Abstract

Objectives To compare the effectiveness of punch biopsy and selective recall for treatment versus a policy of immediate treatment by large loop excision in the management of women with low grade abnormal cervical cytology referred for colposcopy.

Design Multicentre individually randomised controlled trial, nested within the NHS cervical screening programmes.

Setting Grampian, Tayside, and Nottingham.

Participants 1983 women, aged 20-59, with cytology showing borderline nuclear abnormalities or mild dyskaryosis, October 1999-October 2002.

Interventions Immediate large loop excision or up to four targeted punch biopsies taken immediately with recall for treatment (by large loop excision) if these showed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or III or worse. Participants were followed for three years, concluding with an exit colposcopy.

Main outcome measures Clinical end points: cumulative incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse and grade III or worse at three years. Clinically significant anxiety and depression and self reported after effects assessed six weeks after colposcopy, biopsies, or large loop excision.

Results 879 women (44%) had a normal transformation zone at colposcopy and had no further procedures at that time. Colposcopists were less likely to classify the transformation zone as abnormal when the allocation was large loop excision (603 (60%) in the biopsy and selective recall group; 501 (51%) in the immediate large loop excision group). Of women randomised to biopsy and recall, 157 (16%) required a second clinic visit for treatment. Specimens from almost 60% (n=296) of women who underwent immediate large loop excision showed no cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (31%; n=156) or showed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade I (28%; n=140). The percentages of women diagnosed with grade II or worse up to and including the exit examination were 22% (n=216) in the biopsy and recall arm and 23% (n=228) in the immediate large loop excision arm. There was no significant difference between the arms in cumulative incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse (adjusted relative for risk large loop excision v biopsy 1.04, 95% confidence interval 0.86 to 1.25) or grade III or worse (1.03, 0.79 to 1.34). A greater proportion of disease was detected at initial investigation and less during follow-up and at exit in the immediate large loop excision arm, but time of detection did not differ significantly between arms. Levels of anxiety and depression and reported pain did not differ between arms. Higher proportions of women randomised to large loop excision reported moderate or more severe bleeding and discharge.

Conclusion A policy of targeted punch biopsies with subsequent treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or III and cytological surveillance for grade I or less provides the best balance between benefits and harms for the management of women with low grade abnormal cytology referred for colposcopy. Immediate large loop excision results in overtreatment and more after effects and should not be recommended.

Trial Registration ISRCTN 34841617.

Introduction

Colposcopy has a central role in the diagnostic investigation and management of women with premalignant disease of the cervix detected by abnormal results on cervical cytology in NHS cervical screening programmes.1 2 In women with low grade abnormal cytology (see www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/cervical/) in recent years there has been a trend towards increasing referral for colposcopy, rather than surveillance by repeat cytology tests.3 This change in practice evolved from recognition that some women with low grade abnormal cytology have underlying high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia4 and might eventually require colposcopy for persistent cytological abnormalities.5

At colposcopy, if the cervical transformation zone is not normal, women can be managed by immediate removal of the entire transformation zone by large loop excision. This strategy—known as see-and-treat—has become increasingly common in NHS cervical screening programmes.6 It enables full histological examination, removes any cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, and, for most women, is adequate treatment.7 By avoiding the need for a return visit for treatment, it minimises non-attendance and potentially improves the efficiency of clinical services.8 9 10 Immediate large loop excision, however, also results in “overtreatment” (that is, treatment of women without histologically confirmed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia), the extent of which might be substantial,11 especially among those with low grade abnormal cytology. Overtreatment puts women at unnecessary risk of side effects such as bleeding and infection.11 As the procedure can also have adverse effects on subsequent reproductive function,12 a more conservative management approach might be preferable.

Punch biopsies of the most abnormal areas directed colposcopically, with recall for treatment (by excision or ablation) if histology confirms cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, offers a more conservative approach. This strategy, however, also has drawbacks,13 chiefly with regard to the reliability of punch biopsies in identifying prevalent high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.14 When only a fraction of the transformation zone is sampled, the ability of colposcopists to identify abnormality and target accurately is limited and biased to the most accessible areas.15 16 Small lesions, microinvasive disease, and glandular intraepithelial neoplasia might be missed (“under calling”).17 Moreover, high grade disease might subsequently develop in women with histologically confirmed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade I who are not treated.18

No randomised controlled trials have evaluated immediate large loop excision compared with biopsy and selective recall in women with low grade abnormal cytology. Most evidence relates to histological findings from punch biopsies and large loop excisions in the same women.17 19 20 21 Two small cross sectional studies comparing women managed by biopsy and selective recall with those managed by immediate large loop excision found no differences in histological outcomes,22 23 while one study of women with high grade abnormal cytology suggested immediate large loop excision was associated with lower levels of anxiety after the intervention and higher levels of relief.24

There is a complex interplay between adequately diagnosing and effectively treating the individual woman at colposcopy, while avoiding unnecessary interventions and providing an efficient clinical service. For the NHS cervical screening programmes this translates into balancing benefits and harms, while keeping health service costs at a reasonable level.25 We report results from the trial of management of borderline and other low grade abnormal smears (TOMBOLA) on the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, and psychosocial and physical after effects associated with immediate large loop excision versus biopsy and selective recall for treatment. Cost effectiveness is reported in a companion paper.26

Methods

The trial involved two randomisations, the first to cytological surveillance or initial colposcopy and the second, within the women assigned to colposcopy, to biopsy and selective recall or immediate large loop excision. Results of the first randomisation are reported in a companion paper.27

Participants and recruitment

Details of eligibility and recruitment, informed consent, and ethical approval are described elsewhere.27 28 Briefly, all participants had been called for a routine cytology test as part of the NHS cervical screening programmes and attended for that test in October 1999-October 2002. Eligible women were aged 20-59, had mild dyskaryosis or borderline nuclear abnormalities, were not pregnant, and had not had previous destructive or excisional treatment.

Procedures and follow-up

At the colposcopy appointment, consenting women were immediately randomised to biopsy and selective recall or immediate large loop excision with a telephone service provided by the health service research unit of Aberdeen University. Randomisation was stratified by centre, age group, cytology grade, and high risk human papillomavirus status at recruitment. Women then underwent colposcopy. Colposcopists were not blinded to the randomisation. Colposcopic examination and description of findings followed standard practice.29 We included women who had an adequate colposcopic examination (the whole of the transformation zone and any lesions were viewed in their entirety); those with inadequate colposcopy were treated according to local NHS protocols. Of women with adequate colposcopy, those with an abnormal transformation zone (colposcopic lesion with acetowhitening with or without capillary vessel patterns) received the intervention assigned by randomisation while those whose transformation zone did not fulfil the definition of abnormal (henceforth “normal” transformation zone) were followed-up in general practice with cytology tests every 12 months.

For biopsy and selective recall, up to four targeted punch biopsies were taken from the most abnormal areas. Women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or III (II/III) on histology were recalled for treatment with large loop excision. Women with no cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or grade I disease on histology did not receive any further treatment at that time and were followed-up in general practice with cytology tests every six months. In the other arm, the whole transformation zone, including the abnormality, was treated immediately by large loop excision. In both arms women with histology worse than grade III were treated and subsequently followed-up according to standard practice. Follow-up after punch biopsies or large loop excision was with cytology tests every six months in general practice. For all women, cytology follow-up results were monitored with subsequent action (next recommended test date or colposcopy referral) based on these. If women were referred for colposcopy during follow-up, they attended local colposcopy clinics and were treated, if required, according to local NHS protocols.

About three years after recruitment, women were invited for an exit colposcopy examination, with large loop excision if the transformation zone appeared abnormal; this examination was for the purposes of the trial and was over and above standard practice in the NHS cervical screening programmes. Clinicians were blinded to women’s cytology results and high risk human papillomavirus status at recruitment, their randomisation arm(s), and clinical outcomes (cytology and histology) since recruitment. Participants’ medical records and hospital and pathology databases were reviewed to ascertain any additional procedures (cytology, colposcopy, histology, treatment, or admission to hospital) during follow-up.

Colposcopy, cytology, and histology quality assurance

Colposcopists were accredited by the British Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Cytopathology and histopathology laboratories participated in national quality assurance schemes. For quality assurance purposes, one or two independent pathologists who were not aware of the original histopathological results centrally reviewed large loop excision and punch biopsy samples from a random sample of 272 participants. In 252 cases the review diagnosis was identical to the original diagnosis (κ=0.9). Further details of quality assurance exercises are reported elsewhere.27 28

Sociodemographic information

At recruitment women completed a sociodemographic questionnaire.28

Clinical outcomes

The main clinical outcome was established a priori as the cumulative incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or more severe disease from recruitment up to and including the exit examination as this is the histological threshold at which women are usually treated in the NHS cervical screening programmes. We also considered the subsidiary outcome of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III or more severe disease. Each woman was counted only once as a “case”—at the date of the first occurrence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse—and was classified according to the highest grade of histology reported, whether on punch biopsy or large loop excision. Women with a normal transformation zone at initial colposcopy were assumed to have no cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at that time.

Psychosocial and physical morbidity

Psychosocial sequelae were assessed throughout follow-up and will be reported in detail elsewhere. A subgroup of women was invited to complete the hospital anxiety and depression scale30 six weeks after colposcopy and related interventions. This subgroup comprised all women recruited from February 2001 onwards in the colposcopy arm of the trial who consented to randomisation at the colposcopy appointment (n=989). These women were also asked, by means of a postal questionnaire administered together with the six week psychosocial assessment, to provide information on any physical after effects (pain, bleeding, and discharge) they had experienced. In addition, clinic staff recorded complications occurring during colposcopy, biopsies, and large loop excision.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were by intention to treat. To accommodate variability between participants in length of follow-up, each woman accrued person years from the randomisation date until the date of the exit appointment for those who attended and, for others, the date the exit appointment was scheduled or the date they requested to leave the trial, had a hysterectomy, died, or moved from the area. We compared the cumulative incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse for immediate large loop excision versus biopsy and selective recall using relative risks, computed by Poisson regression. Risk estimates were adjusted only for the randomisation stratification variables; adjustment for a range of other sociodemographic and lifestyle factors had little effect. To investigate heterogeneity in detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia by the management policies, we repeated analyses stratifying by age at recruitment (20-29, 30-59), recruitment cytology (mild dyskaryosis, borderline nuclear abnormalities), and whether women had had previous cytology showing borderline nuclear abnormalities. Kaplan-Meier curves examined the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse over time, with arms compared by the log rank test. All analyses were repeated for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III or worse. We computed two estimates of overtreatment by a policy of immediate large loop excision11 based on outcomes after initial colposcopy and large loop excision (that is, without follow-up). Firstly, we used the National Cancer Institute definition: percentage of specimens found to have no cervical intraepithelial neoplasia/grade I disease,31 and, secondly, we used the NHS cervical screening programme definition: percentage of specimens found to have no cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.2 We used z tests to compare the proportions of women who scored ≥11 on the anxiety subscale and ≥8 on the depression subscale of the hospital anxiety and depression scale and who reported pain, bleeding, and discharge (any, and that rated as moderate or more severe) at six weeks after the last procedure (whether colposcopy, punch biopsies, or large loop excision). Wilcoxon tests compared reported durations of pain, bleeding, and discharge.

Statistical power

We estimated that about 2130 women would give 86% power to detect a relative risk of 1.25 in the cumulative incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse, assuming overall cumulative incidence of 15% (α=0.05, two sided test).

Results

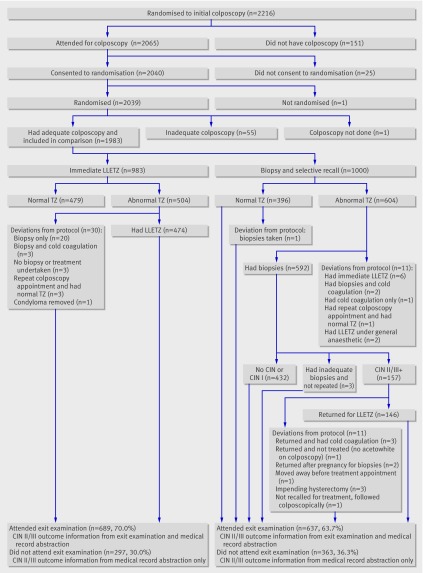

Figure 1 summarises numbers of women recruited, randomised, and followed-up. Of the 2065 women who attended for colposcopy, 2039 consented and were randomised. One woman did not have a colposcopy and 55 (2.7%) had an inadequate colposcopy and were excluded; 1000 were randomised to biopsy and selective recall and 983 to immediate large loop excision. At the exit examination 689 (70.0%) women in the immediate large loop excision arm and 637 (63.7%) in the other arm attended.

Fig 1 Numbers of women randomised and followed up and deviations from protocol (LLETZ=large loop excision of transformation zone; TZ=transformation zone, CIN=cervical intraepithelial neoplasia)

Characteristics of participants

The trial arms were balanced in terms of the stratification variables at randomisation and other sociodemographic and lifestyle factors (table 1). In each arm around 43% were aged 20-29 and 57% aged 30-59. Slightly over a third had mild dyskaryosis at recruitment; of these, 8% had had previous cytology showing borderline nuclear abnormalities. Almost a quarter of those with borderline nuclear abnormalities at recruitment had had a previous smear with the same result. Most women were white and in full or part time employment, and almost 20% had obtained a college or university degree.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women at recruitment, by trial arm. Figures are numbers (percentages) of women

| Biopsy and recall | Immediate large loop excision | |

|---|---|---|

| Total women randomised | 1000 (100) | 983 (100) |

| Cytological status at recruitment: | ||

| Mild dyskaryosis, with previous borderline nuclear abnormalities | 32 (3) | 26 (3) |

| Mild dyskaryosis, no previous borderline nuclear abnormalities | 328 (33) | 318 (32) |

| Borderline nuclear abnormalities, with previous borderline nuclear abnormalities | 147 (15) | 141 (14) |

| Borderline nuclear abnormalities, no previous borderline nuclear abnormalities | 493 (49) | 498 (51) |

| Age (years): | ||

| 20-29 | 433 (43) | 426 (43) |

| 30-39 | 273 (27) | 273 (28) |

| 40-49 | 213 (21) | 203 (21) |

| 50-59 | 81 (8) | 81 (8) |

| Human papillomavirus status*: | ||

| High risk | 397 (40) | 385 (39) |

| Not high risk | 522 (52) | 514 (52) |

| Not known† | 81 (8) | 84 (9) |

| Trial centre: | ||

| A | 336 (34) | 326 (33) |

| B | 231 (23) | 229 (23) |

| C | 433 (43) | 428 (44) |

| Deprivation category‡: | ||

| 1 (least deprived) | 130 (13) | 125 (13) |

| 2 | 191 (19) | 175 (18) |

| 3 | 164 (16) | 178 (18) |

| 4 | 261 (26) | 273 (28) |

| 5 (most deprived) | 254 (25) | 232 (24) |

| Ethnic group: | ||

| White | 953 (95) | 936 (95) |

| Other§ | 42 (4) | 38 (4) |

| Not stated | 5 (1) | 9 (1) |

| Education/training after school: | ||

| None | 261 (26) | 257 (26) |

| Through work with formal qualifications | 184 (18) | 182 (19) |

| Qualification other than degree from college/university | 267 (27) | 259 (26) |

| University/college degree | 173 (17) | 203 (21) |

| Current student | 111 (11) | 77 (8) |

| Not stated | 4 (0) | 5 (1) |

| Employment status: | ||

| Full time paid employment | 482 (48) | 507 (52) |

| Part time paid employment | 244 (24) | 217 (22) |

| Student | 111 (11) | 77 (8) |

| Not in paid employment | 160 (16) | 179 (18) |

| Not stated | 3 (0) | 3 (0) |

| Marital status: | ||

| Married/living as married | 547 (55) | 520 (53) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 136 (14) | 136 (14) |

| Single | 309 (31) | 316 (32) |

| Not stated | 8 (1) | 11 (1) |

| Ever been pregnant: | ||

| Yes | 685 (69) | 649 (66) |

| No | 309 (31) | 329 (33) |

| Not stated | 6 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Parity: | ||

| 0 | 419 (42) | 436 (44) |

| 1 | 162 (16) | 144 (15) |

| ≥2 | 397 (40) | 386 (39) |

| Not stated | 22 (2) | 17 (2) |

| Current contraception: | ||

| Use of pill or other hormonal contraceptives only | 395 (40) | 328 (33) |

| Use of barrier contraceptive only | 133 (13) | 144 (15) |

| Use of hormonal and barrier contraceptives | 33 (3) | 34 (3) |

| None | 436 (44) | 474 (48) |

| Missing | 3 (0) | 3 (0) |

| Physical activity: | ||

| <1 time/week | 400 (40) | 396 (40) |

| 1-3 times/week | 225 (23) | 228 (23) |

| >3 times/week | 360 (36) | 346 (35) |

| Not stated | 15 (2) | 13 (1) |

| Smoking status: | ||

| Never smoked | 453 (45) | 467 (48) |

| Former smoker | 171 (17) | 160 (16) |

| Current smoker | 367 (37) | 348 (35) |

| Not stated | 9 (1) | 8 (1) |

*Based on polymerase chain reaction analysis with GP5+/6+ consensus primers, followed by enzyme immunoassay for detection of 14 “high risk” human papillomavirus types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68).

†Includes women whose samples were inadequate for analysis (n=14) and women who did not have human papillomavirus test at recruitment (n=151).

‡Carstairs deprivation measure based on population fifths assigned from address of residence at recruitment.

§Black-Caribbean n=29; Black-African n=4; Black-other n=8; Indian n=8; Pakistani n=10; Bangladeshi n=2; Chinese n=7; other ethnic group n=12.

Colposcopic impression and related histology: cross sectional results

Overall, 44% of women had a normal transformation zone at colposcopy and had no further procedures at that time. This percentage was higher in women who were older (53% in those aged 30-59 v 34% in those aged 20-29) or were recruited with cytology showing borderline nuclear abnormalities (52% v 30% of those with mild dyskaryosis).

In comparing the trial arms, the proportion judged to have an abnormal transformation zone was significantly lower in the immediate large loop excision arm (51%) than the biopsy and recall arm (60%, z=5.04, P<0.001; table 2). Fewer women in the immediate large loop excision arm had no cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (16% v 27%) and grade I disease on histology (14% v 17%) and the frequency of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse was slightly higher in this arm (21% v 16%). Three women had disease worse than cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III (one cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasia and two squamous carcinomas (FIGO stage IA1, FIGO stage IB)), two of whom were in the large loop excision arm.

Table 2.

Colposcopic impression and histological* outcome of initial colposcopy examination and related procedures, by trial arm (cross sectional analysis)

| Biopsy and recall | Immediate large loop excision | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (% of those in arm) | % of those with abnormal transformation zone | No (% of those in arm) | % of those with abnormal transformation zone | ||

| Total women randomised | 1000 (100) | — | 983 (100) | — | |

| Normal transformation zone†‡ | 397 (40) | — | 482 (49) | — | |

| Abnormal transformation zone§ | |||||

| Total | 603 (60) | 100 | 501 (51) | 100 | |

| No CIN | 269 (27) | 45 | 156 (16) | 31 | |

| CIN grade I | 168 (17) | 28 | 140 (14) | 28 | |

| CIN grade II or worse¶ | 160 (16) | 27 | 202 (21) | 40 | |

| CIN grade II | 77 | — | 100 | — | |

| CIN grade III or worse¶ | 83 | — | 102 | — | |

| Other** | 6 (0.6) | 1 | 3 (0.3) | 0.6 | |

CIN=cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

*Represents most severe histology recorded after initial colposcopy (that is, for women in whom biopsy and large loop excision results did not correspond, most severe has been recorded).

†No abnormal transformation zone on colposcopy; women did not have any further procedures at this time.

‡Biopsy and recall figure includes 396 women with normal transformation zone on initial colposcopy, plus one woman originally found to have abnormal transformation zone who returned for treatment and at repeat colposcopy had normal transformation zone; immediate large loop excision figure includes 479 women with normal transformation zone at initial colposcopy, plus three women with abnormal transformation zone who were not treated immediately and, at repeat colposcopy, were found to have normal transformation zone.

§Abnormal transformation zone at colposcopy and women went on to receive intervention assigned by randomisation.

¶Three women had disease worse than CIN III, one in biopsy and recall arm and two in immediate large loop excision arm.

**Includes three women with inadequate histology (biopsy and recall arm), and six with no histology (three in each arm).

Diagnostic yield of immediate large loop excision

In the immediate large loop excision arm, 474 of the 501 women with an abnormal transformation zone underwent large loop excision (fig 1). An average of 2.3 large loop excision procedures were undertaken per case of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse detected; 4.7 large loop excision procedures were done per case of grade III or worse.

Recall for treatment and default after punch biopsies

In 157 women punch biopsies indicated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse (fig 1), thus 16% of women randomised to biopsy and recall (and 26% with an abnormal transformation zone in that arm) potentially needed to return to the clinic for treatment. Three women were due to have a hysterectomy and were not offered treatment, another was followed colposcopically, and another moved out of the area. The remainder (n=152) returned for treatment, including two women who had become pregnant and returned to undergo further biopsies after their pregnancies were completed.

Overtreatment by large loop excision

In the immediate large loop excision arm, 59% (432) of the women from whom specimens were taken had no cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (31%) or grade I disease (28%). Thus according to the National Cancer Institute’s definition, 59% of women were overtreated; by the NHS cervical screening programme definition, 31% were overtreated.

Cumulative incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia over three years

The cumulative incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse was slightly higher in the immediate large loop excision arm (84/1000 person years v 79/1000), but the adjusted relative risk was not significantly raised (relative risk large loop excision v biopsy 1.04, 0.86 to 1.25) (table 3). The rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III or worse in each arm were about half those of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse and the adjusted relative risk did not differ from unity (1.03, 0.79 to 1.34).

Table 3.

Incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or grade III or worse after three years of follow-up, by trial arm and period of follow-up

| Biopsy and recall | Immediate large loop excision | Relative risk* (95% CI), P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (% of those in arm) | % of disease detected | No (% of those in arm) | % of disease detected | |||

| Total women randomised | 1000 (100) | — | 983 (100) | — | — | |

| Total person years of follow-up | 2731 | — | 2725 | — | — | |

| Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse | ||||||

| Total cases† | 216 (22) | 100 | 228 (23) | 100 | — | |

| At initial colposcopy | 160 (16) | 74 | 202 (21) | 89 | — | |

| At follow-up | 32 (3) | 15 | 18 (2) | 8 | — | |

| At exit examination | 24 (2) | 11 | 8 (1) | 4 | — | |

| Cumulative incidence per 1000 person years§ | 79 | — | 84 | — | 1.04 (0.86 to 1.25), P=0.687 | |

| Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III or worse | ||||||

| Total cases† | 107 (11) | 100 | 113 (11) | 100 | — | |

| At initial colposcopy | 83 (8) | 78 | 102 (10) | 90 | — | |

| At follow-up | 19 (2) | 18 | 10 (1) | 9 | — | |

| At exit examination | 5 (1) | 5 | 1 (0.1) | 1 | — | |

| Cumulative incidence per 1000 person years§ | 39 | — | 41 | — | 1.03 (0.79 to 1.34), P=0.841 | |

*Relative risk (with biopsy and recall as reference) based on total number of cases and adjusted for age (20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59), cytology at recruitment (mild dyskaryosis, borderline nuclear abnormalities), centre (Grampian, Tayside, Nottingham), and high risk human papillomavirus status (positive, negative, unknown).

‡Includes four women who had disease worse than cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III; three detected after initial colposcopy and treatment (one in biopsy and recall arm, two in immediate large loop excision arm), and one detected during follow-up in biopsy and recall arm.

There was no difference between the policies in the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse or grade III or worse over three years in subgroups defined by age or recruitment cytology (table 4). Similarly, when we restricted the analysis to the 1637 women with no previous cytology showing borderline nuclear abnormalities, the occurrence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse did not differ between the arms (adjusted relative risk 0.99, 0.81 to 1.22; P=0.956).

Table 4.

Incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or grade III or worse after three years of follow-up, stratified by age and recruitment cytology

| Outcome and subgroup | Biopsy and recall | Immediate large loop excision | Relative risk* (95% CI) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) of cases | Cumulative incidence | No (%) of cases | Cumulative incidence | ||||

| Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse | |||||||

| Age (years): | |||||||

| 20-29 | 134 (31) | 116 | 137 (32) | 117 | 1.01 (0.80 to 1.29) | 0.904 | |

| 30-59 | 82 (14) | 52 | 91 (16) | 59 | 1.07 (0.79 to 1.44) | 0.657 | |

| Cytology†: | |||||||

| Mild dyskaryosis | 129 (36) | 134 | 120 (35) | 125 | 0.90 (0.70 to 1.16) | 0.424 | |

| Borderline nuclear abnormalities | 87 (14) | 49 | 108 (17) | 61 | 1.24 (0.94 to 1.65) | 0.132 | |

| Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III or worse | |||||||

| Age (years): | |||||||

| 20-29 | 69 (16) | 60 | 69 (16) | 59 | 0.99 (0.71 to 1.38) | 0.950 | |

| 30-59 | 38 (7) | 24 | 44 (8) | 28 | 1.10 (0.71 to 1.70) | 0.673 | |

| Cytology‡: | |||||||

| Mild dyskaryosis | 67 (19) | 69 | 59 (17) | 62 | 0.84 (0.59 to 1.19) | 0.332 | |

| Borderline nuclear abnormalities | 40 (6) | 23 | 54 (8) | 31 | 1.35 (0.90 to 2.04) | 0.146 | |

*Comparison for immediate large loop excision v biopsy and recall (reference group). Adjusted for age (20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, as appropriate), recruitment cytology (mild dyskaryosis, borderline nuclear abnormalities, as appropriate), centre (Grampian, Tayside, Nottingham), and high risk human papillomavirus status (positive, negative, unknown).

†Result of cytology test that triggered recruitment into trial; women might have had up to one additional smear showing borderline nuclear abnormalities in previous three years.

Timing of detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse

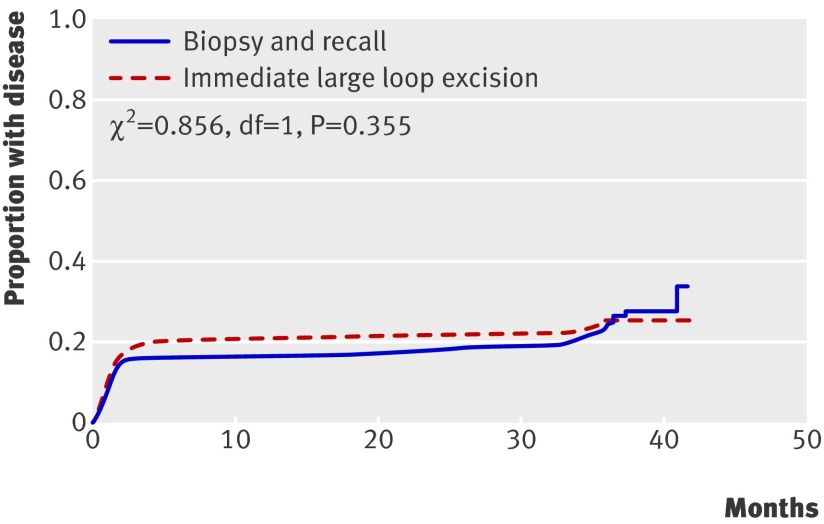

Almost 90% of cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse in the immediate large loop excision arm were diagnosed as a result of the initial colposcopy and any related procedures, compared with 74% in the biopsy and recall arm (table 3). In the biopsy and recall arm a quarter of cases were detected during follow-up (15%, n=32) and at exit (11%, n=24), compared with 12% in the immediate large loop excision arm (8%, n=18, during follow-up; 4%, n=8, at exit). Time of detection, however, was not significantly different between the arms (fig 2; log rank χ2 0.856, df=1, P=0.355). These patterns were the same when we repeated the analysis for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III or worse (Kaplan-Meier curve not shown; log rank χ2 0.358, df=1, P=0.550).

Fig 2 Cumulative proportion of women developing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or more severe disease from trial recruitment up to and including exit examination, by trial arm (χ2 from log rank test)

Morbidity

In the immediate large loop excision arm there were two cases of haemorrhage and seven vasovagal events in the clinic. In the other arm, there was one case of haemorrhage and one vasovagal event after punch biopsy and one woman haemorrhaged after treatment.

Women’s reports of pain after the initial colposcopy and related procedures did not differ by arm (table 5). Although the occurrence of any bleeding was higher in the biopsy and recall arm, this was of significantly longer duration (P<0.001) and more likely to be moderate or more severe (P=0.022) in the immediate large loop excision arm. Similar findings were seen for discharge.

Table 5.

Morbidity at six weeks after procedure* and incidence of clinically significant anxiety and depression by trial arm†. Figures are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Biopsy and recall (n=361‡) | Immediate large loop excision (n=400§) | Difference in % between arms (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain: | ||||

| Any pain | 143 (39.7) | 153 (38.7) | −1.0 (−8.0 to 6.0) | 0.781 |

| Median (IQR) duration (days) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | 0.782 | |

| Moderate or more severe | 68 (19.0) | 75 (19.2) | 0.2 (−5.4 to 5.9) | 0.935 |

| Bleeding: | ||||

| Any bleeding | 182 (50.4) | 171 (43.5) | −6.9 (−14.0 to 0.2) | 0.058 |

| Median (IQR) duration (days) | 3 (2-5) | 8 (3-20) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate or more severe | 55 (15.3) | 84 (21.9) | 6.5 (1.0 to 12.1) | 0.022 |

| Discharge: | ||||

| Any discharge | 122 (33.9) | 139 (35.3) | 1.3 (−5.5 to 8.1) | 0.709 |

| Median (IQR) duration (days) | 3 (2-7) | 9 (3-14) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate or more severe | 46 (12.8) | 84 (21.4) | 8.6 (3.2 to 13.9) | 0.002 |

| Anxiety¶ | 32 (9.4) | 26 (6.8) | −2.6 (−6.6 to 1.4) | 0.203 |

| Depression** | 27 (7.9) | 22 (5.7) | −2.2 (−5.9 to 1.5) | 0.239 |

IQR=interquartile range.

*Questionnaires administered about six weeks after last procedure, whether colposcopy, punch biopsies, or large loop excision, to 502 women in biopsy and recall arm and 487 in immediate large loop excision arm.

†Intention to treat analyses. Biopsy and recall group includes women managed by colposcopy only, colposcopy and punch biopsies, or colposcopy, punch biopsies, and large loop excision; immediate large loop excision group includes women managed by colposcopy only, or colposcopy and large loop excision.

‡Number who responded to questionnaire; number who responded to individual questions on pain, bleeding, and discharge varied between 358 and 361; anxiety based on 341 respondents; depression based on 343 respondents.

§Number who responded to questionnaire; numbers who responded to individual questions on pain, bleeding, and discharge varied between 385 and 395; anxiety based on 382 respondents; depression based on 387 respondents.

¶≥11 on hospital anxiety and depression scale anxiety subscale.

**≥8 on hospital anxiety and depression scale depression subscale.

A slightly higher percentage of women in the biopsy and recall arm scored ≥11 on the hospital anxiety and depression scale anxiety subscale six weeks after the procedure, but this was not significant (P=0.203). There was no significant difference in the frequency of depression (subscale score ≥8) by arm (P=0.239).

Discussion

In this randomised controlled trial comparing management options at colposcopy for women with low grade abnormal cytology, colposcopists were significantly less likely to classify the transformation zone as abnormal in women who were to be managed by large loop excision than in those who were to be managed by punch biopsies. Although more cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse was detected initially in the immediate large loop excision arm, and the incidence of disease during follow-up and at the exit examination was higher in the biopsy and recall arm, the timing of detection of disease did not differ significantly between the arms. Thus, overall there was no significant difference in ability of the policies to detect grade II neoplasia or worse over three years. This finding did not vary by age group or recruitment cytology. Specimens from 28% of women who underwent immediate large loop excision showed grade I neoplasia, and a further 31% had no cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Of women managed by punch biopsies, 16% were recalled for treatment. Higher proportions of women randomised to large loop excision reported moderate or more severe bleeding and discharge. As no aspect of screening is without some disadvantages, the challenge in synthesising these findings is that of maximising benefits while minimising harms.

Colposcopic thresholds

The higher percentage of women assessed as having an abnormal transformation zone in the biopsy and recall arm could be a true difference or a result of variation in colposcopic assessment between observers,32 33 but these explanations are unlikely given that the study was randomised and the randomisation was stratified by centre (each colposcopist worked in one centre). In addition, comparison of the seven trial colposcopists and one external colposcopist found moderate to high agreement between raters on presence of acetowhitening in colposcopic images from 124 women. More plausible explanations are that colposcopists might be more reluctant to do a large loop excision if there is ambiguity about the normality of the transformation zone, or if colposcopists’ threshold to identify a relevant lesion and perform a biopsy is lower if the proposed intervention is punch biopsy. As the higher frequency of intervention in the biopsy and recall arm did not result in significantly higher detection of high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, this suggests that the colposcopic threshold at which the decision is made to undertake punch biopsy is too low.

Targeted biopsies and missed prevalent disease

The concerns about the safety of a policy of biopsy and selective recall, in terms of missing relevant disease, tend to have been expressed in the context of women with high grade abnormal cytology,17 in whom the underlying prevalence of high grade disease would be higher than in women with low grade abnormal cytology. In some instances where prevalent disease has been missed this was probably due, at least in part, to inadequate biopsy practice. A trial of women with low grade abnormal cytology in the United States, known as ALTS, found that diagnostic accuracy depended more on the number of biopsies taken rather than the colposcopist’s experience.34 Within the current trial, colposcopic practice followed NHS cervical screening programme guidelines,2 which recommend a minimum of two punch biopsies; this was done in more than 90% of women. Despite this, the frequency of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse (and of grade III or worse) was still higher after the initial colposcopy in the large loop excision arm, suggesting that pathologists find more high grade disease if they have large loop excision samples than if they have punch biopsy samples.

If prevalent high grade disease was missed in women on biopsy and recall, we would expect more high grade lesions to be detected during follow-up and at exit examination in this arm, which is what we saw. The difference between arms, however, was not pronounced (3% and 2% of women on biopsy and recall had cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse detected during follow-up and at exit, respectively, compared with 2% and 1% on immediate large loop excision) and was mainly accounted for by grade II disease (32/56 were grade II in the biopsy and recall group; 15/26 were grade II in the immediate large loop excision group). In addition, there was no significant difference between arms in the timing of detection of disease. Moreover, in each arm 15 of the cases that occurred during follow-up were in women with a normal transformation zone at initial colposcopy, a few of whom probably harboured lesions at recruitment that were undetected at that time. As the frequency of microinvasive and invasive disease over three years was low (two cases in each arm), and there was no difference in the cumulative disease incidence between arms, these observations suggest that biopsy and recall is not associated with delays that increase the risk of high grade or invasive disease, at least over three years. Thus although some undercalling might occur at the time of colposcopy, the policy is safe for the management of women with low grade abnormal cytology within the NHS cervical screening programmes.

Overtreatment by large loop excision and risk of high grade disease in women with untreated grade I neoplasia

Despite the higher threshold for intervention in the immediate large loop excision arm, 31% of specimens contained no cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. This is well above the NHS cervical screening programme standard (<10%) and is partly due to the trial protocol where all abnormalities were treated by large loop excision; in the real world, alternatives are available.

In almost 30% of women who had immediate large loop excision, the histology indicated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade I; the proportion with grade I disease was the same among women randomised to biopsy and recall who had an abnormal transformation zone. Much of the debate around the relative benefits and harms of the management policies hinges on whether grade I disease needs to be removed to reduce risk of subsequent high grade disease. If so, women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade I managed by a policy of immediate large loop excision would not be considered to have had unnecessary treatment, while those managed by punch biopsies and selective recall might be considered to be undertreated. In ALTS, 13% of women with grade I neoplasia developed grade II/III disease over two years.35 As screening programmes reduce but do not eliminate risk of disease,25 the key issue for a policy of biopsy and recall is whether incident high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in women with grade I disease would be detected and treated as part of routine follow-up before it progresses to invasive disease. In the current trial, follow-up was based on standard NHS cervical screening programme protocols. Among the 168 women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade I in the biopsy and recall arm, 12 (7.1%) cases of grade II disease or worse were diagnosed during follow-up and a further five (3.0%) were found at the exit examination (although this was not part of standard follow-up); no cases were more severe than grade III. This suggests that the risk of incident high grade disease in women with low grade abnormal cytology in the NHS cervical screening programmes and grade I neoplasia on punch biopsy is relatively low and that most cases will be safely detected (and treated) during routine follow-up.

Morbidity associated with management policies

The higher occurrence of haemorrhage and vasovagal events in the large loop excision arm was unsurprising given that both are recognised risks of the procedure.11 Although clinically important, recording complications during procedures does not capture other physical after effects that women might experience, such as ongoing pain or discharge. Our analysis in this paper was by intention to treat so probably underestimates the true difference between policies. An analysis of after effects based on management received by women is reported elsewhere.36 As size of excision has previously been positively associated with occurrence of bleeding,37 the observed higher frequencies of moderate or more severe bleeding and discharge in the immediate large loop excision arm might have been expected.

As women who participate in trials might be systematically different from those who do not, it is not clear that our findings regarding overall levels of anxiety or depression will be generalisible to all women with low grade abnormal cytology. The internal comparison of the trial arms, however, is valid. Our observation of no notable difference between arms in anxiety after the procedure contrasts with the results of Balasubramani et al.24 In a non-randomised study of 272 women with high grade smear results, women who had immediate large loop excision reported lower anxiety and greater relief one week after the intervention than those undergoing biopsy and recall for treatment. The instruments for assessing outcomes, and timing of these, differed from those in our trial. In addition, information given to women with high grade abnormal cytology, and their expectations and emotional and psychosocial responses, might differ from women with low grade abnormal cytology.

Recall for treatment: costs and default

One of the major potential limitations of a policy of biopsies and selective recall is the need for a proportion of women (16% of those randomised) to return for treatment. The colposcopy clinic incurs the cost of an additional appointment and women themselves experience both inconvenience and time and travel costs, the latter estimated at more than £27 (€32, $44) per clinic visit.38 In our economic analysis, the cost effectiveness ratios of the two management policies did not differ significantly.26 What remains unknown, however, is how women themselves balance the advantage with see-and-treat of avoiding the cost and inconvenience of a second clinic visit against the risk of overtreatment and increased physical after effects.

A further potential drawback of biopsy and recall is that women might not attend the treatment appointment, therefore increasing their risk of developing invasive disease. The high rate of return for treatment in the biopsy and recall arm probably reflects the commitment of trial participants and might not generalise to routine clinical practice.

Strengths and limitations

This trial was large, population based, and pragmatic. The overall participation rate was 52%. As regards generalisibility of the results to the NHS cervical screening programme, the ratio of borderline nuclear abnormalities to mild recruitment smear results among participants (1.8:1) was close to that reported for the programme screening age group in 2004-5 (1.9:1).39 40

Despite strenuous attempts to maximise attendance,28 a third of participants did not attend the exit examination. Those who did not attend were more likely to be young, be from non-white ethnic groups, have only mildly abnormal results at recruitment, live in areas in the two most deprived categories, and be smokers at recruitment. As several of these are risk factors for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II/III and cervical cancer,41 42 43 the overall cumulative incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse was probably underestimated. The extent of the underestimation is probably small, however, as only 32 new cases were found at the exit examination (2.4% of attendees). In addition, the incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or worse up to, but not including, the exit examination (14% and 33% for those with recruitment smears showing borderline nuclear abnormalities and mild dyskaryosis, respectively), were similar to figures from two studies that followed participants in the NHS cervical screening programme with borderline nuclear abnormalities and mild dyskaryosis for five years (13% and 28%,44 13% and 36%45). When we restricted our analysis to women who had attended the exit examination, the results were unchanged (adjusted relative risk for grade II or worse, large loop excision v biopsy 1.02, 0.81 to 1.28).

A greater proportion of women in the biopsy and selective recall arm had their clinical outcomes determined from review of medical and hospital records and pathology databases. As some women who did not attend the exit examination might have had undiagnosed disease, the differential attendance at exit by arm is a limitation of the trial. In theory the burden of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia might have been underestimated to a greater extent in the biopsy and recall arm than in the other arm, meaning that we failed to detect a true difference between the arms. Given the low frequency of high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at exit, however, only a few additional cases would have been detected had attendance in the biopsy and recall arm been as high as in the other arm, and this would not have had a sufficient impact on cumulative incidence to change the main findings.

In recognition of its limitations, the role of colposcopy was restricted to categorising the transformation zone as normal or abnormal. Although large loop excision became the most common treatment method for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia during the 1990s, ablative treatment is still widely used and might offer advantages over excision, especially for young nulliparous women.46 47 In the current trial, women treated after punch biopsies had large loop excision (to ensure complete histological assessment of the transformation zone), but we consider that our findings would also apply to a policy of subsequent ablative treatment.

Conclusions

When carried out in the context of a quality assured screening programme with recognised colposcopy accreditation and national standards for colposcopy, targeted punch biopsy and selective treatment of high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia provides the best balance between benefits and harms for the management of women seen for colposcopic assessment of low grade abnormal cytology. The policy does not miss important disease, and, although a proportion of women are recalled for treatment, it is as cost effective as immediate large loop excision. Immediate large loop excision is not recommended as there is a considerable risk of overtreatment and more after effects.

What is already known on this topic

Each year, many women with low grade abnormal cytology detected by cervical screening are referred for colposcopic examination but the most effective management policy at colposcopy is uncertain

Immediate treatment by large loop excision (“see-and-treat”) might be efficient for clinic organisation, but results in women without cervical intraepithelial neoplasia being treated

Targeted punch biopsies with selective recall for treatment for high grade disease might miss disease present at colposcopy, and untreated women with low grade lesions could subsequently develop high grade disease

What this study adds

A policy of targeted punch biopsy lowers the threshold for the colposcopic definition of abnormality compared with large loop excision; more women are classified as having an abnormal transformation zone and undergo biopsy

A policy of see-and-treat results in substantial overtreatment and more after effects than punch biopsies and selective recall

Detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II or more severe disease over three years of follow-up does not differ significantly between the policies

A policy of see and treat confers no clear advantage over a policy of punch biopsies with recall for treatment, and the latter provides the best balance between benefits and harms

We are grateful for the cooperation and assistance that we received from NHS staff in the coordinating centres and clinical sites. We thank the women who participated in TOMBOLA.

The TOMBOLA Group

Grant holders: Maggie Cruickshank, Graeme Murray, David Parkin, Louise Smart, Eric Walker, Norman Waugh (principal investigator 2004-9) (University of Aberdeen and NHS Grampian, Aberdeen, Scotland); Mark Avis, Claire Chilvers, Katherine Fielding, Rob Hammond, David Jenkins, Jane Johnson, Keith Neal, Ian Russell, Rashmi Seth, Dave Whynes (University of Nottingham and Nottingham NHS, Nottingham, England); Ian Duncan, Alistair Robertson (University of Dundee and NHS Tayside, Dundee, Tayside); Julian Little (Principal Investigator 1999-2004) (University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada); Linda Sharp (National Cancer Registry, Cork, Ireland); Ian Russell (Bangor University, Bangor, Wales); Leslie Walker (University of Hull, Hull, England).

Staff in clinical sites and coordinating centres: Breda Anthony, Sarah Bell, Adrienne Bowie, Katrina Brown, Joe Brown, Kheng Chew, Claire Cochran, Seonaidh Cotton, Jeannie Dean, Kate Dunn, Jane Edwards, David Evans, Julie Fenty, Al Finlayson, Marie Gallagher, Nicola Gray, Maureen Heddle, Alison Innes, Debbie Jobson, Mandy Keillor, Jayne MacGregor, Sheona Mackenzie, Amanda Mackie, Gladys McPherson, Ike Okorocha, Morag Reilly, Joan Rodgers, Alison Thornton, Rachel Yeats (Grampian); Lindyanne Alexander, Lindsey Buchanan, Susan Henderson, Tine Iterbeke, Susanneke Lucas, Gillian Manderson, Sheila Nicol, Gael Reid, Carol Robinson, Trish Sandilands (Tayside); Marg Adrian, Ahmed Al-Sahab, Elaine Bentley, Hazel Brook, Claire Bushby, Rita Cannon, Brenda Cooper, Ruth Dowell, Mark Dunderdale, Dr Gabrawi, Li Guo, Lisa Heideman, Steve Jones, Salli Lawson, Zoë Philips, Christopher Platt, Shakuntala Prabhakaran, John Rippin, Rose Thompson, Elizabeth Williams, Claire Woolley (Nottingham).

Statistical analysis: Massoud Boroujerdi, Seonaidh Cotton, Kirsten Harrild, John Norrie.

External trial steering committee: Nicholas Day (chair, 1999-2004), Theresa Marteau (chair 2004-current), Mahesh Parmar, Julietta Patnick, Ciaran Woodman.

External data monitoring and ethics committee: Doug Altman (chair), Sue Moss, Michael Wells.

Contributors: Linda Sharp (guarantor), Maggie Cruickshank, Julian Little, Seonaidh Cotton, Kirsten Harrild, Claire Cochran, Ian Duncan, Nicola Gray, Rob Hammond, Louise Smart, Alison Thornton, Norman Waugh, and Claire Woolley carried out these analyses and wrote the paper.

Funding: This study was funded by the Medical Research Council (grant No G9700808) and the NHS in England and Scotland.

Competing interests: During the past five years ID has served on British and European Boards advising GlaxoSmithKline regarding the connection between human papillomavirus and cervical neoplasia for which he has received expenses and fees for professional services. He has participated in a symposium sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline as part of a EUROGIN conference in Paris and was partly sponsored as a result. He has assisted in GlaxoSmithKline’s and MSD Sanofi Pasteur’s education programmes increasing professional awareness of the link between the human papillomavirus and cervical neoplasia, receiving fees for his professional services in creating a set of educational slides and lecturing to doctors and nurses. JL has received fees from GlaxoSmithKline as a member of an independent data and safety monitoring committee for a trial of the efficacy of vaccination against HSV. NG was reimbursed for attending an international clinical advisory board on health related quality of life issues related to cervical cancer in April 2005 by GlaxoSmithKline.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the joint research ethics committee of NHS Grampian and the University of Aberdeen, the Tayside committee on medical research ethics, and the Nottingham research ethics committee. All participants provided informed consent.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b2548

References

- 1.NHS Cervical Screening Programmes. Standards and quality in colposcopy. Sheffield: NHS Cervical Screening Programme, 1996. ( NHSCSP Publication No 2.)

- 2.NHS Cervical Screening Programmes. Colposcopy and programme management guidelines for the NHS cervical screening programme. Sheffield: NHS Cervical Screening Programmes, 2004. (NHSCSP Publication No 20.)

- 3.TOMBOLA Group. Refining the management of low-grade cervical abnormalities in the UK National Health Service, and defining the potential for HPV testing: a commentary on emerging evidence. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2006;10:26-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker EM, Dodgson J, Duncan ID. Does mild atypia on a cervical smear warrant further investigation? Lancet 1986;2:672-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flannelly G, Anderson D, Kitchener H, Mann E, Campbell M, Fisher P, et al. Management of women with mild and moderate cervical dyskaryosis. BMJ 1994;308:1399-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitchener HC, Cruickshank ME, Farmery E. The 1993 British Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology/National Coordinating Network United Kingdom colposcopy survey. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995;102:549-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Hamont D, van Ham MA, Struik-van der Zanden PH, Keijser KG, Bulten J, Melchers WJ, et al. Long-term follow-up after large-loop excision of the transformation zone: evaluation of 22 years treatment of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2006;16:615-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holschneider CH, Ghosh K, Montz FJ. See-and-treat in the management of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions of the cervix: a resource utilization analysis. Obstet Gynecol 1999;94:377-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn TS, Burke M, Shwayder J. A “see and treat” management for high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion pap smears. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2003;7:104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheungraber C, Kleekamp N, Schneider A. Management of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions of the uterine cervix. Br J Cancer 2004;90:975-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardenas-Turanzas M, Follen M, Benedet JL, Cantor SB. See-and-treat strategy for diagnosis and management of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions. Lancet Oncol 2005;6:43-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kyrgiou M, Koliopoulos G, Martin-Hirsch P, Arbyn M, Prendiville W, Paraskevaidis E. Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for intraepithelial or early invasive cervical lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2006;367:489-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeronimo J, Schiffman M. Colposcopy at a crossroads. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:349-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buxton EJ, Luesley DM, Shafi MI, Rollason M. Colposcopically directed punch biopsy—a potentially misleading investigation. Br J Obstet Gynecol 1991;98:1273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allard JE, Rodriguez M, Rocca M, Parker MF. Biopsy site selection during colposcopy and distribution of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2005;9:36-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guido RS, Jeronimo J, Schiffman M, Solomon D, ALTS Group. The distribution of neoplasia arising on the cervix: results from the ALTS trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;193:1331-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byrom J, Douce G, Jones PW, Tucker H, Millinship J, Dhar K, et al. Should punch biopsies be used when high-grade disease is suspected at initial colposcopic assessment? A prospective study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2006;16:253-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostor AG. Natural history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a critical review. Int J Gynecol Path 1993;12:186-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howe DT, Vincenti AC. Is large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) more accurate than colposcopically directed punch biopsy in the diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia? Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1991;98:588-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonardi R, Cecchini S, Grazzini G, Ciatto S. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure of the transformation zone and colposcopically directed punch biopsy in the diagnosis of cervical lesions. Obstet Gynecol 1992;80:1020-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massad LS, Halperin CJ, Bitterman P. Correlation between colposcopically directed biopsy and cervical loop excision. Gynecol Oncol 1996;6:400-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denny LA, Soeters R, Dehaeck K, Bloch B. Does colposcopically directed punch biopsy reduce the incidence of negative LLETZ. Br J Obstet Gynecol 1995;102:545-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadan O, Yarden H, Schejter E, Bilevsky E, Bachar R, Lurie S. Treatment of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: a “see and treat” versus a three-step approach. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2007;131:73-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balasubramani L, Orbell S, Hagger M, Brown V, Tidy J. Do women with high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia prefer a see and treat option in colposcopy? Br J Obstet Gynecol 2007;114:39-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raffle AE, Gray JAM. Screening. Evidence and practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- 26.TOMBOLA Group. Options for managing low grade cervical abnormalities detected at screening: cost effectiveness study. BMJ 2009;339:b2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.TOMBOLA Group. Cytological surveillance compared with immediate referral for colposcopy in management of women with low grade cervical abnormalities: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009:389:b2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Cotton SC, Sharp L, Little J, Duncan I, Alexander L, Cruickshank ME, et al. Trial of management of borderline and other low-grade abnormal smears (TOMBOLA): trial design. Contemp Clin Trials 2006;27:449-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapter 4. The colposcope and techniques of colposcopy. In: Luesley DM, Shafi MI, Jordan JA, eds. Handbook of colposcopy. 2nd ed. London: Hodder Arnold, 2002.

- 30.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Cancer Institute (NCI). Treatment information for health professionals. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2004.

- 32.Etherington IJ, Luesley DM, Shafi MI, Dunn J, Hiller L, Jordan JA. Observer variability among colposcopists from the West Midlands region. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:1380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferris DG, Litaker M, ALTS G. Interobserver agreement for colposcopy quality control using digitized colposcopic images during the ALTS trial. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2005;9:29-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gage JC, Hanson VW, Abbey K, Dippery S, Gardner S, Kubota J, et al. Number of cervical biopsies and sensitivity of colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:264-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cox JT, Schiffman M, Solomon D, ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) Group. Prospective follow-up suggests similar risk of subsequent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 among women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1 or negative colposcopy and directed biopsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188:1406-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.TOMBOLA Group. After-effects reported by women following colposcopy, cervical biopsies and LLETZ: results from the TOMBOLA trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2009; Jul 7 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Doyle M, Warwick A, Redman C, Hillier C, Chenoy R, O’Brien S. Does application of Monsel’s solution after loop diathermy excision of the transformation zone reduce post operative discharge? Results of a prospective randomised controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1992;99:1023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woolley C, Philips Z, Whynes DK, Cotton SC, Gray NM, Sharp L, et al. United Kingdom cervical cancer screening and the costs of time and travel. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2007;23:232-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cervical cytology workload statistics. www.isdscotland.org/cervical_screening.

- 40.Cervical Screening Programme, England: 2004-2005. www.ic.nhs.uk/pubs/cervicscrneng2005.

- 41.Castellsague X, Munoz N. Chapter 3: Cofactors in human papillomavirus carcinogenesis—role of parity, oral contraceptives, and tobacco smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003;31:20-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parikh S, Brennan P, Boffetta P. Meta-analysis of social inequality and the risk of cervical cancer. Int J Cancer 2003;105:687-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bosch FX, Iftner T. The aetiology of cervical cancer. Sheffield: NHS Cancer Screening Programmes, 2005.

- 44.Rana DN, Marshall J, Desai M, Kitchener HC, Perera DM, El Teraifi H, et al. Five-year follow-up of women with borderline and mildly dyskaryotic cervical smears. Cytopathol 2004;15:263-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith MC, Keech SE, Perryman K, Soutter WP. A long-term study of women with normal colposcopy after referral with low-grade cytological abnormalities. Br J Obstet Gynecol 2006;113:1321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duncan ID, McKenzie CA, Wilson SM, Gurram S, Koppala S, Neillie LJ. Have we dismissed ablative treatment too soon in colposcopy practice? Br J Obstet Gynecol 2007;114:777-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paraskevaidis E, Kyrgiou M, Martin-Hirsch P. Have we dismissed ablative treatment too soon in colposcopy practice? Br J Obstet Gynecol 2007;114:3-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]