Abstract

GNAS gives rise to multiple imprinted gene products, including the α-subunit of the stimulatory G protein (Gsα) and its variant XLαs. Based on genomic sequence, the translation of XLαs begins from the middle of a long open reading frame, suggesting the existence of an N-terminally extended variant termed extralarge XLαs (XXLαs). Although XXLαs, like Gsα and XLαs, would be affected by most disease-causing GNAS mutations, its authenticity and biological significance remained unknown. Here we identified a mouse cDNA clone that comprises the entire open reading frame encoding XXLαs. Whereas XXLαs mRNA was readily detected in mouse heart by RT-PCR, it appeared virtually absent in insulinoma-derived INS-1 cells. By Northern blots and RT-PCR, XXLαs mRNA was detected primarily in the mouse brain, cerebellum, and spleen. Immunohistochemistry using a specific anti-XXLαs antibody demonstrated XXLαs protein in multiple brain areas, including dorsal hippocampus and cortex. In transfected cells, full-length human XXLαs was localized to the plasma membrane and mediated isoproterenol- and cholera toxin-stimulated cAMP accumulation. XXLαs-R844H, which bears a mutation analogous to that in the constitutively active Gsα mutant Gsα-R201H (gsp oncogene), displayed elevated basal signaling. However, unlike Gsα-R201H, which mostly remains in the cytoplasm, both XXLαs-R844H and a constitutively active XLαs mutant localized to the plasma membrane. Hence, XXLαs is a distinct GNAS product and can mimic Gsα, but the constitutively active XXLαs and Gsα mutants differ from each other regarding subcellular targeting. Our findings suggest that XXLαs deficiency or hyperactivity may contribute to the pathogenesis of diseases caused by GNAS mutations.

Representing a distinct product of the GNAS locus, XXLαs can mimic Gsα with respect to cAMP generation, but unlike the constitutively active form of the latter, constitutively active XXLαs is associated predominantly with the plasma membrane.

GNAS is a complex locus giving rise to multiple gene products. The most extensively investigated GNAS product is the α-subunit of the stimulatory G protein (Gsα), which is essential for the actions of multiple hormones and other agonists (1,2). Heterozygous GNAS mutations that impair Gsα activity and/or expression lead to various endocrine and skeletal diseases, including pseudohypoparathyroidism, Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy, and progressive osseous heteroplasia (POH). In addition, mutations causing constitutive Gsα activity (gsp oncogene) are found in a variety of endocrine tumors, such as GH-secreting adenomas, and some other neoplasia including juvenile ovarian granulosa cell tumor and clear cell renal carcinoma (1,2,3,4,5). Postzygotic, constitutively activating Gsα mutations are also found in patients with McCune-Albright syndrome (MAS), a disorder characterized by the clinical triad of hyperpigmented skin lesions (café-au-lait spots), pubertal precocity, and fibrous dysplasia of bone (1,2).

In addition to Gsα, which is encoded by exons 1–13 (6), GNAS gives rise to several gene products that show imprinted expression profiles (7,8,9,10,11). Among those is the extralarge α-subunit (XLαs), a paternally expressed protein that shares exons 2–13 with Gsα but uses a distinct upstream promoter and an alternative first exon (7,9,12). With the exception of its N-terminal portion, XLαs is identical with Gsα, comprising most of the functional domains shown to be important for Gsα activity. Accordingly, XLαs can mimic Gsα function in transfected cells (13,14,15). On the other hand, the phenotypes of XLαs and Gsα knockout mice differ markedly from each other (16,17,18,19), thus arguing against a role for XLαs that is identical with the role of Gsα in vivo. Based on the findings in the XLαs knockout mice, this protein is essential for postnatal adaptation to feeding and glucose and energy metabolism (16). In humans, large chromosomal deletions comprising the entire paternal GNAS allele (i.e. complete loss of XLαs combined with a loss of one copy of Gsα) results in perinatal phenotypes similar to those observed in XLαs knockout mice (20), suggesting that the cellular function of XLαs may be conserved between humans and mice. However, the significance of this protein still remains uncertain in humans because patients with pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism, who carry paternal inactivating GNAS mutations, are considered to have no specific features that differ from those observed in patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism-Ia,who carry maternal inactivating GNAS mutations (1,2).

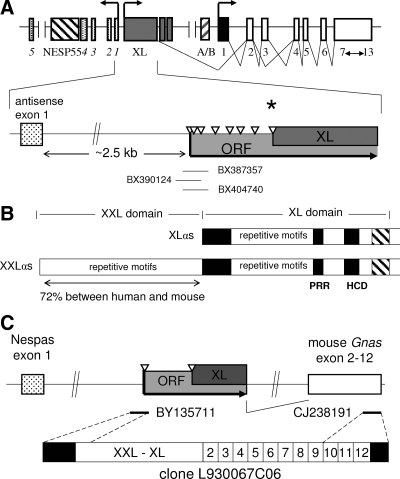

The translation initiation site of XLαs is presumed to be located in the middle of a long open reading frame (ORF) (12,21), the start of which resides about 2.5 kb upstream of GNAS antisense transcript exon 1 (10,11). This long ORF suggests the presence of an XLαs mRNA variant that extends in the 5′ direction, termed XXLαs (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, whereas both human (7) and rat XLαs (12) lack a typical Kozak sequence at the presumed translation initiation site, the first ATG of the ORF, i.e. the start of XXLαs, lies within a Kozak sequence in both humans and rodents. The predicted XXLαs protein thus comprises either 301 or 429 additional amino terminal residues relative to human and rat XLαs, respectively. The highly conserved regions in the XL domain of XLαs are limited to a proline-rich region, a highly charged domain, and a conserved stretch of about 60 amino acids at the N terminus (Fig. 1B). The sequence of the remaining portion is poorly conserved (although proline and alanine rich repeat motifs exist in both rodents and humans). In contrast, the sequence within the XXL domain, i.e. upstream to the presumed start of XLαs, is highly conserved, with 72% homology between humans and mice (Fig. 1B). These structural features suggest that XXLαs may be a real product of GNAS and that its XXL domain may confer certain functional properties. However, little evidence supports the existence of XXLαs. There are few nonspliced human and mouse expressed sequence tags (ESTs) that map to the upstream region of the ORF, and a single study amplified, by RT-PCR, a nonspliced portion of this region from mouse total brain RNA (22). It is unknown whether transcripts that comprise the entire ORF (thus predicted to encode XXLαs) really exist and whether XXLαs is a distinct GNAS product.

Figure 1.

cDNA identified in RIKEN mouse library supports the existence of full-length XXLαs. A, GNAS is a complex locus with multiple gene products. Based on ESTs, the translational start site of human XLαs (asterisk) is located at the eighth ATG (open triangles) of a long ORF. Thus, the in-frame amino acids N terminal to this start site can lead to an N-terminally extended XLαs variant, termed XXLαs. Horizontal lines depict human ESTs that map to this genomic region. Boxes and connecting lines depict exons and introns, respectively. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription. Splicing pattern is shown for major Gsα and XLαs transcripts only. The GNAS antisense transcript exons are stippled and numbered in italics. B, The XXL and the XL protein domains are depicted to indicate the structural features. Black shaded boxes mark the highly conserved regions. The hatched box indicates the C-terminal end of the XL domain homologous to the exon 1 encoded portion of Gsα. PRR, Proline-rich region; HCD, highly charged domain. C, Clone L930067C06, which gave rise to ESTs BY135711 and CJ238191, was identified from a 17.5 d postcoitum whole-embryo library. This clone comprises cDNA that encodes the full-length mouse XXLαs protein including the alternatively spliced GNAS exon 3. Nespas is the mouse ortholog of the GNAS antisense transcript.

Based on its definition, XXLαs would be completely inclusive of XLαs, and therefore, XXLαs activity and/or expression is predicted to be altered in all in vivo XLαs knockout models (16,23,24) and in most diseases caused by mutations within GNAS (1,2). Thus, XXLαs is a potentially important GNAS product that may be involved in physiology and disease pathogenesis. However, the cellular functions of XXLαs are entirely unknown. In the present study, we examined the expression of XXLαs in different tissues and addressed whether it can have a signaling function similar to Gsα and XLαs. Our findings revealed that XXLαs is a genuine GNAS product, which can be expressed differently from XLαs. We further showed that XXLαs is a plasma membrane protein with an ability to mediate adenylyl cyclase stimulation. We also demonstrated that a constitutively active XXLαs mutant, unlike the cognate Gsα mutant, remains associated with the plasma membrane.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Rat insulinoma-derived INS-1 cells were a kind gift of Professor Claes B. Wollheim (University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland) (25). GnasE2−/E2− cells, which are mouse embryonic fibroblasts homozygous for the disruption of exon 2 and, thus, null for Gsα, XLαs, and XXLαs, have been described (15). Tissues for RNA and protein analysis were isolated from mice at different ages. The procedures for these studies were done in compliance with the International Animal Care and Use Convention and approved by Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) subcommittee on research animal care.

RNA studies

Northern blot

Total RNA was extracted by using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Polyadenylated (polyA+) RNA was isolated from total RNA by using the Oligotex mRNA kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). Either 15 μg total RNA or 10 μg polyA+ RNA were separated on 1.3% formaldehyde agarose gel and subsequently blotted on supported nitrocellulose (Osmonics Inc., Minnetonka, MN) or ZetaProbe GT nylon (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The XXLαs hybridization probe was amplified by PCR from mouse genomic DNA, spanning nucleotides 78–1074 with respect to the ORF. The probe for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was amplified by RT-PCR using mouse heart total RNA and the following forward and reverse primers, respectively: 5′-CGTCCCGTAGACAAAATGGT-3′ and 5′-TGTGAGGGAGATGCTCAGTG-3′. The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) was used to verify that each probe was highly specific for its target transcript. The probes were verified by direct sequence analysis (MGH DNA Core Facility). Probes were labeled with random primed labeling using 32P-dCTP. Hybridizations were carried out at 42 C with a buffer containing 50% formamide as described (26) or the UltraHyb hybridization solution (Ambion, Austin, TX). Blots were washed with 0.1× standard saline citrate/0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at either 60 or 42 C. Autoradiography was performed to detect hybridizing transcripts.

5′-Rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE)

The GeneRacer kit (Invitrogen) was used in 5′-RACE experiments according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, total RNA was first treated with calf intestinal phosphatase and, subsequently with tobacco acid pyrophosphatase. An RNA oligo, which was provided with the kit, was then ligated to the treated RNA by using T4 RNA ligase. The ligation product was reverse transcribed by either random primers or gene-specific primers (position −335 and +413 relative to first ATG). The reverse transcription (RT) mixture was subjected to nested PCR using forward primers specific to the ligated RNA oligo and reverse primers specific to XXLαs. Amplicons were gel purified and subcloned into pCR4-TOPO (Invitrogen), followed by nucleotide sequence analysis (MGH DNA Core Facility).

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from various tissues of 2-month-old mice. After treatment with deoxyribonuclease I (Invitrogen), 1 μg total RNA was reverse transcribed by using the first strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen) and random hexamer primers. Real-time PCR was performed by using the SYBR green Quantitech kit (QIAGEN). For amplification of XXLαs mRNA, the forward primer was 5′-CGAGCAAGAACCTTTGGAAG-3′ (primer a), and the reverse primer was 5′-TGATCTCACTGCCAGTCTCG-3′ (primer b). For amplification of both XXLαs and XLαs mRNA, the forward primer was 5′-CTCATCGACAAGCAACTGGA-3′ (primer c), and the reverse primer was 5′-CCCTCTCCGTTAAACCCATT-3′ (primer d). For amplification of succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit A (Sdha) mRNA, the forward primer was 5′-AAGGCAAATGCTGGAGAAGA-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-ATACACTCCCCACACGGAAC-3′. The amplification efficiency of each PCR product was about 2. Data were analyzed as previously described (27) by using the Q-Gene module (28).

cDNA constructs and transfections

cDNA encoding human XXLαs was constructed by PCR amplification of the fragment encoding the XXL domain from genomic DNA and subsequent ligation of the product to the 5′ end of human XLαs cDNA, which had been subcloned into pcDNA3.1_hygro(−), as described (14). Each construct had an hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag inserted within the portion encoded by the alternatively spliced exon 3. Point mutations and the N-terminal FLAG epitope were introduced by using standard methods. cDNA encoding mouse XXLαs was obtained from RIKEN mouse FANTOM cDNA library and then subcloned into pcDNA3.1_hygro(−). Transfections were performed by using either Effectene (QIAGEN) for GnasE2−/E2− cells or Fugene (Roche, Stockholm, Sweden) for HEK293 cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Generation of polyclonal anti-XXLαs antiserum

Rabbit polyclonal antiserum that immunoreacts with both human and mouse XXLαs was raised against the peptide SQPPLQVPDLAPGGPEA, which had been synthesized and coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin via a terminally added cysteine at the MGH Biopolymer Core Facility. Injections and serum collections were carried out by Cocalico Biologicals Inc. (Reamstown, PA). The effectiveness of the antiserum was tested by Western blot using membrane lysates of HEK293 cells transfected with empty vector or cDNA encoding either mouse or human XXLαs. Proteins were separated by 9% SDS-PAGE. After transfer, the blot was incubated with the antiserum (1:2000) and then peroxidase-conjugated antirabbit IgG. Immunoreactivity was detected by chemiluminescence (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Waltham, MA).

Tissue collection, preparation, and immunohistochemistry

Paraffin tissue processing

Immediately after a 16-month-old mouse was euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, the brain was removed. The right hemibrain was cut into three coronal sections, 2 mm in thickness, using a coronal matrix, as described (29). The three coronal sections, which spanned from 3 mm anterior to the bregma to 3 mm posterior to the bregma, were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 2 h and embedded in a single paraffin block. The paraffin-blocks were cut serially in 10-μm sections; each section consisted of three anterior-posterior coronal levels and each block encompassed the entire mid section of the hemibrain. Sections were immunostained by using either the anti-XXLαs antiserum or preimmune rabbit serum (1:5000 dilution).

Sections for immunostaining were processed using the Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). After the appropriate biotinylated secondary antibody, slides were developed with diaminobenzidine for the exact same amount of time and counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted.

Frozen tissue processing

After removal and overnight fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, the brain was dissected and cryoprotected in 10% and then 20% glycerol in dimethylsulfoxide/PBS. Coronal sections were obtained on a freezing microtome at 60 μm and stored in phosphate buffer with 0.01% sodium azide at 4 C.

Free-floating sections were subsequently incubated overnight with the anti-XXLαs antiserum or the preimmune serum (1:10,000 dilution) in primary diluent (0.3% Triton X-100, 0.01% sodium azide, and 2% goat serum in PBS) followed by PBS washes and incubation in peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and developed using diaminobenzidine as a chromagen.

Subcellular localization

For determining the localization of XXLαs alone, HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding native XXLαs, XXLαs-M302V, or N terminally FLAG-tagged XXLαs. For comparing the localizations of native and constitutively active forms of XXLαs, Gsα, and XLαs, HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding these proteins in addition to plasmids encoding Gβ1 and Gγ2. Cells were analyzed 72 h after transfection by confocal indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, cells were incubated with rabbit anti-HA (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA) or mouse anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma). Immunoreactivity was detected after incubation with Cy3-conjugated antirabbit IgG or Alexa Fluor488-conjugated antimouse IgG. Laser confocal microscopy was performed at × 75 magnification, as described previously (14). For Western blot analysis, particulate and soluble fractions of cell lysates were prepared as described previously (30). Upon separation of proteins by either 10% (Gsα) or 6% (for XLαs and XXLαs) SDS-PAGE, Western blot was performed by using either rabbit anti-HA antibody (AbCam, Cambridge, MA) or a rabbit antibody against the C terminus common to Gsα, XLαs, and XXLαs (Upstate Biologicals, Lake Placid, NY). Proteins were visualized by goat antirabbit secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and a chemiluminescence detection system (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

cAMP measurements

cAMP accumulation was determined 72 h after transfection of GnasE2−/E2− cells. Cholera toxin (CTX) treatment was performed for 4 h, after which the cells were incubated 15 min in a buffer containing 2 mm isobutyl methylxanthine at 37 C. Basal and agonist (10 μm isoproterenol)-stimulated cAMP levels were after incubation in the presence of 2 mm isobutyl methylxanthine for 15 min at 37 C. After stimulation, the medium was removed and cells were lysed with 50 mm HCl. RIA was performed to determine the amount of cAMP, as described (31).

Results

A mouse cDNA clone is predicted to encode full-length XXLαs

Despite the potential biological importance of XXLαs, the existence of this GNAS product is supported by little evidence. To determine whether a full-length XXLαs transcript really exists, we searched the databases for ESTs derived from cDNA clones that comprise the entire ORF (i.e. predicted to encode full length XXLαs). In the mouse, we identified ESTs BY135711 and CJ238191, which were derived from the 5′- or 3′-end sequences of clone L930067C06 and aligned to the genomic region immediately upstream of the first ATG of the ORF and to the terminal Gnas exon (exon 12 in mouse), respectively. We acquired this RIKEN mouse FANTOM cDNA clone, which was derived from 17.5 d postcoitum whole embryo (32). Sequence analysis of this clone revealed a 4015-bp insert comprising the entire XXLαs ORF (Fig. 1C); the sequence included exon 3, which is known to be alternatively spliced in Gsα and other transcripts derived from this locus. The 5′ end of the insert was 257 bp upstream of the first ATG for XXLαs.

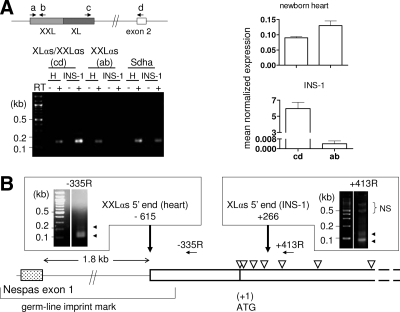

XXLαs and XLαs are expressed differentially in newborn heart and pancreatic INS-1 cells, respectively

An undefined transcript larger than XLαs has previously been detected by an XLαs-specific probe in Northern blots, and this transcript was abundant in heart from 4-d-old mice (16). Because this large transcript could conceivably reflect XXLαs, we tried amplifying XXLαs mRNA from this tissue by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. The amount of mRNA relative to Sdha mRNA (used as control) appeared comparable regardless of whether the amplification primers were specific only to XXLαs (primers a and b) or both XXLαs and XLαs (primers c and d) (Fig. 2A). In contrast, when we used total RNA isolated from INS-1 cells, a cell line of rat pancreatic β-cell origin (25), primers specific to both XXLαs and XLαs (primers c and d) showed markedly higher mRNA levels (>1000-fold) than primers specific only to XXLαs (primers a and b) (Fig. 2A). These findings thus indicated that, whereas newborn heart expresses predominantly XXLαs, INS-1 cells express predominantly XLαs.

Figure 2.

XXLαs transcript is expressed differently from XLαs transcript. A, Left, Amplification of XXLαs and XLαs transcripts by RT-PCR. Primers (arrows) used for quantitative real-time RT-PCR to amplify XXLαs alone (a and b) or XXLαs and XLαs together (c and d) from either newborn mouse heart (H) or INS-1 cells, an insulinoma-derived cell line, are shown above the schematic of the relevant GNAS exons (boxes). Representative ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel shows RT-PCR amplicons generated by using primers a and b or primers c and d. Sdha transcript was amplified as control. Right, Expression of XXLαs and XLαs mRNA normalized to Sdha mRNA. Data are mean ± sem of three or more independent experiments. B, The origin of XXLαs and XLαs transcription. The most 5′ location (vertical arrows) in either newborn mouse heart or INS-1 cells was determined by 5′-RACE. The gene-specific primers used for RT are indicated by horizontal arrows; ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels show the amplicons (arrowheads) that were cloned and sequenced. Open triangles depict the approximate locations of the ATG triplets in the XXLαs ORF. Nespas exon and the germline imprint mark are indicated. NS, Non-specific.

The 5′-untranslated region of XXLαs mRNA extends into a germ-line imprint mark in newborn mouse heart

Both the Nespas promoter and XL exon reside in a single differentially methylated region (10,11,33), but only the portion of this region that comprises the Nespas promoter constitutes a germ-line imprint mark, i.e. methylated in the oocyte but not sperm (34) (Fig. 2B). The first ATG of the XXLαs ORF in the mouse is located 389 bp downstream from the apparent telomeric boundary of this imprint mark (34). To determine whether the 5′-untranslated region of XXLαs mRNA extends into this region, we performed 5′-RACE using total RNA from newborn mouse heart and various reverse primers located upstream or downstream of XXLαs ATG. The RT was performed by random primers but the forward primer was specific to the RNA oligo ligated to the 5′ end before RT, thereby providing amplification of the sense transcript only. We also repeated 5′-RACE, using a gene-specific primer for RT (position −335 relative to ATG) (Fig. 2B). Cloning and subsequent sequencing of the 5′-RACE products showed that the 5′-untranslated region of XXLαs mRNA varies between 513 and 615 nucleotides in newborn heart, indicating that the XXLαs transcript originates from within the germ-line imprint mark (Fig. 2B). According to these results, the start of the XXLαs transcript and Nespas exon 1 were ∼1.8 kb apart. We also performed 5′-RACE, using total RNA extracted from INS-1 cells, but the same gene-specific and reverse amplification primers used for amplifying the 5′ end of XXLαs transcript in newborn heart did not lead to any specific amplicons. On the other hand, primers located within the ORF, i.e. downstream of the first ATG, resulted in specific amplification products when 5′-RACE was performed on INS-1 total RNA. Based on experiments using RT derived from random primers or a gene-specific primer (position +413 relative to ATG), the longest transcript originated from 266 bp downstream of the first ATG, thus excluding the first four translation initiation sites of the ORF (Fig. 2B).

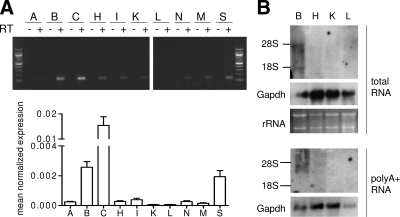

XXLαs mRNA is expressed in various newborn and adult mouse tissues

To determine the tissue distribution of XXLαs mRNA, we examined XXLαs transcript expression in various adult mouse tissues. RT-PCR and real-time quantitative RT-PCR analyses demonstrated that the XXLαs transcript is abundant in cerebellum, followed by brain and spleen, although expression could be detected in multiple other tissues (Fig. 3A). We next performed Northern blot analysis with a probe specific to XXLαs and were able to detect a hybridization signal when we used RNA isolated from newborn mouse tissues. A hybridizing band slightly shorter than 28S rRNA (4.7 kb) was prominent in the brain, whereas no specific hybridization signal was detectable in heart, kidney, and liver (Fig. 3B). A shorter transcript was also observed in total brain RNA, but it appeared markedly lower in abundance than the large transcript (Fig. 3B). We repeated the Northern blots with polyA+ RNA from newborn mouse tissues and confirmed the presence of XXLαs transcript in the brain (Fig. 3B). This analysis also revealed a hybridizing transcript in heart, which appeared to be significantly less abundant than in brain (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Tissue distribution of XXLαs mRNA. Panel A, Top, RT-PCR analysis for examining the expression of XXLαs mRNA in various adult mouse tissues including white adipose tissue (A), brain (B), cerebellum (C), heart (H), small intestine (I), kidney (K), liver (L), lung (N), skeletal muscle (M), and spleen (S). Bottom, Real-time RT-PCR using Sdha mRNA as a reference control was used to assess relative expression. Data are mean ± sem of triple measurements. Results are representative of two experiments with similar results. Panel B, Northern blot analysis of XXLαs transcript by using 15 μg per lane total RNA or 10 μg polyA+ RNA isolated from newborn mouse whole brain (B), heart (H), kidney (K), and liver (L). The locations of 28S and 18S rRNA are indicated. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) probe was used as control.

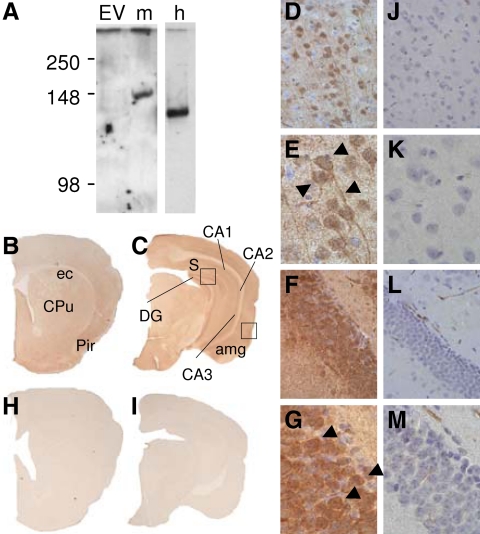

Specific immunostaining for XXLαs is detected in mouse dorsal hippocampus and brain cortex

To detect the XXLαs protein, we developed a rabbit polyclonal antiserum targeted to an epitope within the XXL domain of mouse XXLαs. Western blots using the anti-XXLαs antiserum detected both mouse and human XXLαs in lysates of HEK293 cells transiently transfected with cDNA encoding either of these proteins (Fig. 4A), consistent with the high homology between the mouse and human XXL domains; the homology is particularly high within the epitope used to raise the antiserum, with 14 of 17 residues being identical. In contrast, no immunoreactive bands were detectable in lysates of HEK293 cells transfected with the empty vector (Fig. 4A). Similar to the previous findings with rat and human XLαs (35), the electrophoretic mobility of XXLαs appeared slower than its predicted molecular mass (122 and 110 kDa for mouse and human XXLαs, respectively). On immunohistological analysis of coronal brain sections from mice, there was no immunoreactivity for the preimmune serum in any of the anterioposterior levels (Fig. 4, H–M), whereas clear immunoreactivity was observed for the anti-XXLαs antiserum in dorsal hippocampus, in subiculum, CA1, dentate gyrus subfields extending into the CA3 subfield as well as diffuse dendritic staining in the hippocampus and cortical subfields (Fig. 4, B–G). Sections of the cortex showed intense, specific immunostaining with the anti-XXLαs antiserum, demonstrating, in some neuronal bodies, peripheral staining suggesting plasma membrane localization (Fig. 4, B–G).

Figure 4.

Anti-XXLαs antiserum detects expression of this protein in specific areas of mouse brain. A, Rabbit polyclonal antiserum raised against an epitope within the XXL domain of mouse XXLαs was characterized by Western blot using lysates of HEK293 cells transiently transfected with empty vector (EV), mouse XXLαs (m), or human XXLαs (h). Equal volumes of lysates derived from confluent cells grown in six-well dishes were loaded in each lane. Signal intensity from human XXLαs-transfected cells was markedly higher than that from mouse XXLαs-transfected cells, and therefore, an image obtained with lower exposure time is shown for human XXLαs. B–M, Coronal sections of wild-type mouse brain were immunostained with anti-XXLαs antiserum (B–G) or preimmune rabbit serum (H–M) at two levels anterior (B and H) and posterior (C and I) to bregma. Dorsal hippocampus dentate gyrus (DG) shows intense staining for XXLαs in subiculum (S), CA1, CA2, and CA3 subfields. Sections of secondary somatosensory cortex show intensely stained neurons interspersed with lightly stained neurons; staining extends into the apical dendrites (D, original magnification, ×400; E, original magnification, ×1000). Hippocampus shows intensely stained neurons as well as diffuse dendritic staining (F, original magnification, ×400; G, original magnification, ×1000). No positive staining was observed in any of the regions studied with the preimmune serum (H–M). Squares indicate the areas in which images with higher magnification are presented in panels D–G and J–M. Arrows indicate examples of structures showing specific staining. CPu, Caudate putamen (striatum); Pir, piriform cortex; ec, external capsule; amg, amygdala.

XXLαs is localized to the plasma membrane in transfected cells

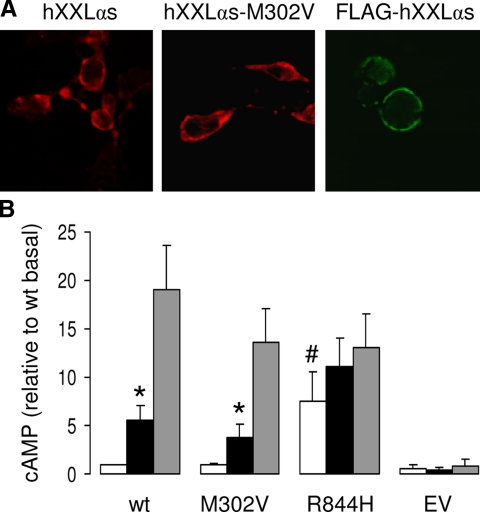

To investigate the functional properties of XXLαs protein, we engineered cDNA encoding human XXLαs with an HA-epitope tag located within the portion encoded by the alternatively spliced exon 3. This HA tag has been previously inserted into the Gsα and XLαs backbones (14,36,37) and is not predicted to alter activity regarding basal and receptor-activated adenylyl cyclase stimulation. To determine the subcellular localization of XXLαs, we transfected HEK293 cells with XXLαs cDNA and performed confocal indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. In cells transiently expressing XXLαs, anti-HA antibody detected specific immunostaining at the plasma membrane (Fig. 5A); there was no immunostaining in cells transfected with empty vector (data not shown). To ensure that the observed immunostaining resulted from the expression of XXLαs and not from the expression of XLαs, we generated a mutant XXLαs in which a valine residue was substituted for the methionine corresponding to the initiator of XLαs (XLαs-M302V). We also generated an XXLαs variant tagged with a FLAG epitope in its N terminus. In cells transiently expressing either of these variants, immunostaining was also localized to the plasma membrane (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

XXLαs localizes to the plasma membrane and can mediate cAMP accumulation in response to CTX or isoproterenol. A, HEK293 cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding wild-type human XXLαs (hXXLαs), a mutant XXLαs in which the methionine residue corresponding to the initiator of XLαs was changed to a valine (M302V), or an N terminally FLAG-tagged XXLαs. Cells were fixed and analyzed 3 d later by indirect confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. Wild-type and the M302V mutant carried an HA tag, which was used for immunodetection. B, Intracellular cAMP accumulation was measured in GnasE2−/E2− cells transfected with a plasmid encoding wild-type human XXLαs (wt), a mutant XXLαs in which the methionine residue corresponding to the initiator of XLαs was changed to a valine (M302V), a mutant XXLαs analogous to the constitutively active Gsα mutant R201H (R844H), or with empty vector (EV). Data represent mean ± sem of four independent experiments after each experiment was normalized to the basal cAMP value obtained in XXLαs expressing cells (3.1 ± 0.9 pmol/well). *, P < 0.05 compared with basal; #, P < 0.05 compared with the basal in wt XXLαs expressing cells according to Student’s t test.

XXLαs can mimic Gsα in mediating stimulation of cAMP generation

To determine whether XXLαs, like XLαs and Gsα, can mediate cAMP formation, we transfected GnasE2−/E2− cells (mouse embryonic fibroblasts null for XLαs, Gsα, and XXLαs) with cDNA encoding XXLαs. Isoproterenol (agonist for the endogenous β-adrenergic receptor) or CTX stimulation of cells transiently expressing XXLαs resulted in a 5.6 ± 1.5- and 19 ± 4.5-fold increase in intracellular cAMP accumulation, respectively (Fig. 5B). Cells transiently expressing XXLαs-M302V also exhibited a robust cAMP response to isoproterenol or CTX stimulation (4.7 ± 1.9- and 14.9 ± 3.3-fold, respectively). In cells transiently expressing XXLαs-R844H, which is analogous to the constitutively active Gsα-R201H mutant (38,39), the basal cAMP levels peaked 7.6 ± 2.9-fold higher than in cells transiently expressing native XXLαs (Fig. 5B).

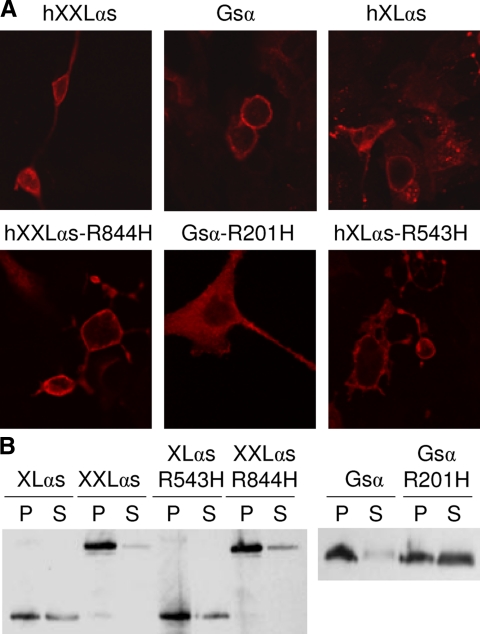

Constitutive activation of Gsα, but not XXLαs or XLαs, results in localization to cytoplasm

GNAS mutations that cause constitutive cyclase stimulation, such as those found in various endocrine and nonendocrine tumors (3) and in patients with MAS (38) result in the localization of Gsα primarily in the cytoplasm (36). Because these mutations are located in exons 8 or 9 and thus affect XXLαs, we asked whether their effect on XXLαs regarding subcellular trafficking is the same as their effect on Gsα. Surprisingly, the constitutively active XXLαs-R844H mutant, like native XXLαs, localized to the plasma membrane in transfected HEK293 cells (Fig. 6A). This was in contrast to the cognate Gsα mutant Gsα-R201H, which, unlike native Gsα, localized primarily to the cytoplasm (Fig. 6A). We then addressed whether XLαs would also remain in the membrane despite constitutive activation. Immunostaining for both native XLαs and XLαs-R543H, which is also analogous to Gsα-R201H and mediates constitutive cAMP signaling (data not shown), was detected at the plasma membrane (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, Western blot analysis showed that both wild-type and constitutively active forms of XXLαs and XLαs were present more abundantly in the particulate fraction than the soluble fraction of transiently transfected HEK293 cell lysates (Fig. 6B). In contrast, most Gsα-R201H immunoreactivity was present in the soluble fraction, whereas wild-type Gsα was predominantly in the particulate fraction (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Constitutively active XXLαs remains associated with the plasma membrane. A, Confocal immunofluorescence analysis of HEK293 cells transiently expressing wild-type or constitutively active forms of Gsα, XLαs, and XXLαs. Fixed and permeabilized cells were incubated with a polyclonal anti-HA antibody. B, Western blot analysis of transfected HEK293 cells. Relative abundance of each wild-type and constitutively active protein was determined in the particulate (P) and the soluble (S) fractions, as indicated. Equal volumes of particulate and soluble fractions were loaded on the gel. Anti-HA antibody was used to detect the transiently expressed Gsα and Gsα-R201H, whereas an antibody against the common C terminus of all these proteins was used to detect the transiently expressed XLαs, XXLαs, XLαs-R543H, and XXLαs-R844H.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that XXLαs is a distinct GNAS product and that it is capable of mediating cAMP signaling. We also revealed differences between the subcellular localizations of constitutively active XXLαs, XLαs, and Gsα mutants.

Consistent with previous data showing expression of XLαs in the pancreas (16,21), we determined that INS-1 cells express XLαs. In fact, XLαs rather than XXLαs is found in these cells. These findings indicate that transcripts encoding these two GNAS products can be expressed in a tissue-specific manner. Our results show that XXLαs transcript is expressed predominantly in brain, cerebellum, and spleen, although lower levels were also detectable in other tissues. Consistent with the predominant expression of XXLαs in brain, the RT-PCR that amplified a nonspliced portion of XXLαs transcript was performed on RNA isolated from whole brain (22). Also, the ESTs that map specifically to XXLαs are derived from cells or tissues of neuronal origin, such as the NT2 neuroprogenitor cell line and neuroblastoma. Our immunohistochemical analysis revealed XXLαs protein in distinct regions of the mouse brain, particularly in the dorsal hippocampus and the cortex. The functional role of XXLαs in the central nervous system remains to be determined. Similar to XXLαs, significant XLαs expression has been documented in cerebellum (12,21), indicating that both GNAS products are coexpressed in this tissue. In situ hybridization experiments has demonstrated XLαs expression in other brain regions, particularly in pons and medulla oblongata (16), and it remains to be determined whether XXLαs is also expressed at these sites.

The genomic region encompassing GNAS antisense exon 1 and exon XL exhibits complex epigenetic features (7,10,34,40). Based on our findings, XXLαs mRNA extends into a germline-specific imprint mark (34), suggesting that the XXLαs transcript could have roles in the regulation of imprinting at the GNAS locus. Consistent with this prediction, it has recently been shown that the CCCTC binding factor, an insulator binding protein critical for regulation of imprinting (41,42), binds to the region immediately upstream of the ORF encoding human XXLαs (43). However, disruption of XXLαs (together with XLαs) is not associated with any changes in Gnas imprinting (16), thus refuting the possibility that XXLαs protein or its transcript plays a role in the imprinting of this locus.

Functionally, XXLαs appears to be able to mimic Gsα. It can mediate basal as well as agonist- and CTX-stimulated accumulation of cAMP. Consistent with this signaling activity, XXLαs is localized to the plasma membrane. However, we detected clear differences between the constitutively active forms of XXLαs and Gsα with respect to subcellular localization. Interaction with Gβγ is critical for membrane targeting of native Gsα (44), and activation of the latter, induced by receptor activation, CTX treatment, or mutations that inhibit the intrinsic GTPase activity, results in a loss of membrane avidity (30,36,45). Because constitutively active XXLαs and XLαs mutants, unlike constitutively active Gsα mutants, are targeted to the plasma membrane, XXLαs and XLαs may differ from Gsα with respect to the mechanisms governing membrane targeting. Further studies are needed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the subcellular targeting of these proteins.

Our finding that constitutively active XXLαs can cause elevated basal cAMP accumulation and that it mostly localizes, unlike the cognate Gsα mutant, to the plasma membrane may have important implications in disease pathogenesis. Because the maternal XXLαs promoter lies within a methylated region and is thus predicted to be silenced, this is particularly true regarding mutations located on the paternal GNAS allele. In GH-secreting somatotroph adenomas and in MAS patients with acromegaly, the constitutively activating GNAS mutations are predominantly on the maternal allele (46,47). On the other hand, paternal constitutively activating mutations have been found in other hyperfunctioning adenomas and in some MAS patients without acromegaly (47). Sustained signaling from XXLαs in the latter cases may thus contribute to the molecular pathology. In wild-type and fibrous dysplastic stromal cells from patients with fibrous dysplasia, who are mosaic for the same GNAS mutations, XLαs has been shown to be biallelic, but this was done through the use of primers common to XXLαs and XLαs (48). Thus, constitutively active forms of XXLαs may play roles in the pathogenesis of fibrous dysplasia regardless of the parental origin, although this possibility needs to be revisited upon more rigorous determination of allelic XLαs/XXLαs expression in stromal cells.

Ablation of XLαs in mice results in multiple postnatal defects including a failure in postnatal adaptation to feeding, postnatal growth retardation, and abnormalities in glucose and energy metabolism (16,19,23,24,49). Two unrelated children with large paternal GNAS deletions have also been reported to have early postnatal defects that are similar to those observed in XLαs knockout mice (20). Importantly, both XLαs and XXLαs are disrupted in all of the available in vivo mouse models and the children with the paternal GNAS deletions. XXLαs deficiency may thus be involved in the molecular events that lead to the XLαs knockout phenotype. Likewise, impaired expression and/or activity of XXLαs may account for the clinical phenotypes of patients carrying inactivating mutations within the paternal GNAS allele with the exception of mutations in exon 1. POH, a disorder of severe ectopic bone formation (50), is associated with paternally inherited, inactivating GNAS mutations, and no isolated POH case with a mutation in exon 1 (which is not used by XXLαs or XLαs) has thus far been described (51,52,53,54). Thus, XXLαs and/or XLαs deficiency could contribute to the pathogenesis of POH, and this possibility remains to be investigated. Of note, however, severe ossifications similar to those seen in POH can be found in patients who carry maternal inactivating GNAS mutations (55,56), indicating that additional factors, such as genetic background and modifier loci, are also involved.

In summary, XXLαs is a bona fide GNAS product that is distinct from XLαs. Like Gsα and XLαs, XXLαs is localized to the plasma membrane and is able to mediate adenylyl cyclase stimulation. However, whereas constitutively active XXLαs behaves similarly to constitutively active XLαs, it differs dramatically from constitutively active Gsα regarding subcellular localization. Although the unique cellular functions of XXLαs (and XLαs) are currently unknown, deficiency or constitutive activation of XXLαs may contribute to the pathogenesis of human diseases caused by GNAS mutations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Harald Jüppner and Gino V. Segre for helpful discussions and Carol A. Kubilus for technical assistance in tissue processing and immunohistochemistry.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01DK073911 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (to M.B.); Alzheimer’s Disease Center Grant P30 AG13846 (to N.W.K.); and the Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Award (to A.D.). C.A. received a research fellowship award from the Gülhane Military Medical Academy, Turkish General Staff, Ankara, Turkey.

Current affiliation for H.A.W.T.: Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Lipids, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online May 7, 2009

Abbreviations: CTX, Cholera toxin; EST, expressed sequence tag; Gsα, α-subunit of the stimulatory G protein; HA, hemagglutinin; MAS, McCune-Albright syndrome; MGH, Massachusetts General Hospital; ORF, open reading frame; POH, progressive osseous heteroplasia; polyA+, polyadenylated; RACE, rapid amplification of cDNA ends; RT, reverse transcription; Sdha, succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit A; XLαs, extralarge Gsα; XXLαs, extralarge XLαs.

References

- Weinstein LS, Liu J, Sakamoto A, Xie T, Chen M 2004 Minireview: GNAS: normal and abnormal functions. Endocrinology 145:5459–5464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel AM, Weinstein LS 2004 Inherited diseases involving G proteins and G protein-coupled receptors. Annu Rev Med 55:27–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis CA, Masters SB, Spada A, Pace AM, Bourne HR, Vallar L 1989 GTPase inhibiting mutations activate the α chain of Gs and stimulate adenylyl cyclase in human pituitary tumours. Nature 340:692–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalfa N, Ecochard A, Patte C, Duvillard P, Audran F, Pienkowski C, Thibaud E, Brauner R, Lecointre C, Plantaz D, Guedj AM, Paris F, Baldet P, Lumbroso S, Sultan C 2006 Activating mutations of the stimulatory g protein in juvenile ovarian granulosa cell tumors: a new prognostic factor? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:1842–1847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalfa N, Lumbroso S, Boulle N, Guiter J, Soustelle L, Costa P, Chapuis H, Baldet P, Sultan C 2006 Activating mutations of Gsα in kidney cancer. J Urol 176:891–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozasa T, Itoh H, Tsukamoto T, Kaziro Y 1988 Isolation and characterization of the human Gsα gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:2081–2085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward BE, Kamiya M, Strain L, Moran V, Campbell R, Hayashizaki Y, Bronthon DT 1998 The human GNAS1 gene is imprinted and encodes distinct paternally and biallelically expressed G proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:10038–10043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward BE, Moran V, Strain L, Bonthron DT 1998 Bidirectional imprinting of a single gene: GNAS1 encodes maternally, paternally, and biallelically derived proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:15475–15480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, Wroe SF, Wells CA, Miller HJ, Bodle D, Beechey CV, Williamson CM, Kelsey G 1999 A cluster of oppositely imprinted transcripts at the Gnas locus in the distal imprinting region of mouse chromosome 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:3830–3835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward BE, Bonthron DT 2000 An imprinted antisense transcript at the human GNAS1 locus. Hum Mol Genet 9:835–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroe SF, Kelsey G, Skinner JA, Bodle D, Ball ST, Beechey CV, Peters J, Williamson CM 2000 An imprinted transcript, antisense to Nesp, adds complexity to the cluster of imprinted genes at the mouse Gnas locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:3342–3346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlenbach RH, Matthey J, Huttner WB 1994 XLαs is a new type of G protein. Nature [Erratum (1995) 375:253] 372:804–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemke M, Pasolli HA, Kehlenbach RH, Offermanns S, Schultz G, Huttner WB 2000 Characterization of the extra-large G protein α-subunit XLαs. II. Signal transduction properties. J Biol Chem 275:33633–33640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linglart A, Mahon MJ, Kerachian MA, Berlach DM, Hendy GN, Jüppner H, Bastepe M 2006 Coding GNAS mutations leading to hormone resistance impair in vitro agonist- and cholera toxin-induced adenosine cyclic 3′,5′-monophosphate formation mediated by human XLαs. Endocrinology 147:2253–2262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastepe M, Gunes Y, Perez-Villamil B, Hunzelman J, Weinstein LS, Jüppner H 2002 Receptor-mediated adenylyl cyclase activation through XLαs, the extra-large variant of the stimulatory G protein α-subunit. Mol Endocrinol 16:1912–1919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plagge A, Gordon E, Dean W, Boiani R, Cinti S, Peters J, Kelsey G 2004 The imprinted signaling protein XLαs is required for postnatal adaptation to feeding. Nat Genet 36:818–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Gavrilova O, Liu J, Xie T, Deng C, Nguyen AT, Nackers LM, Lorenzo J, Shen L, Weinstein LS 2005 Alternative Gnas gene products have opposite effects on glucose and lipid metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:7386–7391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain-Lee EL, Schwindinger W, Crane JL, Zewdu R, Zweifel LS, Wand G, Huso DL, Saji M, Ringel MD, Levine MA 2005 A mouse model of Albright hereditary osteodystrophy generated by targeted disruption of exon 1 of the Gnas gene. Endocrinology 146:4697–4709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie T, Plagge A, Gavrilova O, Pack S, Jou W, Lai EW, Frontera M, Kelsey G, Weinstein LS 2006 The alternative stimulatory G protein α-subunit XLαs is a critical regulator of energy and glucose metabolism and sympathetic nerve activity in adult mice. J Biol Chem 281:18989–18999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geneviève D, Sanlaville D, Faivre L, Kottler ML, Jambou M, Gosset P, Boustani-Samara D, Pinto G, Ozilou C, Abeguilé G, Munnich A, Romana S, Raoul O, Cormier-Daire V, Vekemans M 2005 Paternal deletion of the GNAS imprinted locus (including Gnasxl) in two girls presenting with severe pre- and post-natal growth retardation and intractable feeding difficulties. Eur J Hum Genet 13:1033–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasolli HA, Klemke M, Kehlenbach RH, Wang Y, Huttner WB 2000 Characterization of the extra-large G protein α-subunit XLαs. I. Tissue distribution and subcellular localization. J Biol Chem 275:33622–33632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramowitz J, Grenet D, Birnbaumer M, Torres HN, Birnbaumer L 2004 XLαs, the extra-long form of the α-subunit of the Gs G protein, is significantly longer than suspected, and so is its companion Alex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:8366–8371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Yu D, Lee E, Eckhaus M, Lee R, Corria Z, Accili D, Westphal H, Weinstein LS 1998 Variable and tissue-specific hormone resistance in heterotrimeric Gs protein α-subunit (Gsα) knockout mice is due to tissue-specific imprinting of the Gsα gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:8715–8720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner JA, Cattanach BM, Peters J 2002 The imprinted oedematous-small mutation on mouse chromosome 2 identifies new roles for Gnas and Gnasxl in development. Genomics 80:373–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asfari M, Janjic D, Meda P, Li G, Halban PA, Wollheim CB 1992 Establishment of 2-mercaptoethanol-dependent differentiated insulin-secreting cell lines. Endocrinology 130:167–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastepe M, Pincus JE, Sugimoto T, Tojo K, Kanatani M, Azuma Y, Kruse K, Rosenbloom AL, Koshiyama H, Jüppner H 2001 Positional dissociation between the genetic mutation responsible for pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib and the associated methylation defect at exon A/B: evidence for a long-range regulatory element within the imprinted GNAS1 locus. Hum Mol Genet 10:1231–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Nanclares GP, Fernández-Rebollo E, Santin I, García-Cuartero B, Gaztambide S, Menéndez E, Morales MJ, Pombo M, Bilbao JR, Barros F, Zazo N, Ahrens W, Jüppner H, Hiort O, Castano L, Bastepe M 2007 Epigenetic defects of GNAS in patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism and mild features of Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:2370–2373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller PY, Janovjak H, Miserez AR, Dobbie Z 2002 Processing of gene expression data generated by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Biotechniques 32:1372–1374, 1376, 1378–1379 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee AC, Carreras I, Hossain L, Ryu H, Klein WL, Oddo S, LaFerla FM, Jenkins BG, Kowall NW, Dedeoglu A 2008 Ibuprofen reduces Aβ, hyperphosphorylated τ and memory deficits in Alzheimer mice. Brain Res 1207:225–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedegaertner PB, Bourne HR, von Zastrow M 1996 Activation-induced subcellular redistribution of Gsα. Mol Biol Cell 7:1225–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastepe M, Weinstein LS, Ogata N, Kawaguchi H, Jüppner H, Kronenberg HM, Chung UI 2004 Stimulatory G protein directly regulates hypertrophic differentiation of growth plate cartilage in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:14794–14799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carninci P, Kasukawa T, Katayama S, Gough J, Frith MC, Maeda N, Oyama R, Ravasi T, Lenhard B, Wells C, Kodzius R, Shimokawa K, Bajic VB, Brenner SE, Batalov S, Forrest AR, Zavolan M, Davis MJ, Wilming LG, Aidinis V, Allen JE, Ambesi-Impiombato A, Apweiler R, Aturaliya RN, Bailey TL, et al. 2005 The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science 309:1559–1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Yu S, Litman D, Chen W, Weinstein LS 2000 Identification of a methylation imprint mark within the mouse Gnas locus. Mol Cell Biol 20:5808–5817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes C, Arnaud P, Gordon E, Dean W, Coar EA, Williamson CM, Feil R, Peters J, Kelsey G 2003 Epigenetic properties and identification of an imprint mark in the Nesp-Gnasxl domain of the mouse Gnas imprinted locus. Mol Cell Biol 23:5475–5488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalovsky D, Refojo D, Liberman AC, Hochbaum D, Pereda MP, Coso OA, Stalla GK, Holsboer F, Arzt E 2002 Activation and Induction of NUR77/NURR1 in corticotrophs by CRH/cAMP: involvement of calcium, protein kinase A, and MAPK pathways. Mol Endocrinol 16:1638–1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levis MJ, Bourne HR 1992 Activation of the α subunit of Gs in intact cells alters its abundance, rate of degradation, and membrane avidity. J Cell Biol 119:1297–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedegaertner PB, Bourne HR 1994 Activation and depalmitoylation of Gsα. Cell 77:1063–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein LS, Shenker A, Gejman PV, Merino MJ, Friedman E, Spiegel AM 1991 Activating mutations of the stimulatory G protein in the McCune-Albright syndrome. N Engl J Med 325:1688–1695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwindinger WF, Francomano CA, Levine MA 1992 Identification of a mutation in the gene encoding the α subunit of the stimulatory G protein of adenylyl cyclase in McCune-Albright syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:5152–5156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Vu TH, Ulaner GA, Yang Y, Hu JF, Hoffman AR 2004 Activating and silencing histone modifications form independent allelic switch regions in the imprinted Gnas gene. Hum Mol Genet 13:741–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell AC, Felsenfeld G 2000 Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature 405:482–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hark AT, Schoenherr CJ, Katz DJ, Ingram RS, Levorse JM, Tilghman SM 2000 CTCF mediates methylation-sensitive enhancer-blocking activity at the H19/Igf2 locus. Nature 405:486–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K 2007 High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129:823–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanko DS, Thiyagarajan MM, Wedegaertner PB 2000 Interaction with Gβγ is required for membrane targeting and palmitoylation of Gα(s) and Gα(q). J Biol Chem 275:1327–1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransnäs LA, Svoboda P, Jasper JR, Insel PA 1989 Stimulation of β-adrenergic receptors of S49 lymphoma cells redistributes the α subunit of the stimulatory G protein between cytosol and membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86:7900–7903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward BE, Barlier A, Korbonits M, Grossman A, Jacquet P, Enjalbert A, Bonthron DT 2001 Imprinting of the G(s)α gene GNAS1 in the pathogenesis of acromegaly. J Clin Invest 107:R31–R36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani G, Bondioni S, Lania AG, Corbetta S, de Sanctis L, Cappa M, Di Battista E, Chanson P, Beck-Peccoz P, Spada A 2004 Parental origin of Gsα mutations in the McCune-Albright syndrome and in isolated endocrine tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:3007–3009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michienzi S, Cherman N, Holmbeck K, Funari A, Collins MT, Bianco P, Robey PG, Riminucci M 2007 GNAS transcripts in skeletal progenitors: evidence for random asymmetric allelic expression of Gsα. Hum Mol Genet 16:1921–1930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Gavrilova O, Chen H, Lee R, Liu J, Pacak K, Parlow AF, Quon MJ, Reitman MJ, Weinstein LS 2000 Paternal versus maternal transmission of a stimulatory G-protein α subunit knockout produces opposite effects on energy metabolism. J Clin Invest 105:615–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan FS, Shore EM 2000 Progressive osseous heteroplasia. J Bone Miner Res 15:2084–2094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore EM, Ahn J, Jan de Beur S, Li M, Xu M, Gardner RJ, Zasloff MA, Whyte MP, Levine MA, Kaplan FS 2002 Paternally inherited inactivating mutations of the GNAS1 gene in progressive osseous heteroplasia. N Engl J Med 346:99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust RA, Shore EM, Stevens CE, Xu M, Shah S, Phillips CD, Kaplan FS 2003 Progressive osseous heteroplasia in the face of a child. Am J Med Genet A 118:71–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan I, Hamada T, Hardman C, McGrath JA, Child FJ 2004 Progressive osseous heteroplasia resulting from a new mutation in the GNAS1 gene. Clin Exp Dermatol 29:77–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adegbite NS, Xu M, Kaplan FS, Shore EM, Pignolo RJ 2008 Diagnostic and mutational spectrum of progressive osseous heteroplasia (POH) and other forms of GNAS-based heterotopic ossification. Am J Med Genet A 146A:1788–1796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy MC, Jan De Beur SM, Yandow SM, McAlister WH, Shore EM, Kaplan FS, Whyte MP, Levine MA 2000 Deficiency of the α-subunit of the stimulatory G protein and severe extraskeletal ossification. J Bone Miner Res 15:2074–2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand IM, Hub RS, Shore EM, Kaplan FS, Dimeglio LA 2007 Progressive osseous heteroplasia-like heterotopic ossification in a male infant with pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ia: a case report. Bone 40:1425–1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]