Abstract

Duchenne-Meryon muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the most common and lethal genetic muscle disease. Ameliorating muscle necrosis, inflammation, and fibrosis represents an important therapeutic approach for DMD. Imatinib, an antineoplastic agent, demonstrated antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effects in liver, kidney, lung, and skin of various animal models. This study tested antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effects of imatinib in mdx mice, a DMD mouse model. We treated mdx mice with intraperitoneal injections of imatinib at the peak of limb muscle inflammation and the onset of diaphragm fibrosis. Controls received PBS vehicle or were left untreated. Muscle necrosis, inflammation, fibrosis, and function were evaluated by measuring serum CK activity, endomysial CD45 immunoreactive inflammation area, endomysial collagen III deposition, and hind limb grip strength. Phosphorylation of the tyrosine kinase targets of imatinib was assessed by Western blot in diaphragm tissue and in primary cultures of peritoneal macrophages and skeletal muscle fibroblasts. Imatinib markedly reduced muscle necrosis, inflammation, and fibrosis, and significantly improved hind limb grip strength in mdx mice. Reduced clinical disease was accompanied by inhibition of c-abl and PDGFR phosphorylation and suppression of TNF-α and IL-1β expression. Imatinib therapy for DMD may hold promise for ameliorating muscle necrosis, inflammation, and fibrosis by inhibiting c-abl and PDGFR signaling pathways and downstream inflammatory cytokine and fibrotic gene expression.—Huang, P., Zhao, X. S., Fields, M., Ransohoff, R. M., Zhou, L. Imatinib attenuates skeletal muscle dystrophy in mdx mice.

Keywords: necrosis, inflammation, fibrosis, c-abl, TGF-β, PDGF

DMD is the most common genetic muscle disease, affecting 1 in 3500 live male births (1). Caused by a defective dystrophin gene on the X chromosome, DMD is characterized by progressive skeletal and cardiac muscle weakness with premature death (2). Muscle necrosis, inflammation, and fibrosis are prominent pathological features of DMD. These pathological changes lead to muscle dysfunction and clinical weakness. Therefore, ameliorating these pathological changes represents an important therapeutic approach to improve muscle function and DMD phenotype.

Currently no effective therapy for DMD exists. Gene therapy and cell therapy to replace the missing dystrophin gene are promising but not yet applicable. The only relatively effective pharmacotherapy for DMD is corticosteroids, which offer modest benefit by prolonging independent ambulation by 2–4 yr but carry a troublesome side effect profile. Although prednisone was evaluated initially to suppress muscle inflammation, its therapeutic mechanism in DMD is still not entirely clear. At this point, no effective pharmacotherapy can attenuate muscle necrosis or fibrosis in patients with DMD.

Imatinib selectively and competitively blocks the ATP binding sites of several tyrosine kinases, including c-abl, c-kit, and platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFRs) (3). Imatinib has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) by blocking bcr-abl (Philadelphia chromosome) activity; gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) by blocking c-kit activity; and a number of other malignancies by blocking c-kit and PDGFR activity. The PDGF signaling pathway has been implicated in regulating organ fibrosis and inflammation (4). Recent studies have shown that c-abl signaling pathway mediates the fibrogenic effect of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) (5, 6). TGF-β is a potent profibrotic cytokine that plays an important role in driving tissue fibrosis. Although TGF-β signaling transduction usually involves its downstream Smad proteins, its fibrogenic effect mediated by c-abl is independent of Smad. So the c-abl signaling pathway represents an alternative non-Smad pathway of TGF-β (5, 6). The c-abl kinase activity can also be activated by PDGFR activation (5, 6). Imatinib markedly reduced bone marrow fibrosis in CML, independent of the cytogenic response (7). These findings suggest that imatinib holds potential for treating human fibrotic disorders by inhibiting PDGF and c-abl mediated non-Smad TGF-β pathways. Therefore, imatinib is not only a revolutionary targeted antineoplastic therapy but also a promising antiinflammatory and antifibrotic therapy. Its antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effects have been demonstrated by animal studies. Imatinib ameliorated glomerulonephritis in the murine lupus models, MRL/lpr and NZB/W mice (8, 9). Imatinib also attenuated lymphadenopathy and salivary gland inflammation associated with lupus in MRL/lpr mice (8, 9). Imatinib inhibited LPS-induced TNF-dependent acute hepatitis in mice and significantly improved survival (10). Imatinib substantially inhibited renal fibrosis in rats induced by unilateral ureter obstruction (6), pulmonary fibrosis in mice induced by bleomycin (5) or radiation (11), liver fibrosis in rats induced by pig serum (12), and skin fibrosis in mice induced by bleomycin (13). Imatinib ablated induction of proliferation and extracellular matrix gene expression of renal and pulmonary fibroblasts by TGF-β and PDGF (5, 6). These in vivo and in vitro findings collectively suggest that imatinib can inhibit growth factor-dependent fibrogenic pathways in multiple tissues. Therefore, we hypothesized that imatinib could inhibit muscle inflammation and fibrosis associated with DMD.

Mdx mice, which harbor a nonsense mutation in exon 23 of the dystrophin gene, have been widely used for studying pathophysiology and for testing potential therapies for DMD. Based on the studies published by our lab and others, skeletal muscle inflammation in mdx mice starts at 3 wk of age, peaks at 8–16 wk of age, and then spontaneously subsides in limb muscles but not diaphragm (14,15,16,17). Slowly progressive endomysial fibrosis develops only in diaphragm, which becomes morphologically evident from 12 wk of age (17,18,19). To test our hypothesis, we treated mdx mice with imatinib from 8 to 14 wk, corresponding to the peak of limb muscle inflammation and the onset of diaphragm fibrosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and imatinib treatment

Fifteen male mdx mice (C57BL/10ScSn-Dmdmdx/J) and 5 male wild-type mice (C57BL/10ScSn) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). These mice were divided into 4 groups: 1) 5 mdx mice were treated with daily intraperitoneal injection of imatinib (50 mg/kg/d, purchased from the Cleveland Clinic pharmacy) from 8 to 14 wk; 2) 5 mdx mice were treated with daily injections of the same volume of PBS vehicle; 3) 5 mdx mice were untreated; and 4) 5 wild-type mice were untreated. These mice were sacrificed at 14 wk of age. Quadriceps and diaphragm muscles were collected for histopathological, immunohistochemical, RNA, and protein analyses. Blood samples were collected for measuring serum creatine kinase (CK) activity. We followed the guide for the care and use of laboratory animals of Cleveland Clinic. Six weeks after interventions (at age 14 wk), mdx mice in the imatinib group, but not the PBS or untreated groups, displayed weight loss, and the body weight (g) was 24.2 ± 3.1 in the imatinib group, 31.0 ± 2.5 (P<0.001) in the PBS group, and 31.3 ± 1.7 (P<0.001) in the untreated group. The weight loss was most likely due to chemical-induced chronic peritonitis from daily intraperitoneal injection of imatinib. This side effect was reported in other studies using intraperitoneal injection (6) but not oral gavage (8, 9) of imatinib. Dissection of our imatinib-treated mice did reveal intestinal adhesions, presumably from peritonitis.

Histopathological analysis

Muscle tissue was fresh-frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane, sectioned at 8 μm, stained with hematoxylin, and viewed under a bright field microscope.

CK measurements

Serum CK activity was measured using the CK detection kit (Teco Diagnostics, CA, USA), following the instructions provided by the manufacturer.

Immunostaining

Cryostat sections (8 μm) of fresh frozen muscle tissue were blocked in 5% normal rabbit (for CD45 immunostaining) or donkey (for collagen III immunostaining) serum at room temperature for 1 h followed by incubation in primary antibodies against mouse CD45 (Serotec, Oxford, UK) and collagen III (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL, USA) overnight at 4°C. For CD45 immunostaining, the sections were then incubated in biotinylated secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) at room temperature for 1 h followed by incubation with ABC (Vector Laboratories) at room temperature for 30 min. Antibody binding was visualized with DAB substrate (Vector Laboratories) and viewed under a light microscope. For collagen III immunostaining, following the primary antibody incubation, the sections were incubated in FITC-conjugated donkey anti-goat secondary antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) at room temperature for 1 h. Antibody binding was visualized under a fluorescent microscope.

Quantification of inflammation

Quantitative analysis of inflammation was performed by determining CD45 immunoreactivity as described previously (20, 21). CD45 stains all leukocytes. CD45 immunoreactivity, defined as area occupied by reaction product except for normal endomysial capillaries and expressed as a percentage of total muscle cross-section area, was calculated on digitized images using an integrated image analysis system attached to a microscope (Olympus BX41; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Serial sections were obtained from quadriceps and diaphragm muscles. Ten sections, representing one of every 5 sections, of each sample were used for CD45 immunostaining. Immunostained muscle sections, with each section containing 5 nonoverlapping fields of view, were digitized under an ×10 objective for quadriceps and an ×20 objective for diaphragm, using a 3-CCD color video camera interfaced with Sport Image analysis software. Digitized images were analyzed using the National Institutes of Health Image J1.34 software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). Establishing an area measurement analysis helped determine the proportion of immunoreactivity area within each fixed field of view. These parameters were then held constant for each set of images obtained at equal objectives and light sensitivities on slides, which were processed at one session. The data represented the mean area occupied by immunoreactivity and were expressed as a percentage of total quadriceps or diaphragm cross-section area.

Evaluation of endomysial fibrosis

Endomysial fibrosis of diaphragm was evaluated by collagen III immunostaining. Collagen III immunoreactive area was quantified using the same method as described above for quantifying CD45 immunoreactive area.

Hind limb grip strength measurements

Hind limb grip strength was measured in 4 groups of mice at age 8, 12, and 14 wk using an automated Grip Strength Meter (GSM, Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA). The Grip Strength Meter provides a validated measurement of motor function. The instrument uses an electronic digital force gauge that measures the peak force exerted on it by the action of the animal. For each time point, we measured grip strength 20 times in each individual mouse and repeated the measurements on a separate day within 3 d, and the average was used as the outcome value.

Western blot

Muscle tissue was homogenized in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% CHAPS, 10% glycerol, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1% aprotinin, and 1% leupeptin, supplemented with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail II (Sigma) and 1× phosphatase inhibitor cocktail II (Sigma). The tissue or primary cell culture lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 1000 g for 20 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined by a Bio-Rad protein assay. Together with the Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad), 50–80 μg total proteins (depending on different primary antibodies) were boiled for 5 min and subsequently separated by electrophoresis on 4–12% SDS-polyacrylamide Bis-Trisgels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Nonspecific protein binding was blocked by incubating the membranes in 1× PBS containing 5% nonfat milk plus 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) for 2 h at room temperature. The membrane was then incubated with the primary antibodies in buffer PBST containing 2% BSA at 4°C overnight. These antibodies included α-tubulin, c-abl, phosphorylated c-abl, PDGFR-α, phosphorylated PDGFR-α, PDGFR-β, phosphorylated PDGFR-β, Smad2, phosphorylated Smad2, TNF-α, IL-1β, and fibronectin. After incubation with appropriate HRP-labeled secondary antibody (1:5000 to 1:10,000) for 1 h at room temperature, the signals were detected by the ECL detection system (Amersham, Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ, USA) following the instructions of the manufactory. Densitometric analyses of Western blot signal bands were performed by using the TotalLab TL100 software (Nonlinear Dynamics Ltd, USS Inc., Durham, NC, USA).

RT-PCR

Muscle tissue was lysed using Trizol (Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD, USA), and total RNA was extracted following the manufacturer’s instructions. Use of RNase-free DNnase I (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) minimized the contamination with genomic DNA. We produced complementary DNA (cDNA) using the SuperScript TM II RT kit (Invitrogen) following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Quantitative PCR was performed using LightCycler (Roche) as described previously (22) and by using the following primers: TNF-α: upper: 5′-GGC AGGTCTACTTTGGAGTCATTG C-3′, lower: 5′-ACATTCGAGGCTCCAGTGAATTCGG-3′; IL-1β: upper: 5′- CCTTCTTTTCCTTCATCTTTG-3′, lower: 5′-ACCGCTTTTCCATCTTCTTCT-3′. Mouse GAPDH was used as an internal positive control. Reaction specificity was determined by product melting curves (allowing exclusion of primer dimer-contaminated or alternatively spliced products). The product size was verified by agarose gels.

In vitro primary cell cultures and treatments

Wild-type mouse peritoneal macrophages were harvested by peritoneal lavage 3–4 d after intraperitoneal injection of 4% sterile thioglycolate in the female C57BL/10ScSn mice, as described previously (23). Macrophages were cultured in PMRI 1640 containing 10% FBS for 24 h, incubated with or without (control) 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 (ProsPec Tany TechnoGene Ltd., Rehovot, Israel), 10 μg/ml imatinib, or both for 1 or 6 h. Cells treated with imatinib were preincubated with this compound for 45 min.

Primary skeletal muscle fibroblast culture was established by using the method previously described (24, 25). Briefly, mdx diaphragm muscles were collected, rinsed in DMEM/F-12 medium (plus 100 U/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/ml anfotericin B), minced into pieces smaller than 3 mm2, seeded into 3.8 cm2-well plates, and covered with 500 μl of DMEM/F-12 growth medium supplemented with 50% (v/v) fetal calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA). Explants were kept in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. Fresh growth medium (250 μl/well) was added the second day. Fibroblasts emigrated from muscle explants after 3–4 d. When fibroblasts covered 50–70% of the well surface, muscle explants were removed, and fibroblasts were cultured in the growth medium supplemented with 10% FCS. The third passage was used for the treatment with or without (control) 10 μg/ml imatinib for 24 h in addition to with or without the treatment with 40 ng/ml PDGF-BB (ProsPec Tany TechnoGene Ltd.) or 10 ng/ml TGF-β1.

Statistical analysis

Differences in measurements among different groups were first analyzed using analysis of variance, and differences between different groups were then compared using a contrast statement. Statistical software package SAS and the mixed procedure were used (SAS version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A value of P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Imatinib markedly reduced muscle necrosis and inflammation in mdx quadriceps and diaphragm

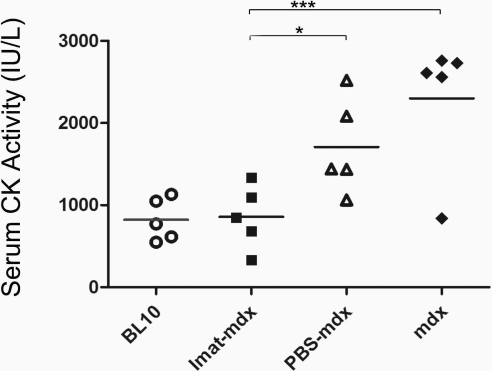

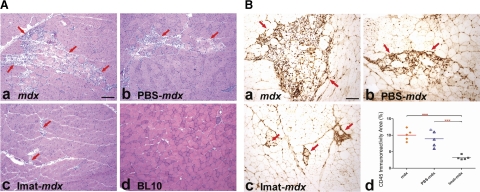

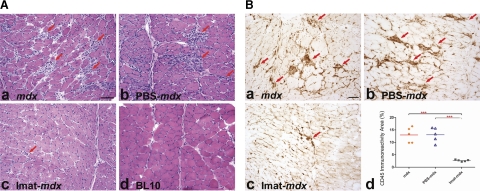

To address whether imatinib attenuated skeletal muscle necrosis and inflammation, we compared serum CK activity and endomysial CD45 immunoreactive area in quadriceps and diaphragm muscles of 4 groups of mice at 14 wk of age: 1) imatinib-treated mdx mice; 2) PBS (vehicle)-treated mdx mice; 3) untreated mdx mice; and 4) wild-type BL10 mice. Serum CK activity (IU/L) was markedly reduced and was near normal in mdx mice after imatinib treatment (mean±sd: 858.6±384.8) as compared with wild-type mice (822.8±258.7) and PBS-treated (1818.1±821.5, P=0.03) and untreated (2300.3±821.4, P<0.001) mdx mice (Fig. 1). These findings indicate that imatinib inhibited muscle necrosis and degeneration. Compared with untreated and PBS-treated mdx mice, the imatinib group showed substantial reduction of endomysial necrosis and inflammation in quadriceps (Fig. 2) and diaphragm (Fig. 3) by H&E stain (Figs. 2A and 3A) and highlighted by CD45 immunostaining (Figs. 2B and 3B). CD45 immunoreactive area (%) was significantly smaller in quadriceps of the imatinib-treated (3.2±0.6) than in those of the PBS-treated (8.9±2.5, P<0.001) and untreated (10.0±1.7, P<0.001) mdx groups (Fig. 2Bd). Likewise, CD45 immunoreactive inflammation area (%) was significantly reduced in diaphragm of the imatinib-treated mdx mice (2.7±0.4) as compared with the PBS-treated (13.1±2.9, P<0.001) and untreated (13.0±3.1, P<0.001) mdx mice (Fig. 3B–D). These findings demonstrated that imatinib significantly attenuated skeletal muscle inflammation associated with dystophin deficiency in mdx mice.

Figure 1.

Imatinib reduced serum CK in mdx mice. Bar graph shows a significant reduction and near normalization of serum CK activity in imatinib-treated mdx mice as compared with wild-type BL10 mice and PBS-treated and untreated mdx mice. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Imatinib reduced muscle necrosis and inflammation in mdx quadriceps. A) H&E staining of quadriceps showed striking smaller muscle necrosis and inflammation areas (arrows) in imatinib-treated mdx mice (c) as compared with untreated mdx (a) and PBS-treated mdx mice (b). Muscle necrosis and inflammation were absent in wild-type BL10 mice (d). B) CD45 immunostaining of quadriceps highlighted inflammation areas (arrows) in mdx (a), PBS- treated mdx (b), and imatinib-treated mdx mice (c). Percentage of CD45 immunoreactive inflammation areas was reduced markedly in imatinib-treated mdx mice as compared with PBS-treated and untreated mdx mice (d). Scale bars = 25 μm. ***P < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Imatinib reduced necrosis and inflammation in mdx diaphragm. A) H&E staining of diaphragm showed multiple small- and medium-sized endomysial inflammatory foci (arrows) in mdx (a) and PBS-treated mdx mice (b). In contrast, only a few small foci of inflammation (arrows) were seen in imatinib-treated mdx mice (c). Muscle necrosis and inflammation were absent in wild-type BL10 mice (d). B) CD45 immunostaining of diaphragm highlighted inflammation areas (arrows) in mdx (a), PBS-treated mdx (b), and imatinib-treated mdx mice (c). Percentage of CD45 immunoreactive inflammation area was reduced markedly in imatinib-treated mdx mice as compared with PBS-treated and untreated mdx mice (d). Scale bars = 25 μm. ***P < 0.001.

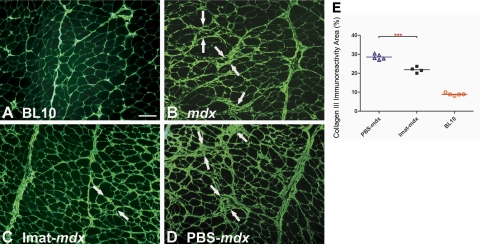

Imatinib attenuated mdx diaphragm fibrosis

Progressive endomysial fibrosis develops in diaphragm of mdx mice and becomes morphologically evident from 12 wk of age (17). We treated mdx mice with imatinib from 8 to 14 wk of age to address whether imatinib could inhibit the onset of diaphragm fibrosis. Collagen III immunostaining was used to assess diaphragm endomysial fibrosis. At 14 wk of age, endomysial collagen III deposition was notably increased in diaphragm of mdx mice (Fig. 4B) as compared with age-matched wild-type mice (Fig. 4A). The increase was attenuated markedly by imatinib (Fig. 4C) but not PBS treatment (Fig. 4D). Endomysial collagen III immunoreactive area (%) was significantly lower in diaphragm of the imatinib-treated mdx mice (21.9±1.5) than in the PBS-treated mdx mice (28.5±1.4, P<0.001, Fig. 4E). Imatinib attenuated early development of diaphragm fibrosis in mdx mice.

Figure 4.

Imatinib reduced mdx diaphragm fibrosis. Collagen III immunostaining of diaphragm showed increased endomysial collagen deposition (arrows) in mdx (B) and PBS-treated mdx (D) mice but much less so in imatinib-treated mdx mice (C), as compared with wild-type BL10 mice (A). Endomysial collagen III immunoreactivity area was reduced significantly in imatinib-treated mdx mice as compared with PBS-treated mdx mice (E). Scale bar = 25 μm. ***P < 0.001.

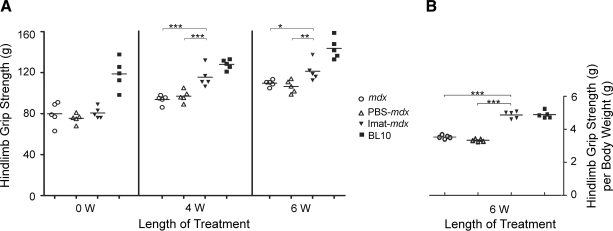

Imatinib improved hind limb grip strength in mdx mice

To address whether inhibition of muscle necrosis and inflammation resulted in functional improvement in limb muscles, we compared hind limb grip strength in four groups of mice at baseline (8 wk of age) and 4 wk (12 wk of age) and 6 wk (14 wk of age) after various interventions (Fig. 5A). At the baseline 8 wk of age, hind limb grip strength (g) was significantly higher in wild-type mice (118.7±14.7) than in mdx mice (77.3±7.7, P<0.001). Four weeks later (at age 12 wk), hind limb grip strength of imatinib-treated mdx mice (118.3±15.1) was significantly higher than PBS-treated (97.9±7.5, P<0.001) and untreated (93.7±4.5, P<0.001) mdx mice, although it was still lower than wild-type mice (128.0±4.8). Six weeks after interventions (at age 14 wk), hind limb grip strength was still significantly higher in the imatinib group (120.3±8.7) than in the PBS-treated (107.4±8.4, P=0.009) and untreated (109.7±3.2, P=0.03) mdx groups, despite the occurrence of weight loss most likely due to chemical peritonitis (see Materials and Methods). Grip strength, adjusted for body weight (g/g), showed a greater functional benefit from imatinib treatment (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Imatinib improved hind limb grip strength in mdx mice. Bar graph showed significant improvement of hind limb grip strength in mdx mice after 4 and 6 wk of imatinib treatment as compared with PBS-treated and untreated mdx mice, although it was still lower than in wild-type BL10 mice (A). Improvement was greater after adjustment for body weight (g/g) (B). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

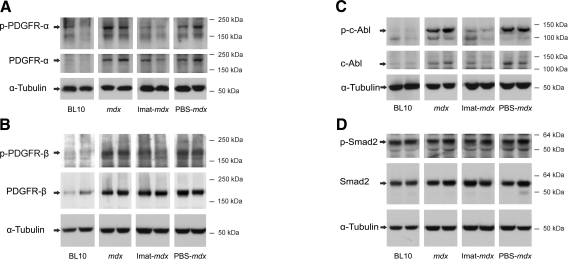

Imatinib inhibited phosphorylation of PDGFR-α, PDGFR-β, and c-abl but not Smad2 in mdx diaphragm

Imatinib selectively and competitively blocks the ATP binding sites of several tyrosine kinases, including c-abl, PDGFRs, and c-kit in various tissues. C-kit is irrelevant to skeletal muscle. To address whether the phosphorylation of c-abl and PDGFRs is inhibited by systemic imatinib in the skeletal muscle of mdx mice, we performed Western blot using proteins extracted from diaphragm muscles at 14 wk of age (Fig. 6). PDGFR-α, PDGFR-β, and c-abl were expressed in the diaphragm muscle, and the total protein levels of these tyrosine kinase receptors were increased in mdx as compared with wild-type mice, supporting a functional role of these signaling molecules in the pathogenesis of muscular dystrophy in mdx mice. Phosphorylation of PDGFR-α, PDGFR-β, and c-abl was inhibited by imatinib but not by PBS treatment. Consistent with the findings from animal models of renal and pulmonary fibrosis (5, 6), phosphorylation of Smad2 was unaffected by imatinib treatment in mdx diaphragm. We concluded that imatinib did inhibit PDGFRs and c-abl but not Smad2 in mdx skeletal muscle.

Figure 6.

Imatinib inhibited phosphorylation of c-abl and PDGFRs but not Smad2 in mdx diaphragm. Western blot showed increased protein expression of PDGF receptor-α (A), β (B), and c-abl (C) in mdx diaphragm as compared with wild-type controls. The expression of phosphorylated PDGFR-α (A), β (B), and c-abl (C) but not Smad2 (D) was inhibited by imatinib but not by PBS treatment.

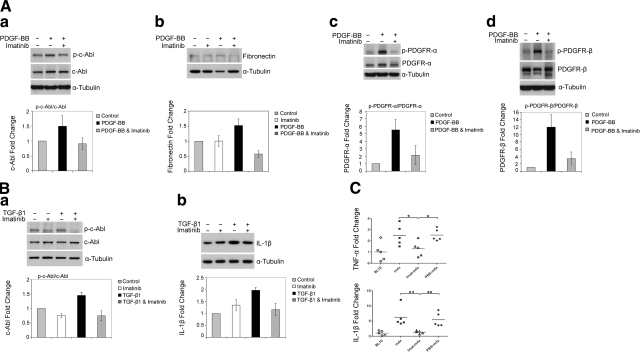

Imatinib inhibited c-abl and PDGFR phosphorylation and suppressed fibronectin and IL-1β expression in mdx diaphragm fibroblasts and wild-type peritoneal macrophages

We next addressed whether the antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effects of imatinib seen in mdx skeletal muscles were mediated by blocking c-abl and PDGFRs in inflammatory cells and skeletal muscle fibroblasts. It has been reported by our lab and others that the expression of PDGF and TGF-β ligands is up-regulated in the necrotic, inflammatory, and regenerating areas of skeletal muscles deficient in dystrophin (17, 26). These ligands are known autocrine and paracrine cytokines acting on a wide diversity of cells. The cells directly involved in fibrosis and inflammation in mdx skeletal muscle are mostly fibroblasts and macrophages. The effects of imatinib on c-abl and PDGFR kinases were then evaluated in primary cultures of mdx diaphragm fibroblasts and wild-type peritoneal macrophages. Phosphorylated c-abl, PDGFR-α, and PDGFR-β were detected in cultured fibroblasts at a low level, and the expression was markedly stimulated by PDGF-BB treatment (Fig. 7Aa, c, d), but less so by TGB-β1 (data not shown). The stimulation of expression of these phosphorylated receptors by PDGF-BB was markedly attenuated by imatinib (Fig. 7Aa, c, d), which was accompanied by reduced fibronectin expression (Fig. 7Ab). Phosphorylated c-abl, but not PDGFR, was also detected at a low level in cultured microphages. TGF-β1 stimulated phosphorylation of c-abl in macrophages, and this effect was markedly attenuated by imatinib, which was accompanied by reduced IL-1β expression (Fig. 7B). These in vitro findings indicate that imatinib targeted c-abl and PDGFRs in fibroblasts and macrophages to suppress extracellular matrix protein and inflammatory cytokine expression. TNF-α and IL-1β are major inflammatory cytokines, and their expression in dystrophic muscles lies downstream of inflammatory growth factor receptors. TNF-α has also been implicated in the initiation of muscle necrosis in mdx mice, as anti-TNF-α therapies protected against skeletal muscle necrosis in mdx mice (27, 28). In addition, imatinib has been shown to inhibit TNF-α mRNA expression in a hepatitis mouse model. To address whether imatinib inhibited TNF-α and IL-1β gene expression in association with reduced muscle necrosis and inflammation in mdx mice, we performed quantitative RT-PCR. TNF-α and IL-1β mRNA expression was up-regulated 2.5-fold and 6.3-fold, respectively, in diaphragm of mdx mice as compared with wild-type controls, consistent with roles of these inflammatory cytokines in muscle dystrophy. The up-regulation of TNF-α and IL-1β was greatly attenuated (reduced by 81.3% for TNF-α and 93.7% for IL-1β, P<0.05) by imatinib but not significantly by PBS (Fig. 7C). So imatinib treatment did inhibit TNF-α and IL-1β gene expression in mdx diaphragm. These in vitro and in vivo findings support the concept that the antifibrotic and antiinflammatory effects of imatinib seen in the skeletal muscle of mdx mice is mediated, at least in part, by inhibiting c-abl and PDGFR signaling pathways and fibrotic and inflammatory cytokine expression in fibroblasts and macrophages.

Figure 7.

Imatinib inhibited phosphorylation of c-abl and PDGFRs and suppressed expression of fibronectin and IL-1β in primary cultures of mdx diaphragm fibroblasts and wild-type macrophages. A) Western blot showed PDGF-BB induced phosphorylation of c-abl (a), PDGFR-α (c), and PDGFR-β (P<0.05) in cultured mdx diaphragm fibroblasts (d), and these effects were attenuated by imatinib treatment, which also significantly inhibited fibronectin protein expression (b) (P<0.05); n = 4–5 each. B) Western blot showed TGF-β induced c-abl phosphorylation (P<0.01) in cultured peritoneal macrophages(a), and this effect was inhibited by imatinib treatment, which also significantly inhibited Il-1β (P<0.01) protein expression (b); n = 4–5 each. C) Quantitative RT-PCR showed a higher mRNA expression level of TNF-α and IL-1β in mdx diaphragm than in wild-type BL10 controls. The increase of TNF-α and IL-1β mRNA expression was significantly attenuated by imatinib but not by PBS treatment. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Imatinib, a revolutionary targeted antineoplastic therapy, has been shown to be a promising antiinflammatory and antifibrotic agent by a number of animal studies. The results from the present study suggest that imatinib is also a promising therapy for DMD by ameliorating muscle necrosis, inflammation, and fibrosis associated with dystrophin deficiency.

Imatinib substantially attenuated the early development of diaphragm fibrosis in mdx mice. It inhibited phosphorylation of PDGF receptors and c-abl in mdx diaphragm and cultured diaphragm fibroblasts accompanied by reduced extracellular matrix protein expression, which is the likely mechanism underlying its antifibrotic effect. The findings support the concept that similar to the fibrotic disorders in other tissues, including kidney, lung, liver, and skin, fibrosis in skeletal muscle associated with DMD is also growth factor-dependent, and modifying these growth factor signaling pathways may represent an important therapeutic approach for DMD. TGF-β and PDGF are two major growth factors driving tissue fibrosis. Imatinib can block both to represent a potentially effective therapy for treating human fibrotic disorders. This hypothesis is supported by a number of in vitro and in vivo studies. Imatinib inhibited cultured fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix gene expression induced by both TGF-β (5, 6, 13) and PDGF (12, 13). Imatinib substantially inhibited experiment renal (6), pulmonary (5, 11), hepatic (12, 29), and skin (13) fibrosis. The antifibrotic effect of imatinib in these studies was mediated by blocking PDGFR and c-abl phosphorylation and their downstream fibrogenic gene expression. The present study also demonstrated an antifibrotic effect of imatinib on mdx diaphragm muscle, and inhibition of phosphorylation of PDGFRs and c-abl in mdx diaphragm and cultured diaphragm fibroblasts. Our findings strongly suggest that PDGF and c-abl signaling pathways also play critical roles in the pathogenesis of mdx diaphragm fibrosis associated with dystrophin deficiency. It has been shown that c-abl is a downstream target responsive to PDGFR activation and that c-abl signaling pathway also represents a non-Smad pathway mediating the fibrogenic effect of TGF-β (5, 6). This pathway, rather than the Smad pathway, was inhibited by imatinib (5, 6). Consistent with these findings, phosphorylation of Smad 2 was unaffected by imatinib in mdx diaphragm or cultured mdx diaphragm fibroblasts (data not shown).

The antifibrotic effect of imatinib on mdx diaphragm and the inhibition of PDGFR and c-abl phosphorylation are consistent with previous reports, which also suggested important roles of TGF-β and PDGF signaling in the pathogenesis of muscle fibrosis in DMD. Gene and protein expression of TGF-β and PDGF, as well as their receptors, was up-regulated in inflammatory cells and regenerating fibers of skeletal muscles of DMD patients and mdx mice (21, 26, 30, 31). Anti-TGF-β therapies, decorin (32), TGF-β antibody (33), and an angiotensin II receptor inhibitor (Losartan) (34), significantly reduced diaphragm fibrosis and fibrogenic gene expression in mdx mice. Since imatinib inhibits both PDGF and c-abl-mediated TGF-β fibrogenic pathways, it can be potentially more potent than these anti-TGF-β therapies.

One major concern about altering TGF-β signaling is that inhibition of this signaling pathway may worsen inflammation (33). TGF-β 1 is not only a profibrotic cytokine but also an immunosuppressive cytokine. Mice deficient in TGF-β1 die of multifocal inflammation around 3–4 wk of age (35, 36). However, inflammation in skeletal muscle of mdx mice and in murine hepatitis (10) and lupus models (8, 9) was reduced by imatinib treatment, suggesting that although c-abl is involved in the profibrotic pathway of TGF-β signaling, it may not be a part of the antiinflammatory pathway of TGF-β. In addition, imatinib may alter other inflammatory cytokines and their signaling pathways to exert its antiinflammatory effect. It has been shown that imatinib attenuated LPS-induced TNF-dependent acute hepatitis by inhibiting TNF-α mRNA and protein expression (10). TNF-α is an early proinflammatory cytokine, which plays an important role in tissue necrosis and inflammation. It also appears to play a pathogenic role in muscle necrosis, based on the findings that anti-TNF-α therapies reduced and delayed the onset of muscle necrosis in mdx mice (27, 28). IL-1β is another inflammatory cytokine that is markedly up-regulated in dystrophic muscles, suggesting its active function in muscle inflammation. In the present study, imatinib treatment greatly reduced the area of muscle necrosis and inflammation and serum CK level of mdx mice. This reduction was accompanied by marked down-regulation of mRNA expression of TNF-α and IL-1β, which suggests that imatinib might inhibit muscle necrosis and subsequent inflammation, at least in part, by down-regulating TNF-α and IL-1β gene expression. To support this concept further, our in vitro study showed that imatinib suppressed c-abl phosphorylation in peritoneal macrophages induced by TGF-β, and the suppression was accompanied by reduced IL-1β protein expression. It has also been shown by others that imatinib inhibited the functional capacity of human monocytes in vitro and reduced TNF-α expression in these cells (37). However, the mechanism by which imatinib down-regulates TNF-α and IL-1β expression is not entirely clear. In muscular dystrophies, muscle necrosis, inflammation, and fibrosis are probably linked. Muscle necrosis and inflammation induce growth factor and cytokine production to increase collagen deposition for tissue injury repair. Chronic muscle necrosis and inflammation could lead to excessive collagen deposition and muscle fibrosis. Therefore, reduced muscle necrosis and inflammation observed in the present study might have also contributed to the reduced endomysial fibrosis.

Reduced muscle pathology resulted in improved muscle function as demonstrated by significantly increased hind limb grip strength in imatinib-treated mdx mice. The majority of muscle cells both in untreated and imatinib-treated mdx mice showed central nucleation on morphological examination, which means they were regenerating or regenerated, with no obvious effect of imatinib on muscle regeneration. It is thus plausible to speculate that the improvement of hind limb grip strength most likely resulted from amelioration of limb muscle necrosis and inflammation. The finding suggests that ameliorating muscle inflammation and fibrosis may indeed represent a viable therapeutic approach for DMD to improve clinical phenotype. In this regard, imatinib is a novel, available, and potentially effective therapy for DMD, because it attenuated both muscle necrosis inflammation and muscle fibrosis in mdx mice. It is FDA-approved, safe, and readily absorbed by oral administration. Oral administration would eliminate the side effect of chronic chemical peritonitis from intraperitoneal injections as encountered in the present study. Imatinib is potentially superior to other anti-TGF-β therapies for reducing fibrosis, because it does not worsen inflammation but rather reduces inflammation. Although imatinib attenuated fibrosis in a number of disease animal models, including renal, pulmonary, liver, and skin fibrosis, its antifibrotic effect has not yet been demonstrated in human fibrotic disorders through clinical trials. The finding that imatinib markedly reduced bone marrow fibrosis in patients with CML, independent of the cytogenic response (7), is encouraging. It suggests that imatinib has a potential to exert antifibrotic effect on human fibrotic disorders. Clinical trials would be needed to test whether imatinib can reduce muscle inflammation and fibrosis and improve muscle function and phenotype in patients with DMD. Further animal study of treating old mdx mice with imatinib would also be helpful to determine whether imatinib can reverse diaphragm fibrosis, and this study is currently ongoing. This line of animal and human studies may eventually provide a steroid-sparing agent and broaden therapeutic options for DMD.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NIH grants K08 NS049346 (L.Z.), and K24 NS51400 (R.M.R.), MDA (award 91682) (L.Z.), and The Frankino Charity Foundation (L.Z.). We thank our statistician, Dr. Jianbo Li, for his assistance in statistical analysis.

References

- Emery A E. Population frequencies of inherited neuromuscular diseases—a world survey. Neuromuscul Disord. 1991;1:19–29. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(91)90039-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery A. New York: Oxford University Press; Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Druker B J. Imatinib as a paradigm of targeted therapies. Adv Cancer Res. 2004;91:1–30. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(04)91001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner J C. Regulation of PDGF and its receptors in fibrotic diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:255–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels C E, Wilkes M C, Edens M, Kottom T J, Murphy S J, Limper A H, Leof E B. Imatinib mesylate inhibits the profibrogenic activity of TGF-beta and prevents bleomycin-mediated lung fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1308–1316. doi: 10.1172/JCI19603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Wilkes M C, Leof E B, Hirschberg R. Imatinib mesylate blocks a non-Smad TGF-beta pathway and reduces renal fibrogenesis in vivo. FASEB J. 2005;19:1–11. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2370com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueso-Ramos C E, Cortes J, Talpaz M, O'Brien S, Giles F, Rios M B, Medeiros L J, Kantarjian H. Imatinib mesylate therapy reduces bone marrow fibrosis in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cancer. 2004;101:332–336. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadanaga A, Nakashima H, Masutani K, Miyake K, Shimizu S, Igawa T, Sugiyama N, Niiro H, Hirakata H, Harada M. Amelioration of autoimmune nephritis by imatinib in MRL/lpr mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3987–3996. doi: 10.1002/art.21424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoja C, Corna D, Rottoli D, Zanchi C, Abbate M, Remuzzi G. Imatinib ameliorates renal disease and survival in murine lupus autoimmune disease. Kidney Int. 2006;70:97–103. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf A M, Wolf D, Rumpold H, Ludwiczek S, Enrich B, Gastl G, Weiss G, Tilg H. The kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate inhibits TNF-{alpha} production in vitro and prevents TNF-dependent acute hepatic inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13622–13627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501758102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahi A, Li M, Ping G, Plathow C, Domhan S, Kiessling F, Lee L B, McMahon G, Grone H J, Lipson K E, Huber P E. Inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor signaling attenuates pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2005;201:925–935. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiji H, Noguchi R, Kuriyama S, Ikenaka Y, Yoshii J, Yanase K, Namisaki T, Kitade M, Masaki T, Fukui H. Imatinib mesylate (STI-571) attenuates liver fibrosis development in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G907–G913. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00420.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distler J H, Jungel A, Huber L C, Schulze-Horsel U, Zwerina J, Gay R E, Michel B A, Hauser T, Schett G, Gay S, Distler O. Imatinib mesylate reduces production of extracellular matrix and prevents development of experimental dermal fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:311–322. doi: 10.1002/art.22314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnwath J W, Shotton D M. Muscular dystrophy in the mdx mouse: histopathology of the soleus and extensor digitorum longus muscles. J Neurol Sci. 1987;80:39–54. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(87)90219-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulton G R, Morgan J E, Partridge T A, Sloper J C. The mdx mouse skeletal muscle myopathy: I. A histological, morphometric and biochemical investigation. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1988;14:53–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1988.tb00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen M J, Jaros E. Ultrastructure of the skeletal muscle in the X chromosome-linked dystrophic (mdx) mouse. Comparison with Duchenne muscular dystrophy Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 1988;77:69–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00688245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Porter J D, Cheng G, Gong B, Hatala D A, Merriam A P, Zhou X, Rafael J A, Kaminski H J. Temporal and spatial mRNA expression patterns of TGF-beta1, 2, 3 and TbetaRI, II, III in skeletal muscles of mdx mice. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont-Versteegden E E, McCarter R J. Differential expression of muscular dystrophy in diaphragm versus hindlimb muscles of mdx mice. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15:1105–1110. doi: 10.1002/mus.880151008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stedman H H, Sweeney H L, Shrager J B, Maguire H C, Panettieri R A, Petrof B, Narusawa M, Leferovich J M, Sladky J T, Kelly A M. The mdx mouse diaphragm reproduces the degenerative changes of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature. 1991;352:536–539. doi: 10.1038/352536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Huang D, Matsui M, He T T, Hu T, Demartino J, Lu B, Gerard C, Ransohoff R M. Severe disease, unaltered leukocyte migration, and reduced IFN-gamma production in CXCR3-/- mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;176:4399–4409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Rafael-Fortney J A, Huang P, Zhao X S, Cheng G, Zhou X, Kaminski H J, Liu L, Ransohoff R M. Haploinsufficiency of utrophin gene worsens skeletal muscle inflammation and fibrosis in mdx mice. J Neurol Sci. 2008;264:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona A E, Sasse M E, Mizutani M, Cardona S M, Liu L, Savarin C, Hu T, Ransohoff R M. Scavenging roles of chemokine receptors: chemokine receptor deficiency is associated with increased levels of ligand in circulation and tissues. Blood. 2008;112:256–263. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-118497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe G, O'Neil J, Hoff H F. Inactivation of lysosomal proteases by oxidized low density lipoprotein is partially responsible for its poor degradation by mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1506–1512. doi: 10.1172/JCI117490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadic R, Mezzano V, Alvarez K, Cabrera D, Holmgren J, Brandan E. Increase in decorin and biglycan in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: role of fibroblasts as cell source of these proteoglycans in the disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:758–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melone M A, Peluso G, Galderisi U, Petillo O, Cotrufo R. Increased expression of IGF-binding protein-5 in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) fibroblasts correlates with the fibroblast-induced downregulation of DMD myoblast growth: an in vitro analysis. J Cell Physiol. 2000;185:143–153. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200010)185:1<143::AID-JCP14>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Haginoya K, Sun G, Dai H, Onuma A, Iinuma K. Platelet-derived growth factor and its receptors are related to the progression of human muscular dystrophy: an immunohistochemical study. J Pathol. 2003;201:149–159. doi: 10.1002/path.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grounds M D, Torrisi J. Anti-TNFalpha (Remicade) therapy protects dystrophic skeletal muscle from necrosis. FASEB J. 2004;18:676–682. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1024com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgetts S, Radley H, Davies M, Grounds M D. Reduced necrosis of dystrophic muscle by depletion of host neutrophils, or blocking TNFalpha function with Etanercept in mdx mice. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16:591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalo T, Beljaars L, van de Bovenkamp M, Temming K, van Loenen A M, Reker-Smit C, Meijer D K, Lacombe M, Opdam F, Keri G, Orfi L, Poelstra K, Kok R J. Local inhibition of liver fibrosis by specific delivery of a platelet-derived growth factor kinase inhibitor to hepatic stellate cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:856–865. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.114496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernasconi P, Torchiana E, Confalonieri P, Brugnoni R, Barresi R, Mora M, Cornelio F, Morandi L, Mantegazza R. Expression of transforming growth factor-beta 1 in dystrophic patient muscles correlates with fibrosis. Pathogenetic role of a fibrogenic cytokine. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1137–1144. doi: 10.1172/JCI118101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidball J G, Spencer M J, St Pierre B A. PDGF-receptor concentration is elevated in regenerative muscle fibers in dystrophin-deficient muscle. Exp Cell Res. 1992;203:141–149. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90049-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin L E, Williams J E, Deering M, Brazeau D, Koury S, Martinez D A. Localization and early time course of TGF-beta 1 mRNA expression in dystrophic muscle. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30:645–653. doi: 10.1002/mus.20150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreetta F, Bernasconi P, Baggi F, Ferro P, Oliva L, Arnoldi E, Cornelio F, Mantegazza R, Confalonieri P. Immunomodulation of TGF-beta 1 in mdx mouse inhibits connective tissue proliferation in diaphragm but increases inflammatory response: implications for antifibrotic therapy. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;175:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn R D, van Erp C, Habashi J P, Soleimani A A, Klein E C, Lisi M T, Gamradt M, ap Rhys C M, Holm T M, Loeys B L, Ramirez F, Judge D P, Ward C W, Dietz H C. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade attenuates TGF-beta-induced failure of muscle regeneration in multiple myopathic states. Nat Med. 2007;13:204–210. doi: 10.1038/nm1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni A B, Huh C G, Becker D, Geiser A, Lyght M, Flanders K C, Roberts A B, Sporn M B, Ward J M, Karlsson S. Transforming growth factor beta 1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:770–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shull M M, Ormsby I, Kier A B, Pawlowski S, Diebold R J, Yin M, Allen R, Sidman C, Proetzel G, Calvin D, Annunziata N N, Doetschman T. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359:693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar A L, Doherty K V, Hughes T P, Lyons A B. Imatinib inhibits the functional capacity of cultured human monocytes. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005;83:48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2004.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]