Abstract

Selenium is an essential micronutrient for humans and animals, and its deficiency can predispose to the development of pathological conditions. This study evaluates the effect of selenium deficiency on the thioredoxin system, consisting of NADPH, selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase (TrxR), and thioredoxin (Trx); and the glutathione system, including NADPH, glutathione reductase, glutathione, and glutaredoxin coupled with selenoprotein glutathione peroxidase (GPx). We particularly investigate whether inactive truncated TrxR is present under selenium-starvation conditions due to reading of the UGA codon as stop. Feeding rats a selenium-deficient diet resulted in a large decrease in activity of TrxR and GPx in rat liver but not in the levels of Trx1 and Grx1. However, selenium deficiency induced mitochondrial Grx2 10-fold and markedly changed the expression of some flavoproteins that are involved in the cellular folate, glucose, and lipid metabolism. Liver TrxR mRNA was nearly unchanged, but no truncated enzyme was found. Instead, a low-activity form of TrxR with a cysteine substituted for the penultimate selenocysteine in the C-terminal active site was identified in selenium-deficient rat liver. These results show a novel mechanism for decoding the UGA stop codon, inserting cysteine to make a full-length enzyme that may be required for selenium assimilation.—Lu, J., Zhong, L., Lönn, M. E., Burk, R. F., Hill, K. E., Holmgren, A. Penultimate selenocysteine residue replaced by cysteine in thioredoxin reductase from selenium-deficient rat liver.

Keywords: selenoprotein, UGA codon, glutaredoxin

Selenium is an essential trace element involved in numerous biological processes. Its biological functions have been attributed primarily to selenoproteins, where selenium is present in the primary structure as selenocysteine (Sec, U). In the human genome, 25 selenoprotein genes have been identified, and selenium is incorporated into the selenoprotein polypeptide chain as Sec by a complex machinery cotranslationally using the UGA codon, which normally operates as a translation termination code (1, 2). Selenium deficiency has been linked firmly to one disease, a pediatric cardiomyopathy in China named Keshan disease, and is proposed to underlie other diseases, including increased cancer and infection risk and male infertility (2, 3).

The thioredoxin system, which consists of NADPH, selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase (TrxR), and thioredoxin (Trx), and the glutathione system, which includes NADPH, glutathione reductase (GR), glutathione (GSH), and glutaredoxin (Grx) coupled with glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and glutathione transferase (GST), catalyze the reduction of protein disulfides, such as in ribonucleotide reductase, methionine sulfoxide reductase, and Trx-dependent peroxidases (peroxiredoxin), and thus participate in DNA synthesis or defense against oxidative stress (4,5,6,7). The Trx system is involved in the regulation of gene expression via transcription factors and signaling molecules, including NF-κB, Ref-1, AP-1, P53, HIF-1α, glucocorticoid receptor, and apoptosis-regulating kinase (ASK1), and therefore plays a critical role in a wide range of cellular activities, such as cell proliferation, cell death, and immune response activation (8, 9).

Mammalian TrxR is a member of the pyridine nucleotide-disulfide oxidoreductase family and the only enzyme that can reduce oxidized Trx. This dimeric flavoenzyme was originally purified to homogeneity from rat liver (10) and shown to be a selenoprotein in 1996 (11). Rat TrxR1 has two identical subunits of 499 residues homologous to GR with a head-to-tail arrangement, each with an FAD domain, an NADPH binding domain, an interphase domain, and a penultimate Sec residue in a 16-residue C-terminal extension (12,13,14). Because of the high reactivity of Sec and the accessible location of the C-terminal active site, TrxR possesses a wide substrate specificity (2).

It is known that selenium depletion will cause the loss of activity of selenoproteins, including TrxR and GPx (15). However, the effect of selenium deficiency on the overall Trx and GSH systems and subsequent cellular redox state is not well understood. In particular, mammalian TrxR, which is essential for embryogenesis (16, 17), has also been shown to be a vital factor in cancer development and has become a potent target of cancer therapeutics and chemoprevention (18, 19). Furthermore, the form of TrxR is critical for its biological function. TrxR is the only mammalian selenoprotein that has been obtained recombinantly in Escherichia coli using the species-specific bacterial selenoprotein synthesis machinery (20). Both full-length and truncated TrxR lacking the last amino acid residues UG were produced in E. coli. The inactive truncated TrxR is known to induce cancer cell apoptosis, but the full-length will not (21). Since mRNA for TrxR is present, we wanted to see which form of TrxR exists under selenium-deficient conditions. Here we did not find the truncated form but surprisingly identified a low-activity form of TrxR with a cysteine substituted for Sec in selenium-deficient rat liver. This finding suggests that a unique adaptive mechanism occurs to maintain activity of this important housekeeping protein to some degree to preserve Trx functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Bio-Rad DC protein reagents were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Sundbyberg, Sweden). Bovine serum albumin from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as the protein standard. Human wild-type and mutant Trx (C61S/C72S) and goat anti-Grx1 antibodies and goat anti-Trx antibodies were from IMCO Ltd (Stockholm, Sweden; http://www.imcocorp.se). Anti-actin antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Bovine and rat cytosolic TrxRs were homogenous preparations (10, 22). The rat TrxR antibodies from a rabbit were prepared as described previously (23). All other reagents used were analytical grade.

Animal feeding

Weanling male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were fed ad libitum a Torula yeast-based selenium-deficient diet or the same diet supplemented with 0.25 mg Se/kg as sodium selenate (24). They were housed in a room with a 12:12 h light-dark cycle, and tap water was provided ad libitum. Rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (65 mg/kg body weight administered intraperitoneally) and exsanguinated by aortic puncture. Blood was treated with disodium EDTA (1 mg/ml) to prevent coagulation. The blood was centrifuged, and plasma was removed and frozen at −80°C. Liver, kidney, and brain were harvested within minutes of exsanguination and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissues were stored at −80°C until used for enzyme studies or RNA isolation. All animal experiments were performed at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and approved by the institutional animal care and use committee.

Preparation of cytosolic proteins

Homogenates of liver, kidney, and brain (10%) were prepared in 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.5. The homogenates were centrifuged at 105,000 g for 1 h. The supernatants were buffer exchanged 3 times with 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, containing 1 mM EDTA, using an Ultrafree-MC Centrifugal Filter Unit (10,000 MW limit; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Retained proteins were transferred to a 1.5-ml centrifuge tube and heated for 10 min at 56°C. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 30 min, the supernatant was transferred to a clean tube and used for enzyme assays. Protein was measured using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay or the Pierce BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

Enzyme assays

TrxR activity was measured by spectrophotometric assay of Trx-dependent insulin reduction (10, 25). The reaction solution contains 5 μM human Trx mutant (C61S/C72S), 100 μM insulin, 0.2 mM NADPH, and 5 mM EDTA in 0.1 M HEPES buffer, pH 7.6. The reaction was started by addition of the cytosol. After a 60-min incubation at room temperature, the reaction was terminated with 500 μl of 1 mM DTNB in 8 M guanidine-HCl and 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.6. A reaction solution without Trx was used as the blank to remove the effect of thiol groups in cytosolic proteins. TrxR activity was represented by the absorbance at 412 nm, the maximum absorbance of free TNB with an extinction coefficient 13.6 mM−1·cm−1.

Measurement of Trx activity was similar to that described above for TrxR (10, 25). The reaction mixture contained 100 μM insulin, 0.2 mM NADPH, 5 mM EDTA, and 200 nM bovine TrxR in 0.1 M HEPES buffer, pH 7.6 (26). The reaction was started by addition of the cytosolic proteins. After incubation at room temperature for 60 min, the reaction was terminated by addition of 500 μl of 8 M guanidine-HCl with 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, containing 1 mM DTNB. A sample without TrxR was used as the blank, and Trx activities were represented by absorbance at 412 nm/mg protein.

Glutaredoxin activity was measured with the β-hydroxyethyl disulfide (HED) assay (27, 28). The assay mixture consisted of 0.2 mM NADPH, 1 mM GSH, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, and 8 μg/ml yeast GR in 0.1 M HEPES buffer, pH 7.6. To 2 cuvettes, each containing 500 μl of assay mixture, 25 μl of 15 mM HED was added to give a final concentration of 0.7 mM. The absorbance at 340 nm was followed for 3 min at 25°C in order to ensure that both cuvettes were balanced with respect to the nonenzymatic reaction between GSH and HED. Then, the cytosolic protein was added to the sample cuvette, while an equal volume of buffer was added to the reference cuvette. The decrease in absorbance at 340 nm was followed for 3 min. The results are expressed as the change in A340 min−1·mg protein−1.

Glutathione peroxidase activity was measured in 105,000 g supernatant from the 10% homogenate. The method used has been described previously (29). Hydrogen peroxide (0.25 mM) was used as substrate.

Western blotting

The 85% ammonium sulfate precipitates of liver homogenates from selenium-deficient and control rats were dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5 (TE buffer) to remove the salt. Then 30 μg of protein was separated on a 12% Bis-Tris gel with MES running buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The rat TrxR was detected by the antibodies from a rabbit (1:1000 dilution) (23). Grx1 and Trx1 were detected with goat anti-Grx1 antibodies and goat anti-Trx1 antibodies at dilutions of 1:200 and 1:1000, respectively, followed by detection with Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Shelton, CT, USA).

Measurement of Grx2 amount by ELISA

Levels of Grx2 in liver extract from control vs. selenium-deprived rats were assayed and compared using a specific sandwich ELISA as described by Lundberg et al. (30). In brief, a 96-well plate was coated with affinity-purified antibodies for human Grx2 (2 μg/ml) and left to incubate overnight at 4°C. After 2 h of blocking with 10 mg/ml BSA, a standard (0.05–50 ng/ml) of human Grx2 protein and cell extract was allowed to react with the antibodies overnight at 4°C. Incubation with affinity-purified biotinylated human Grx2 antibodies was followed by incubation with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (Dako, Glostrup, Danmark). After adding p-nitrophenyl phosphate, quantification was performed using a multiplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 405 nm. Since both the antibodies as well as the standard were of human origin, no absolute values could be calculated.

RNA analysis

Total RNA was isolated from tissues as described previously (31). Following separation on formaldehyde-agarose gel, the RNA was transferred to nitrocellulose using a Bio-Rad transfer apparatus and 10× SSC (1× SSC contains 0.15 M NaCl and 0.015 M sodium citrate). The RNA was attached to nitrocellulose by UV cross-linking. After prehybridization for 2 h at 42°C in hybridization buffer containing 50% formamide, 10× Denhardt’s, 0.1% SDS, 5× SSC, salmon sperm DNA (0.25 mg/ml), and polyadenylic acid (0.5 mg/ml), the filter was hybridized overnight at 42°C with 32P-labeled cDNA probe. The filter was rinsed briefly with 2× SSC and washed with 0.5× SSC for 1 h at 50°C. After exposure to film (Kodak XAR-5; Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA), the filter was stained with methylene blue according to a previously published procedure (32). The autoradiograph and methylene blue filters were scanned with an Apple OneScanner (Apple Computer, Cupertino, CA, USA), and the scanned data were quantitated using NIH Image software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) on an Apple Macintosh 6500/250. cDNA probes used were: 16C1 for selenoprotein P (33), GPXP01 for GPX1 (kindly provided by Dr. Nobumasa Imura of Kitasato University, Tokyo, Japan), the open reading frame of rat TrxR1 cDNA (22), the open reading frame of human Trx-1 (Trx1) cDNA (23, 34), and the open reading frame of human glutaredoxin cDNA (35).

Separation of rat liver TrxR by 2′5′-ADP Sepharose chromatography

The ammonium sulfate precipitates (30 g) of liver homogenates from selenium-deficient and control rats were dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5 (TE buffer), to remove the salt. Then the samples were applied to a 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose column (1.1×12.5 cm for control samples; 1.1×10.0 cm for selenium-deficient samples). After washing the column with 5 vol of TE buffer containing 50 mM NaCl, the bound proteins were eluted with a gradient of 0.05 to 0.5 M NaCl in TE buffer. Protein concentration was monitored by the absorbance at 280 nm, and TrxR activity was measured by DTNB reduction (36). The selected faction (10 μl) was incubated with SDS-loading buffer with 50 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) at 60°C for 30 min and then separated on 12% Bis-Tris gels with MES running buffer, and the gels were stained by Coomassie blue R-250. For the sample from control rats, lanes 1-21 corresponded to elution volumes of 17.0, 18.7, 20.4, 22.1, 23.8, 25.5, 27.2, 28.9, 30.5, 32.1, 34.3, 36.0, 37.0, 40.4, 41.9, 44.7, 47.1, 48.8, 50.8, 52.7, and 55.9 ml, respectively. For the sample from selenium-deficient rats, lanes 1-19 corresponded to elution volumes of 15.9, 17.1, 18.3, 19.5, 21.9, 24.3, 26.7, 29.3, 30.5, 31.5, 33.8, 36.5, 38.5, 40.2, 42.8, 44.3, 45.6, 46.8, and 47.9 ml, respectively. TrxR in the fractions was detected by Western blotting.

Identification of protein bands

The protein identifications were performed according to an Agilent protein in-gel tryptic digestion kit (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA); a Voyager De-PRO MALDI mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at the Protein Analysis Center of Karolinska Institute was used to measure the peptide mass. The protein was identified by searching in the MS-fit of ProteinProspector with the peptide-mass fingerprinting data (http://prospector.ucsf.edu).

Detection of Sec with biotin-conjugated iodoacetamide (BIAM)

The liver homogenates (7 g) from selenium-deficient and control rats were dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5. Then the samples were loaded to a 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose column. After washing the column with 5 vol of TE buffer containing 50 mM NaCl, the bound proteins were eluted with 0.5 M NaCl in TE buffer. TrxR levels in the eluted samples were detected by Western blotting against rat TrxR antibody. Then, the rat liver samples with same amount of TrxR were applied for the measurement of TrxR activity by DTNB reduction assay and Sec labeling (36). Sec was specifically alkylated by BIAM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) at low pH (37, 38). The rat liver samples (20 μl) were reduced by 200 μM NADPH and incubated with 20 μM BIAM at pH 6.5 for 15 min. Then, 50 mM iodoacetamide was added to stop the labeling. The biotin was detected by streptavidin conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Dako).

TrxR binding with PAO-Sepharose beads

The binding of TrxR with PAO-Sepharose beads was performed according to the procedures described before to purify full-length TrxR protein from the truncated form (39). Following 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose column separation, the samples (500 μl) were reduced by 0.5 mM DTT at 4°C for 1 h and incubated with 200 μl of PAO-Sepharose beads for 30 min at room temperature. Then, the unbinding part was separated via centrifugation. TrxR-binding PAO-Sepharose beads were washed with TE buffer, 10 and 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mM DTT, and eluted with 500 μl of 10 mM 2,3-dimercaptopropanesulfonate as the binding part. These samples (10 μl) were separated on a 12% Bis-Tris gel with MES running buffer, and TrxR was detected by Western blotting.

C-terminal protein sequence analysis and measurement of peptide mass spectra of the trypsin digested TrxR

The purification of rat TrxR was as described previously (10), with some modifications. In brief, the 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose column-purified samples were dialyzed against TE buffer, applied to a DEAE-Sephacel anion exchange column (1.1×14 cm), and eluted with a gradient of 0 to 0.5 M NaCl in TE buffer. The fractions with TrxR activity were pooled, dialyzed, and purified further by an ω-amino-hexyl agarose column (1 ml). TrxR was eluted by a gradient of 0 to 0.5 M NaCl in TE buffer. Afterward, the fractions were separated on a 12% Bis-Tris gel with MOPS running buffer. The purified protein from selenium-deprived rat liver was subjected to C-terminal protein sequence analysis at the Protein Analysis Center (PAC) of the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, Karolinska Institute (40). The purified TrxRs were concentrated and denatured by 6 M urea, and the samples were reduced by 10 mM DTT and alkylated with 30 mM of iodoacetamide. The proteins were digested by trypsin at 37°C for 6 h and used for analysis by MALDI-MS at PAC.

RESULTS

Effects of selenium deficiency on the Trx and Grx systems of rat tissues

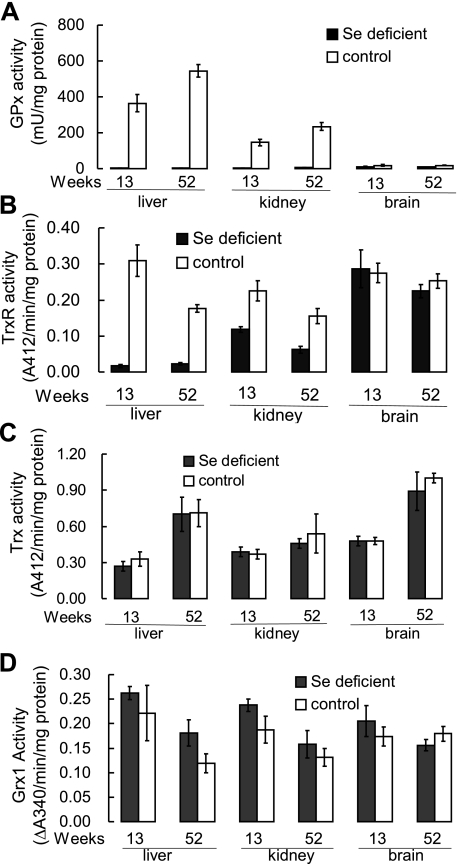

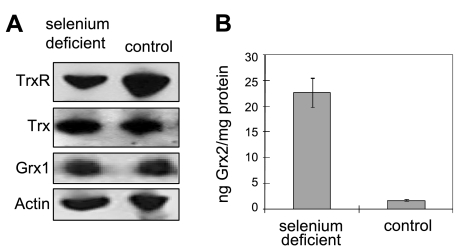

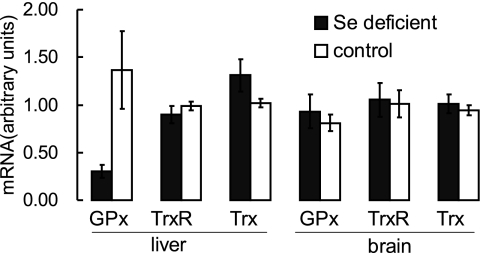

Rats fed the selenium-deficient diet for 13 and 52 wk developed severe selenium deficiency, as judged by plasma GPx activity and selenoprotein P concentration. Plasma GPx activity decreased to 1.1% of that in control rats at 13 wk. Selenoprotein P concentration was 6.5% of control at 13 wk and decreased further to 3.9% at 52 wk (41). The two main selenoproteins, TrxR and GPx in liver and kidney, were also reduced, and liver GPx activity in selenium-deficient rats was <1% of that in control rats at 13 wk (Fig. 1A, B). The brain is the most difficult tissue to deplete of selenium (42). At 13 wk, brain GPx activity was 61% of control, and at 52 wk, it was 50% of control. TrxR activity was reduced in selenium-deficient liver to 11% of that in control liver at 13 wk but did not decline further at 52 wk. Kidney TrxR activity was ∼50% of control at 13 wk and 40% of control at 52 wk. Selenium deficiency had little effect on brain TrxR activity either at 13 or 52 wk. These results are consistent with previous reports about the effects of selenium deficiency on selenoprotein levels (15, 43). Selenium deficiency did not induce a large change in the Trx and Grx1 contents in liver, kidney, or brain (Fig. 1C, D). The in vitro activity assays of Trx and Grx1 were consistent with the protein level measurements (Fig. 2A), and, more interestingly, the Grx2 level in the liver of selenium-deficient rats dramatically increased to 13-fold of that in control rats (Fig. 2B). Moreover, GPx1 mRNA was greatly decreased in liver by selenium deficiency, as expected (31), but it was not decreased in brain tissue (Fig. 3). Particularly, TrxR1 mRNA was not affected by selenium deficiency in liver or brain. Trx1 mRNA was increased in selenium-deficient liver compared with control liver, but was similar in brain tissue of both dietary groups (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

Effects of selenium deficiency on activities of Trx and Grx systems of cytosolic fraction of rat tissues. A) GPx activity. B) TrxR activity. C) Trx activity. D) Grx1 activity. Homogenates of liver, kidney, and brain were prepared from rats fed a selenium-deficient or control diet for 13 and 52 wk. TrxR and Trx activities were measured by insulin-dependent reduction assay. GR activity was measured by HED assay. Hydrogen peroxide was used as substrate for GPx activity. Data represent average of 4 experiments; error bars = sd.

Figure 2.

Effects of selenium deficiency on expression level of rat liver TrxR, Trx, Grx1, and Grx2. A) Western blotting of rat liver TrxR, Trx, Grx1, and actin. Liver homogenates from selenium-deficient and control rats were separated on a 12% Bis-Tris gel. Actin was used as loading control. B) Levels of Grx2 of liver extract from control and selenium-deficient rats were measured by ELISA with affinity-purified biotinylated human Grx2 antibodies.

Figure 3.

mRNA contents of GPx, TrxR, and Trx in liver and brain tissue from selenium-deficient and control rats. Results are expressed in arbitrary units determined by Northern blot analysis. Values are means ± sd[scap];n = 4.

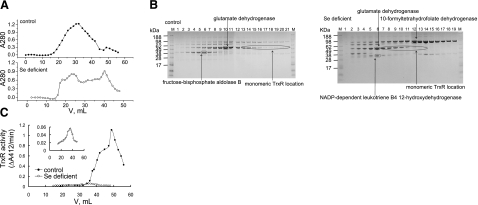

Expression pattern of flavoproteins binding to 2′,5′-ADP-Sepharose

The level of TrxR1 mRNA was not changed in any tissue, but the sharp decrease in TrxR activity in selenium-deficient tissue (Figs. 1B and 3) prompted us to investigate the nature of TrxR in selenium-deficient liver. We used a 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose affinity column, which can specifically bind NADPH-dependent enzymes, to enrich and purify TrxR from liver homogenates. The bound proteins were eluted with a gradient from 0 to 0.5 M NaCl. As shown in Fig. 4, the chromatographic profiles for the liver samples from selenium-deficient and control rats were different (Fig. 4A). A 55-kDa protein band was the most predominant protein bound to the 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose column in control samples, whereas in the selenium-deficient liver sample, a 97-kDa protein increased to be most abundant (Fig. 4B). Further in-gel digestion and MALDI-MS experiments identified the 97- and 55-kDa bands as 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase and glutamate dehydrogenase, respectively. The other main proteins at 37 and 39 kDa, expression levels affected by selenium deficiency, were identified as NADP-dependent leukotriene B4 12-hydroxydehydrogenase (LTB4 12-HD) and fructose-biphosphate aldose B (Fig. 4B). This result suggests that selenium deficiency induces changes in the cellular folate, glucose, and lipid metabolism (44, 45).

Figure 4.

Separation of liver extracts by 2′,5′-ADP-Sepharose chromatography. A) Chromatograms of liver homogenates from control rats (top panel) and selenium-deficient rats (bottom panel). Liver homogenates from selenium-deficient and control rats were applied to 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose columns. After washing, bound proteins were eluted with a gradient of NaCl. Protein concentration was monitored by absorbance at 280 nm. B) Detection of fractions with SDS-PAGE by Coomassie blue staining. Elution volumes corresponding to lanes are described in Materials and Methods. Identity of boxed bands was revealed after in-gel digestion and mass spectra analysis. Location of TrxR was identified by Western blotting. C) TrxR activity of purified fractions of liver homogenates from control rats (solid circles) or selenium-deficient rats (open circles). Insert: scale-enlarged figure for TrxR activity from selenium-deficient rats. TrxR activity was measured by DTNB reduction assay.

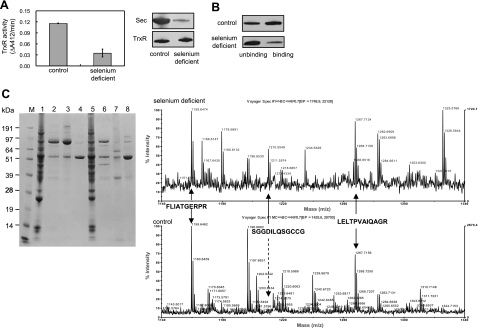

Existence of a low-activity TrxR in selenium-deficient rat liver

TrxR activity and protein in the fractions after 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose column purification were detected with DTNB reduction and Western blotting. The activity peak of TrxR from the selenium-deficient rat liver was much lower than that from the control rat liver (Fig. 4C). When two samples having the same amount of TrxR protein were compared for TrxR activity, the control showed much higher activity than that from selenium-deficient rat liver (Fig. 5A). This result suggested that some inactive or low-activity form of TrxR is present in the selenium-deficient liver sample. This result was confirmed by Sec-specific labeling and PAO-Sepharose binding experiments. We used a technique with BIAM coupled with streptavidin-HRP to detect the Sec content in the proteins (38). With similar levels of TrxR protein detected by Western blotting with TrxR antibodies, protein from control rat liver was shown to contain much more Sec than that from selenium-deficient rat liver (Fig. 5A). Next, the pooled proteins purified by 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose column were applied to a PAO-Sepharose bead column for binding under conditions that have been used to purify recombinant full-length active TrxR, which binds much more strongly than truncated TrxR lacking the two C-terminal amino acid residues (46). Most of the TrxR from control rat liver was bound with PAO-Sepharose beads, whereas only a small amount of bound TrxR from the selenium deficient rat liver was detected (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Existence of a low-activity TrxR in selenium-deficient rat liver. A) Liver homogenates from selenium-deficient and control rats were loaded on a 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose column. After washing, bound proteins were eluted with 0.5 M NaCl in TE buffer. TrxR activity in rat liver samples with same amount of TrxR was measured by DTNB reduction assay. Data represent average of 3 experiments; error bars = sd. Sec levels were labeled by BIAM at pH 6.5. TrxR level was detected by Western blotting. B) Comparison of TrxR binding with PAO-Sepharose beads. Following 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose column separation, DTT-reduced TrxRs were incubated with PAO-Sepharose beads. Unbinding part was obtained by centrifugation. Binding part was eluted by 2,3-dimercaptopropanesulfonate. After separation on a 12% Bis-Tris gel, TrxR in these samples was detected by Western blotting. C) TrxR purification and trypsin-digested peptide mass spectra of protein samples from selenium-deficient and control rat liver. Rat TrxRs were purified with a 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose column, a DEAE-Sephacel anion exchange column, and an ω-amino-hexyl agarose column. M, marker. Lanes 1–4, samples from selenium-deficient rat liver. Lanes 5–8, samples from control rat liver. Lanes 1 and 5, liver homogenates; lanes 2 and 6, factions after 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose column separation; lanes 3 and 7, fractions after a further DEAE-Sephacel anion exchange column separation; lanes 4 and 8, fractions after a further ω-amino-hexyl agarose column purification. Purified proteins were digested by trypsin and analyzed by MALDI-MS. Top spectrum: purified TrxR from selenium-deficient rat liver. Bottom spectrum: purified TrxR from control rat liver.

Identification of Sec residue replaced by cysteine in TrxR from selenium-deficient rat liver

To detect the exact form of this low-activity TrxR, we further purified the 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose column-enriched samples by DEAE-Sephacel anion exchange and ω-amino-hexyl agarose columns (Fig. 5C). The purified protein from the selenium-deprived rat livers was subjected to C-terminal sequencing, and the result showed that that the last amino acid residue was glycine, which indicated that the protein was full-length TrxR and not the truncated form. However, since the protein level was decreased by selenium depletion, our TrxR amount was not enough to detect the penultimate amino acid residue. The purified proteins were also analyzed by peptide mass spectrometry. Even after separation by 2′,5′-ADP Sepharose and DEAE-Sephacel anion exchange columns, the contents of TrxR in the enriched sample were still very low; in the trypsin-digested peptide mass spectra of the sample from selenium-deficient rat liver, no peak assigned to TrxR peptide could be found (data not shown). Most of the peptide mass could be assigned to other flavoproteins, such as glutamate dehydrogenase. However, further ω-amino-hexyl agarose column purification removed large amounts of glutamate dehydrogenase, and many peaks could now be assigned to TrxR using peptide mass spectra (Fig. 5C, top right panel). A peak at 1210.5, which could be assigned to SGGDILQSGCCG, appeared coincidently with the TrxR typical peptide masses 1159.6 and 1267.7, which were assigned to FLIATGERPR and LELTPVAIQAGR fragments (Fig. 5C, top right panel). This result suggested that the Sec in the C-terminal active site was replaced by cysteine. Mass fits for other forms, such as a truncated form lacking UG, the last two amino acid residues, or the form in which Sec was replaced by serine, were not observed. In the mass spectra of the sample from control rat liver, TrxR typical peptide masses of 1159.6, 1170.6, and 1267.7 were detected, but not the mass 1210.5 (Fig. 5C, bottom right panel), which suggests that no cysteine variant of TrxR existed in the selenium-rich conditions.

DISCUSSION

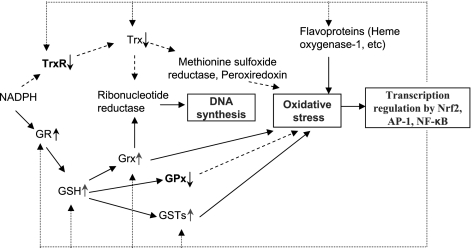

The Trx and the GSH-Grx systems are the two major thiol-dependent reductases that maintain a reducing intraenvironment in the presence of oxygen and with the protection of ROS. Trxs and Grxs catalyze the reduction of protein disulfides and specifically participate in DNA synthesis as electron donors of ribonucleotide reductase, or defense against oxidative stress as electron donors for peroxiredoxins (5, 8). TrxR is the only enzyme that can reduce oxidized Trx; thus. a decrease of cellular TrxR activity would result in reduction of electrons transferred from NADPH to Trx and change redox potential due to selenium deficiency. Because many of the functional roles of the Trx system in cells overlap with the GSH-Grx system (7), it is reasonable that the activity of GR, GSH, Grxs, and GSTs would increase (47,48,49) to keep up the flow of the electrons for DNA synthesis or defense against oxidative stress (Fig. 6). In particular, we found that mitochondrial Grx2, which plays critical roles against oxidative stress (50), increased 13-fold of the control. Since Grx2 is also a substrate of TrxR, this indicates that mitochondrial TrxR may be specifically critical in selenium starvation. Besides the components of the Trx and GSH systems, some flavoproteins regulated by Nrf-2, such as LTB4 12-HD, cytochrome P450 proteins, aldehyde dehydrogenase, and heme oxygenase-1, are overexpressed in selenium-deficient liver (47,48,49). A feedback regulation mechanism (Fig. 6) for Trx and GSH systems to maintain overall cellular redox status under the condition of selenium deficiency is proposed. Selenium deficiency causes a decrease of Trx system activity and induces oxidative stress. Subsequently, redox-sensitive transcription factors, such as Nrf-2, Ap-1, and NF-κB, will increase the mRNA level of Trx and GSH/Grx system enzymes and other antioxidants to achieve a new redox balance (51,52,53,54). Most recently, it has been reported that the elevation of many of the antioxidant enzymes caused by selenium deficiency is really mediated by Nrf-2 (51). This finding is consistent with the observation that Sec tRNA deletion caused induction of the Nrf-2-regulated genes (52).

Figure 6.

A feedback regulation mechanism for Trx and GSH-Grx systems under selenium-deficient conditions. Selenium deficiency will cause decrease in Trx system activity, which induces oxidative stress. Subsequently, redox-sensitive transcription factors, such as Nrf-2, NF-κB and AP-1, will respond and increase the mRNA level of Trx and GSH systems and other antioxidants to achieve a new redox balance. Dashed line indicates decrease of protein activity or amount. Solid line indicates increase of protein activity or amount. Dotted line indicates that proteins are regulated by redox-sensitive transcription factors.

Some animal models have shown that supplemental selenium has the beneficial effect of reducing the incidence of cancer (2). However, selenium deficiency was also shown to inhibit hepatocarcinogenesis in transgenic mice (48), and recently TrxR emerged as a molecular target for cancer therapy because it is overexpressed in many cancer cells and is critical for proliferation in vivo (18). The dramatic decrease of TrxR activity observed may provide a reasonable explanation for hepatocarcinogenesis inhibition by selenium deficiency (48) since the high efficiency for transfer of electrons to, e.g., ribonucleotide reductase and DNA synthesis via Sec-containing TrxR should be sharply decreased.

Some selenoproteins and their Cys homologues have been found to coexist in the same eukaryote (55). In human and rats, selenoproteins GPx and selenophosphate synthetase have Cys homologues (55). For high-molecular-weight or large TrxRs, many Cys homologs have been found in eukaryotes. The mitochondrial TrxR2 possesses a GCCG motif, and cytosolic TrxR 1 has a GCUG motif in Caenorhabditis elegans (56). No gene corresponding to a Cys homologue exists in rat and human genomes; therefore, it is remarkable to find the change of Sec by Cys for mammalian TrxR under selenium-starvation conditions. This change may occur via some unique mechanisms, such as the misreading of the UGA codon as cysteine by UGA suppression, which has been observed in rabbit reticulocyte lysates in vitro and in vivo (57, 58). UGA decoded as cysteine has also been reported in other biological systems, such as in E. coli (59, 60) and in pheromone 3 of Euplotes octocarinatus (61). One possibility why Sec residue was replaced by cysteine in TrxR under selenium deprivation may be that O-P-seryl-tRNASec is converted to Cys-tRNASec, which decodes the UGA with cysteine.

The observation we have made that a cysteine-variant TrxR exists in selenium-deficient rat liver is consistent with the results that selenium supplementation dramatically increases TrxR-specific activity, whereas the protein level is only slightly increased in cell culture and animal models (43, 62). Although the GSH-Grx system provides a compensatory effect to the loss of the Trx activity, the fact that the truncated enzyme is not made (since it is toxic; ref. 21) and high mRNA, present during selenium starvation, may indicate the importance of the active TrxR in selenium metabolism. Most recently TrxR has been revealed to be essential for the reduction of selenium compounds such as selenite to selenide for selenoprotein synthesis (2, 63). The mutant TrxR, in which Sec is replaced by Cys, possesses activity to reduce Trx with ∼10% catalytic efficiency compared with that of wild-type TrxR (14, 38) and gives the cell the potential to recover the process of selenoprotein synthesis in the event of selenium replenishment.

We demonstrate here that the loss of selenoprotein activity by selenium deficiency induced a cellular overall redox proteome change in rat liver, including folate, glucose, and lipid metabolism enzyme alterations. Under conditions of severe selenium deficiency, a UGA misreading occurs, producing a low-activity non-selenium-containing form of TrxR. In addition, the dramatic decrease of electron transfer by the Trx pathway was compensated by an increase of the GSH-Grx pathway, since the blockage of both pathways causes cell death (7), and the alterations may be effected through the regulation of the redox-related transcription factors Nrf-2 and NF-κB.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Elias Arnér and Mr. Qing Cheng (Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, Karolinska Institute) for kindly providing PAO Sepharose beads; R. Eliasson for the preparation of anti-rat TrxR antibodies; and Amy K. Motley and Marjan Hessam Amiri for technical assistance. This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society (grant 961), the Swedish Research Council (grant 3529), the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grant ES02497), and the K. A. Wallenberg foundation. L.Z. was supported in part by a fellowship from the Swedish Hagelén Foundation.

References

- Kryukov G V, Castellano S, Novoselov S V, Lobanov A V, Zehtab O, Guigo R, Gladyshev V N. Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes. Science. 2003;300:1439–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.1083516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp L V, Lu J, Holmgren A, Khanna K K. From selenium to selenoproteins: synthesis, identity, and their role in human health. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:775–806. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Holmgren A. Selenoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:723–727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S G, Chae H Z, Kim K. Peroxiredoxins: a historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:1543–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren A. Thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13963–13966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren A. Thioredoxin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:237–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Chew E H, Holmgren A. Targeting thioredoxin reductase is a basis for cancer therapy by arsenic trioxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12288–12293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701549104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnér E S, Holmgren A. Physiological functions of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6102–6109. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillig C H, Holmgren A. Thioredoxin and related molecules-from biology to health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:25–47. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.9.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthman M, Holmgren A. Rat liver thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase: purification and characterization. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6628–6633. doi: 10.1021/bi00269a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladyshev V N, Jeang K T, Stadtman T C. Selenocysteine, identified as the penultimate C-terminal residue in human T-cell thioredoxin reductase, corresponds to TGA in the human placental gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6146–6151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L, Arnér E S, Holmgren A. Structure and mechanism of mammalian thioredoxin reductase: the active site is a redox-active selenolthiol/selenenylsulfide formed from the conserved cysteine-selenocysteine sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5854–5859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100114897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandalova T, Zhong L, Lindqvist Y, Holmgren A, Schneider G. Three-dimensional structure of a mammalian thioredoxin reductase: implications for mechanism and evolution of a selenocysteine-dependent enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9533–9538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171178698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L, Holmgren A. Essential role of selenium in the catalytic activities of mammalian thioredoxin reductase revealed by characterization of recombinant enzymes with selenocysteine mutations. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18121–18128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000690200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill K E, McCollum G W, Boeglin M E, Burk R F. Thioredoxin reductase activity is decreased by selenium deficiency. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234:293–295. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupoglu C, Przemeck G K, Schneider M, Moreno S G, Mayr N, Hatzopoulos A K, de Angelis M H, Wurst W, Bornkamm G W, Brielmeier M, Conrad M. Cytoplasmic thioredoxin reductase is essential for embryogenesis but dispensable for cardiac development. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1980–1988. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.5.1980-1988.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad M, Jakupoglu C, Moreno S G, Lippl S, Banjac A, Schneider M, Beck H, Hatzopoulos A K, Just U, Sinowatz F, Schmahl W, Chien K R, Wurst W, Bornkamm G W, Brielmeier M. Essential role for mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase in hematopoiesis, heart development, and heart function. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9414–9423. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9414-9423.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urig S, Becker K. On the potential of thioredoxin reductase inhibitors for cancer therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:452–465. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnér E S, Holmgren A. The thioredoxin system in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnér E S, Sarioglu H, Lottspeich F, Holmgren A, Bock A. High-level expression in Escherichia coli of selenocysteine-containing rat thioredoxin reductase utilizing gene fusions with engineered bacterial-type SECIS elements and co-expression with the selA, selB and selC genes. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:1003–1016. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestal K, Arner E S. Rapid induction of cell death by selenium-compromised thioredoxin reductase 1 but not by the fully active enzyme containing selenocysteine. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15966–15972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210733200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L, Arnér E S, Ljung J, Aslund F, Holmgren A. Rat and calf thioredoxin reductase are homologous to glutathione reductase with a carboxyl-terminal elongation containing a conserved catalytically active penultimate selenocysteine residue. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8581–8591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozell B, Hansson H A, Luthman M, Holmgren A. Immunohistochemical localization of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase in adult rats. Eur J Cell Biol. 1985;38:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burk R F. Production of selenium deficiency in the rat. Methods Enzymol. 1987;143:307–313. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)43058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren A, Bjornstedt M. Thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Methods Enzymol. 1995;252:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)52023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnér E S, Zhong L, Holmgren A. Preparation and assay of mammalian thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Methods Enzymol. 1999;300:226–239. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)00129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren A. Glutathione-dependent synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides. Characterization of the enzymatic mechanism of Escherichia coli glutaredoxin. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:3672–3678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren A, Aslund F. Glutaredoxin. Methods Enzymol. 1995;252:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)52031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence R A, Burk R F. Glutathione peroxidase activity in selenium-deficient rat liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;71:952–958. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90747-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg M, Fernandes A P, Kumar S, Holmgren A. Cellular and plasma levels of human glutaredoxin 1 and 2 detected by sensitive ELISA systems. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319:801–809. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill K E, Lyons P R, Burk R F. Differential regulation of rat liver selenoprotein mRNAs in selenium deficiency. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;185:260–263. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80984-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savonet V, Maenhaut C, Miot F, Pirson I. Pitfalls in the use of several “housekeeping” genes as standards for quantitation of mRNA: the example of thyroid cells. Anal Biochem. 1997;247:165–167. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill K E, Lloyd R S, Yang J G, Read R, Burk R F. The cDNA for rat selenoprotein P contains 10 TGA codons in the open reading frame. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:10050–10053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X, Bjornstedt M, Shen B, Ericson M L, Holmgren A. Mutagenesis of structural half-cystine residues in human thioredoxin and effects on the regulation of activity by selenodiglutathione. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9701–9708. doi: 10.1021/bi00088a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla C A, Martinez-Galisteo E, Barcena J A, Spyrou G, Holmgren A. Purification from placenta, amino acid sequence, structure comparisons and cDNA cloning of human glutaredoxin. Eur J Biochem. 1995;227:27–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew E H, Lu J, Bradshaw T D, Holmgren A. Thioredoxin reductase inhibition by antitumor quinols: a quinol pharmacophore effect correlating to antiproliferative activity. FASEB J. 2008;22:2072–2083. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-101477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Papp L V, Fang J, Rodriguez-Nieto S, Zhivotovsky B, Holmgren A. Inhibition of mammalian thioredoxin reductase by some flavonoids: implications for myricetin and quercetin anticancer activity. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4410–4418. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S R, Bar-Noy S, Kwon J, Levine R L, Stadtman T C, Rhee S G. Mammalian thioredoxin reductase: oxidation of the C-terminal cysteine/selenocysteine active site forms a thioselenide, and replacement of selenium with sulfur markedly reduces catalytic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2521–2526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050579797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Q, Stone-Elander S, Arner E S. Tagging recombinant proteins with a Sel-tag for purification, labeling with electrophilic compounds or radiolabeling with 11C. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:604–613. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman T, Cederlund E, Jornvall H. Chemical C-terminal protein sequence analysis: improved sensitivity, length of degradation, proline passage, and combination with edman degradation. Anal Biochem. 2001;290:74–82. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J G, Hill K E, Burk R F. Dietary selenium intake controls rat plasma selenoprotein P concentration. J Nutr. 1989;119:1010–1012. doi: 10.1093/jn/119.7.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigelius-Flohe R. Tissue-specific functions of individual glutathione peroxidases. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:951–965. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berggren M M, Mangin J F, Gasdaska J R, Powis G. Effect of selenium on rat thioredoxin reductase activity. Increase by supranutritional selenium and decrease by selenium deficiency. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:187–193. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh J R, Herbig A K, Stover P J. New perspectives on folate catabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:255–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primiano T, Li Y, Kensler T W, Trush M A, Sutter T R. Identification of dithiolethione-inducible gene-1 as a leukotriene B4 12-hydroxydehydrogenase: implications for chemoprevention. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:999–1005. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.6.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson L, Chen C, Thorell J O, Fredriksson A, Stone-Elander S, Gafvelin G, Arner E S. Exploiting the 21st amino acid-purifying and labeling proteins by selenolate targeting. Nat Methods. 2004;1:61–66. doi: 10.1038/nmeth707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter R, Wendel A. Selenium and drug metabolism–I. Multiple modulations of mouse liver enzymes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1983;32:3063–3067. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoselov S V, Calvisi D F, Labunskyy V M, Factor V M, Carlson B A, Fomenko D E, Moustafa M E, Hatfield D L, Gladyshev V N. Selenoprotein deficiency and high levels of selenium compounds can effectively inhibit hepatocarcinogenesis in transgenic mice. Oncogene. 2005;24:8003–8011. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostert V, Hill K E, Burk R F. Loss of activity of the selenoenzyme thioredoxin reductase causes induction of hepatic heme oxygenase-1. FEBS Lett. 2003;541:85–88. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00309-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillig C H, Lonn M E, Enoksson M, Fernandes A P, Holmgren A. Short interfering RNA-mediated silencing of glutaredoxin 2 increases the sensitivity of HeLa cells toward doxorubicin and phenylarsine oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13227–13232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401896101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burk R F, Hill K E, Nakayama A, Mostert V, Levander X A, Motley A K, Johnson D A, Johnson J A, Freeman M L, Austin L M. Selenium deficiency activates mouse liver Nrf2-ARE but vitamin E deficiency does not. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1617–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Kelly V P, Motohashi H, Nakajima O, Takahashi S, Nishimura S, Yamamoto M. Deletion of the selenocysteine tRNA gene in macrophages and liver results in compensatory gene induction of cytoprotective enzymes by Nrf2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2021–2030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalini S, Bansal M P. Alterations in selenium status influences reproductive potential of male mice by modulation of transcription factor NFkappaB. Biometals. 2007;20:49–59. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu K S, Zamamiri-Davis F, Stewart J B, Thompson J T, Sordillo L M, Reddy C C. Selenium deficiency increases the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in RAW 264.7 macrophages: role of nuclear factor-kappaB in up-regulation. Biochem J. 2002;366:203–209. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano S, Lobanov A V, Chapple C, Novoselov S V, Albrecht M, Hua D, Lescure A, Lengauer T, Krol A, Gladyshev V N, Guigo R. Diversity and functional plasticity of eukaryotic selenoproteins: identification and characterization of the SelJ family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16188–16193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505146102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey B M, Hondal R J. Characterization of mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase from C. elegans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;346:629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y X, Copeland T D, Oroszlan S, Rein A, Levin J G. Identification of amino acids inserted during suppression of UAA and UGA termination codons at the gag-pol junction of Moloney murine leukemia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:8860–8863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.22.8860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittum H S, Lane W S, Carlson B A, Roller P P, Lung F D, Lee B J, Hatfield D L. Rabbit beta-globin is extended beyond its UGA stop codon by multiple suppressions and translational reading gaps. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10866–10870. doi: 10.1021/bi981042r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron C, Heider J, Bock A. Mutagenesis of selC, the gene for the selenocysteine-inserting tRNA-species in E. coli: effects on in vivo function. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6761–6766. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.23.6761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban C, Beier H. Cysteine tRNAs of plant origin as novel UGA suppressors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4591–4597. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.22.4591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer F, Schmidt H J, Plumper E, Hasilik A, Mersmann G, Meyer H E, Engstrom A, Heckmann K. UGA is translated as cysteine in pheromone 3 of Euplotes octocarinatus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:3758–3761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustacich D, Powis G. Thioredoxin reductase. Biochem J. 2000;346:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahata M, Tamura T, Abe K, Mihara H, Kurokawa S, Yamamoto Y, Nakano R, Esaki N, Inagaki K. Selenite assimilation into formate dehydrogenase H depends on thioredoxin reductase in Escherichia coli. J Biochem. 2008;143:467–473. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]