Abstract

Rate-equilibrium free energy relationship (REFER) analysis provides information on transition-state structures and has been applied to reveal the temporal sequence in which the different regions of an ion channel protein move during a closed–open conformational transition. To date, the theory used to interpret REFER relationships has been developed only for equilibrium mechanisms. Gating of most ion channels is an equilibrium process, but recently several ion channels have been identified to have retained nonequilibrium traits in their gating cycles, inherited from transporter-like ancestors. So far it has not been examined to what extent REFER analysis is applicable to such systems. By deriving the REFER relationships for a simple nonequilibrium mechanism, this paper addresses whether an equilibrium mechanism can be distinguished from a nonequilibrium one by the characteristics of their REFER plots, and whether information on the transition-state structures can be obtained from REFER plots for gating mechanisms that are known to be nonequilibrium cycles. The results show that REFER plots do not carry information on the equilibrium nature of the underlying gating mechanism. Both equilibrium and nonequilibrium mechanisms can result in linear or nonlinear REFER plots, and complementarity of REFER slopes for opening and closing transitions is a trivial feature true for any mechanism. Additionally, REFER analysis provides limited information about the transition-state structures for gating schemes that are known to be nonequilibrium cycles.

INTRODUCTION

Rate-equilibrium free energy relationship (REFER) analysis is a methodology originally developed to characterize the energetics of simple chemical reactions (Marcus, 1968; Grunwald, 1985). Recently, this approach has been successfully applied to glean insight into the dynamics of protein conformational changes, such as the opening conformational transitions of ligand-gated ion channels (e.g., Grosman et al., 2000; Cymes et al., 2002; Chakrapani and Auerbach, 2005). Using this methodology, the relative timing of movements of different structural regions of the channel protein can be deduced (Zhou et al., 2005; Auerbach, 2007). So far, REFER analysis has been applied to reversible systems that are known to be at thermodynamic equilibrium.

For the majority of ion channels, gating is assumed to be an equilibrium process, in contrast to transporters that use an external source of energy to complete their catalytic cycles. As a consequence, ion channel biophysicists generally do not encounter irreversible or nonequilibrium mechanisms. However, some channel and transporter mechanisms have lately been found to intersect, suggesting that evolutionary divergence from common ancestors has given rise to related families of channels and transporters (Gadsby et al., 2006; Miller, 2006; Chen and Hwang, 2008; Csanády and Mindell, 2008; Gadsby, 2009). Channels with transporter-like features and transporters with channel-like features are more abundant than previously envisaged. One such example is CFTR, a chloride ion channel that belongs to the ABC transporter superfamily (Riordan et al., 1989). Transport function of ABC proteins is linked to ATP hydrolysis and is hence a nonequilibrium process (Higgins, 2001; Oldham et al., 2008). Likewise, gating of the CFTR channel pore has been linked to ATP hydrolysis (Gunderson and Kopito, 1994; Hwang et al., 1994) and has been found to violate microscopic reversibility (Gunderson and Kopito, 1995; Ishihara and Welsh, 1997; Zeltwanger et al., 1999), implying a nonequilibrium mechanism. Members of the Clc channel/transporter superfamily provide another example; Clc chloride channels appear to have evolved from ancestral transporters, and violations of microscopic reversibility in Clc channel gating (Richard and Miller, 1990; Pusch et al., 1995; Chen and Miller, 1996; Chen et al., 2003; Miller, 2006; Chen and Hwang, 2008; Lísal and Maduke, 2008) suggest that these channels have also retained vestiges of their ancestors’ nonequilibrium conformational cycles.

The success of REFER studies on ligand-gated ion channels has encouraged its recent application to CFTR channel gating (Scott-Ward et al., 2007; Aleksandrov et al., 2009). Although CFTR is indisputably an ABC protein, whether CFTR gating is a nonequilibrium process is still heavily debated, and some earlier studies were argued to provide evidence for its equilibrium nature (Aleksandrov and Riordan, 1998; Aleksandrov et al., 2000). Most recently, linear REFER plots and complementary REFER slopes for opening and closure of CFTR have been interpreted to provide further support for this notion, and to rule out a nonequilibrium mechanism (Aleksandrov et al., 2009).

At a time when the channel–transporter boundary is broadening, it might be useful to researchers working at the margin between these two families of transport proteins to examine some of the basic thermodynamic features of nonequilibrium schemes. By deriving the analytical form of the Brønsted plots for the simplest cyclic gating mechanism, a three-state model, this paper examines whether (1) a mechanism can be identified as equilibrium or nonequilibrium from the characteristics of REFER plots, and (2) whether information on the transition-state structures can be obtained from REFER plots for gating mechanisms that are known to be obligatory cycles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reaction rates are assumed to conform to transition-state theory. Thus, a rate k is obtained as

| (1) |

where ΔG‡ reflects the height of the free energy barrier (the transition-state T‡, for the C to O transition; see Fig. 2 A). Classical REFER analysis is based on the assumption that the energetic perturbation of the transition state is a linear combination of the energetic perturbations of the ground states (Marcus, 1968; Grunwald, 1985). Thus, if a structural perturbation changes the free energy of the open ground state (relative to the closed ground state) by δΔGO, then the free energy of the transition state will change by ΦδΔGO (Fig. 2 A, dashed line). As a consequence, the logarithms of the forward and backward rate constants (kCO and kOC; Fig. 1 A) will change by −ΦδΔGO/(RT) and −(Φ−1)δΔGO/(RT), respectively, whereas the logarithm of the equilibrium constant changes by −δΔGO/(RT). REFER plots (Brønsted plots) are log-log plots of forward or backward rates as a function of the equilibrium constant for a series of structural perturbations typically introduced into a single region of a protein. For Scheme 1 in Fig. 1 A, the slopes of these plots will be Φ and Φ−1, respectively, allowing experimental determination of Φ. Based on the above simple picture, a high Φ value (close to 1) indicates that in the transition state, the perturbed region of the protein is already near its open-state conformation, whereas a Φ value close to 0 is an indication that the region is still closed-like in the transition state.

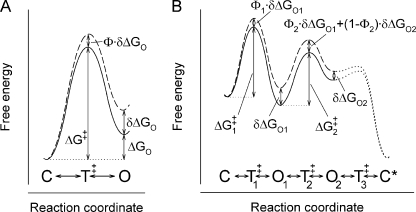

Figure 2.

Free energy landscapes for a simple equilibrium and a simple nonequilibrium gating scheme. (A) Free-energy landscape for the mechanism in Scheme 1; the reversible, equilibrium transition C↔T‡↔O is shown without (solid line) and after (dashed line) a structural perturbation. T‡ denotes the transition state. (B) Free-energy landscape for an observable closed→open→closed transition based on the mechanism in Scheme 2; landscapes without (solid line) and after (dashed line) a structural perturbation are shown. T‡1 and T‡2 denote the transition states for the C→O1 and the O1→O2 transition, respectively. T‡3, the transition state for step O2→C, reflects a low energetic barrier compared with T‡2, and has therefore little effect on closing rate (dotted lines). Irreversibility is a consequence of unequal barrier heights for exiting each of the ground states in the forward versus backward direction. Notation C* emphasizes that after each closure, the entire system has changed relative to the pre-open situation (e.g., 1 ATP has been converted to ADP+P), even though the channel protein itself has adopted its pre-open conformation (C).

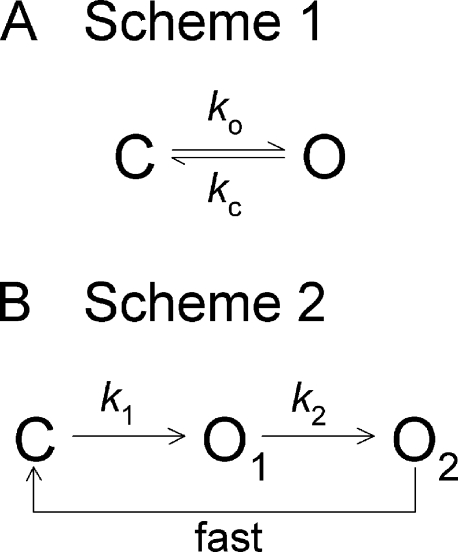

Figure 1.

A simple equilibrium and simple nonequilibrium gating scheme. (A) Simple equilibrium gating scheme (Scheme 1) with opening (ko) and closing rates (kc) reflecting forward and backward passage across the same free energy barrier. (B) Simple nonequilibrium gating scheme (Scheme 2). Because transition O2→C is fast compared with transition O1→O2, channel closing rate is determined by the rate of the latter transition (k2).

For simplicity, this study assumes the above simple barrier model and classical interpretation of the Φ value. In reality, energy landscapes for ion channel gating transitions are likely more complex, but recent work has shown that for such reactions, experimental Φ values still reflect the temporal sequence in which different regions of the protein move during a closed–open transition (Zhou et al., 2005; Auerbach, 2007). To what extent are the results presented here (Eqs. 5–20) applicable to such situations? Note that Eqs. 10 and 11, although derived here using classical simple energy barriers (Fig. 2 B and Eqs. 5–9), can be equivalently written as and , where Keq(C-O1) and Keq(O1-O2) are the equilibrium constants for steps C-O1 and O1-O2, respectively (although the system is not at equilibrium, these constants do exist). Thus, Eqs. 10 and 11—and all the equations that follow (Eqs. 12–20)—really only require that for both steps the logarithm of the forward rate constant be approximately linearly related to the logarithm of the equilibrium constant. The conclusions of this study therefore rely only on this typically observed empirical relationship, not on the actual physical interpretation of the Φ value.

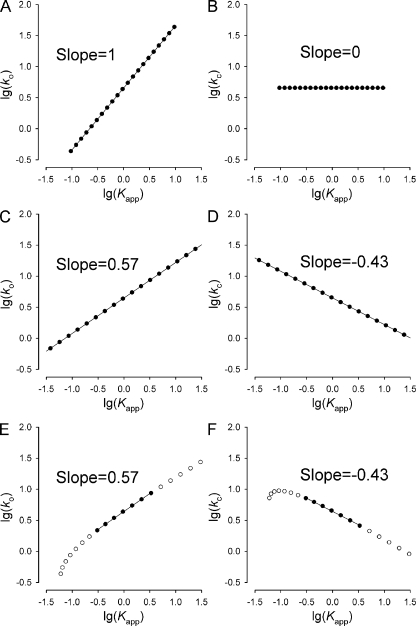

The REFER plots for Scheme 2 in Fig. 1 B, shown in Fig. 3, were calculated using Eqs. 14–16 (or Eqs. 10–12 in Fig. 3, E and F), for δΔGO1 values ranging from −2 to +2 RT (in 0.2-RT increments). Linear regression (Fig. 3, solid lines) across either the entire set (Fig. 3, A–D) or a restricted set (Fig. 3, E and F, solid symbols) of these data points was used to obtain slope factors.

Figure 3.

Calculated REFER plots for Scheme 2. Unperturbed opening and closing rates were ko = 4.348 s−1 and kc = 4.545 s−1, and Φ-values were Φ1 = 0.5 and Φ2 = 0.5. (A–D) REFER plots for opening (A and C) and closure (B and D) under the assumption of Eq. 13. In A and B, a = 1, and in panels C and D, a = 0.25. Values for logko′ and logkc′ were calculated for δΔGO1 ranging from −2 to +2 RT (in 0.2-RT increments) using Eqs. 14 and 15, and plotted as a function of logKapp′ calculated using Eq. 16. Solid lines are linear regressions to the plots, and fitted slope values are printed in each panel. (E and F) REFER plots for opening (E) and closure (F), assuming the arbitrary nonlinear relationship . Values for logko′ and logkc′ were calculated for δΔGO1 ranging from −2 to +2 RT (in 0.2-RT increments) using Eqs. 10 and 11, and plotted as a function of logKapp′ calculated using Eq. 12. Solid symbols correspond to δΔGO1 values of −0.6 RT, −0.4 RT, −0.2 RT, 0, +0.2 RT, +0.4 RT, and +0.6 RT. Solid lines are linear regressions through this restricted set of data points, and fitted slope values are printed in each panel. (In all panels, the more conventionally used log-log plots are shown instead of the natural logarithms used in Eqs. 14–16. This transformation affects neither the slopes nor the shapes of the plots.)

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This study compares a cyclic mechanism (Fig. 1 B, Scheme 2) with a two-state equilibrium mechanism (Fig. 1 A, Scheme 1). It must be emphasized that, mechanistically, three states are minimally required for a nonequilibrium reaction cycle. Although, kinetically, two-state cyclic models can be constructed assuming two states connected by two distinct pathways, such models are necessarily simplifications that, for kinetic reasons, neglect intermediate state(s) along one or both of those pathways. (e.g., kinetically, Scheme 2 also behaves as a two-state system because the short-lived O2 state can be lumped into state C.) Here, Scheme 1 is assumed to be a true mechanistic two-state model.

Can a reversible, equilibrium scheme be inferred from complementarity of REFER slopes for opening and closure?

For the simple reversible Scheme 1 in Fig. 1 A, the slopes of the Brønsted plots for opening (Φo) and closure (Φc) are “complementary” to each other in the sense that Φc = Φo − 1 (see Materials and methods). But is this feature unique to reversible schemes? Let us consider an arbitrary gating scheme that may or may not include irreversible steps. Suppose the current of a single channel is recorded for some length of time T, during which the channel produces n openings and closures of duration to1, tc1,…ton, tcn, respectively. Mean open time (τo) and mean closed time (τc) and open probability (Po) are then obtained as

Because

the previous equation can be rewritten as

| (2) |

This simple relationship between mean open times, mean closed times, and open probability (Eq. 2) is fundamentally true for any gating scheme, reversible or irreversible, and therefore, in contrast to published suggestions (Aleksandrov and Riordan, 1998; Aleksandrov et al., 2009), provides no evidence concerning the mechanism of CFTR channel gating.

What is the corollary of Eq. 2 for REFER analysis? Using mean opening and closing rates, defined as the inverses of the mean closed and open times (ko = 1/τc, kc = 1/τo), Eq. 2 can be rewritten as

| (3) |

Let us formally define Kapp = Po/(1−Po). If the process is reversible, then Kapp is the apparent equilibrium constant between the set of open states and the set of closed states; if the process is far from equilibrium, and hence effectively irreversible, then Kapp has no physical meaning. Nonetheless, for both cases it follows from Eq. 3 that Kapp = ko/kc, i.e., ln Kapp = lnko − lnkc. For any functions f1, f2, and F = f1 − f2, it necessarily follows that

Therefore, by necessity,

| (4) |

In other words, the slopes of the REFER plots for opening (Φo,app) and closure (Φc,app) will always follow the “complementarity” described above for Scheme 1 (i.e., Φc,app = Φo,app − 1), whether or not a gating scheme contains irreversible steps. Ultimately, the relationship in Eq. 4 is a reflection of the fact that every ion channel—regardless of the mechanism that operates its gates—spends complementary fractions of time open versus closed. Demonstration that this relationship holds therefore cannot be interpreted as providing evidence to support an equilibrium mechanism of gating of the CFTR channel (compare with Aleksandrov et al., 2009).

Does an equilibrium mechanism guarantee linearity of REFER plots?

Experimental REFER plots for ligand-gated ion channels have so far been found to be mostly linear (e.g., Grosman et al., 2000; Chakrapani et al., 2004, but, compare with Mitra et al., 2005). But is this linearity attributable to the known equilibrium nature of their gating mechanisms? There is certainly no theoretical requirement for REFER plots to be linear for equilibrium schemes, and the original theory, which assumed barrier functions to be simple intersecting parabolas (Marcus, 1968), predicts REFER plots to be quadratic (the predicted negative curvature is known as the Hammond effect). The linearity assumption is a first-order approximation, assumed to be valid for small perturbations.

Recent studies have concluded that the opening/closing transition of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channel reflects sequential passage through a series of short-lived intermediate states, too brief to be detected in patch clamp recordings (Auerbach, 2005; Zhou et al., 2005). Such transition-state ensembles are best described by broad flat energy barriers that contain multiple shallow wells. Passage across such barriers requires first reaching the high-energy plateau, and then leaving the plateau in the forward direction after a random walk across the series of shallow wells. Thus, several successful attempts to reach the high-energy plateau are typically required to traverse it. Mathematical description of such reversible systems predicts REFER plots with substantial curvature, in fact more than has been observed experimentally (Zhou et al., 2005). Thus, linearity of the majority of REFER plots observed to date is not a consequence of the reversible, equilibrium nature of the underlying mechanisms.

Can an equilibrium mechanism be inferred from linear REFER plots?

Although much recent effort has been devoted to better understanding REFER data for ion channel gating, these efforts have focused on reversible, equilibrium mechanisms. As a first step to examine what can be learned about nonequilibrium mechanisms using this methodology, this section derives the REFER relationships for the simplest possible cyclic scheme, a three-state model (Fig. 1 B, Scheme 2).

Of note, Scheme 2 represents a simplified version of the cyclic gating scheme used by several groups to describe open burst/closed interburst cycles of the CFTR chloride channel (for review see Gadsby et al., 2006 and Hwang and Sheppard, 2009), in contrast to a Scheme 1–like equilibrium suggested by others (Aleksandrov and Riordan, 1998; Aleksandrov et al., 2000, 2007, 2009). Apart from its unique regulatory domain, CFTR conforms to typical ABC protein architecture, comprising two transmembrane domains (which in CFTR form the channel pore), and two intracellular nucleotide binding domains (NBDs; NBD1 and NBD2). Upon ATP binding, ABC NBDs form tight dimers, rapid disruption of which requires prior hydrolysis of at least one of the two ATP molecules buried at the dimer interface (Moody et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2002; Janas et al., 2003; Verdon et al., 2003). For CFTR, there is strong evidence that NBD dimer formation and dissociation are tightly coupled to pore opening and closure (Vergani et al., 2005). Thus, in Scheme 2, transition C→O1 represents formation of the NBD1-NBD2 heterodimer, transition O1→O2 represents hydrolysis of ATP at the NBD2 catalytic site, and transition O2→C represents rapid dissociation of the NBD dimer after ATP hydrolysis. Although ultimately all three steps are reversible, reverse rates O1→C, O2→O1, and C→O2 are neglected because evidence suggests that they are much slower than the forward rates, at least for rates O1→C and C→O2 (e.g., Vergani et al., 2005; Csanády et al., 2006). At saturating [ATP], the closed interburst states are lumped into a single, fully liganded state (C).

The free-energy landscape for such a mechanism is somewhat unusual (Fig. 2 B). During each open→close burst cycle, one molecule of ATP is converted to ADP plus phosphate and, therefore, the system does not return to the same ΔG level it experienced before opening (compare states C* vs. C in Fig. 2 B). Also, opening followed by closure reflects transitions across two distinct ΔG barriers, ΔG‡1 and ΔG‡2 (Fig. 2 B). Because rate O2→C is fast compared with rate O1→O2, closure is rate-limited by transition across the barrier O1→O2 (rate k2). Therefore, the rates of opening to, and closing from, a burst can be written as

| (5) |

| (6) |

and the apparent equilibrium constant is

| . |

Suppose a perturbation alters the free energies of the open ground states O1 and O2 (relative to the free energy of the preceding closed state) by δΔGO1 and δΔGO2, and that the conventional REFER assumption holds, i.e., that the consequent changes in barrier heights are linear combinations of the free energy changes of the ground states that the barriers separate (Fig. 2 B, dashed line). Then the perturbed barrier height for opening will be , and that for closure

(Fig. 2 B). Correspondingly, the modified opening and closing rates and apparent equilibrium constant will become

| (7) |

| (8) |

and

| (9) |

Thus, for the general case, the logarithms of the above parameters can be written as

| (10) |

| (11) |

and

| (12) |

To construct REFER plots, a series of perturbations are introduced into a single region of the protein (e.g., a series of mutations of a given amino acid residue), which will result in a series of different δΔGO1 and δΔGO2 values. The resulting lnko’ and lnkc’ values are then plotted as a function of lnKapp’. From Eqs. 10–12, it is clear that the slopes of these REFER plots will depend on the relative extent by which mutations of a given residue destabilize the O1 and O2 ground states.

Let us first consider the simple (but not unrealistic) situation in which the energetic perturbations of the O1 and O2 ground states, caused by mutations of a given residue, are proportional to each other, i.e.,

| (13) |

In this case, Eqs. 10–12 become

| (14) |

| (15) |

and

| (16) |

From Eqs. 14–16, it is clear that in this case the Brønsted plots will be linear, with slopes

| (17) |

and

| (18) |

From Eqs. 17 and 18, it is easy to see that the obligate complementarity Φc,app = Φo,app − 1 obviously applies. The panels in Fig. 3 (A–D) show calculated REFER plots for Scheme 2 under the assumption given in Eq. 13; in A and B, a = 1 (i.e., δΔGO1 = δΔGO2), and in C and D, a = 0.25. The plots were constructed for δΔGO1 values ranging from −2 to +2 RT (in 0.2-RT increments) using Eqs. 14–16, and fitted by linear regression (solid lines). The fitted slopes in each case returned the values predicted by Eqs. 17 and 18.

Thus, Scheme 2 with the assumption in Eq. 13 provides an example of a nonequilibrium scheme that generates linear REFER plots. Because a single counterexample is sufficient to invalidate a hypothesis, we can conclude that the nature (equilibrium vs. nonequilibrium) of the underlying mechanism cannot be inferred from linearity of the REFER plots (compare with Aleksandrov et al., 2009).

In the more general case, the energetic perturbations of the O1 and O2 ground states, caused by mutations of a given residue, need not be proportional to each other (Eq. 13 does not necessarily apply). However, if at least some kind of correlation exists between δΔGO2 and δΔGO1, described by some arbitrary nonlinear function , then for small perturbations the first-order approximation

| (19) |

will still be applicable. Thus, the REFER plots will be close-to-linear in some range around lnKapp’ = lnKapp, with slopes given by Eqs. 17 and 18, with the substitution a = g′(0). Whether deviations from linearity can be experimentally observed in such situations will depend on the curvature of the REFER plots and on the experimentally testable range of Kapp’. Fig. 3 (E and F) shows calculated REFER plots for opening (Fig. 3 E) and closure (Fig. 3 F) for Scheme 2, assuming the entirely arbitrary nonlinear relationship . Although these plots are substantially nonlinear, the curvatures are little apparent for an ∼10-fold range of Kapp’ values (for logKapp’ between ∼−0.5 and ∼+0.5; solid symbols). Note, because g′(0) = 0.25 in this case, linear regressions through the data points of this restricted range returned slope values identical to those in Fig. 3 (C and D).

What can be learned about the transition-state structures for a cyclic scheme?

Inspecting Eq. 17, one might hope that the observable REFER slope Φo,app might carry some information on the two transition-state structures of Scheme 2, i.e., on Φ1 and Φ2. Expressing Φ1 from Eq. 17 yields

| (20) |

Because neither Φ2 nor a are known, the REFER slopes will provide no information on the true transition states for all but two limiting cases. One limiting situation is if the observed REFER slope for opening is unity (Φo,app = 1); this implies (Eq. 17) that either Φ2 = 1 or a = 1 (in both cases the energetic perturbation of the O1→O2 transition state equals that of the O1 ground state), whereas the value of Φ1 remains undefined. The other limiting situation is Φo,app = 0; this implies (Eq. 17) that Φ1 = 0 (in the C→O1 transition state, the conformation of the studied residue still resembles its conformation in the C ground state), whereas Φ2 remains undefined.

Conclusions

The above simple examples clearly demonstrate that the characteristics of REFER plots do not carry information on reversibility or irreversibility of the underlying gating mechanism, given that both reversible and irreversible mechanisms can result in either linear or nonlinear REFER plots, whereas the complementarity (in the sense defined by Eq. 4) is a trivial feature true for any mechanism. Additionally, only very limited information about the transition-state structures can be obtained by REFER analysis for gating schemes that are known to be irreversible.

Acknowledgments

I thank David Gadsby for constructive comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01-DK051767, NIH Fogarty International Center grant R03-TW007829, and Wellcome Trust grant 081298/Z/06/Z. L. Csanády is a Bolyai Research Fellow of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Edward N. Pugh Jr. served as editor.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: NBD, nucleotide binding domain; REFER, rate-equilibrium free energy relationship.

References

- Aleksandrov A.A., Riordan J.R. 1998. Regulation of CFTR ion channel gating by MgATP.FEBS Lett. 431:97–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrov A.A., Chang X., Aleksandrov L., Riordan J.R. 2000. The non-hydrolytic pathway of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator ion channel gating.J. Physiol. 528:259–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrov A.A., Aleksandrov L.A., Riordan J.R. 2007. CFTR (ABCC7) is a hydrolyzable-ligand-gated channel.Pflugers Arch. 453:693–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrov A.A., Cui L., Riordan J.R. 2009. Relationship between nucleotide binding and ion channel gating in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator.J. Physiol. 587:2875–2886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach A. 2005. Gating of acetylcholine receptor channels: brownian motion across a broad transition state.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:1408–1412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach A. 2007. How to turn the reaction coordinate into time.J. Gen. Physiol. 130:543–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani S., Auerbach A. 2005. A speed limit for conformational change of an allosteric membrane protein.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:87–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani S., Bailey T.D., Auerbach A. 2004. Gating dynamics of the acetylcholine receptor extracellular domain.J. Gen. Physiol. 123:341–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.Y., Hwang T.C. 2008. CLC-0 and CFTR: chloride channels evolved from transporters.Physiol. Rev. 88:351–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.Y., Miller C. 1996. Nonequilibrium gating and voltage dependence of the ClC-0 Cl- channel.J. Gen. Physiol. 108:237–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.Y., Chen M.F., Lin C.W. 2003. Electrostatic control and chloride regulation of the fast gating of ClC-0 chloride channels.J. Gen. Physiol. 122:641–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csanády L., Mindell J.A. 2008. The twain shall meet: channels, transporters and things between. Meeting on Membrane Transport in Flux: the Ambiguous Interface Between Channels and Pumps.EMBO Rep. 9:960–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csanády L., Nairn A.C., Gadsby D.C. 2006. Thermodynamics of CFTR channel gating: a spreading conformational change initiates an irreversible gating cycle.J. Gen. Physiol. 128:523–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cymes G.D., Grosman C., Auerbach A. 2002. Structure of the transition state of gating in the acetylcholine receptor channel pore: a phi-value analysis.Biochemistry. 41:5548–5555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby D.C. 2009. Ion channels versus ion pumps: the principal difference, in principle.Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10:344–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby D.C., Vergani P., Csanády L. 2006. The ABC protein turned chloride channel whose failure causes cystic fibrosis.Nature. 440:477–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosman C., Zhou M., Auerbach A. 2000. Mapping the conformational wave of acetylcholine receptor channel gating.Nature. 403:773–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald E. 1985. Structure-energy relations, reaction mechanism, and disparity of progress of concerted reaction events.J. Am. Chem. Soc. 107:125–133 [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson K.L., Kopito R.R. 1994. Effects of pyrophosphate and nucleotide analogs suggest a role for ATP hydrolysis in cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator channel gating.J. Biol. Chem. 269:19349–19353 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson K.L., Kopito R.R. 1995. Conformational states of CFTR associated with channel gating: the role ATP binding and hydrolysis.Cell. 82:231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins C.F. 2001. ABC transporters: physiology, structure and mechanism—an overview.Res. Microbiol. 152:205–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T.C., Sheppard D.N. 2009. Gating of the CFTR Cl- channel by ATP-driven nucleotide-binding domain dimerisation.J. Physiol. 587:2151–2161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T.C., Nagel G., Nairn A.C., Gadsby D.C. 1994. Regulation of the gating of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator C1 channels by phosphorylation and ATP hydrolysis.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:4698–4702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara H., Welsh M.J. 1997. Block by MOPS reveals a conformation change in the CFTR pore produced by ATP hydrolysis.Am. J. Physiol. 273:C1278–C1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janas E., Hofacker M., Chen M., Gompf S., van der Does C., Tampé R. 2003. The ATP hydrolysis cycle of the nucleotide-binding domain of the mitochondrial ATP-binding cassette transporter Mdl1p.J. Biol. Chem. 278:26862–26869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lísal J., Maduke M. 2008. The ClC-0 chloride channel is a ‘broken’ Cl-/H+ antiporter.Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15:805–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R.A. 1968. Theoretical relations among rate constants, barriers, and Brønsted slopes of chemical reactions.J. Phys. Chem. 72:891–899 [Google Scholar]

- Miller C. 2006. ClC chloride channels viewed through a transporter lens.Nature. 440:484–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra A., Tascione R., Auerbach A., Licht S. 2005. Plasticity of acetylcholine receptor gating motions via rate-energy relationships.Biophys. J. 89:3071–3078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody J.E., Millen L., Binns D., Hunt J.F., Thomas P.J. 2002. Cooperative, ATP-dependent association of the nucleotide binding cassettes during the catalytic cycle of ATP-binding cassette transporters.J. Biol. Chem. 277:21111–21114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham M.L., Davidson A.L., Chen J. 2008. Structural insights into ABC transporter mechanism.Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18:726–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusch M., Ludewig U., Rehfeldt A., Jentsch T.J. 1995. Gating of the voltage-dependent chloride channel CIC-0 by the permeant anion.Nature. 373:527–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard E.A., Miller C. 1990. Steady-state coupling of ion-channel conformations to a transmembrane ion gradient.Science. 247:1208–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan J.R., Rommens J.M., Kerem B., Alon N., Rozmahel R., Grzelczak Z., Zielenski J., Lok S., Plavsic N., Chou J.L., et al. 1989. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA.Science. 245:1066–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Ward T.S., Cai Z., Dawson E.S., Doherty A., Da Paula A.C., Davidson H., Porteous D.J., Wainwright B.J., Amaral M.D., Sheppard D.N., Boyd A.C. 2007. Chimeric constructs endow the human CFTR Cl- channel with the gating behavior of murine CFTR.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:16365–16370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P.C., Karpowich N., Millen L., Moody J.E., Rosen J., Thomas P.J., Hunt J.F. 2002. ATP binding to the motor domain from an ABC transporter drives formation of a nucleotide sandwich dimer.Mol. Cell. 10:139–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdon G., Albers S.V., van Oosterwijk N., Dijkstra B.W., Driessen A.J., Thunnissen A.M. 2003. Formation of the productive ATP-Mg2+-bound dimer of GlcV, an ABC-ATPase from Sulfolobus solfataricus.J. Mol. Biol. 334:255–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergani P., Lockless S.W., Nairn A.C., Gadsby D.C. 2005. CFTR channel opening by ATP-driven tight dimerization of its nucleotide-binding domains.Nature. 433:876–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeltwanger S., Wang F., Wang G.T., Gillis K.D., Hwang T.C. 1999. Gating of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channels by adenosine triphosphate hydrolysis. Quantitative analysis of a cyclic gating scheme.J. Gen. Physiol. 113:541–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Pearson J.E., Auerbach A. 2005. Phi-value analysis of a linear, sequential reaction mechanism: theory and application to ion channel gating.Biophys. J. 89:3680–3685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]