Abstract

The reverse transcriptase (RT) of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) catalyzes a series of reactions to convert single-stranded viral RNA into double-stranded DNA for host cell integration. This process requires a variety of enzymatic activities, including DNA polymerization, RNA cleavage, strand transfer, and strand displacement synthesis. Here, we use single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer to probe the interactions between RT and nucleic-acid substrates in real time. RT was observed to slide on nucleic-acid duplexes, rapidly shuttling between opposite termini of the duplex. Upon reaching DNA 3' terminus, RT can spontaneously flip into a polymerization orientation. Sliding kinetics were regulated by cognate nucleotides and anti-HIV drugs, which stabilized and destabilized the polymerization mode, respectively. These long-range translocation activities facilitate multiple stages of the reverse transcription pathway, including normal DNA polymerization and strand displacement synthesis.

Retroviral reverse transcriptase (RT) is a multi-functional enzyme that catalyzes conversion of the single-stranded viral RNA genome into integration-competent double-stranded DNA. RT possesses several distinct activities, including DNA- and RNA-dependent DNA synthesis, DNA-directed RNA cleavage, strand transfer, and strand displacement synthesis, all of which are required to complete the reverse transcription cycle (Fig. S1) (1, 2). The enzyme first uses viral RNA as the template to synthesize minus-strand DNA (3, 4), and the resulting DNA/RNA hybrid is then cleaved by the RNase H activity of RT to produce short RNA fragments hybridized to nascent DNA (5, 6). Specific RNA fragments, known as the polypurine tracts (PPTs), serve as primers for synthesis of plus-strand DNA from the minus-strand DNA template (7-9). Secondary structures present in the viral RNA genome, as well as the non-template strands hybridized to the DNA template, require RT to perform strand displacement synthesis during both minus- and plus-strand DNA synthesis (10-16).

As a major target for anti-HIV therapy, RT has been the subject of extensive research. Crystal structures, biochemical assays and single-molecule analyses have suggested different modes of interaction between RT and nucleic acid substrates, providing snapshots of the nucleoprotein complexes that illuminate the functional mechanism of RT [e.g. (17-25)]. Nevertheless, how the enzyme-substrate complex acquires specific functional configurations and switches between different functional modes remains unclear. For example, how does RT efficiently locate the 3' terminus of nascent DNA on a long duplex substrate to initiate DNA polymerization? This question is particularly important for a low-processivity polymerase such as RT, which must frequently locate the polymerization site following dissociation (10, 26). Perhaps even more puzzling is how the dissociated RT locates the polymerization site during strand displacement synthesis, considering that the primer terminus may itself be displaced from the template by the competing non-template strand. Also, RT cleaves at many different sites within a DNA/RNA hybrid, but how it accesses these sites remains incompletely understood (21, 22). A dynamic visualization of RT interacting with different substrates will help us address these questions and gain a more complete understanding of its function.

In this work, we used fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) (27, 28) to monitor in real time the action of individual HIV-1 RT molecules and their interactions with various nucleic acid substrates. We specifically labeled RT with the FRET donor dye Cy3 at either the RNase H domain (H-labeled) or the fingers domain (F-labeled) of its catalytically active p66 subunit (Fig. S2A) (2, 29, 30). An E478Q mutation was introduced to eliminate RNase H activity (31) and prevent degradation of the nucleic acid substrates during experiments. Nucleic acid substrates were labeled with the FRET acceptor dye Cy5 at various sites, specifically immobilized on a quartz surface, and immersed in a solution containing Cy3-labeled RT (Fig. S2B) (2). Fluorescence from individual RT-substrate complexes was monitored with a total-internal-reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscope using an alternating laser excitation scheme (32). The observed FRET value allowed the binding configuration of the enzyme to be determined (Fig. S2C) (2). Control experiments showed that neither dye labeling nor surface immobilization significantly affected the enzyme activity (Fig. S3) and that photophysical properties of the FRET dyes did not change appreciably when placed in proximity to the enzyme (Fig. S4) (2).

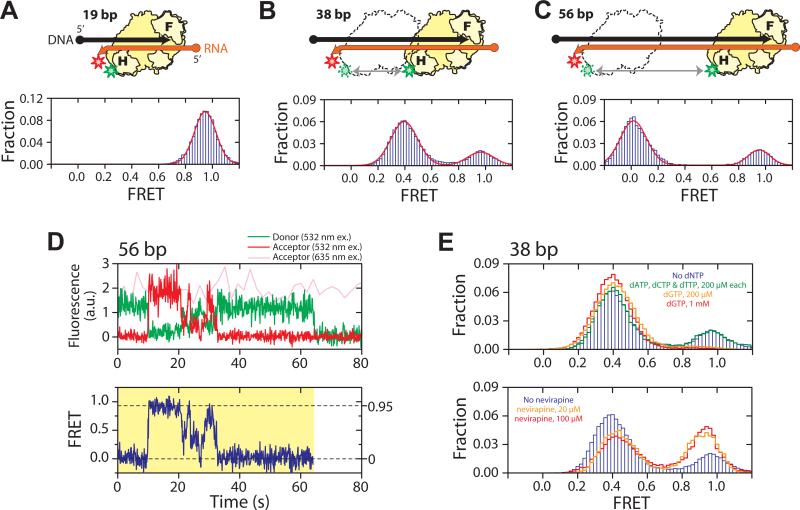

To mimic substrates encountered by RT during minus-strand synthesis, we constructed a series of hybrid structures of various lengths, each consisting of a DNA primer and an RNA template with Cy5 attached to one of two sites: (i) near the 3′ end of the RNA template, which we define as the “back end” of the hybrid (“back-labeled”, Figs. 1A-C); or (ii) near the 5′ end of the RNA template and 3′ end of the DNA primer, which we define as the “front end” (“front-labeled”, Figs. S5B, C) (2). On a 19 base pair (bp) hybrid, a length chosen to approximate its footprint on nucleic acid duplexes (17-20, 31, 33), RT bound in only one configuration: binding of H-labeled RT to the back-labeled substrate yielded uniformly high FRET values (centered at 0.95) (Fig. 1A), indicating that RT bound with its RNase H domain close to the back end of the hybrid. Considering that the RNase H and polymerase active sites are at opposite ends of the substrate binding cleft of RT, this configuration places the polymerase active site of the RT over the 3′ terminus of the DNA primer, consistent with the polymerization-competent binding mode observed in crystal structures (17, 18).

Fig. 1.

RT slides on nucleic acid substrates. (A - C) H-labeled RT (yellow) bound to a 19 bp (A), 38 bp (B), and 56 bp (C) back-labeled DNA (black) / RNA (orange) hybrid. F and H on the enzyme represent the fingers and RNase H domains, and circle and arrow on the nucleic acid strands represent 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. Green and red stars indicate Cy3 and Cy5 dyes, respectively. The FRET histograms (blue bars) were fit with a single (A) or double (B, C) Gaussian peaks (red line). (D) Representative fluorescence (upper panel) and FRET (lower panel) time traces of RT bound to a 56 bp DNA/RNA hybrid at 12 °C, showing gradual transitions between the 0 and 0.95 FRET states and preferred intermediates near FRET ∼ 0.3 − 0.5. The time resolution is 10 Hz. The green and red traces represent donor and acceptor fluorescence under 532 nm excitation and the pink trace represents acceptor fluorescence under 635 nm excitation. The yellow shade marks a single RT binding event. (E) Effects of nucleotides and nevirapine on sliding. (Upper panel) FRET histograms of RT bound to the 38 bp DNA/RNA hybrid in the absence of nucleotides (blue bars), in the presence of the cognate dGTP (orange and red lines), or non-cognate nucleotides (green line). The DNA primer was chain-terminated to prevent elongation. (Lower panel) FRET histograms in the absence (blue bars) and presence of nevirapine (orange and red lines).

In contrast, two distinct binding modes were observed on longer DNA/RNA hybrids. H-labeled RT bound to back-labeled 38 bp hybrid yielded two FRET peaks centered at 0.95 and 0.39, respectively (Fig. 1B). The FRET value of 0.39 is quantitatively consistent with RT binding in polymerization competent mode, in which the polymerase active site is located over the primer terminus at the front end of the hybrid, placing the Cy3 dye ∼19 bp away from the Cy5 label. The high-FRET peak at 0.95 indicates an additional binding mode in which the RNase H domain is located near the back end of the hybrid, which apparently cannot support polymerase activity. The equilibrium constant between the front- and back-end binding states was 3.3:1. Moving the biotin from the 5' end of the DNA primer (i.e. near the back end of the hybrid) to the 5' end of the RNA template (i.e. near the front end) resulted in a nearly identical equilibrium constant (3.1:1), again suggesting a minimal effect of surface immobilization. These two binding modes at the front- and back-end of the hybrid were further confirmed by two additional FRET labeling schemes in which F-labeled or H-labeled RT was added to the front-labeled substrate (Fig. S5) (2). The two end-binding states also predict further separation of the two FRET peaks as the length of the hybridized region increases, which was experimentally confirmed with a 56 bp hybrid. Binding of H-labeled RT to the back-labeled 56 bp hybrid produced two FRET peaks centered at 0 and 0.95, also with a ∼3:1 partition ratio (Fig. 1C).

Taken together, these results indicate that the enzyme can stably bind either to the front end of the hybrid poised for DNA extension, or to the back end placing the RNase H domain close to the 3′ end of the RNA template. The front-end binding state of RT should also support RNase H activity. The two binding modes were independent of hybrid sequence, the nature of the hybrid termini, i.e. whether they feature recessed DNA or RNA (Fig. S6), or whether the RNase H-inactivating E478Q mutation was introduced (Fig. S5) (2). To further test whether sliding was a general activity of RT, we exchanged the RNA template in the DNA/RNA hybrid for a DNA template to emulate plus-strand DNA synthesis. RT was again observed to slide between the termini of the duplex DNA, although the transition rates between the two ends were different from those observed on the DNA/RNA hybrid (Fig. S7) (2).

The FRET time traces of individual RT molecules showed repeated transitions between the front- and back-end bound states within a single binding event (Fig. 1D), suggesting shuttling between the two ends of the hybrid without dissociation. The FRET transitions between the two end states were not instantaneous, but rather gradual with preferred intermediate states in the middle of the hybrid (Figs. 1D, S8A, S8B) (2). Shuttling motion sped up as the temperature was raised (Fig. S8C), but did not require nucleotide hydrolysis, suggesting that the movement is a thermally driven diffusion process. RT was previously observed to cleave RNA at multiple positions within a DNA/RNA hybrid (5, 21, 22), in a manner consistent with the end-binding states and sliding intermediates observed here suggesting that sliding may provide a mechanism for RT to rapidly access these cleavage sites.

It is remarkable that a polymerase could frequently slide away from the polymerization site. To explore what structural rearrangements within the enzyme may be required for this action, we tested the effects of small molecule ligands on sliding kinetics. Binding of a cognate nucleotide is expected to cause the fingers and thumb domains of RT to form a tighter grip around the primer terminus (34) and stabilize the polymerization state. To test the effect of nucleotide binding, we again used H-labeled RT and back-labeled 38 bp DNA/RNA hybrid, but with 3′ dideoxynucleoside-terminated DNA primer to prevent DNA synthesis. Addition of dGTP, the next cognate nucleotide, significantly stabilized the low FRET front-end bound state (Fig. 1E), further supporting the notion that the front-end bound state reflects RT binding in the polymerization-competent mode. Kinetically, addition of 1 mM dGTP slowed down the rate constant of front to back transitions (kfront→back) by 12 fold without substantially affecting the reverse rate constant kback→front (Fig. S7C) (2). In contrast, addition of mismatched nucleotides (dATP, dCTP, and dTTP) did not significantly affect the transition kinetics (Fig. 1E). Another small molecule ligand tested was the non-nucleoside RT inhibitor (NNRTI), one of the major classes of anti-HIV drugs that inhibit DNA synthesis (30, 35). We measured the sliding dynamics of RT in the presence of nevirapine, a representative NNRTI. Interestingly, the effects of the drug were opposite to those of the cognate dNTP: addition of nevirapine destabilized the front-end bound state of the enzyme (Fig. 1E) by increasing kfront→back without significantly altering kback→front (Fig. S8C) (2). Structurally, NNRTI and cognate dNTP have opposite effects on the conformation of RT near the polymerase active site (34, 35): while nucleotide binding tightens the clamp of the fingers and thumb domains around the substrate, binding of NNRTI loosens the clamp. Hence, our data suggest that relaxation of the fingers-thumb grip is likely required for RT to escape the polymerization site. Our observation that NNRTI promotes enzyme escape from the polymerization site also suggests an inhibitory mechanism for this class of drugs, and explains why the inhibitory effect of NNRTI is stronger on long DNA synthesis than on short DNA synthesis (36).

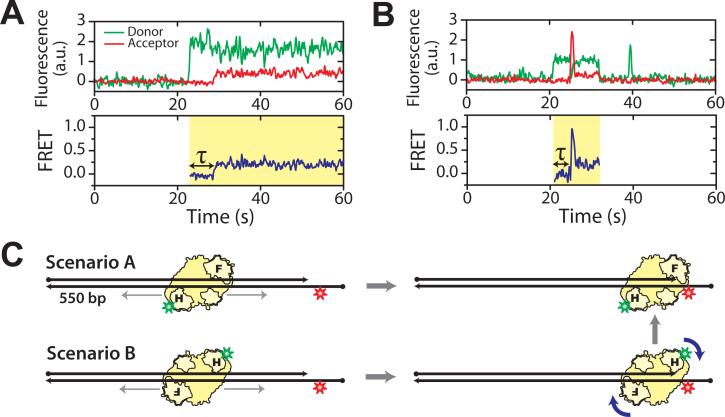

Next, we probed potential functional roles of RT sliding on reverse transcription. Compared to cellular DNA polymerases, RT exhibits poor processivity, typically dissociating from the substrate after synthesizing only a few to a few hundred nucleotides (10, 26), despite a ∼10 kb-long HIV genome (37). RT thus frequently encounters the challenge of having to locate the nascent DNA terminus to continue DNA synthesis. The ability of RT to slide on duplexes suggests an interesting mechanism of enzyme targeting by one-dimensional search, a mechanism that has been proposed for target searching by transcription factors, RNA polymerase and DNA repair enzyme (38-42). To test this possibility, we added H-labeled RT to a ∼550 bp front-labeled DNA duplex (Fig. 2). Were RT to bind directly to the duplex front end, we would expect a FRET value of 0.3 immediately upon binding, corresponding to the ∼19 bp distance expected between Cy3 and Cy5. Instead, we found that the majority of the binding events initiated with a FRET value of 0, reaching 0.3 only after a finite time delay (Figs. 2A, S9). This observation indicates that the enzyme first bound to the DNA outside the polymerization site and subsequently moved to the primer terminus where polymerization takes place (Fig. 2C). Such a binding procedure will likely increase the polymerization target searching efficiency on long duplexes where the primer terminus constitutes only a tiny fraction of the duplex substrate. However, if the enzyme can indeed bind in the middle of a duplex, the lack of directional cues may also lead to binding in the “wrong” orientation, such that the RNase H domain is poised closer to 3' terminus of the primer than the polymerase domain (Fig. 2C). In this case, even after sliding to the front end, RT would not be properly positioned for DNA synthesis. This type of binding was indeed observed frequently, as indicated by a high FRET state ∼ 0.9 following the initial 0 FRET state (Fig. 2B). Remarkably, the high FRET state converted rapidly into the 0.3 FRET state in situ without dissociation (Fig. 2B), indicating that the enzyme flipped into the polymerization-competent orientation. The ability of RT to flip to the polymerization orientation once reaching the primer terminus without dissociation may further increase its target searching efficiency. Our data does not exclude a possibility that the enzyme may also flip in the middle of the duplex, though such flipping events should not lead to a net increase of target searching efficiency.

Fig. 2.

Sliding of RT facilitates polymerization site targeting. H-labeled RT was added to a ∼550 bp DNA duplex with Cy5 attached near the front end. Binding of RT to the polymerization site at the duplex front end is expected to give a FRET value of 0.3. (A) Donor and acceptor fluorescence and corresponding FRET time traces of a typical binding event show a time delay (τ) between binding of RT and placing of RT at the polymerization site. (B) A binding event showing a transient 0.9 FRET state between the 0 and 0.3 FRET states, suggesting that RT arrived at the front end in an orientation that placed the RNase H domain close to the primer terminus, and subsequently flipped to the polymerization orientation. The time resolution of the traces is 10Hz. Cy5 fluorescence under direct 635 nm excitation (omitted for clarity) indicates that an active Cy5 is present during the whole detection time. Yellow shades in the FRET time traces mark individual RT binding events. The histogram of the time delay τ is shown in Fig. S9. (C) Schematic depiction of the two primer terminus search scenarios as suggested by traces in (A) and (B).

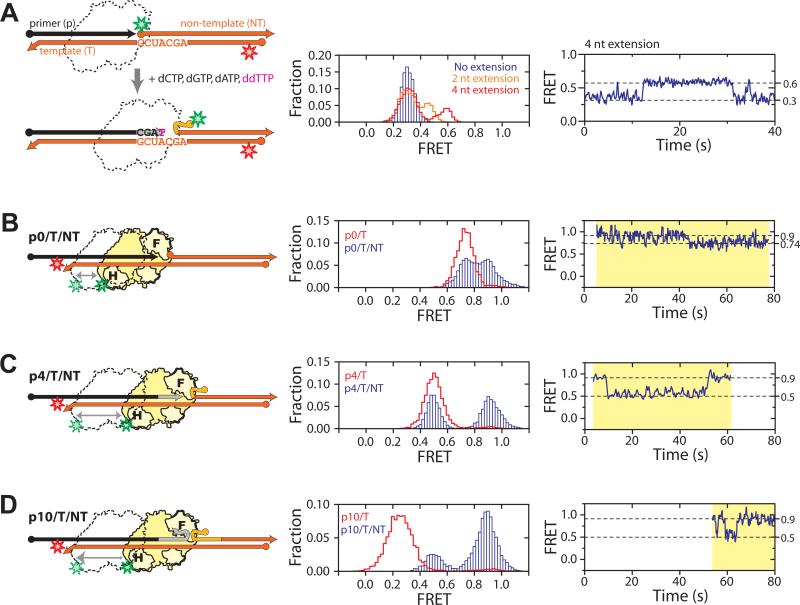

Hairpins and long duplexes present on the template strand during DNA synthesis require the polymerization machinery to perform strand displacement synthesis. Polymerization site targeting on these substrates may be even more challenging since after enzyme dissociation, these template secondary structures could displace the nascent primer terminus to occlude the polymerization site. This is especially problematic in the case of intra-strand RNA displacement during minus-strand synthesis, as duplex RNA is more stable than a DNA/RNA hybrid (43, 44). To probe the structural dynamics of substrates encountered during RNA strand displacement synthesis, we designed a series of FRET-labeled triple-stranded substrates, each consisting of an RNA template (T) to which a complementary DNA primer (p) and RNA non-template strand (NT) were simultaneously hybridized, with the Cy3 and Cy5 dyes flanking the T/NT duplex region (Fig. 3A). We use the notation pX/T/NT to represent a substrate whose primer has been extended by X nucleotides. As expected, the FRET distributions for substrates with all X values displayed a peak at 0.3, identical to that observed for the non-extended p0/T/NT substrate (Fig. S10), indicating that the T/NT duplex was fully annealed and that the extended DNA primers were not able to displace the NT RNA.

Fig. 3.

RNA strand displacement synthesis. (A) Substrate structural dynamics during strand displacement synthesis. RT and nucleotides were added to Cy3/Cy5 doubly labeled p0/T/NT substrate to initiate synthesis. Overlapping sequence within the p and NT strands are colored in light grey and light orange, respectively. The corresponding FRET histograms are shown in the middle panel. Blue bars represent the FRET distribution in the presence of RT but absence of nucleotides. The orange line indicates the distribution in the presence of dCTP, ddGTP, dATP, and dTTP, and the red line indicates the distribution in the presence of dCTP, dGTP, dATP, and ddTTP, allowing a 2- and 4-nucleotide extension, respectively. A representative FRET time trace for the latter case is shown in the right panel. (B-E) Sliding of RT during RNA strand displacement synthesis. (B) H-labeled RT bound to back-labeled p0/T/NT. The corresponding FRET histogram (middle panel, blue bars) and representative time trace (right panel) show dynamic transitions two FRET states (0.74 and 0.9). Overlaid in the FRET histogram was the FRET distribution of RT bound to the p0/T substrate lacking the NT strand (red line). (C, D) As above except that p0/T/NT is replaced by p4/T/NT (C) or p10/T/NT (D) to mimic the extended substrates encountered during RNA displacement synthesis. The corresponding FRET histograms (middle panel, blue bars) and time traces (right panel) show dynamic transitions between FRET states of 0.5 and 0.9. Overlaid in red lines are the FRET distributions of RT bound to the corresponding pX/T duplex without the NT strand. Yellow shades in the right panels mark individual RT binding events, all of which started with FRET = 0.9, indicating initial binding to the back end of the pX/T region. Time resolutions of the traces are 10 Hz in A, B, D and 5 Hz in C. All measurements were done in the presence of dNTPs and the primer 3′ terminus was dideoxynucleoside terminated to prevent elongation.

We then added RT and dNTPs to the p0/T/NT substrate to monitor substrate dynamics during displacement synthesis. In the absence of dNTP, a single FRET peak centered at 0.3 was again observed (Fig. 3A). After addition of dNTP to initiate primer extension and selected dideoxynucleoside triphosphate (ddNTP) to terminate synthesis at specific positions, FRET was observed to increase due to unwinding of the T/NT duplex. The presence of dCTP, ddGTP, dATP, and dTTP supported a two-nucleotide addition, producing a higher FRET peak at 0.45 (Fig. 3A). This higher FRET peak further increased to 0.6 in the presence of dCTP, dGTP, dATP, and ddTTP, which allowed a four-nucleotide extension (Fig. 3A). The FRET distribution agreed quantitatively with that observed for the pre-assembled, chain-terminated p4/T/NT substrate in the presence of RT and dNTPs (Fig. S11) (2), confirming successful primer extension. FRET time traces of individual molecules showed repetitive transitions between the 0.6 and 0.3 FRET states (Fig. 3A), suggesting frequent re-annealing of the T and NT strands.

One possible cause for T/NT re-annealing is sliding of RT to the back end of the p/T hybrid, leaving its front end unbound. To test this experimentally, we added Cy3-labeled RT and dNTPs to Cy5-labeled pX/T/NT substrates, the primers of which were chain-terminated to prevent extension (Figs. 3B-D). Indeed, transitions between a high and a relatively low FRET state were observed. The high FRET state (0.9) indicates proximity of RT to the back end of the p/T hybrid. The lower FRET states (0.74 for p0/T/NT and 0.5 for p4/T/NT) quantitatively agree with those observed for the p0/T and p4/T hybrids lacking the NT strand (Figs. 3B, C), to which RT should predominantly bind at the front end in the presence of dNTPs. These results indicate that RT shuttles between the polymerization site and the back end of the substrate even during displacement synthesis.

In the absence of enzyme, a stable T/NT RNA duplex was formed (Fig. S10) and no spontaneous annealing of the pX/T hybrid was observed in the FRET time traces. The low processivity of RT poses another question: How would the enzyme, after dissociation, locate the polymerization site (i.e. the front end of the primer/template hybrid) again if such a structure is rarely formed? The answer can be found in the FRET traces: The vast majority (∼90%) of the binding events on the pX/T/NT substrates started at the back-end with high FRET, with RT subsequently sliding forward to assume the front-end binding state with relatively low FRET (Fig. 3C, right panel). These observations suggest that sliding allows the enzyme to kinetically access the disrupted polymerization site and assist primer-template annealing, thereby facilitating RNA strand displacement synthesis.

Interestingly, on a substrate with a longer primer extension (p10/T/NT), FRET was also observed to switch between the same 0.9 and 0.5 states as observed for the p4/T/NT substrate (Fig. 3D). Had the primer/template hybrid fully annealed, binding of RT to the front-end of the hybridized region would yield FRET values significantly lower than 0.5, as observed for the p10/T substrates lacking the NT strand (Fig. 3D). Similar results were found for the p5/T/NT substrate. These data indicate that RT was not able to slide all the way to the front end of the primer once the overlap between the p and NT strands exceeded 4 nucleotides. Moreover, the enzyme predominantly remained at the back end of the substrate. We thus expect the efficiency of strand displacement synthesis to drop accordingly. This was directly confirmed by an ensemble primer extension assay, which revealed that primer extension primarily terminated after adding 5 nucleotides through RNA strand displacement synthesis (Fig. S12A) (2). The exact termination sites were sequence-dependent, consistent with previous observations (16).

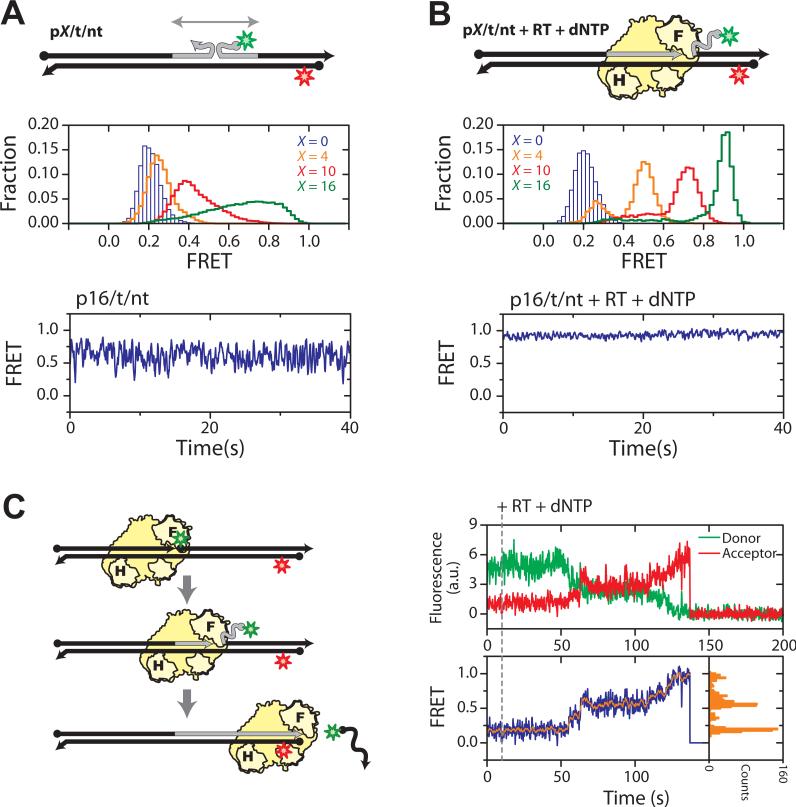

The energetic difference between the pX/T and T/NT duplexes observed during RNA strand displacement synthesis does not exist in DNA strand displacement synthesis, as all strands involved in the latter case are DNA. To examine substrate dynamics during DNA strand displacement synthesis, all DNA primer/template/non-template substrates (defined as pX/t/nt) were doubly labeled with Cy3 and Cy5 (Fig. 4A). In contrast to the pX/T/NT counterparts, the FRET distributions were substantially broader for non-zero primer extension (X = 4, 10, 16), and rapid FRET fluctuations were observed in single-molecule traces (Fig. 4A). These observations suggest frequent exchanges between the primer and non-template strands for base-pairing with the template. Following addition of RT and dNTPs to the substrates (chain-terminated to prevent primer extension), the FRET distribution predominantly assumed a high FRET value that consistently increased with X (Fig. 4B), suggesting that RT reached the front end of the p/t duplex and unwound the t/nt duplex. Even in the case of DNA displacement synthesis, the primer was rarely fully annealed to the template in the absence of a bound RT. It is likely that RT is also targeted to the polymerization site by first binding to the intact part of the primer/template duplex and subsequently sliding forward to unwind the non-template strand and anneal the primer (23). As there is no significant energy penalty for exchanging DNA base pairs, RT was thus able to access the primer terminus regardless of the length of the primer extension (Fig. 4B), consistent with RT's ability to perform displacement synthesis through long DNA duplexes (12). When RT and dNTPs were added to the non-terminated p0/t/nt substrate to support synthesis, an increase in FRET was observed as the nt strand was displaced (Fig. 4C). Once the FRET donor-labeled nt strand was fully displaced, a sudden drop in the total fluorescence signal reflected completion of the reaction (Fig. 4C). Rapid and complete DNA strand displacement synthesis was observed for nearly all molecules (Fig. S12) (2). Frequent pausing was also observed during synthesis, indicated by plateaus in the single-molecule FRET trace (Fig. 4C). The origin of these kinetic pausing events and their relation to the preferred synthesis termination sites (23, 45) will be a subject of future investigation.

Fig. 4.

DNA strand displacement synthesis. (A) Structural dynamics of the pX/t/nt substrates (X = 0, 4, 10, and 16) consisting of all DNA strands. The corresponding FRET histograms are shown in the middle panel and a representative FRET time trace (X = 16) in the bottom panel. (B) As in A, but in the presence of RT and dNTPs. The primers were terminated with a dideoxynucleoside to prevent elongation. (C) Single-molecule detection of DNA displacement synthesis. RT and dNTPs were added to the p0/t/nt substrate to initiate DNA synthesis in situ. FRET gradually increased as reaction progressed, due to the unzipping of the nt strand. Completion of the reaction was marked by the abrupt loss of the fluorescence signal, due to dissociation of the donor labeled nt strand. Plateaus were observed in the donor/acceptor fluorescence traces (upper panel) and the FRET trace (blue trace in the lower left panel), indicating pausing events during synthesis. As a corollary, distinct peaks were observed in the histogram (lower right panel) constructed from the FRET trace smoothed by 5-point average (orange trace in lower left panel). Time resolutions are 16 Hz in A and B, and 10 Hz in C.

HIV-1 RT thus appears to be a highly dynamic enzyme that can spontaneously slide over long distances on DNA/RNA and DNA/DNA duplex structures, facilitating multiple phases of reverse transcription, including targeting RT to the primer terminus for DNA polymerization, allowing the enzyme to rapidly access multiple sites within an RNA/DNA hybrid during viral RNA degradation, and displacing the non-template strand and annealing primer terminus during displacement synthesis. The dynamic flexibility further extends into orientational conformations allowing the enzyme to flip between opposite binding orientations that support different activities (21, 25). Flipping and sliding can be combined in a complex series of enzyme movements to enhance its efficacy: RT molecules originally bound in the opposite orientation were observed to spontaneously flip into the polymerization orientation after sliding to the primer terminus. It is remarkable that an enzyme could have such large-scale orientational and translational dynamics. This type of dynamic flexibility may be a general design principle for multi-functional enzymes like HIV RT, helping them to rapidly access different binding configurations required to accomplish different functions.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Telesnitsky A, Goff SP. In: Retroviruses. Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE, editors. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 121–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Supporting material is available on Science online.

- 3.Baltimore D. Nature. 1970;226:1209. doi: 10.1038/2261209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temin HM, Mizutani S. Nature. 1970;226:1211. doi: 10.1038/2261211a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leis JP, Berkower I, Hurwitz J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973;70:466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.2.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen J, Schulze T, Mellert W, Moelling K. Embo J. 1988;7:239. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith JK, Cywinski A, Taylor JM. J Virol. 1984;49:200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.49.1.200-204.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omer CA, Resnick R, Faras AJ. J Virol. 1984;50:465. doi: 10.1128/jvi.50.2.465-470.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finston WI, Champoux JJ. J Virol. 1984;51:26. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.1.26-33.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huber HE, McCoy JM, Seehra JS, Richardson CC. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hottiger M, Podust VN, Thimmig RL, McHenry C, Hubscher U. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whiting SH, Champoux JJ. J Virol. 1994;68:4747. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4747-4758.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuentes GM, Fay PJ, Bambara RA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1719. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.9.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suo Z, Johnson KA. Biochemistry. 1997;36:12459. doi: 10.1021/bi971217h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelleher CD, Champoux JJ. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanciault C, Champoux JJ. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobo-Molina A, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarafianos SG, et al. Embo J. 2001;20:1449. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarafianos SG, et al. Embo J. 2002;21:6614. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Metzger W, Hermann T, Schatz O, Le Grice SF, Heumann H. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:5909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeStefano JJ, Mallaber LM, Fay PJ, Bambara RA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4330. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.18.4330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wisniewski M, Balakrishnan M, Palaniappan C, Fay PJ, Bambara RA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007381200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winshell J, Paulson BA, Buelow BD, Champoux JJ. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothwell PJ, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0434003100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbondanzieri EA, et al. Nature. 2008;453:184. doi: 10.1038/nature06941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams KJ, Loeb LA, Fry M. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stryer L, Haugland RP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1967;58:719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.2.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ha T, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hostomsky Z, Hostomska Z, Fu TB, Taylor J. J Virol. 1992;66:3179. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.3179-3182.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohlstaedt LA, Wang J, Friedman JM, Rice PA, Steitz TA. Science. 1992;256:1783. doi: 10.1126/science.1377403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rausch JW, Sathyanarayana BK, Bona MK, Le Grice SF. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909808199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kapanidis AN, et al. Science. 2006;314:1144. doi: 10.1126/science.1131399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gotte M, Maier G, Gross HJ, Heumann H. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang H, Chopra R, Verdine GL, Harrison SC. Science. 1998;282:1669. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ren J, et al. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:293. doi: 10.1038/nsb0495-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quan Y, Liang C, Inouye P, Wainberg MA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5692. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.24.5692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ratner L, et al. Nature. 1985;313:277. doi: 10.1038/313277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.von Hippel PH, Berg OG. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kabata H, et al. Science. 1993;262:1561. doi: 10.1126/science.8248804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guthold M, et al. Biophys J. 1999;77:2284. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77067-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blainey PC, van Oijen AM, Banerjee A, Verdine GL, Xie XS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509723103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elf J, Li GW, Xie XS. Science. 2007;316:1191. doi: 10.1126/science.1141967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall KB, McLaughlin LW. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10606. doi: 10.1021/bi00108a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugimoto N, Nakano S, Yoneyama M, Honda K. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4501. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klarmann GJ, Schauber CA, Preston BD. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.This work is supported in part by NIH (GM 068518, to X.Z.) and the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, NCI (to S.F.J.L.G.). X.Z. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. E.A.A. is a Jane Coffin Childs postdoctoral fellow. Nevirapine was provided through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program of the National Institutes of Health.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.