Abstract

The present study was undertaken to investigate the rate and mode of degradation of individual histatin proteins in whole saliva to establish the impact on its functional domains. Pure synthetic histatins 1, 3, and 5 were incubated with whole saliva supernatant as the enzyme source, and peptides in the resultant digests were separated by reverse-phase-HPLC and structurally characterized by electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. The overall Vmax/Km ratios, a measure of proteolytic efficiency, were on the order of histatin-5 > histatin-3 > histatin-1. Mathematical models predict that histatins 1, 3, and 5 levels in whole saliva stabilize at 5.1, 1.9, and 1.2 μM, representing 59, 27, and 11% of glandular histatins 1, 3, and 5 levels, respectively. Monitoring of the appearance and disappearance of histatin fragments yielded the identification of the first targeted enzymatic cleavage sites as K13 and K17 in histatin 1, R22, Y24, and R25 in histatin 3, and Y10, K11, R12, K13, H15, E16, K17, and H18 in histatin 5. The data indicate that metal-binding, antifungal, and wound-healing domains are largely unaffected by the primary cleavage events in whole saliva, suggesting a sustained functional activity of these proteins in the proteolytic environment of the oral cavity.—Sun, X., Salih, E., Oppenheim, F. G., Helmerhorst, E. J. Kinetics of histatin proteolysis in whole saliva and the effect on bioactive domains with metal-binding, antifungal, and wound-healing properties.

Keywords: oral, proteolytic, enzymes, proteins, proteomics

Proteolytic processing of proteins is a major biological mechanism leading to the loss, alteration, or activation of protein function. Such processing involving protein maturation and turnover has major implications for a variety of cell biological processes (1, 2). One of the body fluids with pronounced proteolytic activity is human oral fluid or whole saliva (WS). In contrast to many other biological fluids, WS is nonsterile and has a very complex composition comprising exocrine secretions from the major and minor salivary glands, gingival crevicular fluid, and oral epithelial and microbial cells and their products (3). Proteases present in WS may derive from any of these contributing sources (4,5,6). Despite the diverse array of potential protease origins in WS, the overall enzymatic specificity of this fluid shows a remarkable consistency among healthy subjects (7). This finding indicates that the proteolytic activity of the oral environment is dictated by a common biological principle and is amenable to molecular characterization.

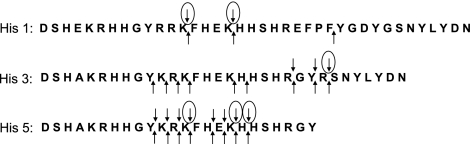

One family of endogenous salivary proteins being extensively cleaved in WS comprises histatins (8,9,10,11). Histatins 1, 3, and 5 are the most prominent histatins secreted by the parotid and submandibular/sublingual salivary glands. Prior structure-function studies on these proteins have identified distinct domains with specific functional properties (Fig. 1). Histatin 1 is fully phosphorylated at serine 2. Like other phosphorylated salivary proteins, histatin 1 has been implicated in the maintenance of tooth enamel mineral and pellicle formation (12). All histatins are enriched in the amino acid histidine, an amino acid capable of complexation of divalent metal ions. The ATCUN motif, which complexes Cu2+ and Ni2+ ions, is located at the N terminus of histatins 3 and 5 and is represented by NH2-Asp-Ser-His-. Furthermore, two zinc-binding domains of the general sequence HEXXH are present in histatin 1, and one such motif is present in histatins 3 and 5 (13,14,15,16). Zinc plays a role in taste perception (17). Histatin complexation of metal ions in saliva may furthermore eliminate cofactors for enzymes and essential nutrients for microbial growth. Consistent with this activity, histatins are potent inhibitors of matrix metalloproteases (18) and exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities toward a variety of aerobic bacteria and fungi (19, 20). Among the histatins, histatin 5 displays the highest antifungal activity (21). Antifungal domains have been located in the N-terminal and middle regions. A segment spanning residues 4–15, designated P-113, has been evaluated for therapeutic efficacy in in vivo oral candidiasis (22, 23). Recently it has been reported that histatins 1 and 3, but not histatin 5, exhibit wound closure activities in vitro (24). The inactivity of histatin 5, comprising the N-terminal 24 residues of histatin 3, indicated that the C-terminal 8 residues in histatin 3 are essential for wound closure activity. Because the last 7 of these 8 residues are homologous with the C terminus of histatin 1, it is tempting to speculate that this 7-residue segment is responsible for the wound-healing properties of histatins 1 and 3.

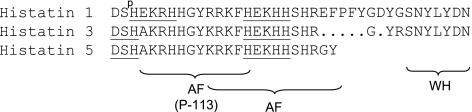

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequences of histatins 1, 3, and 5 and indication of functionally important peptide regions. Sp, phosphorylated serine residue; DSH, metal-binding ATCUN motif; HEXXH, zinc-binding region; AF, antifungal domain; WH, wound-healing domain.

With the discovery of the in vitro wound-healing activity, a renewed interest in histatins has been raised. In addition, the antifungal and metal-binding capacities of the intact histatins are well established. Thus, there is broad potential for therapeutic applications, but a lack of critical data taking into account the proteolytic activities in saliva and the susceptibilities of histatins to such activities. If and how histatin function is affected by salivary proteolysis is dependent on their rate and mode of degradation. The proteolysis cascade of histatin 3 has been indirectly derived from the histatin peptide profiles in WS (8, 10), and no cascades for histatin 1 have been reported. Saliva degradation studies are crucial to anticipate biological activity vs. neutralization of the activities of salivary proteins in the oral environment. In particular, it will be of interest to establish the effect of salivary proteases on histatin metal-binding, antifungal, and wound-healing domains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Saliva collection

Stimulated WS was obtained from 5 subjects. All enrolled subjects presented with good oral health without overt signs of gingival inflammation or other oral conditions. Informed consent was obtained before sample collection according to approved protocols of the institutional review board at Boston University Medical Center. WS (5 ml) was collected between 10 and 11 A.M. at least 1 h after the last meal. Salivary secretion was stimulated by mastication using 1 g of paraffin wax (Parafilm; American National Can, Chicago, IL, USA). Immediately after collection, WS was cleared from particulate matter such as bacteria and desquamated epithelial cells by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The resultant WS supernatant (hereafter referred to as WSS) was pooled. Parotid secretion (PS) was collected from two healthy subjects with the aid of a Curby cup positioned over the orifice of the Stensen’s duct. Secretion was stimulated with sour candies (Jolly Rancher; Hershey’s, Hershey, PA, USA) and collected in graduated tubes placed on ice.

Proteolysis of histatins in WSS

To study the proteolysis of endogenous histatins in PS/WSS mixtures, equal volumes (1 ml each) were combined and incubated in a 37°C water bath. After 0, 30, 60, and 90 min of incubation, 100-μl aliquots were removed and boiled, followed by cationic PAGE analysis. To investigate the degradation of each of the histatins in more detail, synthetic histatins 1, 3, and 5 (American Peptide Company, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) were added to WSS to a final concentration of 200 μg/ml. After 0 and 1.5 h of incubation, 100-μl aliquots were removed and boiled, followed by reverse-phase (RP)-HPLC analysis. To establish the overall kinetic parameters (Vmax and Km) of histatin degradation in WSS, histatins 1, 3, or 5 were added to undiluted WSS to final concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 μM. Samples were incubated at 37°C, and aliquots of 100 μl were removed and boiled every 2 or every 4 min depending on the rate of degradation. Samples were analyzed by RP-HPLC, and intact histatin levels were quantitated from the peak heights. For the structural characterization of the proteolytic degradation fragments, synthetic histatins 1, 3, or 5 (400 μg/ml) were added to 1:10 diluted WSS. Samples were incubated at 37°C, and 100-μl aliquots were removed and boiled after various incubation times ranging from 0 to 72 h and analyzed by RP-HPLC. Individual peaks containing histatin proteolytic fragments were collected and characterized by electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS).

Cationic PAGE

The 100-μl PS/WSS sample aliquots were dried using a Vacufuge concentrator (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY, USA) and resuspended in sample buffer containing 0.04% methyl green (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in 40% sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA). Positively charged proteins were separated by 15% cationic PAGE as described previously (25, 26). This native gel system, in contrast to SDS-PAGE, facilitates excellent separation of the individual histatins and separates histatins from negatively charged proteins that do not migrate into the gel. Gel polymerization was accelerated by exposing the gels to a light source (60 W). Electrophoresis was carried out at a constant voltage of 120 V. The gels were stained with 0.1% (w/v) Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 in 10% (v/v) acetic acid and 40% (v/v) methanol and destained in the same solution not containing the dye.

RP-HPLC

The 100-μl boiled sample aliquots to be analyzed by RP-HPLC were cooled, mixed with 900 μl of buffer A (0.1% TFA), and filtered through a 0.22-μm filter (Pall Cooperation, Ann Arbor, MI, SUA). All samples were loaded on a C-18 column (TSK-GEL 5-μm, ODT-120T, 4.6 mm × 250 mm, TosoHaas, Montgomeryville, PA, USA) connected to a high-performance liquid chromatograph model 715 (Gilson, Middleton, WI, USA). Proteins/peptides were eluted using a linear gradient from 0 to 55% buffer B (80% acetonitrile and 0.1% TFA) over a 74-min time interval at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Absorbances were monitored at 219 and 230 nm, and the eluate was collected in 1-ml aliquots. Fractions containing protein peaks were lyophilized using the Vacufuge concentrator (Eppendorf) and subjected to ESI-MS/MS. All quantitative analyses were carried out using the Unipoint software (version 3.30; Gilson) with a default baseline setting and a sensitivity threshold of 2.5%.

ESI-MS/MS analysis

To structurally characterize histatin fragments, lyophilized RP-HPLC fractions were dissolved in 20 μl of a solvent containing 40% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid. ESI-MS/MS was carried out using an LTQ-linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA, USA). Because histatin fragments are small and typically exhibit multiple charges, their standard identification using Bioworks software was difficult, and therefore such samples were analyzed in the static mode. For this purpose, samples were loaded into a PicoTip emitter (New Objective, Woburn, MA, USA) with a tip of 4 μm in diameter, followed by ESI-MS using an electrospray voltage of 2.3 kV. Full mass spectrometry (MS) scans in the m/z range of 300-2000 were obtained, and prominent ions above 10% relative abundance were selected manually for MS/MS analysis. In addition, automatic MS/MS analyses were conducted for each MS scan.

MS data analysis

The charges of individual fragment ions in the full mass spectrum were determined using the zoom option provided in the Bioworks software (version 3.3.1, Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA, USA) to visualize the mass differences of the carbon isotope variants of the same ion fragment. Subsequently, the masses of the distinct peptides were calculated and matched with all possible theoretical masses of histatin 1, 3, and 5 fragments by using the FindPept tool from ExPASy (http://ca.expasy.org/tools/findpept.html). To confirm that the identifications were correct, the MS/MS spectrum obtained was compared with the theoretical MS/MS spectrum of that fragment ion generated in silico using the MS product tool available at http://prospector.ucsf.edu/. The minimal requirements for the identification of a particular peptide were at least three consecutive b ions or y ions matching the theoretical MS/MS spectrum and >50% of the total ions well above background level.

RESULTS

Degradation of endogenous histatins in WSS

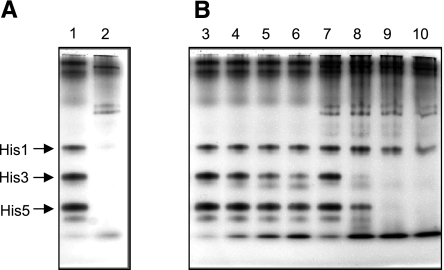

On secretion, glandular salivary secretions come into contact with host resident salivary proteases not encountered in the sterile glandular environment. To mimic these in vivo events and their effect on protein stability, PS was mixed with WSS and incubated, and the integrity of the histatin proteins was visualized as a function of time by cationic PAGE. Figure 2 shows that histatins rapidly disappear in the PS/WSS mixture compared with their relative stability in sterile glandular PS, supporting evidence for the extensive proteolytic activity in WSS and the sensitivity of histatins to such activities.

Figure 2.

Proteolysis of endogenous histatins in PS in the presence of WSS enzymes. Pooled PS was mixed in a 1:1 ratio (v/v) with deionized water or with pooled WSS, and after various incubation times the histatin levels were visualized by cationic PAGE. A) Lane 1, endogenous histatin levels in pooled PS; lane 2, endogenous histatin levels in pooled WSS. B) Lanes 3–6, PS/water mixture incubated for 0, 30, 60, and 90 min; lanes 7–10, PS/WSS mixture incubated for the same time intervals. Arrows indicate intact histatins (His) 1, 3, and 5.

Initial studies on histatin proteolysis in WSS

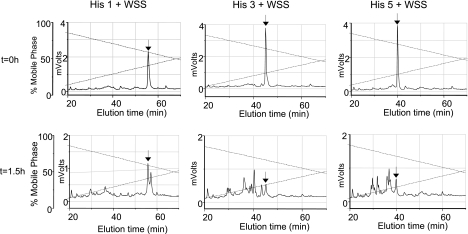

To assess and compare histatin 1, 3, and 5 proteolysis in the WS environment in more detail, pure synthetic histatins 1, 3, or 5 were added to WSS to observe their degradation over time. In the 1.5-h chromatograms distinct fragmentation patterns could be observed for each of the histatin proteins (Fig. 3). Consistent with the observations in cationic PAGE (Fig. 2) and previous reports (27, 28), histatin 1 appeared more resistant to proteolysis than histatins 3 and 5. From the reduction in the peak heights of histatins 1, 3, and 5 (indicated with arrows), it could be estimated that ∼50% of histatin 1 was proteolytically degraded, whereas 75% of histatin 3 and histatin 5 was digested after 1.5 h of incubation. Despite their structural similarities, the three histatin proteins showed remarkable differences in their degradation spectra. For example, histatin 1 proteolysis yielded a major degradation fragment eluting just after histatin 1, whereas the degradation of histatins 3 and 5 generated multiple fragments that all eluted before the parent proteins. Subsequent experiments were designed to gain quantitative and structural information on the peptides produced over time.

Figure 3.

Proteolysis of synthetic histatins (His) 1, 3 and 5 added to pooled WSS. Histatins were individually added to WSS to final concentrations of 200 μg/ml. Aliquots of 100 μl were boiled and analyzed by RP-HPLC after 0 h (top panels) and 1.5 h (bottom panels) of incubation. Black arrows indicate intact histatin 1 (left panels), histatin 3 (center panels), or histatin 5 (right panels) levels.

Overall kinetic parameters of histatin degradation in WSS

To quantitate the differences in proteolytic susceptibilities of histatins 1, 3, and 5, the overall kinetic parameters (Km and Vmax) of their proteolysis in WSS were determined. Such classic enzyme kinetic studies are usually reserved for pure enzyme preparations. The purpose of conducting such studies with WSS, yielding the apparent (overall) kinetic parameters of the mixture of proteases, is to compare the degradation characteristics of histatins 1, 3, and 5. For all comparisons, one batch of WSS was used. The initial rate of degradation (Vi) was determined for each histatin starting concentration and plotted against the respective concentrations to obtain the enzyme saturation curves (Fig. 4A). The data were also plotted in a Lineweaver-Burk plot (Fig. 4B). The overall kinetic parameters, Km and Vmax, were determined for each of the histatins from the x axis intercept (−1/Km) and the y axis intercept (1/Vmax), respectively (Fig. 4C). The order of the Km values found was histatin 1 > histatin 3 > histatin 5 and the order of the Vmax values found was histatin 3 > histatin 1 ≈ histatin 5. Based on the Km and Vmax values, the Vmax/Km ratios, a measure for the overall proteolytic efficiency, were also calculated (Fig. 4C). The result showed that the catalytic efficiency of WSS proteases toward histatins was on the order of histatin 5 > histatin 3 > histatin 1.

Figure 4.

Overall kinetic parameters of histatin (His) 1, 3, and 5 proteolysis in WSS. Synthetic histatins 1, 3, or 5 were added individually to WSS to final concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 μM. Samples were taken from each sample every 2–4 min and analyzed by RP-HPLC, and intact histatin levels were quantitated by peak height analysis. Initial velocity Vi of histatin disappearance was calculated for each sample containing a particular histatin starting concentration. A) Enzyme saturation curves. B) Lineweaver-Burk plots. C) WSS enzyme kinetic parameters toward histatins 1, 3, and 5.

Temporal and structural characterization of histatin 1 degradation

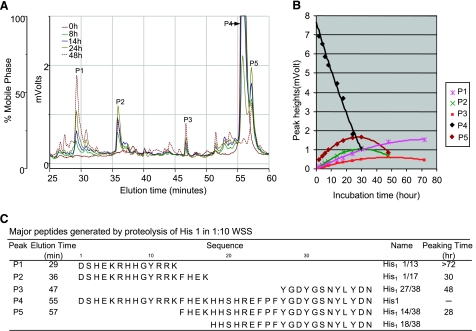

Further degradation experiments were carried out with 1:10 diluted WSS and a relatively high concentration of histatins (400 μg/ml each). A diluted enzyme source was used to retard the proteolysis process, to be able to dissect the otherwise rapid process step by step ex vivo, and to reduce the absorbance of the endogenous histatin peptides to negligible levels. The histatin concentrations added to the diluted WSS sample allowed the visualization of the generated degradation products and their collection for structural analysis. Neither dilution of the enzyme source nor an increase in the substrate concentration is expected to affect protease specificity. Figure 5A shows the RP-HPLC chromatograms of histatin 1 incubated in 1:10 diluted WSS for various time intervals. As proteolysis progressed, the intact histatin 1 peak (P4), eluting at 55 min, gradually decreased, with a concomitant appearance of fragments eluting after 29 min (P1), 36 min (P2), 47 min (P3), and 57 min (P5). In Fig. 5B, the time frame for the appearance and disappearance of each of these peptide peaks is shown. Peptides in peaks P2 and P5 reached their highest point (peaking time) at 30 and 28 h, respectively, before intact histatin 1 disappeared (after ∼40 h). The peaking times of peptides eluting in peaks P1 and P3 lagged behind at >72 and 48 h, respectively. The histatin 1 fragments separated by RP-HPLC were collected, lyophilized, and analyzed by ESI-MS/MS for structural characterization (Fig. 5C). As could be expected, in some cases multiple peptides were identified in one RP-HPLC fraction. Identification of the matching peptide pairs His1 1/13 and His1 14/38 as well as His1 1/17 and His1 18/38 point toward single cleavage events after K13 and K17, indicating that these are primary cleavage sites. The time of peak appearance and disappearance (peaking time) of each of the fragments allows the determination of the temporal sequence of the cleavage events. Whereas K13 is a primary cleavage site, the late peaking time of His1 1/13 (>72 h) indicates that it is also a secondary cleavage product generated from His1 1/17. His1 27/38, the smallest C-terminal peptide identified in P3, exhibited later peaking times than the larger C-terminal fragments in peak 5 indicating that F26 is a secondary cleavage site.

Figure 5.

Temporal and structural characterization of histatin 1 (His 1) degradation in WSS. A) RP-HPLC chromatograms of synthetic histatin 1 (400 μg/ml) incubated for 0, 8, 18, 24, or 48 h in 1:10 diluted WSS. B) Time frame of the appearance and disappearance of individual histatin 1 fragments derived from RP-HPLC peak heights. C) Structural characterization of each of the histatin 1 fragments by ESI-MS/MS. Right column indicates time point at which each fragment reaches maximal peak height (peaking time).

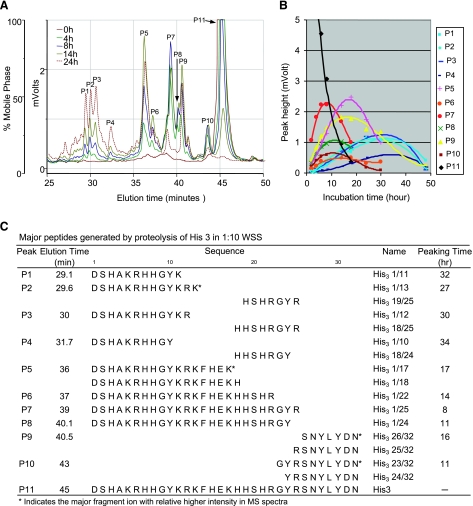

Temporal and structural characterization of histatin 3 degradation

Even though histatin 1 and histatin 3 are similar in structure, histatin 3 proteolysis yielded far more degradation fragments and a distinctly different proteolytic profile than histatin 1 (Fig. 6). In total, 16 fragments were structurally characterized, comprising three peptide pairs (His3 1/22 and 23/32, His3 1/24 and 25/32, and His3 1/25 and 26/32) and 10 unpaired fragments. Peptides that appeared in pairs were all generated in the early phases of histatin 3 degradation, exhibiting peaking times of <20 h. In this early time frame, the single peptides His3 1/17 and 1/18 (both eluting in peak P5) were also formed, but the absence of their matching C termini (His3 18/32 and His3 19/32) indicated that these fragments probably arose from (rapid) secondary cleavages of the larger N-terminal fragments. Peptides with peaking times >20 h all represented small N-terminal fragments as well as middle peptide regions, formed through secondary or subsequent cleavages. Overall, the data indicate that R22, Y24, and R25 are the three primary cleavage sites out of a total of nine cleavage sites identified in histatin 3. Among the three primary cleavage sites, R25 is possibly the most favorable because the His3 1/25 fragment (present in peak P7) is significantly more abundant than the other two primary cleavage products (His3 1/22 and His3 1/24 in peaks P6 and P8, respectively) as judged from their UV absorbances in the HPLC spectrum.

Figure 6.

Temporal and structural characterization of histatin 3 (His 3) degradation in WSS. A) RP-HPLC chromatograms of synthetic histatin 3 (400 μg/ml) incubated for 0, 4, 8, 14, or 24 h in 1:10 diluted WSS. B) Time frame of the appearance and disappearance of individual histatin 3 fragments derived from RP-HPLC peak heights. C) Structural characterization of each of the histatin 3 fragments by ESI-MS/MS. Right column indicates time point at which each fragment reaches maximal peak height (peaking time).

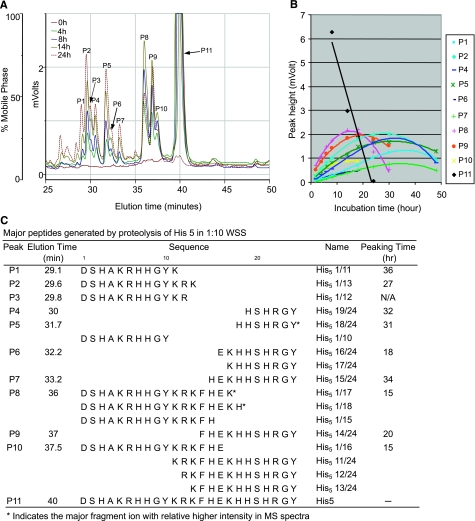

Temporal and structural characterization of histatin 5 degradation

In contrast to histatins 1 and 3, all fragments identified for histatin 5 were present in peptide pairs; i.e., for each N-terminal fragment, the matching C-terminal fragment was found. The cleavage sites identified were Y10, K11, R12, K13, H15, E16, K17, and H18, which appear to be simultaneously targeted by WS enzymes, consistent with our previous observations (7). The results are presented in Fig. 7 to allow comparison with the histatin 1 and 3 fragmentation patterns. Among the eight primary cleavage sites identified, K13, K17, and H18 appear to be the most favorable because the resulting fragments eluting in peaks P2, P4, P5, P8, and P9 were most abundant in the RP-HPLC spectra.

Figure 7.

Temporal and structural characterization of histatin 5 (His 5) degradation in WSS. A) RP-HPLC chromatograms of synthetic histatin 5 (400 μg/ml) incubated for 0, 4, 8, 14, or 24 h in 1:10 diluted WSS. B) Time frame of the appearance and disappearance of individual histatin 5 fragments derived from RP-HPLC peak heights. C) Structural characterization of each of the histatin 5 fragments by ESI-MS/MS. Right column indicates time point at which each fragment reaches maximal peak height (peaking time).

DISCUSSION

Histatin degradation in the oral cavity

Influx, degradation, and clearance are all important parameters to be considered in calculating the survival of proteins in saliva. Precise numbers for all three parameters are difficult to measure and also are known to differ significantly between subjects, at different salivary flow rates, and at different patterns of swallowing. However, by using reported values for resting flow rates and average oral fluid volume (29), average glandular concentrations of histatins 1, 3, and 5 (30), and the kinetic parameters obtained in this study, estimates can be obtained for the fraction of histatins being cleaved and remaining intact at equilibrium.

If histatin levels in WS were only dictated by the influx of newly synthesized histatins from the salivary glands, then the change in histatin concentration Q over time in whole saliva is given by

|

1 |

where V is the oral fluid volume that changes over time t between swallowings, Cg is the average concentration of histatins released by the salivary glands, and F is the salivary flow rate.

By assuming that Michaelis-Menten kinetics apply to the mixture of proteases present in the oral cavity and that proteolysis is the major cause for reduction of histatin levels in WS, then the rate of disappearance v of histatins from WS is given by

|

2 |

The concentration of Q over time, dictated by influx and degradation, is then formulated by

|

3 |

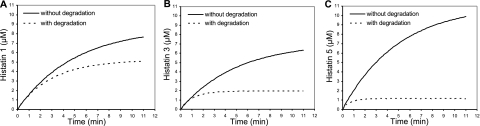

In Fig. 8, Q as a function of t has been plotted for each of the major histatins, starting at the arbitrary point (0, 0). The data illustrate that the combined processes of influx and degradation lead to a steady state at which the histatin concentrations are substantially lower than those in the gland. Histatins 1, 3, and 5 reach a plateau of 5.1, 1.9, and 1.2 μM, respectively. These values represent 59, 27, and 11%, respectively, of the concentrations of their average concentrations in the major glandular secretions, which were set at 8.6, 7.1, and 11.1 μM, respectively, based on earlier reports (30). The calculated theoretical concentrations of histatins at equilibrium in WS closely match reported histatin concentrations in WS (31). These predictions illustrate that proteolysis drastically reduces the histatin concentrations in WS and emphasize the importance of studying the molecular characteristics of the biological fragmentation process.

Figure 8.

Theoretical histatin levels in WS (Q) as a function of time (t) without and with proteolysis. See text for details. Levels without proteolysis were calculated using Eq. 1; those taking proteolysis into account were calculated using Eq. 3. Values used for calculations: F = 12 ml/h; V = 0.9–1.1 ml between swallowings; Cg = 8.6, 7.1, and 11.1 μM for histatins 1, 3, and 5; Km = 47.3, 12.0, and 4.9 μM; Vmax = 0.111, 0.156, and 0.127 μM · s−1. Note that Vmax values are 7.5 times higher than those reported in Fig. 3C to compensate for the 7.5 times higher proteolysis rates in WS compared with those in WSS (42). Concentrations without and with degradation were calculated for histatin 1 (A), histatin 3 (B), and histatin 5 (C).

Histatin fragmentation pathways

The approach followed combined the application of RP-HPLC analysis, allowing unequivocal and direct measurements of fragment abundance, and the use of ESI-MS/MS for their structural characterization. The time of appearance and disappearance of individual degradation fragments enabled the assignment of the first and subsequent targeted cleavage sites (summarized in Fig. 9). Some of the identified fragments generated from histatin 3 have also been found in in vivo peptidomes of various oral fluids (8,9,10, 32). For example, peptides resulting from cleavage after K11, R12, K13, Y24, and R25 have been detected in PS as well as in submandibular/sublingual gland secretions. Whereas some minor processing of the major histatins occurs before their release into the oral cavity, the structural effect of enzymes operating in whole saliva fluid is of a much higher magnitude and functional relevance (33).

Figure 9.

Proteolytic cleavage sites in histatins targeted by human salivary proteases. Arrows pointing up, all identified cleavage sites; arrows pointing down, primary cleavage sites; circled arrows, preferred primary cleavage sites.

Cleavage site specificities

RP-HPLC and MS analysis yielded the intriguing result that the fragmentation pathways of the individual histatins are quite unique. C-terminal cleavages at residues K13 and K17 were identified in all three histatins exhibiting a consensus sequence Y/FXXK↓. These cleavage sites are primary targets in histatins 1 and 5 but are later cleaved in histatin 3. In the latter protein, the primary targets are R22, Y24, and R25. Two of these sites, Y24 (HRGY↓) and R25 (RGYR↓) are only present in histatin 3 and absent from the other major histatins. The fact that in histatin 3 HRGY↓ and RGYR↓are cleaved before the Y/FXXK↓ site is targeted suggests that WS enzymes display a higher affinity for the HRGY↓ and RGYR↓ regions. Indeed, we have confirmed this notion with artificial enzyme substrates (unpublished observations). The absence of the HRGY and RGYR sequences in histatin 1 may in part explain its lower sensitivity to proteolysis compared with that of histatin 3. In general, WSS proteases displayed the highest overall Km value and the lowest Vmax/Km ratio toward histatin 1, providing quantitative evidence that among the major histatins, histatin 1 is least efficiently degraded in the oral environment.

Another interesting observation was the difference in proteolytic processing of homologous protein regions. For instance, R22 (HSHR↓) is present in all three histatins but is only cleaved in histatin 3, emphasizing the importance of flanking amino acid domains for protease recognition. The influence of even more distant domains in the polypeptide chain can be seen by comparing the cleavages occurring in the protein region comprising residues 12–19. Although this domain is identical in all histatins, histatin 1 is cleaved at two sites, histatin 3 at four sites, and histatin 5 at seven sites. It is feasible that differences in protein folding as reported, for example, between histatin 3 and histatin 5 (34) may affect the exposure of particular protein domains to WSS proteases and in part explain differences in cleavage patterns. In addition, WSS is a complex fluid and protein-protein interaction, such as that between the N-terminal region of MUC7 and histatin 1 (35), and the differential binding of histatins 1, 3, and 5 to cysteine-rich domains in MUC5B (36) may also affect interactions with proteases. Thus, the proteolytic degradation of histatins 1, 3, and 5 is the net result of WSS protease specificity and the exposure and accessibility of target protein regions to WSS proteases.

Effect of proteolysis on functional domains

The biological roles of histatin fragments in the oral cavity have been studied in some detail. Fragments His1 18/38, His1 27/38, His5 1/12, His5 1/14, His5 12/24, and His5 15/24, as well as intact histatins 1 and 5, are present in WS and in human enamel pellicle (37). Tooth enamel pellicle is the protein film covering the tooth surface and is important for the mineralization/demineralization processes and for governing dental plaque formation (38,39,40). Most of the histatin fragments found in pellicle or in whole saliva were identified to be generated in the present study, indicating that this ex vivo study is representative of the proteolysis of histatins 1, 3, and 5 in vivo.

It has been reported that histatins are potent competitive inhibitors of host-derived matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 (18). The levels of these enzymes are elevated in saliva of patients with periodontal disease (41). A proposed mechanism of inhibition of MMP-2 and MMP-9 by histatins is based on the zinc-binding motifs (HEXXH) in these proteins (15), which can chelate the zinc ion from the catalytic sites. One of the prominent cleavages in histatin 1, after K17, abolishes one of the two zinc-binding domains in this protein, whereas the N-terminal zinc-binding domain (residues 3–7) remains intact. In histatins 3 and 5, the single HEKHH site is destroyed in some but not all of the proteolytic attacks. For example, in fragments His3 1/22 and His5 14/24 the zinc-binding motif is intact, whereas in His3 1/17 and His5 1/17, the motif has been abolished. The temporal appearance and disappearance of such peptides may thus be critical for MMP inhibition in the oral cavity.

With regard to the antifungal domains in histatins, the first targeted amino acid in histatin 3, R25, is not affecting the antifungal protein regions, which are located more N terminally. In fact, all histatin 3 fragments appearing in the early peaks, P5–P8 (His3 1/17, His3 1/18, His3 1/22, His3 1/24, and His3 1/25), are expected to display antifungal activity. Likewise, the major histatin 5 fragments detected in peaks P8 and P10 (His5 1/16, His5 1/17, and His5 1/18), contain the antifungal domains. Consistent with this finding, we demonstrated that in the early phases of histatin 5 degradation in WSS the antifungal activity toward Candida albicans is retained (7), supporting the notion that proteolysis is not necessarily instantaneously detrimental for biological activities of histatins directed toward this pathogenic microorganism.

Recent reports indicated that histatin 1 and histatin 3 facilitate wound closure in vitro by stimulating cell migration (24). The authors isolated a histatin 1 fragment from PS with wound closure activity comprising amino acids 14–38. In the present study we demonstrate that this C-terminal 25-residue segment of histatin 1 (His1 14/38), resulting from cleavage after K13, is among the first major fragments generated from histatin 1. The second primary cleavage site in histatin 1 occurred at K17, producing peptide His1 18/38. Both the 14/38 and 18/38 fragments are ultimately further degraded, yielding the 12-residue C-terminal peptide YGDYGSNYLYDN (His1 27/38; eluting in peak 3). The N-terminal fragments of histatin 3 were 25 residues or shorter, which, based on the inactivity of histatin 5, are not expected to display wound-healing properties. The C-terminal peptides from histatin 3 were no shorter than 7 amino acids in length. Thus, in both histatin 1 and 3 proteolytic pathways, the domain essential for wound healing, spanning the C-terminal 7 residues, is uncleaved. The actual wound-healing capacity of this short fragment alone remains to be established.

Overall, proteases and other enzymes operating efficiently in the oral cavity are responsible for the dynamic composition of the WS proteome (33). It is speculated that much of the host protection may actually be attributed to fragments derived from proteins originally synthesized by the glands. The elucidation of salivary protein degradation pathways in WSS will not only be invaluable for biomimetic approaches but also facilitate the selection of peptides for further functional analysis and enable the design of variants that are more protease-resistant and display increased retention times and bioactivity in the oral environment.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grants DE05672, DE07652, DE18448, DE18132, and DE16699.

References

- Lopez-Otin C, Matrisian L M. Emerging roles of proteases in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:800–808. doi: 10.1038/nrc2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall C M, Blobel C P. In search of partners: linking extracellular proteases to substrates. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:245–257. doi: 10.1038/nrm2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudney J D. Does variability in salivary protein concentrations influence oral microbial ecology and oral health? Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1995;6:343–367. doi: 10.1177/10454411950060040501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Slots J. Salivary enzymes. Origin and relationship to periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 1983;18:559–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1983.tb00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Ohata N, Morishita M, Iwamoto Y. Correlation between the protease activities and the number of epithelial cells in human saliva. J Dent Res. 1981;60:1039–1044. doi: 10.1177/00220345810600060601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germaine G R, Tellefson L M, Johnson G L. Whole saliva proteases: development of methods for determination of origins. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1978;107:849–858. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-3369-2_95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmerhorst E J, Alagl A S, Siqueira W L, Oppenheim F G. Oral fluid proteolytic effects on histatin 5 structure and function. Arch Oral Biol. 2006;51:1061–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagnola M, Inzitari R, Rossetti D V, Olmi C, Cabras T, Piras V, Nicolussi P, Sanna M T, Pellegrini M, Giardina B, Messana I. A cascade of 24 histatins (histatin 3 fragments) in human saliva: suggestions for a pre-secretory sequential cleavage pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41436–41443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmerhorst E J, Sun X, Salih E, Oppenheim F G. Identification of Lys-Pro-Gln as a novel cleavage site specificity of saliva-associated proteases. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19957–19966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708282200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messana I, Cabras T, Pisano E, Sanna M T, Olianas A, Manconi B, Pellegrini M, Paludetti G, Scarano E, Fiorita A, Agostino S, Contucci A M, Calo L, Picciotti P M, Manni A, Bennick A, Vitali A, Fanali C, Inzitari R, Castagnola M. Trafficking and postsecretory events responsible for the formation of secreted human salivary peptides: a proteomics approach. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:911–926. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700501-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitorino R, Lobo M J, Duarte J A, Ferrer-Correia A J, Domingues P M, Amado F M. Analysis of salivary peptides using HPLC-electrospray mass spectrometry. Biomed Chromatogr. 2004;18:570–575. doi: 10.1002/bmc.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim F G, Yang Y C, Diamond R D, Hyslop D, Offner G D, Troxler R F. The primary structure and functional characterization of the neutral histidine-rich polypeptide from human parotid secretion. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:1177–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan J, McKnight C J, Troxler R F, Oppenheim F G. Zinc and copper bind to unique sites of histatin 5. FEBS Lett. 2001;491:76–80. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melino S, Gallo M, Trotta E, Mondello F, Paci M, Petruzzelli R. Metal-binding and nuclease activity of an antimicrobial peptide analogue of the salivary histatin 5. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15373–15383. doi: 10.1021/bi0615137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melino S, Rufini S, Sette M, Morero R, Grottesi A, Paci M, Petruzzelli R. Zn2+ ions selectively induce antimicrobial salivary peptide histatin-5 to fuse negatively charged vesicles. Identification and characterization of a zinc-binding motif present in the functional domain. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9626–9633. doi: 10.1021/bi990212c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusman H, Lendenmann U, Grogan J, Troxler R F, Oppenheim F G. Is salivary histatin 5 a metallopeptide? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1545:86–95. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00265-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman A. Taste for zinc. Lancet. 1996;348:1592. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusman H, Travis J, Helmerhorst E J, Potempa J, Troxler R F, Oppenheim F G. Salivary histatin 5 is an inhibitor of both host and bacterial enzymes implicated in periodontal disease. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1402–1408. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1402-1408.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim F G, Xu T, McMillian F M, Levitz S M, Diamond R D, Offner G D, Troxler R F. Histatins, a novel family of histidine-rich proteins in human parotid secretion: isolation, characterization, primary structure, and fungistatic effects on Candida albicans. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:7472–7477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amerongen A V, Veerman E C. Saliva—the defender of the oral cavity. Oral Dis. 2002;8:12–22. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.1o816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Levitz S M, Diamond R D, Oppenheim F G. Anticandidal activity of major human salivary histatins. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2549–2554. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2549-2554.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein D M, Helmerhorst E J, Spacciapoli P, Oppenheim F G, Friden P. Histatin-derived peptides: potential agents to treat localised infections. Exp Opin Emerg Drugs. 2002;7:47–59. doi: 10.1517/14728214.7.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein D M, Spacciapoli P, Tran L T, Xu T, Roberts F D, Dalla Serra M, Buxton D K, Oppenheim F G, Friden P. Anticandida activity is retained in P-113, a 12-amino-acid fragment of histatin 5. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1367–1373. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.5.1367-1373.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oudhoff M J, Bolscher J G, Nazmi K, Kalay H, van 't Hof W, Amerongen A V, Veerman E C. Histatins are the major wound-closure stimulating factors in human saliva as identified in a cell culture assay. FASEB J. 2008;22:3805–3812. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-112003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum B J, Bird J L, Longton R W. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of human salivary histidine-rich-polypeptides. J Dent Res. 1977;56:1115–1118. doi: 10.1177/00220345770560091801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora B, Gusman H, Helmerhorst E J, Troxler R F, Oppenheim F G. A new method for the isolation of histatins 1, 3, and 5 from parotid secretion using zinc precipitation. Protein Expr Purif. 2001;23:198–206. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne J B, Iacono V J, Crawford I T, Lepre B M, Bernzweig E, Grossbard B L. Selective effects of histidine-rich polypeptides on the aggregation and viability of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1991;6:169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1991.tb00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum B J, Bird J L, Millar D B, Longton R W. Studies on histidine-rich polypeptides from human parotid saliva. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1976;177:427–436. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(76)90455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes C. How much saliva is enough for avoidance of xerostomia? Caries Res. 2004;38:236–240. doi: 10.1159/000077760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusman H, Leone C, Helmerhorst E J, Nunn M, Flora B, Troxler R F, Oppenheim F G. Human salivary gland-specific daily variations in histatin concentrations determined by a novel quantitation technique. Arch Oral Biol. 2004;49:11–22. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(03)00182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campese M, Sun X, Bosch J A, Oppenheim F G, Helmerhorst E J. Concentration and fate of histatins and acidic proline-rich proteins in the oral environment [E-pub ahead of print] Arch Oral Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.11.010. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitorino R, Lobo M J, Ferrer-Correira A J, Dubin J R, Tomer K B, Domingues P M, Amado F M. Identification of human whole saliva protein components using proteomics. Proteomics. 2004;4:1109–1115. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmerhorst E J, Oppenheim F G. Saliva: a dynamic proteome. J Dent Res. 2007;86:680–693. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer D, Hunter H, Lajoie G. NMR studies of the antimicrobial salivary peptides histatin 3 and histatin 5 in aqueous and nonaqueous solutions. Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;76:247–256. doi: 10.1139/bcb-76-2-3-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno L S, Li X, Wang L, Soares R V, Siqueira C C, Oppenheim F G, Troxler R F, Offner G D. Two-hybrid analysis of human salivary mucin MUC7 interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iontcheva I, Oppenheim F G, Offner G D, Troxler R F. Molecular mapping of statherin- and histatin-binding domains in human salivary mucin MG1 (MUC5B) by the yeast two-hybrid system. J Dent Res. 2000;79:732–739. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790020601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitorino R, Calheiros-Lobo M J, Williams J, Ferrer-Correia A J, Tomer K B, Duarte J A, Domingues P M, Amado F M. Peptidomic analysis of human acquired enamel pellicle. Biomed Chromatogr. 2007;21:1107–1117. doi: 10.1002/bmc.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Helmerhorst E J, Troxler R F, Oppenheim F G. Identification of in vivo pellicle constituents by analysis of serum immune responses. J Dent Res. 2004;83:60–64. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong W G. Origin and nature of the acquired pellicle. Proc R Soc Med. 1968;61:923–930. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahradnik R T, Moreno E C, Burke E J. Effect of salivary pellicle on enamel subsurface demineralization in vitro. J Dent Res. 1976;55:664–670. doi: 10.1177/00220345760550042101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorsa T, Tjaderhane L, Salo T. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in oral diseases. Oral Dis. 2004;10:311–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2004.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Salih E, Oppenheim F G, Helmerhorst E J. Activity-based mass spectrographic characterization of proteases and inhibitors in human saliva. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2009 doi: 10.1002/prca.200800242. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]