Abstract

The Hibiscus trionum flower is distinctly patterned, with white petals each with a patch of red pigment at the base, producing a ‘bulls-eye’ pattern on the whole flower. The red pigmented patches are also iridescent, due to the presence of a series of overlying cuticular striations that act as a diffraction grating. We have previously reported that scanning electron microscopy revealed a sharply defined difference between the surface structure overlying the pigmented patch and that over the rest of the petal, with the diffraction grating only present over the pigmented region. Here we show that differences in petal surface structure overlie differences in pigment color in three other species, in a range of different patterns. Floral patterns have previously been shown to be advantageous in pollinator attraction, and we discuss whether emphasis of pigment patterns by structural color may increase floral recognition by pollinators.

Key words: iridescence, structural color, diffraction grating, ultraviolet, floral characteristics, pollination

The primary function of many floral traits appears to be to ensure that flowers are highly visible, recognizable and attractive to animal pollinators. One floral trait that has been shown to increase pollinator visitation to a flower is that of contrasting color patterns.1–10 These patterns can act as guides to pollinators to aid foraging by highlighting the location of nutritional rewards, or can increase visibility by using strongly contrasting colors.1–10 Patterns can occur in the range of wavelengths visible to the human eye, but are also common in the UV (ultraviolet) region of the spectrum.11 Such UV patterns are invisible to humans but visible to many pollinating insects such as bumblebees, whose visual spectrum extends into the near UV region.1

Hibiscus trionum (also known by the common names of ‘flower-of-an-hour’ and ‘modesty’ due to its very short flowering time) produces flowers with a distinct ‘bulls-eye’ pattern (Fig. 1A). The majority of this radially symmetrical (actinomorphic) flower is white, but it has a dark purple center. This dark center is due to a region of purple pigmentation produced at the base of each petal. However, this pigmented region is particularly eye-catching due to the iridescent luster that overlies it. This luster does not extend into the rest of the white colored petal. Analysis of the surface structure of this flower by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) showed a distinct difference in surface structure between the two regions (Fig. 1B). While the white region of the petal, in common with around 79% of all other flowers, has an epidermis composed of conical cells,12 the epidermis over the pigmented region is instead composed of flat (elongated) cells covered by a series of regular parallel striations. We have shown that these striations act as a diffraction grating, producing the visible iridescence.13 Iridescence is the change of hue in the color of a surface according to the angle from which it is being observed. This physical phenomenon results from periodical structured material surfaces or interfaces and can not be caused by pigments alone.

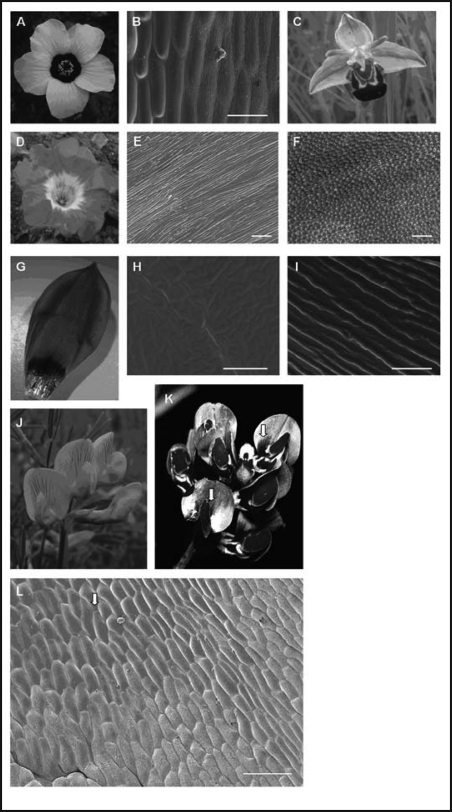

Figure 1.

Photographic floral images (both in visible and UV light) and corresponding scanning electron micrographs. (A and B) Hibiscus trionum flower showing ‘bulls-eye’ pattern. (B) SEM of Hibiscus trionum petal image showing the boundary region (B, scale bar = 50 µm) between the pigmented (striated) region and the white (conical) on the petal. (C) Ophrys apifera flower. (D–F) Nolana paradoxa flowers. (E) striated center white region (E, scale bar = 20 µm). (F) The outer blue region with conical cells (F, scale bar = 100 µm). (G–I) Tulipa humilis petal. (H) The dark inner center with no cuticular striations (H, scale bar = 10 µm). (I) the rest of the petal which has ordered striations (I, scale bar = 5 µm). (J–L) Lathyrus pratensis. (J) Lathyrus pratensis flowers in visible light. (K) Lathyrus pratensis flowers showing UV reflection. The nectar guides at the base of the flag petal are indicated with arrows. (L) SEM of flag showing unstriated region corresponding to nectar guides (base of flag indicted by arrow) (L, scale bar = 100 µm).

UV-vis spectroscopy measurements suggest that the petal surface of H. trionum, displaying elongated flat cells that are overlaid with continuous, periodically spaced striations, shows enhanced reflectance in the UV compared to non structured surfaces.13

Bulls-Eye Patterns

The bulls-eye image has been shown to increase the attractiveness of a flower from a distance, and may also help pollinators orientate themselves on the flower shortly before and after they have landed.2 The pigment bulls-eye pattern in H. trionum is overlaid by a structural bulls-eye pattern. A similar, although in each case slightly different, situation is found in Nolana paradoxa and Tulipa humilis flowers. N. paradoxa, like H. trionum, produces radially symmetrical flowers, but in N. paradoxa the base of the petal is white while the rest of the petal is blue (Fig. 1D). As in H. trionum, the base of the petals has a flat-celled heavily striated surface that, when replicated in transparent, colorless epoxy13 produces iridescence that is visible to the human eye (Fig. 1E), while the rest of the petal is instead covered in conical cells (Fig. 1F). In direct contrast, T. humilis, which has flowers with a dark black center against a pink background, develops striations over the whole tepal except for the central bulls-eye (Fig. 1G–I).

Nectar Guides

Nectar guides have also been shown to increase the attractiveness of flowers to their pollinators, by helping to increase the efficiency with which pollinators can forage. These nectar guides are often found to contrast with the rest of the flower by absorbing strongly in the UV.11 This is certainly the case in Lathyrus pratensis, where the flower appears yellow to human eyes, with black nectar guides that extend over the upper and middle part of the flag (Fig. 1J). However, with a UV sensitive camera, alternative, UV absorbing nectar guides which do not reach the base of the flag and do not correspond with the black pigment nectar guides are visible at the base of the flag of the flower (Fig 1K, indicated by arrows). As with the bulls-eye pattern of H. trionum, N. paradoxa and T. humilis, the pattern of the UV nectar guides can be seen on the surface structure of the petal. Over the majority of the UV-reflecting flag lie ordered striations similar to those found in H. trionum. Over the UV-absorbing nectar guides these striations are missing (Fig. 1L, base of flag indicated by arrow). To what extent the UV absorbing nectar guides in L. pratensis are caused by differences in surface structure or by the interplay of surface structure and underlying pigment is still to be determined.

Other Patterns

Many species of Ophrys orchids have been reported to have an iridescent patch, the speculum, on the elaborate labellum of the flower (Fig. 1C).14 These orchids use sexual deception of male wasps and solitary bees as their mechanism of pollination, and the shape and iridescence of the speculum is thought to mimic the closed wings of the female.

What are the Advantages of Floral Iridescence?

What would be the evolutionary advantage of producing structural colors when plants already have such a diverse repertoire of pigments available to them? In the case of Ophrys, the advantage appears straight forward. Iridescence can only be produced through structural mechanisms, not pigment-based ones. The floral iridescence mimics the iridescence displayed by insect wings, and increases the extent to which the Ophrys flowers act as convincing mimics. Similar mimicry may also be important in other flower-pollinator relationships. One potential area of interest is that many pollinating animals are themselves iridescent.

Iridescence on flowers that do not rely on mimicry for pollination may have a range of other advantages. One potential advantage is that the iridescent color is directional. Floral patterns have already been shown to help pollinators orientate themselves on flowers, and, in the same way that pilots use landing lights to land planes, insects could use the directionality of iridescent color to forage more efficiently.

It has previously been shown in both birds and butterflies that structural color can enhance pigment color either by an additive or a contrast effect, both in the human-visible and UV wavelengths.15–17 The combination of both structural and pigment can produce uniquely enhanced colors.18 As the attractive nature of the floral patterns that we have been considering relies on the color contrast between the two underlying pigments, an overlying surface that highlights or enhances the difference could increase the attractiveness of the whole flower.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Bjørn Rørslett for his kind contribution of the ultraviolet image of Lathyrus pratensis, and Lars Chittka for helpful comments on the manuscript. Heather M. Whitney is in receipt of a Lloyd's of London Tercentenary foundation fellowship. Ruben Alvarez-Fernandez is in receipt of a fellowship from the Gobierno del Principado de Asturias (Spain), funded by Plan de Ciencia, Tecnologia e Innovacion (PCTI) of Asturias 2006–2009. This work was funded by Natural Environment Research Council grant NE/C000552/1, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council grant EP/D040884/1, the European RTN-6 Network Patterns, the Cambridge University Research Exchange, and German Academic Exchange Service DAAD.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Communicative & Integrative Biology E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cib/article/8084

References

- 1.von Frisch K. The Dance Language and Orientation of Bees. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Free JB. Effect of flower shapes and nectar guides on the behaviour of foraging honeybees. Behaviour. 1970;37:269–285. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Penny JHJ. Nectar guide color contrast. A possible relationship with pollination strategy. New Phytol. 1983;95:707–721. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heuschen B, Gumbert A, Lunau K. A generalised mimicry system involving angiosperm flower colour, pollen and bumblebees' innate colour preferences. Plant Syst Evol. 2005;252:121–137. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehrer M, Horridge GA, Zhang SW, Gadagkar R. Shape vision in bees: innate preferences for flower-like patterns. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B. 1995;347:123–137. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lunau K, Wacht S, Chittka L. Colour choices of naïve bumble bees and their implications for colour perception. J Comp Physiol [A] 1996;178:477–489. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waser NM, Price MV. The effect of nectar guides on pollinator preference: experimental studies with a montane herb. Oecologia. 1985;67:121–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00378462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waser NM, Price MV. Pollinator behaviour and natural selection for flower colour in Delphinium nelsonii. Nature. 1983;302:422–424. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biesmeijer JC, Giurfa M, Koedam D, Potts SG, Joel DM, Dafni A. Convergent evolution: floral guides, stingless bee nest entrances and insectivorous pitchers. Naturwissenschaften. 2005;92:444–450. doi: 10.1007/s00114-005-0017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dafni A. The functional ecology of floral guides in relation to insects behaviour and vision. In: Giurfa M, Wasser SP, editors. Evolutionary theory and processes: modern perspectives. Leiden: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 363–383. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gronquist M, Bezzerides A, Attygalle A, Meinwald J, Eisner M, Eisner T. Attractive and defensive functions of the ultraviolet pigments of a flower (Hypericum calycinum) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13745–13750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231471698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kay QON, Daoud HS, Stirton CH. Pigment distribution, light reflection and cell structure in petals. Bot J Linn Soc. 1981;83:57–84. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitney HM, Kolle M, Andrew P, Chittka L, Steiner U, Glover BJ. Floral iridescence, produced by diffractive optics, acts as a cue for animal pollinators. Science. 2009;323:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1166256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitney HM, Glover BJ. Morphology and development of floral features recognised by pollinators. Arthrop Plant Interact. 2007;1:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutowski RL, Macedonia JM, Morehouse N, Taylor-Taft L. Pterin pigments amplify iridescent ultraviolet signal in males of the orange sulphur butterfly, Colias eurytheme. Proc R Soc B. 2005;272:2329–2335. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shawkey MD, Hill GE. Carotenoids need structural colours to shine. Biol Lett. 2005;1:121–125. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutowski RL, Macedonia JM, Merry JW, Morehouse NI, Yturralde K, Taylor-Taft L, et al. Iridescent ultraviolet signal in the orange sulphur butterfly (Colias eurytheme): spatial, temporal and spectral properties. Biol J Linn Soc. 2007;90:349. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shawkey M, Morehouse NI, Vukusic P. A protean palette: Color materials and mixing in birds and butterflies. J R Soc Interface. 2009 doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0459.focus. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]