Abstract

Palmitoylation, a post-translational modification of cysteine residues with the lipid palmitate, has recently emerged as an important mechanism for regulating protein trafficking and function. With the identification of 23 DHHC mammalian palmitoyl acyl transferases (PATs), a key question was the nature of substrate-enzyme specificity for these PATs. Using the acyl-biotin exchange palmitoylation assay, we compared the substrate specificity of four neuronal PATs, namely DHHC-3, DHHC-8, HIP14L (DHHC-13), and HIP14 (DHHC-17). Exogenous expression of enzymes and substrates in COS cells reveals that HIP14L and HIP14 modulate huntingtin palmitoylation, DHHC-8 modulates paralemmin-1 palmitoylation, and DHHC-3 shows the least substrate specificity. These in vitro data were validated by lentiviral siRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous HIP14 and DHHC-3 in cultured rat cortical neurons. PATs require the presence of palmitoylated cysteines in order to interact with their substrates. To understand the elements that influence enzyme/substrate specificity further, we fused the HIP14 ankryin repeat domain to the N terminus of DHHC-3, which is not a PAT for huntingtin. This modification enabled DHHC-3 to behave similarly to HIP14 by modulating palmitoylation and trafficking of huntingtin. Taken together, this study indicates that individual PATs have specific substrate preference, determined by regulatory domains outside the DHHC domain of the enzymes.—Huang, K., Sanders, S., Singaraja, R., Orban, P., Cijsouw, T., Arstikaitis, P., Yanai, A., Hayden, M. R., El-Husseini, A. Neuronal palmitoyl acyl transferases exhibit distinct substrate specificity.

Keywords: acyl-biotin exchange, DHHC proteins, HIP14, HIP14L, huntingtin, SNAP25

Protein palmitoylation represents a common post-translational lipid modification of many proteins that involves the addition of palmitate, a 16-carbon saturated fatty acid, to specific cysteine residues via a thioester linkage. At least 32 neuronal proteins have been shown to be palmitoylated (1). These include channels, cell adhesion molecules, scaffolding molecules, neurotransmitter release machinery, signaling proteins (2,3,4,5), and huntingtin (6, 7), a protein that, when mutated, causes Huntington disease (HD) (8). Notably, palmitoylation is reversible, which allows it to dynamically regulate protein function and participate in diverse aspects of neuronal signaling (reviewed in refs. 1, 4). For example, glutamate receptor activity regulates palmitoylation of PSD95, and the regulated addition and removal of palmitate on this postsynaptic scaffolding protein in turn regulates the synaptic retention and removal of glutamate receptors (9). This process is thought to be fundamental for synaptic plasticity, the dynamic changes in the content and morphology of synapses associated with learning and memory.

The identity of the protein fatty acyltransferases (PATs) that enzymatically modify palmitoylated proteins has recently been discovered (6, 10,11,12,13). The defining feature of this family of PATs is the presence of a cysteine-rich domain (CRD) with a core Asp-His-His-Cys (DHHC) motif that is essential for PAT activity in vitro and in vivo (6, 11, 13). DHHC-CRD containing proteins are conserved from yeast to mammals. Genetic and biochemical studies have identified substrates for several DHHC proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (10, 13), and proteomic analyses have significantly expanded the repertoire of substrates for this family of enzymes (3). Mammals contain 23 DHHC proteins (11), and their tissue distribution and subcellular localization has recently been documented (14). When expressed in HEK cells, the majority of these DHHC proteins localize to the ER, Golgi, and endosomal vesicles, whereas some localize to the plasma membrane (14). However, whether the localization of an enzyme directly correlates with its potential substrate is not yet known. Another unanswered question is whether different PATs exhibit distinct substrate specificity and what factors may influence this selectivity. In this study, four brain-enriched DHHC-containing enzymes, namely DHHC-3, DHHC-8, HIP14L (DHHC-13), and HIP14 (DHHC-17), were used to address these questions.

The method most commonly used to quantify protein palmitoylation involves metabolic labeling of cultured cells with radiolabeled palmitate ([3H]-palmitate or [125I]-palmitate) for 3–5 h before harvesting cells and immunoprecipitating the proteins of interest (protocol reviewed in ref. 15). This approach is limited to use in cultured live cells and requires incubation with expensive radiolabeled palmitate that will only label the fraction of the available protein that is turned over during the labeling. A novel approach developed by Drisdel and Green (16, 17) overcomes these limitations by allowing detection of the total pool of palmitoylated proteins present in tissue extracts. This approach is known as acyl-biotin exchange (ABE) labeling and involves blockade of free thiols with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), cleavage of the Cys-palmitoyl thioester linkage with hydroxylamine, and labeling of newly exposed thiols with a sulfhydryl-specific labeling compound, such as nonradioactive biotin-BMCC (1-biotinamido-4-[4′-(maleididomethyl) cyclohexanecarboxamido] butane) (16, 17). The palmitoylated protein can then be detected by Western blotting using strepdavidin or anti-biotin antibodies. This approach is highly sensitive and allows the use of a variety of probes, radiolabeled ([3H]-NEM) or nonradioactive (biotin-BMCC), and facilitates quantitative estimates of the total palmitoylated pool of a specific protein. It also allows for the rapid assessment of changes in the dynamics of protein palmitoylation after stimulation of specific signaling pathways or on alterations in neuronal activity (18).

Using this approach, we contrasted the enzymatic activity of four neuronal PATs (DHHC enzymes) both by exogenous expression and knockdown of endogenous enzymes. We then examined the interactions between substrates and their cognate PATs. Finally, we determined the structural elements that influence the specificity of the enzymes for their substrates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction

The following cDNAs were used for COS cell transfection: DHHC-3 (Flag tagged and GFP tagged) (kindly provided by Dr. Bernhard Lüscher, Penn State University, State College, PA, USA), DHHC-8 in pEF-Bos-HA (kindly provided by Dr. Masaki Fukata, National Institute for Physiological Sciences, Okazaki, Japan, and Dr. David Bredt, Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA), GluR1 GFP and GluR2 GFP in pRK5 (kindly provided by Dr. Takashi Hayashi and Dr. Richard L. Huganir, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA), DHHC-13 Flag and HIP14 Flag in pCIneo vector, HIP14ΔDHHC (Flag tagged and GFP tagged) lacking aa 440–487 in pCIneo vector, HIP14ΔANK-GFP lacking aa 89–257 in pCIneo vector, SNAP25 in pEGFP-C1 vector, PSD95-GFP in pGW1 vector, PSD95 Flag in pcDNA3 vector, huntingtin 1–548 aa in pCIneo vector, and paralemmin in pEGFP-C1 vector. ANK-DHHC3 was generated by the following two-step cloning: first, DHHC-3 cDNA was subcloned into the HindIII and EcoR I sites of pEGFP N3; then, amino acid fragment 1–294 of HIP14 was further subcloned into the BglII and HindIII sites of the previous construct.

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used for immunofluorescence (IF) and immunoblotting (IB): HIP14 (rabbit, 1:200 for IF and IB; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA); HIP14 (rabbit, 1:200 for IB; made in-house); DHHC-3 (also named GODZ; rabbit, 1:200 for IF; Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA); huntingtin 2166 (mouse, 1:1000 for IF and IB; Chemicon); HA (mouse, 1:1000 for IF and IB; BAbCO, Richmond, CA, USA); Flag M2 (mouse, 1:1000 for IF and IB; Sigma); GFP (rabbit, 1:1000; made in-house); GFP (rabbit, 1:2000 for IF and IB; Synaptic Systems, Goettingen, Germany); GM130 (mouse, 1:200 for IF; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA); Calnexin (rabbit, 1:500 for IF; Sigma); EEA1 (mouse, 1:200 for IF; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); GluR1 and GluR2 (rabbit serum, 1:1000 for IB; gift from Dr. Yutian Wang, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada); PSD-95 (rabbit, 1:1000 for IF; made in-house); PSD-95 (mouse, 1:1000 for IB; ABR, Golden, CO, USA); and GAD65 (rabbit, 1:1000 for IB) and synaptophysin (mouse, 1:1000 for IF) (both Abcam). Fluorescently conjugated secondary antibodies for immunocytochemistry were used as described previously (19). Fluorescently conjugated secondary antibodies for immunoblotting were IRDye 800 antibody (mouse, 1:10,000; Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA, USA) and Alexa Fluor 680 antibody (rabbit, 1:10,000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Cell culture and transfections

All reagents for cell cultures were purchased from Invitrogen. COS cells were cultured as described previously (6). COS cells were transiently transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as described by the manufacturer. At 24 to 48 h post-transfection, cells were processed as described for each experiment.

Immunocytochemistry and imaging

Coverslips were removed from culture wells and fixed in 2% PFA. The cells were washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.3% Triton-X-100 (PBS-T) before incubation with each antibody. All antibody incubations were performed in blocking solution (2% normal goat or horse serum in PBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. The coverslips were then mounted on slides (Frost Plus; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) with Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL, USA). Images were acquired using either a Zeiss Axiovert M200 motorized microscope by using a monochrome 14-bit Axiocam HR charge-coupled device camera at 1300 × 1030 pixels (Zeiss Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). For confocal microscopy, images were captured using the Zeiss Confocal LSM510 Meta system ×63 objective (NA=1.2) water lens as described previously (20). Images were captured using a 512 × 512 pixel screen, and gain settings were 500–700. Scan speed function was set to 6, and the mean of 8 lines was detected. Zoom function was set to 1, and the pinhole was set to 1 airy unit. Z-series were used to capture out-of-focus dendrites, and sections were taken at a depth interval of 0.500 μm.

For lentiviral siRNA infection experiment, images were first captured using an ×20 objective to measure the efficiency of lentiviral infection. To quantify the knockdown effect of HIP14 siRNA and DHHC-3 siRNA, images were captured using 63× objective oil lens at a fixed exposure. Because HIP14 and DHHC-3 are predominantly localized to the Golgi compartment in the soma, somatic immunofluorescent intensity of HIP14 or DHHC-3 in both control siRNA and target siRNA infected neurons were measured and normalized to the area of the soma by Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

COS-7 cells were lysed in ice-cold buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl; 1% triton; 1 mg/ml protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA), and 0.25 mg/ml PMSF. Cell lysates were rotated at 4°C for 30 min before the insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 15 min. Lysates were precleared by incubation with protein A+G agarose (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) for 45 min at 4°C with rocking. Precleared samples were then immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP (3 μg, rabbit, homemade) antibody. Proteins in both the cell lysates and immunoprecipitates were heated in SDS sample buffer before separation by SDS-PAGE. After overnight transfer of the proteins onto nitrocellulose membranes, Western blots were performed using the antibodies described above (see Antibodies).

Btn-BMCC labeling

Following immunoprecipitation, beads were incubated with wash buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4; 5 mM EDTA; 150 mM NaCl; containing 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with 50 mM NEM for 1 h at 4°C, followed by treatment with 1 M hydroxylamine (pH 7.4) for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the beads were incubated with 0.5 μM biotin-BMCC (pH 6.2) at 4°C for 1 h to label reactive cysteine residues. Following SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF membranes, the blots were reacted with strepdavidin-HRP to detect biotin-BMCC-labeled proteins.

Lentiviral construction and virus production

The sequences of scramble, HIP14, and DHHC-3 shRNA were described previously (6, 7). The complete shRNA expression cassettes (the H1 promoter plus the siRNA template) were excised from the corresponding recombinant pSUPER plasmids (OligoEngine, Seattle, WA, USA) by XbaI and XhoI and ligated into pLentiLox3.7 (pLL3.7) vector. This vector also expresses EGFP as a reporter gene under the control of the neuron-specific synapsin promoter. Plasmids were purified by using the EndoFree Plasmid Maxikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), and all constructs were verified by sequencing before use. The HIP14 siRNA target sequence was GGAGATACAAGCACTTTAA, the DHHC-3 siRNA target sequence was CCACTAAAGAGTTCATCGA, and the control siRNA sequence was GATAAGAACAGCGGCTATA.

Lentivirus vector particles were produced by calcium phosphate transient cotransfection of 293T cells by the vector plasmid, an encapsidation plasmid (p8.9), and a vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) expression plasmid (pHCMV-G) as described previously (21). The viral particles were concentrated by ultracentrifugation, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in PBS, divided into aliquots, and frozen at −80°C until use. EGFP-expressing viruses were titered by infecting neurons with serial dilutions of each lentiviral stock. The percentage of transduced cells, identified by EGFP fluorescence, was estimated 72 h post-transfection and used to determine the number of transducing units (TU) per unit volume.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± se. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using the Student’s t test and the Microsoft Excel program (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

RESULTS

DHHC-3, -8, HIP14L, and HIP14 reside in the Golgi compartment

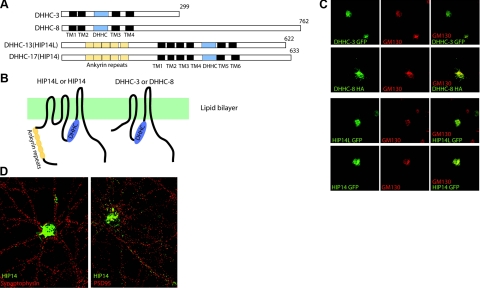

Twenty-three DHHC-containing proteins have been identified recently. Four that are enriched in the brain were chosen for our study here. Previous studies revealed that DHHC-3 (also named GODZ) localizes to the Golgi apparatus (22) and has enzyme activity toward glutamate receptors (23) and the GABAA receptor γ2 subunit (12). Mutations in the DHHC-8 gene have been linked to bipolar disorder and schizophrenia in certain ethnic groups (24, 25). DHHC-13 (also named HIP14L) shares 48% identity and 57% similarity with HIP14 (DHHC-17) (26). HIP14 is concentrated primarily in the Golgi apparatus but also associates with endosomal vesicles in soma and processes (6, 26). It was shown previously that HIP14 controls palmitoylation and trafficking of several mammalian neuronal proteins (6). Recent studies revealed that exogenous HIP14 is localized at presynaptic terminals in Drosophila motor neurons and controls transmitter release by palmitoylating SNAP25 and cysteine string proteins (27, 28). Overall, the homology among these four DHHC proteins is restricted to the cysteine rich domain, as is shown in the schematic illustration (Fig. 1A, B). For example, the ankyrin repeat domain, which is common to DHHC-13 and HIP14, is not found in either DHHC-3 or DHHC-8.

Figure 1.

Structures and localizations of four neuronal DHHC proteins. A) Schematic illustration of the primary structures of the four DHHC proteins, DHHC-3, DHHC-8, DHHC-13 (HIP14L), and HIP14. DHHC protein family is featured by the cysteine rich domain (blue), which is surrounded by 4–6 transmembrane (TM) domains. B) Schematic illustration of the primary structures of the four DHHC proteins. C) Localization of the four DHHC proteins in COS cells. Exogenous DHHC-3, DHHC-8, HIP14L, and HIP14 (all green) colocalize with the cis-Golgi marker GM130 (red). D) Localization of HIP14 in DIV 18 hippocampal neurons. Endogenous HIP14 in these neurons does not colocalize with either a presynaptic protein marker, synaptophysin, or a postsynaptic protein marker, PSD95, which suggests that HIP14 is absent from synapses.

Despite their distinct molecular identities, when expressed in COS cells, all four PATs colocalized with the Golgi marker GM130 (Fig. 1C) but not with EEA1, an early endosomal marker, or with Calnexin, an ER marker (Supplemental Fig. 1). In d 18 cultured rat hippocampal neurons, endogenous HIP14 mainly associates with the Golgi apparatus and sparsely associates with vesicles (6). As opposed to the finding in Drosophila, coimmunostaining of endogenous HIP14 with the presynaptic marker synaptophysin or the postsynaptic marker PSD95 showed that HIP14 is not present at synapses (Fig. 1D).

DHHC-3 and -8, HIP14L, and HIP14 exhibit distinct substrate preferences

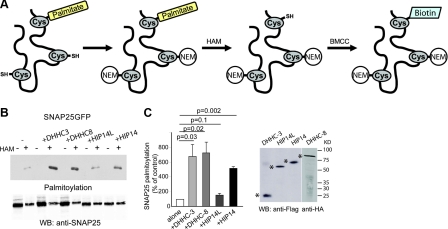

To determine the level of protein palmitoylation, we used the ABE assay (Fig. 2A). This method had been used previously to examine the palmitoylation of SNAP25 and nicotinic α7 subunits in mammals (16, 17), and then of many palmitoylated yeast proteins through proteomic analysis (3, 29). To validate this method in detecting a change in palmitoylation of a protein by an enzyme, we used SNAP25 as a substrate with coexpression of each of the four DHHC enzymes. The expression of DHHC-3, DHHC-8, HIP14L, and HIP14 were equal (Fig. 2C). The ABE assay revealed that DHHC-3, DHHC-8, and HIP14 significantly enhanced the palmitoylation of SNAP25, while HIP14L did not (Fig. 2B, lanes labeled HAM +). Samples that were not treated with hydroxylamine, and therefore did not have free cysteines able to be labeled by biotin, were not detected by strepdavidin (Fig. 2B, lanes labeled HAM−).

Figure 2.

Validation of ABE method with substrate SNAP25. A) Diagram of the ABE procedure. First, GFP-tagged SNAP25 was immunoprecipitated by GFP antibody. Next, the sepharose beads that contain SNAP25 were incubated with 50 mM NEM at 4°C for 1 h to block the free thiols. Then, 1 M hydroxylamine was used to cleave the Cys-palmitoyl thioester linkage. At last, the newly exposed free thiols were labeled with a sulfhydryl-specific labeling compound, biotin-BMCC. B) Application of ABE method in examining the enhancement of SNAP25 palmitoylation by four DHHC proteins. Palmitoylation level is detected by strepdavidin-HRP on nitrocellular membrane. Untreated samples (HAM−) were used to estimate residual, nonspecific binding of the biotin-BMCC with antibodies and sepharoses (negative control). In treated samples (HAM+), SNAP25-GFP substrate protein loading among the various samples was even, yet its palmitoylation level was enhanced to a different extent by DHHC-3, DHHC-8, and HIP14. HIP14L, in contrast, did not increase SNAP25 palmitoylation. C) Expression of DHHC-3, DHHC-8, HIP14L, and HIP14 in COS cells was approximately even. Stars indicate protein bands.

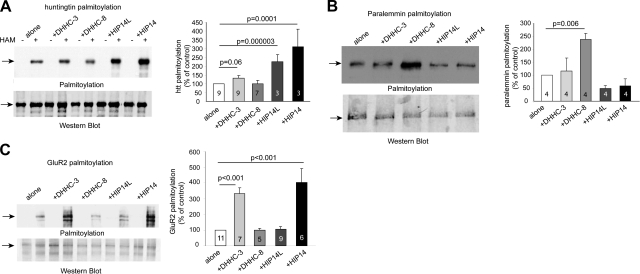

The same approach helped determine the potential substrates for these DHHC enzymes. We have demonstrated previously that huntingtin, a protein containing a polyglutamine tract expansion implicated in Huntington disease, is a substrate of HIP14 (6, 7). Using the ABE method, we now show that huntingtin can also be palmitoylated by HIP14L (DHHC-13), a protein that shares 57% similarity with HIP14 (Fig. 3A), but not by DHHC-3 and DHHC-8. Interestingly, DHHC-13 also interacts with huntingtin when coexpressed in COS cells (unpublished results). Unlike huntingtin, palmitoylation of paralemmin-1, a protein implicated in spine formation (19), is specifically enhanced only by DHHC-8 (Fig. 3B). The ABE method also confirmed that the AMPA receptor subunits GluR1 and GluR2 are substrates of DHHC3, shown previously by metabolic labeling (23) (Fig. 3C and Supplemental Fig. 2). We also found that the AMPA receptor subunits are subject to palmitoylation by HIP14. In addition to huntingtin, paralemmin-1, and AMPA receptors, we also examined the effects of these four DHHC proteins on palmitoylation of other neuronal proteins, including the GABAA receptor γ2 subunit, GAD65, and synaptotagmin VII (Supplemental Fig. 2). In accordance with published metabolic labeling results (30), palmitoylation of the GABAA receptor γ2 subunit is enhanced specifically by DHHC-3. All four DHHC proteins can enhance the palmitoylation of GAD65, whereas none appeared to regulate the palmitoylaiton of synaptotagmin VII. Taken together, these results suggest that individual palmitoyl transferases exhibit distinct substrate specificity. However, whether each DHHC enzyme recognizes its respective substrates via specific consensus motifs remains unknown.

Figure 3.

Application of ABE method to identify substrate and DHHC enzyme specificity. A) Palmitoylation of huntingtin is enhanced specifically by HIP14 and HIP14L. B) Palmitoylation of paralemmin is enhanced specifically by DHHC-8. C) Palmitoylation of the AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit is enhanced specifically by DHHC-3 and HIP14. Quantification was normalized to protein expression. Number of repeats is indicated in each column. Arrows indicate protein bands.

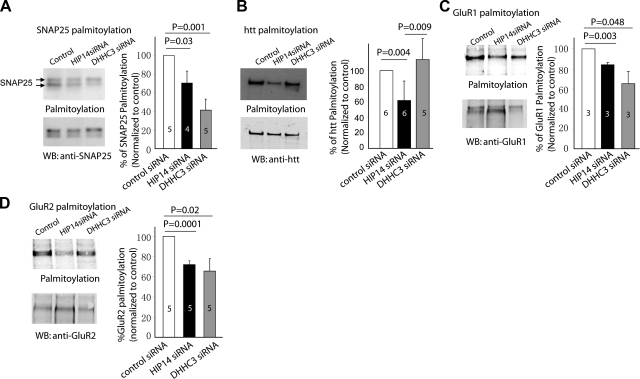

Knockdown of endogenous DHHC-3 and HIP14 in neurons confirms their substrate specificity in vivo

To determine whether the substrate specificity seen by exogenous expression of an enzyme together with a substrate reflects substrate specificities in vivo, we generated lentiviruses expressing either a scramble siRNA, DHHC-3 siRNA, or HIP14 siRNA based on previous published references (6, 30) (Supplemental Fig. 3). Previous studies have shown that HIP14 knockdown reduces the clustering of PSD95 at the synapse (6) and DHHC-3 knockdown affects the normal assembly and function of GABAergic inhibitory synapses (30). Despite this, rat cortical neurons that were infected with viruses at day in vitro (DIV) 3 for 7 to 12 d appeared healthy and showed no abnormality in gross neuronal morphology. After the neurons were harvested, the ABE assay was used to measure the palmitoylation levels of selected neuronal substrates (Fig. 4). Consistent with our observations using exogenous expression, palmitoylation of SNAP-25, GluR1, and GluR2 were reduced on knockdown of either HIP14 or DHHC-3 (Fig. 4A, C, D). In contrast, htt palmitoylation was reduced with knockdown of HIP14, but not with knockdown of DHHC-3, an enzyme that does not palmitoylate htt. In addition, palmitoylation of GAD65 and PSD95 was decreased by knocking down HIP14 but was not affected by DHHC-3 knockdown. This finding suggests that HIP14 is the major endogenous enzyme for GAD65 and PSD95 (Supplemental Fig. 4). Palmitoylation of synaptotagmin I, however, was not altered by knocking down either HIP14 or DHHC-3 (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Assessment of palmitoylation status by ABE method after knockdown of endogenous DHHC-3 and HIP14 in rat cortical neurons. A) Palmitoylation of SNAP25 is decreased significantly after HIP14 knockdown (70.8% vs. control, P=0.03) and DHHC-3 siRNA knockdown (41.4% vs. control, P=0.001). B) Palmitoylation of huntingtin is reduced after HIP14 knockdown (61.3% vs. control, P=0.004). C, D) Palmitoylation of the AMPA receptor GluR1 (C) and GluR2 subunits (D) is reduced significantly on both HIP14 and DHHC-3 knockdown in vivo. Compared to control scramble siRNA, which is normalized to 100%, palmitoylation of GluR1 is 84.5% in HIP14 siRNA-infected neurons (P=0.003) and 65.1% in DHHC-3 siRNA-infected neurons (P=0.048); palmitoylation of GluR2 is 71.9% in HIP14 siRNA-infected neurons (P=0.0001) and 65.6% in DHHC-3 siRNA-infected neurons (P=0.02).

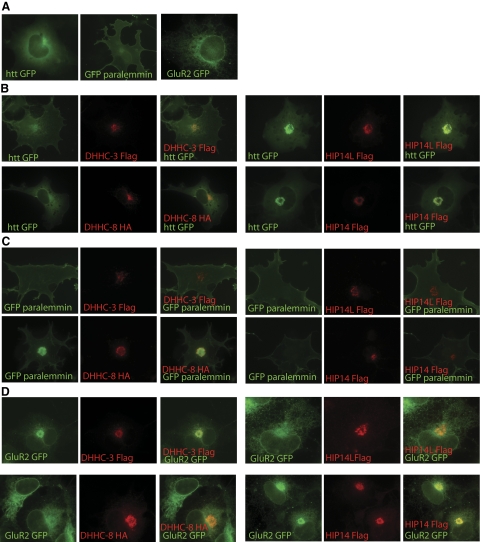

Expression of DHHC proteins alters the distribution and trafficking of their respective substrates

Previous studies showed that palmitoylation targets PSD-95 to a perinuclear domain (31). In agreement with this finding, we showed previously that HIP14 enhances palmitoylation-dependent vesicular trafficking of huntingtin to the perinuclear region in both COS cells and neurons (6). In addition, Fukata et al. (11) demonstrated that DHHC-15, a PSD95 PAT, increased the segregation of PSD-95 to a perinuclear region. In this study, we also found that HIP14L and HIP14 enhanced perinuclear accumulation of huntingtin, while DHHC-3 and DHHC-8 did not (Fig. 5A). Paralemmin-1 specifically accumulated in a perinuclear domain when coexpressed with DHHC-8, but not with DHHC-3, HIP14L, or HIP14 expression (Fig. 5B). Accumulation of GluR2 in the perinuclear domain was mediated specifically by DHHC-3 and HIP14 but not by DHHC-8 or HIP14L (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these results indicate that PATs play two closely related roles, regulation of palmitoylation and modulation of vesicular trafficking.

Figure 5.

DHHC enzymes modulate trafficking of their respective palmitoylated substrates. A, B) Huntingtin alone localizes to the cytoplasm in a diffuse pattern. Exogenous HIP14L and HIP14 enhance the trafficking of huntingtin into a perinuclear region, where enzyme and huntingtin colocalize. A, C) Paralemmin alone predominantly localizes to the plasma membrane and slightly to the Golgi. Exogenous DHHC-8 enhances the trafficking of paralemmin into the perinuclear region where they colocalize. A, D) Exogenous DHHC-3 and HIP14 also enhance the trafficking of GluR2 into the perinuclear region.

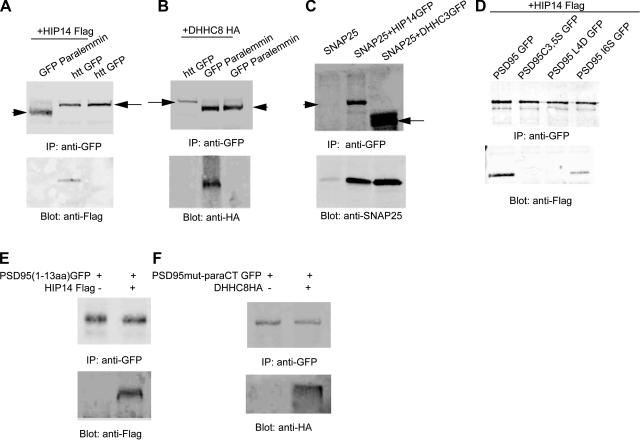

DHHC enzymes interact with their respective substrates

Mounting evidence suggests that an interaction exists between a substrate and its potential PAT. The interaction may be transient and mediated by palmitate when the enzyme transfers palmitate to the substrate. Alternatively, it may be a long-term protein–protein interaction, as in the case of huntingtin and HIP14, which is mediated by the ankryin repeat domain (26). Previous results from several groups have shown that DHHC-3 interacts with its substrates GABAA receptor γ2 subunit and AMPA receptors when expressed in heterologous cell lines (12, 22). In another study, putative enzymes that palmitoylate endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) interact with eNOS (32).

The next question was whether the four PATs specifically interact with their substrates and whether this can be used as a new approach for identifying putative enzyme–substrate interactions. As seen in Fig. 6A, when GFP-paralemmin or huntingtin-GFP were overexpressed with HIP14, HIP14 was found in association with huntingtin but not with paralemmin. Likewise, when DHHC-8 was overexpressed with GFP-paralemmin or huntingtin-GFP, DHHC-8 was found interact only with paralemmin (Fig. 6B). In addition, SNAP-25 interacts with its PATs DHHC-3 and HIP14 (Fig. 6C).These results indicate that the interaction is rather specific to the enzyme and its respective substrates. Next, whether palmitoylation of a specific substrate is essential for its interaction with its respective enzyme was examined. Previous work demonstrated that palmitoylation of PSD-95 is mediated by a short NH2-terminal consensus sequence that critically relies on five consecutive hydrophobic amino acids (Cys-Leu-Cys-Ile-Val) (31). Mutations of both cysteines abolished PSD95 palmitoylation. Mutating amino acids 4-Leu or 6-Ile to histidine and serine, respectively (L4D, I6S) also significantly reduced palmitoylation (31). Interestingly, the interactions between these PSD95 mutants and HIP14 are also altered, correlating with their level of palmitoylation (31) (Fig. 6D). This result suggests that the amino acids flanking palmitoylated cyteines are likely to be critical for the interaction of the enzyme and substrate.

Figure 6.

DHHC enzymes specifically interact with their respective palmitoylated substrates. A) Huntingtin, but not paralemmin, interacts with HIP14. COS cells overexpressing huntingtinGFP alone, huntingtinGFP with HIP14Flag, and paralemminGFP with HIP14Flag were lysed and subjected to immunoprecipitation by GFP antibody. Western blot was probed with Flag antibody to detect whether HIP14 Flag was associated with the substrates. Arrow, httGFP; arrowhead, GFP paralemmin. B) Conversely, paralemmin, but not huntingtin, interacts with DHHC-8. Arrow, httGFP; arrowhead, GFP paralemmin. Coimmunoprecipitation procedure was the same as in A. C) SNAP25 coimmunoprecipitates with its palmitoylating enzymes DHHC-3 and HIP14. Arrow, DHHC3 GFP; arrowhead, HIP14 GFP. D) Interaction of HIP14 and PSD95 requires the dual palmitoylated cysteines and the nearby amino acids. E) PSD95 palmitoylation motif, containing aa 1–13, is sufficient to interact with HIP14. F) An artificial construct that contains the C-terminal 12-aa paralemmin pamitoylation motif is sufficient to interact with DHHC-8.

The next question was whether the palmitoylated motif of a substrate is sufficient for its interaction with the enzyme. Previous work identified that the first 13 amino acids of PSD95 are essential for its palmitoylation and correct vesicular sorting (31). Consistent with this, we also found that this short N-terminal motif of PSD95 is sufficient for its interaction with HIP14 when exogenously expressed in COS cells (Fig. 6E). To confirm further that DHHC enzymes recognize the palmitoylation motif, we made a chimeric protein containing the full-length PSD95 C3,5S (palm-deficient mutant) and 12 amino acids of the paralemmin carboxyl terminus containing its palmitoylated cysteines. A coimmunoprecipitation experiment showed that this new protein, containing only the palmitoylation motif of paralemmin, interacts with DHHC-8, the PAT that palmitoylates paralemmin (Fig. 6F).

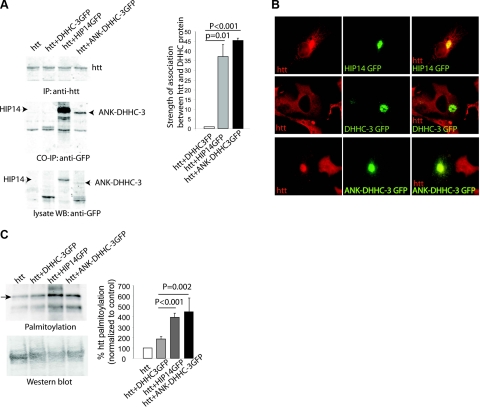

Regions distinct from the DHHC catalytic domain of the enzymes determine the specificity between substrates and enzymes

Unlike DHHC-3 and DHHC-8, huntingtin palmitoylating enzymes HIP14 and HIP14L contain an ankryin repeat domain that interacts with an N-terminal fragment of huntingtin (26). To determine whether the ankyrin repeat domain within HIP14 plays a crucial role in palmitoylating huntingtin, we made a new chimeric protein with ankryin repeat domain fused to DHHC-3 (ANK-DHHC-3). This chimeric protein, which mimics the HIP14 structure, can interact with huntingtin and redistribute huntingtin into a perinuclear region via palmitoylation dependent vesicular trafficking (Fig. 7A, B). Remarkably, this chimera can enhance the palmitoylation of huntingtin in COS cells to the same extent as HIP14 (Fig. 7C). To confirm that this chimera acts through altered specificity rather than a loosening of substrate specificity, we also tested the chimera’s enzymatic activity toward GluR2 and paralemmin. GluR2 is a substrate for both DHHC-3 and HIP14 and is also palmitoylated by ANK-DHHC-3 to a similar extent (Supplemental Fig. 5A, B). In contrast, paralemmin, a substrate of neither DHHC-3 nor HIP14, is not palmitoylated by ANK-DHHC-3 (Supplemental Fig. 5C, D). These results suggest that regions other than the DHHC domain of the enzyme determine the specificity between substrates and enzymes.

Figure 7.

Substrate specificity is determined by specific domains of the DHHC enzymes. A) Chimeric protein composed of ankyrin repeats and full-length DHHC-3 can interact with huntingtin. Strength of the interaction of ANK-DHHC-3 with huntingtin is comparable to that of HIP14 with huntingtin. B) New chimeric protein ANK-DHHC-3 can accumulate huntingtin into a perinuclear region. C) New chimeric protein ANK-DHHC-3 can also palmitoylate huntingtin in COS cells. All quantifications were normalized to protein expression.

DISCUSSION

The number of DHHC PATs suggests that substrate specificity may be present for each PAT. In yeast, loss-of-function analysis mapped the potential substrates of each DHHC enzyme (3). Our study, along with others, indicates that mammalian DHHC enzymes also have substrate specificity (33). Compelling evidence has revealed that DHHC-3 and the closely related DHHC-7 have the broadest substrate specificity (33). These two DHHC enzymes enhance the palmitoylation of various substrates, including PSD95, eNOS, the GABAA receptor γ2 subunit, SNAP25, Gαs, and GAP43 (11, 30, 32, 34). DHHC-3 also enhances the palmitoylation of GluR receptors (23). In contrast, DHHC-2 and DHHC-15 are more specific to PSD95 and GAP43 (11). HIP14 (DHHC-17) palmitoylates huntingtin but also increases palmitoylation of SNAP25, PSD95, GAD65, and synaptotagmin I (6). DHHC-8 is specific to paralemmin, and DHHC-9 and DHHC-18 are specific to H-Ras (11, 35). Taken together, these data clearly support differential substrate specificity of individual PATs.

However, the determinants of the specificity between enzymes and substrates remain elusive. One possibility is that the subcellular localization of each DHHC protein plays a role in its substrate specificity such that if substrates share the same compartments during post-translational modification and transport, palmitoylation can occur. Indeed, the 23 DHHC enzymes showed a number of distinct expression patterns in HEK cells (14). However, the four DHHC proteins examined in this study all localize to the Golgi compartment, yet exhibit distinct substrate preferences, which suggests that other factors may contribute to enzyme-substrate specificity.

In this study, we have utilized the ABE method to examine the level of protein palmitoylation. The major disadvantage of the traditional metabolic labeling method is that 3H palmitate only labels the pool of protein that turns over during the 3–4 h of labeling process. Therefore, if the half-life of palmitate turnover on a substrate is longer than the labeling hours, then only a proportion of the total palmitoylated protein pool is labeled with 3H palmitate. Thus, the 3H palmitate signal detected on the film does not reflect the total palmitoylated protein pool, and it may not be correlated linearly to the total palmitoylated protein. Therefore, we postulated that it is possible that two different methods may show different or even opposing results.

It has been shown that PSD-95 transiently associates with a perinuclear membranous compartment and traffics with vesiculotubular structures (31). Trafficking of PSD-95 with these vesiculotubular structures requires dual palmitoylation. In many examples, palmitoylation of a substrate by an enzyme correlates with the ability of the enzyme to enhance the association of the substrate with perinuclear membraneous compartment and vesiculotubular structures (6, 11). This is exemplified by HIP14 with AMPA receptors, huntingtin, SNAP25 and PSD95, DHHC8 with paralemmin, DHHC3 with AMPA receptors (22), GABAA receptor γ2 subunit (12), and DHHC-15 with PSD95 (11). Therefore, the recruitment of a substrate into the perinuculear compartment by an enzyme can help predict the putative enzyme-substrate relationship.

Immunofluorescent staining of endogenous HIP14 reveals it is predominantly localized in the Golgi compartment and is not enriched at the synapse where HIP14 substrates PSD95 and AMPA receptors reside (Fig. 1D). Therefore, synapses are not likely the major sites where HIP14 palmitoylates these substrates. However, previous studies using electron microscopic (EM) analysis and time-lapse imaging have revealed that HIP14 is associated with the cytosolic side of diverse vesicular structures present in the soma and dendrites (6). The association of HIP14 with several vesicular compartments that may include recycling and late endosomes indicates that these sites are potentially where HIP14 palmitoylates substrates that do not travel through Golgi, including PSD95. Once PSD95 is transported to the synapse, DHHC enzymes that localize to the plasma membrane or spines are potential candidate for the dynamic palmitoylation of PSD95 at the synapse.

We also revealed the specificity of the interaction between an enzyme and a substrate by coimmunoprecipitation. The stable interaction of an enzyme and its substrate is likely to be palmitoylation-dependent, as mutations of palmitoylated cysteines abolish the interaction. It is intriguing that the palmitoylation motif is sufficient to be recognized by the respective enzyme, which suggests that a consensus sequence may exist. However, whereas, these DHHC enzymes readily form a stable complex on overexpression with their respective substrates in heterologous cells, only huntingtin and HIP14 interaction, but no other complex could be detected in brain extracts (refs. 7, 12, 22 and data not shown). Therefore, such stable complexes such as SNAP25 and HIP14 detected in overexpression experiments might represent long-lived enzymatic reaction intermediates resulting from low catalytic processing of enzymes in heterologous cells (also in ref. 30). Nevertheless, the stable interaction between the DHHC proteins and substrates is useful for predicting the putative enzyme-substrate relationship.

What determines the specificity and whether palmitoylation consensus sequences exist are not yet known. Previous analyses have prompted the classification of 23 DHHC proteins into several subfamilies. Some structural correlations to enzyme specificity may exist. Besides the catalytically critical DHHC domain, an individual DHHC protein may have regulatory regions such as the SH3 domain in DHHC6, ankyrin repeats in HIP14 and DHHC-13 (HIP14L), and type II PDZ-binding motif in DHHC-3 (33) (similarly, protein kinases also share a core catalytic region and differ in regulatory domains that afford differential control systems). Conceivably, these regions may recruit specific substrates or regulators to DHHC proteins. This possibility is exemplified by our result showing that fusing the ankyrin repeats to DHHC3 enables DHHC-3 to behave like HIP14, interacting with and palmitoylating huntingtin.

PATs may require binding partners to be functionally active. This possibility was first shown in yeast, where the yeast DHHC protein Erf2 functions as a PAT for yeast Ras2 in a complex with Erf4 (36). Recently, Swarthout et al. (35) found that DHHC9 requires GCP16, a mammalian functional ortholog of Erf4, for its PAT activity toward H/N-Ras and protein stability. Binding partners of DHHC proteins may also contribute to the substrate specificity, enzymatic kinetics, subcellular localization, and stability of some DHHC proteins as an auxiliary subunit.

It is noteworthy that palmitoylation catalysis of a substrate by a DHHC enzyme also seems to require its autopalmitoylation. For example, deletion of the HIP14 DHHC domain, which abolishes HIP14 autopalmitoylation, also abrogates its ability to palmitoylate SNAP25 (6). Mutations or deletions such as AAHC-15, DHHC-15-C159S, or DHHC-15-ΔC (aa 1–238) in the PAT for PSD-95, DHHC-15, results in loss of autopalmitoylation and loss of its palmitoyl transferase activity (11). These examples support the notion that the PAT activity of a DHHC enzyme correlates with its autopalmitoylation.

To determine definitively the in vivo specificity of palmitoylation substrate for each enzyme, additional tools such as the use of specific small interference RNAs as in this study or the generation of mice with targeted disruption of DHHC proteins will be mandatory. Nonetheless, with data in this manuscript, we have demonstrated that neuronal PATs have distinct substrate specificity both in vitro and in vivo. One factor that contributes to this specificity is the regulatory domain in addition to the catalytic DHHC domain. We also have identified a consistent correlation between palmitoylation, altered distribution of a substrate by its DHHC enzyme, and the interaction between them. These detailed analyses provide further understanding into the relationship of DHHC enzymes and their putative substrates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of our dear colleague and mentor Dr. Alaa El-Hussseini, who tragically died during the completion of the work for this manuscript. We thank Esther Yu for her excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grants to A.E.H. from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR), the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR), and the High Q Foundation. A.E.H. was an MSFHR senior scholar. M.R.H. is Canada Research Chair in Human Genetics and Molecular Medicine and is supported by CIHR, MSFHR, the High Q Foundation, the Heart and Stroke Foundation, the Huntington Society of Canada, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

References

- El-Husseini A D, Bredt D S. Protein palmitoylation: a regulator of neuronal development and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:791–802. doi: 10.1038/nrn940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resh M D. Palmitoylation of ligands, receptors, and intracellular signaling molecules. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:re14. doi: 10.1126/stke.3592006re14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A F, Wan J, Bailey A O, Sun B, Kuchar J A, Green W N, Phinney B S, Yates J R, 3rd, Davis N G. Global analysis of protein palmitoylation in yeast. Cell. 2006;125:1003–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K, El-Husseini A. Modulation of neuronal protein trafficking and function by palmitoylation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:527–535. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder M E, Deschenes R J. Palmitoylation: policing protein stability and traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:74–84. doi: 10.1038/nrm2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K, Yanai A, Kang R, Arstikaitis P, Singaraja R R, Metzler M, Mullard A, Haigh B, Gauthier-Campbell C, Gutekunst C A, Hayden M R, El-Husseini A. Huntingtin-interacting protein HIP14 is a palmitoyl transferase involved in palmitoylation and trafficking of multiple neuronal proteins. Neuron. 2004;44:977–986. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanai A, Huang K, Kang R, Singaraja R R, Arstikaitis P, Gan L, Orban P C, Mullard A, Cowan C M, Raymond L A, Drisdel R C, Green W N, Ravikumar B, Rubinsztein D C, El-Husseini A, Hayden M R. Palmitoylation of huntingtin by HIP14 is essential for its trafficking and function. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:824–831. doi: 10.1038/nn1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. The Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group Cell. 1993;72:971–983. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Husseini A D, Schnell E, Dakoji S, Sweeney N, Zhou Q, Prange O, Gauthier-Campbell C, Aguilera-Moreno A, Nicoll R A, Bredt D S. Synaptic strength regulated by palmitate cycling on PSD-95. Cell. 2002;108:849–863. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo S, Greentree W K, Linder M E, Deschenes R J. Identification of a Ras palmitoyltransferase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41268–41273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukata M, Fukata Y, Adesnik H, Nicoll R A, Bredt D S. Identification of PSD-95 palmitoylating enzymes. Neuron. 2004;44:987–996. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C A, Yuan X, Panzanelli P, Martin M L, Alldred M, Sassoe-Pognetto M, Luscher B. The gamma2 subunit of GABA(A) receptors is a substrate for palmitoylation by GODZ. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5881–5891. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1037-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A F, Feng Y, Chen L, Davis N G. The yeast DHHC cysteine-rich domain protein Akr1p is a palmitoyl transferase. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:23–28. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno Y, Kihara A, Sano T, Igarashi Y. Intracellular localization and tissue-specific distribution of human and yeast DHHC cysteine-rich domain-containing proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:474–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resh M D. Use of analogs and inhibitors to study the functional significance of protein palmitoylation. Methods. 2006;40:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drisdel R C, Green W N. Labeling and quantifying sites of protein palmitoylation. BioTechniques. 2004;36:276–285. doi: 10.2144/04362RR02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drisdel R C, Manzana E, Green W N. The role of palmitoylation in functional expression of nicotinic alpha7 receptors. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10502–10510. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3315-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drisdel R C, Alexander J K, Sayeed A, Green W N. Assays of protein palmitoylation. Methods. 2006;40:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arstikaitis P, Gauthier-Campbell C, Gutierrez Herrera R C, Huang K, Levinson J N, Murphy T H, Kilimann M W, Sala C, Colicos M A, El-Husseini A. Paralemmin-1, a modulator of filopodia induction is required for spine maturation. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2026–2038. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang R, Swayze R, Lise M F, Gerrow K, Mullard A, Honer W G, El-Husseini A. Presynaptic trafficking of synaptotagmin I is regulated by protein palmitoylation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50524–50536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404981200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria J, Khalfallah O, Sauty C, Brunet I, Sibieude M, Mallet J, Berrard S, Lecomte M J. Silencing of choline acetyltransferase expression by lentivirus-mediated RNA interference in cultured cells and in the adult rodent brain. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:532–544. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura T, Mori H, Mishina M. Isolation and characterization of Golgi apparatus-specific GODZ with the DHHC zinc finger domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:492–496. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00900-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Rumbaugh G, Huganir R L. Differential regulation of AMPA receptor subunit trafficking by palmitoylation of two distinct sites. Neuron. 2005;47:709–723. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai J, Liu H, Burt R A, Swor D E, Lai W S, Karayiorgou M, Gogos J A. Evidence that the gene encoding ZDHHC8 contributes to the risk of schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2004;36:725–731. doi: 10.1038/ng1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul T, Gawlik M, Bauer M, Jung S, Pfuhlmann B, Jabs B, Knapp M, Stober G. ZDHHC8 as a candidate gene for schizophrenia: analysis of a putative functional intronic marker in case-control and family-based association studies. BMC Psych. 2005;5:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-5-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singaraja R R, Hadano S, Metzler M, Givan S, Wellington C L, Warby S, Yanai A, Gutekunst C A, Leavitt B R, Yi H, Fichter K, Gan L, McCutcheon K, Chopra V, Michel J, Hersch S M, Ikeda J E, Hayden M R. HIP14, a novel ankyrin domain-containing protein, links huntingtin to intracellular trafficking and endocytosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2815–2828. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.23.2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama T, Verstreken P, Ly C V, Rosenmund T, Rajan A, Tien A C, Haueter C, Schulze K L, Bellen H J. Huntingtin-interacting protein 14, a palmitoyl transferase required for exocytosis and targeting of CSP to synaptic vesicles. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:1481–1496. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowers R S, Isacoff E Y. Drosophila huntingtin-interacting protein 14 is a presynaptic protein required for photoreceptor synaptic transmission and expression of the palmitoylated proteins synaptosome-associated protein 25 and cysteine string protein. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12874–12883. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2464-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam K K, Davey M, Sun B, Roth A F, Davis N G, Conibear E. Palmitoylation by the DHHC protein Pfa4 regulates the ER exit of Chs3. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:19–25. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang C, Deng L, Keller C A, Fukata M, Fukata Y, Chen G, Luscher B. GODZ-mediated palmitoylation of GABA(A) receptors is required for normal assembly and function of GABAergic inhibitory synapses. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12758–12768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4214-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Husseini A E, Craven S E, Chetkovich D M, Firestein B L, Schnell E, Aoki C, Bredt D S. Dual palmitoylation of PSD-95 mediates its vesiculotubular sorting, postsynaptic targeting, and ion channel clustering. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:159–172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Hernando C, Fukata M, Bernatchez P N, Fukata Y, Lin M I, Bredt D S, Sessa W C. Identification of Golgi-localized acyl transferases that palmitoylate and regulate endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:369–377. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi R, Fukata Y, Fukata M. Discovery of protein-palmitoylating enzymes. Pflügers Arch. 2008;456:1199–1206. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0465-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi R, Fukata Y, Noritake J, Iwanaga T, Perez F, Fukata M. Identification of G protein α subunit-palmitoylating enzyme. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:435–447. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01144-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarthout J T, Lobo S, Farh L, Croke M R, Greentree W K, Deschenes R J, Linder M E. DHHC9 and GCP16 constitute a human protein fatty acyltransferase with specificity for H- and N-Ras. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31141–31148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Lobo S, Dong X, Ault A D, Deschenes R J. Erf4p and Erf2p form an endoplasmic reticulum-associated complex involved in the plasma membrane localization of yeast Ras proteins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49352–49359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.