Abstract

Purpose

Lithotripters with two treatment heads deliver shock waves (SW) along separate paths. Firing one head then the other (alternating mode) has been suggested as a strategy to treat stones twice as fast as in conventional shock wave lithotripsy (SWL). Because SW rate is known to play a role in SWL-induced injury, and given that treatment using two separate SW sources exposes more renal tissue to SW energy than treatment with a conventional lithotripter, we assessed renal trauma in pigs following treatment at rapid rate (240 SW/min, 120 SWs/min/head) using a Direx Duet lithotripter fired in alternating mode.

Methods

Adult pigs were treated with sham SWL (n=8) or 2400 SWs delivered in alternating mode (1200 SWs/head, 120 SWs/min/head, 240 SWs/min/overall, power level 10, n=8) to the lower renal pole. Renal functional parameters, including glomerular filtration rate and effective renal plasma flow, were determined before and 1hr post-SWL. The kidneys were perfusion fixed in situ and the hemorrhagic lesion quantified as percentage functional renal volume (FRV).

Results

SW treatment resulted in no significant change in renal function, and was similar to the functional response seen in sham SW-treated animals. For pigs treated in alternating mode the renal lesion was small and measured 0.22 ± 0.09% FRV (mean ± SEM, n=6).

Conclusions

Kidney tissue and function were minimally affected by a clinical dose of SWs delivered in alternating mode (120 SWs/min/head, 240 SWs/min overall) with the Duet lithotripter. These observations reduce the concern that dual-head lithotripsy at fast rate is inherently dangerous.

Keywords: kidney, lithotripsy

Introduction

New concepts in lithotripter design have emerged that include delivery of shock waves (SWs) from dual treatment heads.1–5 Direx has built the Duet lithotripter that has two independent spark-plug generator/reflector systems at a 72° angle to each other such that SWs from each treatment head converge at a common focal point. This machine is approved in the United States for patient treatment in synchronous/simultaneous (both heads fired simultaneously) or asynchronous/alternating (firing alternates between the two heads) modes at up to 120 SWs/min/head. A potential benefit of dual-head firing in alternating mode is that the stone can be exposed to 240 SWs/min and, thus, a given dose of SWs can be delivered in half the time.

Safety is an important issue in shock wave lithotripsy (SWL). Numerous reports have described SW-induced renal trauma in patients, and there is a growing awareness of a link between acute tissue damage and the potential for long-term adverse effects.6–9 Studies with experimental animals have characterized acute SWL trauma as primarily a vascular lesion that can trigger an inflammatory response leading to parenchymal scarring and loss of functional renal mass.10,11 The hemorrhagic lesion is focal in the sense that tissue damage is most pronounced in the region of the kidney targeted by the focal volume. That is, injury occurs along the acoustic axis—along the path of the SW through the kidney. In SWL with a conventional lithotripter, this can be seen to produce tissue damage extending from the renal papilla through the full thickness of the medulla and cortex.10,11 In treatment using a dual head lithotripter, SWs follow two separate paths through the kidney, raising the possibility that a greater volume of kidney tissue may be subjected to injury.

Rate of SW administration has emerged as a potentially important factor in SWL injury. Very fast SW-rate has been shown in experimental animals to enhance injury,12,13 and recent work has demonstrated that slowing the SW-rate to 30 SWs/min significantly reduces lesion volume compared to treatment at 120 SWs/min.14 With this in mind it seems important to assess the safety of SW exposure at the increased rate (240 SWs/min) that occurs with dual head lithotripsy in alternating mode.

The present study provides the first report of the renal bioeffects of a clinical dose of SWs delivered in asynchronous/alternating mode from the Direx Duet lithotripter to an established in vivo porcine model that is commonly used in SW research.15,16

Methods and Materials

Adult female pigs (45 kg; Hardin Farms, Danville, Indiana) were rendered unconscious with an intramuscular injection of ketamine (15–20 mg/kg) and xylazine (2 mg/kg), and anesthesia maintained with 1–3% isoflurane and 100% oxygen. The animals were prepared for renal function measurements as previously described and included placement of catheters into the ear vein for the intravenous infusion of fluids, the infrarenal aorta for blood pressure and heart rate monitoring and arterial blood sampling, both renal veins for renal venous blood sampling and both ureters for the collection of urine.16 Saline (150 mmol/L) was infused intravenously at 1% of body weight per hour throughout the experiment to maintain adequate hydration and urine flow.

Experimental Protocol for the Direx Duet lithotripter

The pig was in a supine position on the adjustable treatment table of the Duet lithotripter. Baseline cardiovascular and renal function measurements were begun 30 min following the completion of all surgery and coupling - with castor oil - of the pig to the SW generator heads of the lithotripter, and consisted of two 25-min clearances. The lithotripter was targeted on the lower pole calyx of the left kidney with the aid of fluoroscopy and a small amount of contrast medium injected through the left ureteral catheter. Animals were subjected to no SWs (Group 1, n=8), or 2400 SWs (Group 2, 1200 SWs/head, 120 SWs/min/head, 240 SWs/min overall, power level 10, n=8) as is recommended for clinical treatment in alternating mode. Lithotripsy was temporarily halted every 500 SWs to confirm targeting. Three 25-min clearances were then obtained following a 30-min post-lithotripsy recovery period.

Renal Function Measurements

Inulin and para-aminohippuric acid (PAH) were intravenously administered as a bolus followed by an infusion at 70 ml/h to achieve steady state plasma concentrations of 20 mg/dL and 2 mg/dL, respectively. Plasma and urine samples were analyzed for inulin and PAH, and their renal clearances used as estimates of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and effective renal plasma flow (ERPF), respectively. The renal extraction of PAH (EPAH) was calculated from the formula: ([PAH]arterial − [PAH]renal venous)/[PAH]arterial multiplied by 100, and provides an estimate of the efficiency of renal tubular organic anion transport.16

Morphological analysis

The kidneys were perfusion-fixed in situ at the end of the experiment and removed for histological and quantitative morphological analysis as previously described.17 Hemorrhagic regions within the parenchyma were identified and expressed as a percentage of functional renal volume (FRV) using computer-assisted segmentation of digital images from serial sections (120 μm) of the entire kidney. The smallest lesion that can be accurately measured with this system is 0.1% FRV.

In vitro stone breakage studies

Experiments were conducted in a test tank fitted with two latex acoustic windows that were coupled to the treatment heads using castor oil.18 The tank was filled with tap water, which was then degassed with a pinhole degasser to maintain the gas content at about 2 mg/l (~20% of saturation). The focal point of the lithotripter was identified using the alignment stylus of the Duet and then marked by crossed lasers. All studies were conducted with artificial U30 gypsum stones placed in a 2 mm mesh metal wire basket positioned at the focal point.19 SWs were administered in alternating (asynchronous) mode [120 SWs/min/head, 240 SWs/min, power level 10, n=26 stones] or in simultaneous (synchronous) mode (dual SWs at 120 SWs/min/head, power level 5, n=20 stones), and stone breakage was assessed by counting the number of SWs needed to remove all stone material from the basket. Different power settings were used in the two modes (power level 10 for alternating mode, power level 5 for simultaneous mode), as these are the settings recommended for clinical treatment.

Statistical Analysis

All values quoted represent mean ± SEM. Comparison of renal function within and across groups employed 2-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures. Stone breakage analysis used unpaired Student’s t-tests. Differences between means were considered significant at the 5% level.

Results

Cardiovascular measurements

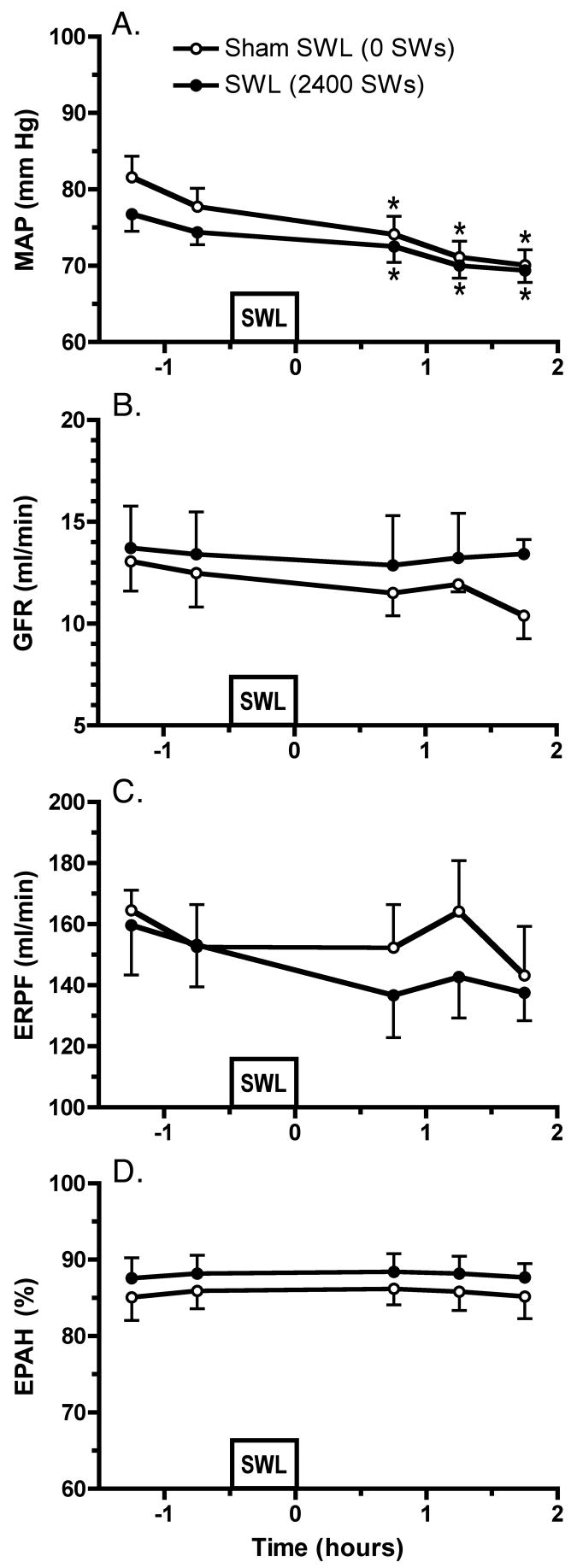

Blood pressure and renal responses to dual-pulse SW application were similar to that observed in sham-SW treated animals; a small time-related fall in MAP of 6 to 10 mm Hg was seen with no significant alteration in GFR, ERPF or EPAH (Fig. 1). Likewise, renal filtration and perfusion, and tubular PAH transport were unaltered in the contralateral, untreated kidney of both groups (not shown).

Figure 1.

Blood pressure and renal responses in sham SWL-treated and SWL-treated kidneys. MAP, mean arterial pressure; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; ERPF, effective renal plasma flow; EPAH, renal extraction of PAH. * = P<0.05 from pre-treatment values.

Morphological measurements

Visual examination of the anterior and posterior surfaces of the kidneys revealed small focal sites of subcapsular bleeding in five of the eight Duet-treated kidneys, with the three remaining SW-treated kidneys being similar to sham SWL-treated kidneys in that they showed no evidence of subcapsular hemorrhage.

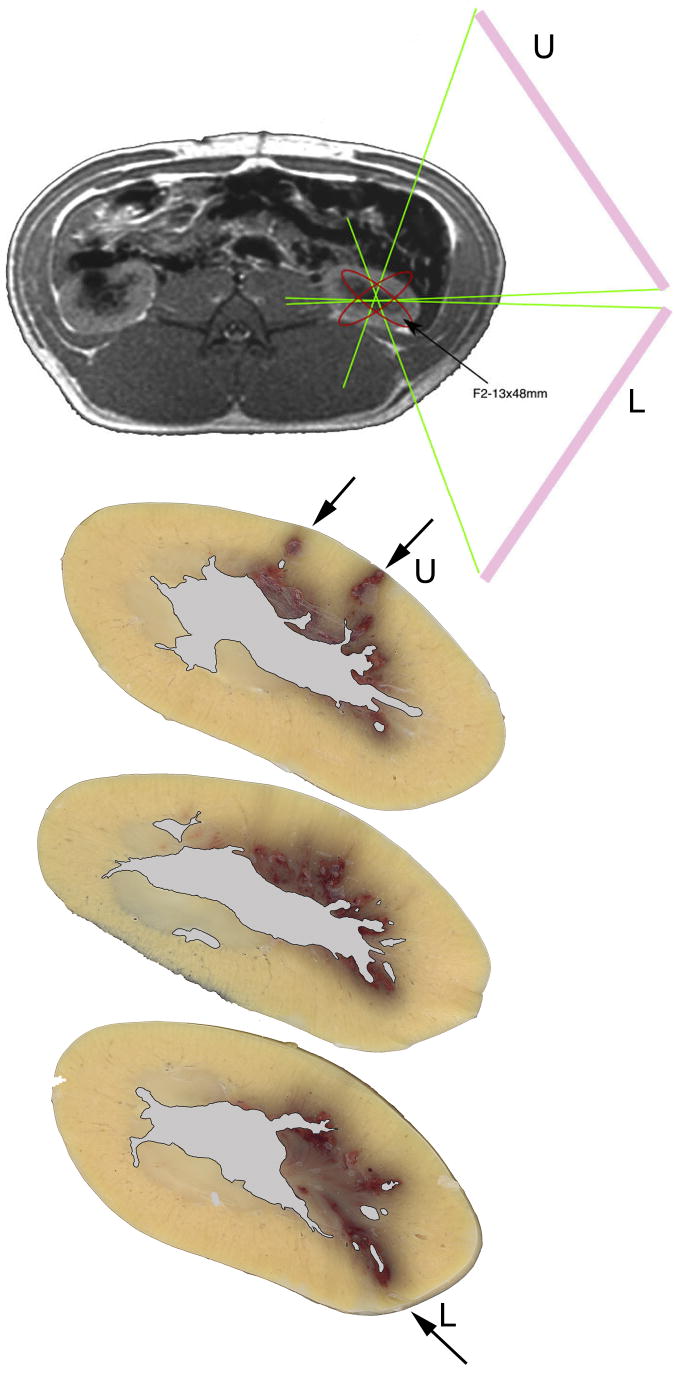

Hemorrhagic lesion sizes were quantified in six SW-treated kidneys. The degree of intraparenchymal hemorrhage induced by Duet lithotripsy measured 0.22 ± 0.09% FRV (P=0.0502): no detectable lesion in two kidneys, a focal papillary lesion in one kidney (< 0.1%), and small discrete lesions in papillae and cortex of three kidneys (0.37%, 0.40% and 0.46%). No tissue damage was observed in sham SWL-treated pigs. Figure 2 shows three consecutive unstained 5 mm cross sections of a Duet-treated kidney. Lesion sites (arrows) appear to correlate with the SW path from the upper (U) and lower (L) treatment heads when these cross sections were overlaid onto the MRI image of a pig and the superimposed location of the Duet’s dual treatment heads.

Figure 2.

MRI image of a pig with superimposed location of treatment heads and three serial unstained 5 mm cross sections of a Duet-treated kidney. The MRI image was taken at the level of both kidneys. Superimposed onto this MRI image is the location of the two treatment heads such that the focused SW is targeted onto the lower pole calyx of the left kidney. Lesion areas are colored reddish-brown and are clearly seen (arrows) in these cross sections obtained from a SW-treated kidney. Lesion sites appear to correlate with the SW path from the upper (U) and lower (L) treatment heads when these cross sections were overlaid onto the MRI image (with superimposed location of treatment heads) of a pig. The region of the renal sinus has been identified in these sections and given a grayish color. Cross sections are at a 2× magnification.

In vitro stone breakage studies

Stone breakage in alternating mode required 679 ± 24 SWs compared to 601 ± 35 SWs (~300 dual SWs) delivered in simultaneous mode. As the SW rate (120 SWs/min) for the two treatment heads was the same in both alternating and simultaneous modes, the overall treatment time was 170 seconds and 150 seconds, respectively. These results suggest a trend for total SW number and treatment time for stone comminution to be a little higher (~13%) in alternating mode versus simultaneous mode (p = 0.0666 each).

Discussion

An important motivation for conducting the current study was concern that delivering SWs to the kidney at the combined SW rate of 240 SWs/min (120 SWs/min/head) might enhance tissue damage. The results show otherwise. It has been shown in animal studies with single head lithotripters that treatment at very slow SW rate (30 SWs/min) produces little injury,14 and that treatment at extremely fast rate (900 SWs/min and faster) causes dramatically increased tissue damage.12,13 The lesion produced by 2400 SWs (1200 SWs/head, power level 10) at 120 SWs/min in alternating mode was quite low (0.22 ± 0.09% FRV) and compares favorably with the lesion (1.08 ± 0.38% FRV) produced by 2400 SWs delivered with the HM3 lithotripter at 120 SWs/min (24 kV).18

The injury observed in this study using SWs fired in alternating mode was statistically similar—even if somewhat lower—than in a previous study when SWs were delivered as simultaneous, dual pulses (0.22 ± 0.09% FRV versus 0.96 ± 0.39% FRV, P = 0.1044). 18 These results are difficult to compare directly as the conditions of treatment were different. Whereas, in alternating mode the SWs fired from the two treatment heads arrive at the focal point independently, the SWs fired in simultaneous mode intersect at the target. These coincident SWs produce a focal zone in which acoustic pressures are doubled. In addition, in simultaneous mode the location in the kidney of the combined focal zones is dependent on the timing of the two SWs such that this zone shifts in position throughout treatment. 18 Regardless of these differences it seems noteworthy that the injury observed in both modes was, indeed, quite low. One potential explanation is related to the efficiency of acoustic coupling in dry head lithotripters. In vitro studies have shown that air pockets at the coupling interface of a dry treatment head can dramatically reduce the transmission of SW energy. 20 Even under ideal conditions in vitro it is very difficult to attain coupling that is free of defects and having two treatment heads could only compound the difficulty in achieving good coupling. However, there is currently no means to determine the quality of coupling with any dry head device, thus there was no way to assess coupling in this work with the Duet. The coupling protocol that was used in these experiments with pigs followed the accepted clinical protocol for the Duet. Thus, as far as coupling is concerned the results may very well be consistent with what occurs in the treatment of patients.

A potentially important aspect of these studies of renal injury in pigs, those with the Duet and the work with the HM3, involves the sequence that was followed for the delivery of SWs. In particular it should be noted that treatment was not continuous and that there were periodic pauses built into the treatment protocol to check alignment and targeting. Recently we have observed that a brief pause in treatment can have a protective effect, acting to reduce the severity of renal injury. 21,22 For example, when pigs were treated with a priming dose of 100 SWs at 24 kV with the Dornier HM3 followed by a 3-minute break before the main dose of 2000 SWs was delivered, injury was significantly reduced compared to treatment with the main SW dose alone (0.51 ± 0.14% FRV versus 3.93 ± 1.29% FRV, P = 0.0135). 22 With regard to the current and previous studies with the Duet, as well as for the background data cited for the Dornier HM3, it is important to recognize that the values for renal injury pertain only to the specific treatment protocols that were followed. Because pauses in SW treatment could potentially evoke a protective response, one might predict a higher level of injury with the Duet and HM3 if treatment were continuous. Thus, it seems prudent to institute a brief (3–4 min) pause in SW delivery as part of the treatment protocol, regardless of the type of lithotripter being used.

A potential advantage of dual pulse lithotripsy compared to conventional SWL is the idea that SWs delivered from two sources may be able to break stones more efficiently than SWs from a single source. Others have presented in vitro data to suggest that this is the case.5 In the current study we limited our analysis of stone breakage to the two conditions most relevant to the efficacy and safety of treatment involving two shock sources. Our in vitro results demonstrate that number of delivered SWs and treatment times to achieve stone comminution were essentially similar under alternating or simultaneous SW firing modes of dual-head lithotripsy. With this in mind, a possible benefit of dual pulse lithotripsy in alternating mode is that renal function was not significantly changed after treatment. This is in contrast to the renal vasoconstriction normally observed following simultaneous delivery of dual-SWs,18 or SWs delivered from a conventional single-head lithotripter.16,18

In summary, treatment of the pig kidney with a clinical dose of SWs delivered in alternating (asynchronous) mode with the Direx Duet dual head lithotripter caused minimal alteration in renal function and produced only a small hemorrhagic lesion. This demonstrates that the delivery of SWs from two treatment heads is not inherently dangerous, and that firing two SW sources at a combined rate of 240 SWs/min does not cause significant morphological injury to the kidney.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the expert services of Cynthia D. Johnson and Philip M. Blomgren. We thank Dr. James C. Williams, Jr. for reviewing this manuscript and his helpful comments. This study was supported by funds from National Institute of Health Grant DK43881 and DK067133.

References

- 1.Bailey MR. Control of acoustic cavitation with application to lithotripsy. University of Texas; Austin: 1997. [Ph.D. dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sokolov DL, Bailey MR, Crum LA. Dual-pulse lithotripter accelerates stone fragmentation and reduces cell lysis in vitro. Ultrasound in Med & Biol. 2003;29:1045–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(03)00887-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheir KZ, El-Sheikh AM, Ghoneim MA. Synchronous twin-pulse technique to improve efficacy of SWL: Preliminary results of an experimental study. J Endourology. 2001;15:965–75. doi: 10.1089/089277901317203029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheir KZ, El-Diasty TA, Ismail AM. Evaluation of a synchronous twin-pulse technique for shock wave lithotripsy: the first prospective clinical study. BJU International. 2005;95:389–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenstein A, Sofer M, Matzkin H. Efficacy of the Duet lithotripter using two energy sources for stone fragmentation by shockwaves: an in vitro study. J Endourology. 2004;18:942–945. doi: 10.1089/end.2004.18.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janetschek G, Frauscher F, Knapp R, Hofle G, Peschel R, Bartsch G. New onset hypertension after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy: age related incidence and prediction by intrarenal resistive index. J Urol. 1997;158:346–351. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64475-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parks JH, Worcester E, Coe FC, Evan AP, Lingeman JE. Clinical implications of abundant calcium phosphate in routinely analyzed kidney stones. Kidney Int. 2004;66:777–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krambeck AE, Gettman MT, Rohlinger AL, Lohse CM, Patterson DE, Segura JW. Diabetes mellitus and hypertension associated with shock wave lithotripsy of renal and proximal ureteral stones at 19 years of followup. J Urol. 2006;175:1742–1747. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00989-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evan AP, Willis LR. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy: complications. In: Smith AD, Badlani GH, Bagley DH, Clayman RV, Docimo SG, Jordan GH, Kavoussi LR, Lee BR, Lingeman JE, Preminger GM, Segura JW, editors. Smith’s Textbook on Endourology. Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: BC Decker, Inc; 2007. pp. 353–365. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evan AP, McAteer JA. Q-effects of shock wave lithotripsy. In: Coe FL, Favus MJ, Pak CYC, Parks JH, Preminger GM, editors. Kidney Stones: Medical and Surgical Management. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 549–570. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evan AP, Willis LR, Lingeman JE, McAteer JA. Renal trauma and the risk of long-term complications in shock wave lithotripsy. Nephron. 1998;78:1–8. doi: 10.1159/000044874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delius M, Enders G, Xuan ZR, Liebich HG, Brendel W. Biological effects of shock waves: kidney haemorrhage by shock waves in dogs--administration rate dependence. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1988;14:689–694. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(88)90025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delius M, Mueller W, Goetz A, Liebich HG, Brendel W. Biological effects of shock waves: kidney hemorrhage in dogs at a fast shock wave administration rate of fifteen Hertz. J Lithotripsy Stone Dis. 1990;2:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evan AP, McAteer JA, Connors BA, Blomgren PM, Lingeman JE. Renal injury in SWL is significantly reduced by slowing the rate of shock wave delivery. BJUI. 2007;100:624–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evan AP, Willis LR, Connors B, Reed G, McAteer JA, Lingeman JE. Shock wave lithotripsy-induced renal injury. Am J Kidney Diseases. 1991;17:445–450. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80639-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willis LR, Evan AP, Connors BA, Shao Y, Blomgren PM, Pratt JH, Fineberg NS, Lingeman JE. Shockwave lithotripsy: dose-related effects on renal structure, hemodynamics, and tubular function. J Endourol. 2005;19:90–101. doi: 10.1089/end.2005.19.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blomgren PM, Connors BA, Lingeman JE, Willis LR, Evan AP. Quantitation of shock wave lithotripsy-induced lesion in small and large pig kidneys. Anat Rec. 1997;249:341–348. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199711)249:3<341::AID-AR4>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Handa RK, McAteer JA, Willis LR, Pishchalnikov YA, Connors BA, Ying J, Lingeman JE, Evan AP. Dual-head lithotripsy in synchronous mode: Acute effect on renal function and morphology in the pig. Brit J Urol Int. 2007;99:1134–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06736.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McAteer JA, Williams JC, Jr, Cleveland RO, Van Cauwelaert J, Bailey MR, Lifshitz DA, Evan AP. Ultracal-30 gypsum artificial stones for research on the mechanisms of stone breakage in shock wave lithotripsy. Urol Res. 2005;33:429–434. doi: 10.1007/s00240-005-0503-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pishchalnikov YA, Neucks JS, VonDerHaar RJ, Pishchalnikova IV, Williams JC, Jr, McAteer JA. Air pockets trapped during routine coupling in dry head lithotripsy can significantly decrease the delivery of shock wave energy. J Urol. 2006;176:2706–2710. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willis LR, Evan AP, Connors BA, Handa RK, Blomgren PM, Lingeman JE. Prevention of lithotripsy-induced renal injury by pretreating kidneys with low-energy shock waves. JASN. 2006;17:663–673. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005060634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connors BA, Evan AP, Blomgren PM, Handa RK, Willis LR, Gao S. Effect of initial shock wave voltage on shock wave lithotripsy-induced lesion size during step-wise voltage ramping. BJUI. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07922.x. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]