Abstract

Purpose

Given the increasing waiting time for liver transplantation, and the amount of possible stressors associated with it, assessment of psychological well-being and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in these patients is warranted in order to optimize pretransplant care.

Patients and methods

Patients with chronic liver disease (n = 32) awaiting transplantation completed a series of questionnaires measuring HRQoL, depression, anxiety, coping, and self-efficacy. Comparisons were made with other patients with liver disease with and without cirrhosis, and a healthy norm population. Relationships among these psychological variables were explored and subgroup analyses were performed to assess possible differences in coping strategies.

Results

Compared to other patients with liver disease without cirrhosis, liver transplant candidates had statistically significantly lower HRQoL scores on the subscales of physical functioning (P < 0.001) and general health (P < 0.001). Their HRQoL did not differ from patients with liver disease with cirrhosis. Overall, patients awaiting liver transplantation had significantly reduced HRQoL (P < 0.001) and increased depression scores (P < 0.001) compared to healthy controls. Levels of depression, anxiety, self-efficacy, and coping did not differ between liver transplant candidates and other patients with liver disease. Depression correlated significantly with HRQoL. Patients without depression made significantly more use of active coping strategies than patients with elevated depression levels.

Conclusions

Patients awaiting liver transplantation are not experiencing worse physical and psychological HRQoL than other liver patients with cirrhosis of the liver. Therefore, there is currently no indication to increase the level of psychosocial care for liver transplant candidates.

Keywords: Liver, Transplantation, Quality of life, HRQoL

Introduction

With the increase in patients with liver disease in need of a liver transplantation (748% between 1991 and 2003) outnumbering the increase in available donor organs (195% between 1991 and 2003), European liver patients’ time spent on the waiting list increases each year. There is evidence from research on heart or lung transplant patients that the time on the waiting list can be stressful, with patients expressing fear of death and worries about deteriorating health, among others [1–3]. Nevertheless, extensive data on the well being of patients listed for a liver transplantation are currently not available. Levels of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) are known to be lower before liver transplantation compared to after [4–11], but there is little knowledge of the influence of psychological variables on the experienced HRQoL of these patients. Levels of anxiety and depression have been reported to be elevated in different transplant patient populations, including patients with liver disease [11]. While these studies provide an insight into psychological variables that are important, it is not yet clear which variables contribute to possible decreased levels of HRQoL in patients awaiting liver transplantation. Moreover, limited data are available on actual levels of HRQoL for patients on the liver transplant list, and whether these are significantly lower than patients with liver disease who are not in need of a new liver.

Therefore, the first aim of this study was to assess the relative levels of HRQoL of patients awaiting liver transplantation and to compare them to other patients with chronic liver disease and a norm population of healthy persons. Given the stressful experience of awaiting transplantation, it was hypothesized that levels of HRQoL would be significantly lower in liver transplant candidates. The second aim of this study was to assess the relationships between HRQoL and several psychological variables such as anxiety, depression, and coping in liver transplant candidates. The levels of HRQoL and their psychological correlates will give an answer to the question, whether this patient group is in need of additional care in light of the stressful experience.

Materials and methods

Patient population

Questionnaire booklets were sent to all (n = 61) patients with chronic liver disease who are more than 16-year old, awaiting liver transplantation at the Erasmus MC (Rotterdam, the Netherlands) in May 2004. The indication for liver transplantation was end-stage liver failure due to cirrhosis with or without hepatocellular carcinoma. The waiting time for transplantation at that moment was dependent on time of the waiting list in combination with medical urgency criteria. Informed consent was given by returning the questionnaire booklet. The protocol was in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the modified 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Since the questionnaire booklets were only administered once and did not include invasive questions, ethical approval was not necessary under Dutch regulations.

Measurement instruments

Short form-36

The Short Form-36 (SF-36) is a widely used generic HRQoL questionnaire consisting of 36 questions that are combined into 8 scales on physical functioning, role limitations due to physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health. The scale scores vary between 0 and 100, with a higher score indicating a better generic HRQoL. An overall score can also be computed, with a range between 0.00 and 1.00, with higher scores indicating better HRQoL [12]. Reliability and validity of the SF-36 have long been established [13–16].

Beck’s Depression Inventory

The Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI-II-NL) is a 21-item self-report rating inventory measuring characteristic attitudes and symptoms of depression [17]. The total score ranges between 0 and 63, with scores below 14 considered normal, a score of 14–19 indicating mild to moderate depression, a score of 20–28 indicating moderate to severe depression, and scores higher than 28 indicating severe depression. Since physical symptoms associated with end-stage liver disease such as poor appetite and fatigue are also associated with depression, the scores of liver transplant candidates on the three separate factors of the BDI-II-NL (somatic, cognitive, and affective) were also computed. The cognitive- and affective-subscales do not include items pertaining to physical symptoms. Validity and reliability of the BDI-II-NL have been established [18–20].

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) is one of the most widely used instruments for measuring anxiety in adults. In this study, only trait anxiety was measured, which refers to a general tendency to respond with anxiety to perceived threats in the environment. The trait anxiety scale consists of 20 statements that assess how respondents feel “generally.” Scores can vary between 20 and 80, with higher scores indicating more anxiety. The STAI has been proven to be valid and reliable [21].

Self-efficacy scale

Self-efficacy reflects an optimistic self-belief that one can perform difficult or new tasks or that one can cope with adversity. The Self-Efficacy Scale (SES) consists of 10 items that are scored on a 4-point scale ranging from “not at all true” to “exactly true.” Scores vary between 10 and 40, with a higher score indicating better self-efficacy. Good reliability and construct validity of the SES were found in earlier studies [22–24].

Cognitive Operations Preference Enquiry-Easy

The Coping Operations Preference Enquiry-Easy (COPE-Easy) consists of 32 questions that incorporate 15 distinct coping strategies [25, 26]. Scores range between 2 and 8, with a higher score on a coping strategy indicating more use of that specific coping strategy. The 15 coping strategies can be grouped into three subscales: active problem focused coping, avoidant coping, and seeking social support [27]. Good reliability (Cronbach α = 0.67–0.91) for all coping strategies except for mental disengagement (Cronbach α = 0.57) has been established for the Dutch version of the COPE-Easy [27].

Statistical analysis

First, descriptive statistics were derived to explore the scores of liver transplant candidates on HRQoL, anxiety, depression, self-efficacy, and coping. Second, t-tests were performed to compare the scores of liver transplantation candidates to norm scores of a healthy population [13, 21, 23, 28] and the scores of other patients with and without cirrhosis of the liver which were randomly selected from the medical database of the Erasmus MC (Rotterdam, the Netherlands) (n = 164), controlled for age and gender (Gutteling et al., submitted). With the large amount of variables and comparison groups in this study, there was a reasonable chance of occurrence of false positives if the P value at which test statistics were considered statistically significant was not adjusted. Therefore, a new P value was calculated using the Bonferroni method: the amount of t-tests in this study was 41, the average Pearson correlation between the variables in the study was 0.43. A calculation [29] showed that test statistics with a P value of 0.006 and lower could be considered statistically significant, comparable with a P value of 0.05 for one t-test. Third, Pearson correlations between an overall score of HRQoL on the one hand and depression, anxiety, coping, and self-efficacy on the other were assessed to identify factors that showed a significant relationship with HRQoL. The correlation between HRQoL and length of waiting time was also computed. Additional analyses on subsamples were performed to assess possible differences in coping strategies and self-efficacy between patients with low and high depression and anxiety scores. Due to the small sample size, Mann–Whitney tests were performed.

Results

Patient characteristics

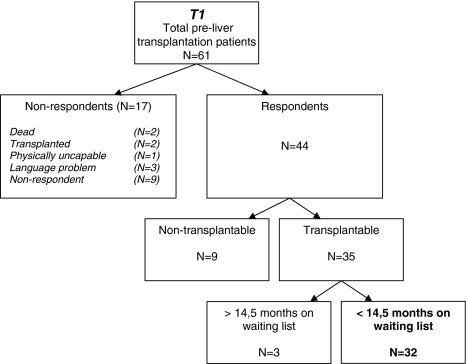

Out of the 61 patients who were sent a questionnaire booklet, nine did not want to participate for unknown reasons. Two patients were transplanted and two patients died before completing the questionnaires. One patient was physically ill to the extent that completion of the questionnaire booklet was impossible. Three patients did not speak Dutch well enough. In total, 44 patients participated (response rate = 72%). Out of these 44 patients, nine were considered nontransplantable owing to improvement of their liver disease after conservative medical management and were, therefore, excluded from the analyses. Three patients considerably spent more time on the waiting list than the other 32 (average of 727 days compared to 177 days), and were therefore not included in the analyses. The selection of patients is shown in Fig. 1. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the respondents, and Table 2 shows the mean scores of liver transplant candidates on HRQoL, depression, anxiety, self-efficacy, and coping.

Fig. 1.

Patients in the study

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of pre-liver transplantation patients, other liver patients without cirrhosis, other liver patients with cirrhosis, and a healthy norm population [32]

| Pre-liver transplantation (n = 32) |

Other liver patients | Healthy population (n = 1,742) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No cirrhosis (n = 101) |

Cirrhosis (n = 62) |

|||

| Gender (n, %) | ||||

| Male | 22 (69) | 51 (51) | 37 (60) | 976 (56) |

| Female | 10 (31) | 50 (49) | 25 (40) | 766 (44) |

| Age | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 52.5 (11.1) | 44.0 (12.6) | 49.4 (12.8) | 47.6 (18.0) |

| Range | (23–65) | (18–72) | (23–78) | (16–94) |

| Nationality (n, %) | ||||

| Dutch | 28 (87.5) | 91 (90.1) | 59 (95.2) | 1,655 (95) |

| Other | 4 (12.5) | 10 (9.9) | 3 (4.8) | 87 (5) |

| Time on waiting list in days (median, range) | 165 (1–436) | – | – | – |

| Disease etiology (n, %) | ||||

| Postalcoholic | 6 (19) | – | – | – |

| Cholestatic PBC PSC | 7 (22) | −38 (37.6) | 28 (45.2) | – |

| Viral | 10 (31) | 63 (62.4) | 34 (54.8) | – |

| Metabolic | 2 (6) | – | – | |

| Liver cancer | 1 (3) | – | – | – |

| Other | 6 (19) | – | – | – |

Table 2.

Mean scores and standard deviations on HRQoL, depression, anxiety, self-efficacy, and coping of pre-liver transplantation patients, other liver patients with and without cirrhosis, and a healthy norm population (Gutteling et al., submitted) and a healthy norm population [13, 21, 23, 28]

| Pre-liver transplantation (Mean, SD) |

Other liver patients (Mean, SD) |

Healthy norm (Mean, SD) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No cirrhosis | Cirrhosis | |||

| SF-36 overall score | 0.70 (0.09) | 0.73 (0.14) | 0.74 (0.14) | – |

| SF-36 physical functioning | 58.2 (23.1) | 76.4 (22.8)* | 73.5 (23.7) | 74.9 (23.4)* |

| SF-36 role physical functioning | 31.5 (37.6) | 55.0 (45.1) | 52.4 (44.3) | 76.4 (36.3)* |

| SF-36 bodily pain | 59.1 (26.8) | 68.8 (27.0) | 66.8 (26.8) | 74.9 (23.4)* |

| SF-36 general health | 30.6 (18.0) | 50.3 (23.4)* | 42.5 (22.6) | 70.7 (20.7)* |

| SF-36 vitality | 44.2 (16.8) | 50.6 (24.9) | 53.9 (24.4) | 68.6 (19.3)* |

| SF-36 social functioning | 66.0 (19.6) | 67.9 (29.4) | 74.4 (27.1) | 84.0 (22.4)* |

| SF-36 role emotional functioning | 67.8 (36.6) | 67.3 (42.4) | 61.2 (45.2) | 82.3 (32.9) |

| SF-36 mental health | 66.3 (18.4) | 66.9 (21.8) | 68.8 (23.6) | 76.8 (17.4)* |

| Depression overall (range 0–63) | 16.0 (7.9) | 12.6 (10.7) | 13.1 (12.0) | 6.2 (6.20)* |

| Anxiety (range 20–80) | 41.7 (10.9) | 41.1 (12.98) | 41.2 (13.37) | 38.4 (9.90) |

| Self-efficacy (range 0–40) | 29.9 (6.04) | 31.1 (6.09) | 30.3 (6.67) | 29.28 (5.09) |

| Active coping (range 1–4) | 2.63 (0.55) | 2.67 (0.64) | 2.52 (0.74) | – |

| Seeking support (1–4) | 2.40 (0.61) | 2.41 (0.76) | 2.24 (0.77) | – |

| Avoidant coping (1–4) | 1.89 (0.57) | 1.84 (0.66) | 1.89 (0.60) | – |

Note: The t-tests were performed with Bonferroni correction. Age and gender were controlled for

* P < 0.05

Statistical analysis

Comparison of liver transplant candidates with a norm population of healthy persons

Compared to a norm population of healthy persons, patients awaiting liver transplantation had significantly worse scores on all subscales of HRQoL, except the subscale “role emotional functioning,” reflecting the degree to which emotional problems interfere with work or other daily activities. Their mean depression score was also significantly worse. With regard to the distribution of scores, 13 patients had a mean score reflecting no depression, 10 patients had mild depression, 6 patients had moderately severe depression, and 3 patients had severe depression. The scores of liver transplant candidates on the subscales of the BDI-II-NL compared to the scores of a norm population of healthy persons can be seen in Table 3. About 52% of the liver transplant candidates had above-average scores on the cognitive and somatic subscales, and 60% of these patients had above-average scores on the “affective” subscale. There were no differences in the scores on mean anxiety and self-efficacy between patients awaiting liver transplantation and the norm population of healthy persons. However, eight patients (25%) had anxiety scores falling in the 10th percentile of a comparison group of healthy persons, reflecting clinical anxiety.

Table 3.

Scores of pre-liver transplantation patients on the subscales of the BDI-II-NL

| BDI-II-NL | n | Pre-liver transplantation patients Mean (SD) |

Healthy controls Mean |

25‰ | 50‰ | 75‰ | 90‰ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | 29 | 3.83 (3.60) | 1.4 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 |

| Affective | 30 | 2.3 (2.09) | 0.9 | 0 | 12 | 5 | 13 |

| Somatic | 29 | 9.76 (3.87) | 4.0 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 9 |

BDI-II-NL—Beck’s Depression Inventory

Comparison of liver transplant candidates with other patients with liver disease

Compared to other patients without liver cirrhosis, patients awaiting liver transplantation had significantly lower HRQoL scores on the subscales physical functioning (P < 0.001) and general health (P < 0.001). The scores on the subscales of the SF-36 reflecting bodily pain, role physical functioning, and the psychosocial domains of HRQoL did not differ for liver transplant candidates without cirrhosis and other patients with chronic liver disease. Compared to patients with liver cirrhosis, liver transplant candidates did not have statistically significantly lower HRQoL scores, but the subscale physical functioning did show a trend (P < 0.007; remember that due to the Bonferroni correction, a P < 0.006 was required). There were no statistically significant differences with regard to self-efficacy, anxiety, depression, and coping between liver transplant candidates and hepatology patients with and without cirrhosis of the liver.

Correlations between HRQoL, time on waiting list, and psychological variables

The results of the correlation analysis are shown in Table 4. Of all the psychological variables in the analysis, HRQoL of liver transplant candidates was statistically significantly correlated with only depression (r = 0.43, P < 0.05). Length of waiting time was not significantly correlated with HRQoL or with any of the psychological variables.

Table 4.

Pearson correlations between the overall score of HRQoL, time on waiting list, and psychological variables in liver patients awaiting transplantation

| HRQoL (overall) | Time on waiting list | |

|---|---|---|

| Time on waiting list | −0.34 | 1.00 |

| Depression | −0.43* | −0.20 |

| Anxiety | −0.32 | −0.14 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.16 | 0.18 |

| Active coping | −0.02 | 0.04 |

| Seeking social support | −0.16 | 0.18 |

| Avoidant coping | −0.11 | 0.14 |

HRQoL—Health-related quality of life

* P < 0.05

Subgroup analyses

Liver transplant candidates without depression (n = 13) made significantly more use of active coping (Z = −3.14, P < 0.01) than liver transplant candidates with higher depression scores (n = 19). A trend was seen for avoidant coping, with nondepressed patients making less use of maladaptive coping than patients with higher depression scores (Z = −1.95, P = 0.05). Patients without depression had significantly higher scores on self-efficacy (Z = −3.12, P < 0.05) than patients with higher depression scores. With regard to anxiety, it was shown that patients with low anxiety scores (n = 24) had significantly higher self-efficacy scores than patients with high anxiety scores (n = 8) (Z = −2.27, P < 0.05). No differences were found between patients with low- and higher-depression scores on the coping strategy of social support seeking. This was also true for patients with low- and higher-anxiety scores. Furthermore, these patients did not differ in their use of active and avoidant coping strategies.

Discussion

In comparison with other patients with liver disease without cirrhosis of the liver, physical HRQoL was impaired, while the level of physical HRQoL of patient with cirrhosis of the liver and liver transplant candidates was comparable. Overall, liver transplant candidates did not have worse mental HRQoL and were not more depressed than patients with less advanced liver disease. They were also not more anxious, and their coping and self-efficacy styles did not differ. However, nine (15%) of the liver transplant candidates had moderate to severe depression, and 25% had anxiety scores reflecting clinical anxiety. HRQoL correlated significantly with depression, but not with the other psychological variables.

An interesting finding in the current study, contrary to the hypothesis, was the lack of differences between patients with liver disease and transplant candidates on mental HRQoL and several of the psychological variables such as anxiety and coping. While the experience of waiting for a new liver is certainly likely to be stressful, there was no evidence to support that it is significantly more stressful than being diagnosed with chronic liver disease. In addition, it is certainly possible that while the experience is more stressful, the provision of hope through the possibility of liver transplantation counters adverse outcomes in terms of well-being [30]. Depression levels were related to HRQoL, which is in line with previous research in other patient populations [31–33]. Further, subgroup analyses indicated that levels of self-efficacy and active coping were lower for liver transplant candidates with elevated depression scores. This information may prove useful when developing interventions to improve HRQoL.

Several limitations of this study should be mentioned. First of all, the sample size of this study was small. However, it must be noted that with a response rate of 72% of all patients listed for transplantation at the Erasmus Medical Center at a particular point in time, the amount of patients in this study can be considered relatively large. While one should be cautious when drawing any firm conclusions based on the results of this study, it must be noted that the small sample size was taken into consideration when performing the statistical analyses. Furthermore, the results were in line with previous studies. The higher age, and unequal distribution, of men and women in the sample of transplantation candidates compared to the comparison groups were controlled for in the statistical analysis. A final limitation of this study is the fact that the patients in our sample had been awaiting transplantation for a relatively short period of time (median 165 days, with patients commonly waiting approximately 2 years to be transplanted), which may explain the lack of correlation between HRQoL and time on waiting list. Clearly, further research is needed in order to draw conclusions on the effect of waiting time on HRQoL.

Conclusions

Contrary to what was hypothesized, patients awaiting liver transplantation are not experiencing worse HRQoL than patients with an advanced liver disease. Their HRQoL and scores on depression and anxiety did not differ from those of other patients with liver disease with cirrhosis. The elevated depression and anxiety scores that were found seem, therefore, to be inherent in the seriousness of chronic liver disease per se rather than the fact that these patients are awaiting transplantation. The results of the present study imply that there is no indication to routinely provide liver transplant candidates with additional psychosocial care. Instead, physicians should be sensitive to symptoms of anxiety and depression that are to be expected in any patient population with serious chronic disease. Given the relationship of depression and the psychological variables of coping and self-efficacy, it is advisable to refer patients awaiting liver transplantation with impaired HRQoL and depression to psychological counseling that focuses on teaching these psychological constructs.

References

- 1.Cupples SA, Nolan MT, Augustine SM, Kynoch D. Perceived stressors and coping strategies among heart transplant candidates. J Transpl Coord 1998;8(3):179–87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Jalowiec A, Grady KL, White-Williams C. Stressors in patients awaiting a heart transplant. Behav Med 1994;19(4):145–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Porter RR, Krout L, Parks V, Aaronson NK. Perceived stress and coping strategies among candidates for heart transplantation during the organ waiting period. J Heart Lung Transplant 1994;13(1 Pt 1):102–7. [PubMed]

- 4.Karam V, Castaing D, Danet C, Delvart V, Gasquet I, Adam R, et al. Longitudinal prospective evaluation of quality of life in adult patients before and one year after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2003;9(7):703–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.De Bona M, Ponton P, Ermani M, Iemmolo RM, Feltrin A, Boccagni P, et al. The impact of liver disease and medical complications on quality of life and psychological distress before and after liver transplantation. J Hepatol 2000;33(4):609–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Lahteenmaki A, Hockerstedt K, Kajaste S, Huttunen M. Quality of life before and after liver transplantation: experiences with 7 patients with primary biliary cirrhosis in a 2-year follow-up. Transpl Int 1992;5(Suppl 1):S705–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ratcliffe J, Longworth L, Young T, Bryan S, Burroughs A, Buxton M. Assessing health-related quality of life pre- and post-liver transplantation: a prospective multicenter study. Liver Transpl 2002;8(3):263–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Shih FJ, Hu RH, Ho MC, Lin HY, Lin MH, Lee PH. Changes in health-related quality of life and working competence before and after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 2000;32(7):2144–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Burra P, De Bona M, Canova D, Painter L. Longitudinal prospective study on quality of life and psychological distress before and one year after liver transplantation. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2005;68(1):19–25. [PubMed]

- 10.Beilby S, Moss-Morris R, Painter L. Quality of life before and after heart, lung and liver transplantation. N Z Med J 2003;116(1171):U381. [PubMed]

- 11.Streisand RM, Rodrigue JR, Sears SF Jr, Perri MG, Davis GL, Banko CG. A psychometric normative database for pre-liver transplantation evaluations. The Florida cohort 1991–1996. Psychosomatics 1999;40(6):479–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ 2002;21(2):271–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, Essink-Bot ML, Fekkes M, Sanderman R, et al. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51(11):1055–68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), II: psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care 1993;31(3):247–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Razavi D, Gandek B. Testing Dutch and French translations of the SF-36 Health Survey among Belgian angina patients. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51(11):975–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30(6):473–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961;4:561–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK, van der Does AJW. Handleiding bij de BDI-II-NL. Enschede, the Netherlands: Ipskamp; 1996.

- 19.Beck AT, Steer R, Garbin M. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 1988;8(1):77–100. [DOI]

- 20.Richter P, Werner J, Heerlein A, Kraus A, Sauer H. On the validity of the Beck Depression Inventory. A review. Psychopathology 1998;31(3):160–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.van der Ploeg HM. Handleiding bij de Zelf Beoordelings Vragenlijst. Lisse, the Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger BV; 2000.

- 22.Leganger A, Kraft P, Roysamb E. Perceived self-efficacy in health behavior research: conceptualisation, measurement and correlates. Psychol Health 2000;15:51–69.

- 23.Scholz U, Gutiérrez-Doña B, Sud S, Schwarzer R. Is perceived self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. Eur J Psychol Assess 2002;18(3):242–51. [DOI]

- 24.Schwarzer R, Jeruzalem M. Generalized self-efficacy scale. In: Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M, editors. Measures in health psychology: a user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs. Windsor, England: NFER-NELSON; 1995. p. 35–7.

- 25.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the Brief COPE. Int J Behav Med 1997;4(1):92–100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989;56(2):267–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Kleijn WC, van Heck GL, van Waning A. Ervaringen met een Nederlandse bewerking van de COPE copingvragenlijst. De COPE-Easy. Experiences with a Dutch adaptation of the COPE coping questionnaire: the COPE-Easy. Gedrag Gezond Tijdschr Psychol Gezond 2000;28(4):213–26.

- 28.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown BW Jr, van der Does AJW. Beck Depression Inventory II, NL Handleiding. Lisse: Harcourt Test Publishers; 1996.

- 29.Sankoh AJ, Huque MF, Dubey SD. Some comments on frequently used multiple endpoint adjustment methods in clinical trials. Stat Med 1997;16(22):2529–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Goetzmann L, Wagner-Huber R, Klaghofer R, Muellhaupt B, Clavien PA, Buddeberg C, et al. Waiting for a liver transplant: psychosocial well-being, spirituality, and need for counselling. Transplant Proc 2006;38(9):2931–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Shen BJ, Myers HF, McCreary CP. Psychosocial predictors of cardiac rehabilitation quality-of-life outcomes. J Psychosom Res 2006;60(1):3–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Hofer S, Benzer W, Alber H, Ruttmann E, Kopp M, Schussler G, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life in coronary artery disease patients: a prospective study generating a structural equation model. Psychosomatics 2005;46(3):212–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Bechdolf A, Klosterkotter J, Hambrecht M, Uda H. Determinants of subjective quality of life in post acute patients with schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003;253(5):228–35. [DOI] [PubMed]