Abstract

Purpose

We studied clinical phenotyping and TEAD1 expression in mice and humans to gain a better understanding of the primary origin in the pathogenesis of circumpapillary dysgenesis of the pigment epithelium.

Design

Observational case series and experimental study.

Participants

Three female patients from an affected family were included for phenotypic study. Mice and human tissues were used for biochemistry and immunohistochemistry studies.

Methods

We performed genetic analyses and longitudinal clinical, imaging, and electrophysiologic studies in a 3-generation family. Western blotting and immunohistochemistry were used to detect TEAD1 expression in mice and human retinal tissues.

Main Outcome Measures

Autofluorescence and optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging were compared and reviewed from 3 patients. TEAD1 expression was compared in different tissues from mice and human samples.

Results

A point mutation at T1261 in TEAD1 was detected in the mother. Autofluorescence and OCT imaging studies revealed choroid is involved earlier than retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). From immunoblot analysis, we discovered that TEAD1 and its cofactors YAP65 and FOXA2 are expressed in the choroid. Immunohistochemical analysis on frozen sections of mouse retina supports immunoblot results.

Conclusions

The primary cellular origin of circumpapillary dysgenesis of the pigment epithelium is within the choroid instead of the pigment epithelium. The loss of the RPE and photoreceptors in later stages of the disease is a secondary consequence of choroidal degeneration. Studies of the downstream targets of TEAD1 in choroidal cells will provide promising new research opportunities for the development of treatments for choroidal diseases.

Circumpapillary dysgenesis of the pigment epithelium1 (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 108985, National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD; available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/; accessed October 30, 2008) is also known as atrophia areata, helicoidal peripapillary chorioretinal degeneration,2,3 choroiditis areata,4 and Sveinsson’s chorioretinal atrophy.3 Clinically, this autosomal dominant disease is characterized by bilateral geographic, helicoid destruction of the choroid, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and photoreceptors. These tongue-like chorioretinal lesions begin in the peripapillary region and radiate centrifugally through the posterior pole, causing blindness when the macula is affected. A recent histopathologic study of an 82-year-old patient suggested that the RPE and outer segments of the photoreceptors were the sites of the primary lesion.5–7 This report of a three-generation family gave us the opportunity to look at the course of the disease in a time-elapsed manner.

TEA domain family member 1 is also known as SV40 transcriptional enhancer factor. The T1261C point mutation in the TEA domain family member 1 gene (TEAD1)8 is linked to circumpapillary dysgenesis of the pigment epithelium and found to be segregated in a large Icelandic founder pedigree.5 The T1261C point mutation results in an Y421H mutation, substituting tyrosine with histidine. Y421H affects a conserved YAP65 binding site in the C-terminus of TEAD1.9 The transcriptional cofactor YAP65 binds to TEAD1 to regulate the activation of the FOXA2 enhancer. Northern blot analysis revealed YAP65 transcription in various human tissues, with a higher expression level in the reproductive organs and small intestine and lower levels in the brain, liver, and spleen.10 It is also expressed in embryonic, neural, and hematopoietic stem cells.11 Expression of TEAD family members (TEADs) and their cofactor YAP65 correlates with regions of FOXA2 activity in E6.5 to E8.5 mouse embryos. Interruption of TEAD function disturbed both FOXA2 expression and the normal development of the mouse notochord.12 Of all 4 TEADs, TEAD1 and TEAD4 has the strongest effect on FOXA2 activation.12

FOXA2, formerly known as hepatic nuclear factor-3-beta, regulates transthyretin expression.13 Transthyretin (also known as thyroxine-binding pre-albumin) is a homotetrameric soluble protein that transports thyroxine (T4) and retinol into the choroid, as well as into the choroid plexus of the cerebral ventricles. The retina-choroid and the choroid plexus-hepatic sinusoids share biochemical and structural similarities. This led us to examine the presence of FOXA2 pathway components in the retina and their possible role in circumpapillary dysgenesis of the pigment epithelium.

In this report, we analyzed genetic, clinical, imaging, electrophysiologic, biochemical, and immunohistochemical studies and provided evidence that TEAD-FOXA2 signaling in the choroid contributes to the development of Sveinsson’s chorioretinal atrophy.

Materials and Methods

Phenotypic Studies

Three female patients from an affected family (ages 3, 38, 68 years) were enrolled with the approval of the institutional review board protocol AAAB6560 at Columbia University. The tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed.

Electroretinography (ERG) and genetic screening were performed in the 2 adults; fundus photographs, RPE autofluorescence, and Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) were reviewed.

Genetic Analyses

One patient was screened for the TEAD1 mutation. DNA was extracted from blood with the QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi Kit 51194 (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). Extracted genomic DNA was amplified for sequencing by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).14 The primers used for PCR flanked exon 12 and amplified a 361-base pair fragment (forward 5′-AGGACACAGAGTGAGGCTGA and reverse 5′-AAACCTCACCACACAGGGTG). The fragment was purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit 28106 (Qiagen Inc.) and sequenced by Genewiz (South Plainfield, NJ).

Autofluorescence Imaging

Autofluorescence images were obtained using a confocal scanning-laser ophthalmoscope (Heidelberg Retina Angiograph 2, Heidelberg Engineering, Dossenheim, Germany) by illuminating the fundus with argon laser light (488 nm) and viewing the resultant fluorescence through a bandpass filter with a short wavelength cutoff at 495 nm.15–18

Optical Coherence Tomography

Spectral domain OCT images were obtained using the Cirrus Spectral Domain OCT from Zeiss (Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc., Dublin, CA). The acquisition protocols included 5-line raster scans. Three scans were performed on each eye, and the one with the best signal strength was selected for the final analysis.

Electrophysiologic Testing

All subjects were tested using the Diagnosys Espion Electrophysiology System (Diagnosys LLC, Littleton, MA). For all recordings, the pupils were maximally dilated before full-field ERG testing using tropicamide (1%) and phenylephrine hydrochloride (2.5%); the corneas were anesthetized with a drop of 0.5% proparacaine. Silver-impregnated fiber electrodes (DTL; Diagnosys LLC) were used. Full-field ERGs to test generalized retinal function were performed using extended testing protocols incorporating the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV) standards. The minimum protocol incorporates the rod-specific and standard bright flash ERGs, both recorded after a minimum of 20 minutes of dark adaptation. After 10 minutes of light adaptation, the photopic 30-Hz flicker cone and transient photopic cone ERGs were recorded. A stimulus of 0.6 log units greater than the ISCEV standard flash was also used to better demonstrate the a-wave, as suggested in the recent revision of the ISCEV standard for ERG.19

Isolation of Nuclear Extracts

Murine samples of RPE, retina, choroid, skeletal muscle, liver, and heart were collected from 196 C57BL/6J mice 4 to 8 weeks old. Human samples of RPE, retina, choroid, and extraocular skeletal muscle were obtained from 4 fresh human eyes from the eye bank (National Disease Research Interchange, Philadelphia, PA). Nuclear extracts were prepared using the Panomics nuclear extraction kit (Panomics, Inc., Fremont, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, frozen samples were rinsed with 1.5 ml of ice-cold buffer A for each 0.5 g of tissue. Samples were ground in a glass Potter-Elvehjem (size 19) homogenizer and centrifuged at 14,000g for 3 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant containing the cytosolic fraction was removed. Each pellet was incubated on ice for 2 hours in 150 μl of buffer B. Samples were centrifuged at 14,000g for 5 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatants, containing the nuclear fraction, were collected. Protein concentrations of the nuclear fractions were measured with the Lowry assay (DC protein assay, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Western Blot Analysis

Nuclear extracts normalized for protein content (50 μg) were resolved by sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 7.5% acrylamide/2.6% crosslinker gel as previously described.14,18,20–23 Proteins were transferred onto a 0.2-μm nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories) for 1 hour at 25 V cm–1 using the method of Towbin et al.24 Membranes were blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 100 mmol/L Tris (pH 7.4), and 0.5% Tween-20. Membranes were incubated with either one of the following primary antibodies, TEAD1 (dilution 1:250, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and FOXA1 (dilution 1:250, HNF-3b (P-19), Santa Cruz Biotechnology), at 4°C overnight. Membranes were washed in Tris-buffered saline Tween-20 (TBST) for 10 minutes and exposed to the appropriate secondary antibody (dilution 1:10,000, goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin [Ig]G, and dilution 1:15,000, donkey anti-goat, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, respectively) in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were washed for 2×10 minutes in TBST, and immunodetection was performed using an enhanced chemiluminescence method (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Enhanced chemiluminescence signals were captured on Chemiluminescence BioMax Light Film (Kodak, Rochester, NY) and developed with a Konica Medical Film Processor SRX-101A (Konica Minolta Graphic Imaging USA, Inc., Glen Cove, NY).

Immunohistochemistry

Eyes from 4- to 8-week-old MF1 and C57BL/6J mice were enucleated and frozen immediately in optimum cutting temperature compound (Tissue-Tek OCT, Miles Laboratories, Elkhart, IN). Frozen eyes were sectioned using a cryostat set at 10 μm slice thickness. The sections were fixed in ice-cold methanol for 15 minutes at room temperature. A solution of 0.3% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline was used to permeabilize the membranes (10 minutes). Blocking was done with 1% bovine serum albumin and 10% goat serum in phosphate-buffered saline (blocking solution) for 30 minutes at room temperature. The sections were then incubated with the primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution at 4°C overnight. The samples were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with the secondary antibodies diluted in blocking solution. The sections were washed 3 times after each step in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes. The primary antibody used was TEAD1 (dilution 1:250, BD Biosciences). The secondary antibody used was Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-mouse IgG (dilutions 1:1000, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Results

Genetic Studies

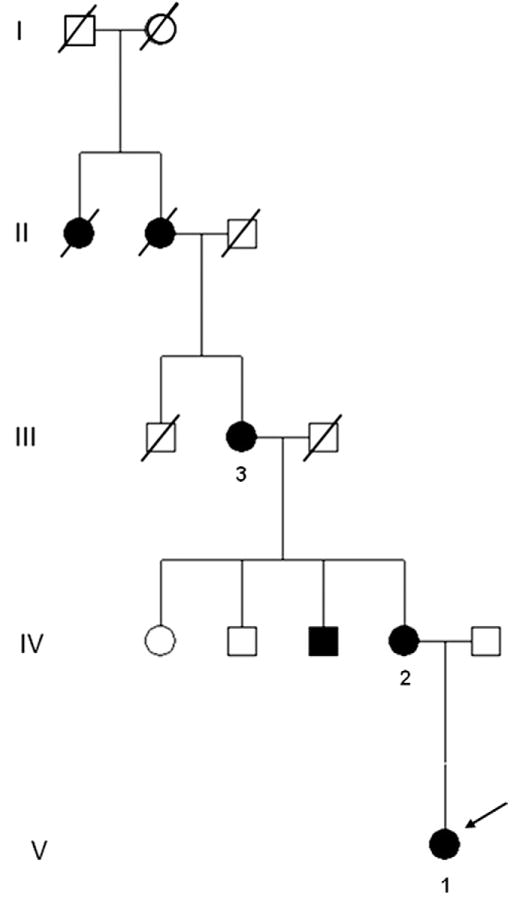

The 4-generation pedigree tree of the 3 tested individuals is shown in Figure 1. The history of eye disease may be traced back in the proband’s family to the great-grandmother and her mother. To support the clinical diagnosis of circumpapillary dysgenesis of the pigment epithelium, we genotyped the proband’s mother. A point mutation at T1261 in TEAD1 was detected in the mother, where the thymine base is mutated to a cytosine base (T1261C point mutation; data not shown). The proband’s mother and her grandmother were also evaluated.

Figure 1.

Four-generation pedigree of a family with circumpapillary dysgenesis of the pigment epithelium. Numbers 1, 2, and 3 indicate patient cases 1, 2, and 3. Arrow shows the proband (case 1).

Clinical Examination

Case 1

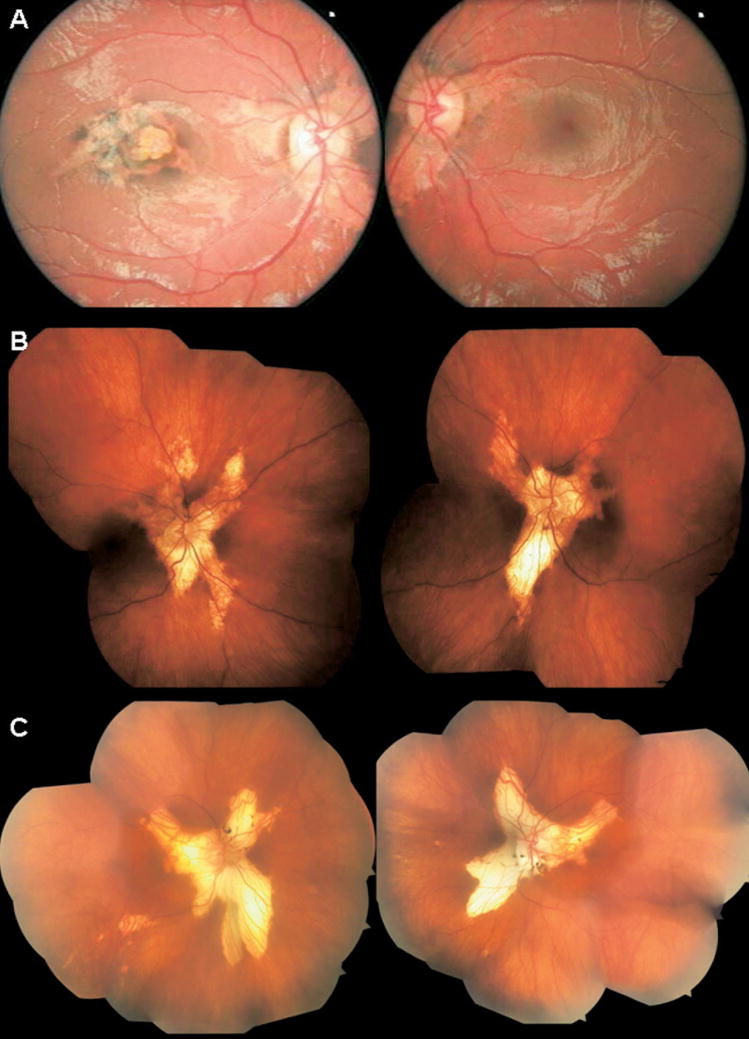

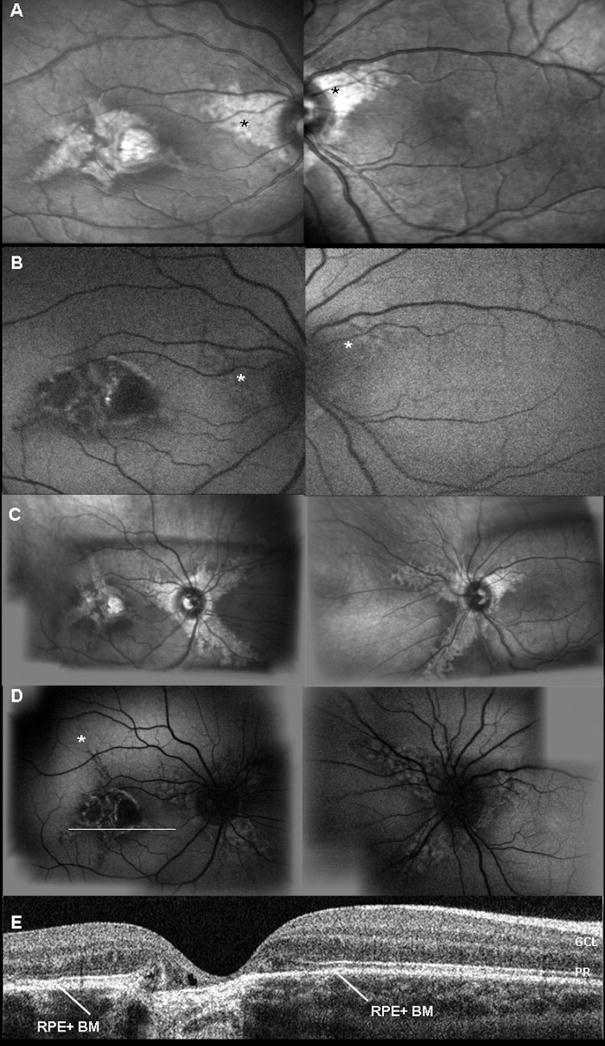

The proband, a 3-year-old girl, had no significant history of systemic disease or medication. Serum toxoplasma-specific IgG and IgM antibodies were not detected. She was able to read 20/70+1 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye without any spherical correction. Cycloplegic refraction was +1.50 sphere and −1.25 cylinder ×650 in the right eye and +1.87 sphere and −0.87 cylinder ×930 in the left eye. There were no signs of either strabismus or nystagmus. The anterior segment examination appeared to be quiet and without cataract. On dilated fundus examination, the patient showed symmetric, wing-shaped chorioretinal atrophy lesions radiating from the optic discs to the peripheral retina in both eyes (Fig 2A). In addition, she had a macular scar in the right eye. Infrared imaging highlighted the loss of choroidal structure (Fig 3A). On autofluorescent examination with the scanning–laser ophthalmoscope (HRA2), the RPE appeared to be intact around the peripapillary region in both eyes (Fig 3B). Retinal pigment epithelium autofluorescence was absent along the edge of the central chorioretinal scar (Fig 3B). After a 3-year follow-up period, an increase in choroidal depigmentation (Fig 3C) and a secondary increase in RPE autofluorescence were observed (Fig 3D). OCT scanning showed an intact RPE-Bruch’s membrane complex despite choroidal depigmentation in the macular region (Fig 3D and E). The ERG is within normal limit (not shown).

Figure 2.

Color fundus photographs of 3 cases. A, Color fundus photographs of the right (left) and left (right) eyes of case 1 show bilateral, finger-like projections of atrophy radiating from the optic disc. Note the atypical presentation of macular scarring with tongue-like projections of atrophy and areas of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) changes in the right eye. B, Composite color fundus photographs of case 2 show bilateral and symmetric finger-like projections of atrophic retina and choroid, extending from the optic nerve into the peripheral ocular fundus. C, Color fundus photographs of case 3 show the characteristic bilateral, well-defined, tongue-shaped strips of atrophic retina and choroid, radiating from the optic nerve into the periphery.

Figure 3.

Imagings of case 1. A, Infrared fundus imaging shows bilateral peripapillary areas of choroidal depigmentation. B, Fundus autofluorescence imaging of RPE; asterisk (*) indicates loss of choroidal architecture underneath a normal RPE layer. C, Progression of the tongue-like lesions affecting the choroid at 3 years’ follow-up. D, Fundus autofluorescence imaging of RPE at 3 years’ follow-up shows peripapillary atrophy and RPE mottling, which corresponds with underlying diseased choroid; asterisk (*) indicates progressive loss of choroid. E, Horizontal OCT scan through the macula shows atrophy of RPE– choriocapillaris complex and thinning of Bruch’s membrane. White line (in D, right eye) indicates where the OCT section was taken. RPE + BM = retinal pigment epithelium and Bruch’s membrane complex; PR = photoreceptor; GCL = ganglion cell layer.

Case 2

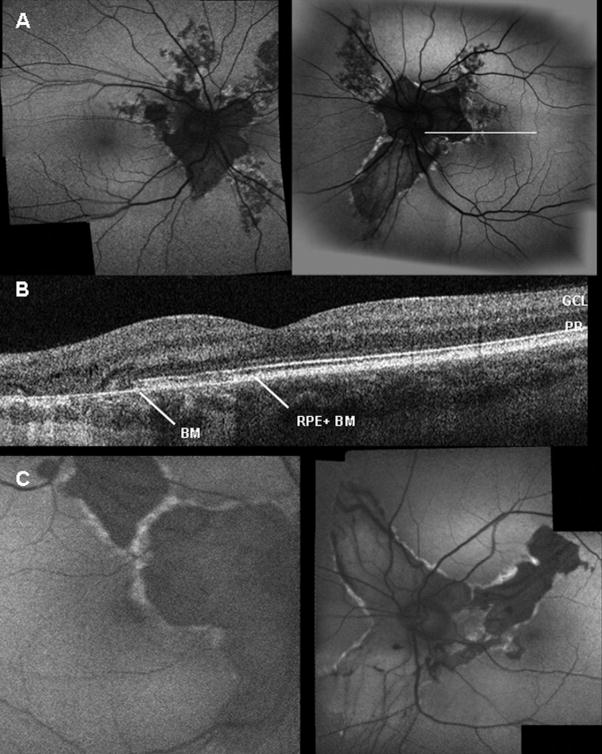

Examination of the 38-year-old mother showed that her uncorrected visual acuity in the right eye was 20/25+2 and 20/20 in the left eye. The anterior segment examination was unremarkable in both eyes and without anterior polar cataracts. Dilated funduscopic examination showed the characteristic chorioretinal atrophy lesions radiating from the optic discs. The peripapillary choroidal-retinal atrophy was symmetric in both eyes (Fig 2B). There were no signs of macular edema. Scanning laser ophthalmoscope examination showed the autofluorescent pattern was consistent with RPE and choroidal atrophy along the peripapillary region in both eyes. Autofluorescent hyperdensity was seen along the edge of the chorioretinal degeneration secondary to the RPE atrophy (Fig 4A). OCT examination showed only a remaining thin layer of Bruch’s membrane after RPE loss (Fig 4B). Larger choroidal vessels were visible through this area devoid of RPE cells. The ERG is within normal limit (not shown).

Figure 4.

Imaging of cases 2 and 3. A, Fundus autofluorescence imaging of case 2 reveals typical lesions with central hypofluorescence and well-delineated hyperfluorescent margins. Increased visualization of choroidal vessels is seen in regions devoid of RPE. B, OCT shows thinning of RPE–Bruch’s membrane choriocapillaris complex. White line (in A, left eye) indicates where OCT section was taken. C, Autofluorescence imaging of case 3 shows typical lesions, with visible larger choroidal vessels through the atrophic RPE. RPE + BM = retinal pigment epithelium and Bruch’s membrane complex; BM = Bruch’s membrane; GCL = ganglion cell layer; PR = photoreceptor.

Case 3

Examination of the 68-year-old grandmother showed that her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/25+2 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. The anterior segment examination appeared to be quiet and with mild nuclear sclerotic cataracts. A dilated fundus examination revealed typical, symmetric helicoidal peripapillary chorioretinal atrophy lesions in both eyes (Fig 2C). There was no evidence of macular edema. Scanning laser ophthalmoscope examination showed that the autofluorescent pattern was consistent with RPE and choroidal atrophy along the peripapillary region in both eyes. Significant hyperfluorescence was seen along the edge of the chorioretinal degeneration secondary to the RPE atrophy (Fig 4C). The ERG is within normal limit (not shown).

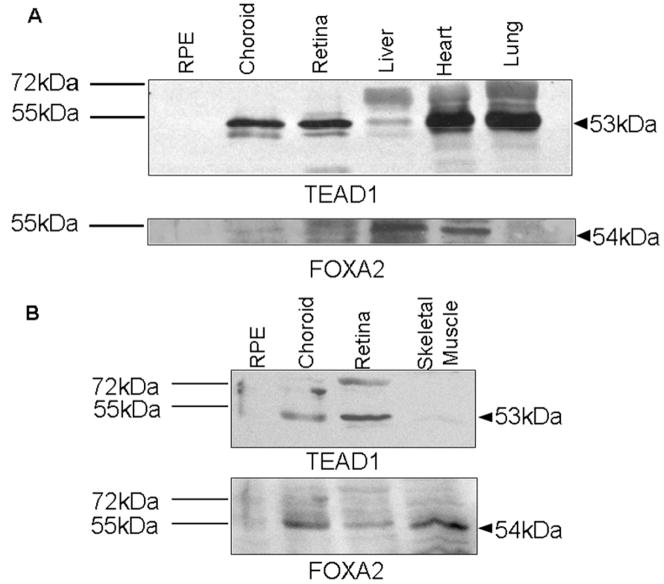

Expression of TEAD1, FOXA2, and YAP65 in Various Tissue Samples

Western blot analysis of murine tissues revealed the presence of a 53-kDa protein in the neuroretinal and choroidal samples. The positive controls of heart and lung samples confirmed the detection of the TEAD1 protein at the correct molecular weight (Fig 5A). By densitometry analysis, we observed an identical signal for TEAD1 in the choroid (101.5%) compared with the neuroretina (100%), whereas there was an absence of signal in the RPE sample. Analysis of FOXA2 expression showed similar patterns, with a distinct band for the FOXA2 protein at 54 kDa in the neuroretina and choroid. The level of FOXA2 in the choroid was 91.6% of the level in the neuroretinal sample (Fig 5A). The expression patterns of TEAD1 and FOXA2 in the human tissues of neuroretina, choroid, and RPE correlated with the murine results. The human choroid and neuroretina showed a distinct band at 53 kDa corresponding to the TEAD1 protein (Fig 5B). Densitometry analysis revealed that the level of TEAD1 in the human choroid was 86.7% of that in the neuroretina. A faint band in the human RPE sample could be seen. The FOXA2 levels for the human neuroretina and choroid sample were identical (100% and 106.3%, respectively; Fig 5B). YAP65 expression was detected in all examined tissues (data not shown).

Figure 5.

TEAD1 and FOXA2 expression in murine and human eye tissue. Samples were loaded equally with 50 μg total protein content. A, Murine heart and lung were used as positive controls; murine liver was used as negative control for TEAD1. Murine liver is a positive control for FOXA2, whereas lung is a negative control. B, Human skeletal muscle was used as positive control for FOXA2. The corresponding molecular weight of TEAD1 and FOXA2 is indicated with an arrow; the protein standard ladder is given on the left.

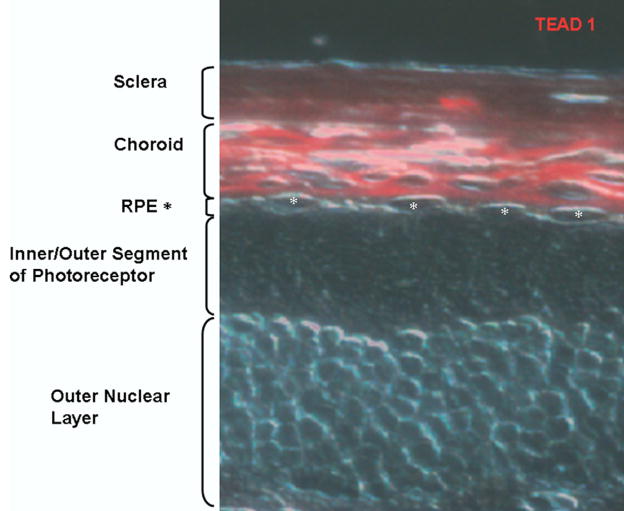

Immunohistochemistry

The result of the immunohistochemistry on frozen sections of mouse retina corresponds with the western blot analysis of murine tissue (Fig 6). The TEAD1 protein is clearly detectable within the choroid, giving a strong red fluorescence signal. The RPE layer is devoid of any signal. On the basis of these findings, it can be concluded that TEAD1 is not detected in RPE but is found abundantly in the choroid.

Figure 6.

Localization of TEAD1 in choroid. Immunohistochemistry of frozen mouse retinal sections using antibodies against TEAD1 (red). RPE = retinal pigment epithelium (*).

Discussion

Choroidal dysfunction contributes to the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration (AMD).25–28 Twenty percent of Caucasians will develop some form of AMD between 65 and 75 years of age. Preserving choroidal function will therefore have a tremendous impact on the quality of life of many patients. Understanding the TEAD1-FOXA2 interaction is crucial for developing better treatment modalities for choroidal diseases, including AMD and circumpapillary dysgenesis of the pigment epithelium.

Lesions generally begin in the peripapillary area during the first year of life, but the macula will be the eventual site of involvement that leads to blindness. The 3-year-old proband, her mother, and her grandmother showed typical evidence of circumpapillary dysgenesis of the pigment epithelium with wide tongue-shaped extensions to the periphery without connection to the retinal vessels. The genetic sequencing of DNA substantiated the diagnosis through the discovery of the T1261C point mutation. The relatively normal electrophysiologic finding is consistent with previous reports in the literature. The progressive macular degeneration in the right eye of the proband has autofluorescent features similar to her peripapillary region. Therefore, it is likely that her macular atrophic scar is a new variant of this particular condition.

On the basis of reverse transcriptase-PCR assays, the defective gene product TEAD1 is expressed in the human retina,29 but the cellular origin of circumpapillary dysgenesis of the pigment epithelium1 is controversial.30 The RPE has been suggested as the site of the primary defect.30,31 Our clinical imaging studies on circumpapillary dysgenesis of the pigment epithelium (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 108985) revealed the choroid as the primary site of onset of the disease.

The presence of preserved RPE in our 3-year-old proband on autofluorescence imaging and Fourier-domain OCT is consistent with our hypothesis that the RPE does not primarily contribute to the initial stages of circumpapillary dysgenesis of the pigment epithelium. The overlying RPE remained relatively intact through this area of progressive choroidal degeneration in a 3-year follow-up period. Our OCT studies also provided the first evidence that the hyper-reflective band within the outermost outer retina consists of the RPE-Bruch’s membrane complex. A thin hyper-reflective band is seen in areas lacking RPE.

Early choroidal depigmentation, revealed by infrared imaging, suggests that the disease originates in the choroid. Later on in the course of the disorder, diseased RPE shows high-density fluorescent lesions, consistent with localized abnormal accumulation of the fluorophore. TEAD1 is also expressed in the neuroretina, but the relatively intact ERGs in our patients suggested the Y421H mutation of TEAD1 does not compromise (outer) retinal function.32

Our biochemical and immunohistochemical data revealed the significance of the TEAD1-FOXA2 interaction in the maintenance of the choroid. The immunoblot studies of murine and human samples confirmed TEAD1 expression in the retina and choroid. In the mouse RPE, TEAD1 is not detectable at all, whereas the human RPE showed a faint band at the expected molecular weight. This discrepancy may be explained by the method of collecting the RPE. The scraping of RPE cells from both the retina and choroid results in a trace contamination of the RPE sample. Until now, there has been no other known isolation method for the RPE.

TEAD1 is required for FOXA2 expression. This is supported by the absence of FOXA2 in both murine and human RPE. The T1261C point mutation in Icelandic families is located at a conserved binding site in TEAD1 for its cofactor YAP65. TEAD1 and YAP65 interact in the nucleus, where YAP65 activates the RNA polymerase II complex and TEAD1 binds to the FOXA2 enhancer, thereby regulating FOXA2 transcription. FOXA2 governs transthyretin and other choroidal gene expression.

The primary cellular origin of circumpapillary dysgenesis of the pigment epithelium is within the choroid instead of the pigment epithelium. The loss of the RPE and photoreceptors in later stages of the disease is a secondary consequence of choroidal degeneration. Future studies of the TEAD1-FOXA2 signaling cascade in the choroid should identify pharmacologic targets to treat circumpapillary dysgenesis of the pigment epithelium and other associated macular diseases.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

SHT is a Burroughs Wellcome Program in Biomedical Sciences Fellow and is also supported by the Charles E. Culpeper Scholarship, Foundation Fighting Blindness, Hirschl Trust, Crowley Research Fund, Schneeweiss Stem Cell Fund, Hoffman Scholarship fund, gift of Joel S. Hoffmann, Jonas Family Fund, Hartford/American Geriatrics Society, Eye Surgery Fund, Bernard Becker-Association of University Professors in Ophthalmology-Research to Prevent Blindness, and R01EY018213. NKW is supported by the National Science Council NSC-096–2917-I-002–105 and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital Fellowship CMRPG360571.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure(s):The author(s) have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Rubino A. Su una particolare anomalia bilaterale e simmetrica dello strato pigmento retinico. Boll Ocul. 1940;19:318–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franceschetti A. A curious affection of the fundus oculi: helicoid peripapillar chorioretinal degeneration—its relation to pigmentary paravenous chorioretinal degeneration. Doc Ophthalmol. 1962;16:81–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00146721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sveinsson K. Helicoidal peripapillary chorioretinal degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1979;57:69–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1979.tb06661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sveinsson K. Choroiditis areata. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1939;17:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fossdal R, Jonasson F, Kristjansdottir GT, et al. A novel TEAD1 mutation is the causative allele in Sveinsson’s chorioretinal atrophy (helicoid peripapillary chorioretinal degeneration) Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:975–81. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jonasson F, Sander B, Eysteinsson T, et al. Sveinsson chorioretinal atrophy: the mildest changes are located in the photoreceptor outer segment/retinal pigment epithelium junction. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85:862–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jonasson F, Hardarson S, Olafsson BM, Klintworth GK. Sveinsson chorioretinal atrophy/helicoid peripapillary chorioretinal degeneration: first histopathology report. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1541–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morin-Kensicki EM, Boone BN, Howell M, et al. Defects in yolk sac vasculogenesis, chorioallantoic fusion, and embryonic axis elongation in mice with targeted disruption of Yap65. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:77–87. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.77-87.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitagawa M. A Sveinsson’s chorioretinal atrophy-associated missense mutation in mouse TEAD1 affects its interaction with the co-factors YAP and TAZ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361:1022–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sudol M, Bork P, Einbond A, et al. Characterization of the mammalian YAP (Yes-associated protein) gene and its role in defining a novel protein module, the WW domain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14733–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramalho-Santos M, Yoon S, Matsuzaki Y, et al. “Stemness”: transcriptional profiling of embryonic and adult stem cells. Science. 2002;298:597–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1072530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sawada A, Nishizaki Y, Sato H, et al. TEAD proteins activate the Foxa2 enhancer in the node in cooperation with a second factor. Development. 2005;132:4719–29. doi: 10.1242/dev.02059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes DE, Stolz DB, Yu S, et al. Elevated hepatocyte levels of the Forkhead box A2 (HNF-3beta) transcription factor cause postnatal steatosis and mitochondrial damage. Hepatology. 2003;37:1414–24. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsang SH, Woodruff ML, Jun L, et al. Transgenic mice carrying the H258N mutation in the gene encoding the beta-subunit of phosphodiesterase-6 (PDE6B) provide a model for human congenital stationary night blindness. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:243–54. doi: 10.1002/humu.20425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Ruckmann A, Fitzke FW, Bird AC. Distribution of fundus autofluorescence with a scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:407–12. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.5.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robson AG, Egan C, Holder GE, et al. Comparing rod and cone function with fundus autofluorescence images in retinitis pigmentosa. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;533:41–7. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0067-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robson AG, Saihan Z, Jenkins SA, et al. Functional characterisation and serial imaging of abnormal fundus autofluorescence in patients with retinitis pigmentosa and normal visual acuity. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:472–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.082487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsang SH, Vaclavik V, Bird AC, et al. Novel phenotypic and genotypic findings in X-linked retinoschisis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:259–67. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marmor MF, Holder GE, Seeliger MW, Yamamoto S. Standard for clinical electroretinography (2004 update) Doc Ophthalmol. 2004;108:107–14. doi: 10.1023/b:doop.0000036793.44912.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsang SH, Gouras P, Yamashita CK, et al. Retinal degeneration in mice lacking the gamma subunit of rod cGMP phosphodiesterase. Science. 1996;272:1026–9. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsang SH, Burns ME, Calvert PD, et al. Role of the target enzyme in deactivation of photoreceptor G protein in vivo. Science. 1998;282:117–21. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsang SH, Woodruff ML, Chen CK, et al. GAP-independent termination of photoreceptor light response by excess gamma subunit of the cGMP-phosphodiesterase. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4472–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4775-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsang SH, Woodruff ML, Janisch KM, et al. Removal of phosphorylation sites of gamma subunit of phosphodiesterase 6 alters rod light response. J Physiol. 2007;579:303–12. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.121772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:4350–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piguet B, Palmvang IB, Chisholm IH, et al. Evolution of age-related macular degeneration with choroidal perfusion abnormality. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;113:657–63. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74790-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pauleikhoff D, Spital G, Radermacher M, et al. A fluorescein and indocyanine green angiographic study of choriocapillaris in age-related macular disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1353–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.10.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciulla TA, Harris A, Kagemann L, et al. Choroidal perfusion perturbations in non-neovascular age related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:209–13. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rechtman E, Harris A, Siesky B, et al. The relationship between retrobulbar and choroidal hemodynamics in non-neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2007;38:219–25. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20070501-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vassilev A, Kaneko KJ, Shu H, et al. TEAD/TEF transcription factors utilize the activation domain of YAP65, a Src/Yes-associated protein localized in the cytoplasm. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1229–41. doi: 10.1101/gad.888601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brazitikos PD, Safran AB. Helicoid peripapillary chorioretinal degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;109:290–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magnusson L. Atrophia areata: a variant of peripapillary chorioretinal degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1981;59:659–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1981.tb08731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eysteinsson T, Jonasson F, Jonsson V, Bird AC. Helicoidal peripapillary chorioretinal degeneration: electrophysiology and psychophysics in 17 patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:280–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.3.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]