Abstract

Formation of the nuclear envelope (NE) around segregated chromosomes occurs by the reshaping of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), a reservoir for disassembled nuclear membrane components during mitosis. In this study, we show that inner nuclear membrane proteins such as lamin B receptor (LBR), MAN1, Lap2β, and the trans-membrane nucleoporins Ndc1 and POM121 drive the spreading of ER membranes into the emerging NE via their capacity to bind chromatin in a collaborative manner. Despite their redundant functions, decreasing the levels of any of these trans-membrane proteins by RNAi-mediated knockdown delayed NE formation, whereas increasing the levels of any of them had the opposite effect. Furthermore, acceleration of NE formation interferes with chromosome separation during mitosis, indicating that the time frame over which chromatin becomes membrane enclosed is physiologically relevant and regulated. These data suggest that functionally distinct classes of chromatin-interacting membrane proteins, which are present at nonsaturating levels, collaborate to rapidly reestablish the nuclear compartment at the end of mitosis.

Introduction

The nuclear envelope (NE) is composed of two lipid bilayers, the inner nuclear membrane (INM) and the outer nuclear membrane, which are fused at sites of nuclear pore complex (NPC) insertion (Hetzer et al., 2005). Although the NE is continuous with the ER (Voeltz et al., 2002), the INM contains a unique set of integral membrane proteins that provide functional interactions with chromatin and the nuclear lamina (D'Angelo and Hetzer, 2006). In metazoan cells, the nucleus disassembles at the onset of mitosis, facilitating spindle access to chromosomes (Burke and Ellenberg, 2002). During NE breakdown, transmembrane proteins of the NE are redistributed into the ER, which remains intact during mitosis (Ellenberg et al., 1997; D'Angelo and Hetzer, 2006). Consequently, the sheetlike NE must reemerge from ER membranes during nuclear assembly (Ellenberg et al., 1997; Anderson and Hetzer, 2007, 2008a). We have recently shown that this massive membrane-restructuring event is initiated by the recruitment of tubule ends to chromatin (Anderson and Hetzer, 2007). This initial step is followed by the coating of the chromosome mass by ER membranes and their subsequent reorganization into the NE (Anderson and Hetzer, 2008a). Although these results suggest that chromatin acts as a structural mediator of NE formation, the principle mechanism that generates the nuclear membrane from the ER remains unclear.

There is no agreement on whether the mitotic ER is entirely tubular (Puhka et al., 2007) or largely composed of sheets (Lu et al., 2009). We recently demonstrated that the removal of reticulons and DP1, which are membrane-bending proteins that mediate tubule formation (Voeltz et al., 2006), from the reforming NE is rate limiting for nuclear assembly. This suggests that the transition of the ER into the flat NE leaflets requires a reduction in localized membrane curvature (Voeltz et al., 2002; Shibata et al., 2006). Thus, a mechanism must exist that counteracts membrane bending (Voeltz et al., 2006) and drives the local membrane spreading and redistribution around chromatin. One class of proteins that could fulfill such a function is the transmembrane proteins of the INM that have been shown to bind chromatin early during NE formation and have also been implicated in the targeting of membranes to chromosomes (Pyrpasopoulou et al., 1996; Ellenberg and Lippincott-Schwartz, 1999; Haraguchi et al., 2000). Although it has been postulated that such proteins are important for NE formation, the relative contributions of these proteins to the process in vivo are not well understood.

Results and discussion

Measuring NE formation in vivo

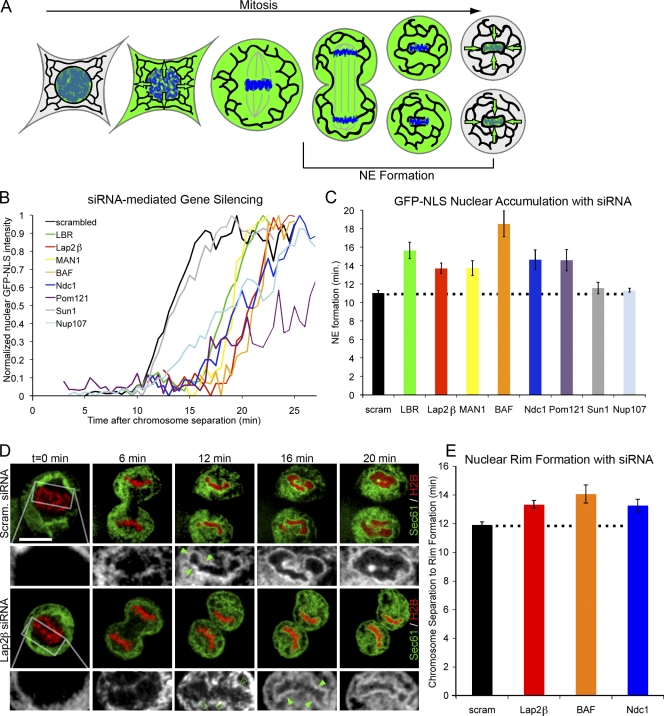

To analyze NE assembly in living cells, we used a previously established quantitative assay that allows us to determine the potential role of membrane proteins in NE formation by time-lapse microscopy (Fig. 1 A; Haraguchi et al., 2000; Anderson and Hetzer, 2008a; Dultz et al., 2008). In brief, we monitor the time between the initiation of chromosome separation (t = 0), visualized by a histone H2B–tdTomato reporter, and the onset of nuclear accumulation of GFP-NLS, which marks the completion of NE formation (Anderson and Hetzer, 2008b; Antonin et al., 2008; Dultz et al., 2008). Using this assay, we determined that in U2OS and HeLa cells, NE formation was completed within ∼10 min (Fig. 1, B and C; Anderson and Hetzer, 2008b; Dultz et al., 2008).

Figure 1.

Chromatin-binding NE proteins collaborate during NE formation. (A) Diagram shows the dynamic localization of nuclear-targeted GFP (green) during open mitosis. Reaccumulation of GFP-NLS into daughter nuclei serves as an indicator for completed NE formation. (B) Cells were transfected with H2B-tdTomato and GFP-NLS and imaged through mitosis. Representative traces of chromatin-localized GFP-NLS in which t = 0 is set at the onset of chromosome separation show the time required for NE formation in U2OS cells with reduction of protein levels by siRNA knockdown. (C) Average time from chromosome separation to GFP-NLS nuclear accumulation was plotted. n > 20 for each condition (Table S1) with P < 0.01 when LBR, Lap2β, MAN1, BAF, Ndc1, or Pom121 siRNA was compared with scrambled (scram) RNA control, and P = 0.23 and 0.20 for Sun1 and Nup107, respectively (by t test). (D) U2OS cells were transfected with H2B-tdTomato (red) and Sec61-GFP (green, black, and white insets) and imaged from mitosis. Nuclear rim formation was compared in cells transfected with scrambled RNA or siRNA against Lap2β (closed arrowheads). After 12 min, no nuclear rim was detected with the knockdown of Lap2β (open arrowheads) compared with rim signal present in scrambled siRNA controls. Outlined areas represent the regions that are magnified below. Bar, 20 µm. (E) Average time from chromosome separation to complete nuclear rim formation was plotted. P < 0.01 when Lap2β, BAF, or Ndc1 knockdown was compared with scrambled RNA. Dotted lines indicate control cell timing. Error bars indicate SEM.

Reduced levels of INM proteins limit the rate of NE formation

To test the potential involvement of NE proteins in promoting membrane targeting to and reshaping on chromatin, we reduced the levels of the INM proteins lamin B receptor (LBR), Lap2β, and MAN1, which were chosen because of their known ability to bind chromatin (Gant et al., 1999; Holmer and Worman, 2001; Foisner, 2003; Liu et al., 2003), in U2OS cells using RNAi-mediated gene silencing (Fig. S1 A). We found that reductions of each of these proteins significantly delayed NE formation when compared with control cells transfected with scrambled RNA oligos (Fig. 1, B and C). Knockdown of the INM protein Sun1, which does not bind chromatin (Crisp et al., 2006), or the nucleoporin Nup107, whose reduction has been shown to block pore assembly (Walther et al., 2003), had no significant effect on the onset of GFP-NLS accumulation (Fig. 1, B and C). This suggests that only a subset of NE proteins is involved in NE formation. The finding that depletion of LBR, Lap2β, or MAN1 resulted in a delay, but not a complete block of NE formation, indicated that each of these proteins functionally contributes to the formation of a closed NE in a manner consistent with built-in redundancy.

Functionally distinct chromatin-interacting proteins mediate NE formation

Several INM proteins have been shown to bind DNA through different chromatin-associated proteins. For example, LBR interacts with heterochromatin protein 1 (Ye and Worman, 1996), whereas Lap2β and MAN1 bind to the barrier of autointegration factor (BAF) via their Lap2/emerin/Man1 (LEM) domains (Furukawa et al., 1998). Therefore, it was important to test whether these INM proteins interact with chromatin at nonoverlapping sites during nuclear assembly. If this were the case, the knockdown of BAF, which has been shown to be involved in NE formation (Segura-Totten et al., 2002; Gorjanacz et al., 2007; Haraguchi et al., 2008), should also delay but not block nuclear assembly. Indeed, we found that with efficient BAF depletion, NE formation occurred, but at significantly reduced rates (Fig. 1, B and C). NE formation delay with reduced BAF levels was more extreme than that seen with either Lap2β or Man1, which is consistent with the idea that BAF may mediate interactions between several proteins.

A recent study showed that several NE proteins, including the transmembrane nucleoporins Ndc1 and POM121, can bind DNA in vitro (Ulbert et al., 2006). This raised the interesting possibility that functionally distinct classes of proteins, such as NPC components, might participate in NE formation. To test this, we knocked down Pom121 and Ndc1 (Mansfeld et al., 2006) and found that NE formation was significantly delayed (Fig. 1, B and C). Importantly, although reduction of Ndc1 slightly reduced the rate of transport, which is consistent with its role in NPC assembly (Stavru et al., 2006), it did not inhibit nuclear GFP-NLS accumulation (Fig. 1 B), suggesting that the observed delay in NE formation was not the result of a defect in NPC assembly. This is consistent with the finding that when the nuclear pore number (and thus transport rate) is reduced by the reduction of Nup107, the onset of import and NE formation times were similar to control cells (Fig. 1, B and C). Thus, the NE formation time reported by our assay is independent of transport rate. Collectively, these findings suggest that different classes of integral nuclear membrane proteins, which have the capacity to bind chromatin as a common feature, collaborate during mitosis to promote NE formation.

Reduction of BAF, Lap2β, or Ndc1 delays final stages of NE formation

NE formation proceeds through two distinct steps: the targeting of membranes to chromatin and reshaping of ER membranes into an NE sheet (Anderson and Hetzer, 2007). To test whether INM proteins participate in NE sheet formation, we used a recently developed method (Anderson and Hetzer, 2008a) and measured the fluorescence intensity of Sec61-GFP, an NE/ER marker (Anderson and Hetzer, 2007), at the forming NE (Fig. S1, C and D). Reduction of Lap2β or BAF did not significantly delay the increase in Sec61-GFP intensity during early stages of NE formation, suggesting that the initial targeting of ER membranes was not affected. Surprisingly, knockdown of either protein was able to reduce Sec61-GFP intensity during the last few minutes of NE formation, suggesting that the final spreading of membranes around chromatin and subsequent closure are affected by the reduction of each of these proteins (Fig. S1 D). Consistent with this, high resolution imaging revealed that the reduction of either Lap2β, BAF, or Ndc1 protein levels delayed the appearance of a nuclear rim, which is an unequivocal indicator of the formation of a flat NE (Fig. 1, D and E; Anderson and Hetzer, 2008a). Together, these data confirm the findings from the import assay and suggest that Lap2β, BAF, and Ndc1 reductions decrease the efficiency of NE formation during the final stages of assembly and closure.

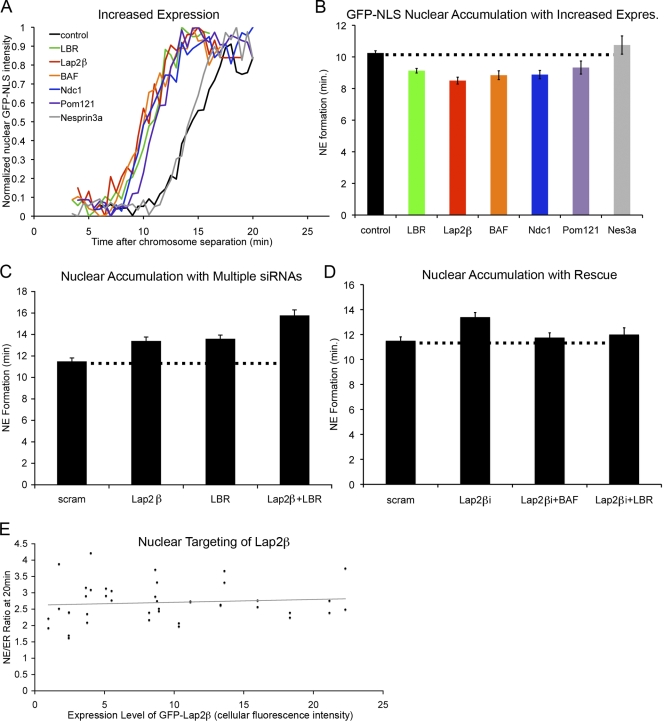

INM proteins are positive regulators of NE formation

Because multiple NE proteins collaborate in nuclear membrane formation, yet knockdowns of single components result in a significant delay in nuclear assembly, it is suggested that the concentrations of chromatin-binding NE proteins are nonsaturating at endogenous levels and that an excess of binding sites exist on chromatin. One prediction from this hypothesis is that the rate of NE formation is a function of the levels of chromatin-binding membrane proteins, and therefore, increasing their concentrations should accelerate nuclear assembly. To test this, we expressed V5-tagged versions of Lap2β, LBR, Pom121, and Ndc1. All constructs were found to properly localize to the nuclear rim (Fig. S2 A), and Western blotting showed that these proteins were expressed at up to ∼8 times the endogenous levels (unpublished data). Strikingly, cells expressing additional Lap2β, LBR, BAF, Pom121, or Ndc1 accelerated nuclear formation (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast, the overexpression of the outer nuclear membrane protein nesprin-3a (Ketema et al., 2007) did not increase the rate of nuclear assembly (Fig. 2, A and B). The latter suggests that the observed acceleration in NE formation is a phenomenon unique to proteins containing chromatin interaction domains. Interestingly, we did not observe additional acceleration of NE formation when Lap2β and LBR were coexpressed, suggesting that multiple rate-determining steps may exist and that other events, such as the previously described displacement of reticulons (Anderson and Hetzer, 2008a), likely contributes to the maximum rate of nuclear assembly.

Figure 2.

Chromatin-interacting NE proteins promote nuclear assembly. (A) Cells were transfected as in Fig. 1 B and imaged through mitosis. Representative traces of chromatin-localized GFP-NLS in which t = 0 is set at the onset of chromosome separation show the time required for NE formation in U2OS cells in which protein levels were increased by transfection with epitope-tagged constructs. (B) Average time from chromosome separation to GFP-NLS nuclear accumulation was plotted. P < 0.001 when Lap2β, LBR, BAF, Ndc1, or Pom121 increased expression (expres) was compared with control cells, and P = 0.20 for nesprin-3a (Nes3a; Table S2). (C) NE formation time was measured after partial knockdown of Lap2β, LBR, or both with a single round of siRNA transfection when Lap2β or LBR were compared with scrambled (scram) RNA oligos or when Lap2β + LBR was compared with Lap2β or LBR alone (P < 0.001; Table S3). (D) NE formation time was measured after partial knockdown of Lap2β combined with overexpression of either BAF or LBR and compared with the partial knockdown alone (P > 0.20 for each). (E) U2OS cells were transfected with GFP-Lap2β and H2B-tdTomato and imaged through mitosis. Average GFP fluorescence intensity was measured over entire cell and plotted against the ratio of GFP-Lap2β at the NE to peripheral GFP-Lap2β (NE/ER ratio). n > 20 for each condition (Table S3). Dotted lines indicate control cell timing. Error bars indicate SEM.

To further test the possibility that mediators of NE formation work collaboratively, we decided to perform combinations of NE protein knockdowns. We reduced the levels of LAP2β and LBR either alone or in combination and found that NE formation was delayed twice as much in cells with double knockdown compared with cells in which the levels of only one of the proteins had been reduced (Fig. 2 C). This suggests that these proteins have nonoverlapping functions and that recruitment of each protein to chromatin contributes to the rate of NE formation.

One prediction from this is that the knockdown of one INM protein should be rescued by the overexpression of a different chromatin-binding INM component. In support of this idea, we found that the delay in NE formation associated with Lap2β knockdown is attenuated in cells in which either BAF or LBR levels were transiently increased (Fig. 2 D and Fig. S2 C). Therefore, the rate of NE formation is at least in part determined by the relative amounts of INM proteins that can bind chromatin or DNA, and these proteins act in a highly redundant manner during assembly.

Nuclear targeting of Lap2β is independent of expression level

To directly test whether the targeting of NE proteins to chromatin is not saturating at endogenous levels, U2OS cells were transfected with GFP-Lap2β, and the efficiency of NE targeting during nuclear assembly was measured 20 min after chromosome separation (Fig. 2 D). Consistent with the idea that there is an excess of binding sites for INM proteins on chromatin, the NE/ER ratio of GFP-Lap2β was constant over a wide range of expression levels. Therefore, we conclude that proteins involved in the targeting of membranes to chromatin promote NE formation and that at endogenous levels they limit the rate of assembly. The finding that each of these proteins limits the rate of nuclear assembly along with their nonsaturating concentrations implies an abundance of chromatin-docking sites. This notion is consistent with recent findings that the bulk of NE proteins are completely cleared from the surrounding ER during the early stages of NE formation (Anderson and Hetzer, 2007).

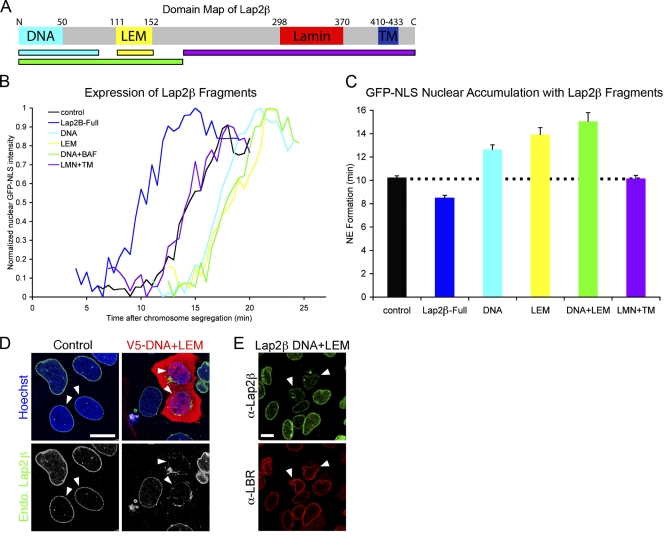

Tethering of membranes to chromatin is required for NE formation acceleration

To further characterize the molecular mechanisms by which INM proteins bind chromatin, we generated truncations of Lap2β, including the DNA- and BAF-binding (LEM) domains as well as the lamin-interacting domain and transmembrane region (LMN + TM; Fig. 3 A). When a Lap2β fragment (LMN + TM) lacking both the DNA-binding and LEM domains was expressed, no significant change in the rate of NE formation was detected (Fig. 3, B and C) despite its localization to the NE (Fig. S2 B). This suggests that tethering of the transmembrane domain to the chromatin-interacting domains is required for promoting nuclear membrane formation. In contrast, when we overexpressed the DNA and LEM domains of Lap2β (Fig. 3 A), NE formation was significantly delayed, suggesting that these soluble fragments act as competitive inhibitors for the targeting of endogenous Lap2β or other LEM domain proteins to chromatin (Fig. 3, B and C). To directly test this, the DNA + LEM fragment was transfected into U2OS cells and endogenous Lap2β localization visualized by immunofluoresence (Fig. 3 D). In cells expressing the chromatin interaction fragment, endogenous Lap2β was found to be greatly reduced at the NE in early G1 cells and was mainly found in perinuclear aggregates, suggesting a competitive inhibition by this fragment. Interestingly, in cells where endogenous Lap2β was displaced, as indicated by characteristic irregular NE staining, LBR targeting was unaffected (Fig. 3 E). This suggests that Lap2β and LBR promote NE assembly by tethering of the transmembrane domain to distinct chromatin sites, which is consistent with previous findings of nonoverlapping binding of LBR and Lap2β on chromatin (Haraguchi et al., 2008).

Figure 3.

Membrane–chromatin tethering function of Lap2β in NE formation. (A) Map of Lap2β shows distinct functional domains that interact with DNA, BAF (LEM), lamins, and lipid bilayer (TM). (B) Representative traces of chromatin-localized GFP-NLS in which t = 0 is set at the onset of chromosome separation show the time required for NE formation in U2OS cells where fragments of Lap2β, DNA, LEM, DNA + LEM, or LMN + lipid bilayer have been overexpressed. (C) NE formation time was measured with the expression of Lap2β fragments. n > 40 for each fragment. P < 0.001 for the expression of DNA, LEM, and DNA + LEM fragments when compared with control cells; P = 0.4 for LMN + TM. Dotted line indicates control cell timing. Error bars indicate SEM. (D) U2OS cells were transfected with the V5-DNA + LEM fragment of Lap2β and stained with antibodies against V5 (red) and endogenous (endo) Lap2β (green). Arrowheads indicate early G1 cells as indicated by nuclear size and paired orientation. (E) U2OS cells were transfected with the DNA + LEM fragment of Lap2β and stained with antibodies against endogenous Lap2β and LBR. Arrowheads indicate cells where endogenous Lap2β, but not LBR, is displaced by the chromatin-binding domain of Lap2β. Bars, 20 µm.

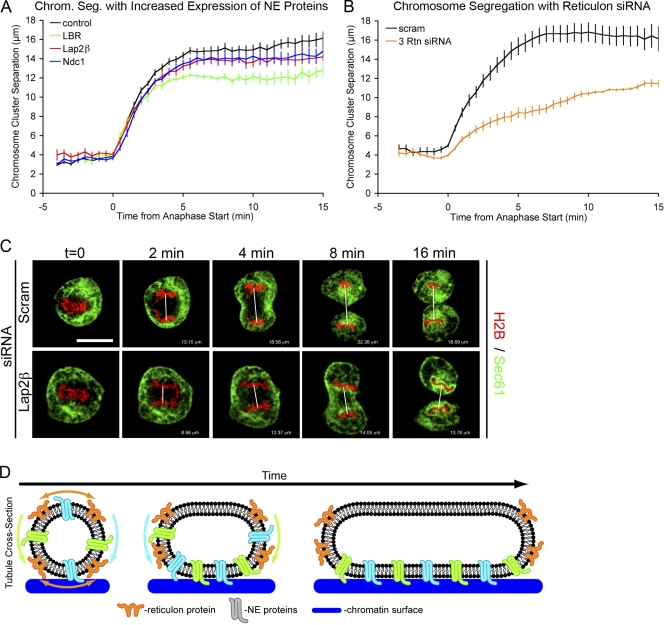

Accelerating NE formation decreases chromosome separation during mitosis

The existence of multiple proteins that modulate the rate of NE formation as well as the finding that the process can be accelerated suggests that nuclear assembly is a highly regulated process. This raises the interesting question of whether imbalances in the levels of NE-forming proteins might interfere with normal cell cycle progression. To test this possibility, nuclear assembly was accelerated in U2OS cells by overexpressing LBR, Lap2β, or Ndc1, and the distance between segregating chromosomes was measured during anaphase as a function of time. Increasing the levels of each of these proteins caused a modest but significant decrease in the separation of chromosome clusters (Fig. 4, A and C). Notably, we did not observe anaphase bridges, and therefore, it is unlikely that this phenotype stems from defects in global chromatin organization.

Figure 4.

Acceleration of nuclear membrane formation causes chromosome segregation defect. (A) Mitosis was analyzed by transfecting U2OS cells with Sec61-GFP and H2B-tdTomato and comparing control cells with cells in which NE formation was accelerated by overexpression of LBR, Lap2β, or Ndc1. Chromosome cluster separation (chrom seg) is plotted over time with P < 0.001 for Boltzmann Sigmoidal curve fitting to control cells. (B) Chromosome cluster separation plotted over time for extreme NE formation acceleration caused by the siRNA knockdown of reticulons 1, 3, and 4. (C) Representative images of U2OS cells with Sec61-GFP (green) and H2B-tdTomato (red) compares control cells with cells in which NE formation was accelerated by overexpression of Lap2β, and the distance between chromosome clusters was measured. t = 0 is set at anaphase onset. White lines indicate distances measured in Photoshop extended. Bar, 20 µm. (D) Cross-sectional schematic of a membrane tubule expanding onto chromatin (blue). Reticulons (orange) are displaced from the flat membrane where INM proteins (green) are targeted to chromatin and drive membrane expansion around chromatin. Error bars indicate SEM.

We have previously shown that siRNA knockdown of reticulons 1, 3, and 4 in combination increases the rate on NE formation (Anderson and Hetzer, 2008a). These ER proteins are excluded from chromosomes at all times and are therefore unlikely to affect chromatin organization. Additionally, the reduction of reticulons accelerated NE formation ∼1.5 min faster than that demonstrated with the increased expression of NE proteins (Anderson and Hetzer, 2008a). In cells with reduced reticulons, a striking impairment in the separation of chromosomes was observed (Fig. 4 B), suggesting that decreased chromosome separation was indeed caused by the premature spreading of membranes around the chromosome clusters, possibly inhibiting the ability for the mitotic spindle to pull the chromosome masses apart. This suggests that regulating the rate of NE formation may be necessary for proper cell cycle progression and thus is coordinated with other mitotic events in anaphase/telophase.

In summary, our data suggest that endogenous concentrations of NE-promoting transmembrane proteins limit the rate of nuclear assembly as indicated by their overexpression accelerating the process (Fig. 2, A and B). NE formation is also affected by endogenous levels of the ER-shaping reticulon proteins (Anderson and Hetzer, 2008a) that slow NE formation. These findings suggest a tug of war between reticulons and their membrane-curving activity and NE proteins, which promote membrane attachment and spreading around chromatin. We propose that the massive membrane-restructuring event that results in the formation of the sheetlike NE involves functionally diverse groups of NE proteins that collaborate during mitosis to tether membranes to the chromatin surface and thereby drive NE formation.

Our findings suggest that NE formation relies on the intrinsic propensity of the ER to efficiently transition between tubules and sheets (Voeltz et al., 2002) to reorganize membranes at the chromatin surface into the forming NE at the conclusion of each mitotic cycle. To shift this equilibrium toward sheet formation, the chromatin-binding capacity of NE proteins is used to coat the entire chromosome mass with a closed NE. This massive membrane-restructuring event is accomplished by the collaboration of functionally distinct classes of NE proteins and their ability to bind chromatin. Our findings are consistent with the idea that INM proteins serve to anchor ER membranes at the chromatin surface and promote the morphological changes associated with the spreading of the membranes onto and around the chromatin surface (Fig. 4 D; Anderson and Hetzer, 2007). It remains to be seen whether chromatin-mediated tubule to sheet transitions or the recruitment of ER sheets is the main mechanism of NE formation, although both ideas are not mutually exclusive.

In principle, the number of NE-forming transmembrane proteins might be substantial, as ∼40 NE proteins exhibit DNA-binding potential (Ulbert et al., 2006).Notably, although proteins like Lap2β and LBR appear to interact with chromatin in a nonoverlapping fashion, reductions in either one or both of these proteins is unable to completely block NE formation and is indicative of a redundant system. The large number of NE proteins may provide a fail-safe mechanism, increasing the reliability of NE formation by multiplying critical components. In such a system, if a single NE-promoting protein fails to target, NE formation can still be accomplished, although possibly at a slower rate. This is consistent with the finding that despite the observed collaboration, many of these proteins contribute to the overall rate of NE formation. In light of the finding that acceleration of NE formation interferes with normal chromosome separation during mitosis, the proposed regulatory role of NE membrane proteins may be relevant to human disease. It will be interesting to test whether such a defect occurs in cancer cells in which the up-regulation of Lap2β has recently been described (Somech et al., 2007).

Materials and methods

Molecular constructs and antibodies

Human Lap2β, LBR, BAF, Ndc1, Pom121, and nesprin-3a were amplified by PCR from IMAGE clones (Open Biosystems) and inserted into the V5-containing pcDNA6.2/Lumio (V5 of either N or C terminus) vectors using Gateway cloning (Invitrogen). Fragments of human Lap2β were amplified by PCR and inserted into pcDNA6.2/Lumio using Gateway cloning. Full-length Lap2β was also inserted into the N-terminal GFP-containing vector pCDNA6.2/Dest53 using Gateway cloning. Sec61-GFP and H2B-tdTomato were previously described; in brief, a fragment of Sec61 (aa 1–65) was amplified by PCR and cloned as a C-terminal fusion to GFP, and the H2B construct was provided by G. Pearson (The Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, CA) and is a C-terminal fusion to tdTomato (Anderson and Hetzer, 2008a). Antibodies against V5 (mouse [Invitrogen] and rabbit [Novus Biologicals]), BAF (Novus Biologicals), Sun1 (Abcam), tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich), LBR (Abcam), and calreticulin (Novus Biologicals) are commercially available. Antibodies against Lap2β were provided by the laboratory of R. Foisner (Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria). Antibodies against Ndc1 were provided by the laboratory of U. Kutay (ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland; Mansfeld et al., 2006). Antibodies for Pom121 were generated in a rabbit host against aa 448–647 of murine Pom121 fused to GST. Monoclonal antibodies against the V5 epitope were used at a dilution of 1:1,000 for indirect immunofluorescence and 1:5,000 for Western blotting. Monoclonal antibodies against Lap2β were used 1:1 for both indirect immunofluorescence and Western blotting. Antibodies against BAF were used at a dilution 1:500, antibodies against LBR were used at a dilution of 1:1,000, antibodies against Sun1 were used at a dilution of 1:500, unpurified serum against Pom121 was used at a dilution of 1:500, antibodies against Nup107 were used at a dilution of 1:500, and antibodies against Ndc1 were used at a dilution of 1:500 for Western blotting.

Cell transfection and live cell imaging

U2OS cells were grown and imaged in DME with 10% fetal bovine serum with 1× antibiotic antimycotic (Invitrogen). Cells were plated on 8-well microslides (iBidi) and transfected with 0.6 µl Lipfectamine2000 (Invitrogen) and 0.3 µg of each DNA construct 2 d before live cell imaging as recommended by Invitrogen. For siRNA knockdown, cells were transfected with 25 nmol RNA 2 and 4 d before imaging. siRNA oligo sequences used were as follows: Lap2β, 5′-AGGCAUUAACUAGGGAAUdTdT-3′; LBR, LBR Stealth Select RNAi HSS105976 BAF, 5′-GGCCUAUGUUGUCCUUGGCdTdT-3′; Ndc1, 5′-CUGCACCACAGUAUUUAUA-3′; Rtn1, 5′-UAGAUGCGGAAACUGAUGGTT-3′; Rtn3, 5′-CCUUCUAAUUCUUGCUGAATT-3′; Rtn4, 5′-GAAUCUGAAGUUGCUAUATT-3′; Nup107, 5′-CUGCGAAUACACUUUCCUCTT-3′; Sun1, 5′-CCAUCCUGUAUACCUGUCUGUAU-3′; Pom121, 5′-CAGUGGCAGUGGACAUUCA-3′; and scrambled, 5′-UAGAUACCAUGCACAAUCCTT-3′ (Invitrogen). Live cells were imaged at 37°C maintained by air stream incubator and enriched with CO2 (Solent Scientific). Time-lapse images were taken on a spinning-disk confocal microscope (Yokogawa) built around an inverted stage microscope (DMRIE2; Leica). Images were captured on an EM charge-coupled device digital camera (Hamamatsu Photonics) and acquired using SimplePCI (Compix). Cells were imaged using a 63× oil emersion objective with a 1.4 numerical aperture (Leica). Fluorochromes used in this study are EGFP, tdTomato, Alexa Fluor 488, and Alexa Fluor 568.

Image analysis and statistics

Images were analyzed using Photoshop (version CS4; Adobe) extended, and statistics used were as described previously; in brief, mean pixel intensity was measured by selecting regions of interest, resulting data were analyzed in Excel (Microsoft), and distances were measured in micrometers by selection (Anderson and Hetzer, 2008a).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows confirmation of siRNA knockdown efficiencies, membrane recruitment to chromatin under knockdown conditions for various proteins, and NE/ER ratio for Lap2B-GFP at varying expression levels. Fig. S2 shows localization of epitope-tagged constructs by immunofluorescence. Tables S1–S3 show statistics for the average NE formation time for the treatments used in this study. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200901106/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maximiliano D'Angelo, Maya Capelson, Christine Doucet, Walter Eckhart, Sebastian Gomez, Tony Hunter, Yun Liang, Robbie Schulte, Jessica Talamas, Matthew Weitzman, and Susan Wente for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (award number R01GM073994).

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: BAF, barrier of autointegration factor; INM, inner nuclear membrane; LBR, lamin B receptor; LEM, Lap2/emerin/Man1; NE, nuclear envelope; NPC, nuclear pore complex; ONM, outer nuclear membrane.

References

- Anderson D.J., Hetzer M.W. 2007. Nuclear envelope formation by chromatin-mediated reorganization of the endoplasmic reticulum.Nat. Cell Biol. 9:1160–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D.J., Hetzer M.W. 2008a. Reshaping of the endoplasmic reticulum limits the rate for nuclear envelope formation.J. Cell Biol. 182:911–924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D.J., Hetzer M.W. 2008b. Shaping the endoplasmic reticulum into the nuclear envelope.J. Cell Sci. 121:137–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonin W., Ellenberg J., Dultz E. 2008. Nuclear pore complex assembly through the cell cycle: regulation and membrane organization.FEBS Lett. 582:2004–2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke B., Ellenberg J. 2002. Remodelling the walls of the nucleus.Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:487–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp M., Liu Q., Roux K., Rattner J.B., Shanahan C., Burke B., Stahl P.D., Hodzic D. 2006. Coupling of the nucleus and cytoplasm: role of the LINC complex.J. Cell Biol. 172:41–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Angelo M.A., Hetzer M.W. 2006. The role of the nuclear envelope in cellular organization.Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63:316–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dultz E., Zanin E., Wurzenberger C., Braun M., Rabut G., Sironi L., Ellenberg J. 2008. Systematic kinetic analysis of mitotic dis- and reassembly of the nuclear pore in living cells.J. Cell Biol. 180:857–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberg J., Lippincott-Schwartz J. 1999. Dynamics and mobility of nuclear envelope proteins in interphase and mitotic cells revealed by green fluorescent protein chimeras.Methods. 19:362–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberg J., Siggia E.D., Moreira J.E., Smith C.L., Presley J.F., Worman H.J., Lippincott-Schwartz J. 1997. Nuclear membrane dynamics and reassembly in living cells: targeting of an inner nuclear membrane protein in interphase and mitosis.J. Cell Biol. 138:1193–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foisner R. 2003. Cell cycle dynamics of the nuclear envelope.ScientificWorldJournal. 3:1–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K., Fritze C.E., Gerace L. 1998. The major nuclear envelope targeting domain of LAP2 coincides with its lamin binding region but is distinct from its chromatin interaction domain.J. Biol. Chem. 273:4213–4219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gant T.M., Harris C.A., Wilson K.L. 1999. Roles of LAP2 proteins in nuclear assembly and DNA replication: truncated LAP2β proteins alter lamina assembly, envelope formation, nuclear size, and DNA replication efficiency in Xenopus laevis extracts.J. Cell Biol. 144:1083–1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorjanacz M., Klerkx E.P., Galy V., Santarella R., Lopez-Iglesias C., Askjaer P., Mattaj I.W. 2007. Caenorhabditis elegans BAF-1 and its kinase VRK-1 participate directly in post-mitotic nuclear envelope assembly.EMBO J. 26:132–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi T., Koujin T., Hayakawa T., Kaneda T., Tsutsumi C., Imamoto N., Akazawa C., Sukegawa J., Yoneda Y., Hiraoka Y. 2000. Live fluorescence imaging reveals early recruitment of emerin, LBR, RanBP2, and Nup153 to reforming functional nuclear envelopes.J. Cell Sci. 113:779–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi T., Kojidani T., Koujin T., Shimi T., Osakada H., Mori C., Yamamoto A., Hiraoka Y. 2008. Live cell imaging and electron microscopy reveal dynamic processes of BAF-directed nuclear envelope assembly.J. Cell Sci. 121:2540–2554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetzer M.W., Walther T.C., Mattaj I.W. 2005. Pushing the envelope: structure, function, and dynamics of the nuclear periphery.Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21:347–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmer L., Worman H.J. 2001. Inner nuclear membrane proteins: functions and targeting.Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58:1741–1747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketema M., Wilhelmsen K., Kuikman I., Janssen H., Hodzic D., Sonnenberg A. 2007. Requirements for the localization of nesprin-3 at the nuclear envelope and its interaction with plectin.J. Cell Sci. 120:3384–3394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Lee K.K., Segura-Totten M., Neufeld E., Wilson K.L., Gruenbaum Y. 2003. MAN1 and emerin have overlapping function(s) essential for chromosome segregation and cell division in Caenorhabditis elegans.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:4598–4603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L., Ladinsky M.S., Kirchhausen T. 2009. Cisternal organization of the endoplasmic reticulum during mitosis.Mol. Biol. Cell. doi:10.1091/mbc.E09-04-0327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfeld J., Guttinger S., Hawryluk-Gara L.A., Pante N., Mall M., Galy V., Haselmann U., Muhlhausser P., Wozniak R.W., Mattaj I.W., et al. 2006. The conserved transmembrane nucleoporin NDC1 is required for nuclear pore complex assembly in vertebrate cells.Mol. Cell. 22:93–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhka M., Vihinen H., Joensuu M., Jokitalo E. 2007. Endoplasmic reticulum remains continuous and undergoes sheet-to-tubule transformation during cell division in mammalian cells.J. Cell Biol. 179:895–909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyrpasopoulou A., Meier J., Maison C., Simos G., Georgatos S.D. 1996. The lamin B receptor (LBR) provides essential chromatin docking sites at the nuclear envelope.EMBO J. 15:7108–7119 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura-Totten M., Kowalski A.K., Craigie R., Wilson K.L. 2002. Barrier-to-autointegration factor: major roles in chromatin decondensation and nuclear assembly.J. Cell Biol. 158:475–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata Y., Voeltz G.K., Rapoport T.A. 2006. Rough sheets and smooth tubules.Cell. 126:435–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somech R., Gal-Yam E.N., Shaklai S., Geller O., Amariglio N., Rechavi G., Simon A.J. 2007. Enhanced expression of the nuclear envelope LAP2 transcriptional repressors in normal and malignant activated lymphocytes.Ann. Hematol. 86:393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavru F., Hulsmann B.B., Spang A., Hartmann E., Cordes V.C., Gorlich D. 2006. NDC1: a crucial membrane-integral nucleoporin of metazoan nuclear pore complexes.J. Cell Biol. 173:509–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulbert S., Platani M., Boue S., Mattaj I.W. 2006. Direct membrane protein–DNA interactions required early in nuclear envelope assembly.J. Cell Biol. 173:469–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voeltz G.K., Rolls M.M., Rapoport T.A. 2002. Structural organization of the endoplasmic reticulum.EMBO Rep. 3:944–950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voeltz G.K., Prinz W.A., Shibata Y., Rist J.M., Rapoport T.A. 2006. A class of membrane proteins shaping the tubular endoplasmic reticulum.Cell. 124:573–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther T.C., Alves A., Pickersgill H., Loiodice I., Hetzer M., Galy V., Hulsmann B.B., Kocher T., Wilm M., Allen T., et al. 2003. The conserved Nup107-160 complex is critical for nuclear pore complex assembly.Cell. 113:195–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Q., Worman H.J. 1996. Interaction between an integral protein of the nuclear envelope inner membrane and human chromodomain proteins homologous to Drosophila HP1.J. Biol. Chem. 271:14653–14656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]