Summary

Curcumin, a compound found in the spice turmeric, has been shown to possess a number of beneficial biological activities exerted through a variety of different mechanisms. Some curcumin effects have been reported to involve activation of the nuclear transcription factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ), but the concept that curcumin might be a PPAR-γ ligand remains controversial. Results reported here demonstrate that, in contrast to the PPAR-γ ligands ciglitazone and rosiglitazone, curcumin is inactive in five different reporter or DNA-binding assays, does not displace [3H]rosiglitazone from the PPAR-γ ligand-binding site, and does not induce PPAR-γ–dependent differentiation of preadipocytes, while its ability to inhibit fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation is not affected by any of four PPAR-γ antagonists. These multiple lines of evidence conclusively demonstrate that curcumin is not a PPAR-γ ligand and indicate the need for further investigation of the mechanisms through which the compound acts.

Keywords: PPAR-γ, TGF-β, rosiglitazone, ciglitazone, PPRE, preadipocyte, fibroblast, turmeric, peroxisome, curcumin

Introduction

The polyphenol curcumin (diferuloylmethane; 1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-phenyl)1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione) is an orange-yellow compound with limited water solubility that is obtained from the turmeric plant, Curcuma longa. Curcumin has been shown to exhibit a variety of biological effects (Maheshwari et al., 2006) such as anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor and would-healing properties (Srivastava et al., 1995). These activities are exerted through an equally wide variety of signaling pathways, which may involve either inhibition (Chen and Tan, 1998; Gaedeke et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2007) or activation (Hu et al., 2005) of specific intracellular signaling pathways. These varied beneficial effects have led to investigation of curcumin as a potential therapeutic agent in a number of disease conditions (Aggarwal et al., 2007; Reddy et al., 2005; Thangapazham et al., 2006).

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) is a member of the nuclear receptor family of transcription factors, a large group of proteins that mediate ligand-dependent transcriptional activation and transrepression (Issemann and Green, 1990). PPAR-γ is highly expressed in adipose tissue and plays a crucial role in adipocyte differentiation (Lemberger et al., 1996). It is also expressed in a variety of other tissue and cell types, where it plays key roles in the regulation of metabolism and inflammation. Ligands for PPAR-γ include a variety of natural and synthetic compounds. Most of the natural ligands are fatty acids or fatty acid derivatives. Synthetic ligands include the thiazolidinediones, which are used as insulin sensitizing agents for treatment of type 2 diabetes (Berger and Moller, 2002).

Curcumin has been reported to activate PPAR-γ (Chen and Xu, 2005; Lin and Chen, 2008; Xu et al., 2003; Zheng and Chen, 2004). It remains unclear, however, whether this activation reflects curcumin binding to the receptor, as has been suggested (Chen and Xu, 2005; Jacob et al., 2007), or is entirely the result of indirect effects. The present study, utilizing multiple molecular and cellular assays, is the first to directly investigate the ability of curcumin to act as a PPAR-γ–activating ligand.

Materials and methods

Reagents

DMEM and DMEM/F12 were purchased from Gibco-BRL Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). High purity curcumin was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO), Bioprex (Pune, Maharashtra, India), and Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA); all experiments were repeated using each formulation. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from HyClone (Logan, UT). PPAR-γ antagonists GW9662 and BADGE were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI), while PPAR-γ Antagonist III (G3335), and T0070907 were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). The PPAR-γ agonists ciglitazone and rosiglitazone were purchased from Cayman. Aliquots of agonists and antagonists were dissolved in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 100 mM and stored at −30 °C until use. [3H]rosiglitazone was obtained from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). Anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mouse monoclonal antibody was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK), while anti–α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) mouse antibody, clone 1A4, was obtained from Dako Automation (Carpentaria, CA), and TGF-β1 was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). GAL4-PPAR-γ plasmid was a kind gift from YE Chen, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. The aP2-luc plasmid (Camp et al., 2001) and the FATP-PPRE-luc plasmid (Monajemi et al., 2007) were constructed as previously described.

Cell culture and transfection

CV-1 and 3T3-L1 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). IMR-90 cells were obtained from the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, NJ). CV-1 cells were grown to 70% confluence in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. Cells were then transiently co-transfected with pRL-SV40 and a PPAR-dependent luciferase reporter, pFATPluc. In separate experiments, cells were co-transfected with pRL-SV40 plus a luciferase gene under the control of four Gal4 DNA-binding elements (UASG × 4 TK-luciferase) and a plasmid containing the ligand-binding domain for PPAR-γ fused to the Gal4 DNA-binding domain. All transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty-four h after transfection, cells were treated with test compounds and incubated for an additional 24 h in medium with 10% FBS. The resulting luciferase activity was measured with reporter luciferase assay kits (Promega; Madison, WI) employing a Modulus 9201 luminometer (Turner Biosystems; Sunnydale, CA) and normalized by comparison to Renilla luciferase.

Nuclear protein preparation and PPAR-γ–DNA binding assay

CV-1 and IMR-90 cells were plated in 100 mm dishes at 70% confluence. The cells were treated with curcumin or rosiglitazone for 3 h, after which nuclear protein was isolated (Cayman nuclear protein extraction kit). Protein concentrations were estimated using the Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) DC protein assay. PPAR-γ DNA-binding activity in the nuclear protein was detected by an ELISA-based PPAR-γ transcription factor assay (Cayman) that detects PPAR-γ bound to PPRE-containing double-stranded DNA sequences.

Ligand binding by PPAR-γ–GST

The ligand binding domain of PPAR-γ was introduced into the pGEX-2T bacterial expression vector (Amersham Pharmacia; Buckinghamshire, UK). Expression of glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-tagged PPAR-γ in Escherichia coli strain BL21-DE3 (Novagen; San Diego, CA) was induced by the addition of 1 mM isopropyl-1-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG) to the growth medium. Bacterial extracts were prepared using standard methods and the fusion proteins were purified using Glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare; Piscataway, NJ). GST–PPAR-γ protein induction and receptor binding was assessed as described (Fu et al., 2003). Briefly, 5 μg of GST–PPAR-γ protein, [3H]rosiglitazone (specific activity, 5 Ci/mmol), and various concentrations of curcumin or unlabeled rosiglitazone were incubated for 2 h at 25 °C in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM KCl, and 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Bound [3H]rosiglitazone was separated from free [3H]rosiglitazone by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 1 min. The radioactivity of the bound [3H]rosiglitazone fraction was determined by liquid scintillation counting.

3T3-L1 differentiation and Oil Red O staining

3T3-L1 preadipocytes were grown and maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS. Differentiation of preadipocytes was studied in cells 2 days following confluence (designated day 0). These cells were cultured for 14 d in DMEM containing 10% FBS and either curcumin or rosiglitazone. The medium was changed every 2 d. The differentiated adipocytes were stained by Oil Red O (Sigma) as described previously (Song et al., 2007). Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h, followed by rinsing with PBS and with water. After the rinsing, cells were stained with 0.1% Oil Red O for 1 h. Plates were rinsed with water and images of cells on the plate were taken in water.

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRI-Reagent (Sigma) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was generated from 1 μg of total RNA and real-time quantitative PCR was performed using Sybr Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative changes were expressed relative to β-actin. Primers used were:

PPAR-γ: (F) 5′-ATTCTGGCCCACCAACTTCGG-3′

(R) 5′-TGGAAGCCTGATGCTTTATCCCCA-3′

β-actin: (F) 5′-GTGGGGCGCCCCCAGGCACCA-3′

(R) 5′-GCTCGGCCGTGGTGGTGAAGC-3′

Western immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation buffer and whole-cell protein was quantified. Ten μg of protein was subjected to 12% Tris-glycine SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen). After transfer to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore), α-SMA and GAPDH were detected using appropriate dilutions of primary mouse monoclonal antibodies followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Protein was visualized using the ECL chemiluminescent detection system (Amersham Pharmacia).

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as mean ± SE and were analyzed with the Prism 5.0 statistical program (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Comparisons between experimental groups were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. All data shown are averages from at least 3 independent experiments. Differences were considered significant if P was less than .05.

Results

Curcumin does not activate PPAR reporter constructs

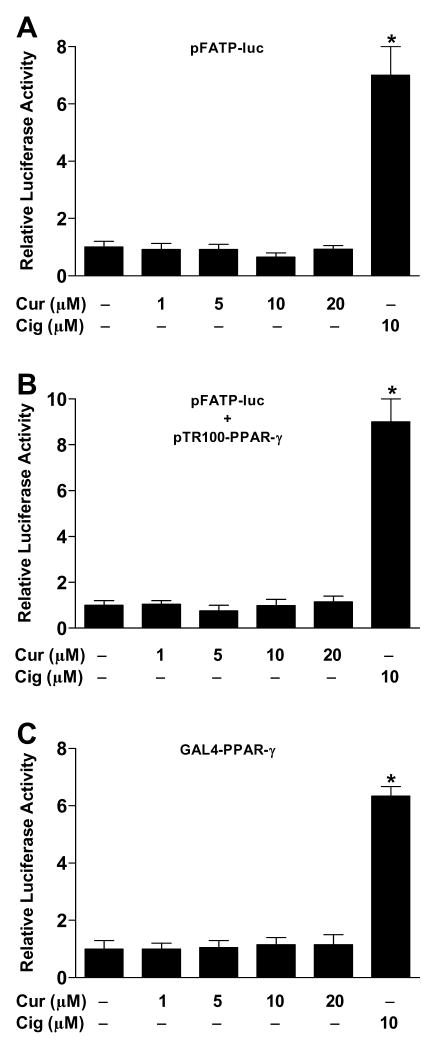

Previous studies have reported that curcumin activates PPAR-γ. To test this, we transfected CV-1 cells with FATP-PPRE-luc plasmid, in which the peroxisome proliferator response element (PPRE) from fatty acid transport protein controls expression of firefly luciferase. After 24 h, cells were treated with curcumin at different concentrations (1–20 μM) and following an additional 24-h incubation, cells were lysed and luciferase activity was measured. Curcumin did not increase the relative transcriptional activity of PPAR-γ in CV-1 cells at any dose tested (Figure 1A). By contrast, the positive control ciglitazone (10 μM) increased transcriptional activity ~7-fold.

Figure 1.

Curcumin is inactive in reporter assays. CV-1 cells were transiently transfected with pRL-SV40 and with one of the following constructs: (A) PPAR-dependent luciferase reporter, pFATP-luc; (B) PPAR-γ expression plasmid, pTR100-PPAR-γ, along with pFATP-luc; (C) PPAR-γ GAL4 reporter system, UASG × 4 TK-luciferase + GAL4-PPAR-γ. Cells were then incubated with vehicle (DMSO), curcumin (Cur; 1–20 μM) or ciglitazone (Cig; 10 μM). After 24 h, the relative luciferase activity was calculated by normalizing firefly luciferase activity to that of Renilla luciferase. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

To increase the robustness of the reporter assay, CV-1 cells were co-transfected with a PPAR-γ expression plasmid (TR100-PPAR-γ) in addition to FATP-PPRE-luc. Curcumin (1–20 μM) did not induce detectable PPAR-γ activation even in the presence of elevated amounts of receptor, while transcriptional activity induced by ciglitazone (10 μM) was greater than that observed in the absence of the expression plasmid (Figure 1B). Similar results were obtained with curcumin and rosiglitazone in NIH/3T3 cells with an aP2-PPRE-luc reporter plasmid in the presence of TR100-PPAR-γ (data not shown).

We also performed reporter assays using the highly specific Gal4-luc system, in which the PPAR-γ ligand-binding domain is fused to the Gal4 DNA-binding domain and a luciferase reporter gene is under the control of four Gal4 DNA-binding elements. In this case also, we did not see activation of PPAR-γ by curcumin (Figure 1C).

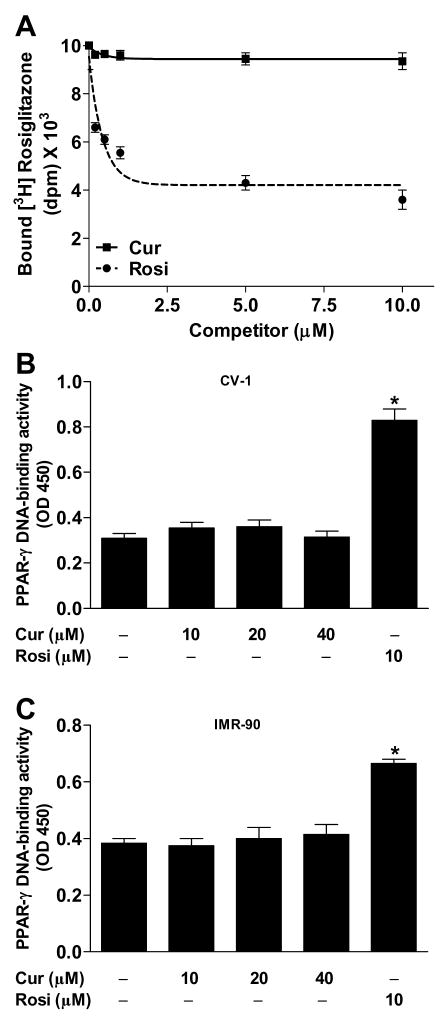

Curcumin does not bind to the ligand-binding domain of PPAR-γ or stimulate binding of PPAR-γ to DNA

To directly determine whether curcumin binds to the PPAR-γ activating site, we quantified displacement of bound [3H]rosiglitazone by unlabeled rosiglitazone or curcumin. The Ki for rosiglitazone was found to be ~50 nM, consistent with reported values (Schopfer et al., 2005). By contrast, curcumin displayed no competition for the binding site at concentrations up to 10 μM (Figure 2A) or even as high as 40 μM (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Curcumin does not bind to or activate PPAR-γ. (A) Competitive binding assay was performed using GST-PPAR-γ ligand-binding domain and [3H]rosiglitazone in the presence of unlabeled curcumin (Cur) or rosiglitazone (Rosi). In a separate experiment, PPAR-γ activation was analyzed by DNA-binding assay in (B) CV-1 and (C) IMR-90 cells. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

We then examined the ability of curcumin to stimulate binding of PPAR-γ to DNA, using a commercially available transcription factor assay that measures binding of PPAR-γ to double stranded DNA probe containing a PPRE sequence. Cells were treated with curcumin (10–40 μM), rosiglitazone (10 μM), or vehicle (DMSO) for 3 h, after which nuclear extracts were prepared and subjected to PPAR-γ binding assay. In order to investigate the possibility that curcumin upregulates PPAR-γ expression, we employed IMR-90 as well as CV-1 cells. Curcumin gave results similar to those with vehicle, demonstrating no activation of PPAR-γ in either CV-1 cells (Figure 2B) or IMR-90 cells (Figure 2C). Rosiglitazone (10 μM), as expected, increased PPAR-γ binding.

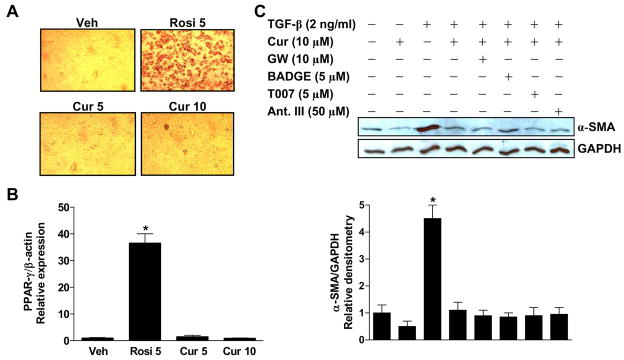

Curcumin does not induce differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes

To investigate PPAR-γ–mediated biological effects of curcumin, we employed a well established model of adipocyte differentiation. PPAR-γ plays an essential role in the differentiation of adipocytes (Tontonoz et al., 1994), with selective disruption of PPAR-γ resulting in impaired development of adipose tissue (Evans et al., 2004). 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were treated with curcumin (5 and 10 μM) or rosiglitazone (5 μM) for 2 weeks. Adipocyte differentiation was assessed both morphologically and by means of Oil Red O staining, which reveals the accumulation of intracellular lipids (Figure 3A). Expression of PPAR-γ, which is upregulated during differentiation, was also assessed (Figure 3B). On both assessments, vehicle and curcumin did not induce differentiation while rosiglitazone treatment produced the expected PPAR-γ–dependent differentiation.

Figure 3.

Curcumin has no effect on preadipocyte differentiation and effects on fibroblast differentiation are not blocked by PPAR-γ antagonists. (A, B) 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were treated with curcumin (Cur; 5 and 10 μM) or rosiglitazone (Rosi; 5 μM) for 2 weeks. Adipocyte differentiation was assessed (A) both morphologically and via oil red O staining and (B) by relative expression of PPAR-γ mRNA. The MDI differentiation protocol (isobutylmethylxanthine + dexamethasone for 48 h, followed, after their removal, by insulin + the test compound) was used in all experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle. (C) Confluent, serum-deprived human fetal lung fibroblasts (IMR-90) were pretreated with PPAR-γ antagonists (GW: GW9662, T007: T0070907, and Ant. III: Antagonist III) for 1 h, then with curcumin for 1 h, after which cells were stimulated with TGF-β (2 ng/ml). After an additional 24 h, cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Membranes were probed first with anti–α-SMA antibody, then reprobed with anti-GAPDH antibody to confirm equal protein loading. The blots were scanned densitometrically. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

PPAR-γ antagonists do not block curcumin inhibition of TGF-β–induced fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation

As a further test of the extent to which biological effects of curcumin may be mediated by PPAR-γ activation, we examined inhibition of the TGF-β–induced differentiation of human lung fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. PPAR-γ activation has been shown to inhibit this differentiation, signaled by appearance of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Burgess et al., 2005; Milam et al., 2008). We treated serum-starved IMR-90 fibroblasts with curcumin (10 μM) for 1 h followed by TGF-β (2 ng/ml), finding that curcumin inhibited the expression of α-SMA. To determine whether this inhibition is mediated through PPAR-γ, we added one of four different PPAR-γ antagonists 1 h prior to curcumin. α-SMA expression was assessed by Western immunoblotting and quantified by densitometric scanning of the blots (Figure 3C). None of the antagonists reduced the ability of curcumin to inhibit myofibroblast differentiation.

Discussion

Previous studies have suggested that certain curcumin effects involved an increase in PPAR-γ activity. Some investigators have suggested that this increased activity may represent direct ligand-binding activation of the receptor by curcumin, although this remains controversial. Our results conclusively address this issue utilizing a variety of rigorous assays.

At the molecular level, ligand-induced activation of PPAR-γ is reflected in increased binding to its response elements. We find, however, that incubation with curcumin does not increase binding to the consensus PPRE in a transcription factor assay, nor does it increase transcriptional activity in any of four different reporter assays. Furthermore, definitively, curcumin does not displace a standard synthetic PPAR-γ ligand from the receptor’s binding site. At the cellular level, we investigated the ability of curcumin to induce PPAR-γ–mediated differentiation of preadipocytes to adipocytes. Whereas synthetic PPAR-γ ligands induced differentiation, as expected, curcumin did not. Furthermore, although curcumin reduces the ability of TGF-β to induce fibroblast differentiation, as do PPAR-γ ligands, a variety of different PPAR-γ antagonists have no effect of curcumin’s inhibitor activity. Thus, at both the molecular and cellular levels, our results support the conclusion that the known biological activities of curcumin do not involve binding to, and activation of, the nuclear transcription factor PPAR-γ.

Studies in hepatic stellate cells (Lin and Chen, 2008; Xu et al., 2003; Zheng and Chen, 2004), in a rodent model of sepsis (Siddiqui et al., 2006), and in Moser colon cancer cells (Chen and Xu, 2005) have suggested that PPAR-γ signaling is required for curcumin to exert the effects observed. In Moser cells, it was found that curcumin reduced phosphorylation and consequent inactivation of PPAR-γ (Chen and Xu, 2005). Upregulation of PPAR-γ expression has been demonstrated in hepatic stellate cells (Cheng et al., 2007; Lin and Chen, 2008; Xu et al., 2003; Zheng and Chen, 2004; Zhou et al., 2007), in a macrophage cell line (Siddiqui et al., 2006), and in colonic mucosal cells from a rodent model of colitis induced by trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (Zhang et al., 2006). One study found that this upregulation of PPAR-γ expression was secondary to inhibition of PDGF and EGF signaling pathways (Zhou et al., 2007). Furthermore, in the rat model of colitis induced by trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid, curcumin was observed to increase levels of the endogenous PPAR-γ ligand 15d-PGJ2 (Zhang et al., 2006). None of these studies directly examined possible binding of curcumin to the PPAR-γ ligand-binding site, however. Although the reported increases in amount of receptor, and possibly of its endogenous ligands, appear to be plausible explanations for the results obtained, the possibility that curcumin also bound to and directly activated PPAR-γ had been suggested (Chen and Xu, 2005; Jacob et al., 2007).

In direct contrast to our results, one group has specifically asserted that curcumin is a PPAR-γ ligand (Kuroda et al., 2005; Nishiyama et al., 2005). This group reported increased activity in a GAL4-PPAR-γ chimeric assay in CV-1 cells. These researchers also noted that curcumin induced differentiation of preadipocytes, which we did not observe, although these were primary human preadipocytes rather than the standard 3T3-L1 cells that were employed in this study. Furthermore, while we repeated all experiments with three different commercially available high-purity curcumin formulations (data not shown), this group conducted preadipocyte differentiation studies and some ligand-binding studies with ethanolic extracts of turmeric. Other ligand-binding studies were done with curcumin purified in their laboratories. Because these curcumin preparations were not standardized, the possible role of other compounds present in these formulations cannot be ruled out. Recently, it has also been shown that curcumin downregulates PPAR-γ expression in preadipocytes, thus actively inhibiting their differentiation (Lee et al., 2009). This observation further supports our conclusions.

In summary, our results conclusively show that curcumin is not a PPAR-γ ligand. Thus, any observed PPAR-γ–mediated effects of curcumin must be indirect and mediated through effects of receptor expression or levels of endogenous ligands that are mediated through other pathways. Since we have now ruled out one suggested mechanism for curcumin, further study of alternative mechanisms is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL070068 and AI079539, a University of Michigan Global REACH International Grant and the Martin E. Galvin Fund and Quest for Breath Foundation (all to R.C.R.).

References

- Aggarwal BB, Sundaram C, Malani N, Ichikawa H. Curcumin: the Indian solid gold. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;595:1–75. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger J, Moller DE. The mechanisms of action of PPARs. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:409–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess HA, Daugherty LE, Thatcher TH, Lakatos HF, Ray DM, Redonnet M, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. PPARgamma agonists inhibit TGF-beta induced pulmonary myofibroblast differentiation and collagen production: implications for therapy of lung fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L1146–1153. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00383.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp HS, Chaudhry A, Leff T. A novel potent antagonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma blocks adipocyte differentiation but does not revert the phenotype of terminally differentiated adipocytes. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3207–3213. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Xu J. Activation of PPAR γ by curcumin inhibits Moser cell growth and mediates suppression of gene expression of cyclin D1 and EGFR. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G447–456. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00209.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-R, Tan T-H. Inhibition of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathway by curcumin. Oncogene. 1998;17:173–178. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Ping J, Xu LM. Effects of curcumin on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ expression and nuclear translocation/redistribution in culture-activated rat hepatic stellate cells. Chin Med J (Engl) 2007;120:794–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RM, Barish GD, Wang YX. PPARs and the complex journey to obesity. Nat Med. 2004;10:355–361. doi: 10.1038/nm1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Gaetani S, Oveisi F, Lo Verme J, Serrano A, Rodriguez De Fonseca F, Rosengarth A, Luecke H, Di Giacomo B, Tarzia G, Piomelli D. Oleylethanolamide regulates feeding and body weight through activation of the nuclear receptor PPAR-alpha. Nature. 2003;425:90–93. doi: 10.1038/nature01921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaedeke J, Noble NA, Border WA. Curcumin blocks multiple sites of the TGF-β signaling cascade in renal cells. Kidney Int. 2004;66:112–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Du Q, Vancurova I, Lin X, Miller EJ, Simms HH, Wang P. Proapoptotic effect of curcumin on human neutrophils: activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2571–2578. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000186760.20502.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issemann I, Green S. Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proliferators. Nature. 1990;347:645–650. doi: 10.1038/347645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob A, Wu R, Zhou M, Wang P. Mechanism of the Anti-inflammatory Effect of Curcumin: PPAR-gamma Activation. PPAR Res. 2007;2007:89369. doi: 10.1155/2007/89369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda M, Mimaki Y, Nishiyama T, Mae T, Kishida H, Tsukagawa M, Takahashi K, Kawada T, Nakagawa K, Kitahara M. Hypoglycemic effects of turmeric (Curcuma longa L. rhizomes) on genetically diabetic KK-Ay mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:937–939. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YK, Lee WS, Hwang JT, Kwon DY, Surh YJ, Park OJ. Curcumin exerts antidifferentiation effect through AMPKalpha-PPAR-gamma in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and antiproliferatory effect through AMPKalpha-COX-2 in cancer cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:305–310. doi: 10.1021/jf802737z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemberger T, Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: a nuclear receptor signaling pathway in lipid physiology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:335–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Chen A. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ by curcumin blocks the signaling pathways for PDGF and EGF in hepatic stellate cells. Lab Invest. 2008;88:529–540. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari RK, Singh AK, Gaddipati J, Srimal RC. Multiple biological activities of curcumin: a short review. Life Sci. 2006;78:2081–2087. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milam JE, Keshamouni VG, Phan SH, Hu B, Gangireddy SR, Hogaboam CM, Standiford TJ, Thannickal VJ, Reddy RC. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit profibrotic phenotypes in human lung fibroblasts and bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L891–901. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00333.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monajemi H, Zhang L, Li G, Jeninga EH, Cao H, Maas M, Brouwer CB, Kalkhoven E, Stroes E, Hegele RA, Leff T. Familial partial lipodystrophy phenotype resulting from a single-base mutation in deoxyribonucleic acid-binding domain of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1606–1612. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama T, Mae T, Kishida H, Tsukagawa M, Mimaki Y, Kuroda M, Sashida Y, Takahashi K, Kawada T, Nakagawa K, Kitahara M. Curcuminoids and sesquiterpenoids in turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) suppress an increase in blood glucose level in type 2 diabetic KK-Ay mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:959–963. doi: 10.1021/jf0483873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy RC, Vatsala PG, Keshamouni VG, Padmanaban G, Rangarajan PN. Curcumin for malaria therapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;326:472–474. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopfer FJ, Lin Y, Baker PRS, Cui T, Garcia-Barrio M, Zhang J, Chen K, Chen YE, Freeman BA. Nitrolinoleic acid: an endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2340–2345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408384102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui AM, Cui X, Wu R, Dong W, Zhou M, Hu M, Simms HH, Wang P. The anti-inflammatory effect of curcumin in an experimental model of sepsis is mediated by up-regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1874–1882. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000221921.71300.BF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song DH, Getty-Kaushik L, Tseng E, Simon J, Corkey BE, Wolfe MM. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide enhances adipocyte development and glucose uptake in part through Akt activation. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1796–1805. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava KC, Bordia A, Verma SK. Curcumin, a major component of food spice turmeric (Curcuma longa) inhibits aggregation and alters eicosanoid metabolism in human blood platelets. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1995;52:223–227. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(95)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangapazham RL, Sharma A, Maheshwari RK. Multiple molecular targets in cancer chemoprevention by curcumin. AAPS J. 2006;8:E443–449. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPAR gamma 2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell. 1994;79:1147–1156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Fu Y, Chen A. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptorγ contributes to the inhibitory effects of curcumin on rat hepatic stellate cell growth. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G20–30. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00474.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Deng C, Zheng J, Xia J, Sheng D. Curcumin inhibits trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid-induced colitis in rats by activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1233–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S, Chen A. Activation of PPAR γ is required for curcumin to induce apoptosis and to inhibit the expression of extracellular matrix genes in hepatic stellate cells in vitro. Biochem J. 2004;384:149–157. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Zheng S, Lin J, Zhang QJ, Chen A. The interruption of the PDGF and EGF signaling pathways by curcumin stimulates gene expression of PPAR γ in rat activated hepatic stellate cell in vitro. Lab Invest. 2007;87:488–498. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]