Abstract

The total synthesis of (−)-5-epi-vibsanin E (2) has been achieved in 18 steps. The synthesis combines the rhodium-catalyzed [4 + 3] cycloaddition between a vinylcarbenoid and a diene to rapidly generate the tricyclic core with an effective end game strategy to introduce the remaining side-chains. The [4 + 3] cycloaddition occurs by a cyclopropanation to form a divinylcyclopropane followed by a Cope rearrangement to form a cycloheptadiene. The quaternary stereogenic center generated in the process can be obtained with high asymmetric induction when the reaction is catalyzed by the chiral dirhodium complex, Rh2(S-PTAD)4.

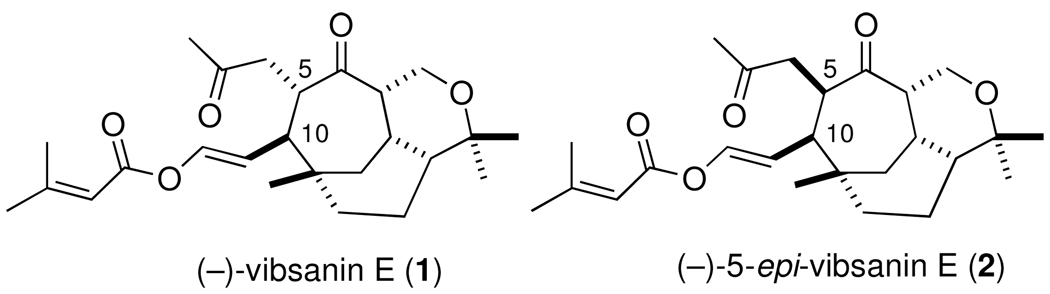

Two striking examples of highly functionalized cycloheptane natural products are (−)-vibsanin E (1) and (−)-5-epi-vibsanin E (2), each containing five stereogenic centers within the cycloheptane ring. Vibsanin E (1) was first isolated by Kawazu from the Japanese fish poison plant Viburnum odoratissimum (Sangoju) in 1978,1 whereas 5-epi-vibsanin E (2) was isolated 24 years later by Fukuyama from Viburnum awabuki (Caplifoliaceae).2 Several synthetic approaches to these targets have been reported,3 a number of which have resulted in the formation of stereoisomers of 1 and 2. Their total syntheses, however, has remained elusive. This paper will describe the application of the [4 + 3] cycloaddition between vinylcarbenoids and dienes to the asymmetric synthesis of (−)-5-epi-vibsanin E (2). The synthetic approach is a collaborative effort exploiting the vinylcarbenoid chemistry developed by the Davies group4 and the end-game synthetic strategies devised by the Williams group.5

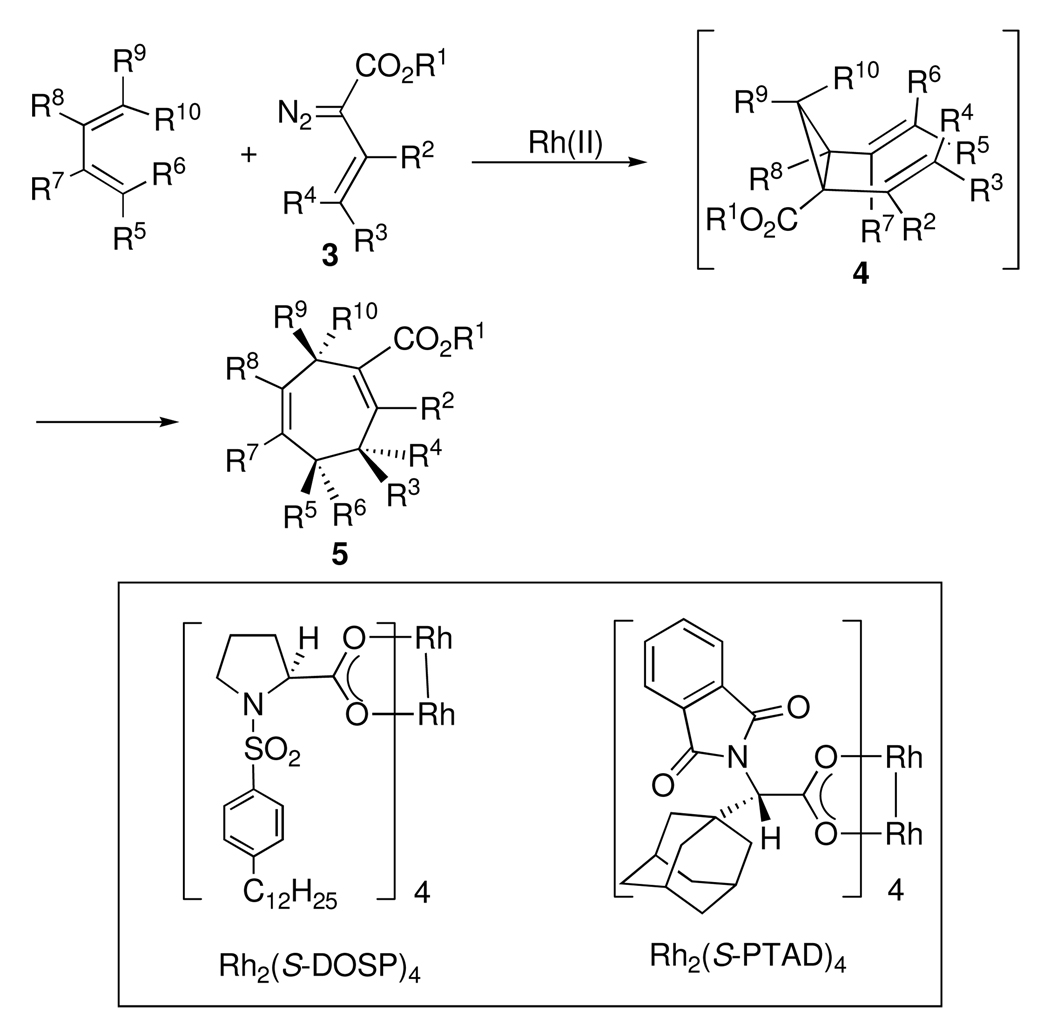

The Davies group has developed a general method for the stereoselective construction of seven-membered rings 5 by means of a formal [4 + 3] cycloaddition between vinyldiazoacetates 3 and dienes (Scheme 1).4 The reaction proceeds via a cyclopropanation to form divinylcyclopropanes 4, which undergo a Cope rearrangement to form 5 with excellent stereocontrol. The reaction occurs with a range of substrates and in selected systems, highly enantioselective reactions are possible. The dirhodium tetraprolinate catalyst Rh2(S-DOSP)4 gives high asymmetric induction in the [4 + 3] cycloaddition providing that R1 in the vinyldiazoacetate 3 is a methyl ester, R3 is alkyl or aryl, and R2 and R4 are unfunctionalized. 4b Recently, Rh2(S-PTAD)4 has been shown to be an effective chiral catalyst for the synthesis of tropanes by a [4 + 3] cycloaddition between 3-siloxy-2-diazobutenoate and N-Bocpyrroles, 4c and hence was predicted to be effective for this system.

Scheme 1.

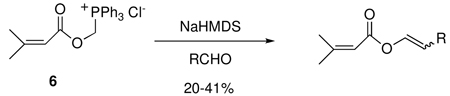

One of the most challenging problems in the late stage strategy for the synthesis of seven membered ring vibsanins is the synthesis of the (E)-vinylacetate functionality,3c which is present in the C-10 side chain of 1 and 2. The Williams group has developed an effective method to solve this problem by means of a Wittig reaction with ylide 6 as illustrated in eq 1.5

|

(1) |

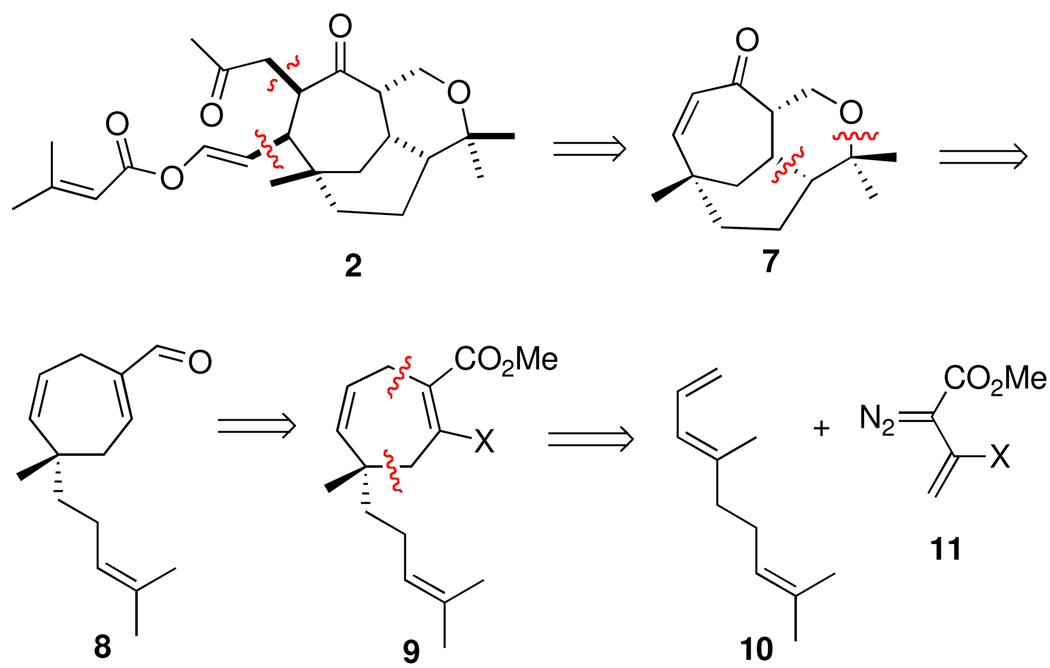

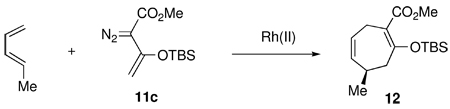

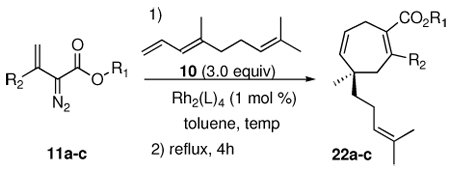

Based on the above facets, the proposed retrosynthetic approach to 2, shown in Scheme 2, exploits the synthetic methods developed by the two groups. The side chain functionality was anticipated to be introduced into the tricyclic core 7 using cuprate conjugate addition followed by alkylation of the resulting enolate. The tricyclic core had been previously generated in racemic form by an intramolecular hetero-Diels-Alder reaction from the enal 8.3c The cycloheptadiene ring in 9 was readily generated from a [4 + 3] cycloaddition between the diene 10 and the vinyldiazoacetate 11a (X = H).3c However, to apply this synthetic approach to the enantioselective synthesis of the natural product target, the initial [4 + 3] cycloaddition would need to be conducted in an enantioselective manner. Once the quaternary stereogenic center in 9 has been set, the control of the remaining stereocenters should be relatively straightforward. Preliminary studies on Rh2(S-DOSP)4-catalyzed cycloaddition with the vinyldiazoacetate 11a (X = H) were not very promising, as the highest enantioselectivity that could be obtained in this type of cycloaddition was only 63% ee.3c If the enantioselective [4 + 3] cycloaddition between 3-siloxy-2-diazobutenoate 11c (X = OTBS) and pyrroles4c could be extended to regular dienes, then this could be an acceptable solution for an asymmetric entry into the necessary cycloheptadiene systems. Therefore, the first stage of this investigation was to determine the scope of this enantioselective transformation with model dienes.

Scheme 2.

The reaction of 3-siloxy-2-diazobutenoate 11c with trans-piperylene was used to optimize the conditions for the [4 + 3] cycloadditions (Table 1). The Rh2(S-DOSP)4 catalyzed reaction at room temperature, generated the desired product 12 in high yield but with poor enantioselectivity (38% ee). The enantioselectivity of 12 could be improved to 53% ee by conducting the reaction at −26 °C but under these conditions the yield dropped to 35%. In contrast, the Rh2(S-PTAD)4 catalyzed reaction at room temperature gave 12 in 78% yield and 86% ee. At −26 °C, the enantioselectivity improved to 95% ee and the yield was 88%. As previously observed in the Rh2(S-PTAD)4 and Rh2(S-DOSP)4 catalyzed reactions of 11c,4c both catalysts preferentially form the same enantiomer.

Table 1.

Optimization of the enantioselective [4 + 3] cycloaddition

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rh(II) | temp (°C) | yield(%) | ee (%) |

| Rh2(S-DOSP)4 | 23 | 85 | 38 |

| Rh2(S-DOSP)4 | −26 | 35 | 53 |

| Rh2(S-PTAD)4 | 23 | 78 | 86 |

| Rh2(S-PTAD)4 | −26 | 88 | 95 |

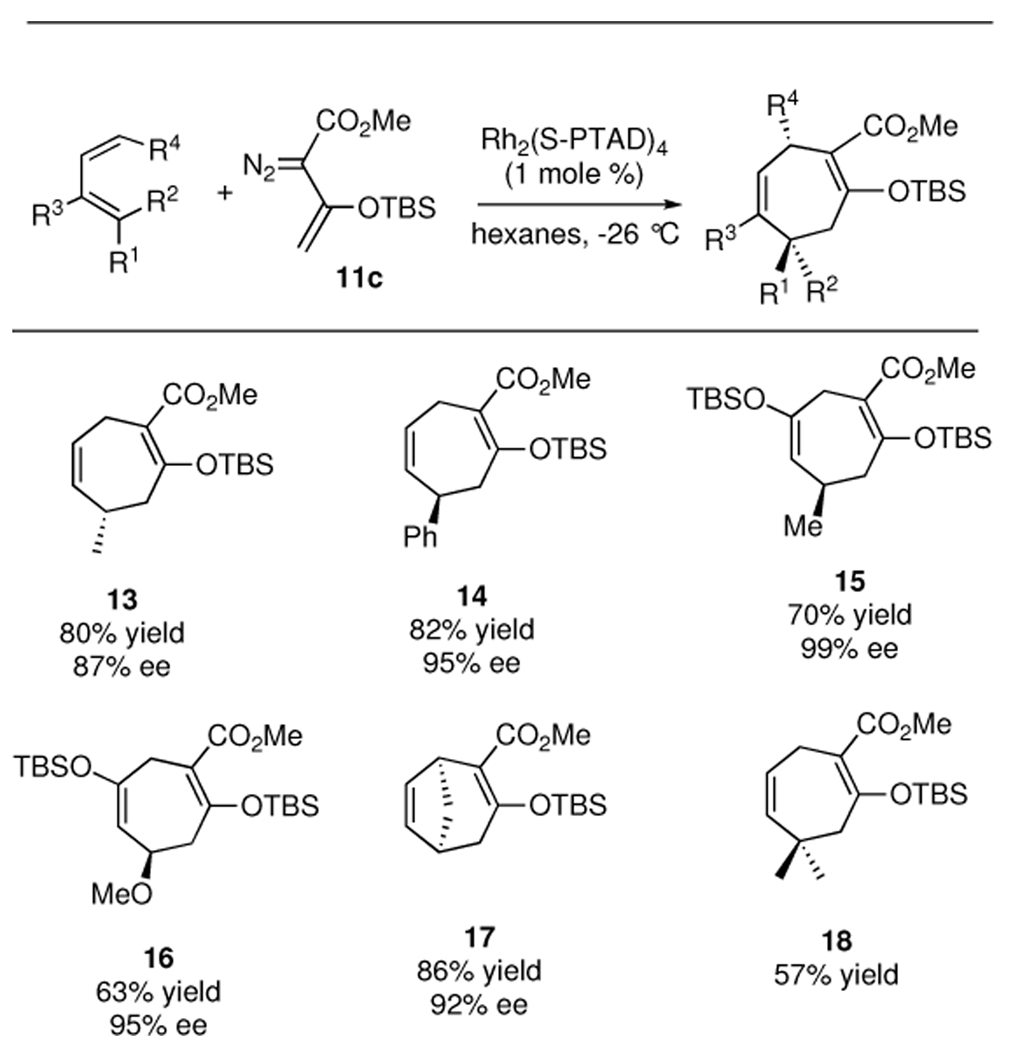

The Rh2(S-PTAD)4 catalyzed reactions of 11c could be conducted with a variety of dienes and the results are summarized in Table 3. In all the systems tested, the cycloadducts are formed in good yields (57–86%) and with high enantioselectivities (87–98% ee). The reaction with cis-piperylene generates the cycloheptadiene 13, the opposite enantiomer to the product generated from transpiperylene. Even though the cycloadduct 18, from reaction with 4-methyl-1,3-pentadiene, is not chiral, a successful reaction with this substrate was of importance for this endeavor, as a 4-substituted-1,3-diene was required for total synthesis studies (see table 3 below).

Table 3.

Enantioselective [4 + 3] cycloadditions with diene 10

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Rh2(L)4 | R1 | R2 | temp (°C) | product | yield (%) | ee (%) |

| 1 | Rh2(S-DOSP)4 | CH3 | H | rt | 22a | 62 | 50 |

| 2 | Rh2(S-PTAD)4 | CH3 | H | rt | 22a | 67 | 40 |

| 3 | Rh2(S-DOSP)4 | t-Bu | H | rt | 22b | 60 | 5 |

| 4 | Rh2(S-PTAD)4 | t-Bu | H | rt | 22b | 63 | 57 |

| 5 | Rh2(S-DOSP)4 | CH3 | OTBS | −78 to rt | 22c | 55 | 45 |

| 6 | Rh2(S-PTAD)4 | CH3 | OTBS | −20 to −15 | 22c | 55 | 91 |

| 7 | Rh2(S-PTAD)4 | CH3 | OTBS | −10 | 22c | 67 | 90 |

| 8 | Rh2(S-PTAD)4 | CH3 | OTBS | 0 to 5 | 22c | 70 | 87 |

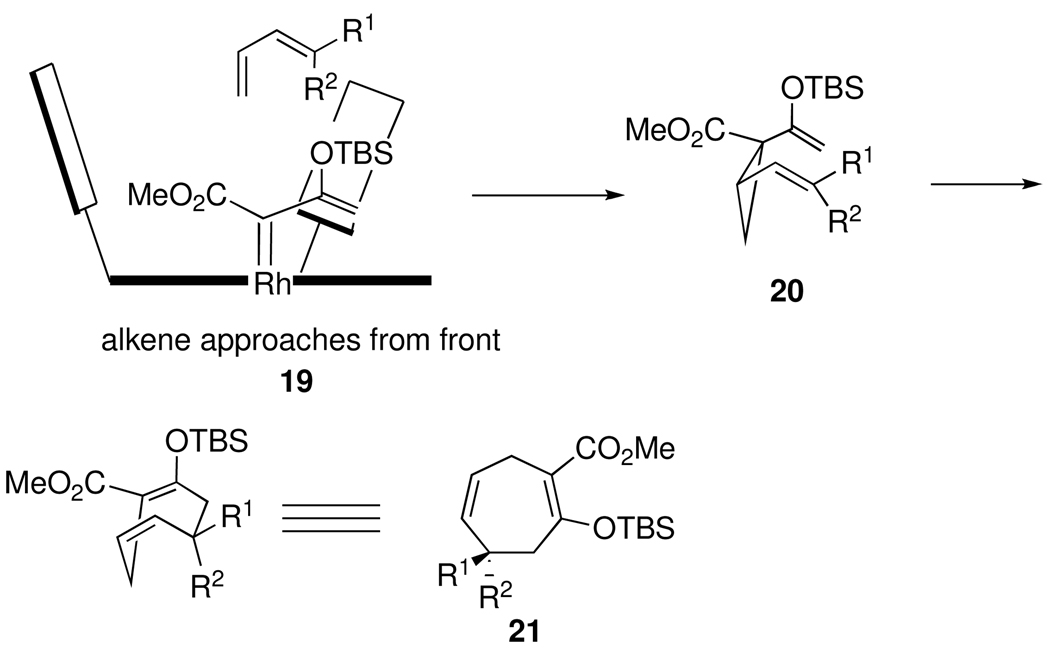

The absolute configuration of the products 12–17 has been assigned using the predictive model for cyclopropanation with donor/acceptor carbenoids3b,6 combined with the catalyst model developed by Hashimoto7 for related phthalimido carboxylate rhodium catalysts. This model correctly predicted the absolute configuration of the [4 + 3] cycloadducts from the Rh2(S-PTAD)4 catalyzed reactions of 3-siloxy-2-diazobutenoate 11c with pyrroles.4c In the model shown in Scheme 3, the vinylcarbenoid in the complex 19 aligns with the bulky group (OTBS) away from the phthalimido groups. The diene approaches from the front face to generate the divinylcyclopropane 20, which then undergoes the Cope rearrangement through a boat transition state to form 21. Evidence to confirm the accuracy of the predictive model was obtained by conversion of the cycloheptadiene 14 to (S)-phenylsuccinic acid by an oxidative ozonolysis of the two double bonds in 14.4b

Scheme 3.

Our focus then turned to the examination of the [4 + 3] cycloaddition with the actual diene 10 required for the total synthesis (Table 3). Earlier studies6c had shown that the Rh2(S-DOSP)4-catalyzed reaction of 10 with the vinyldiazoacetate 11a did not give the cycloheptadiene 22a with high asymmetric induction. A similar reaction of 11a catalyzed by Rh2(S-PTAD)4 failed to enhance the enantioselectivity (entry 2). Altering the methyl ester to a tert-butyl ester as in 11b had a considerable effect on the enantioselectivity. The reaction of 11b with 10 catalyzed by Rh2(S-DOSP)4 gave 22b in only 5% ee (entry 3), whereas the Rh2(S-PTAD)4 catalyzed reaction gave 22b in 57% ee (entry 4). Significantly better results were obtained with the siloxyvinyldiazoacetate 11c. Even though the Rh2(S-DOSP)4 catalyzed reaction of 11c gave the [4 + 3] cycloadduct 22c with only moderate enantioselectivity (45% ee, entry 5), the Rh2(S-PTAD)4 catalyzed reaction gave 22c in 67% yield and 90% ee (entry 7). This asymmetric transformation sets up the crucial quaternary stereogenic center required to control the remaining stereocenters in the synthesis.

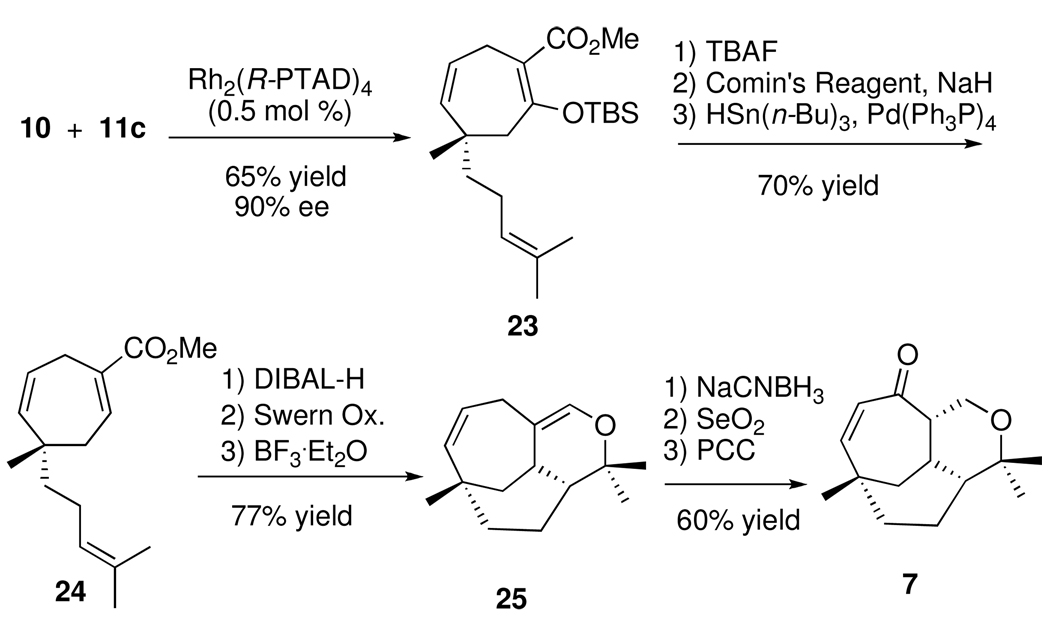

The model studies showed that an enantioselective [4 + 3] cycloaddition is a viable approach for the total synthesis of either (−)-vibsanin E (1) and/or (−)-5-epi-vibsanin E (2). The predictive model (Scheme 4) indicates that the enantiomeric catalyst Rh2(R-PTAD)4 will be required in the key reaction. The [4 + 3] cycloaddition between diene 10 and 11c could be conveniently conducted on a ten gram scale with Rh2(R-PTAD)4 loading as low as 0.5 mol % to generate the cycloheptadiene 23 in 67% yield with 90% ee. The siloxy group in 23 was removed and the resulting enol was converted to the triflate, and then reduced under palladium-catalyzed conditions to form 24. The generation of the tricyclic core 7 from 24 was achieved using a similar sequence to the one that had been previously used in the racemic series.3c Conversion of the unsaturated ester in 24 to the aldehyde followed by a Lewis-acid catalyzed hetero-Diels-Alder reaction generated the tricycle 25 in 77% overall yield. Reduction of the enol ether in 25 under acidic conditions followed by allylic oxidation generated the key tricyclic enone 7. This material could be enriched by a single recrystallization from hexanes (75% recovery) or by preparative HPLC using a chiral stationary phase.

Scheme 4.

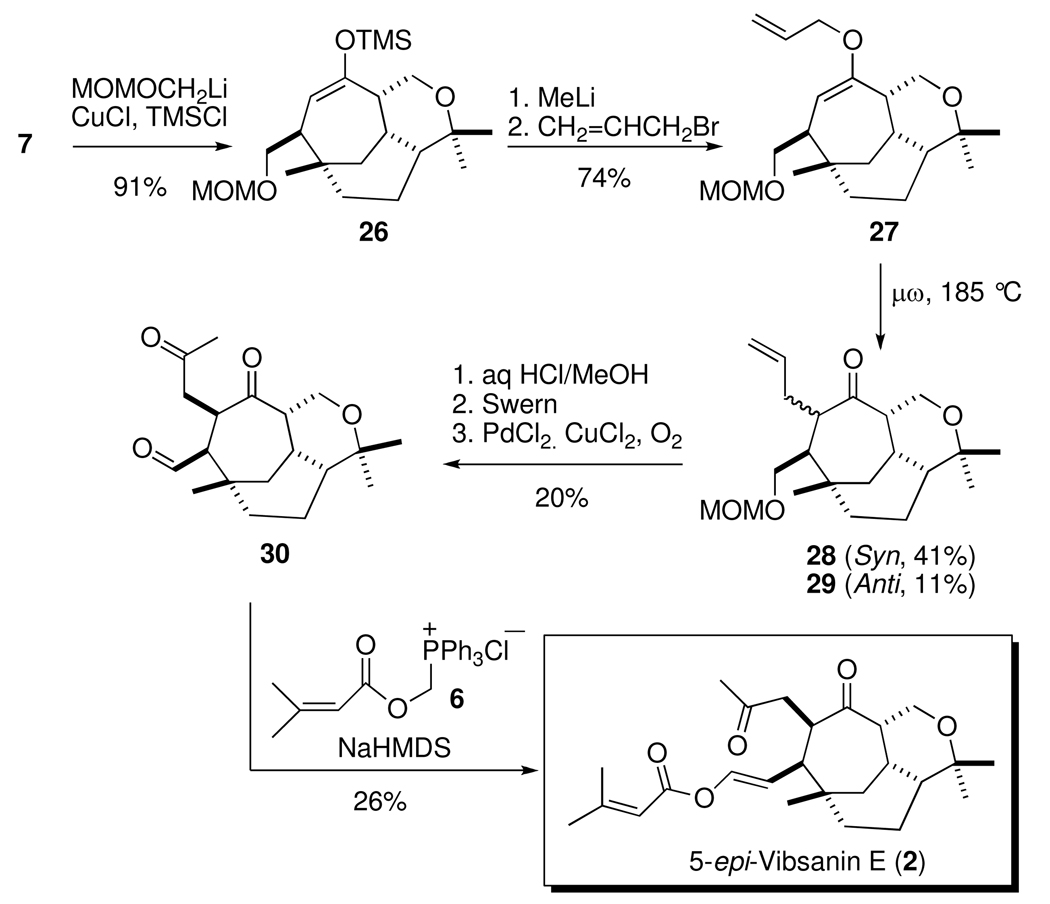

Much of the previous difficulties encountered with the synthesis of 1 and 2 arose due to complications with introduction of the side chains.3 An obvious solution to these problems, starting from bicycle 7, was utilization of tandem conjugate addition/alkylation chemistry. However, the most applicable reagents (vinyl, allyl, etc.) failed to undergo the 1,4-addition, presumably due to the presence of the sterically crowded quaternary center at the γ-position. The only reported successful conjugated addition to 7 occurred for a methyl group, which did generate the desired 10-β stereochemistry.3c These results led to the expectation that only a highly electron rich cuprate would facilitate the conjugate addition, but the only functionalized system fitting this criterion are the α-oxa methylene anions (i.e. MOMOCH2Li derived from MOMOCH2SnBu3).8 Initial attempts to drive the 1,4-addition failed; however, addition of the activator, TMSCl,9 promoted the reaction with the desired regiochemistry of the silyl enol ether 26 in excellent yield (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Attempts to trap the in situ enolate, derived from the cuprate addition with various allyl electrophiles failed. Treatment of 26 with methyl lithium to generate the desired regioisomer of the enolate followed by quenching with allyl bromide afforded the O-allylated material 27 in 74% yield. This reaction was very effective at relatively small scale [0.6 mmol (26)], but upon scale-up, significant amounts of the undesired bridgehead C-allylated material was formed, which was also observed in the subsequent Clasien rearrangement below. Microwave promoted Claisen rearrangement of 27 afforded the syn- and anti-isomeric products, 28 (41%) and 29 (11%), respectively. Acetal deprotection proceeded when gently heated in aqueous methanolic acid, albeit with slight epimerization. Swern oxidation and subsequent Wacker oxidation afforded the diketoaldehyde 30 in 20% yield over three steps. Treatment of 30 with ylide 6,5 the Anders-Gaβner variant on the Wittig reaction,10 produced 5-epi-vibsanin E (2)11 in 26% yield (Scheme 5).

In conclusion, considerable effort has been exerted in the pursuit of natural products containing densely functionalized fused seven-membered rings (e.g. the guanacastepenes).12 The challenges associated with such synthetic campaigns has been a driving force for the development of a number of new synthetic strategies, The total synthesis of 5-epi-vibsanin E (2), efficiently synthesized in 18 steps, is a further exemplar to this cause, in that, the synthesis combines asymmetric rhodium-catalyzed [4 + 3] cycloaddition methodology to rapidly generate the tricyclic core paving the road for an effective end game strategy to introduce the remaining side-chains.

Supplementary Material

Full experimental and characterization data for the new compounds described in this paper along with copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra.

Figure 1.

Table 2.

[4 + 3] Cycloadditions between 11c and dienes

|

Acknowledgement

We thank the University of Queensland, University at Buffalo, Australian Research Council (DP0666855) and the National Institutes of Health (GM080337) for financial support. Prof. Fukuyama from the Tokushima Bunri University (Japan) is gratefully acknowledged for providing NMR spectra of natural 5-epi-vibsanin E (2). The University of Queensland, Enantioselective Chromatography Facility is acknowledged for assistance with ee determinations and preparative separations. HMLD has financial interests in Dirhodium Technologies, Inc., a company that manufactures chiral dirhodium catalysts.

References

- 1.(a) Kawazu K. IUPAC Int. Symp. Chem. Nat. Prod. (11th) 1978;2:101. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kawazu K. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1980;44:1367. [Google Scholar]; (c) Fukuyama K, Katsube Y, Kawazu K. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. II. 1980:1701. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukuyama Y, Minami H, Matsuo A, Kitamura K, Akizuki M, Kubo M, Kodama M. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002;50:368. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Heim R, Wiedemann S, Williams CM, Bernhardt PV. Org. Lett. 2005;7:1327. doi: 10.1021/ol0501222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schwartz BD, Tilly DP, Heim R, Wiedemann S, Williams CM, Bernhardt PV. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006:3181. [Google Scholar]; (c) Davies HML, Loe Ø, Stafford DG. Org. Lett. 2005;7:5561. doi: 10.1021/ol052005c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Nikolai J, Loe Ø, Dominiak PM, Gerlitz OO, Autschbach J, Davies HML. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10763. doi: 10.1021/ja072090e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Schwartz BD, Williams CM, Bernhardt PV. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2008;4(No 34) doi: 10.3762/bjoc.4.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Davies HML. In: Advances in Cycloaddition. Harmata M, editor. Vol. 5. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1998. pp. 119–164. [Google Scholar]; (b) Davies HML, Stafford DG, Doan BD, Houser JH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:3326. [Google Scholar]; (c) Reddy RP, Davies HML. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10312. doi: 10.1021/ja072936e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz BD, Williams CM, Anders E, Bernhardt PV. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:6482. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nowlan DT, Gregg TM, Davies HML, Singleton DA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:15902. doi: 10.1021/ja036025q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Takahashi T, Tsutsui H, Tamura M, Kitagaki S, Nakajima M, Hashimoto S. Chem. Commun. 2001:1604. doi: 10.1039/b103747c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Minami K, Saito H, Tsutsui H, Nambu H, Anada M, Hashimoto S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2005;347:1483. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linderman RJ, Godfrey A, Horne K. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:495. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mander LN, Thomson RJ. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:1654. doi: 10.1021/jo048199b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Anders E, Gassner T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1982;21:289. [Google Scholar]; (b) Anders E, Gassner T. Angew. Chem. Suppl. 1982:675. [Google Scholar]; (c) Anders E, Gassner T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1983;22:619. [Google Scholar]

- 11.1H and 13C NMR spectra are an identical match to the spectra of 5-epi-vibsanin E (2) derived from natural sources. See supporting information.

- 12.Danishefsky SJ. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:10619. doi: 10.1021/jo051470k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lin S, Dudley GB, Tan DS, Danishefesky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:2188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shi B, Hawryluk NA, Snider BB. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:1030. doi: 10.1021/jo026702j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Boyer F-D, Hanna I, Ricard L. Org. Lett. 2004;6:1817. doi: 10.1021/ol049452x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Mehta G, Pallavi K, Umarye JD. Chem. Commun. 2005:4456. doi: 10.1039/b506931a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Miller AK, Hughes CC, Kennedy-Smith JJ, Gradl SN, Trauner D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:17057. doi: 10.1021/ja0660507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Limura S, Overman LE, Paulini R, Zakarian A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13095. doi: 10.1021/ja0650504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Magnus P, Ollivier C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:9605. [Google Scholar]; (i) Chiu P, Li S. Org. Lett. 2004;6:613. doi: 10.1021/ol036433z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Shipe WD, Sorensen EJ. Org. Lett. 2002;4:2063. doi: 10.1021/ol0259342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Hughes CC, Miller AK, Trauner D. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3425. doi: 10.1021/ol047387l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Du X, Chu HV, Kwon O. Org. Lett. 2003;5:1923. doi: 10.1021/ol0344873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Li C-C, Liang S, Zhang X-H, Xie Z-X, Chen J-H, Wu Y-D, Yang Z. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3709. doi: 10.1021/ol051312f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Brummond KM, Gao D. Org. Lett. 2003;5:3491. doi: 10.1021/ol035322x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Full experimental and characterization data for the new compounds described in this paper along with copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra.