We cannot pick up a magazine or surf the Internet without facing reminders of the challenges to health care and the “sorry state” of health systems.1 All health care systems are faced with the challenges of improving quality of care and reducing the risk of adverse events.2 Globally, health systems fail to use evidence optimally. The result is inefficiency and a reduction in both quantity and quality of life.3,4 For example, McGlynn and colleagues5 found that adults in the United States received less than 55% of recommended care. Providing evidence from clinical research (e.g., through publication in journals) is necessary but not enough for the provision of optimal care. Recognition of this issue has created interest in knowledge translation, also known as KT, which we define as the methods for closing the gaps from knowledge to practice. In this series of articles, we will provide a framework for implementing knowledge for clinicians, managers and policy-makers.

What is knowledge translation?

Many terms have been used to describe the process of putting knowledge into action.6 In their work to create a search filter for knowledge translation, McKibbon and colleagues have so far identified more than 90 terms for use of research (Dr. Ann McKibbon, McMaster University: unpublished data, 2009)! In the United Kingdom and Europe, the terms implementation science or research utilization are commonly used. In the United States, the terms dissemination and diffusion, research use, and knowledge transfer and uptake are often used. In Canada, the terms knowledge transfer and exchange and knowledge translation are commonly used. Knowledge translation has been adopted in Canada because translation of research is embedded in the mandate of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (the federal agency for the funding of health research). In this series, we use the terms knowledge translation and knowledge-to-action interchangeably.

Formally, knowledge translation is defined by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research as a dynamic and iterative process that includes the synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically sound application of knowledge to improve health, provide more effective health services and products, and strengthen the health care system. This definition has been adapted by others, including the United States National Center for Dissemination of Disability Research and the World Health Organization (WHO). The common element among these different terms is a move beyond the simple dissemination of knowledge into actual use of knowledge. Knowledge creation (i.e., primary research), knowledge distillation (i.e., the creation of systematic reviews and guidelines) and knowledge dissemination (i.e., appearances in journals and presentations) are not enough on their own to ensure the use of knowledge in decision-making.

We should also clarify what knowledge translation isn’t. Some organizations may use the term synonymously with commercialization or technology transfer. But this use does not take into consideration the various stakeholders involved (including patients, health care providers and policy-makers) or the actual process of using knowledge in decision-making. Similarly, some confusion arises around the definition of continuing education versus that of knowledge translation. Educational interventions (e.g., audit and feedback, journal clubs) are a strategy for implementing knowledge. But the audience for knowledge translation is larger than the health care professionals targeted for continuing medical education or professional development. Strategies for knowledge translation may vary according to the target audience (e.g., researchers, clinicians, policy-makers, the public) and the type of knowledge being translated (i.e., clinical, biomedical or policy-related).3

Why is it important?

Failures to use evidence from research to make informed decisions in health care are evident across all groups of decision-makers, including health care providers, patients, informal caregivers, managers and policy-makers. These failures are also evident in both developed and developing countries, in both primary and specialty care and in care provided by all disciplines. Practice audits performed in a variety of settings have revealed that high-quality evidence is not being used consistently in practice.5 For example, statins are considerably underprescribed even though several randomized trials have shown that statins can reduce the risk of mortality and morbidity in poststroke patients.7,8 By contrast, antibiotics are overprescribed in children with upper respiratory tract symptoms.9 A synthesis of 14 studies showed that many patients (26%–95%) were dissatisfied with the information they received from their physicians.10

Policy-making can involve several stages, including prioritization, development, and implementation. Lavis and colleagues11 studied 8 processes for policy-making in health. They found that citable research in health services was used in at least 1 stage of the policy-making process for only 4 policies, and it was used in all stages of the process in only 1 of those 4. Similarly, evidence from systematic reviews has been found to be used infrequently by WHO policy-makers.12 Dobbins and colleagues13 observed that, although systematic reviews were used in making guidelines for public health in Ontario, the recommendations were not adopted at the level of policy.

Increasing recognition of these gaps in translating knowledge to action has led to efforts to change behaviour, practices and policy. Changing behaviour is a complex process requiring the evaluation of an entire health care organization. This evaluation includes the identification of barriers to change (e.g., lack of integrated health information systems) and targets all those involved in making decisions.3 Efforts must be made to improve health outcomes by using effective interventions to close the gaps in translating knowledge to practice. These initiatives must include all aspects of care, including access to and use of valid evidence, patient safety strategies, and organizational and systems issues.

What are its determinants?

Multiple factors influence the way research is used by different stakeholders in making decisions.14–18 A common challenge that all decision-makers (i.e., clinicians, patients, managers, policy-makers) face relates to the lack of skills in knowledge management and infrastructure (i.e., the sheer volume of research evidence currently produced, access to research evidence, time to read and the skills to appraise, understand and apply research evidence). For example, if a general internist wanted to keep abreast of the primary clinical literature relevant to this field, she would need to read 17 articles daily.19 Given that this finding was reported almost 20 years ago and that more than 1000 articles are indexed daily in MEDLINE, the number of articles the internist would need to read today would be double that estimate. In one study of the use of evidence, clinicians took more than 2 minutes to identify a Cochrane review and its relevant clinical bottom line. This resource was therefore frequently abandoned in “real-time” clinical searches.20 Lack of skills needed for appraising evidence has been a challenge to all stakeholder groups because, until recently, this skill set has not been a traditional component of most educational curricula.21,22 For example, Sekimoto and colleagues23 found that physicians in their study believed a lack of evidence for the effectiveness of a treatment was equivalent to the treatment being ineffective. Similarly, in another study, public health decision-makers identified a lack of skill in critical appraisal of evidence.24

The content of evidence resources is often not enough for the needs of the end-users. Criteria have been developed to enhance reporting of systematic reviews.25 But their focus has been on the validity of evidence rather than its applicability. For instance, when attempting to use evidence from systematic reviews for clinical decision-making, Glenton and colleagues26 found that reviews often lacked details about interventions and did not provide adequate information on the availability of interventions or the risk of adverse events. Glasziou and colleagues27 observed that, of 25 systematic reviews published over 1 year in Evidence-Based Medicine, only 3 systematic reviews contained a description of the intervention that was adequate to allow clinical decision-making and implementation. This finding was true for even “simple” interventions, such as medications.

Better management of knowledge is necessary but is not enough to ensure effective knowledge translation. Challenges exist at different levels,18 including the health care system (e.g., financial disincentives), the health care organization (e.g., lack of equipment), health care teams (e.g., local standards of care may not be in line with recommended practice), individual health care professionals (e.g., variations in knowledge, attitudes and skills in critically appraising and using evidence from clinical literature) and patients (e.g., low adherence to recommendations). Frequently, multiple challenges are present that operate at different levels of the health care system. A subsequent article in this series will tackle the barriers to knowledge translation, summarizing more than 250 barriers that have been identified.28

The knowledge-to-action framework

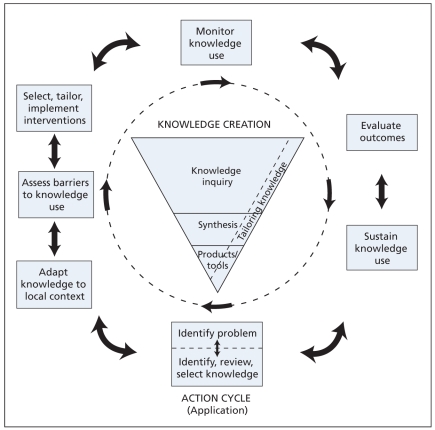

Many proposed theories and frameworks exist for the practice of knowledge translation, which can be confusing in practice.29–33 A conceptual framework developed by Graham and colleagues,6 termed the knowledge-to-action cycle, provides an approach that builds on the commonalities found in a review of planned action theories. A process of knowledge creation was added to this model. It has been adopted by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research as the accepted model for promoting the application of research and for the process of knowledge translation.

In this model, the process of translating knowledge to action is an iterative, dynamic and complex process. It concerns the creation and application (action cycle) of knowledge. Although it is drawn as a cycle, users may need to use the phases out of sequence, depending on the project. When using this process, it is essential that the end-users of the knowledge are included to ensure that the knowledge and its subsequent implementation are relevant to their needs. The funnel of knowledge creation and the major action steps or stages comprising the model for translating knowledge to action are illustrated in Figure 1.4 This series of articles will use this framework to illustrate a strategy for the practice of knowledge translation.

Figure 1.

The knowledge-to-action framework.

Knowledge creation

Knowledge creation, or the production of knowledge, is composed of 3 phases. These phases are knowledge inquiry, synthesis of knowledge and creation of knowledge tools. As knowledge is distilled through each stage in the knowledge creation process, the resulting knowledge becomes more synthesized and potentially more useful to end-users. Knowledge inquiry includes the completion of primary research. The synthesis stage brings together the disparate research findings that may exist globally on a topic and attempts to identify common patterns. Systematic reviews are the foundation of most activities related to knowledge translation, reflecting that the totality of the evidence should be considered rather than the results of individual studies. We must also consider the quality of the evidence. For example, if we are considering a management issue, ideally we need evidence from a systematic review of good-quality randomized trials. Information on adverse events may not be captured in these studies, however, so consideration of observational studies may be required. At the stage of development of tools and products, the best-quality knowledge is further synthesized and distilled into decision-making tools such as practice guidelines, aids for patient decisions or algorithms. These knowledge tools are discussed in more detail in the next article in this series.

We must be cautious of the assumption that all knowledge must be translated. We need to ensure instead that a mature and valid base of evidence exists. The realities of health care systems are that we cannot do everything and thus we must work with stakeholders (including patients and the public, clinicians and policy-makers) to establish an explicit process for prioritizing activities related to knowledge translation.

The action cycle

The 7 action phases can occur sequentially or simultaneously and the knowledge phases can influence the action phases at any point in the cycle. For example, as knowledge is updated, we may need to reconsider barriers that exist to this knowledge. The action parts of the cycle are based on theories of planned action that focus on deliberately causing change in health care systems and groups.29,30 Included are the processes needed to use knowledge in health care settings. Specifically, these processes are identifying the problem; identifying, reviewing and selecting the knowledge to implement; adapting or customizing the knowledge to the local context; assessing the determinants of knowledge use; selecting, tailoring, implementing and monitoring interventions related to knowledge translation; evaluating outcomes or impacts of using the knowledge; and determining strategies for ensuring sustained use of knowledge. Integral to the framework is the need to consider the various stakeholders (including patients, clinicians, managers or policy-makers) who are the end-users of the knowledge that is being implemented.

To illustrate this cycle, consider a local group that includes patient advocates, public health clinicians, home care clinicians and internal medicine clinicians. This group reported that many people in its region who were admitted to a local hospital with falls and fractures were not subsequently assessed for osteoporosis or risk for falls.34 Evidence from systematic reviews suggests that therapy for osteoporosis (such as bisphosphonates) can reduce the risk of fractures.35 Evidence around prevention of falls is more controversial36 but the group was interested in tackling this problem. Its members completed a local audit and found that less than 40% of patients aged 65 and older who were admitted to hospital with fractures were subsequently assessed for osteoporosis. To adapt the evidence to their context, the group created tools for patients to implement the evidence (i.e., recommending weight-bearing exercise and use of calcium and vitamin D) because many did not have a primary care physician or may not have tended to discuss this issue with their physician. The barriers to implementing these tools included the lack of an integrated health record that could be used to identify patients at risk and and a population that was spread over a large region. The group developed a multicomponent, nurse-led strategy that incorporated patient education, self-management, review of medications and assessment of homes for fall-related risks. Because the group did not know if their strategy for knowledge translation was effective, its members performed a randomized trial of the intervention. The outcomes of interest in the trial included appropriate use of osteoporosis medications and falls at 6 and 12 months. The trial also considered quality of life, patient satisfaction and fractures. Another outcome was the strength of collaboration this group developed. The group grew to include representatives from the provincial government, pharmaceutical companies and insurance companies. This example highlights the collaboration that is necessary for the practice of knowledge translation and the need to address questions that stakeholders are interested in tackling.

This series of articles uses the knowledge-to-action framework to provide an introduction to the science and practice of knowledge translation. We will present the key elements of the action cycle and outline strategies for successful knowledge translation targeted to relevant stakeholders, who include the public, clinicians, policy-makers and others. Each article was created following a systematic search of the literature and appraisal of individual studies for validity. Gaps in the literature will be identified. The science of knowledge translation is a relatively new field and we will attempt to reflect this fact, highlighting future areas of research.

Key points

Gaps between evidence and decision-making occur at all levels of health care, including those of patients, health care professionals and policy-makers.

Knowledge translation involves using high-quality knowledge in processes of decision-making.

The knowledge-to-action framework provides a model for the promotion of the application of research and the process of knowledge translation.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: Sharon Straus is an associate editor for ACP Journal Club and Evidence-Based Medicine and is on the advisory board of BMJ Group. None declared for Jacqueline Tetroe and Ian Graham.

Sharon Straus is the Section Editor of Reviews at CMAJ and was not involved in the editorial decision-making process for this article.

Contributors: All of the authors were involved in the development of the concepts in the manuscript and the drafting of the manuscript, and all of them approved the final version submitted for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Park A.Annual checkup: the sorry state of American health Time Magazine 200817241–8.Available: www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1860289_1860561_1860562,00.html(accessed 2009 Apr. 1)19058750 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis D, Evans M, Jadad A, et al. The case for knowledge translation: shortening the journey from evidence to effect. BMJ. 2003;327:33–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7405.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madon T, Hofman KJ, Kupfer L, et al. Public health. Implementation science. Science. 2007;318:1728–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1150009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the US. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majumdar SR, McAlister FA, Furberg CD. From knowledge to practice in chronic cardiovascular disease — a long and winding road. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1738–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaRosa JC, He J, Vupputuri S. Effect of statins on risk of coronary disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1999;282:2340–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnold SR, Straus SE. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices in ambulatory care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD003539. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003539.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiesler DJ, Auerbach SM. Optimal matches of patient preferences for information, decision-making and interpersonal behavior: evidence, models and interventions. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:319–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavis JN, Ross SE, Hurley JE, et al. Examining the role of health services research in public policy making. Milbank Q. 2002;80:125–54. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oxman AD, Lavis JN, Fretheim A. Use of evidence in WHO recommendations. Lancet. 2007;369:1883–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60675-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobbins M, Thomas H, O-Brien MA, Duggan M. Use of systematic reviews in the development of new provincial public health policies in Ontario. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;20:399–404. doi: 10.1017/s0266462304001278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gravel K, Legare F, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Implement Sci. 2006;1:16. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legare F, O’Connor AM, Graham ID, et al. Primary health care professionals’ views on barriers and facilitators to the implementation of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework in practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63:380–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milner M, Estabrooks CA, Myrick F. Research utilisation and clinical nurse educators: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12:639–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Walker AE, et al. Changing physician’s behaviour: what works and thoughts on getting more things to work. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2002;22:237–43. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340220408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haynes RB. Where’s the meat in clinical journals? [editorial] ACP J Club. 1993;119:A22–3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Straus SE, Sackett DL.Bringing evidence to the point of care JAMA 19992811171–2.10199421 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milner M, Estabrooks CA, Myrick F. Research utilization and clinical nurse educators: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12:639–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lavis JN. Research, public policymaking, and knowledge-translation processes: Canadian efforts to build bridges. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:37–45. doi: 10.1002/chp.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sekimoto M, Imanaka Y, Kitano N, et al. Why are physicians not persuaded by scientific evidence? A grounded theory interview study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:92. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ciliska D, Hayward S, Dobbins M, et al. Transferring public-health nursing research to health-system planning: assessing the relevance and accessibility of systematic reviews. Can J Nurs Res. 1999;31:23–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials: the QUORUM statement. Lancet. 1999;354:1896–900. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glenton C, Underland V, Kho M, et al. Summaries of findings, descriptions of interventions, and information about adverse effects would make reviews more informative. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:770–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.12.011. Epub 2006 May 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glasziou P, Meats E, Heneghan C, et al. What is missing from descriptions of treatments in trials and reviews? BMJ. 2008;336:1472–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39590.732037.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrison M, Legare F, et al. The knowledge to action cycle: adapting clinical practice guidelines to local context and assessing barriers to their use. In: Straus S, Graham I, Tetroe J, editors. Knowledge translation in health care. Oxford (UK): Wiley-Blackwell, BMJ Books, J Wiley and Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graham ID, Harrison MB, Logan J the KT Theories Research Group. A review of planned change (knowledge translation) models, frameworks and theories. Proceedings of the JBI International Convention; 2005 Nov. 28–30; Adelaide, Australia. Adelaide: JBI; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham ID, Tetroe J KT Theories Research Group. Some theoretical underpinnings of knowledge translation. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:936–41. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Estabrooks CA, Thompson DS, Lovely JJ, et al. A guide to knowledge translation theory. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:25–36. doi: 10.1002/chp.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonald KM, Graham ID, Grimshaw J. Toward a theoretic basis for quality improvement interventions. In: Shojania KG, McDonald KM, Wachter RM, et al., editors. Closing the quality gap: a critical analysis of quality improvement strategies. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. [(accessed 2009 Apr. 1)]. Vol 1 — Series overview and methodology Technical review 9 2004 (Contract No 290-02-0017 to the Stanford University-UCSF Evidence-based Practices Center). AHRQ Publication No 04-0051-1. Available: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=hstat2.chapter.26505. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wensing M, Bosch M, Foy R, et al. Factors in theories on behaviour change to guide implementation and quality improvement in healthcare. Nijmegen, the Netherlands: Centres for Quality of Care Research (WOK); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ciaschini P, Straus SE, Dolovich L, et al. Community-based randomised controlled trial evaluating falls and osteoporosis risk management strategies. Trials. 2008;9:62. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-9-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Alendronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD001155. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001155.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gates S, Fisher JD, Cooke ME, et al. Multifactorial assessment and targeted intervention for preventing falls and injuries among older people in community and emergency settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:130–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39412.525243.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]