Abstract

Ghrelin, a gastric hormone, provides a hunger signal to the central nervous system to stimulate food intake. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is an intracellular fuel sensor critical for cellular energy homeostasis. Here we showed the reciprocal relationship of gastric mTOR signaling and ghrelin during changes in energy status. mTOR activity was down-regulated, whereas gastric preproghrelin and circulating ghrelin were increased by fasting. In db/db mice, gastric mTOR signaling was enhanced, whereas gastric preproghrelin and circulating ghrelin were decreased. Inhibition of the gastric mTOR signaling by rapamycin stimulated the expression of gastric preproghrelin and ghrelin mRNA and increased plasma ghrelin in both wild-type and db/db mice. Activation of the gastric mTOR signaling by l-leucine decreased the expression of gastric preproghrelin and the level of plasma ghrelin. Overexpression of mTOR attenuated ghrelin promoter activity, whereas inhibition of mTOR activity by overexpression of TSC1 or TSC2 increased its activity. Ghrelin receptor antagonist d-Lys-3-GH-releasing peptide-6 abolished the rapamycin-induced increment in food intake despite that plasma ghrelin remained elevated. mTOR is therefore a gastric fuel sensor whose activity is linked to the regulation of energy intake through ghrelin.

The mTOR signaling system in gastric endocrine cells functions as a peripheral fuel sensor to alter the expression of ghrelin which, in turn, acts on hypothalamic neurons to regulate food intake.

Obesity, a disease in which excess body fat accumulates to an extent that health is negatively affected, occurs when caloric intake persistently outpaces energy expenditure. Food intake is inhibited by a group of anorexigenic hormones including leptin, insulin, peptide YY, and cholecystokinin (1). The only currently identified circulating orexigenic hormone is ghrelin. Plasma ghrelin levels increase with fasting and decrease after feeding, in a pattern indicating that ghrelin is involved in meal initiation (2). Ghrelin levels are negatively correlated with body mass index (3). These observations suggest that nutritional status and food intake affect the production and secretion of ghrelin. The molecular mechanisms by which ghrelin-producing cells sense nutrient intake and regulate ghrelin expression and secretion are currently unknown. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a highly conserved serine-threonine kinase. mTOR has been reported to serve as an intracellular ATP sensor (4). In vitro studies have demonstrated that cellular levels of ATP increase mTOR signaling. Aberrant mTOR activity is linked to the development of cancer, diabetes, and obesity (5,6). Significant elevation of mTOR signaling has been observed in liver and skeletal muscle of insulin-resistant obese rats maintained on a high-fat diet (6). In contrast, absence of the mTOR downstream target ribosomal protein S6 (S6) kinase 1 protects against diet-induced obesity and improves insulin sensitivity in mice (7). A study by Cota et al. (8) reported that mTOR signaling in hypothalamic neurons is involved in neuronal sensing of nutrient availability and regulates food intake and energy balance. These observations suggest that mTOR plays an important role in central neuronal control of nutrient intake and energy balance.

The means by which peripheral cellular mTOR signaling is integrated with hypothalamic neuronal activity is unclear. Previous studies have shown that down-regulation of mTOR signaling by rapamycin results in a significant decrease in leptin production by adipocytes (9). We sought to demonstrate that mTOR regulates the production of ghrelin, which in turn acts to initiate food intake. To test this hypothesis, a series of studies were performed to detect the presence of mTOR signaling molecules in the gastric mucosa, to demonstrate that gastric mTOR signaling is altered by changes in energy status such as fasting and obesity and to demonstrate that alteration in the gastric mTOR activity affects the expression and secretion of ghrelin.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Rapamycin, mouse anti-β-actin antibody, goat antirabbit fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated IgG, and goat antimouse Texas Red-conjugated IgG were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Dimethylsulfoxide, leucine, and atropine were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). d-Lys-3-GH-releasing peptide-6 (d-Lys-3-GHRP-6) and the ghrelin enzyme immunoassay kit were from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Burlingame, CA). Aprotinin was purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Pittsburgh, PA). Eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF)-4E, phospho-S6, phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) rabbit monoclonal antibody, and mTOR rabbit monoclonal antibody were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Mouse anti-preproghrelin was purchased from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA). IRDye-conjugated affinity-purified antirabbit, antimouse IgGs were purchased from Rockland (Gilbertsville, PA). Trizol reagent, the reverse transcription (RT) system, luciferase assay kit, and β-galactosidase enzyme assay kit were from Promega Inc. (Madison, WI). Lipofectamine was purchased from Invitrogen Inc. (Carlsbad, CA).

Animals

Twelve-week-old male C57BL/6J mice (20–25 g) and 12- to 16-wk-old male db/db or db/m mice (45–50 g) were used in the present study. Mice were housed in standard plastic rodent cages and maintained at a regulated environment (24 C, 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle with lights on at 0700 h). Regular chow and water were available ad libitum unless specified otherwise. All animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Peking University. All mice were killed by overdose of CO2 inhalation.

Double-labeling immunohistochemistry

C57BL/6J mice were deeply anesthetized using pentobarbital, perfused transcardially with 20 ml 0.1 m PBS (pH 7.4), followed by 20 ml 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The whole stomach was quickly removed and opened along the greater curvature and rinsed thoroughly with PBS to remove attached debris. The tissues were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, embedded in wax, and sectioned at 6 μm. Paraffin-embedded sections were dewaxed, rehydrated, and rinsed in PBS. After boiling for 10 min in 0.01 mol/liter sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0), sections were blocked in 5% goat preimmune serum in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated overnight with a mixture of rabbit phospho-mTOR antibody (Ser2448) (1:50) and mouse monoclonal antibody to preproghrelin (3 μg/ml). Tissue sections were then incubated at 22 C for 2 h with a mixture of the following secondary antibodies: goat antirabbit fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated IgG (1:100) and goat antimouse Texas Red-conjugated IgG (1:100). Controls included substituting primary antibodies with mouse IgG or rabbit IgG.

Ghrelin and phospho-mTOR-positive cells were evaluated using the Image Plus software to quantify the fluorescent intensity inside the cells. Cells with fluorescent intensity of 150% or greater of tissue background were considered positive. A total of 20 tissue sections from five mice were evaluated.

Measurements of plasma ghrelin

Blood samples were transcardially collected after anesthesia in the presence of aprotinin (2 μg/ml) and EDTA (1 mg/ml). Plasma was stored at −70 C before use. Total ghrelin was measured using an enzyme immunoassay kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Gastric total RNA was isolated using the Trizol reagent. RT was performed using the RT system according to the manufacturer’s instruction. PCR was conducted in a 25-μl volume containing 2.5 ng cDNA, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm dNTPs, 0.2 μm each primer, 1.25 U AmpliTaq Polymerase and 1 μl 800× diluted SYBR Green I stock using the Mx3000 multiplex quantitative PCR system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The PCR program was as follows: hold at 95 C for 5 min and then 95 C for 15 sec, 60 C for 30 sec, and 72 C for 1 min. Melting-curve analysis was from 60–95 C at 0.2 C/sec with Optics Ch1 On. mRNA expression was quantified using the comparative cross-threshold (CT) method. The CT value of the housekeeping gene GAPDH was subtracted from the CT value of the target gene to obtain ΔCT. The normalized fold changes of ghrelin and ghrelin O-acyltransferase (GOAT) mRNA expression are expressed as 2−ΔΔCT, where ΔΔCT = ΔCT sample − ΔCT control.

Primers used in this study were mouse ghrelin (accession no. NM_021488) sense 5′-CCATCTGCAGTTTGCTGCTA-3′ and antisense 5′-GCAGTTTAGCTGGTGGCTTC-3′, GOAT (accession no. EU518496) sense 5′-GTGAGTGCTGGAGCTGGACTG-3′ and antisense 5′-TGAGCCACAGAGCTGTGCTTC-3′, GAPDH (accession no. M32599) sense 5′-ATGACATCAAGAAGGTGGTG-3′ and antisense 5′-CATACCAGGAAATGAGCTTG-3′.

Western blot analysis

The gastric fundus was quickly harvested, rinsed thoroughly with PBS, and then homogenized on ice in the lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl; 15 mm EGTA; 100 mm NaCl; 0.1% Triton X-100 supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 7.5). After centrifugation for 10 min at 4 C, the supernatant was used for Western blot analysis. Protein concentration was measured by Bradford’s method. A total of 80 μg protein from each sample was loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with 5% fat-free milk in Tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20, followed by incubation overnight at 4 C with the primary antibodies. Specific reaction was detected using IRDye-conjugated second antibody and visualized using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Construction of human ghrelin promoter-luciferase expression vectors

A 3143-bp segment of the 5′-upstream regulatory region of the human ghrelin gene (−3161/−18, GenBank accession No. NC_000003.10) was cloned by PCR amplification using human genomic DNA (BD Biosciences) (forward primer, 5′-AGGTGGCAGGCCCTCAAGAGACCCGCAACAGA-3′; reverse primer, 5′-AGACAGGTGGGCCTGGGGGAGAGAGGGTCT-3′) and subcloned into promoterless luciferase expression vector pGL3-Basic (Promega).

Reporter assays

HEK 293 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 air. For transient transfection, cells were plated onto 24-well tissue culture plates at optimal densities and grown for 24 h. Cells were then transfected with the ghrelin promoter-luciferase reporter gene constructs (500 ng), which were mixed with or without one of the following constructs: human mTOR (500 ng), human tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC1, 500 ng), rat TSC2 (500 ng), pcDNA3.1 (500 ng), and an internal control pSV-β-galactosidase (25 ng) per well using Lipofectamine reagent according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Cells were either harvested 48 h later or grown overnight and then treated with chemicals for 24 h. In parallel experiments, empty vector pGL3 was used as control. All cells were rinsed with PBS and lysed in 100 μl passive lysis buffer. Cell lysates were analyzed for luciferase activity with the dual-luciferase reporter assay system using a luminometer (Monolight 2010; Analytical Luminescence Laboratory, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. β-Galactosidase activity was measured according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as means ± sem. Statistical differences were evaluated by two-way ANOVA and Newman-Student-Keuls test. Comparisons between two groups involved use of the Student’s t test. P value <0.05 denotes statistical significance. Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to determine the strength of the linear relationship between gastric preproghrelin levels and phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) and phospho-S6, respectively.

Results

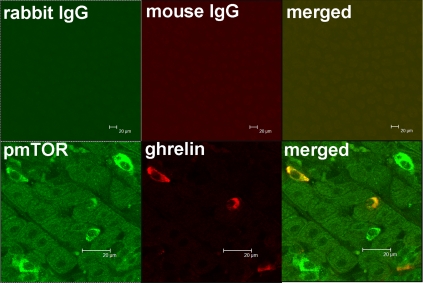

Expression of mTOR in gastric mucosa

To determine whether mTOR signaling molecules are expressed in gastric mucosa, double immunohistochemistry was used to localize phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) in the mouse gastric mucosa. Antibody recognizing phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) demonstrated strong positive reactivity in cells also reactive for ghrelin in the lower one third of the mucosa of the fundus (Fig. 1), whereas control antibody produced no signal. Virtually 100% of ghrelin-positive cells stained positively for phospho-mTOR. Conversely, 28 ± 5% of 720 phospho-mTOR-positive gastric mucosal cells were positive for ghrelin.

Figure 1.

Colocalization of phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) and ghrelin in the mouse fundic mucosa. Upper panel, Control antibodies showed no staining; lower panel, high-resolution images depicting phospho-mTOR (pmTOR) (green) and ghrelin (red) in gastric mucosal cells. Merged image illustrates colocalization of pmTOR and ghrelin (orange). Bar, 20 μm.

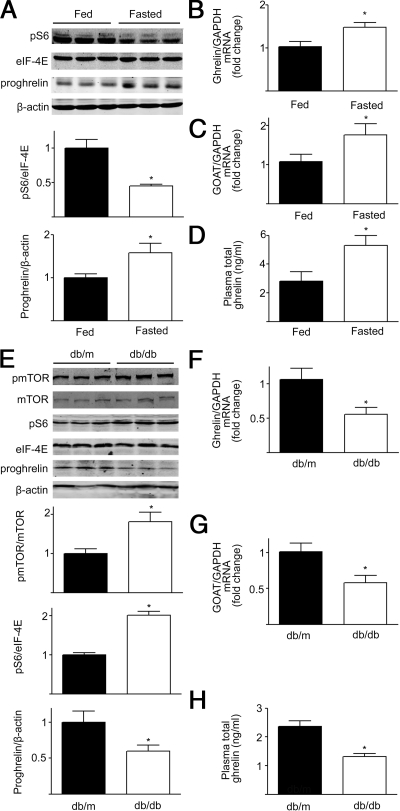

Reciprocal effects of fasting on gastric mTOR signaling and ghrelin production

To examine the effect of fasting on mTOR signaling and ghrelin production, 12-wk-old male C57BL/6J mice were divided into two groups, a control group in which animals were fed ad libitum and a group in which mice were fasted for 48 h. Phosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein, a downstream target of mTOR (5,8), in gastric fundic mucosa was decreased in fasted mice relative to fed animals (Fig. 2A). Gastric ghrelin mRNA levels were significantly increased in fasted mice relative to control animals (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Modulation of mTOR signaling by energy status and obesity. A, Representative Western blot from fed mice or mice fasted for 48 h. Gastric phospho-S6 (pS6) and preproghrelin (proghrelin) were blotted as described in Materials and Methods. β-Actin and eIF-4E were used as loading controls. Quantification of image analysis of gastric S6 phosphorylation and preproghrelin expression is expressed as mean ± sem. B and C, Results of quantitative PCR analysis of ghrelin (B) and GOAT (C) mRNA are expressed as fold increase from fed condition using glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as loading control. D, Plasma total ghrelin in fed and fasted mice was measured as described in detail in Materials and Methods, and results are expressed as mean ± sem. Six stomachs were examined for each condition. *, P < 0.05 vs. mice in the fed condition. E, Representative Western blot from wild-type (db/m) or obese (db/db) mice. Gastric phospho-mTOR (pmTOR), phospho-S6 (pS6) and preproghrelin (proghrelin) were examined. β-actin and eIF-4E were used as loading controls. Quantification of image analysis of gastric mTOR and pS6 phosphorylation, and preproghrelin is expressed as mean ± sem. F and G, Results of quantitative PCR analysis of ghrelin (F) and GOAT mRNA (G) expression are expressed as fold increase from wild-type condition using GAPDH as loading control. H, Plasma total ghrelin in wild-type and obese mice was measured as described in Materials and Methods, and results are expressed as mean ± sem. Six stomachs were examined for each condition. *, P < 0.05 vs. wild-type mice.

GOAT is a member of the family of membrane-bound O-acyltransferases (MBOATs). GOAT catalyzes the octanoylation of ghrelin, which is critical for the binding of ghrelin to the GH secretagogue receptor GHSR1a (10). Gastric GOAT mRNA levels increased significantly in fasted mice relative to fed mice (Fig. 2C). In contrast to changes in phosphorylated S6, gastric preproghrelin levels were significantly increased after fasting as were levels of circulating ghrelin (Fig. 2, A and D). A significant negative correlation was found between gastric levels of phospho-S6 and preproghrelin (Pearson’s r = −0.6; P = 0.035).

Up-regulation of gastric mTOR signaling and down-regulation of ghrelin production in obese mice

The effects of long-term changes in nutritional status on gastric mTOR signaling were examined using the 12- to 16-wk-old male db/db obese mouse model. As shown in Fig. 2E, there was a significant increase in gastric phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) and phospho-S6 expression in db/db mice relative to the db/m animals. In contrast to changes in mTOR signaling, decrements in gastric ghrelin mRNA and GOAT mRNA were observed in db/db mice relative to the db/m animals (Fig. 2, F and G). Both gastric preproghrelin and plasma ghrelin levels demonstrated significant decreases in the db/db mice compared with db/m mice (Fig. 2, E and H). A significant negative correlation was found between the gastric preproghrelin and phosphorylation levels of phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) (Pearson’s r = −0.7; P = 0.017) or phospho-S6 (Pearson’s r = −0.6; P = 0.048).

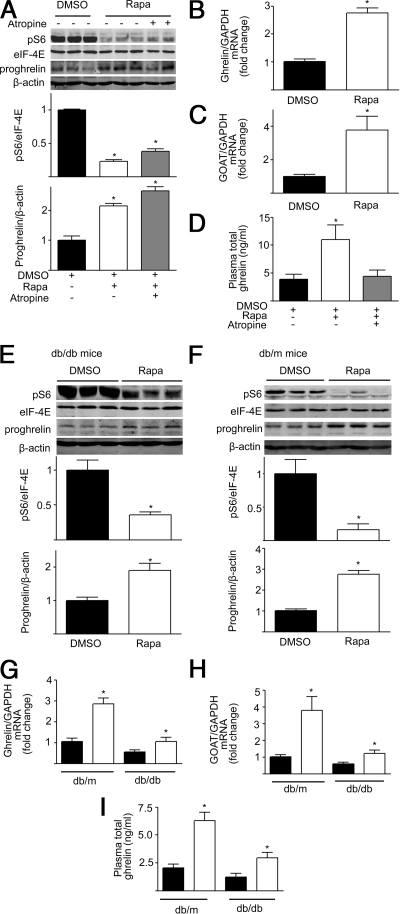

Increased ghrelin production by inhibition of gastric mTOR signaling

If mTOR signaling is linked to the production of ghrelin, then changes in gastric mTOR activity would be predicted to alter the production and secretion of ghrelin. The effects of rapamycin, a well-characterized mTOR inhibitor, were examined in C57BL/6J mice. Twelve-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were divided into three groups: control [dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)] injection, rapamycin (1 mg/kg) injection ip for 6 d, and a group in which atropine (1 mg/kg) was administered ip 15 min before rapamycin. Intraperitoneal injection of rapamycin (1 mg/kg) for 6 d significantly decreased gastric phospho-S6 (Ser235/236), a marker of mTOR activity (Fig. 3A). The decrease in gastric mTOR signaling in mice treated with rapamycin was associated with a significant increase in gastric ghrelin mRNA and GOAT mRNA expression, gastric preproghrelin levels, and circulating ghrelin compared with control mice (Fig. 3, A–D).

Figure 3.

Rapamycin regulates gastric mTOR signaling and ghrelin production. A, Representative Western blots from mice that received ip injection of DMSO, rapamycin (Rapa,1 mg/kg), or rapamycin plus atropine (1 mg/kg). Phospho-S6 (pS6) and preproghrelin (proghrelin) in gastric mucosa were detected using specific antibodies. β-Actin and eIF-4E were used as loading controls. Quantification of image analysis of gastric pS6 and preproghrelin is expressed as mean ± sem. B and C, Results of quantitative PCR analysis of ghrelin (B) and GOAT mRNA (C) are expressed as fold increase from control using glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as loading control. D, Plasma total ghrelin was measured as described in detail in Materials and Methods, and results expressed as mean ± sem. Six stomachs were examined for each condition. *, P < 0.05 vs. mice receiving DMSO. E and F, Representative Western blots from obese (db/db) (E) and wild-type (db/m) (F) mice treated with DMSO or rapamycin. Phospho-S6 (pS6) and preproghrelin (proghrelin) in gastric mucosa were detected using specific antibodies. β-Actin and eIF-4E were used as loading controls. Quantification of image analysis of gastric pS6 and preproghrelin is expressed as mean ± sem. G and H, Results of quantitative PCR analysis of ghrelin (G) and GOAT (H) mRNA are expressed as fold increase from wild-type condition using GAPDH as loading control. I, Plasma total ghrelin is expressed as mean ± sem. *, P < 0.05 vs. wild-type mice. Six stomachs were examined for each condition.

Atropine was used to block cholinergic input to the stomach (11). As shown in Fig. 3A, atropine had no effect on rapamycin inhibition of gastric S6 phosphorylation or preproghrelin levels but abolished increases in circulating ghrelin induced by rapamycin (Fig. 3D). Cholinergic innervation of the gastric mucosa is important in release of mucosal ghrelin into the circulation but not the up-regulation of gastric preproghrelin by rapamycin (Fig. 3A).

The next experiments investigated whether inhibition of gastric mTOR signaling by rapamycin affects ghrelin expression in obese mice (12- to 16-wk-old male db/db mice). As shown in Fig. 3E, ip injection of rapamycin significantly inhibited gastric phospho-S6 (Ser235/236) levels in db/db mice. The decrement in the gastric mTOR signaling was accompanied by significant increases in gastric ghrelin mRNA and GOAT mRNA levels, tissue preproghrelin content, and circulating ghrelin in db/db mice treated with rapamycin (Fig. 3, E and G–I). Rapamycin-induced increases in gastric ghrelin mRNA and GOAT mRNA levels, tissue preproghrelin content, and circulating ghrelin were less in obese mice than observed in db/m animals (Fig. 3, E–I).

Decrease in ghrelin production by activation of gastric mTOR signaling

Because inhibition of mTOR signaling in the gastric mucosa leads to up-regulation of ghrelin expression and increase in ghrelin secretion, it is expected that activation of mTOR signaling in the gastric mucosa would suppress production of ghrelin. Intraperitoneal administration of l-leucine (0.45 g/kg for 6 d), a branched-chain amino acid that has been documented to activate mTOR signaling (12), significantly increased phospho-S6 levels (Fig. 4A), with decreased gastric ghrelin mRNA, GOAT mRNA levels, gastric preproghrelin content, and plasma ghrelin in C57 BL/6J mice compared with controls (Fig. 4, A–D).

Figure 4.

l-Leucine regulates mTOR signaling and ghrelin expression. A, Representative Western blot from mice that received ip injection of DMSO, rapamycin (1 mg/kg), or l-leucine (0.45 g/kg). Phospho-S6 (pS6) and preproghrelin (proghrelin) in gastric mucosa were detected using specific antibodies. β-Actin and eIF-4E were used as loading controls. Quantification of image analysis of gastric pS6 and preproghrelin is expressed as mean ± sem. B and C, Results of quantitative PCR analysis of ghrelin (B) and GOAT mRNA (C) are expressed as fold increase from control. D, Plasma total ghrelin is expressed as mean ± sem. *, P < 0.05 vs. mice receiving DMSO. Six stomachs were examined for each condition. GAPDH, Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Rapa, rapamycin.

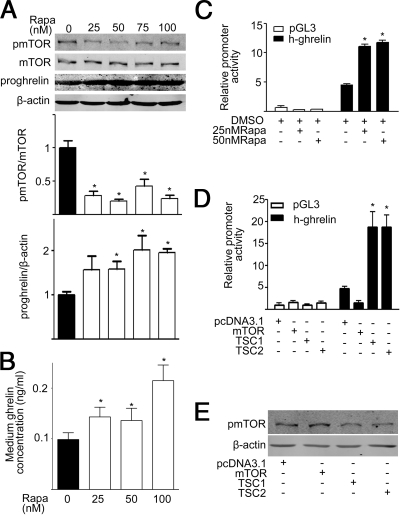

In vitro effects of rapamycin on ghrelin production and the activity of ghrelin promoter

The in vitro effects of rapamycin on ghrelin production were examined using 3T3-L1 cells in which ghrelin expression and secretion have been reported (13). Consistent with in vivo studies, rapamycin significantly decreased phosphorylation of mTOR and increased preproghrelin content in 3T3-L1 cells (Fig. 5A). Rapamycin dose-dependently increased ghrelin released into the media (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Rapamycin (Rapa) regulates mTOR signaling and ghrelin expression in vitro. A, Representative Western blot of gastric phospho-mTOR (pmTOR), preproghrelin (proghrelin), and β-actin in 3T3-L1 cells exposed to varying concentrations of rapamycin. Quantification of image analysis of gastric pmTOR (upper right panel) and preproghrelin (lower left panel) is expressed as mean ± sem; n = 3. *, P < 0.05 vs. control. B, Medium total ghrelin concentration in response to varying concentrations of rapamycin. n = 3. *, P < 0.05 vs. control. C, Relative luciferase activity in HEK 293 cells transfected with ghrelin promoter-luciferase plasmid after exposure to varying concentrations of rapamycin. n = 3. *, P < 0.05 vs. control. D, Relative luciferase activity in HEK 293 cells cotransfected with ghrelin promoter-luciferase plasmid and 500 ng of one of the following plasmids: human mTOR (Flag-mTOR), human TSC1 (Myc-TSC1), rat TSC2 (HA-TSC2), pcDNA3.1, and an internal control pSV-β-galactosidase (25 ng). Results are expressed as mean ± sem. E, Representative Western blot of phospho-mTOR (pmTOR) and β-actin. n = 3. *, P < 0.05 vs. control.

To determine whether mTOR signaling modulates the transcription of the ghrelin gene, we assayed the activity of the approximately 3-kb human ghrelin promoter. As shown in Fig. 5C, rapamycin significantly increased luciferase activity in HEK 293 cells transfected with ghrelin promoter-luciferase plasmid relative to control, suggesting that down-regulation of mTOR signaling leads to an increase in ghrelin promoter activity. Consistent with this observation, overexpression of mTOR in HEK293 cells decreased the ghrelin promoter activity (Fig. 5D). To further confirm the effect of mTOR on ghrelin promoter activity, we inhibited the mTOR activity by overexpression of its negative regulator: the TSC gene products TSC1 and TSC2. TSC1 and TSC2 are tumor suppressor genes that are mutated in the disease TSC. The proteins TSC1 and TSC2 form a tight complex in the cell to negatively regulate mTOR activity, and the presence of both proteins is required for the TSC1/2 heterodimer to function (5). As shown in Fig. 5D, overexpression of TSC1 or TSC2 significantly increased the ghrelin promoter activity (Fig. 5D). Both TSC1 and TSC2 function to inhibit mTOR signaling (Fig. 5E).

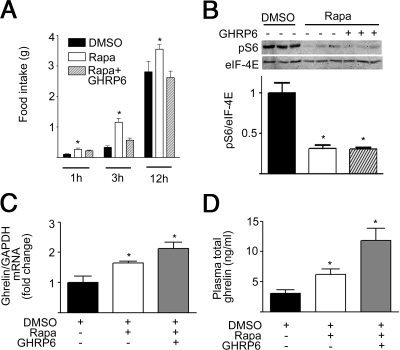

Ghrelin receptor antagonist blocks the orexigenic effect of rapamycin

To investigate whether rapamycin affects food intake and whether such an effect is mediated by ghrelin, 12-wk-old male C57BL/6J mice were divided into three groups: control (DMSO), rapamycin (1 mg/kg in DMSO ip injection), and ghrelin receptor antagonist d-Lys-3-GHRP-6 (200 nmol/mouse ip 2 min before rapamycin injection) (14). Food intake was recorded for 12 h in the dark cycle. Food intake was significantly increased after ip administration of rapamycin (Fig. 6A). d-Lys-3-GHRP-6 blocked the orexigenic effect of rapamycin, with food intake not significantly different from controls. Intraperitoneal injection of rapamycin significantly decreased gastric phospho-S6, which could not be blocked by d-Lys-3-GHRP-6 (Fig. 6B). Rapamycin-induced increments in gastric ghrelin mRNA and plasma ghrelin were not affected by administration of d-Lys-3-GHRP6 (Fig. 6, C and D), indicating that antagonism of ghrelin receptor does not interfere the effect of rapamycin on the secretion of ghrelin.

Figure 6.

Rapamycin affects food intake via circulating ghrelin. A, Food intake in C57BL/6J mice receiving DMSO, rapamycin (Rapa; 1 mg/kg ip), or ghrelin receptor antagonist d-Lys-3-GHRP-6 (GHRP6, 200 nmol/mouse ip 2 min before rapamycin injection). Error bars indicate sem. B, Representative Western blots of phospho-S6 (pS6) and eIF-4E. Quantification of image analysis of gastric pS6 is expressed as mean ± sem. C, Results of quantitative PCR analysis of gastric ghrelin mRNA are expressed as fold increase from control. D, Plasma total ghrelin for each treatment group. *, P < 0.05 vs. control. Six mice were examined for each condition. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Discussion

The major finding of the present study is that the mTOR signaling system in gastric endocrine cells functions as a peripheral fuel sensor to alter the expression of ghrelin, which in turn acts on hypothalamic neurons to regulate food intake. This conclusion is supported by the following distinct observations: 1) the active form of mTOR, phospho-mTOR, is expressed in gastric mucosal ghrelin cells; 2) mTOR phosphorylation in the gastric mucosa is down-regulated by fasting and up-regulated in db/db obese mice; 3) a reciprocal relationship exists between gastric mTOR signaling and the expression and secretion of ghrelin during changes in energy status; 4) inhibition of gastric mTOR signaling leads to increased expression of ghrelin mRNA, GOAT mRNA, tissue preproghrelin content, and circulating ghrelin; 5) conversely, activation of gastric mTOR signaling suppresses the expression and secretion of ghrelin; 6) overexpression of mTOR decreases ghrelin promoter activity, whereas blocking mTOR signaling by TSC1 or TSC2 increases its activity; and 7) antagonism of ghrelin receptor abolishes increases in food intake induced by rapamycin without altering the expression or secretion of ghrelin.

Ghrelin, a 28-amino-acid gastric peptide, is the only currently identified circulating hormone that is able to induce the sensation of hunger and to initiate food intake via a mechanism involving the central nervous system (15,16,17,18,19,20). Ghrelin has wide distribution, but the predominant site of production is the stomach (21). Morphologically, ghrelin-positive cells are not in continuity with the gastric lumen (21). This structure is interpreted to mean that ghrelin cells respond to signals received via the basolateral membrane in close apposition to the capillary network of the lamina propria.

Ghrelin is initially produced within neurocrine cells as a 117-amino-acid preproghrelin and then processed by preprotein convertase 1/3 to a 28-amino-acid peptide (22). Ghrelin is acylated by the enzyme GOAT (10). The majority of circulating ghrelin exists as des-acyl ghrelin, identical to acyl-ghrelin except that the third amino acid serine is not acylated (17). About one tenth of circulating ghrelin is acyl-ghrelin, which carries a unique octanoyl structure at the third amino acid serine residue. Acyl-ghrelin is well characterized as a potent stimulator for food intake, whereas the effect of des-acyl ghrelin on energy balance is conflicting (23). Although expression and secretion of ghrelin have been reported to be subject to changes in nutrient ingestion and to adiposity signals such as leptin and insulin, the molecular details of this regulation remain unknown (24,25,26). Some studies have suggested that expression and secretion of ghrelin is primarily controlled by the central nervous system including the hypothalamus (11,27). The current study demonstrates that direct control of ghrelin expression and secretion can occur at the level of gastric mucosa and that the mTOR signaling system is a crucial control point in ghrelin expression and secretion.

mTOR has been referred to as a fuel sensor due to its regulatory properties for cellular energy homeostasis. Two mTOR complexes are known to exist. mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) is responsible for nutrient-sensing functions and is composed of mTOR, G protein-subunit-like protein, and raptor. mTORC2 phosphorylates Akt protein kinase B and contains mTOR and a protein called rictor (28). The mTOR pathway is activated by positive energy states characterized by elevated ratios of ATP/AMP (4). The mTOR pathway is also activated by glucose, high levels of insulin, and amino acids (28). l-Leucine is a specific activator of mTOR in vivo, whereas l-valine, another branched-chain amino acid does not stimulate mTOR signaling (8,12). Downstream targets of mTOR include S6 kinases, S6, and eIF-4E binding protein 1 (5,28).

Recent studies by Cota et al. (8) suggest the existence of the mTOR regulatory point in hypothalamic neurons that directly regulate energy intake. In the rat hypothalamus, mTOR signaling components colocalized with the feeding peptides neuropeptide Y and proopiomelanocortin in the arcuate nucleus. The hormone leptin decreased food intake and increased hypothalamic mTOR activity. The actions of leptin were inhibited by rapamycin. Reciprocally, intracerebroventricular administration of leucine increased mTOR signaling and suppressed food intake and weight gain (8).

Detection of mTOR signaling molecules within gastric ghrelin cells suggests that fuel-sensing mechanisms also exist within the gastric mucosa. In mice, modulation of mTOR activity in the gastric mucosa by rapamycin does not require cholinergic input from the central nervous system because atropine, which blocks cholinergic neurotransmission, did not alter the increase in the expression of ghrelin induced by rapamycin.

Alterations in gastric mTOR signaling during fasting and obesity suggest that gastric ghrelin cells may recognize energy status at the organism level and trigger the coordinate expression and secretion of ghrelin. The reciprocal relationship between gastric mTOR signaling and ghrelin expression was retained in obese db/db mice, although tissue preproghrelin content and circulating levels of ghrelin were decreased relative to lean animals. If the relationship of mTOR signaling to ghrelin exists in normal and obese humans, it might be feasible to target fuel-sensing mechanisms in the gastric mucosa to treat the obesity as an alternative strategy to therapies designed to affect hypothalamic mechanisms.

A crucial feature of feeding behavior is the interaction of peripheral fuel-sensing mechanisms with energy signaling pathways of the hypothalamus, the central nervous system site most essential to nutrient homeostasis. Ghrelin is involved in orexigenic behavior and energy expenditure via two general pathways. Ghrelin acts as a circulating hormone released from the stomach that functions in conjunction with other peripheral signals such as leptin and insulin (29,30,31). Ghrelin also acts as a hypothalamic neuropeptide that modulates both orexigenic neuropeptide Y/agouti-related peptide neurons and anorexigenic proopiomelanocortin neurons (32). The current studies support the concept the ghrelin functions as a bridging signal to integrate peripheral fuel status and the central feeding mechanisms. Consistent with this concept, blocking the function of ghrelin by its receptor antagonist d-Lys-3-GHRP-6 abolished the orexigenic effect of rapamycin.

Recent studies have focused upon the central nervous system, particularly the hypothalamus, in the coordination of intracellular metabolic processes that regulate energy homeostasis at the organism level. Hypothalamic neurons are responsive to acute changes in nutrients such as glucose (33,34) and fatty acids (35,36) and to the chronic adiposity signal leptin (37). These signals are sensed by hypothalamic neurons, leading to the alteration of intracellular signaling pathways such as AMP-activated protein kinase and mTOR, which in turn regulate both neuronal firing rates and transcription of effector molecules (38,39,40). The current study suggests that the gastric mucosa is another critical organ that senses fuel levels and responds by alterations in production and secretion of ghrelin. The existence of a fuel-sensing pathway within the gastric mucosa may also provide opportunities for the therapy of obesity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Kunliang Guan (University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA) for providing human mTOR, human TSC1, and rat TSC2 plasmids.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30890043, 30740096, 30871194, and 30700376) and the 985 Program at Peking University (985-2-097-121) and National Institutes of Health Grant RO1DK043225.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online April 30, 2009

Abbreviations: CT, Comparative cross-threshold; D-Lys-3-GHRP-6, D-Lys-3-GH-releasing peptide-6; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; eIF, eukaryotic initiation factor; GOAT, ghrelin O-acyltransferase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; mTORC, mTOR complex; RT, reverse transcription; S6, ribosomal protein S6; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex.

References

- Murphy KG, Dhillo WS, Bloom SR 2006 Gut peptides in the regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis. Endocr Rev 27:719–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings DE, Purnell JQ, Frayo RS, Schmidova K, Wisse BE, Weigle DS 2001 A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes 50:1714–1719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TschöpM, Weyer C, Tataranni PA, Devanarayan V, Ravussin E, Heiman ML 2001 Circulating ghrelin levels are decreased in human obesity. Diabetes 50:707–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis PB, Jaeschke A, Saitoh M, Fowler B, Kozma SC, Thomas G 2001 Mammalian TOR: a homeostatic ATP sensor. Science 294:1102–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Corradetti MN, Guan KL 2005 Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nat Genet 37:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khamzina L, Veilleux A, Bergeron S, Marette A 2005 Increased activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway in liver and skeletal muscle of obese rats: possible involvement in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Endocrinology 146:1473–1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Um SH, Frigerio F, Watanabe M, Picard F, Joaquin M, Sticker M, Fumagalli S, Allegrini PR, Kozma SC, Auwerx J, Thomas G 2004 Absence of S6K1 protects against age- and diet-induced obesity while enhancing insulin sensitivity. Nature 431:200–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D, Proulx K, Smith KA, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Woods SC, Seeley RJ 2006 Hypothalamic mTOR signaling regulates food intake. Science 312:927–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh C, Han J, Tzatsos A, Kandror KV 2003 Nutrient-sensing mTOR-mediated pathway regulates leptin production in isolated rat adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284:E322–E330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Brown MS, Liang G, Grishin NV, Goldstein JL 2008 Identification of the acyltransferase that octanoylates ghrelin, an appetite-stimulating peptide hormone. Cell 132:387–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DL, Grill HJ, Cummings DE, Kaplan JM 2003 Vagotomy dissociates short- and long-term controls of circulating ghrelin. Endocrinology 144:5184–5187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC, Yoshizawa F, Anthony TG, Vary TC, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR 2000 Leucine stimulates translation initiation in skeletal muscle of postabsorptive rats via a rapamycin-sensitive pathway. J Nutr 130:2413–2419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Zhao L, Lin TR, Chai B, Fan Y, Gantz I, Mulholland MW 2004 Inhibition of adipogenesis by ghrelin. Mol Biol Cell 15:2484–2491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa A, Inui A, Kaga T, Katsuura G, Fujimiya M, Fujino MA, Kasuga M 2003 Antagonism of ghrelin receptor reduces food intake and body weight gain in mice. Gut 52:947–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TschöpM, Smiley DL, Heiman ML 2000 Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature 407:908–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wren AM, Small CJ, Ward HL, Murphy KG, Dakin CL, Taheri S, Kennedy AR, Roberts GH, Morgan DG, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR 2000 The novel hypothalamic peptide ghrelin stimulates food intake and growth hormone secretion. Endocrinology 141:4325–4328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda H, Kojima M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K 2000 Ghrelin and des-acyl ghrelin: two major forms of rat ghrelin peptide in gastrointestinal tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 279:909–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wren AM, Seal LJ, Cohen MA, Brynes AE, Frost GS, Murphy KG, Dhillo WS, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR 2001 Ghrelin enhances appetite and increases food intake in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:5992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toshinai K, Date Y, Murakami N, Shimada M, Mondal MS, Shimbara T, Guan JL, Wang QP, Funahashi H, Sakurai T, Shioda S, Matsukura S, Kangawa K, Nakazato M 2003 Ghrelin-induced food intake is mediated via the orexin pathway. Endocrinology 144:1506–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abizaid A, Liu ZW, Andrews ZB, Shanabrough M, Borok E, Elsworth JD, Roth RH, Sleeman MW, Picciotto MR, TschöpMH, Gao XB, Horvath TL 2006 Ghrelin modulates the activity and synaptic input organization of midbrain dopamine neurons while promoting appetite. J Clin Invest 116:3229–3239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Date Y, Kojima M, Hosoda H, Sawaguchi A, Mondal MS, Suganuma T, Matsukura S, Kangawa K, Nakazato M 2000 Ghrelin, a novel growth hormone-releasing acylated peptide, is synthesized in a distinct endocrine cell type in the gastrointestinal tracts of rats and humans. Endocrinology 141:4255–4261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Cao Y, Voogd K, Steiner DF 2006 On the processing of proghrelin to ghrelin. J Biol Chem [Erratum (2007) 282:2124] 281:38867–38870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares JB, Leite-Moreira AF 2008 Ghrelin, des-acyl ghrelin and obestatin: three pieces of the same puzzle. Peptides 29:1255–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toshinai K, Mondal MS, Nakazato M, Date Y, Murakami N, Kojima M, Kangawa K, Matsukura S 2001 Upregulation of Ghrelin expression in the stomach upon fasting, insulin-induced hypoglycemia, and leptin administration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 281:1220–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CamiñaJP, Carreira MC, Micic D, Pombo M, Kelestimur F, Dieguez C, Casanueva FF 2003 Regulation of ghrelin secretion and action. Endocrine 22:5–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins SC, Gueorguiev M, Korbonits M 2007 Ghrelin, the peripheral hunger hormone. Ann Med 39:116–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanson-Albertsson C, Lindqvist A 2008 Vagotomy and accompanying pyloroplasty down-regulates ghrelin mRNA but does not affect ghrelin secretion. Regul Pept 151:14–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Guan KL 2007 Expanding mTOR signaling. Cell Res 17:666–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno N, Dube MG, Inui A, Kalra PS, Kalra SP 2004 Leptin modulates orexigenic effects of ghrelin and attenuates adiponectin and insulin levels and selectively the dark-phase feeding as revealed by central leptin gene therapy. Endocrinology 145:4176–4184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan DE, Evans ML, Monsod TP, Rife F, Heptulla RA, Tamborlane WV, Sherwin RS 2003 The influence of insulin on circulating ghrelin. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284:E313–E316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdolo G, Lucidi P, Di Loreto C, Parlanti N, De Cicco A, Fatone C, Fanelli CG, Bolli GB, Santeusanio F, De Feo P 2003 Insulin is required for prandial ghrelin suppression in humans. Diabetes 52:2923–2927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HY, Trumbauer ME, Chen AS, Weingarth DT, Adams JR, Frazier EG, Shen Z, Marsh DJ, Feighner SD, Guan XM, Ye Z, Nargund RP, Smith RG, Van der Ploeg LH, Howard AD, MacNeil DJ, Qian S 2004 Orexigenic action of peripheral ghrelin is mediated by neuropeptide Y and agouti-related protein. Endocrinology 145:2607–2612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroya S, Yada T, Shioda S, Takigawa M 1999 Glucose-sensitive neurons in the rat arcuate nucleus contain neuropeptide Y. Neurosci Lett 264:113–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XH, Morris R, Spiller D, White M, Williams G 2001 Orexin a preferentially excites glucose-sensitive neurons in the lateral hypothalamus of the rat in vitro. Diabetes 50:2431–2437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam TK, Schwartz GJ, Rossetti L 2005 Hypothalamic sensing of fatty acids. Nat Neurosci 8:579–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López M, Lage R, Saha AK, Pérez-Tilve D, Vázquez MJ, Varela L, Sangiao-Alvarellos S, Tovar S, Raghay K, Rodríguez-Cuenca S, Deoliveira RM, Castañeda T, Datta R, Dong JZ, Culler M, Sleeman MW, Alvarez CV, Gallego R, Lelliott CJ, Carling D, Tschöp MH, Diéguez C, Vidal-Puig A 2008 Hypothalamic fatty acid metabolism mediates the orexigenic action of ghrelin. Cell Metab 7:389–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Kinzig KP, Aja S, Scott KA, Keung W, Kelly S, Strynadka K, Chohnan S, Smith WW, Tamashiro KL, Ladenheim EE, Ronnett GV, Tu Y, Birnbaum MJ, Lopaschuk GD, Moran TH 2007 Leptin activates hypothalamic acetyl-CoA carboxylase to inhibit food intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:17358–17363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue B, Kahn BB 2006 AMPK integrates nutrient and hormonal signals to regulate food intake and energy balance through effects in the hypothalamus and peripheral tissues. J Physiol 574:73–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claret M, Smith MA, Batterham RL, Selman C, Choudhury AI, Fryer LG, Clements M, Al-Qassab H, Heffron H, Xu AW, Speakman JR, Barsh GS, Viollet B, Vaulont S, Ashford ML, Carling D, Withers DJ 2007 AMPK is essential for energy homeostasis regulation and glucose sensing by POMC and AgRP neurons. J Clin Invest 117:2325–2336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D, Proulx K, Seeley RJ 2007 The role of CNS fuel sensing in energy and glucose regulation. Gastroenterology 132:2158–2168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]