Abstract

Background

Given the improved survival of patients after acute myocardial infarction (AMI), a greater number of patients are at risk for cerebrovascular complications of AMI. Trends in the magnitude of stroke in the setting of AMI are not well characterized, however, nor have contemporary trends in the hospital death rates of patients developing acute stroke been examined.

Methods and Results

Among 9,220 patients without a history of stroke hospitalized with confirmed AMI between 1986 and 2005 in all greater Worcester (MA) medical centers, 132 patients (1.4%) experienced an acute stroke during hospitalization. The proportion of patients with AMI who developed a stroke increased through the 1980’s and 1990’s but declined slightly thereafter. Advanced age, female gender, history of a previous MI, and occurrence of atrial fibrillation during hospitalization were associated with a greater risk of stroke. Receipt of a percutaneous coronary intervention during hospitalization was associated with a lower risk of stroke. Compared to patients who did not experience a stroke, patients developing a stroke in the 1990’s were approximately three times as likely to die during hospitalization (OR = 2.91; 95% CI = 1.72, 5.19) whereas those experiencing a stroke in the 2000’s were five times as likely to die (OR = 5.36; 95% CI = 2.71, 10.64).

Conclusions

While the incidence rates of stroke complicating AMI have declined somewhat since 1999, there is not a corresponding decline in the odds of dying during hospitalization in those developing a stroke. Although contemporary therapies may be reducing the risk of stroke in patients with AMI, more attention should be directed to improving the short-term prognosis of these high risk patients.

Introduction

Given the improved survival of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) over the past several decades,1 an increasing pool of patients are at risk for serious complications of AMI, including ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. While stroke is a relatively infrequent complication of AMI, with approximately 1–2% of patients with AMI developing a stroke during their index hospitalization,2 the occurrence of stroke in patients with AMI is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.3, 4 In addition, clinical and epidemiologic studies have reported an excess risk of stroke after MI during the 1980’s and 1990’s,5 6 trends coincident with the increasing utilization of thrombolytic therapy for the hospital management of patients with AMI. The risk of in-hospital stroke complicating AMI has not been well characterized, however, particularly during recent periods, nor has the potentially changing association between the occurrence of stroke and hospital death rates.

Using data from a community-wide surveillance study of patients hospitalized with AMI in a large New England community,7–9 we examined 2 decade long trends (1986–2005) in the incidence rates of stroke complicating AMI, patient and treatment characteristics associated with the occurrence of stroke, and the impact of stroke on hospital mortality. The study population consisted of 9,220 residents of the Worcester, Massachusetts, metropolitan area hospitalized with AMI at all greater Worcester medical centers in 11 annual periods between 1986 and 2005.

Methods

Data for this study were derived from the Worcester Heart Attack Study. This is an ongoing population-based investigation that is examining long-term trends in the incidence, hospital, and post-discharge case-fatality rates of AMI among residents of the Worcester metropolitan area hospitalized at all 16 greater Worcester medical centers.7–10 Fewer hospitals (n=11) have been included during recent study years due to hospital closures, mergers, and conversion to chronic care facilities. The details of this study have been described previously.8, 9 In brief, the medical records of residents of the Worcester metropolitan area (2000 census estimate = 478,000) hospitalized for possible AMI at all greater Worcester medical centers were individually reviewed and a diagnosis of AMI was validated according to predefined criteria.8, 9 Patients who developed AMI secondary to an interventional procedure or surgery were excluded from the study sample.

Because we were interested in examining changing trends in the magnitude of incident (initial) cases of stroke, patients with a history of stroke (n=1,103) were excluded from the present study. The percentage of AMI patients with a history of stroke increased slightly over the period under study; in the 1980’s, 9.0% (n=273) of our study sample had a history of stroke, 10.8% (n=430) had a history of stroke among those hospitalized with AMI in the 1990’s, and since 2000, 12.1% (n=400) of AMI patients had a history of a previous stroke.

Data Collection

Demographic, medical history, and clinical data were abstracted from the hospital medical records of geographically eligible patients with confirmed AMI by trained study physicians and nurses. Information was collected about patient's age, sex, body mass index, comorbidities (e.g., angina, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, atrial fibrilation), AMI order (initial vs. prior), type (Q wave vs. non–Q wave) and location (anterior vs. inferior/posterior), hospital treatment approaches, and hospital discharge status. Information was collected about the occurrence of clinically significant in-hospital complications including stroke,6 atrial fibrillation,11 heart failure12 and cardiogenic shock.13 The occurrence of acute stroke was defined as the development of neurologic changes consistent with a stroke based on information contained in medical charts and reviewed by a team of nurse and physician abstractors.6 Since 1991, information about the type of stroke (hemorrhagic / ischemic) has been recorded. Information about whether the stroke was confirmed by a neurologist or diagnostic imaging studies was not recorded. Survival status after hospital discharge was ascertained through review of medical records for additional hospitalizations and a statewide and national search of death certificates for residents of the Worcester Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Data Analysis

We examined differences between patients who developed, as compared to those who did not develop, an acute stroke during hospitalization for AMI with respect to their demographic and clinical characteristics, treatment practices, and hospital outcomes through the use of chi-square and t-tests for discrete and continuous variables, respectively. Three logistic regression models were performed to identify variables independently associated with the development of stroke. The first model controlled for age and sex only, the second model included prior comorbidities (history of angina, documented coronary artery disease, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, or hypertension), while the third model included AMI associated characteristics, occurrence of in-hospital complications (development of atrial fibrillation, heart failure, or cardiogenic shock), and information about thrombolytic therapy and hospital procedures (cardiac catheterization, percutaneous coronary intervention, and coronary artery bypass surgery).

Logistic regression analysis was used to examine changes over time in the odds of developing an acute stroke, simultaneously controlling for previously described demographic and clinical factors associated with the risk of stroke. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was also used to examine the association between occurrence of an acute stroke and hospital mortality, using the three model regression approach described previously.

Results

Of the 9,220 patients (mean age = 69 years; 42% female) hospitalized with confirmed AMI at all greater Worcester hospitals without prior stroke during the period under study (1986–2005), 132 patients (1.4%) experienced an acute stroke during hospitalization. Overall, 73% of all strokes occurring between 1991 and 2005 were ischemic. In the 1990’s, approximately three quarters of strokes complicating AMI were ischemic in origin and, since 2000, approximately two thirds of all strokes in the setting of AMI were ischemic (p=0.18).

Factors associated with occurrence of acute stroke

Patients who experienced a stroke were significantly older, more likely to be female, were more likely to have a medical history of atrial fibrillation or a do not resuscitate order, and were more likely to have their hospital stay complicated by atrial fibrillation (Table 1). Patients with stroke were less likely to have undergone cardiac catheterization or a percutaneous coronary intervention.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) according to the development of in-hospital stroke (Worcester Heart Attack Study).

| Stroke | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Present (n=132) |

Absent (n=9,088) |

p-value |

| Age (mean, yrs) | 75.5 | 69.1 | <0.001 |

| Female (%) | 60.6 | 41.9 | <0.001 |

| Medical history (%) | |||

| Angina pectoris | 19.7 | 24.0 | 0.25 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 26.5 | 28.2 | 0.37 |

| Hypertension | 67.4 | 59.6 | 0.07 |

| Heart failure | 22.0 | 18.8 | 0.35 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 16.4 | 9.8 | 0.01 |

| Delay time to hospital (median, hours) | 2.4 | 2.0 | 0.24 |

| Length of hospital stay (median, days) | 6.0 | 8.5 | <0.001 |

| Do not resuscitate order (%) | 46.0 | 19.3 | <0.001 |

| Physiologic findings at admission (mean) | |||

| Hematocrit (%) (n=5540) | 38.7 | 40.2 | <0.01 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) (n=5478) | 188.1 | 182.0 | 0.53 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) (n=5211) | 185.3 | 199.9 | <0.01 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) (n=4407) | 151 | 142 | <.05 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) (n=4258) | 81 | 77 | 0.18 |

| Peak Systolic BP during hospital stay (n=1796) | 173 | 158 | <0.05 |

| Peak Diastolic BP during hospital stay (n=1795) | 95 | 88 | <0.05 |

| Heart rate (bpm) (n=9065) | 93.8 (27.5) | 85.8 (23.9) | <0.01 |

| Estimated Glomerular | 54.4 (25.0) | 62.1 (28.7) | 0.01 |

| Filtration Rate (GFR) (ml/min per 1.73 m2) (n=5506) | |||

| GFR | |||

| ≤30 | 17.2 | 11.0 | |

| 30–59 | 43.0 | 34.6 | |

| ≥ 60 | 39.8 | 54.4 | 0.01 |

| AMI characteristics (%) | |||

| Initial | 59.1 | 67.0 | 0.06 |

| Q-wave | 32.6 | 35.6 | 0.47 |

| Anterior | 28.0 | 27.6 | 0.92 |

| Clinical complications (%) | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 34.8 | 16.7 | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 40.9 | 36.3 | 0.28 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 6.1 | 6.4 | 0.88 |

| Intervention procedures | |||

| Cardiac catherization | 28.0 | 41.4 | p<.01 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 10.6 | 21.0 | p<.01 |

| Coronary artery bypass surgery | 4.6 | 4.7 | 0.94 |

Physiologic data at the time of hospital admission were available in a sub-sample of patients from the mid-1990’s to the most recent year under study. Patients who experienced an acute stroke had lower serum hematocrit findings, total serum cholesterol levels, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) but higher heart rate, systolic blood pressure findings at admission, and higher peak systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels during their hospital stay compared to those without an acute stroke (Table 1).

After adjusting for demographic factors, comorbid conditions, AMI associated characteristics, and clinical complications of AMI, advanced age (≥75 years), female gender, history of a prior MI, and development of atrial fibrillation during hospitalization were associated with a significantly increased odds of acute stroke (Table 2). The odds of stroke were unchanged when thrombolytic therapy and in-hospital interventions were controlled for in our regression analyses. When we controlled for length of hospital stay and use of do not resuscitate orders (DNR), the present results did not change materially. Use of DNR and longer hospital stay were associated with a significantly greater risk of experiencing an acute stroke (DNR: OR = 2.88; 95% CI 1.80, 4.60; Length of stay: OR=1.03; 95% CI 1.03, 1.05)

Table 2.

Factors associated with occurrence of stroke in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (Worcester Heart Attack Study)

| Characteristic* | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | |||

| 55–64 | 0.94 (0.39, 2.23) | 1.16 (0.42, 3.13) | 1.71 (0.80, 3.66) |

| 65–74 | 1.82 (0.88, 3.74) | 2.35 (1.00, 5.51) | 2.43 (1.14, 5.15) |

| ≥75 | 2.81 (1.43, 5.53) | 3.37 (1.49, 7.62) | 2.25 (1.84, 5.98) |

| Female | 1.66 (1.15, 2.39) | 1.92 (1.28, 2.86) | 2.11 (1.24, 3.58) |

| No not resuscitate order | |||

| Length of hospital stay | |||

| Medical history | |||

| Angina pectoris | 0.59 (0.36, 0.96) | 0.82 (0.45, 1.51) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.85 (0.56, 1.30) | 0.87 (0.48, 1.57) | |

| Hypertension | 1.10 (0.72, 1.65) | 1.02 (0.60, 1.77) | |

| Heart failure | 0.77 (0.47, 1.24) | 0.56 (0.28, 1.26) | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.41 (0.84, 2.39) | 1.14 (0.53, 2.45) | |

| AMI characteristics | |||

| Initial | 0.61 (0.41, 0.90) | 0.50 (0.29, 0.86) | |

| Q-wave | 1.19 (0.78, 1.81) | 1.02 (0.57, 1.82) | |

| Anterior | 0.91 (0.58, 1.42) | 1.02 (0.57, 1.79) | |

| Clinical complications | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.52 (1.42, 4.45) | ||

| Heart failure | 0.87 (0.50, 1.51) | ||

| Cardiogenic shock | 1.21 (0.42, 3.48) | ||

| In-hospital thrombolytic therapy | 1.45 (0.75, 2.79) | ||

| Intervention procedures | |||

| Cardiac catheterization | 0.65 (0.30, 1.38) | ||

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 0.91 (0.37, 2.22) | ||

| Coronary artery bypass surgery | 1.53 (0.51, 4.63) |

Respective referent categories = age<55 years, male sex, absence of selected medical history variables, prior AMI, Non-Q-wave AMI, inferior or posterior AMI, absence of selected clinical complications, absence of selected prescribed medications, absence of selected in-hospital therapies and procedures.

Based on previous work indentifying a diastolic BP >90mmHg, as well as GFR and heart rate as factors associated with the risk of stroke,14 we included these physiologic variables in our regression models. The association between age, sex and risk of stroke were attenuated, perhaps due to the inclusion of these variables in the calculation of estimated GFR, whereas the physiologic variables were not significantly associated with the risk of stroke (Compared to eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m3, eGFR <30: OR=2.32; 95%CI = 0.83, 6.45; eGFR 30–59: OR=1.38; 95%CI = 0.62, 3.03) (Diastolic BP > 90 mmHg: OR=1.90; 95%CI = 0.96, 3.76, compared to diastolic BP ≤90 mmHg) (Heart Rate (beats per minute): OR=0.99; 95%CI = 0.98, 1.01).

Time trends in the hospital incidence rates of acute stroke

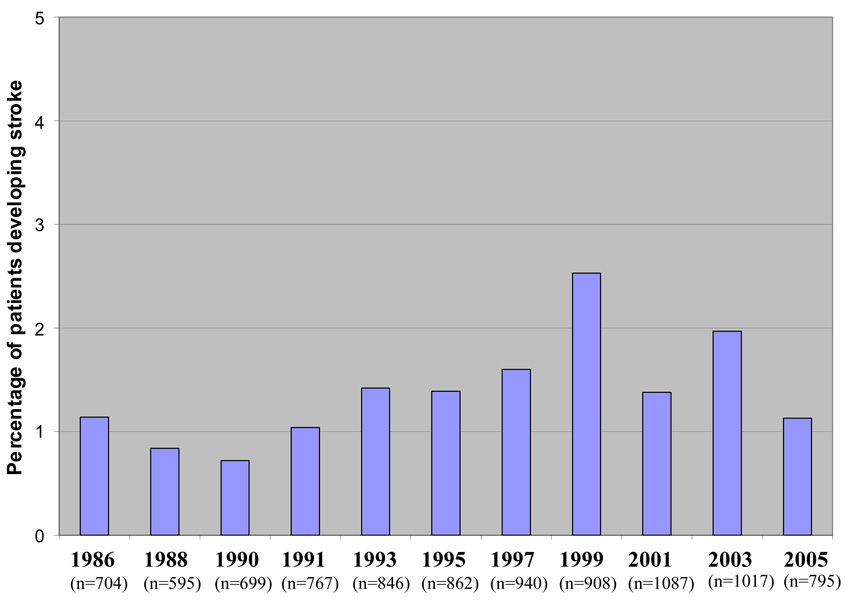

Following declines in the frequency of incident stroke between 1986 and 1990, stroke rates increased through the 1990s peaking in 1999 (Figure 1). Beginning in 2001, stroke rates began to decline slightly with the incidence rate falling to 1.4% in 2005, similar to the rate observed in our initial study year of 1986.

Figure 1.

Changes over time in the incidence rates of acute stroke in patients with acute myocardial infarction (Worcester Heart Attack Study)

After controlling for demographic factors, comorbid conditions, AMI associated characteristics and hospital complications, the odds of experiencing a stroke during hospitalization for AMI were significantly higher in 1997 and 1999 compared to the index year of 1986 (Table 3). In the other study years, the odds of stroke were not significantly different from that observed in our initial two study years of 1986 and 1988.

Table 3.

Changing trends in the occurrence of stroke after acute myocardial infarction (Worcester Heart Attack Study).

| Model 1† | Model 2‡ | |

|---|---|---|

| Study years | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

| 1986 / 1988* | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 1990 / 1991 | 0.76 (0.30, 1.95) | 0.83 (0.38, 1.81) |

| 1993 / 1995 | 1.36 (0.62, 3.40) | 1.48 (0.74, 2.97) |

| 1997 / 1999 | 1.98 (1.02, 3.83) | 2.34 (1.19, 4.59) |

| 2001 / 2003 | 1.53 (0.78, 3.01) | 1.87 (0.93, 3.78) |

| 2005 | 1.01 (0.41, 2.47) | 1.37 (0.54, 3.47) |

Referent years

Adjusted for age, sex, co-morbid conditions (history of angina, diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, atrial fibrillation) and AMI associated characteristics (AMI order and type).

Additional adjustments for development of hospital complications (atrial fibrillation, heart failure, cardiogenic shock), and receipt of in-hospital thrombolytic therapy and cardiac procedures (cardiac catheterization, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass graft surgery).

Among patients who experienced an acute stroke, there were few changes over time in the demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients. Patients with an AMI who experienced a stroke during recent study years were more likely to have a history of hypertension and less likely to have developed a Q-wave or Anterior AMI during their index hospitalization. Greater Worcester residents experiencing a stroke in the 2000’s were less likely than those experiencing a stroke in earlier years to have received thrombolytic therapy during their acute hospitalization (all p-values < .05).

Hospital case-fatality rates of acute stroke and factors associated with a poor hospital prognosis

Patients who experienced an acute stroke during hospital admission for AMI were significantly more likely to die during hospitalization compared to those who did not experience a stroke (34.1% vs. 11.6%; p< 0.001). In our fully adjusted regression model, patients with AMI who experienced a stroke were nearly four times as likely to die during their acute hospitalization compared to those who did not experience a stroke (OR = 3.76; 95% CI = 2.51, 5.65). In addition to stroke, increasing age, a prior medical history of hypertension, development of an anterior AMI, and receipt of a DNR order were associated with a higher risk of dying, while undergoing a PCI was associated with a lower risk of dying during hospitalization. (results not shown). When patients with a DNR order were excluded from the analysis, the results did not materially change and patients who experienced an acute stroke were significantly more likely to die compared to those who did not experience a stroke (OR=2.3, 95% CI =1.2, 4.4).

Among patients who developed a stroke since 1991 (n=114), patients who experienced a hemorrhagic stroke were significantly more likely to die during hospitalization compared to those who experienced an ischemic stroke (OR = 4.14; 95% CI = 1.47, 11.71). There were no differences in hospital death rates in patients who developed an acute stroke according to selected demographic characteristics, clinical factors or prior co-morbidities.

In examining potentially changing trends in the odds of dying after stroke, in the 1980’s patients who experienced a stroke were five times as likely to die during hospitalization (adjusted OR = 4.91; 95% CI = 1.21, 19.84); in the 1990’s patients who experienced a stroke were nearly three times as likely to die (adjusted OR=2.91; 95% CI = 1.72, 5.19); and in the 2000’s patients with a stroke were more than five times as likely to die (adjusted OR = 5.36; 95% CI = 2.71, 10.64) in comparison to those who did not experience a stroke. Expressed in another manner, compared to patients who experienced a stroke in the 1980s, those who developed a stroke in the 1990’s were less likely to die during hospitalization for AMI (adjusted OR = 0.65; 95% CI = 0.22, 1.96). The risk of dying during hospitalization was similar for patients experiencing a stroke in the 2000’s compared to those who developed a stroke in the 1980’s (adjusted OR = 1.04; 95% CI = 0.32, 3.32).

Since the length of hospital stay has declined over time, we also examined 30-day death rates in patients who did and did not develop a stroke according to time. The 30-day death rate after hospital admission was significantly higher in patients who experienced a stroke than in those who did not (37.9% vs. 14.2%; p<.0001). The 30-day death rate increased slightly over the period of study in patients who experienced an acute stroke (Table 4).

Table 4.

Thirty-day case-fatality rates (CFR) after hospital admission according to stroke status and time period. (Worcester Heart Attack Study)

| Stroke | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Years | Present | Absent | p-value | ||

| N | CFR% | N | CFR% | ||

| 1986 / 1988 | 5 | 38.5 | 234 | 18.2 | 0.06 |

| 1990 / 1991 | 6 | 46.2 | 218 | 15.0 | 0.001 |

| 1993 / 1995 | 6 | 25.0 | 236 | 14.0 | 0.12 |

| 1997 / 1999 | 14 | 36.8 | 242 | 13.4 | <0.001 |

| 2001 / 2003 | 7 | 46.7 | 155 | 14.5 | <0.001 |

| 2005 | 5 | 55.6 | 97 | 12.3 | <0.001 |

Discussion

The results of this community-wide study of greater Worcester residents hospitalized with AMI between 1986 and 2005 suggest that the incidence rates of initial stroke events increased from the mid-1980’s through the late 1990’s but has declined somewhat thereafter. Our results also suggest that while the occurrence of stroke complicating AMI appears to be decreasing during recent study years, there is not a corresponding decline in the hospital death rates of those developing an acute stroke. We identified several demographic and clinical factors associated with a greater risk of developing, as well as dying after, a stroke in residents of the Worcester metropolitan area hospitalized with AMI at all area medical centers.

Incidence of stroke complicating AMI

Published studies have shown the hospital incidence rates of stroke complicating AMI to range from 1–2%.2 Despite the morbidity and mortality associated with this devastating condition, little published information is available that has examined changing trends in the magnitude of stroke complicating AMI. Data from the population-based Rochester (MN) Epidemiology Project showed increased rates of stroke following AMI from the late 1970’s through the 1980’s with a leveling off in the 1990’s.5 Findings from the multinational Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events project suggest that the occurrence of stroke in patients hospitalized with acute coronary disease at approximately 100 medical centers throughout the U.S, Europe, and South America between 1999 and 2005 remained relatively stable.4 Previous findings from the Worcester Heart Attack Study suggested declines in the frequency of stroke complicating AMI from the mid through the late 1980’s followed by an increase through the late 1990’s.6 The present study extends our earlier findings and suggests slightly declining rates of acute stroke in the setting of AMI during recent years.

Although we do not have data in the current study to support our speculated hypothesis, our recently observed declines in the incidence rates of acute stroke suggest that contemporary management strategies for patients hospitalized with AMI may be favorably lowering the risk for cerebrovascular complications. The decreased rate of stroke we observed in our study population during the past 5 years is coincident with marked declines in the use of thrombolytic therapy in this patient population, and increased use of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), which may reduce the risk of hemorrhagic stroke in patients with AMI.5 It remains important to continue to monitor changing trends in the magnitude and outcomes of stroke in patients hospitalized with AMI as the therapeutic management of these patients continues to evolve.

Risk factors for stroke complicating AMI

We identified several patient characteristics independently associated with a greater risk for stroke. These included advanced age (≥75 years), female gender, development of atrial fibrillation during hospitalization, and history of a previous MI. These findings are consistent with the results of previously published studies.2, 5, 6, 15–17 In particular, advanced age and occurrence of atrial fibrillation have been consistently identified as risk factors for hospital stroke in the setting of AMI. On the other hand, there is conflicting published evidence with respect to therapeutic regimens possibly associated with the development of stroke complicating AMI; much of this prior work has focused on the potentially adverse effects associated with administration of thrombolytic therapy or has been conducted within the setting of acute clinical trials of prescribed therapies.17, 18 We found that undergoing a PCI was associated with a lower risk for stroke after controlling for a variety of demographic and clinical factors. These results are consistent with findings from the Rochester Epidemiology Project which reported a lower risk of stroke in the setting of AMI in patients who received a PCI.5 A meta-analysis of more than 20 published studies, however, did not identify any therapies associated with a reduced risk for stroke in patients hospitalized with AMI.2 Our findings suggest that patients at increased risk for developing a stroke can be identified in advance. Increased surveillance, and use of targeted therapies, where indicated, is warranted in these high risk patient groups.

Hospital case-fatality rates

The death rates associated with acute stroke in patients with AMI are high, with patients who experience a stroke being 2 to 4 times more likely to die during hospitalization compared to those who do not experience a stroke.2, 5, 6, 16, 19 In our review of the literature, we were unable to find other studies that have examined changing trends in the hospital death rates of patients with AMI who developed a stroke. In the present study, we found that the odds of dying during hospitalization for MI in patients with an acute stroke were higher in more recent years compared to the late 1990’s. While hospital case-fatality rates in patients with acute coronary disease are declining,20 and the rate of stroke complicating AMI is declining in our hospitalized cohort, the odds of an acute stroke being fatal are not showing similar declines.

It is possible that contemporary therapies for AMI may be reducing the risk of stroke complications. However, the occurrence of stroke may be increasingly important with respect to short-term mortality risk after AMI. The higher odds of dying during hospitalization, as well as at 30 days after hospital admission, in patients experiencing an acute stroke since 2000 compared to the odds in the 1990s is especially important given recent reports of decreasing mortality rates associated with stroke in a number of community-wide studies.21, 22 While the death rates in patients who experienced a stroke did not differ according to various demographic, clinical factors, or comorbidities of AMI, patients who experienced an ischemic stroke were less likely to die than those who developed a hemorrhagic stroke. Since stroke subtype has been shown to affect the risk of dying in patients with AMI,23 changes over time in the relative magnitude of hemorrhagic as compared to ischemic strokes may be playing a role in the changing epidemiology of stroke and associated short-term case-fatality rates. Other contributory factors may include changes in the natural history of stroke or due to the less aggressive treatment of these high risk patients. The latter may be due in part to the increasing prevalence of important co-morbidities or to the increasing use of DNR orders in these high risk patients.

Study Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include the generalizability of our population-based study design that included all patients hospitalized with AMI from a well-characterized urban New England community. All cases of possible AMI were independently validated according to standardized criteria. Moreover, since patients’ medical history and hospital care were well characterized, we were able to control for a number of potentially confounding factors in examining changing trends in the magnitude and impact of stroke in patients hospitalized with AMI. The limitations of our study include that the diagnosis of stroke was not always confirmed by a neurologist or imaging studies and we did not have information available about the severity of the acute stroke, availability of a stroke team, or withdrawal of mechanical support. In addition, since we were unable to determine whether in-hospital treatment approaches were prescribed either prior to or after the acute stroke occurred, we did not adjust for receipt of in-hospital medications in the multivariate adjusted regression models. We were we unable to examine the role of other risk factors for stroke, such as cigarette smoking, and information on cause-specific death rates was not available.

Conclusions

The results of our study in residents of a large New England community suggest that the risk of stroke complicating AMI has declined somewhat since the late 1990’s but the short-term death rates of those experiencing stroke are not showing a corresponding decrease. Understanding factors associated with the risk of stroke after AMI, particularly those associated with fatal stroke, remains an important issue for the more optimal care of the increasing number of patients at risk for serious complications of AMI.

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible by the cooperation of the medical records, administration, and cardiology departments of participating hospitals in the Worcester metropolitan area and through funding support provided by the National Institutes of Health (RO1 HL35434).

References

- 1.Goldberg RJ, Spencer FA, Yarzebski J, et al. A 25-year perspective into the changing landscape of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction (the Worcester Heart Attack Study) The American Journal of Cardiology. 2004;94:1373–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witt BJ, Ballman KV, Brown JRD, Meverden RA, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL. The Incidence of Stroke after Myocardial Infarction: A Meta-Analysis. The American Journal of Medicine. 2006;119:354.e1–354.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanne D, Gottlieb S, Hod H, Reicher-Reiss H, Boyko V, Behar S. Incidence and Mortality From Early Stroke Associated With Acute Myocardial Infarction in the Prethrombolytic and Thrombolytic Eras. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1997;30:1484–1490. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budaj A, Flasinska K, Gore JM, et al. Magnitude of and Risk Factors for In-Hospital and Postdischarge Stroke in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: Findings From a Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Circulation. 2005;111:3242–3247. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.512806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witt BJ, Brown RD, Jr, Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, Yawn BP, Roger VL. A Community-Based Study of Stroke Incidence after Myocardial Infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:785–792. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-11-200512060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spencer FA, Gore JM, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Jackson EA, Goldberg RJ. Trends (1986 to 1999) in the incidence and outcomes of in-hospital stroke complicating acute myocardial infarction (The Worcester Heart Attack Study) The American Journal of Cardiology. 2003;92:383–388. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00654-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Recent changes in attack and survival rates of acute myocardial infarction (1975 through 1981). The Worcester Heart Attack Study. Jama. 1986;255:2774–2779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Incidence and case fatality rates of acute myocardial infarction (1975–1984): The Worcester Heart Attack Study. American Heart Journal. 1988;115:761–767. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90876-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Gore JM. A two-decades (1975 to 1995) long experience in the incidence, in-hospital and long-term case-fatality rates of acute myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1999;33:1533–1539. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg RJ, Gorak EJ, Yarzebski J, et al. A communitywide perspective of sex differences and temporal trends in the incidence and survival rates after acute myocardial infarction and out-of-hospital deaths caused by coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1993;87:1947–1953. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.6.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Wu J, Gore JM. Recent trends in the incidence rates of and death rates from atrial fibrillation complicating initial acute myocardial infarction: A community-wide perspective. American Heart Journal. 2002;143:519–527. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.120410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spencer FA, Meyer TE, Goldberg RJ, et al. Twenty year trends (1975–1995) in the incidence, in-hospital and long-term death rates associated with heart failure complicating acute myocardial infarction : A community-wide perspective. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1999;34:1378–1387. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00390-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg RJ, Samad NA, Yarzebski J, Gurwitz J, Bigelow C, Gore JM. Temporal Trends in Cardiogenic Shock Complicating Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1162–1168. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sampson UK, Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJV, et al. Predictors of stroke in high-risk patients after acute myocardial infarction: insights from the VALIANT trial. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:685–691. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mooe T, Eriksson P, Stegmayr B. Ischemic Stroke After Acute Myocardial Infarction : A Population-Based Study. Stroke. 1997;28:762–767. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.4.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wienbergen H, Schiele R, Gitt AK, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcome of stroke after acute myocardial infarction in clinical practice. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2001;87:782–785. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01505-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahaffey KW, Granger CB, Sloan MA, et al. Risk Factors for In-hospital Nonhemorrhagic Stroke in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction Treated With Thrombolysis : Results From GUSTO-I. Circulation. 1998;97:757–764. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.8.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurwitz JH, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ, et al. Risk for Intracranial Hemorrhage after Tissue Plasminogen Activator Treatment for Acute Myocardial Infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:597–604. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-8-199810150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng P, Chan W, Kwan P. Risk of stroke after myocardial infarction among Chinese. Chinese Medical Journal. 2001;114:210–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox KAA, Steg PG, Eagle KA, et al. Decline in Rates of Death and Heart Failure in Acute Coronary Syndromes, 1999–2006. JAMA. 2007;297:1892–1900. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.17.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Giles MF, et al. Change in stroke incidence, mortality, case-fatality, severity, and risk factors in Oxfordshire, UK from 1981 to 2004 (Oxford Vascular Study) The Lancet. 2004;363:1925–1933. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sturgeon JD, Folsom AR. Trends in hospitalization rate, hospital case fatality, and mortality rate of stroke by subtype in Minneapolis-St. Paul, 1980–2002. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;28:39–45. doi: 10.1159/000097855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gore JM, Granger CB, Simoons ML, et al. Stroke After Thrombolysis : Mortality and Functional Outcomes in the GUSTO-I Trial. Circulation. 1995;92:2811–2818. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.10.2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]