Abstract

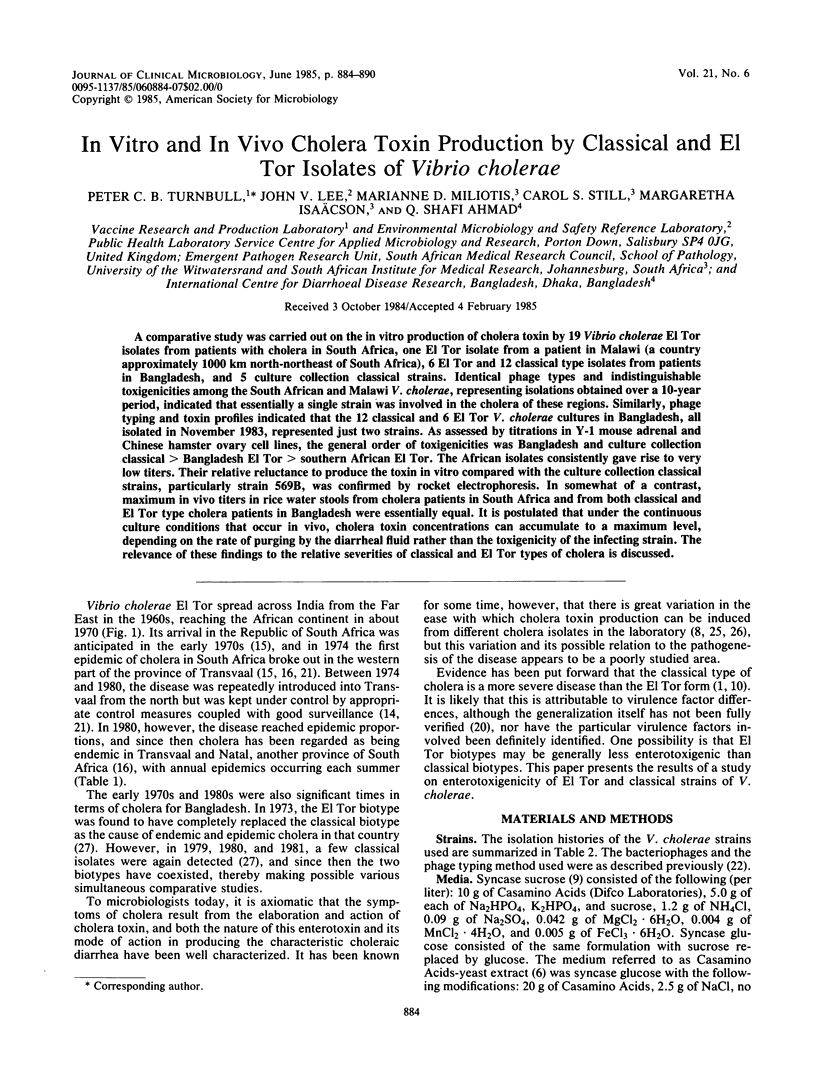

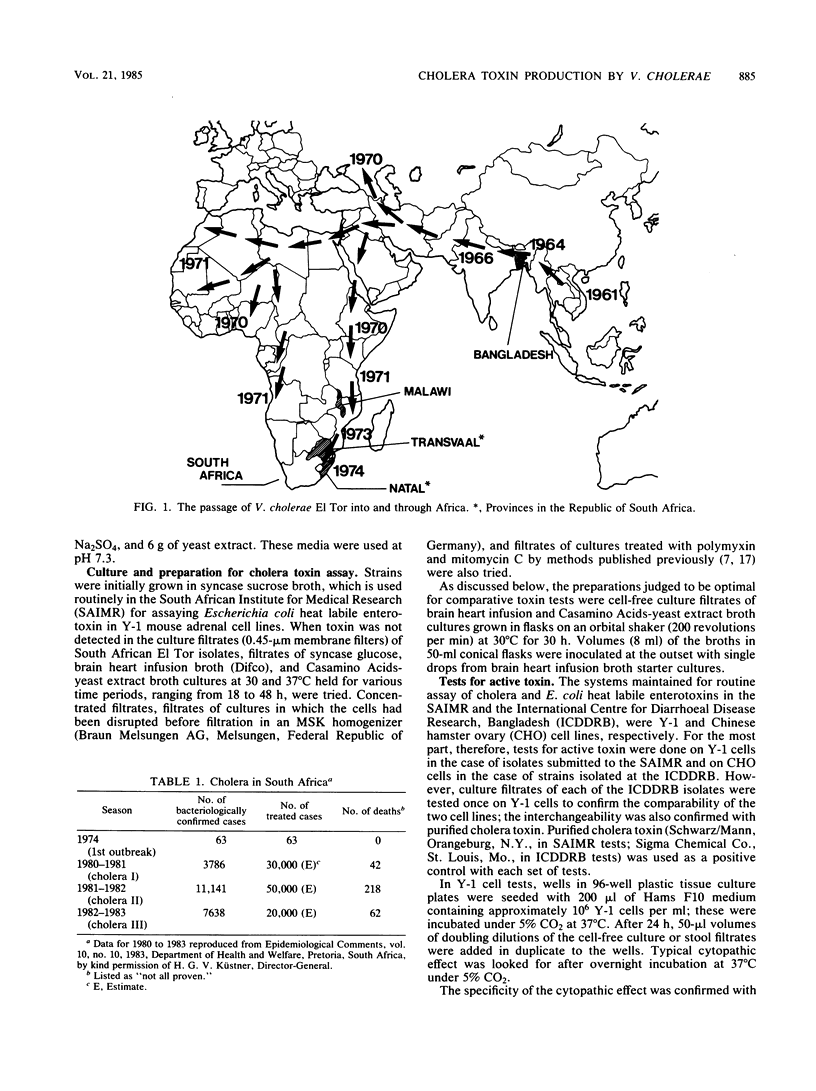

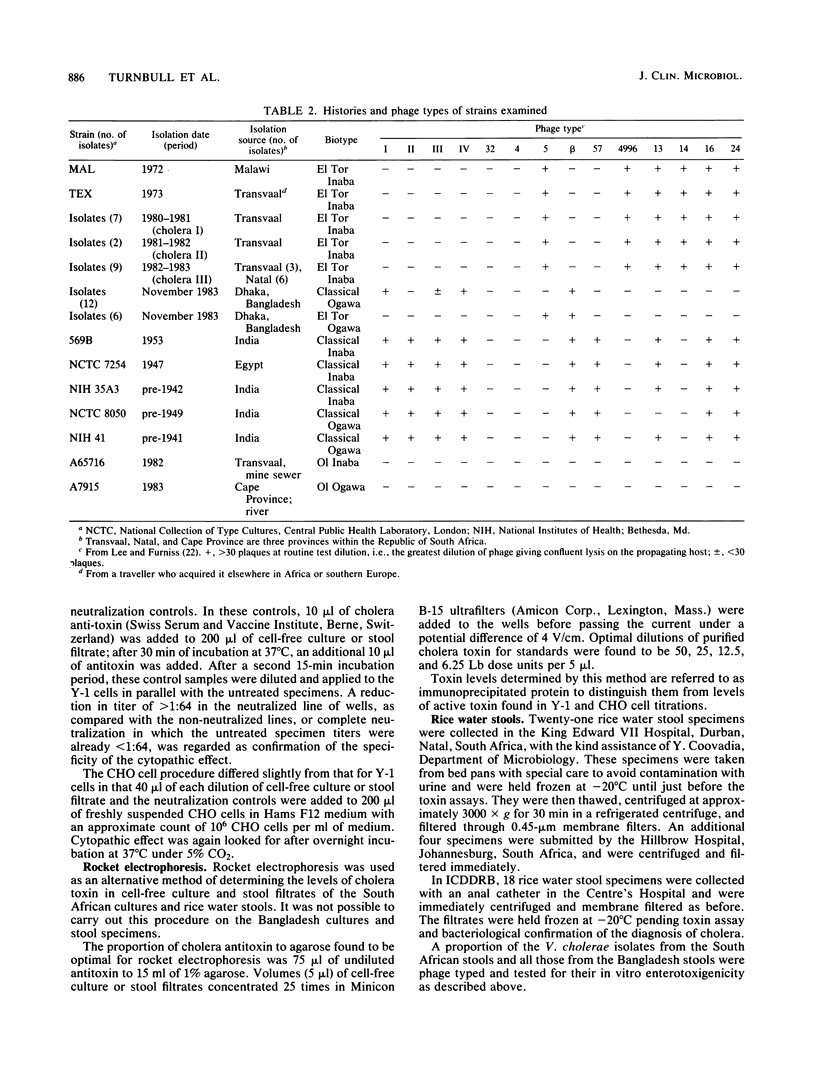

A comparative study was carried out on the in vitro production of cholera toxin by 19 Vibrio cholerae El Tor isolates from patients with cholera in South Africa, one El Tor isolate from a patient in Malawi (a country approximately 1000 km north-northeast of South Africa), 6 El Tor and 12 classical type isolates from patients in Bangladesh, and 5 culture collection classical strains. Identical phage types and indistinguishable toxigenicities among the South African and Malawi V. cholerae, representing isolations obtained over a 10-year period, indicated that essentially a single strain was involved in the cholera of these regions. Similarly, phage typing and toxin profiles indicated that the 12 classical and 6 El Tor V. cholerae cultures in Bangladesh, all isolated in November 1983, represented just two strains. As assessed by titrations in Y-1 mouse adrenal and Chinese hamster ovary cell lines, the general order of toxigenicities was Bangladesh and culture collection classical greater than Bangladesh El Tor greater than southern African El Tor. The African isolates consistently gave rise to very low titers. Their relative reluctance to produce the toxin in vitro compared with the culture collection classical strains, particularly strain 569B, was confirmed by rocket electrophoresis. In somewhat of a contrast, maximum in vivo titers in rice water stools from cholera patients in South Africa and from both classical and El Tor type cholera patients in Bangladesh were essentially equal. It is postulated that under the continuous culture conditions that occur in vivo, cholera toxin concentrations can accumulate to a maximum level, depending on the rate of purging by the diarrheal fluid rather than the toxigenicity of the infecting stain. The relevance of these findings to the relative severities of classical and El Tor types of cholera is discussed.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bart K. J., Huq Z., Khan M., Mosley W. H. Seroepidemiologic studies during a simultaneous epidemic of infection with El Tor Ogawa and classical Inaba Vibrio cholerae. J Infect Dis. 1970 May;121(Suppl):17+–17+. doi: 10.1093/infdis/121.supplement.s17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements J. D., Finkelstein R. A. Isolation and characterization of homogeneous heat-labile enterotoxins with high specific activity from Escherichia coli cultures. Infect Immun. 1979 Jun;24(3):760–769. doi: 10.1128/iai.24.3.760-769.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig J. P. A permeability factor (toxin) found in cholera stools and culture filtrates and its neutralization by convalescent cholera sera. Nature. 1965 Aug 7;207(997):614–616. doi: 10.1038/207614a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUTTA N. K., HABBU M. K. Experimental cholera in infant rabbits: a method for chemotherapeutic investigation. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1955 Jun;10(2):153–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1955.tb00074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. J., Evans D. G., Gorbach S. L. Polymyxin B-Induced Release of Low-Molecular-Weight, Heat-Labile Enterotoxin from Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1974 Nov;10(5):1010–1017. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.5.1010-1017.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. J., Jr, Evans D. G., Gorbach S. L. Production of vascular permeability factor by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from man. Infect Immun. 1973 Nov;8(5):725–730. doi: 10.1128/iai.8.5.725-730.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. J., Jr, Richardson S. H. In vitro production of choleragen and vascular permeability factor by Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 1968 Jul;96(1):126–130. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.1.126-130.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein R. A., Atthasampunna P., Chulasamaya M., Charunmethee P. Pathogenesis of experimental cholera: biologic ativities of purified procholeragen A. J Immunol. 1966 Mar;96(3):440–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary S. J., Marchlewicz B. A., Finkelstein R. A. Comparison of heat-labile enterotoxins from porcine and human strains of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1982 Apr;36(1):215–220. doi: 10.1128/iai.36.1.215-220.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill D. M. Multiple roles of erythrocyte supernatant in the activation of adenylate cyclase by Vibrio cholerae toxin in vitro. J Infect Dis. 1976 Mar;133 (Suppl):55–63. doi: 10.1093/infdis/133.supplement_1.s55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass R. I., Lee J. V., Huq M. I., Hossain K. M., Khan M. R. Phage types of Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor isolated from patients and family contacts in Bangladesh: epidemiologic implications. J Infect Dis. 1983 Dec;148(6):998–1004. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.6.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson R. E., Moon H. W. Induction of heat-labile enterotoxin synthesis in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli mitomycin C. Infect Immun. 1975 Dec;12(6):1271–1275. doi: 10.1128/iai.12.6.1271-1275.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaäcson M., Clarke K. R., Ellacombe G. H., Smit W. A., Smit P., Koornhof H. J., Smith L. S., Kriel L. J. The recent cholera outbreak in the South African gold mining industry. A preliminary report. S Afr Med J. 1974 Dec 14;48(61):2557–2560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaper J. B., Moseley S. L., Falkow S. Molecular characterization of environmental and nontoxigenic strains of Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun. 1981 May;32(2):661–667. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.2.661-667.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M. T., Peterson J. W., Sarles H. E., Jr, Romanko M., Martin D., Hafkin B. Cholera on the Texas Gulf Coast. JAMA. 1982 Mar 19;247(11):1598–1599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. U., Samadi A. R., Huq M. I., Yunus M., Eusof A. Simultaneous classical and El Tor cholera in Bangladesh. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1984 Mar;2(1):13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küstner H. G., Gibson I. H., Carmichael T. R., Van Zyl L., Chouler C. A., Hyde J. P., du Plessis J. N. The spread of cholera in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 1981 Jul 18;60(3):87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lönnroth I., Lönnroth C. Interaction of cholera toxin and its subunits with lymphocytes. The effects on intracellular cAMP. Exp Cell Res. 1977 Jan;104(1):15–24. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(77)90063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekalanos J. J., Swartz D. J., Pearson G. D., Harford N., Groyne F., de Wilde M. Cholera toxin genes: nucleotide sequence, deletion analysis and vaccine development. Nature. 1983 Dec 8;306(5943):551–557. doi: 10.1038/306551a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oza N. B., Dutta N. K. A study of the pathogenesis of El Tor and classical cholera vibrios in infant rabbits. Bull World Health Organ. 1970;42(4):642–646. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson S. H. Factors influencing in vitro skin permeability factor production by Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 1969 Oct;100(1):27–34. doi: 10.1128/jb.100.1.27-34.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samadi A. R., Huq M. I., Shahid N., Khan M. U., Eusof A., Rahman A. S., Yunus M., Faruque A. S. Classical Vibrio cholerae biotype displaces EL tor in Bangladesh. Lancet. 1983 Apr 9;1(8328):805–807. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91860-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]