that can be rescued by bone marrow transplantation and VEGF reconstitution. Using in situ hybridization, MMP9 is primarily localized in chondroclasts at the invasion front within cartilaginous tissue (see supplemental Figure S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), strongly suggesting that MMP-9 plays a critical role in vascular invasion coupled endochondral bone formation. MMP-9−/− mice exhibit deficient fracture healing and impaired angiogenesis.61 Local injection of active VEGF can reverse the delayed fracture healing in MMP-9−/− mice, indicating a critical role of MMP-9 in controlling the release of active angiogenic factors such as VEGFs from cartilage matrix. In addition to angiogenesis, MMP-9 has been shown to modulate inflammation and early cellular recruitment during wound healing.62,63,64 A role of MMP-9 in scar tissue formation has also been recognized recently.65,66 Although we cannot detect MMP-9 expression at day 3 by in situ hybridization, we found abundant MMP-9 activity (as examined by zymography) in the fracture callus at day 6. Furthermore, MMP-9 activity was significantly reduced at day 6 in COX-2−/− mice, indicating that COX-2-dependent MMP-9 could be involved in modulating early cellular recruitment, migration, and angiogenesis. Using bone marrow stromal cell culture, we found that PGE2 markedly enhanced MMP-9 expression. The induction of MMP-9 by PGE2 was selectively mediated through EP4 receptor signaling, since only EP4 agonist was capable of stimulating MMP-9 induction in bone marrow stromal cell culture. Furthermore, the inhibition of PKA signaling and ERK1/2 phosphorylation completely blocked MMP-9 induction by PGE2, indicating the involvement of PKA/ERK1/2 pathway. The differential function of EP2 and EP4 in regulating chondrogenesis and MMP-9 expression may partly explain the difference of EP2 and EP4 agonist in their efficacy in restoring defective healing in COX-2−/− mice.

Despite the marked improvement of EP4 receptor agonist on COX-2−/− fracture repair, we found that EP4 agonist-treated fracture callus had a higher percentage of residual cartilage in COX-2−/− callus. The presence of residual cartilage could be due to the stimulation of chondrogenesis by EP4 agonist, which was supported by a significant increase in the overall size of the callus in the EP4-treated group (P <0.05). It could also be due to the limited penetration of EP4 agonist into the dense cartilage tissue, resulting in an incomplete rescue of chondrocyte differentiation, remodeling, and vascular invasion. In addition, involvement of COX-2 metabolites other than PGE2 could also be the cause of the delayed healing. Further investigation is warranted.

In summary, using a COX-2-deficient mouse model, we demonstrate that deficiency of COX-2 affects a cascade of events leading to the completion of endochondral bone healing. EP4 receptor signaling plays an important role downstream of COX-2 in fracture repair. Agonist of EP4 receptor induced MMP-9 expression and further exerted a positive effect on chondrogenesis. Local administration of EP4 agonist to the fractured site reversed the impaired fracture healing in COX-2−/− mice. Collectively, our study suggests that EP4 could be an effective target for improved angiogenesis and endochondral bone repair.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mei Li (Pfizer Inc, Gordon, CT) and Amish Naik for helpful discussion during the preparation of the manuscript. We also thank Krista Canary, Lisa Flick, and Laura Yanoso, for their assistance with histology and microCT analyses, and Kimberly Napoli for her assistance in editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Xinping Zhang, The Center for Musculoskeletal Research, University of Rochester Medical Center, 601 Elmwood Avenue, Rochester, NY 14642. E-mail: Xinping_Zhang@URMC.rochester.edu.

Supported by grants from the Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation and the NIH (AR051469, AR46545, P50AR054041).

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Einhorn T. The cell and molecular biology of fracture healing. Clin Orthop. 1998;355S:S7–S21. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199810001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einhorn TA. The science of fracture healing. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:S4–S6. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200511101-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstenfeld LC, Cullinane DM, Barnes GL, Graves DT, Einhorn TA. Fracture healing as a post-natal developmental process: molecular, spatial, and temporal aspects of its regulation. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:873–884. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschman HR. Prostaglandin synthase 2. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1996;1229:125–140. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(95)00194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WL, DeWitt DL, Garavito RM. Cyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Ann Rev Biochem. 2000;69:145–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raisz LG, Pilbeam CC, Fall PM. Prostaglandins: mechanisms of action and regulation of production in bone. Osteoporos Int. 1993;3 Suppl 1:136–140. doi: 10.1007/BF01621888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi H, Pilbeam CC, Harrison JR, Raisz LG. The role of prostaglandins in the regulation of bone metabolism. Clin Orthop. 1995;96:36–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S. Prostaglandin E receptors. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11613–11617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breyer RM, Bagdassarian CK, Myers SA, Breyer MD. Prostanoid receptors: subtypes and signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:661–690. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzawa T, Miyaura C, Inada M, Maruyama T, Sugimoto Y, Ushikubi F, Ichikawa A, Narumiya S, Suda T. The role of prostaglandin E receptor subtypes (EP1. EP2, EP3, and EP4) in bone resorption: an analysis using specific agonists for the respective EPs. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1554–1559. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.4.7405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreb M, Grosskopf A, Shir N. The anabolic effect of PGE2 in rat bone marrow cultures is mediated via the EP4 receptor subtype. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:E376–E383. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.2.E376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Okada Y, Pilbeam CC, Lorenzo JA, Kennedy CR, Breyer RM, Raisz LG. Knockout of the murine prostaglandin EP2 receptor impairs osteoclastogenesis in vitro. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2054–2061. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.6.7518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K, Kaneko H, Choudhary S, Pilbeam CC, Lorenzo JA, Akatsu T, Kugai N, Raisz LG. Biphasic effect of prostaglandin E2 on osteoclast formation in spleen cell cultures: role of the EP2 receptor. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:23–29. doi: 10.1080/14041040510033842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Ke HZ, Qi H, Healy DR, Li Y, Crawford DT, Paralkar VM, Owen TA, Cameron KO, Lefker BA, Brown TA, Thompson DD. A novel, non-prostanoid EP2 receptor-selective prostaglandin E2 agonist stimulates local bone formation and enhances fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:2033–2042. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.11.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paralkar VM, Borovecki F, Ke HZ, Cameron KO, Lefker B, Grasser WA, Owen TA, Li M, DaSilva-Jardine P, Zhou M, Dunn RL, Dumont F, Korsmeyer R, Krasney P, Brown TA, Plowchalk D, Vukicevic S, Thompson DD. An EP2 receptor-selective prostaglandin E2 agonist induces bone healing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6736–6740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1037343100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke HZ, Crawford DT, Qi H, Simmons HA, Owen TA, Paralkar VM, Li M, Lu B, Grasser WA, Cameron KO, Lefker BA, DaSilva-Jardine P, Scott DO, Zhang Q, Tian XY, Jee WS, Brown TA, Thompson DD. A nonprostanoid EP4 receptor selective prostaglandin E2 agonist restores bone mass and strength in aged, ovariectomized rats. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:565–575. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.051110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Oida H, Kobayashi T, Maruyama T, Tanaka M, Katayama T, Yamaguchi K, Segi E, Tsuboyama T, Matsushita M, Ito K, Ito Y, Sugimoto Y, Ushikubi F, Ohuchida S, Kondo K, Nakamura T, Narumiya S. Stimulation of bone formation and prevention of bone loss by prostaglandin E EP4 receptor activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4580–4585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062053399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Schwarz EM, Young DA, Puzas JE, Rosier RN, O'Keefe RJ. Cyclooxygenase-2 regulates mesenchymal cell differentiation into the osteoblast lineage and is critically involved in bone repair. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1405–1415. doi: 10.1172/JCI15681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon AM, Manigrasso MB, O'Connor JP. Cyclo-oxygenase 2 function is essential for bone fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:963–976. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.6.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S, Ma T, Trindade M, Ikenoue T, Matsuura I, Wong N, Fox N, Genovese M, Regula D, Smith RL. COX-2 selective NSAID decreases bone ingrowth in vivo. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:1164–1169. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon LS, Lanza FL, Lipsky PE, Hubbard RC, Talwalker S, Schwartz BD, Isakson PC, Geis GS. Preliminary study of the safety and efficacy of SC-58635, a novel cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor: efficacy and safety in two placebo-controlled trials in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, and studies of gastrointestinal and platelet effects. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1591–1602. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199809)41:9<1591::AID-ART9>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon AM, Sabatino CT, O'Connor JP. Effects of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors on fracture healing. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 2001;26:205. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstenfeld LC, Thiede M, Seibert K, Mielke C, Phippard D, Svagr B, Cullinane D, Einhorn TA. Differential inhibition of fracture healing by non-selective and cyclooxygenase-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:670–675. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon AM, O'Connor JP. Dose and time-dependent effects of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition on fracture-healing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:500–511. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundle CH, Strong DD, Chen ST, Linkhart TA, Sheng MH, Wergedal JE, Lau KH, Baylink DJ. Retroviral-based gene therapy with cyclooxygenase-2 promotes the union of bony callus tissues and accelerates fracture healing in the rat. J Gene Med. 2008;10:229–241. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre JI, Leal ME, Rivera MF, Vanegas SM, Jorgensen M, Wronski TJ. Effects of basic fibroblast growth factor and a prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype 4 agonist on osteoblastogenesis and adipogenesis in aged ovariectomized rats. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:877–888. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Healy DR, Li Y, Cameron K, Ke HZ, Lefker BA, Rosati RL, Thompson DD. CP-463,755. A non-prostanoid EP2 receptor agonist stimulates fracture healing in a rat femoral fracture model. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:S343. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.11.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnarens F, Einhorn TA. Production of a standard closed fracture in laboratory animal bone. J Orthop Res. 1984;2:97–101. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100020115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvall CL, Robert Taylor W, Weiss D, Guldberg RE. Quantitative microcomputed tomography analysis of collateral vessel development after ischemic injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H302–H310. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00928.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvall CL, Taylor WR, Weiss D, Wojtowicz AM, Guldberg RE. Impaired angiogenesis, early callus formation, and late stage remodeling in fracture healing of osteopontin-deficient mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:286–297. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand T, Laib A, Muller R, Dequeker J, Ruegsegger P. Direct three-dimensional morphometric analysis of human cancellous bone: microstructural data from spine, femur, iliac crest, and calcaneus. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1167–1174. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.7.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand T, Ruegsegger P. Quantification of Bone Microarchitecture with the Structure Model Index. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 1997;1:15–23. doi: 10.1080/01495739708936692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guldberg RE, Ballock RT, Boyan BD, Duvall CL, Lin AS, Nagaraja S, Oest M, Phillips J, Porter BD, Robertson G, Taylor WR. Analyzing bone, blood vessels, and biomaterials with microcomputed tomography. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2003;22:77–83. doi: 10.1109/memb.2003.1256276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapirstein A, Saito H, Texel SJ, Samad TA, O'Leary E, Bonventre JV. Cytosolic phospholipase A2alpha regulates induction of brain cyclooxygenase-2 in a mouse model of inflammation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1774–R1782. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00815.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Ziran N, Goater JJ, Schwarz EM, Puzas JE, Rosier RN, Zuscik M, Drissi H, O'Keefe RJ. Primary murine limb bud mesenchymal cells in long-term culture complete chondrocyte differentiation: tGF-beta delays hypertrophy and PGE2 inhibits terminal differentiation. Bone. 2004;34:809–817. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leber TM, Balkwill FR. Zymography: a single-step staining method for quantitation of proteolytic activity on substrate gels. Anal Biochem. 1997;249:24–28. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochhausen C, Neuland P, Kirkpatrick CJ, Nusing RM, Klaus G. Cyclooxygenases and prostaglandin E2 receptors in growth plate chondrocytes in vitro and in situ–prostaglandin E2 dependent proliferation of growth plate chondrocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R78. doi: 10.1186/ar1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jee WS, Ke HZ, Li XJ. Long-term anabolic effects of prostaglandin-E2 on tibial diaphyseal bone in male rats. Bone Miner. 1991;15:33–55. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(91)90109-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen HR, Svanholm H, Host A. Bone formation induced in an infant by systemic prostaglandin-E2 administration. Acta Orthop Scand. 1988;59:464–466. doi: 10.3109/17453678809149406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keila S, Kelner A, Weinreb M. Systemic prostaglandin E2 increases cancellous bone formation and mass in aging rats and stimulates their bone marrow osteogenic capacity in vivo and in vitro. J Endocrinol. 2001;168:131–139. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1680131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibonga JD, Zhang M, Ritman EL, Turner RT. Restoration of bone mass in the severely osteopenic senescent rat. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:B71–B78. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.2.b71. discussion B79–B84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz Z, Gilley RM, Sylvia VL, Dean DD, Boyan BD. The effect of prostaglandin E2 on costochondral chondrocyte differentiation is mediated by cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate and protein kinase C. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1825–1834. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.4.5919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz Z, Sylvia VL, Curry D, Luna MH, Dean DD, Boyan BD. Arachidonic acid directly mediates the rapid effects of 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 via protein kinase C and indirectly through prostaglandin production in resting zone chondrocytes. Endocrinology. 1999;140:2991–3002. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.7.6801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado E, Schwartz Z, Sylvia VL, Dean DD, Boyan BD. Transforming growth factor-beta1 regulation of growth zone chondrocytes is mediated by multiple interacting pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1590:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvia VL, Schwartz Z, Dean DD, Boyan BD. Transforming growth factor-beta1 regulation of resting zone chondrocytes is mediated by two separate but interacting pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1496:311–324. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, Ashby B. Agonist-induced internalization and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation of the human prostaglandin EP4 receptor. FEBS Lett. 2001;501:156–160. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02640-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, April H, Nwaneshiudu C, Ashby B. Comparison of agonist-induced internalization of the human EP2 and EP4 prostaglandin receptors: role of the carboxyl terminus in EP4 receptor sequestration. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:1279–1286. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.6.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino H, Salvi S, Regan JW. Differential regulation of phosphorylation of the cAMP response element-binding protein after activation of EP2 and EP4 prostanoid receptors by prostaglandin E2. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:251–259. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.011833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino H, Regan JW. EP(4) prostanoid receptor coupling to a pertussis toxin-sensitive inhibitory G protein. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:5–10. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaoka S, Takai T, Yoshida K. Cyclooxygenase-2 and tumor biology. Adv Clin Chem. 2007;43:59–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosslien E. Review: molecular pathology of cyclooxygenase-2 in cancer-induced angiogenesis. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2001;31:325–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MK, Wang H, Peskar BM, Levin E, Itani RM, Sarfeh IJ, Tarnawski AS. Inhibition of angiogenesis by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: insight into mechanisms and implications for cancer growth and ulcer healing. Nat Med. 1999;5:1418–1423. doi: 10.1038/70995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dormond O, Foletti A, Paroz C, Ruegg C. NSAIDs inhibit alpha V beta 3 integrin-mediated and Cdc42/Rac-dependent endothelial-cell spreading, migration and angiogenesis. Nat Med. 2001;7:1041–1047. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SH, Liu CH, Conway R, Han DK, Nithipatikom K, Trifan OC, Lane TF, Hla T. Role of prostaglandin E2-dependent angiogenic switch in cyclooxygenase 2-induced breast cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:591–596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2535911100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao S, Kuwano T, Tsutsumi-Miyahara C, Ueda S, Kimura YN, Hamano S, Sonoda KH, Saijo Y, Nukiwa T, Strieter RM, Ishibashi T, Kuwano M, Ono M. Infiltration of COX-2-expressing macrophages is a prerequisite for IL-1 beta-induced neovascularization and tumor growth. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2979–2991. doi: 10.1172/JCI23298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colleselli D, Bijuklic K, Mosheimer BA, Kahler CM. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 affects endothelial progenitor cell proliferation. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:2933–2941. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Frischer J, Serur A, Huang J, Bae JO, Kornfield ZN, Eljuga L, Shawber CJ, Feirt N, Mansukhani M, Stempak D, Baruchel S, Glade Bender J, Kandel JJ, Yamashiro DJ. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 disrupts tumor vascular mural cell recruitment and survival signaling. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4378–4384. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo R, Zhang X, Young HA, Michael N, Wasserman K, Ma WH, Martins-Green M, Murphy WJ, Oppenheim JJ. Angiogenic effects of prostaglandin E2 are mediated by up-regulation of CXCR4 on human microvascular endothelial cells. Blood. 2003;102:1966–1977. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu TH, Shipley JM, Bergers G, Berger JE, Helms JA, Hanahan D, Shapiro SD, Senior RM, Werb Z. MMP-9/gelatinase B is a key regulator of growth plate angiogenesis and apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell. 1998;93:411–422. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81169-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber HP, Vu TH, Ryan AM, Kowalski J, Werb Z, Ferrara N. VEGF couples hypertrophic cartilage remodeling, ossification and angiogenesis during endochondral bone formation. Nat Med. 1999;5:623–628. doi: 10.1038/9467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colnot C, Thompson Z, Miclau T, Werb Z, Helms JA. Altered fracture repair in the absence of MMP9. Development. 2003;130:4123–4133. doi: 10.1242/dev.00559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau B, Ge PJ, Ohno T, French LC, Thibeault SL. Extracellular matrix gene expression after vocal fold injury in a rabbit model. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117:598–603. doi: 10.1177/000348940811700809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agren MS. Gelatinase activity during wound healing. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:634–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb04974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson ML, Garcia-Morales C, Abu-Elmagd M, Wheeler GN. Three matrix metalloproteinases are required in vivo for macrophage migration during embryonic development. Mech Dev. 2008;125:1059–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JY, Bourguignon LY, Adams CM, Peyrollier K, Zhang H, Fandel T, Cun CL, Werb Z, Noble-Haeusslein LJ. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 facilitates glial scar formation in the injured spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13467–13477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2287-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuel JA, Gawronska-Kozak B. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) is upregulated during scarless wound healing in athymic nude mice. Matrix Biol. 2006;25:505–514. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.