Abstract

Exposure to stressors during particular stages of development leads to acute and long-term physiological and behavioral changes. We have reported that shipping mice during the peripubertal/adolescent period results in decreased induction of feminine sexual behavior by estradiol and progesterone in adult female mice. To study further the factors involved in this decreased behavioral response, female mice were exposed to a variety of experimental stressors when 6 wk old. Effects of peripubertal/adolescent exposure to these stressors on acute plasma corticosterone levels and changes in body weight and adult behavioral response to estradiol and progesterone were assessed. Although restraint for three daily 3-h periods, 36-h food deprivation, or a multiple stressor regimen acutely increased plasma corticosterone levels and reduced body weight, only exposure to particular doses of the bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 1–1.5 mg/kg body weight, doses that induced moderate levels of sickness behavior in these studies) resulted in reduced behavioral response to estradiol and progesterone in adulthood. Like the effects of shipping, the effects of LPS on adult feminine sexual behavior appear most robust when injected at 6 wk old and are limited to exposure during a vulnerable period at approximately 4–6 wk of age. Therefore, an immune stressor during the peripubertal/adolescent period, but not restraint, food restriction, or a combined stressor, has an enduring influence on behavioral response to estradiol and progesterone. This demonstrates that the decreased response to estradiol and progesterone is not a general response to all stressors during this developmental stage.

Treatment of female mice with the bacterial endotoxin, lipopolysaccharide, during the peripubertal/adolescent period decreases behavioral response to estradiol and progesterone in adulthood, suggesting that particular stressors during this period have enduring influences on behavioral response to sex steroid hormones.

Puberty is a critical period in the establishment of some reproductive behaviors (1,2,3) as well as regulation of the hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal (4) and hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axes (5,6). Likewise, exposure to a variety of perinatal stressors can have permanent behavioral, morphological, and neuroendocrine effects (7,8,9,10). Female mice are also vulnerable to stress-induced disruption of the HPA axis around the time of puberty; exposing peripubertal female mice to immobilization stress causes a persistent shift in the peak of the daily corticosterone secretion rhythm and a loss of daily rhythmic variations (11). Exposure to stressors also has long-term effects on the reproductive capacity of female mice. Exposure to heat stress, immobilization stress, or ether stress starting at 40 d of age leads to reduced fertility, possibly secondary to a deficit in reproductive behavior (12).

A variety of stressors, each of which activates the HPA axis, has been used routinely in rodents. Restraint stress (13,14) suppresses LH release in female rats (15) and has other inhibitory effects on reproduction. Food deprivation and restriction are also potent stressors. In female mice, food restriction delays ovulation (16) and decreases LH levels (17). Chronic food restriction during development in mice may decrease uterine and ovarian weights, number of females ovulating, and ovulatory responses to gonadotropin treatment (18,19). In young female rats, food restriction delays the onset of puberty by inhibiting GnRH secretion, and it is believed that the inhibition of GnRH secretion by food deprivation in turn inhibits the LH surge (20). Although food deprivation delays the onset of puberty in female mice (21), the long-term effects of this stressor on reproductive behaviors are unknown.

Another class of stressors that has been used is immune stressor. These induce a robust immune and stress response and temporarily induce sickness behavior (22) The bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS), isolated from the bacterial cell wall of Gram negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, induces an increase in plasma corticosterone (23) and is believed to activate the HPA axis by inducing the release of cytokines (24,25).

Exposing female mice to the stress of shipping from suppliers during the peripubertal/adolescent period reduces the expression of feminine sexual behavior in response to estradiol and progesterone during adulthood (26). Because of these robust effects, we examined the effects of exposure to typical well-controlled, experimental stressors during this period on adult feminine sexual behavior. In addition to assessing the effects of single stressors, we used a modified version of an established multiple stressor paradigm, which included heat, bright light, and restraint (27). During shipping, mice are potentially exposed to a wide variety of stressors, including noise, vibrations, changes in temperature, disruption of circadian rhythms, noxious and predator odors, social instability, decreases in food or water consumption, and others. In this series of experiments, no attempt was made to duplicate these particular stressors, because they are likely to be quite variable from shipment to shipment, and even the duration of shipping can vary from 1–2 d. Rather, the goal was to determine whether some of the typical stressors that are routinely applied in a laboratory setting and that induce increases in corticosterone secretion are capable of duplicating the effects of shipping.

To determine whether the long-term effects of exposure to the stressors are due to the release of adrenal corticosteroids, plasma corticosterone was assayed shortly after stressor exposure. Decreases in body weight were examined as one index of stress and because food restriction is itself a robust stressor. Finally, we assessed the effects of an immune stressor, LPS administration. It is not known whether mice are exposed to pathogens during shipping from suppliers, because they are shipped in filtered crates. LPS was used because its overall duration of action approximates that of shipping.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. All female C57BL/6 mice used in these studies were bred at the University of Massachusetts from breeders obtained from Taconic Farms (Hudson, NY) or Charles River Laboratories (Kingston, NY). Mice were housed with free access to food (Teklad 2014, phytoestrogen-reduced diet) and water. Animals were housed in a colony room under a controlled environment, with a consistent temperature (∼24 ± 2 C) and reversed 14-h light, 10-h dark cycle (lights off at 1000 h). A combination of wood shavings and CareFRESH (International Absorbents, Inc., Ferndale, WA) bedding was used, and a fresh Nestlet (Ancare Corp., Baltimore, NY) was placed in the cage when bedding was changed. When handling occurred during the dark phase of the cycle, dim red illumination was used.

For breeding, four experienced C57BL/6 breeder female mice were placed in each cage (30.5-cm × 19.5-cm × 12.0-cm shoebox polycarbonate with wire lid) with an experienced male of the same strain. The females were left with the male and removed to its own cage when visibly pregnant (before the third trimester). Pups were weaned and separated from their mothers 21 d after birth. At weaning, mice were group-housed by sex, three per cage, until they were assigned to an experiment. The procedure for ovariectomy was identical to that previously described (26).

Removing the mice from their cages, exposing them to a novel environment, drawing a blood sample, and returning them to their cages would constitute an additional stressor and therefore a potential confound to the behavioral experiment. In addition, we could not predict the potential confounding influences of daily handling on subsequent behavioral response. Therefore, it was deemed prudent to use independent groups of mice for assessment of female sexual behavior, corticosterone levels, and changes in body weight.

Female sexual behavior testing

Seven to 10 d after ovariectomy, mice were tested for the expression of sexual receptivity in response to a sc injection of 2 μg estradiol benzoate (dissolved in 0.1 ml sesame oil), followed 44 h later by 100 μg progesterone (dissolved in 0.1 ml sesame oil containing 5% benzyl alcohol and 15% benzyl alcohol). Approximately 6 h later, mice were tested for female sexual behavior in response to a sexually vigorous male mouse. A sexually experienced stimulus male was placed in a Plexiglas arena (18 × 38 cm) (28) on a mirror stand, which allowed a ventral view of the behavioral interactions with one female until 20 mounts had occurred. Mounts, defined as both of the male’s forepaws on the female’s hind region, as well as intromissions, were scored. Scoring a lordosis response required that the female hold a rigid posture with slight arching of the back, and elevation of the hindquarters to facilitate mount and intromission by the male (29). The lordosis quotient (LQ) was calculated as the number of lordosis responses/number of mounts × 100 as an index of sexual receptivity. Because female mice often become nonreceptive after receiving an ejaculation from a male, testing was terminated if the female received an ejaculation. Testing was carried out with scorers blind to the treatment groups. All testing was done under dim red illumination. Weekly tests continued for 5 wk.

Results were contrasted using a repeated-measures two-way ANOVA (treatment × time). Bonferroni post tests were conducted to determine specific pairwise differences at specific time points.

Corticosterone RIA

At specific time points relative to stressors, the mice were euthanized with a lethal dose of chloropent anesthetic, and rapidly decapitated in a separate room from that containing the experimental animals. Trunk blood was collected immediately into EDTA-coated blood collection tubes (Microvette CB 300; Sarstedt, Newton, NC), and placed on ice until sample collection was complete. Blood was centrifuged for 15 min at 3000 rpm at 4 C, and plasma was collected and stored at −20 C until corticosterone levels were assessed by RIA. Plasma corticosterone levels were determined using a corticosterone RIA kit (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) with an intraassay coefficient of variability of 7.1% and an interassay coefficient of variability of 6.5%.

Body weights

Animals were weighed at specific time points as described below.

Restraint stress

Twenty-one female mice (6 wk old) were assigned to one of two groups: control (n = 10) or restraint stress (n = 11). Mice at 6 wk of age were used, because this was the optimal time at which shipping resulted in decreased response to estradiol and progesterone in adulthood (26). Six-week-old female mice are considered peripubertal, because previous research in C57BL/6 mice found onset of vaginal opening at 30 d and onset of estrous cyclicity at approximately 60 d (30). It should be noted that this would be expected to be variable depending upon housing conditions. Although we have not determined onset of estrous cycles in mice in our laboratory, we have determined in a separate study that the vaginas of all animals are open by 6 wk old (Ismail, N., K. M. Olesen, and J. D. Blaustein, unpublished observations). Beginning on postnatal d 42, experimental animals were placed in restraint tubes in their home cages for 3 h/d for 3 d (31), and control mice were left undisturbed in their home cages. Restraint tubes consisted of 50 ml conical centrifuge tubes measuring 9.7 cm in length with an internal diameter of 2.8 cm (Fisher Brand Easy Reader Tubes, Agawam, MA) into which six 0.5-cm holes were drilled. The mice were restrained around the transition from light to dark: (d 1, 0930 h; d 2, 1015 h; d 3, 1045 h), because the response to restraint stress is maximal around this time of day in mice (32). One week later, mice were ovariectomized, and tests for female sexual receptivity began 1 wk later.

In a parallel experiment, 22 female mice (6 wk old) were randomly assigned to one of four groups: d 1 control (n = 6), d 3 control (n = 4), d 1 restraint stress (n = 6), or d 3 restraint stress (n = 5). Trunk blood was collected immediately after exposure to restraint stress on either d 1 or 3 and at similar time points from control animals.

Additional female mice were randomly assigned to either control (n = 5) or restraint stress (n = 6) groups. All animals were weighed at the onset of treatment on d 1, after the first restraint exposure d 1 (d 1, 3 h) and again before and after treatment on d 3 (d 3 at 0 and 3 h).

Food deprivation

Eighteen female mice (6 wk old) were randomly assigned to control (n = 9) or food-deprived (n = 9) groups. Animals were either food deprived for 36 h (17) or left in their home cage with ad libitum access to food and water. Mice were ovariectomized 1 wk later, and testing for female sexual receptivity began 1 wk later.

Thirty-two female mice (6 wk old) were randomly assigned to one of six groups: control 12 h (n = 4), control 24 h (n = 3), control 36 h (n = 4), food-deprived 12 h (n = 7), food-deprived 24 h (n = 6), and food-deprived 36 h (n = 8). Trunk blood was collected from groups of food-deprived and groups of control animals every 12 h, and plasma corticosterone levels were assayed. Other mice were either food deprived (n = 6) or given ad libitum access to food (control; n = 6) and weighed at the onset and then at 12, 24, and 36 h of food deprivation.

Multiple stressors

Six-week-old female mice were either exposed to a multiple stressor (n = 9) or left undisturbed (controls; n = 11). Experimental mice were placed in the restrainers in their home cages for three 45-min sessions per day (each separated by a 1-h, no-stress period) for 3 d while being exposed to light from two 150-W floodlight lamps as previously described (27). Cage temperature was monitored to ensure that the animals were not exposed to temperatures higher than 32 C. The mice were exposed to this multiple stressor regimen near the beginning of the dark phase of the light-dark cycle (d 1, 1030 h; d 2, 1115 h; and d 3, 1145 h). Each group was then subdivided into the following subgroups (where t refers to which multiple stressor exposure session the blood sampling followed): d 1 t = 0 (control n = 7 and multiple stressor n = 8), d 1 t = 1 (control n = 6 and multiple stressor n = 7), d 1 t = 3 (control n = 7 and multiple stressor n = 6), d 3 t = 0 (control n = 6 and multiple stressor n = 7), d 3 t = 1 (control n = 8 and multiple stressor n = 7), or d 3 t = 3 (control n = 8 and multiple stressor n = 8). One week after the end of treatment, mice were ovariectomized, and hormone injections and testing began 1 wk later.

Eighty-five female mice (6 wk old) were randomly assigned to the multiple stressor or control condition. At the specified time point (t = 0, 1, or 3) on d 1 or 3, trunk blood was collected and plasma corticosterone levels were assayed. Additional female mice were randomly assigned to one of two groups: control (n = 6) or multiple stressor (n = 6). They were weighed immediately before the onset of stressor exposure on d 1, after the last exposure on d 1, and at the start and end of d 2 and 3.

Bacterial endotoxin, LPS

Fifty-eight female mice (6 wk old) were injected with LPS (obtained from Escherichia coli serotype O26:B6; no. L3755; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) dissolved in sterile saline at 0930 h and returned to their home cage immediately after injection. Doses of LPS were chosen from previous work of others and ranged from the minimum reported dose that causes a physiological effect in peripubertal female mice to a dose that induces sickness behavior: control (n = 10), 0.1 mg/kg (n = 10), 0.2 mg/kg (n = 7), 0.5 mg/kg (n = 8), 1.0 mg/kg (n = 9), or 1.5 mg/kg (n = 14). Although not quantified in this study, even 1.5 mg/kg causes only mild sickness behavior in mice in this laboratory. In a follow-up study (Olesen, K. M., N. Ismail, and J. D. Blaustein, unpublished observations), 90–100% displayed lethargy and huddling. Fewer than 50% displayed ptosis 4 h after injection, and it was not seen in any animals at 24 h after injection. Only about 45% of the mice continued to display lethargy or huddling at this time point. Animals were fully recovered by 48 h after injection. In the present experiment, no animals died as a consequence of any dose of LPS.

Approximately 1 wk after the LPS injections, the animals were bilaterally ovariectomized, followed by testing for female sexual receptivity 1 wk later.

Forty female mice (6 wk old) were randomly assigned to one of the following groups and injected with LPS as described above: control (n = 6), 0.1 mg/kg (n = 6), 0.2 mg/kg (n = 6), 0.5 mg/kg (n = 6), 1.0 mg/kg (n = 7), and 1.5 mg/kg (n = 7). Two hours after LPS injections, trunk blood was collected and plasma samples assayed for corticosterone levels. Additional female mice were randomly assigned to one of six groups: control (n = 7), 0.1 mg/kg (n = 7), 0.2 mg/kg (n = 7), 0.5 mg/kg (n = 8), 1.0 mg/kg (n = 9), or 1.5 mg/kg (n = 10). Animals were weighed immediately before receiving injections of either sterile saline or LPS 24 and 48 h later.

High dose of LPS

Because the results revealed that only the high dose of LPS significantly affected adult feminine sexual behavior, we repeated the above experiment using only the highest dose of LPS (1.5 mg/kg). LPS or saline was administered to 6-wk-old female mice (n = 11 per group), after which they were ovariectomized and tested for feminine sexual behavior.

Age at LPS injection

One hundred eighteen female mice received either LPS (1.5 mg/kg) or saline injection at the following ages: 3 wk old (LPS, n = 8; control, n = 7), 4 wk (LPS, n = 12, control, n = 7), 5 wk (LPS, n = 10; control, n = 6), 6 wk (LPS, n = 5; control, n = 7), 7 wk (LPS, n = 9, control, n = 7), 8 wk (LPS, n = 10; control, n = 9), or 10 wk (LPS, n = 10; control, n = 5). At 12 wk of age, all animals were ovariectomized and subsequently tested for feminine sexual behavior.

Results

Restraint stress

Exposure to the restraint procedure did not affect LQ (Fig. 1A). A two-way, repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for test session [F(4,76) = 19.42; P < 0.0001], no effect for treatment group [F(1,76) = 0.300; P > 0.05], and no interaction.

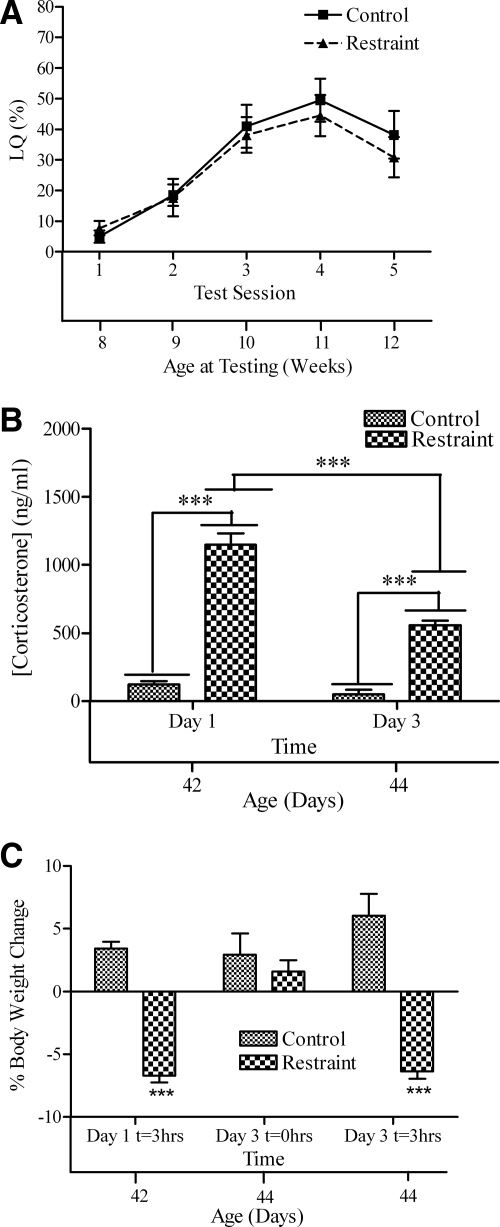

Figure 1.

A, LQ (mean ± sem); B, plasma corticosterone levels; C, percent body weight change of female mice exposed to 3 h restraint at 6 wk old. As a point of reference, the body weight loss at d 3, t = 3 h, corresponds to a 0.87-g loss in body weight contrasted with d 3, t = 0 h. The lower x-axis refers to the animal’s age at time of testing, blood sample, or body weight. Significant differences between restraint and control groups at specific time points are indicated: ***, P < 0.001.

Restraint increased plasma corticosterone levels (Fig. 1B), and this response was attenuated by the third day of treatment. Two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of treatment [F(1,17) = 191.8; P < 0.0001], a main effect of time [F(1,17) = 35.90; P < 0.0001], and a significant interaction between treatment and time [F(1,17) = 22.15, P < 0.0005]. Restraint increased corticosterone levels on both the first day of exposure (d 1; t10 = 14.22; P < 0.001) and the third day of exposure (d 3; t7 = 6.03; P < 0.001), although the corticosterone level in the stressed animals was lower on d 3 than on d 1 (t8 = 7.818; P < 0.001).

Restraint significantly decreased body weight (Fig. 1C). Body weights of the two groups were not significantly different at the onset of the third day of restraint, suggesting that the mice recovered the weight lost during the stress exposure once the stressor was terminated. A two-way, repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time [F(2,18) = 15.56; P = 0.0001] and treatment [F(1,19) = 39.16; P = 0.0001] and a significant interaction [F(2,18) = 34.24; P < 0.0001]. Body weight was suppressed by the stressor after 3 h of restraint on d 1 (t9 = 6.72; P < 0.001) and on d 3 (t9 = 8.20; P < 0.001).

Food deprivation

Food deprivation was without effect on sexual receptivity during adulthood (Fig. 2A). Two-way, repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for test session [F(4,60) = 30.66; P < 0.0001] but no treatment effect [F(1,60) = 0.40; P > 0.05] or interaction [F(4,60) = 0.493; P > 0.05].

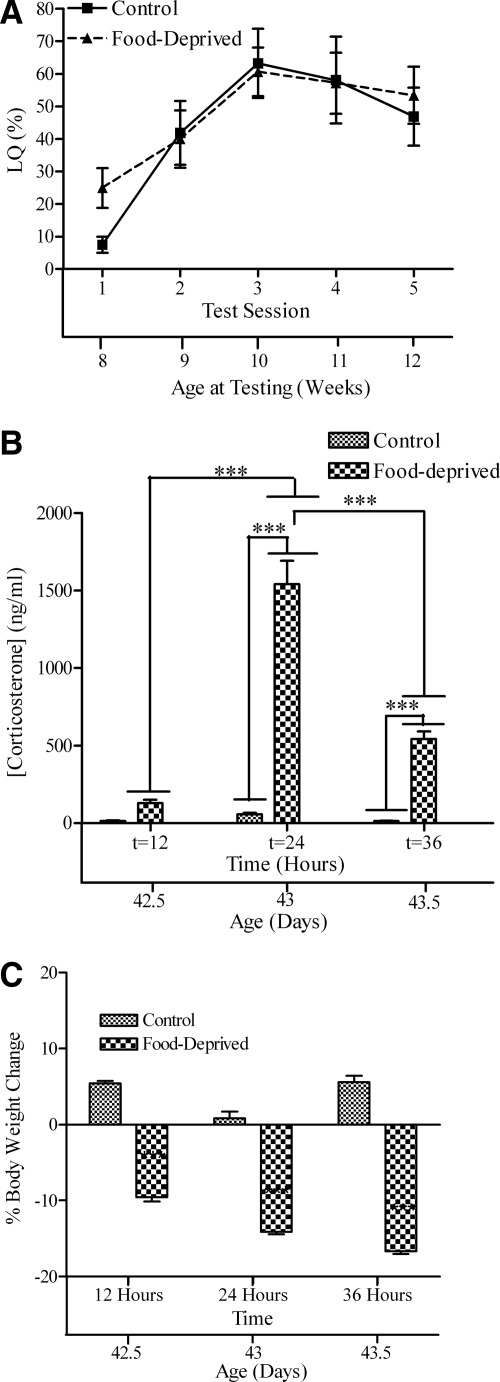

Figure 2.

A, LQ (mean ± sem); B, plasma corticosterone levels; C, percent body weight change of female mice exposed to food deprivation at 6 wk old. The lower x-axis refers to the animal’s age at time of testing, blood sample, or body weight. Significant differences between restraint and control groups at specific time points are indicated: ***, P < 0.001.

Two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of food deprivation on corticosterone levels (Fig. 2A) [F(2,26) = 110.1; P < 0.0001], a main effect of time [F(2,26) = 38.07; P < 0.0001], and a significant interaction [F(2,26) = 33.25; P < 0.0001]. Plasma corticosterone levels were elevated at both 24 h (t7 = 11.65; P < 0.001) and 36 h (t10 = 4.80; P < 0.001) but not at 12 h (t9 = 1.02; P > 0.05). Plasma corticosterone levels decreased between 24 and 36 h (t12 = 10.28; P < 0.001), suggesting that habituation to food deprivation occurred between these two time points.

Food deprivation reduced body weight (Fig. 2C). A two-way, repeated-measures ANOVA revealed main effects for time [F(2,22) = 55.19; P < 0.0001] and treatment [F(1,22) = 827.90; P < 0.0001] and a significant time × treatment interaction [F(2,22) = 43.03; P < 0.0001], reflecting the loss in weight of the food-deprived mice over time. Food deprivation decreased body weight at all three times at which the animals were weighed: after 12 h (t11 = 18.67; P < 0.001), after 24 h (t11 = 18.65; P < 0.001), and after 36 h (t11 = 27.80; P < 0.001) food deprivation.

Multiple stressor

The multiple-stressor procedure did not influence sexual receptivity during adulthood (Fig. 3A). A two-way, repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a main effect for test session [F(4,72) = 30.57; P < 0.0001]. However, exposing female mice to this stressor had no effect on LQ [F(1,72) = 0.86; P > 0.05], and there was no interaction [F(4,72) = 0.81, P > 0.05].

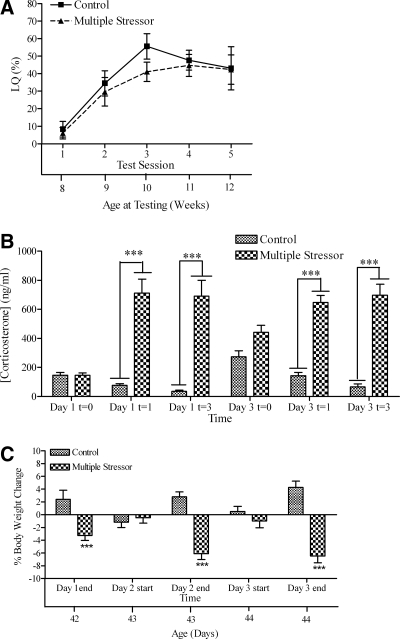

Figure 3.

A, LQ (mean ± sem); B, plasma corticosterone levels [t = 0 (pretreatment on particular day), t = 1 (after first stressor exposure on particular day), t = 3 (after third stressor exposure on particular day)]; C, percent body weight change of female mice exposed to multiple stressor conditions at 6 wk old. The lower x-axis refers to the animal’s age at time of testing (A) or body weight (C). Significant differences between restraint and control groups at specific time points are indicated: ***, P < 0.001.

The multiple stressors increased plasma corticosterone levels (Fig. 3C) [F(1,75) = 52.47; P < 0.0001]. There was also a significant effect of time [F(5,75) = 9.42; P < 0.0001] and a significant interaction [F(5,75) = 20.36; P < 0.0001]. Post hoc analyses revealed that exposure to a multiple stressor increased plasma corticosterone levels at both time points on both days.

In addition to acutely increasing plasma corticosterone levels, daily exposure to the multiple stressor caused the basal plasma corticosterone levels (at t = 0, before multiple stressor exposure on that day) to be higher on d 3 than on d 1 (t13 = 4.15; P < 0.001). Moreover, we observed a time-of-day effect on plasma corticosterone levels in the control group, such that on both d 1 and 3, significantly lower serum corticosterone levels were observed at the time corresponding to the end of the third exposure (t = 3) than the levels observed at t = 0 (t12 = 2.51; P < 0.05 on d 1 and t13 = 3.56; P < 0.01 on d 3). This time-of-day effect is consistent with circadian variations in corticosterone secretion in mice in which basal blood corticosterone levels vary throughout the light-dark cycle and are higher at the beginning of the dark phase.

Exposure to the multiple stressors significantly reduced body weight (Fig. 3C). A repeated-measures two-way ANOVA revealed a main group effect [F(1,40) = 22.50; P < 0.0001] but no effect of time [F(4,40) = 1.58; P > 0.05]. There was a significant interaction effect between time and treatment [F(4,40) = 29.93; P < 0.0001]. Body weights of treated mice were lower than the controls after each daily exposure to the multiple stressor (d 1: t10 = 4.19, P < 0.001; d 2: t10 = 6.58, P < 0.001; d 3: t10 = 7.92, P < 0.001).

Bacterial endotoxin, LPS

The highest LPS dose was the most effective at decreasing the sexual behavior response of adult female mice, and it was the only dose that decreased the level of sexual receptivity at more than one session (Fig. 4A). Repeated-measures two-way ANOVA revealed main effects for test session [F(4,208) = 40.41; P < 0.0001] and treatment group [F(5,208) = 7.12; P < 0.005] and a significant interaction [F(20, 208) = 7.97; P < 0.0001].

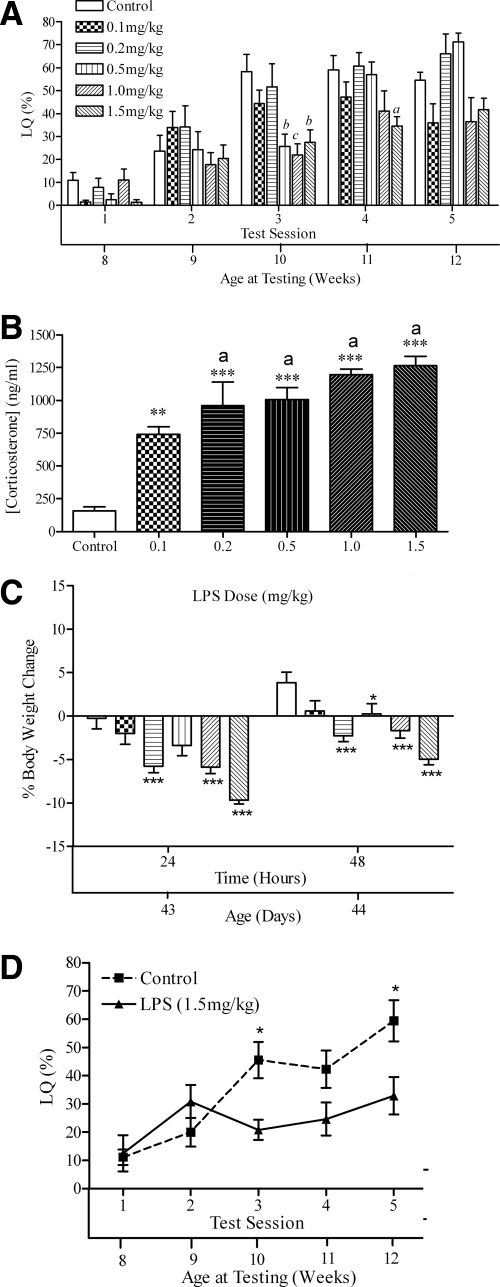

Figure 4.

A, LQ (mean ± sem); B, plasma corticosterone levels; C, percent body weight change of female mice injected with various doses of LPS at 6 wk old; D, LQ (mean ± sem) of female mice exposed to one 1.5 mg/kg dose of LPS at 6 wk old. The lower x-axis refers to the animal’s age at time of testing, blood sample, or body weight. In A, significant differences between restraint and control groups at specific time points are indicated: a, P < 0.05; b, P < 0.01; c, P < 0.001. In B–D: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; and a, no significant difference among these groups (B).

Statistically significant differences in LQ were observed on test session 3 between control mice and mice receiving 0.2 mg LPS/kg (t16 = 3.64; P < 0.01) or 1.0 mg LPS/kg (t17 = 4.18; P < 001). Statistically significant differences in LQ were observed between mice exposed to 1.5 mg LPS/kg at test session 3 (t22 = 3.93; P < 0.001) and test session 4 (t22 = 3.12; P < 0.05).

Injection of LPS caused a dose-dependent increase in corticosterone secretion (Fig. 4B) [F(5,36) = 20.07; P < 0.005], but the four highest doses did not significantly differ in their effectiveness in increasing corticosterone levels. Treatment with LPS significantly reduced body weight (Fig. 4C). Repeated-measures two-way ANOVA (treatment × time) revealed main effects of time [F(1,42) = 279.8; P < 0.0001] and treatment [F(1,42) = 12.36; P < 0.0001] but no significant interaction. Body weight was reduced in the 0.2 mg/kg group at both 24 h (t12 = 3.83; P < 0.001) and 48 h (t12 = 4.25; P < 0.001), the 0.5 mg/kg group at 48 h (t13 = 2.60; P < 0.05), the 1.0 mg/kg group at 24 h (t14 = 4.12; P < 0.001) and 48 h (t14 = 4.07; P < 0.001), and the 1.5 mg/kg group at 24 h (t15 = 7.08; P < 0.001) and 48 h (t15 = 6.63; P < 0.001).

High dose of LPS

The results confirmed the finding that a single high-dose injection of LPS on d 42 decreased the behavioral response to estradiol and progesterone in adulthood (Fig. 4D). Repeated-measures, two-way ANOVA revealed effects of test session [F(4,76) = 23.61; P < 0.0001] and treatment [F(1,76) = 6.37; P < 0.05] and an interaction between the two factors [F(4,76) = 9.07; P < 0.005]. Posttest analyses confirmed reductions in sexual behavior in the LPS group at test session 3 (t19 = 2.88, P < 0.05) and at test session 5 (t19 = 3.09, P < 0.05).

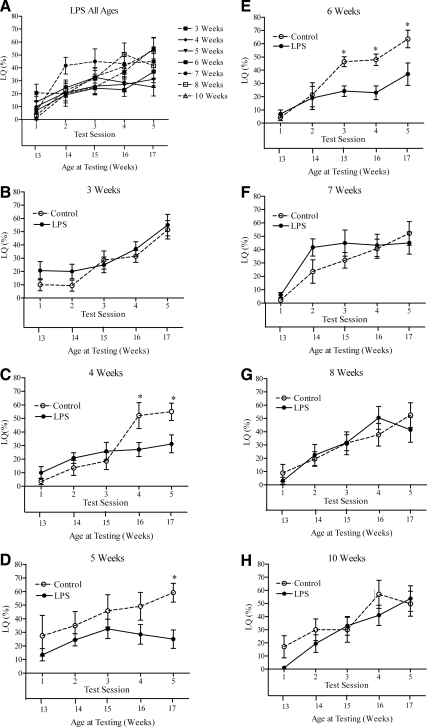

Age at LPS exposure

Age at exposure is a critical factor in the effectiveness of LPS in decreasing behavioral response to estradiol and progesterone. Exposing 4-, 5-, or 6-wk-old mice to LPS significantly reduced the levels of feminine sexual behavior in adulthood, whereas treatment with LPS at either 3 wk old or 7 wk and older did not significantly reduce the levels of feminine sexual behavior in response to estradiol and progesterone in adulthood.

Two-way ANOVAs for each age group revealed that LPS decreased feminine sexual behavior (i.e. either a statistically significant main effect or interaction between test session and LPS) only when administered at 4, 5, or 6 wk of age. Mice injected at 6 wk of age (Fig. 5E) had suppressed levels of sexual behavior [F(1,40) = 12.97; P < 0.005] contrasted with controls on tests 3, 4, and 5. Sexual behavior was suppressed in mice that had been injected with LPS at 5 wk old (Fig. 5D) [F(1,56) = 5.899; P < 0.05] but only at test session 5 (t14 = 2.92; P < 0.05). Although there was no main effect of LPS treatment [F(1,68) = 1.436; P > 0.05] in mice treated at 4 wk old (Fig. 5C), there was a statistically significant interaction between test session and LPS [F(4,68) = 4.459; P < 0.005]. LPS-treated female mice showed lower levels of sexual behavior during test sessions 4 (t17 = 2.899; P < 0.05) and 5 (t17 = 2.748; P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

LQ (mean ± sem) of female mice injected with 1.5 mg/kg LPS at 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, or 10 wk of age. The lower x-axis refers to the animal’s age at time of testing. Significant differences between restraint and control groups at specific time points are indicated: *, P < 0.05.

The LQ of female mice treated with either LPS or vehicle at 3 wk of age increased over test sessions (Fig. 5B) [F(1,52) = 14.14; P < 0.0001]. However, exposure to LPS had no significant main effect on adult feminine sexual behavior [F(1,52) = 1.665; P > 0.05], and the LQ did not differ on any of the test sessions (P > 0.05). Likewise, for mice injected at 7, 8 or 10 wk of age (Fig. 5, F–H), there was an effect of test session [7 wk: F(4,56) = 12.25, P < 0.0001; 8 wk: F(4,68) = 14.05, P < 0.0001; 10 wk: F(4,52) = 12.28, P < 0.0001], but there were no effects of LPS treatment (P > 0.3) in animals injected at these ages [7 wk: F(1,56) = 1.13, P > 0.30; 8 wk: F(1,68) = 0.0003, P > 0.99; 10 wk F(1,52) = 3.07, P > 0.35], and there was no interaction between the two main factors (P > 0.4) in any of these age groups). Pairwise comparisons at each test session did indicate differences in feminine sexual behavior in any of the groups (P > 0.05 in all cases).

Although we did not quantify sickness behavior in this study, no animals died as a result of LPS treatment, and mice at all ages experienced mild sickness behavior. We cannot exclude the possibility that there is a difference in degree of sickness at different ages at injection.

Discussion

Exposure to LPS during the peripubertal/adolescent period resulted in decreased behavioral response to estradiol and progesterone in adulthood, similar to what is seen when mice of the same strain are shipped from suppliers at the same developmental stage (26). Surprisingly, of the four experimental stressors examined, only LPS caused this reduction in feminine sexual behavior induced by estradiol and progesterone, suggesting that the decreased response to sex hormones in adulthood is not a generalized response to all stressors during the peripubertal/adolescent period.

The effects of LPS on estradiol- and progesterone-dependent feminine sexual behavior are limited to the peripubertal/adolescent period and are most robust around 6 wk of age. The disruptive effects of LPS on sexual behavior were less robust when administered before 6 wk of age, although some effects were seen in mice treated at 4 or 5 wk of age. These results are in agreement with those obtained in animals shipped at various ages from weaning to adulthood in our previous report (26). In both cases, female mice exposed to the stressor around the time of weaning (3 wk) or later than 6 wk appeared to be insensitive to the effects of the stressor. Both age and sex affect LPS activation of the HPA axis. In the neonatal and the infantile period (until postnatal d 7), mice are relatively unresponsive to LPS, as inferred from the absence of a corticosterone response. However, female, but not male, mice are responsive to LPS during the juvenile period (until d 15). Finally, the maximal LPS-induced corticosterone response occurs at around 30 d in males and around 45 d in females (33).

In contrast to shipping and the higher doses of LPS, restraint stress, food deprivation, and the multiple stressor procedure are not sufficient to influence the expression of adult sexual behavior. It should be noted that even restraint stress is a form of multiple stressor, because the mice are exposed to food and water restriction and thermoregulatory problems during the 3-h periods. This suggests that the LPS-induced change in response to estradiol and progesterone is unlikely to be caused solely by an acute increase in corticosterone, because all of these stress procedures increased corticosterone levels. In addition, the multiple stressor procedure elevated basal corticosterone levels, indicating that long-term corticosterone hypersecretion is not sufficient to disrupt adult behavioral response. Furthermore, all doses of LPS significantly increased corticosterone level, and the four highest doses did not differ significantly from each other. Likewise, the decreased behavioral response is also unlikely to be due to the stress associated with the acute decrease in body weight, because many of the doses of LPS and the other stressors caused large acute decreases in body weight, but only the highest dose of LPS decreased adult behavioral response to estradiol and progesterone on more than one test. However, the change in body weight was greatest at this dose of LPS, supporting the idea that LPS-induced decrements in sexual behavior may be related to the relative intensity of the stressful experience.

There are a number of caveats related to the present work. The effects of LPS were limited to exposure during the peripubertal/adolescent period, with the most robust effects seen at 6 wk of age, followed by 5 wk and then 4 wk. Although progressively higher LPS doses did not differ noticeably in their ability to induce corticosterone release, only one time point was sampled, so we cannot be certain that the duration of the corticosterone response did not differ among doses of LPS. Furthermore, the results suggest that stress-induced increases in plasma corticosterone levels and decreases in body weight during the peripubertal period are not sufficient to induce long-term effects on feminine sexual behavior. Thus, it is probable that alternative stress-related factors common to shipping and LPS may be responsible for impaired sexual responsiveness.

The results presented here suggest that the reduced behavioral response to estradiol and progesterone after peripubertal/adolescent treatment of mice with LPS are long lasting, as was the case with shipping reductions in female sexual behavior (26). Although we have not determined how long into adulthood this decrease in response to the sex steroid hormones persists, the final test in the last experiment occurred at 17 wk and at 18 wk of age in our previous shipping experiment (26).

The present experiments do not inform us of the mechanism by which behavioral response to estradiol and progesterone in adulthood is suppressed by particular peripubertal stressors. Both stress exposure and LPS can induce the synthesis and release of cytokines (e.g. IL-6) in the brain and periphery (34), which may then have robust effects on the brain and behavior (35,36,37). We cannot exclude the possibility that peripubertal stressors alter secretion of sex steroid hormones, which in turn may influence sexual differentiation of the brain. It is possible that the peripubertal/adolescent stressors induce changes in the neuroendocrine response to these hormones directly by, for example, changes in receptor or coactivator level or function in critical brain areas. Because the sexual behavior of ovariectomized mice increases in weekly tests (29,38,39), and corticosterone release in response to the testing situation has been implicated in this slow response (40), it is also possible that the peripubertal/adolescent treatments cause dysregulation of the corticosterone response to stress in adulthood and that the altered behavioral response is secondary to these changes. Regardless of whether the mechanism by which particular peripubertal/adolescent challenges decrease sex behavioral response is via the HPA axis, hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axis, or both, it is likely that other behavioral and physiological endpoints of hormone action are altered by these treatments as well.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brooke Middlebrook and Matthew Riportella for their technical assistance and Kristin Olesen and Nafissa Ismail for helpful comments on the manuscript. We also thank Golien Safain, Kelly Goodwin, Mihoko Yamamoto, R. Charles Lawrence, Gila Ghavami, Stefanie Pietras, Alina Catrinoiu, and Aaron Harman for their help with behavior testing.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS 19327 and MH 67630 and a grant from the Isis Fund of the Society for Women’s Health Research.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online April 16, 2009

Abbreviations: HPA, Hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; LQ, lordosis quotient.

References

- Romeo RD, Wagner CK, Jansen HT, Diedrich SL, Sisk CL 2002 Estradiol induces hypothalamic progesterone receptors but does not activate mating behavior in male hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) before puberty. Behav Neurosci 116:198–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo RD, Richardson HN, Sisk CL 2002 Puberty and the maturation of the male brain and sexual behavior: recasting a behavioral potential. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 26:381–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KM, Richardson HN, Zehr JL, Osetek AJ, Menard TA, Sisk CL 2004 Gonadal hormones masculinize and defeminize reproductive behaviors during puberty in the male Syrian hamster. Horm Behav 45:242–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek LR, Romeo RD, Novak CM, Sisk CL 1997 Actions of testosterone in prepubertal and postpubertal male hamsters: dissociation of effects on reproductive behavior and brain androgen receptor immunoreactivity. Horm Behav 31:75–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo RD, Bellani R, McEwen BS 2005 Stress-induced progesterone secretion and progesterone receptor immunoreactivity in the paraventricular nucleus are modulated by pubertal development in male rats. Stress 8:265–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo RD, Karatsoreos IN, McEwen BS 2006 Pubertal maturation and time of day differentially affect behavioral and neuroendocrine responses following an acute stressor. Horm Behav 50:463–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward IL 1984 The prenatal stress syndrome: current status. Psychoneuroendocrinology 9:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachser N, Kaiser S 1996 Prenatal social stress masculinizes the females’ behaviour in guinea pigs. Physiol Behav 60:589–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski WJ, Vandenbergh JG, Montano MM 1991 Effects of social stress and intrauterine position on sexual phenotype in wild-type house mice (Mus musculus). Physiol Behav 49:117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser S, Kruijver FP, Swaab DF, Sachser N 2003 Early social stress in female guinea pigs induces a masculinization of adult behavior and corresponding changes in brain and neuroendocrine function. Behav Brain Res 144:199–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris AL, Ramaley JA 1974 Adrenal-gonadal relations and fertility: the effects of repeated stress upon the adrenal rhythm. Neuroendocrinology 15:126–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris A, Kelly P, Ramaley JA 1973 Effects on short-term stress upon fertility. II. After puberty. Fertil Steril 24:546–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paré WP, Glavin GB 1986 Restraint stress in biomedical research: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 10:339–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glavin GB, Paré WP, Sandbak T, Bakke HK, Murison R 1994 Restraint stress in biomedical research: an update. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 18:223–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal MM, Swarts HJ, Wiegant VM, Mattheij JA 1995 Effect of restraint stress on the preovulatory luteinizing hormone profile and ovulation in the rat. Eur J Endocrinol 133:347–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronson FH, Marsteller FA 1985 Effect of short-term food deprivation on reproduction in female mice. Biol Reprod 33:660–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong KH, Jacobson L, Widmaier EP, Majzoub JA 1999 Normal suppression of the reproductive axis following stress in corticotropin-releasing hormone-deficient mice. Endocrinology 140:1702–1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton GD, Bronson FH 1985 Food restriction and reproductive development in wild house mice. Biol Reprod 32:773–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton GD, Bronson FH 1986 Food restriction and reproductive development: male and female mice and male rats. Am J Physiol 250:R370–R376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronson FH 1988 Effect of food manipulation on the GnRH-LH-estradiol axis of young female rats. Am J Physiol 254:R616–R621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drickamer LC 1990 Environmental factors and age of puberty in female house mice. Dev Psychobiol 23:63–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R 2001 Cytokine-induced sickness behavior: where do we stand? Brain Behav Immun 15:7–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugero KD, Moberg GP 2000 Summation of behavioral and immunological stress: metabolic consequences to the growing mouse. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 279:E44–E49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinedi E, Suescun MO, Hadid R, Daneva T, Gaillard RC 1992 Effects of gonadectomy and sex hormone therapy on the endotoxin-stimulated hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis: evidence for a neuroendocrine-immunological sexual dimorphism. Endocrinology 131:2430–2436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marriott LK, McGann-Gramling KR, Hauss-Wegrzyniak B, Sheldahl LC, Shapiro RA, Dorsa DM, Wenk GL 2007 Brain infusion of lipopolysaccharide increases uterine growth as a function of estrogen replacement regimen: suppression of uterine estrogen receptor-α by constant, but not pulsed, estrogen replacement. Endocrinology 148:232–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroche J, Gasbarro L, Herman JP, Blaustein JD 2009 Reduced behavioral response to gonadal hormones in mice shipped during the peripubertal/adolescent period. Endocrinology 150:2351–2358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhees RW, Al-Saleh HN, Kinghorn EW, Fleming DE, Lephart ED 1999 Relationship between sexual behavior and sexually dimorphic structures in the anterior hypothalamus in control and prenatally stressed male rats. Brain Res Bull 50:193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudwa AE, Rissman EF 2003 Double oestrogen receptor α and β knockout mice reveal differences in neural oestrogen-mediated progestin receptor induction and female sexual behaviour. J Neuroendocrinol 15:978–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani SK, Allen JM, Lydon JP, Mulac-Jericevic B, Blaustein JD, DeMayo FJ, Conneely O, O'Malley BW 1996 Dopamine requires the unoccupied progesterone receptor to induce sexual behavior in mice. Mol Endocrinol 10:1728–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JF, Karelus K, Felicio LS, Johnson TE 1990 Genetic influences on the timing of puberty in mice. Biol Reprod 42:649–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neigh GN, Samuelsson AR, Bowers SL, Nelson RJ 2005 3-Aminobenzamide prevents restraint-evoked immunocompromise. Brain Behav Immun 19:351–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss AK, Pyter LM, Neigh GN, Nelson RJ 2004 Nyctohemeral differences in response to restraint stress in CD-1 and C57BL/6 mice. Physiol Behav 80:441–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinedi E, Chisari A, Pralong F, Gaillard RC 1997 Sexual dimorphism in the mouse hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function after endotoxin and insulin stresses during development. Neuroimmunomodulation 4:77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song DK, Suh HW, Huh SO, Jung JS, Ihn BM, Choi IG, Kim YH 1998 Central GABAA and GABAB receptor modulation of basal and stress-induced plasma interleukin-6 levels in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 287:144–149 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masotto C, Caspani G, De Simoni MG, Mengozzi M, Scatturin M, Sironi M, Carenzi A, Ghezzi P 1992 Evidence for a different sensitivity to various central effects of interleukin-1β in mice. Brain Res Bull 28:161–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft TK, DeVries AC 2006 Role of IL-1 in poststroke depressive-like behavior in mice. Biol Psychiatry 60:812–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armario A, Hernández J, Bluethmann H, Hidalgo J 1998 IL-6 deficiency leads to increased emotionality in mice: evidence in transgenic mice carrying a null mutation for IL-6. J Neuroimmunol 92:160–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson ML, Edwards DA 1971 Experiential and strain determinants of the estrogen-progesterone induction of sexual receptivity in spayed female mice. Horm Behav 2:299–305 [Google Scholar]

- Rissman EF, Early AH, Taylor JA, Korach KS, Lubahn DB 1997 Estrogen receptors are essential for female sexual receptivity. Endocrinology 138:507–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Catanzaro D, Lee PC, Kerr TH 1985 Facilitation of sexual receptivity in female mice through blockade of adrenal 11β-hydroxylase. Horm Behav 19:77–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]