Abstract

We used proliferating primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells expressing the recombinant human LH/choriogonadotropin (CG) receptor (LHR) to test the hypothesis that activation of this receptor inhibits apoptosis. We also compared the effects of LH/CG with epidermal growth factor (EGF) and IGF-I because these have been previously shown to stimulate proliferation and/or inhibit apoptosis in Leydig cells. Human CG (hCG), EGF, and IGF-I stimulated the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Akt in primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells. These three hormones also robustly stimulated thymidine incorporation and inhibited drug-induced apoptosis. Using selective inhibitors of ERK1/2 (UO126) or Akt phosphorylation (LY294002), we show that the ERK1/2 and Akt cascades are both involved in the hCG- and EGF-dependent proliferation of Leydig cells, but only the ERK1/2 cascade is involved in their antiapoptotic actions. The same strategy showed that the proliferative and antiapoptotic actions of IGF-I are mediated entirely by the Akt pathway. These results show that activation of the LHR inhibits apoptosis in Leydig cells and that it does so through stimulation of the ERK1/2 pathway.

Activation of the LHR inhibits apoptosis in immature rat Leydig cells, and this effect is mediated by ERK1/2.

The ability of the LH/choriogonadotropin (CG) receptor (LHR) to stimulate the proliferation of the postnatal population of Leydig cells was initially recognized by injecting human CG (hCG) into rats (1,2,3) and later confirmed by the phenotype of genetically modified mouse models. Thus, mice lacking GnRH as well as mice with targeted deletion of the LHR exhibit Leydig cell hypoplasia (4,5,6), whereas transgenic mice overexpressing hCG or LH develop Leydig cell adenomas (7). Similarly, 46XY individuals harboring naturally occurring germline or somatic mutations of the hLHR display Leydig cell hyperplasia or Leydig cell adenomas, respectively, whereas those harboring germline inactivating mutations display Leydig cell hypoplasia (reviewed in Refs. 8 and 9).

There is a growing body of evidence that implicates the LHR as a regulator of mitogenic signaling cascades in Leydig cells. The phosphorylation of ERK1/2 is increased by LH/CG in primary cultures of progenitor or immature rat Leydig cells (10,11) and in MA-10 Leydig tumor cells (12,13,14,15). Although the LHR-regulated ERK1/2 cascade is clearly important in the regulation of steroidogenesis in Leydig cells (10,16,17), our recent data suggest that this pathway is also involved in their proliferation (11). The effects of LH/CG on Leydig cell apoptosis and on the stimulation of the Akt pathway, another important regulator of cell multiplication and survival (18,19,20), have not been explored in detail. Therefore, in the experiments presented here, we used primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells to test the hypothesis that LH/CG promotes the survival of Leydig cells by stimulation of ERK1/2 and/or Akt phosphorylation. We also compared the effects of LH/CG with those of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and IGF-I because EGF has been shown to stimulate DNA synthesis (11), whereas IGF-I has been shown to inhibit apoptosis (19,21) in immature rodent Leydig cells.

Materials and Methods

Isolation, culture, and infection of Leydig cells

Immature rat Leydig cells were isolated from testes of 35-d-old rats by collagenase dispersion and Percoll gradient centrifugation as described earlier (11). The procedures used were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Iowa.

Cells (2–3 × 105) were plated in 1 ml DMEM/F12 with 15 mm HEPES, 0.1% BSA, and 100 μg/ml gentamicin (pH 7.4) in 12-well plates coated with gelatin. One day after plating, the culture medium was changed to DMEM/F12 supplemented with 15 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 2% newborn calf serum, and 100 μg/ml gentamicin (serum-containing medium). Two days after plating, some wells were used to determine cell density (11). The rest were washed twice with BSA-containing medium and incubated with 200 multiplicity of infection (number of viable viral particles per cell) of the recombinant adenovirus coding for the human LHR (Ad-hLHR) for 2 h at 37 C as described (11). The infection was stopped by replacing the virus-containing solution with serum-containing medium. The following day, the medium was changed again to BSA-containing medium. All experiments were initiated 4 d after plating (2 d after infection). At this point, most of the cells stain positive for 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, and about 65% express the hLHR (11). The hLHR density (measured by [125I]hCG binding) corresponds to 25,000–40,000 receptors per cell (11), which is within the range of densities of LHR (10,000–40,000 receptors per cell) expressed in freshly isolated immature or adult rat Leydig cells (22,23).

The concentrations of hCG, EGF, or IGF-I used (100 ng/ml) are the lowest concentrations that elicit maximal effects (data not shown). Also, when time courses are not shown, the times chosen are the optimal times for each measurement. Lastly, the concentrations of inhibitors used were also chosen empirically as the lowest concentrations that elicit a maximal inhibitory effect (11).

Western blots

The methods used to prepare lysates and have been described (13,24,25). Primary antibodies to phospho-ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA sc-7383 and sc-153, respectively) and phospho-Akt and total Akt (Cell Signaling Biotechnology, Beverly, MA; catalog nos. 9271 and 9272, respectively) were used at dilutions of 1/5,000, 1/10,000, 1/1,000, and 1/1,000, respectively. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antimouse and antirabbit secondary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1/3000. All immune complexes in the Western blots were ultimately visualized using the Super Signal West Femto maximum sensitivity detection system (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL) and exposed to film or captured digitally with a Kodak digital imaging system (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). The quantitative analysis presented was done with the digital imaging system. Quantitation of the digital images captured using this system is more accurate because of its wider dynamic range that makes signal saturation less likely. In addition, the software included with this imaging system can readily determine whether an image is saturated, thus preventing its quantitation.

[3H]Thymidine incorporation

On d 4 (see above), the medium was changed again to BSA-containing medium, and the indicated hormones were added. Twenty hours later, [3H-methyl]thymidine (2 μCi/ml) was added, and the incubation was continued for another 4 h. The cells were then washed twice with 1 ml cold 20 mm HEPES and 150 mm NaCl (pH 7.4) and incubated with 500 μl freshly prepared cold 10% trichloroacetic acid for 30 min on ice. After aspiration, the cells were washed twice with 500 μl of the same solution, dissolved in 500 μl 0.5 N NaOH, neutralized with 125 μl 2 N HCl, mixed with 10 ml BudgetSolve, and counted in a liquid scintillation counter.

Apoptosis

On d 4 (see above), the medium was changed again to BSA-containing medium, and the cells were incubated with 100 ng/ml hCG, EGF, or IGF-I. After 2 h, apoptosis was induced by adding 0.5 μm staurosporine, and the incubation was continued for another 2 h.

Apoptotic cells were initially visualized by their ability to bind Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated annexin V during a 30-min incubation at room temperature. This assay was performed using a commercially available kit (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA; catalog item V13241) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After binding the fluorescent annexin V, the cells were fixed (15 min at room temperature) with 4% paraformaldehyde and then incubated for 5 min with a 10 mg/ml solution of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to stain the nuclei. The wells were observed and photographed using a fluorescent microscope with the appropriate filters (green for annexin V and blue for DAPI) and a magnification of ×100. Only the merged images are shown.

A quantitative assessment of apoptosis was accomplished by measuring the activity of caspase 3/7 (26,27,28). Cell lysates were prepared in a lysis buffer containing 1% Nonidet P40, 20 mm HEPES, 0.15 m NaCl (pH 7.4). Fifty-microliter aliquots of the clarified lysates containing 10 μg protein were mixed with 35 μl of the above-mentioned buffer, 10 μl 100 mm dithiothreitol, and 5 μl of a 1 mm solution [prepared in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)] of a caspase 3/7 tetrapeptide substrate (DEVD). This caspase substrate is acetylated at the N terminus and conjugated to 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC) at the C terminus. The enzymatic reaction was allowed to proceed overnight at room temperature, and the fluorescent product (AMC) was measured using a fluorescent microplate reader using an excitation wavelength of 360 ± 20 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 ± 20 nm. The fluorescence of blank wells containing lysis buffer instead of cell lysates was subtracted from all values obtained.

Statistical analysis

ANOVA with Dunnet’s post test was used for multiple comparisons with a control group, and ANOVA with Tukey’s post test was used for multiple comparisons among groups. These analyses were performed using the InStat software package from GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA). In all cases, statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

Hormones and supplies

Purified hCG (CR-127) was purchased from Dr. A. Parlow of the National Hormone and Pituitary Agency (Torrance, CA). Purified recombinant hCG was kindly provided by Ares Serono (Boston, MA). AG1478, AG43, PP2, and PP3, were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). UO126 and LY294002 were from Tocris (Ellisville, MO) or Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Cell culture medium was obtained from Invitrogen, and cell culture plastic ware was from Corning (Corning, NY). [3H-Methyl]Thymidine (20 Ci/mmol) was from PerkinElmer (Norwalk, CT). Ac-DEVD-AMC and staurosporine were from Biomol. All other chemicals were obtained from commonly used suppliers.

Results

hCG stimulates the phosphorylation of Akt in Leydig cells

All experiments presented here were done using a proliferating population of immature rat Leydig cells expressing the hLHR and maintained in culture for several days (11). The endogenous LHR is rapidly lost when freshly isolated Leydig cells are placed in culture, but it can be replaced by expression of the recombinant hLHR (11). When care is taken to express the recombinant hLHR at a density that is comparable to that of the endogenous LHR (10,000–40,000 receptors per cell), the immature rat Leydig cell cultures respond to hCG with an increase in cAMP, inositol phosphates, and testosterone synthesis as well as an increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation (11). Moreover, hCG stimulates DNA synthesis and promotes at least one round of cell division (11).

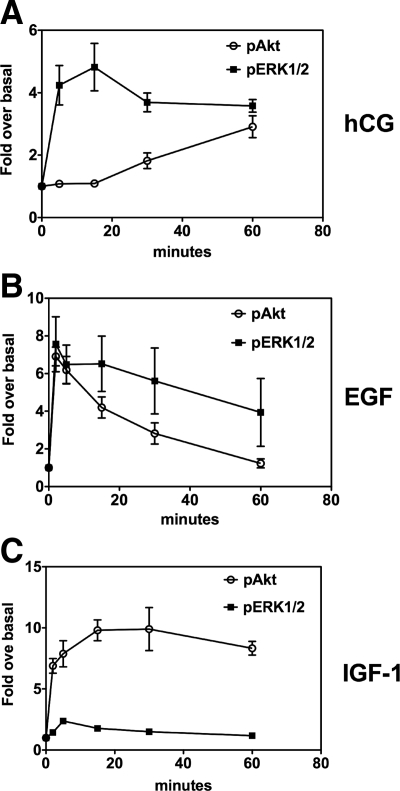

The results presented in Fig. 1A show that hCG stimulates the phosphorylation of Akt after a lag of 15–30 min. The maximal effect is attained after 60–120 min. This time course contrasts with that of ERK1/2 phosphorylation, which attains a maximum within 5–15 min after addition of hCG and remains elevated for at least 60 min. EGF also stimulates Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a rapid and transient fashion (Fig. 1B). Lastly, IGF-I was previously reported to stimulate Akt phosphorylation in Leydig cells (19,21), and we readily confirmed this observation (Fig. 1C). We also showed that IGF-I stimulates the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Quantitation of the effects of hCG on the phosphorylation of Akt in primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells. Primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells were incubated with hCG (A), EGF (B), or IGF-I (C) each at 100 ng/ml for the times indicated. The levels of phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) and ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) as well as total Akt and ERK1/2 were ascertained by Western blotting with the appropriate antibodies and quantitated as described in Materials and Methods. For each kinase, the phosphoprotein signal was corrected for the total protein signal, and this value was defined as 1 for the zero time point (i.e. no hormone added). All other times points are expressed relative to this basal level of phosphorylation. Each point is the mean ± sem of at least three independent experiments.

The hCG-induced phosphorylation of Akt depends on the activation of the Src family of kinases

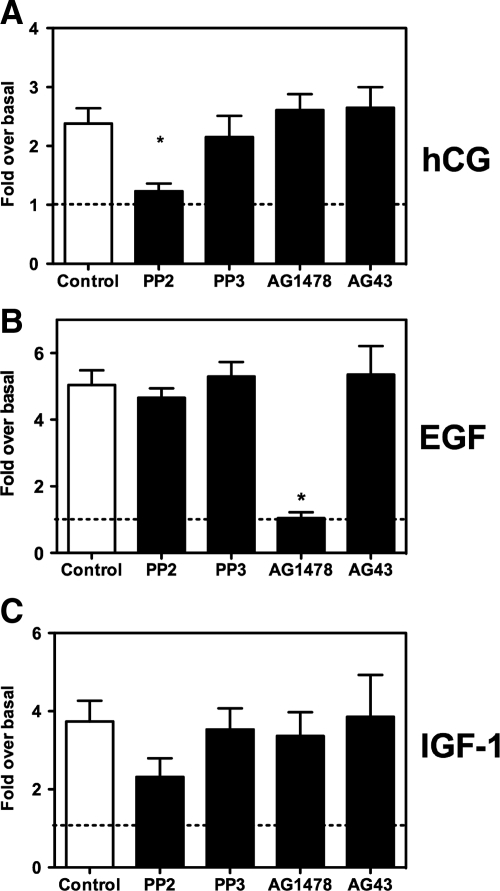

The results presented in Fig. 2A show that the hCG-induced phosphorylation of Akt is blocked by PP2, an inhibitor of the Src family of kinases (SFK) but not by AG1478, an inhibitor of the EGF receptor (EGFR) kinase. In contrast, the EGF-induced phosphorylation of Akt is completely blocked by AG1478 but is not affected by PP2 (Fig. 2B). As expected, the inactivate analogs of these two compounds (PP3 and AG43) were without effect. None of these inhibitors had an effect on the ability of IGF-I to enhance the phosphorylation of Akt (Fig. 2C). This was expected because IGF-I stimulates Akt phosphorylation using the insulin receptor substrate family of proteins as intermediates, and this pathway is insensitive to any of the inhibitors used in Fig. 2 (29). The phosphorylation of Akt in the IGF-I-stimulated and PP2-treated cells always tended to be lower than the controls, but this reduction never attained statistical significance (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Effects of several inhibitors on the hCG-, EGF-, or IGF-I-induced Akt phosphorylation in primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells. Primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells were preincubated for 30 min with DMSO (control), PP2 (10 μm), PP3 (10 μm), AG1478 (1 μm), or AG43 (1 μm) as indicated. The phosphorylation of Akt was then measured at the end of a 60-min incubation with 100 ng/ml hCG (A), a 5-min incubation with 100 ng/ml EGF (B), or a 15-min incubation with 100 ng/ml IGF-I (C). The phospho-Akt signal was corrected for the total Akt signal, and this value was defined as 1 for the cells incubated without hormone. All other values (mean ± sem of three to five independent experiments) are expressed relative to this basal level of phosphorylation, which is indicated by the dashed horizontal line. *, Significant differences (P < 0.05, ANOVA with Dunnet’s post test) when compared with cells incubated with DMSO only (control, white bar).

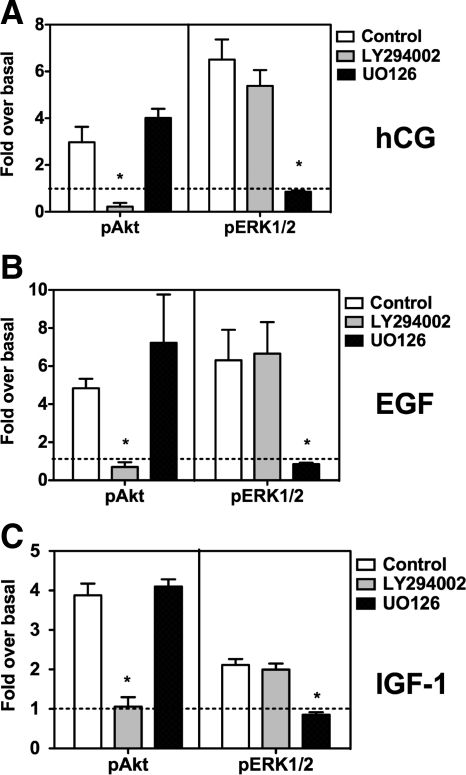

To assess the potential involvement of the ERK1/2 and Akt pathways on the proliferation and survival of Leydig cells, we had to find conditions to selectively inhibit each of these pathways. We thus assessed the selectivity of two widely used inhibitors (UO126 and LY294002) by measuring ERK1/2 and Akt phosphorylation in Leydig cell cultures stimulated with hCG, EGF, or IGF-I. Figure 3 shows that regardless of the stimulus used, LY294002 effectively inhibited Akt phosphorylation without affecting ERK1/2 phosphorylation, whereas UO126 inhibited ERK1/2 phosphorylation without affecting Akt phosphorylation.

Figure 3.

Effects of UO126 and LY294002 on the hCG-, EGF-, or IGF-I-induced phosphorylation of Akt or ERK1/2 in primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells. Primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells were preincubated for 30 min with DMSO (control), LY294003, or UO126 (each at 10 μm) as indicated. The phosphorylation of Akt (pAkt, left panels) was then measured at the end of a 60-min incubation with 100 ng/ml hCG (A), a 5-min incubation with 100 ng/ml EGF (B), or a 15-min incubation with 100 ng/ml IGF-I (C). The phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (pERK1/2, right panels) was measured at the end of a 15-min incubation with 100 ng/ml hCG (A), a 5-min incubation with 100 ng/ml EGF (B), or a 15-min incubation with 100 ng/ml IGF-I (C). For each kinase, the phosphoprotein signal was corrected for the total protein signal, and this value was defined as 1 for the cells treated without hormones or inhibitors. All other values are expressed relative to this basal level of phosphorylation, which is shown by the dashed horizontal line. Each point is the mean ± sem of at least three to five independent experiments. *, Significant differences (P < 0.05, ANOVA with Dunnet’s post test) when compared with cells incubated with DMSO only (control, white bar in each panel).

The effects of hCG on the proliferation of Leydig cells are mediated by the ERK1/2 and Akt pathways

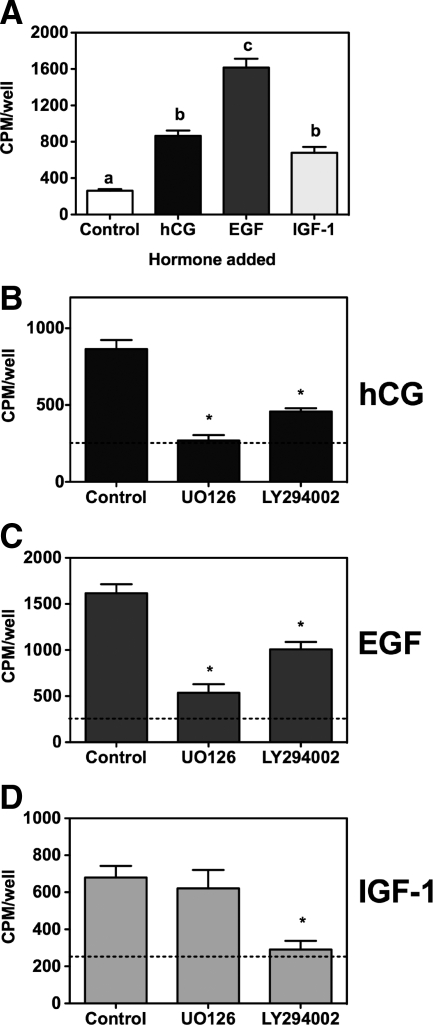

The data presented in Fig. 4A show that hCG, EGF, and IGF-I stimulate DNA synthesis in Leydig cells. IGF-I is as effective as hCG, but EGF is more effective than either hCG or IGF-I (1). [When added together at maximally effective concentrations, the effects of hCG, EGF, or IGF appeared to be synergistic rather than additive (data not shown)]. The data presented in Fig. 4, B–D, show that addition of UO126 inhibits the effects of hCG and EGF on DNA synthesis but not that of IGF-I. In contrast, addition of LY294002 leads to a partial inhibition of Leydig cell DNA synthesis when stimulated with hCG or EGF and a more complete inhibition when stimulated with IGF-I.

Figure 4.

Effects of UO126 and LY294002 on the proliferative effects of hCG, EGF, or IGF-I on primary cultures of rat Leydig cells. A, Primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells were incubated with buffer only, hCG, EGF, or IGF-I (each at 100 ng/ml) for 24 h as indicated. The cells were labeled with [3H]thymidine during the last 4 h of this incubation, and the radioactivity incorporated into DNA was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar is the mean ± sem of five to 10 independent experiments. The values of the bars marked by the different letters (a, b, c) are significantly different from each other (P < 0.05, ANOVA with Tukey’s post test). B–D, Primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells were preincubated for 30 min with DMSO only (control), UO126, or LY294002 (each at 10 μm) as indicated. hCG (B), EGF (C), or IGF-I (D) (each at 100 ng/ml) was added for 24 h. The cells were labeled with [3H]thymidine during the last 4 h of this incubation, and the radioactivity incorporated into DNA was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar is the mean ± sem of five to eight independent experiments. *, Significant differences (P < 0.05, ANOVA with Dunnet’s post test) when compared with cells incubated with DMSO only (control). The dashed horizontal line shows the level of [3H]thymidine incorporated in cells incubated without inhibitors or hormones.

hCG is an antiapoptotic agent for Leydig cells, and this effect is mediated by the ERK1/2 pathway

In this last series of experiments, we addressed the possibility that hCG promotes the survival of Leydig cells and attempted to determine which of the two kinase cascades (ERK1/2 and Akt) mediate this putative antiapoptoic effect. We also included EGF in these experiments because it stimulates ERK1/2 and Akt and is a potent mitogen for Leydig cells (Figs. 1, 2, and 5 and Ref. 11). Lastly, IGF-I was included as a control because others have shown that it inhibits apoptosis in short-term cultures of Leydig cells using the Akt pathway as an intermediate (19).

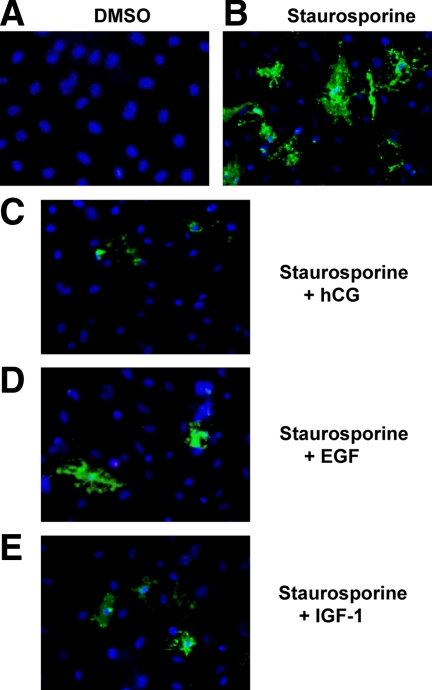

Figure 5.

hCG, EGF, or IGF-I have antiapoptotic effects on primary cultures of rat Leydig cells. A and B, Primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells were incubated with DMSO or staurosporine (0.5 μm final concentration) for 2 h before detection of the binding of Alexa488-conjugated annexin V (green) or detection of the cell nuclei with DAPI (blue). C–E, Primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells were preincubated with hCG (B), EGF (C), or IGF-I (D), each at 100 ng/ml, for 2 h. Staurosporine (0.5 μm final concentration) was then added (without removing the hormones) to all cultures for 2 h, and the cells were stained as described above. The results of a representative experiment are shown.

We first assessed the level of apoptosis in the primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells using fluorescent annexin V. Because we wanted to examine a potential antiapoptotic effect and because apoptotic cells were basically undetectable in the primary cultures of Leydig cells (Fig. 5A), we sought to find a way to reliably induce apoptosis in these cultures. Apoptosis of Leydig cells has been previously induced with glucocorticoids (30) or H2O2 (31), but in our hands, the extent of apoptosis induction by these compounds was rather low and variable (not shown). We thus tried more commonly used apoptosis-inducing drugs such as staurosporine and TPEN (32). Although both of these were effective apoptotic agents for Leydig cells, we eventually settled on a 2-h incubation with 0.5 μm staurosporine as a reliable treatment to induce apoptosis (Fig. 5, A and B).

Annexin V binding assays in Leydig cell cultures treated with staurosporine alone or together with hCG, EGF, or IGF-I suggested that these three hormones decreased staurosporine-induced apoptosis (Fig. 5). Because annexin V binding is difficult to quantitate, however, we turned to an enzymatic assay that measures the activation of caspase-3 and -7 as an indicator of apoptosis (26,28,32,33). These data are presented in Fig. 6A and show that a 2-h incubation of Leydig cell cultures with 0.5 μm staurosporine increases caspase-3/7 activity about 3-fold. When the cells are preincubated with hCG, EGF, or IGF-I for 2 h before adding staurosporine, however, the increase in the activity of caspase-3/7 was blocked partially or completely (Fig. 6A). Thus, in agreement with the qualitative data obtained using annexin V binding (Fig. 5), the quantitative caspase-3/7 activity results (Fig. 6A) show that hCG, EGF, and IGF-I block staurosporine-induced apoptosis in Leydig cells. The 2-h preincubation with the different hormones was chosen because this was the minimum time required to maximally inhibit apoptosis.

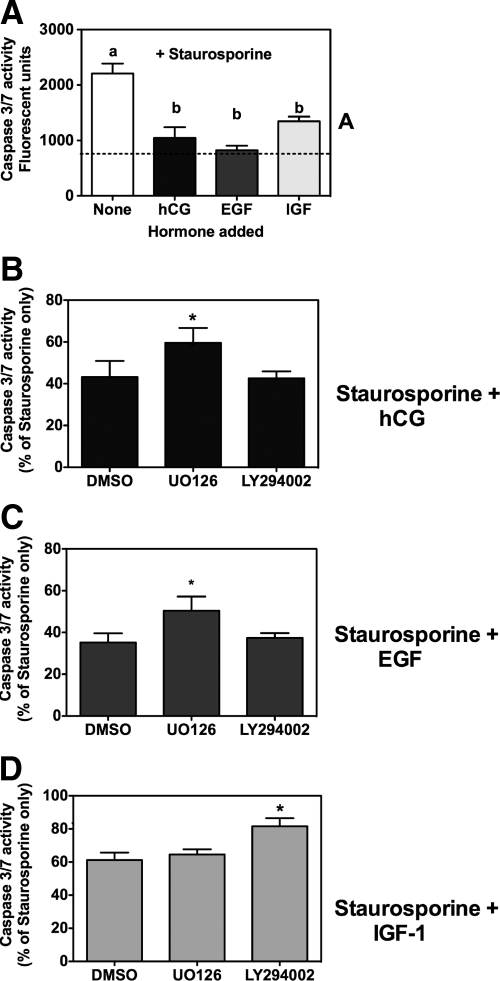

Figure 6.

Effects of UO126 and LY294002 on the antiapoptotic effects of hCG, EGF, or IGF-I on primary cultures of rat Leydig cells. A, Primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells were preincubated with buffer only, hCG, EGF, or IGF-I (each at 100 ng/ml) for 2 h as indicated. Staurosporine (0.5 μm final concentration) was then added (without removing the hormones) for 2 h, and the cells were lysed and used to measure the activity of caspase 3/7 as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar is the mean ± sem of five independent experiments. The values of the bars marked by the different letters (a and b) are significantly different from each other (P < 0.05, ANOVA with Tukey’s post test). The dashed line indicates the activity of caspase 3/7 in cells incubated without staurosporine or hormones. B–D, Primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells were preincubated for 30 min with DMSO (control), UO126, or LY294002 (each at 10 μm) as indicated. hCG (B), EGF (C), or IGF-I (D) was added (without removing the previous additions), each at 100 ng/ml, and the incubation was continued for 2 h. Finally, staurosporine (0.5 μm final concentration) was added to all cultures (without removing the hormones or inhibitors) and the incubation continued for another 2 h. The cells were lysed and used to measure the activity of caspase 3/7 as described in Materials and Methods. In each panel, the activity of caspase 3/7 is expressed as a percentage of the activity of caspase 3/7 detected in cells incubated with staurosporine alone. Each bar is the mean ± sem of five independent experiments. *, Significant differences (P < 0.05, ANOVA with Dunnet’s post test) when compared with same cells incubated with DMSO only (control).

To determine the pathways that mediate the antiapoptotic effect of these three hormones, we used a protocol that involved three sequential incubations. The cells were first incubated with vehicle only (DMSO), an inhibitor of ERK1/2 (UO126), or an inhibitor of Akt phosphorylation (LY294002). The cells were then incubated with hCG (Fig. 6B), EGF (Fig. 6C), or IGF-I (Fig. 6D) without removing the inhibitors, and finally, all cells were incubated with staurosporine (without removing the inhibitors or the hormones) to induce apoptosis. If ERK1/2 or Akt phosphorylation mediates these antiapoptotic effects, then UO126 or LY294002 should restore the ability of staurosporine to induce apoptosis. Figure 6, B and C, shows that UO126 partially restored the apoptotic effects of staurosporine in hCG- or EGF-treated cells, but LY294002 did not. Conversely, LY294002 partially restored the ability of staurosporine to induce apoptosis in IGF-I-treated cells, but UO126 did not (Fig. 6D). The results presented in Fig. 6 also show that the kinase inhibitors reverse the antiapoptotic effects of hCG, EGF, or IGF-I by 30–50%. This partial reversal could be due to the nature of the assays used or to the involvement of additional pathways in the antiapoptotic effects of hCG, EGF, or IGF-I.

Discussion

There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that LH is an important proliferative signal for Leydig cells during postnatal development (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9). It is also likely that LH inhibits apoptosis in Leydig cells, but this possibility has not been examined in detail. Thus, the experiments presented here were designed to test the hypothesis that LH/CG inhibits Leydig cell apoptosis and to identify the signaling pathways that may contribute to this effect. Because activation of the LHR in immature Leydig cells stimulates the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (this paper and Ref. 11) and Akt (this paper) and these pathways can affect apoptosis in other cells (18,20,34,35), we concentrated on examining the involvement of these two kinase cascades in proliferation and apoptosis of immature rat Leydig cells.

All experiments were done using a proliferating population of immature rat Leydig maintained in culture for several days (11). These cells rapidly lose their endogenous LHR when placed in culture, but their responsiveness to LH/CG can be maintained by infecting with an adenovirus expressing the hLHR (11). When care is taken to express the recombinant hLHR at a density that is comparable to that of the endogenous LHR (10,000–40,000 receptors per cell) (11), the Leydig cell cultures respond to hCG with an increase in the synthesis of cAMP, inositol phosphates, and testosterone and an increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation (11). In addition, hCG stimulates DNA synthesis and at least one cell division (11). Although these experiments can also be done using cultures of progenitor rat Leydig cells, we have found very little difference in the responses of the progenitor or immature Leydig cells (11). We prefer to use immature cells because their lineage can be readily established by their ability to synthesize testosterone. Moreover, because we are studying the actions of LH, it is important that the Leydig cells be isolated during a postnatal period when the levels of LH in the serum are increasing (36).

Activation of the LHR increases the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in Leydig cells using a combination of intracellular and intercellular pathways that ultimately converge at the level of Ras activation (11,13,14,15). The intracellular pathway is cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) dependent, whereas the intercellular pathway is cAMP independent, and relies on the release of EGF-like growth factors that then transactive the EGFR in a paracrine/autocrine fashion (14,15). This intercellular pathway is initiated by an arrrestin-3-dependent activation of Fyn, a member of the SFK (15).

The canonical pathway for Akt phosphorylation depends on the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (18,20). Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is in turn activated by growth factor receptors such as those for EGF and IGF-I or by Gβγ liberated as a consequence of activation of G protein-coupled receptors (18,20). Although we have not performed a complete characterization of the pathways by which the LHR enhances Akt phosphorylation, the data presented show that this pathway is dependent on the SFK but not the EGFR (Fig. 2). This stands in contrast with the LHR-dependent activation of ERK1/2 in the Leydig cells, a process that is dependent on both the SFK and the EGFR (11,13,14). The potential involvement of cAMP/PKA on the LHR-dependent activation of Akt in Leydig cells is unclear and will require future experimentation. Our initial studies (not presented) have shown that PKA-selective cAMP analogs enhance Akt phosphorylation, but H89, a compound that is routinely used to inhibit the actions of PKA (12), does not inhibit the LH/CG-induced phosphorylation of Akt. These results are similar to those of LH/CG or FSH on the phosphorylation of Akt in granulosa cells (37,38,39). For example, the SFK seem to mediate this effect of FSH (38,39), but it is not known whether the same is true for LH/CG. Similarly, addition of cAMP analogs stimulates the phosphorylation of Akt in granulosa cells, but inhibitors of PKA do not inhibit the FSH-induced activation of this kinase (38).

The effects of LH/CG on the proliferation of Leydig cells in intact rats and in cell culture have been previously documented (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,11), and some of those results are reproduced here (Fig. 4). The new data presented here clearly show that activation of the LHR also inhibits apoptosis in Leydig cells (Figs. 5 and 6).

IGF-I has been shown to stimulate the proliferation of Leydig cells in intact mice (21) and to decrease apoptosis in short-term cultures of immature rat Leydig cells (19). The results presented here confirm these observations (Figs. 4–6). EGF or other members of the EGF family have been shown to activate proliferative pathways in the testes of neonatal mice (40) and to enhance DNA synthesis in Leydig cell cultures (11,41,42). The results presented here confirm these observations but also show, for the first time, that EGF inhibits apoptosis in Leydig cells (Figs. 4–6).

Because we can readily show that hCG, EGF, and IGF-I stimulate DNA synthesis and inhibit apoptosis in primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells and that these hormones stimulate the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Akt, we can now determine which of the two cascades is involved in the proliferative and antiapoptotic effects of these three hormones. This question was addressed here by using selective inhibitors of ERK1/2 or Akt phosphorylation. Importantly, our data show that the ERK1/2 and Akt cascades mediate the proliferative and prosurvival actions of hCG, EGF, and IGF-I, but their relative involvement depends on the hormone used. The proliferative actions of hCG are mediated by ERK1/2 and Akt, but its antiapoptotic actions are mediated only by ERK1/2. The same is true for EGF. The proliferative and antiapoptotic effects of IGF-I are, however, mediated only by Akt. Because all three hormones activate ERK1/2 and Akt phosphorylation, it is unclear why these pathways do not play the same role in their proliferative and antiapoptotic actions. One possible explanation is that the duration and/or magnitude of the activation of each pathway dictate their relative involvement in the proliferative and antiapoptotic actions of hCG, EGF, and IGF-I. It is possible then that IGF-I uses only the Akt pathway because the phosphorylation of Akt is always higher than the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, whereas hCG and EGF may use Akt and ERK1/2 because the magnitude of stimulation of both pathways is similar (Fig. 1). Because the activation of Akt is complex and requires more than one phosphorylation event (43), it is also possible that Akt is fully activated in response to IGF-I but only partially activated in response to hCG and EGF. Likewise, it is already known that the time course of phosphorylation or ERK1/2 is important for its actions. For example, in PC12 cells, a transient phosphorylation of ERK/12 causes proliferation, whereas a sustained phosphorylation causes differentiation (reviewed in Ref. 35). Similarly, in granulosa cells, a sustained activation of ERK1/2 is associated with a decrease in aromatase expression, whereas a transient activation is not (44,45,46).

In summary, the studies presented here show that activation of the LHR inhibits apoptosis in immature rat Leydig cells, and this effect is mediated by ERK1/2. We also show that the LHR-provoked activation of Akt, together with the activation of ERK1/2, mediates the proliferative effects of the LHR on Leydig cells. Our data thus suggest that the stimulatory effects of LH on the adult Leydig cell population are due to an increase in Leydig cell proliferation and a decrease in Leydig cell apoptosis and that the ERK1/2 and Akt pathways are essential mediators of these actions of LH.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA-40629).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

First Published Online April 30, 2009

Abbreviations: AMC, 7-Amino-4-methylcoumarin; CG, choriogonadotropin; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, EGF receptor; LHR, LH/CG receptor; SFK, Src family of kinases.

References

- Christensen AK, Peacock KC 1980 Increase in Leydig cell number in testes of adult rats treated chronically with an excess of human chorionic gonadotropin. Biol Reprod 22:383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teerds KJ, De Rooji DG, Rommerts FF, van den Hurk R, Wensing CJ 1989 Stimulation of the proliferation and differentiation of Leydig cell precursors after the destruction of existing Leyidg cells with ethane dimethyl sulphonate (EDS) can take place in the abscene of LH. J Androl 10:472–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teerds KJ, De Rooij DG, Rommerts FF, Wensing CJ 1988 The regulation of the proliferation and differentiation of rat Leydig cell precursor cells after EDS administration or daily hCG treatments. J Androl 9:343–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PJ, O'Shaughnessy PJ 2001 Role of gonadotropins in regulating numbers of Leydig and Sertoli cells during fetal and postnatal development in mice. Reproduction 122:227–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang FP, Poutanen M, Wilbertz J, Huhtaniemi I 2001 Normal prenatal but arrested postnatal sexual development of luteinizing hormone receptor knockout (LuRKO) mice. Mol Endocrinol 15:172–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei ZM, Mishra S, Zou W, Xu B, Foltz M, Li X, Rao CV 2001 Targeted disruption of luteinizing hormone/human chorionic gonadotropin receptor gene. Mol Endocrinol 15:184–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahtiainen P, Rulli S, Pakarainen T, Zhang F-P, Poutanen M, Huhtaniemi I 2007 Phenotypic characterisation of mice with exaggerated and missing LH/hCG action. Mol Cell Endocrinol 260–262:255–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Themmen APN 2005 An update of the pathophysiology of human gonadotrophin subunit and receptor gene mutations and polymorphisms. Reproduction 130:263–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piersma D, Verhoef-Post M, Berns EM, Themmen AP 2007 LH receptor gene mutations and polymorphisms: an overview. Mol Cell Endocrinol 260–262:282–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinelle N, Holst M, Söder O, Svechnikov K 2004 Extracellular signal-regulated kinases are involved in the acute activation of steroidogenesis in immature rat Leydig cells by human chorionic gonadotropin. Endocrinology 145:4629–4634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi K, Ascoli M 2007 Lutropin/choriogonadotropin (LH/CG) stimulate the proliferation of primary cultures of rat Leydig cells through a pathway that involves activation of the ERK1/2 cascade. Endocrinology 148:3214–3225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa T, Ascoli M 2003 The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHR)-induced phosphorylation of the extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERKs) in Leydig cells is mediated by a protein kinase A-dependent activation of Ras. Mol Endocrinol 17:2189–2200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi K, Ascoli M 2006 Activation of the lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHR) in MA-10 cells stimulates tyrosine kinase cascades that activate Ras and the extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERK1/2). Endocrinology 147:3419–3427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi K, Ascoli M 2008 A co-culture system reveals the involvement of intercellular pathways as mediators of the lutropin receptor (LHR)-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in Leydig cells. Exp Cell Res 314:25–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galet C, Ascoli M 2008 Arrestin-3 is essential for the activation of Fyn by the luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) in MA-10 cells. Cell Signal 20:1822–1829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaul K, Hammes SR 2008 Cross-talk between G protein-coupled and epidermal growth factor receptors regulates gonadotropin-mediated steroidogenesis in Leydig cells. J Biol Chem 283:27525–27533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocco DM, Wang X, Jo Y, Manna PR 2005 Multiple signaling pathways regulating steroidogenesis and StAR expression: more complicated than we thought. Mol Endocrinol 19:2647–2659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC 2006 The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet 7:606–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colón E, Zaman F, Axelson M, Larsson O, Carlsson-Skwirut C, Svechnikov KV, Söder O 2007 Insulin-like growth factor-I is an important anti-apoptotic factor for rat Leydig cells during postnatal development. Endocrinology 148:128–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazil DP, Yang ZZ, Hemmings BA 2004 Advances in protein kinase B signalling: AKTion on multiple fronts. Trends Biochem Sci 29:233–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Hardy MP 2004 Development of Leydig cells in the insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) knockout mouse: effects of IGF-I replacement and gonadotropic stimulation. Biol Reprod 70:632–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan LX, Hardy MP 1992 Developmental changes in levels of luteinizing hormone receptor and androgen receptor in rat Leydig cells. Endocrinology 131:1107–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Hardy MP, Zirkin BR 2002 Age-related decreases in Leydig cell testosterone production are not restored by exposure to LH in vitro. Endocrinology 143:1637–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa T, Galet C, Ascoli M 2002 MA-10 cells transfected with the human lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (hLHR). A novel experimental paradigm to study the functional properties of the hLHR. Endocrinology 143:1026–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani T, Shiraishi K, Welsh T, Ascoli M 2006 Activation of the lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHR) in MA-10 cells leads to the tyrosine phosphorylation of the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) by a pathway that involves Src family kinases. Mol Endocrinol 20:619–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtu V, Kain SR, Zhang G 1997 Fluorometric and colorimetric detection of caspase activity associated with apoptosis. Anal Biochem 251:98–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaculova A, Zhivotovsky B 2008 Caspases: determination of their activities in apoptotic cells. Methods Enzymol 442:157–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler C, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B 2002 Evaluation of caspase activity in apoptotic cells. J Immunol Methods 265:97–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi A, White MF 2008 Insulin-like signaling, nutrient homeostasis, and life span. Annu Rev Physiol 70:191–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao HB, Tong MH, Hu YQ, You HY, Guo QS, Ge RS, Hardy MP 2003 Mechanisms of glucocorticoid-induced Leydig cell apoptosis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 199:153–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam DK, Misro MM, Chaki SP, Sehgal N 2006 H202 at physiological concentrations modulates Leydig cell function inducing oxidate stress and apoptosis. Apoptosis 11:39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner MO 2000 The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature 407:770–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco RA, Stamm NB, Patel BK 2003 One-step cellular caspase-3/7 assay. Biotechniques 34:1064–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers Gibson T, Xu BE, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH 2001 Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev 22:153–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaul YD, Seger R 2007 The MEK/ERK cascade: from signaling specificity to diverse functions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1773:1213–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee VW, de Kretser DM, Hudson B, Wang C 1975 Variations in serum FSH, LH and testosterone levels in male rats from birth to sexual maturity. J Reprod Fertil 42:121–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donadeu FX, Ascoli M 2005 The differential effects of the gonadotropin receptors on aromatase expression in primary cultures of immature rat granulosa cells are highly dependent on the density of receptors expressed and the activation of the inositol phosphate cascade. Endocrinology 146:3907–3916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunzicker-Dunn M, Maizels ET 2006 FSH signaling pathways in immature granulosa cells that regulate target gene expression: branching out from protein kinase A. Cell Signal 18:1351–1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne CM, Fan HY, Cheng X, Richards JS 2007 FSH induces multiple signaling cascades: evidence that activation of SRC, RAS and the EGF receptor are critical for granulosa cell differentiation. Mol Endocrinol 21:1940–1957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stastny M, Cohen S 1972 The stimulation of ornithine decarboxylase activity in testes of the neonatal mouse. Biochim Biophys Acta 261:177–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Teerds K, Dorrington J 1992 Growth factor requirements for DNA synthesis by Leydig cells from the immature rat. Biol Reprod 46:335–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SA, Khan SJ, Dorrington JH 1992 Interleukin-1 stimulates deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis in immature rat Leydig cells in vitro. Endocrinology 131:1853–1857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgett JR 2005 Recent advances in the protein kinase B signaling pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol 17:150–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andric N, Ascoli M 2006 A delayed, gonadotropin-dependent and growth-factor mediated activation of the ERK1/2 cascade negatively regulates aromatase expression in granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol 20:3308–3320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andric N, Ascoli M 2008 Mutations of the lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor that do not activate the phosphoinositide cascade allow hCG to induce aromatase expression in immature rat granulosa cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 285:62–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andric N, Ascoli M 2008 The lutropin receptor activated ERK1/2 cascade stimulates epiregulin release from granulosa cells. Endocrinology 149:5549–5556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]