Abstract

Mouse parotid acinar cells express P2X4 and P2X7 receptors (mP2X4R and mP2X7R) whose physiological function remains undetermined. Here we show that mP2X4R expressed in HEK-293 cells do not allow the passage of tetraethylammonium (TEA+) and promote little, if any, ethidium bromide (EtBr) uptake when stimulated with ATP or BzATP. In contrast, mP2X7R generates slowly decaying TEA+ current, sustained Na+ current and promotes robust EtBr uptake. However, ATP-activated TEA+ current from acinar cells was unlike that generated by mP2X7R or mP2X4R. Functional interactions between mP2X4R and mP2X7R were investigated in HEK cells co-transfected with different mP2X4 : mP2X7 cDNA ratios and using solutions containing either TEA+ or Na+ ions. Co-expressed channels generated a TEA+ current that displayed faster decay during ATP stimulation than mP2X7R alone. Moreover, cells transfected with a 2 : 1 cDNA ratio displayed decaying kinetics similar to those observed in acinar cells. Concentration–response curves in Na+-containing solutions were constructed for heterologously expressed mP2X4R, mP2X7R and mP2X4R:mP2X7R co-expressions as well as acinar cells. The EC50 values determined were 11, 220, 434 and 442 μm, respectively. Na+ currents generated by expressing mP2X4R or mP2X7R alone were potentiated by ivermectin (IVM). In contrast, IVM potentiation in acinar cells and HEK cells co-expressing P2X4 and P2X7 (1 : 1 or 2 : 1 cDNA ratios) was seen only when the ATP concentration was lowered from 5 to 0.03 mm. Taken together our observations indicate a functional interaction between murine P2X7 and P2X4 receptors. Such interaction might occur in acinar cells to shape the response to extracellular ATP in salivary epithelia.

The physiological responses to extracellular adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) are transduced by either non-selective P2X (P2X1–P2X7) ion channels or by G-protein coupled metabotropic P2Y (P2Y1–P2Y11) receptors (North, 2002; Burnstock, 2007). Secretory epithelial cells from salivary glands express P2X4 and P2X7 ionotropic and P2Y1 and P2Y2 metabotropic receptors but their physiological role remains unclear (Tenneti et al. 1998; Turner et al. 1998, 1999). Recently, it has been proposed that purinergic stimulation induces saliva secretion in mouse submandibular glands due to activation of P2X7 receptors (Nakamoto et al. 2009). P2X4 and P2X7 receptors are also co-expressed in immune cells such as microglia, monocytes and macrophages (Xiang & Burnstock, 2005; Bours et al. 2006) where they play a role in inflammation and pain. For example, maturation and release of pro-inflammatory interleukin-1β as well as development of neuropathic pain result from activation of P2X7R (Perreaux & Gabel, 1994; Solle et al. 2001; Chessell et al. 2005; Dinarello, 2005). In contrast, the role of P2X4R in immune cells is not yet well understood; nevertheless, it is believed that in microglia P2X4R makes a significant contribution to inflammatory responses and tactile allodynia after nerve injury (Tsuda et al. 2003; Raouf et al. 2007).

It has been shown that functionally active P2X receptors are assembled as homo- or heterotrimers (Torres et al. 1999). Biochemical and functional results indicate that P2X homomeric channels are produced by P2X1, P2X2, P2X3, P2X4, P2X5, or P2X7 subunits (North, 2002). Potential combinations of subunits to form heteromeric channels include: P2X1–P2X2 (Brown et al. 2002), P2X1–P2X4 (Nicke et al. 2005), P2X1–P2X5 (Torres et al. 1998), P2X2–P2X3 (Lewis et al. 1995), P2X2–P2X6 (King et al. 2000) or P2X4–P2X6 (Lêet al. 1998). Depending on subunit composition these channels display a variety of pharmacological and functional properties upon activation by external ATP (Lewis et al. 1995; King et al. 2000).

Until recently, there was no evidence that P2X7R could interact either functionally or physically with any other P2X receptor (Torres et al. 1999) suggesting that P2X7 functioned only as a homotrimer. However, new biochemical and functional data suggest that P2X7R subunits interact with P2X4R subunits and possibly form heteromeric channels (Guo et al. 2007). Moreover, such interaction between P2X7R and P2X4R seems to be of physiological relevance as suggested by previous reports from ciliated airway epithelia which endogenously express P2X4R and P2X7R and show ATP-activated currents with novel characteristics (Ma et al. 2006). Similarly, in salivary epithelia we have shown that the ATP-activated current is carried by both cations and anions (Arreola & Melvin, 2003; Reyes et al. 2008). This current is absent in knock-out mice lacking P2X7R (Li et al. 2005; Reyes et al. 2008) indicating that P2X7R is essential for generation of a non-selective pore. However, this finding does not rule out the possible participation of P2X4R. Indeed, we could not fully reproduce the characteristics of the whole cell current activated by ATP in acinar cells by heterologous expression of P2X7R alone in HEK 293, indicating that the native current might result from interaction between P2X4R and P2X7R.

In this work, we show evidence which indicates these two P2X receptors functionally interact in a heterologous system as well as in native parotid acinar cells. Our new findings indicate that in secretory epithelia P2X4 and P2X7 receptors work together to produce an ATP-activated current with distinctive functional and pharmacological characteristics. Our results have been partially published in abstract form (Casas-Pruneda et al. 2007, 2008).

Methods

Single parotid acinar cell dissociation

Animal handling procedures were performed in accordance with regulations of the Animal Care and Use Internal Committee (Comite Interno para el Ciudado y Uso de Animales de Laboratorio; CICUAL) of the Universidad Autonoma de San Luis Potosi. Single acinar cells were dissociated from C57Black mice parotid glands using a previously published protocol (Arreola et al. 1995). Briefly, mice were placed under CO2 anaesthesia for 30 s and then exsanguinated before dissecting both parotid glands. Glands were minced in Ca2+-free minimum essential medium (SMEM; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) supplemented with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Fraction V; Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA). The tissue was treated for 20 min (37°C) in SMEM containing 0.02% trypsin + 1 mm EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) + 2 mm glutamine + 1% BSA. Digestion was stop with 2 mg ml−1 of soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma Chemical Co.). The tissue was further dispersed by two sequential treatments of 30 and 10 min with liberase (0.02–0.04 mg ml−1, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) in SMEM + 2 mm glutamine + 1% BSA. Dispersed cells were centrifuged and washed with basal medium Eagle (BME; Gibco BRL). The final pellet was resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco BRL) + 0.1 mg ml−1 gentamicin + 0.11 mg ml−1 sodium pyruvate + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and cells plated onto glass coverslips for electrophysiological recordings.

Culture and transient transfection of HEK-293 cells

HEK-293 cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were maintained in DMEM (Gibco, BRL) at 37°C in a 95% O2–5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells used for transient transfection experiments were grown on 30 mm Petri dishes to 60–70% confluence. Both P2X4 and P2X7 receptors used in this work were originally cloned from mouse parotid glands (here referred to as mP2X4R and mP2X7R, respectively) and inserted in a bicistronic vector for expression in mammalian cell lines (see Reyes et al. 2008, for cloning description). HEK cells were transfected with vectors (1 μg μl−1) pIRES2-EGFP-P2X7R or pIRES2-EGFP-P2X4R using the Polyfect transfection Reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. For experiments with cells co-expressing mP2X4R and mP2X7R, cells were transfected with 2 μg cDNA in different ratios. The ratios indicate the proportional amount of each cDNA used in transfection. After 24 h of transfection, cells were detached using trypsin, replated onto 5 mm glass coverslips and allowed to attach for at least 3–5 h before use. Alternatively, stably transfected HEK cells with mP2X7R were used. Briefly, HEK cells were grown on 30 mm Petri dishes to 80% confluence and transfected with pIRES2-EGFP-P2X7R (1 μg μl−1) using the Polyfect transfection Reagent as usual (Qiagen). Selection was accomplished with 0.45 mg ml−1 of geneticin (Gibco BRL) added 24 h after transfection. Cell growth was monitored every 2 days and medium containing geneticin was changed every week. After 2–4 weeks, single fluorescent colonies containing stably transfected cells began to appear. These colonies were collected and maintained in DMEM + 10% FBS + geneticin (0.45 mg ml−1).

Electrophysiological recordings

Isolated mouse parotid acinar cells or transfected HEK cells were placed in a recording chamber mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Eclipse TE2000-S Nikon, Melville, NY, USA) equipped with UV illumination (X-Cite120, EXFO, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) fluorescence observed under blue light (∼488 nm) illumination was used to identify successfully transfected HEK-293 cells. Whole cell currents were recorded at room temperature (20–22°C) using the patch clamp technique (Hamill et al. 1981) with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Currents were sampled and filtered at 1 kHz using the pCLAMP software v8 (Molecular Devices). Patch pipettes (Corning 8161, Warner Instruments, LLC, Hamden, CT, USA) had resistances of 3.5–5 MΩ when filled with the standard pipette (internal) solution containing (in mm): TEACl or NaCl 140, EGTA 20 and Hepes 20 (pH 7.3; tonicity ∼335 mosmol kg−1). Cells were bathed in a standard external solution containing (in mm): TEACl or NaCl 140, CaCl2 0.5, d-mannitol 100 and Hepes 20 (pH 7.3; tonicity ∼380 mosmol kg−1). ATP (di-Tris salt) was added to the external solution at the desired concentrations and the pH was readjusted to 7.3 with TEAOH or NaOH. Solutions were gravity-perfused into the recording chamber at a flow rate of ∼4 ml min−1. A 3 m KCl agar bridge was used to ground the recording chamber. Liquid junction potentials were not determined but were assumed to be small due to the use of external and internal solutions with symmetrical TEACl or NaCl concentrations, and therefore membrane voltages were not corrected.

To determine the kinetics of the ATP-activated current resulting from expression of different constructs, cells were held at 0 mV for 4 s and then stepped to −80 mV for 1 min and then back to 0 mV. ATP was applied for 30 s when the cell was at −80 mV. Ivermectin (IVM) effects were determined from a time course of the current amplitude recorded by pulsing the membrane to −80 mV for 150 ms every 2.5 s. Receptor channels were activated by different [ATP] applied after a 1.5 min pre-incubation period with 3 μm IVM. IVM exposure was flanked by applications of ATP alone. Internal and external solutions used in these experiments contained 140 mm NaCl.

Concentration–response curves for mP2X7R were constructed by applying increasing [ATP]. For cells expressing mP2X4R or mP2X7R–mP2X4R as well as for fresh isolated acinar cells, the concentration–response curves were constructed by applying a low [ATP] followed by a 5 min wash period and a final application of 5 mm ATP. In both cases, the fractional response was calculated relative to the response elicited by 5 mm ATP. In either case, the current was monitored by pulsing the membrane to −80 mV for 150 ms every 2.5 s or by continuously holding the cells at −80 mV.

Ethidium bromide uptake assay

Ethidium bromide uptake was elicited by stimulation with 150 μm Bz-ATP. The uptake was determined by measuring whole cell fluorescence (in arbitrary units of fluorescence, auf) using a Hamamatsu camera attached to an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Nikon TE2000, Melville, NY, USA) with a 40× fluorescence objective (Reyes et al., 2009). Fluorescence was measured at 544/610 nm excitation/emission using the Imaging Workbench software (INDEC Biosystems, Santa Clara, CA, USA). HEK-293 cells transfected with mP2X7R, mP2X4R and mP2X4R:mP2X7R (2 : 1 ratio) cDNA were bathed in a physiological solution (pH 7.3) containing (in mm): NaCl 150, Hepes 10, glucose 13, KCl 2 and 0.00127 ethidium bromide (a cell impermeant dye). Images were collected during 15 min every 5 s, before (2 min) and after (13 min) stimulation with Bz-ATP. Background fluorescence was subtracted to obtain the Bz-ATP (or ATP)-induced fluorescence as a function of time. Time courses for dye uptake were fitted with a mono-exponential function (eqn (1)) and a time constant (τ) for the uptake process was obtained for each of the different groups.

Data analysis

Whole cell currents measured at −80 mV during long lasting ATP applications were normalized to the peak current value. For normalization purposes, the time needed to reach peak amplitude was redefined as t= 0 s. We refer to the kinetics of the current during ATP application as decay of ATP-activated current (note that this decay is different from channel deactivation which happens upon ATP wash). Current decay was analysed using either a mono- or a bi-exponential equation (eqns (1) and (2)):

| (1) |

| (2) |

where y0 is the maximum decay at steady state (fraction of residual current) and τ1 and τ2 are time constants of decay. Activation time constants (τact) were determined by fitting a mono-exponential function to the onset phase of the ATP-activated current. The statistical significance of data differences was tested using one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05) and Dunnett's post hoc test between groups taking the mP2X7R current kinetics alone as a control. Current enhancement induced by IVM was computed as the current in the presence of IVM divided by control current both activated by the same ATP concentration (IIVM+ATP/IATP). ATP-induced Na+ currents before and after IVM application were also compared using Student's t-test for paired data, and P < 0.05 was taken to indicate significance. Data are presented as means ±s.e.m. and n indicates the number of cells tested.

Materials

ATP (di-Tris salt), Bz-ATP, IVM and all other reagents were purchase from Sigma Chemical Co. Fresh ATP solutions were prepared daily in TEACl or NaCl containing solutions. IVM solutions were prepared fresh before every experiment. IVM was dissolved in DMSO and the stocks were kept at −4°C for 2 weeks and then discarded.

Results

In previous work we demonstrated that in the absence of external Na+, fresh isolated acinar cells from mouse salivary glands stimulated with 5 mm ATP show novel ion permeability and that such permeability can be attributed mainly to activation of mP2X7R (Arreola & Melvin, 2003; Reyes et al. 2008). However, in acinar cells P2X4Rs are also present but their contribution to the ATP-generated current is not clear. Here we investigated whether or not both receptors shape the acinar cell response to ATP by comparing the response to external ATP in isolated acinar cells vs. HEK-293 cells co-expressing these receptor types.

Time course of ATP-activated current in acinar cells versus HEK-293 cells

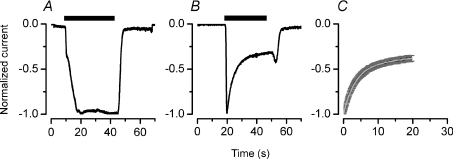

The ATP-activated current was recorded from fresh isolated mouse acinar cells bathed and dialysed with either 140 mm Na+ or 140 mm TEA+ and stimulated with 5 mm ATP. Figure 1A shows an example (n= 8) of the current recorded from a cell in Na+-containing solutions. The ATP-activated current showed a biphasic onset but remained fully sustained during the ATP application. Time to reach the first and second phase was 1.5 ± 0.1 and 9 ± 0.6 s, respectively. In contrast, in TEA+ the ATP-activated current (Fig. 1B) quickly reached a peak and then decayed (even in the presence of ATP) to a plateau. A kinetic analysis of the current generated by the receptors was performed by quantifying the rate of current decay in the presence of ATP. This decay phase of the TEA+ current was fitted with a bi-exponential function (eqn (2)). Figure 1C shows the average of the normalized current and its fit (white line). Two time constants τ1= 2.1 ± 0.2 s and τ2= 8.1 ± 1.4 s were obtained. The fraction of the TEA+ current that remained at steady state (y0) was estimated to be −0.4 ± 0.03 (n= 6).

Figure 1. Currents induced by external ATP in acinar cells.

A, representative whole-cell current carried by Na+ (n= 8) and recorded at −80 mV from a fresh isolated acinar cell. Channels were activated by perfusing 5 mm ATP during the indicated time (black bar). Current was normalized to maximum peak value. B, representative current recorded from a cell dialysed and bathed in TEA+-containing solutions and stimulated with 5 mm ATP. C, normalized peak current was shifted to t= 0, averaged and then fitted with a bi-exponential function (continuous white line) to calculate decay time constants (τ1 and τ2) and maximum current decay at steady-state (y0). Black and dark grey lines are mean and s.e.m. values (n= 6), respectively. Cells were dialysed and bathed with TEA+-containing solutions.

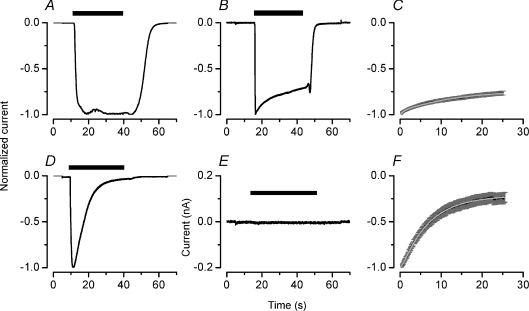

The current induced by long lasting ATP applications to heterologously expressed rat P2X7 and P2X4 receptors display sustained and transient time courses, respectively (North, 2002). Our data show that in the presence of Na+ the ATP-activated current recorded in acinar cells is sustained during the entire ATP application, suggesting that most of the current was generated by mP2X7R alone. This also suggests that the contribution of mP2X4R to the total current is either small or non-existent. If this was the case then the response to external ATP in the presence of TEA+ had to be dominated by mP2X7R. In order to determine the contribution of each receptor to the ATP response in acinar cells, we recorded the ATP-activated current from HEK cells expressing each receptor separately. We started by recording the ATP-activated current elicited with 5 mm ATP in cells expressing mP2X7R alone bathed and dialysed in Na+-containing solutions. Figure 2A shows that this was a sustained current with slow onset kinetics. In contrast, when cells were bathed and dialysed in TEA+-containing solutions, the current activated by 5 mm ATP reached a peak in less than 0.2 s and slowly decayed during the period of ATP application (Fig. 2B). The kinetic analysis of the mono-exponential decay phase in the mP2X7R current gave τ1= 18 ± 4 s and y0=−0.7 ± 0.03 (n= 15) (Fig. 2C). Conversely, when mP2X4R was expressed alone and 5 mm ATP was used to activate the current in cells bathed and dialysed with solutions containing Na+, a rapidly activating and deactivating current was recorded (Fig. 2D). To our surprise, when 5 mm ATP and TEA+-containing solutions were used, no currents through mP2X4R could be recorded at −80 mV (Fig. 2E) or at any other voltage (data not shown). To confirm that the lack of currents was not due to an ultra-rapid desensitization produced by the high [ATP] used or to a deficient surface expression of mP2X4R, we first exposed the cells to a TEA+-containing external solution and then superfused them with a solution containing Na+. This entire manoeuvre was done in the presence of 5 mm ATP. When TEA+ was replaced with Na+ a small residual current could be seen (data not shown). On average and after 20 s of ATP application we recorded –70 ± 10 pA (n= 9) of residual current. Thus, the mP2X4R channels reached the plasma membrane and were indeed functional but not permeable to TEA+.

Figure 2. Whole cell current generated by mP2X7R (upper row) and mP2X4R (lower row) expressed in HEK-293 cells.

A and B, current recorded from two different cells expressing mP2X7 receptors dialysed and bathed in solutions containing Na+ (A) or TEA+ (B). Note the absence of a decay phase for the Na+ current (n= 7). C, average decay phase of TEA+ currents (n= 15) was fitted with a mono-exponential function. Black and grey lines are mean and s.e.m. values, respectively. D and E, current recorded from two different cells expressing mP2X4R alone dialysed and bathed with solutions containing Na+ (D; representative of n= 8) or TEA (E, representative of n= 13). F, average decay phase of Na+ current through P2X4R (n= 8). Continuous line (shown in white) is the fit with a mono-exponential function to estimate the time constant (τ1) and maximum decay (y0). Black bars above the traces indicate the duration of 5 mm ATP application. Currents were recorded at −80 mV.

A kinetic analysis of the current generated in the presence of Na+ by mP2X4R was performed by quantifying the rate of current decay in the presence of ATP. Figure 2F shows the normalized mP2X4R current and the fit to the decay phase with a mono-exponential equation (eqn (1)) that gave a time constant τ1= 7.7 ± 0.6 s and y0=−0.2 ± 0.05 (n= 8). In Table 1 activation time constants (τact) obtained for P2X receptors expressed alone or in combination in HEK cells are compared to τact values obtained using freshly dissociated acinar cells. All cells were bathed and dialysed with solutions containing either Na+ or TEA+ and τact values for the ATP-activated currents at −80 mV are listed.

Table 1.

Amplitude and activation time constants of currents generated by mP2X receptors

| Receptor combination | Itotal (nA) | τact (s) | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| P2X4 (Na+ and Ca2+) | −1.9 ± 0.6 | 0.3 ± 0.03 | 8 |

| P2X7 (Na+ and Ca2+) | −7.3 ± 0.5 | ND | 5 |

| P2X7 (Na+ and Ca2+)** | −7.5 ± 1.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 7 |

| P2X7 (TEA+ and Ca2+) | −1.7 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 15 |

| P2X4/P2X7 2 : 1 (Na+ and Ca2+) | −2.8 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 8 |

| P2X4/P2X7 2 : 1 (TEA+ and Ca2+) | −1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 10 |

| P2X4/P2X7 1 : 1 (TEA+ and Ca2+) | −1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 10 |

| P2X4/P2X7 1 : 2 (TEA+ and Ca2+) | −2 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 8 |

| Acinar cells (TEA+ and Ca2+) | −0.5 ± 0.04 | 0.2 ± 0.03 | 6 |

| Acinar cells (Na+ and Ca2+) | Phase 1 =−1.4 ± 0.2 | ||

| Phase 2 =−2.8 ± 0.4 | — | 8 | |

| P2X7 (TEA+ and 0 Ca2+)** | −4.6 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 6 |

| P2X7 (TEA+, Ca2+ and 1 mm CBX)** | −5.1 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.04 | 6 |

HEK-293 and acinar cells were dialysed with standard intracellular solution and bathed with extracellular solutions containing either Na+ or TEA+. External solutions had either 0.5 mm or 0 mm CaCl2. Most of the experiments were performed using HEK-293 cells transiently transfected (** indicates stable transfection). Activation time constants were obtained from fitting the onset phase of the current that developed upon external ATP application. Vm=−80 mV. Main cations in the external solution are indicated in parenthesis. ND = not determined.

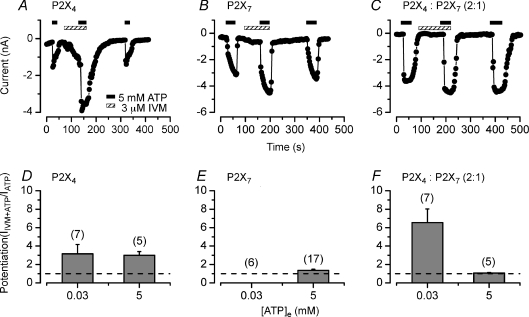

Time constant values obtained for control experiments are included to show that differences in current kinetics are not due to the presence of Ca2+ or pannexin-1 activation. Pannexin-1 (panx-1) is an endogenous protein present in HEK cells, which has been reported to couple to P2X7R in order to open large pores that allow passage of dye molecules of up to 900 Da (Pelegrin & Surprenant, 2006; Reyes et al. 2009). We know panx-1 is activated under our experimental conditions (Fig. 4) so we question whether activation of panx-1 could change the kinetics of the ATP-activated current. To rule out this possibility we used 1 mm carbenoxolone, a panx-1 inhibitor (Pelegrin & Surprenant, 2006). Results show that the current decay parameters of the ATP-activated current were not altered by carbenoxolone application in cells expressing mP2X7R (y0=−0.7 ± 0.03 and τ1= 13.3 ± 1 s).

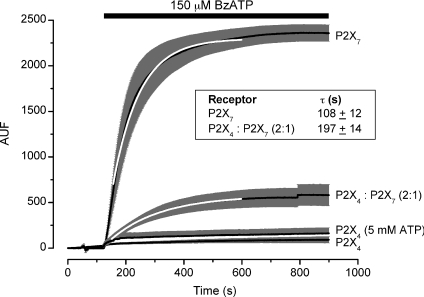

Figure 4. Ethidium bromide uptake in HEK-293 cells expressing P2X receptors.

HEK cells were transfected with mP2X4R, mP2X7R or mP2X4R:mP2X7R (2 : 1 ratio). Ethidium bromide (1.27 μm) was added to the Na+-containing bath solution and was present throughout the experiment. Cells were stimulated with 150 μm Bz-ATP during the indicated time. Fluorescence images were taken every 5 s. Time course of ethidium uptake (reported in arbitrary units) in cells expressing mP2X7R (n= 30), mP2X4R (n= 34) or mP2X4R:mP2X7R (n= 14). Time course was fitted with a mono-exponential function (white line) and time constants were calculated. Note that the presence of mP2X4R slowed down the uptake observed with mP2X7R alone. In addition to Bz-ATP, 5 mm ATP was used on mP2X4R, but no ethidium bromide uptake was induced in either case (n= 22). Black lines are data points and dark grey bars are s.e.m. values. Inset table shows time constant values obtained from each dye uptake time course.

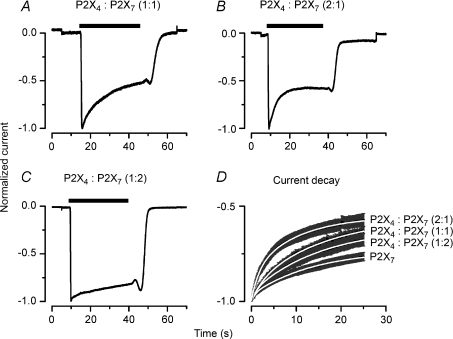

mP2X7R current kinetics are changed in the presence of mP2X4R

Since heterologous expression of either mP2X4 or mP2X7 receptors did not reproduce the current recorded in acinar cells we then co-expressed both receptors using 0 : 1, 1 : 1, 1 : 2 and 2 : 1 (P2X4 : P2X7) cDNA ratios to examine changes in current kinetics which may indicate possible functional interactions between these receptors. In these experiments, we focused our analysis on the rate of current decay seen in TEA+-containing solutions when ATP was present. If mP2X7R homotrimers are assembled we expect to see only mP2X7R-like currents (see Fig. 2B) because under these ionic conditions activation of mP2X4R generates no current. However, in cells transfected with a 1 : 1 cDNA ratio the current decayed even more (Fig. 3A) than with mP2X7R alone (Fig. 2B). In cells transfected with a 1 : 1 ratio, y0 was −0.5 ± 0.03 (n= 10). In addition, the time course of the current decay was no longer mono-exponential, it was bi-exponential (Fig. 3D) with τ1= 2.2 ± 0.4 s and τ2= 20 ± 3 s (n= 10). The presence of a faster component in the current decay indicated to us that mP2X4R somehow accelerate the decay of the TEA+ current generated by mP2X7R. A difficulty with co-expression experiments is the unknown amount of receptor protein that reaches the plasma membrane, and thus we questioned the significance of this finding. To corroborate our results we then co-expressed both receptors at three additional cDNA ratios. Figure 3B shows the normalized current obtained from a cell transfected with a 2 : 1 cDNA (P2X4 : P2X7) ratio. In this case the current quickly activated and showed an even faster decay than the currents obtained from cells expressing 1 : 1 mP2X4R : mP2X7R or mP2X7R alone. The time course of the current decay (Fig. 3D) was fitted with a bi-exponential equation with time constants τ1= 2 ± 0.4 s and τ2= 14.2 ± 3.5 s and y0=−0.5 ± 0.04 (n= 10). ATP-activated current from cells transfected with 1 : 2 ratio bear a closer resemblance to currents from cells expressing mP2X7R alone (τ1= 20.6 ± 4.9 s, n= 8), with y0=−0.6 ± 0.04 (n= 8) (Fig. 3C, D). Finally, estimates of the current remaining at the steady state (y0) for each co-expression (1 : 1, 2 : 1 and 1 : 2 ratio) were significantly different from that of mP2X7R (Fig. 3D). These comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05) and Dunnett's post hoc test. Note that the onset values of ATP-activated current were not statistically different (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test, P < 0.05) in cells transfected with 0 : 1, 1 : 1, 1 : 2 and 2 : 1 cDNA ratios; however, total current was larger in cells transfected with 1 : 2 cDNA ratio compared to 2 : 1 or 1 : 1 (see Table 1). These differences were statistically significant.

Figure 3. Co-expression of mP2X4R with mP2X7R accelerates the decay phase of the ATP-activated TEA+ current.

A–C, representative whole-cell currents recorded from cells transfected with mP2X4R : mP2X7R in 1 : 1 ratio (A), 2 : 1 ratio (B) and 1 : 2 ratio (C) (n= 10, 10 and 8, respectively). Currents were recorded at −80 mV from cells dialysed and bathed with TEA+-containing solutions, exposed to 5 mm ATP during the indicated time (black bar). D, the average decay phase at each condition was plotted and compared to mP2X7R currents (Fig. 2C). Note that current kinetics become faster by increasing the ratio of mP2X4R : mP2X7R cDNA from 1 : 1 to 2 : 1 and the latter looks more similar to the current recorded from acinar cells (Fig. 1B). Kinetic parameters at each ratio were compared to parameters for mP2X7R. Statistically significant differences were obtained at all cDNA ratios (P < 0.05).

mP2X4Rs modulate the ethidium bromide uptake induced by mP2X7R activation

Results presented in Figs 1, 2 and 3 demonstrate that non-conducting mP2X4R (in TEA+-containing solutions) modify mP2X7R TEA+ current kinetics, suggesting that these receptors are able to communicate. As mentioned above, a reported feature of P2X7R is their ability to couple to other proteins such as panx-1, a protein that forms a pore permeable to large molecules such as ethidium bromide (Kim et al. 2001; Pelegrin & Surprenant, 2006; Reyes et al. 2009). We speculated that the interaction between mP2X4R and mP2X7R might also change coupling between P2X7R and panx-1. Thus, we next measured the rate of ethidium bromide uptake as an index of panx-1 activation in HEK cells expressing mP2X4R (transient transfection), mP2X7R (stable transfection) and mP2X4R : mP2X7R (transient transfection with 2 : 1 ratio). Figure 4 shows the time course of ethidium bromide uptake induced by stimulation with 150 μm Bz-ATP. We opted for Bz-ATP since it is a relatively more selective agonist for P2X7R and at this concentration is less effective in activating mP2X4R (Guo et al. 2007). On cells expressing mP2X4R (n= 34), no ethidium bromide uptake was induced by addition of either 150 μm Bz-ATP or 5 mm ATP (Fig. 4, bottom time course) even though ATP at this concentration fully activates the mP2X4 receptor (see Figs 2D and 5B). In contrast, when cells expressing mP2X7R alone (stable transfection) were stimulated with Bz-ATP, a rapid and robust ethidium uptake was induced (approximately ∼2250 auf). Similarly, cells co-expressing both receptors showed dye uptake; however, the extent of this uptake was smaller (uptake decreased by a factor of 4) and slower than that of cells expressing only mP2X7R. Time courses of ethidium uptake were fitted with a mono-exponential function. The time constants determined for mP2X7R alone (n= 30) and 2 : 1 mP2X4R : mP2X7R (n= 14) were 108 ± 12 s and 197 ± 14 s, respectively. Differences between these time constants were statistically significant when evaluated by a non-paired t-test. Similarly, in another experiment the amplitude of ethidium bromide uptake was decreased by a factor of ∼6, in cells transiently transfected with mP2X7R (1377 ± 173 auf, n= 12) or 2 : 1 mP2X4R : mP2X7R (227 ± 62 auf, n= 14) and stimulated with 5 mm ATP (data not shown). The magnitude of the Na+ current was decreased 2.6-fold in cells transiently expressing mP2X4R : mP2X7R compared to cells either stably or transiently expressing mP2X7R alone (Table 1). Thus, the dye uptake seen with mP2X7R alone was both decreased and slowed down in the presence of mP2X4R.

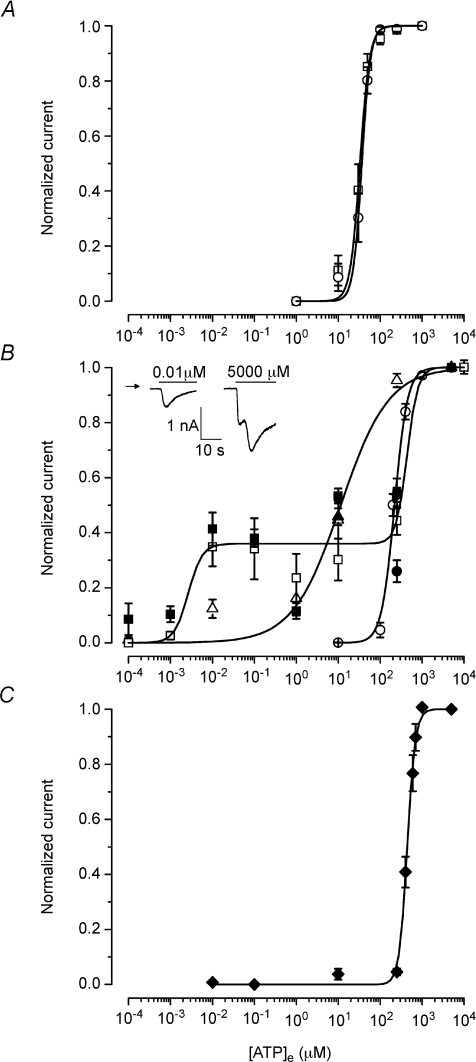

Figure 5. ATP concentration–response curves of salivary gland P2X receptors.

Concentration–response curves for increasing external [ATP] were obtained for mP2X4R alone (triangles), mP2X7R alone (circles) or 2 : 1 mP2X4R : mP2X7R co-expression (squares) as well as for fresh isolated acinar cells (diamonds). Experiments were carried out in cells bathed and dialysed with TEA+ (A) or Na+ (B and C) containing solutions. Open symbols: data obtained by pulsing the cells to −80 mV during 150 ms every 2.5 s. Filled symbols: data obtained by continuously holding the cells at −80 mV. Continuous lines are fits with Hill equation to data obtained using the pulsing method (A and B) or by holding at −80 mV (C). Each data point in C was constructed from data collected from 3–7 different acinar cells. HEK cells expressing mP2X4R or acinar cells were exposed only to two concentrations of ATP (low [ATP] first and then to a saturating concentration of 5 mm) at a time. While HEK cells expressing only mP2X7R were exposed to all ATP concentrations in an increasing fashion. Inset in panel B, examples of current (digitized at 2 kHz) obtained from a representative cell held at −80 mV that was first exposed to 10 nm followed by 5 mm ATP. Continuous lines through data symbols represent fits with the Hill equation to obtain the EC50 values and Hill coefficients shown in Table 2.

Co-expression of mP2X4 and mP2X7 receptors does not change ion permeability but modifies concentration–response curves to ATP

Communication between mP2X4 and mP2X7 receptors could take place either by physical interaction among homotrimeric channels or by way of heterotrimeric channel assembly or by a combination of these two mechanisms. As shown above, mP2X4Rs are permeable to Na+ but not to TEA+ whilst mP2X7R are permeable to both Na+ and TEA+. Also, the ATP sensitivity of both receptors is different. For rat P2X4R the reported EC50 value for ATP is ∼10 μm while for rat P2X7R it is ∼120 μm (Silberberg et al. 2005; Young et al. 2007). Thus, if combinations of (P2X4)2–(P2X7)1 and (P2X4)1–(P2X7)2 subunits assemble into heterotrimeric channels then the resulting channels would have a different cation selectivity and/or ATP sensitivity.

To test for the presence of channels with altered pore properties we determined the permeability ratio TEA+/Na+ (an index of how easily TEA+ access the pore compared to Na+) in cells transfected with mP2X4 : mP2X7 in a 2 : 1 ratio. Whole-cell recordings were performed using an external solution that contained 70 mm NaCl and 70 mm TEACl, while the internal solution contained 140 mm NaCl. The current was activated by 5 mm ATP and the reversal potential was measured. Reversal potential values were −10.5 ± 0.6 mV for mP2X7R (n= 4) and −11.3 ± 1.1 mV for a 2 : 1 mP2X4R:mP2X7R ratio (n= 4). These values are not significantly different, which indicates no changes in ion permeability in cells expressing either mP2X7R or mP2X4:mP2x7.

We then looked for changes in ATP sensitivity in cells expressing different combinations of P2X receptors. To assay changes in ATP sensitivity, concentration–response curves were constructed for heterologously expressed mP2X4R, mP2X7R and mP2X4R:mP2X7R co-expressions. In Fig. 5A, concentration–response curves obtained using TEA+-containing solutions for mP2X7 channels alone as well as for mP2X4:mP2x7 channels (transfection with 2 : 1 cDNA ratio) are shown. From their fit with the Hill equation we estimated EC50 values of 37 μm for mP2X7R and 33 μm for mP2X4R:mP2X7R, showing that in TEA+ there was no change in ATP sensitivity when the channels are expressed separately or in combination. Figure 5B illustrates concentration–response curves for mP2X4R alone (triangles), mP2X7R alone (circles) and mP2X4R:mP2X7R (squares; transfection ratio 2 : 1) obtained using Na+-containing solutions. Complete concentration–response curves were obtained for all constructs by pulsing the cells at −80 mV every 2.5 s (open symbols). The estimated EC50 and Hill coefficient values were 11 μm and 0.8 for mP2X4R and 221 μm and 2.8 for mP2X7R when expressed separately. Filled triangles represent data obtained from cells expressing mP2X4R that were continuously held at −80 mV and exposed to 11 μm ATP. The response was nearly identical to that obtained pulsing the cells to −80 mV. The concentration–response curve obtained using co-transfected cells was rather complex (Fig. 5B; open squares). First, an increase in ATP-activated current was observed in the nanomolar range which plateaued between 0.01 and 0.1 μm ATP. Then a second increase in current was observed in the range of 10–10 000 μm ATP. Data fitting (continuous line) gave a first EC50 of ∼3 nm with a Hill coefficient of 2.7 and a second EC50 of 434 μm with a Hill coefficient of 3.4. Similar results were obtained by continuously holding the cells at −80 mV and then applying the desired [ATP] (filled squares). An example of the currents generated after addition of 10 nm or 5 mm ATP is shown in the inset of Fig. 5B.

The concentration–response curve for co-transfected cells cannot be explained by the contribution of two independent receptor populations such as mP2X4R and mP2X7R (EC50= 11 and 221 μm, respectively). Channels that display high ATP sensitivity may represent assembly of heteromeric channels in HEK-293 cells. To find out if a similar population of receptors was present in acinar cells, a concentration–response curve to ATP was also constructed. Fresh dissociated acinar cells were dialysed and bathed in solutions containing 140 mm Na+. Under this condition the ATP response displayed a slow onset (not shown), and consequently ATP was superfused for more than 180 s (low dose) to ensure steady-state conditions. After the first ATP dose a second 5 mm ATP application followed and this was considered 100% of the response. Figure 5C shows the resulting concentration–response curve obtained at −80 mV. The estimated EC50 and Hill coefficient values were 442 μm and 4.5, respectively. However, unlike the expression system, we did not observe a channel population with high ATP sensitivity in freshly isolated acinar cells. Table 2 summarizes the ATP sensitivity and Hill coefficient obtained for HEK and acinar cells under TEA+ or Na+ conditions. Note that the ATP EC50 value in acinar cells was similar to that obtained in HEK cells co-transfected with P2X4 and P2X7 receptors but twice as big as that obtained in HEK cells expressing only mP2X7R. Best-fit EC50 values were statistically different using a two-tailed t-test (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

ATP sensitivity of currents

| Receptor combination | EC50 (μm) | nHill | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| P2X7 (TEA+ and Ca2+) | 36.6 | 4.3 | 6 |

| P2X4/P2X7 2 : 1 (TEA+ and Ca2+) | 32.9 | 3.7 | 6 |

| P2X4 (Na+ and Ca2+) | 11.5 | 0.8 | 4–6 |

| P2X7 (Na+ and Ca2+) | 220.6 | 2.8 | 4–7 |

| P2X4/P2X7 2 : 1 (Na+ and Ca2+) | 0.003 | 2.7 | 3–9 |

| 434.5 | 3.4 | ||

| Acinar cells (Na+ and Ca2+) | 442.4 | 4.5 | 3–7 |

Different constructs were expressed in HEK cells and acinar cells were freshly isolated. Experiments were carried out using external and internal solutions containing either TEA+ or Na+. EC50 values and Hill coefficients were estimated from fits to data as shown in Fig. 5. All responses were normalized to the maximal response obtained with 5 mm ATP.

Potentiation of ATP-activated Na+ currents by ivermectin

Our results from kinetic analysis, ethidium bromide uptake and ATP sensitivity indicated a possible interaction between mP2X4 and mP2X7 receptors. To further explore this interaction, the response of P2X receptors to ivermectin (IVM) was analysed. IVM works as an allosteric modulator of P2X4R but not of P2X7R (Khakh et al. 1999). It increases the open probability at all [ATP], which results in an increased maximum response (Silberberg et al. 2007).

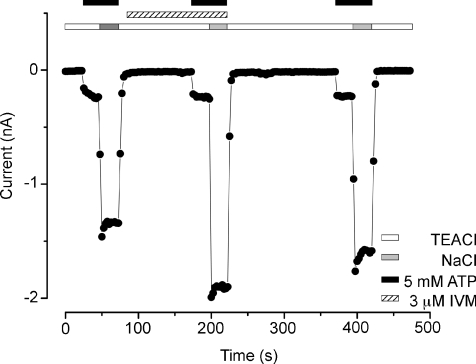

Figure 6 shows a representative (n= 7) time course of current recorded at −80 mV in the absence and presence of IVM. Data are from a representative HEK cell dialysed and bathed in TEA+-containing solutions. ATP at 5 mm was applied to activate the TEA+ current and then the external solution was changed to a solution containing Na+. This was followed by a 20 s wash period and incubation with 3 μm IVM (1.5 min) prior to a second ATP application. In the absence and presence of IVM the TEA+ current was nearly the same (IIVM+ATP/IATP= 0.9 ± 0.05), but to our surprise the Na+ current was larger in the presence of IVM (IIVM+ATP/IATP= 1.2 ± 0.1). Thus, our data show that mP2X7Rs are also slightly potentiated by IVM although their potentiation was strongly dependent on the permeant cation.

Figure 6. IVM potentiates Na+ currents induced by ATP in mP2X7R.

Time course was constructed using currents measured at −80 mV before, during IVM (3 μm) application (hatched bars) and after IVM wash. Cells were dialysed with solutions containing TEA+. mP2X7 receptors were activated by applying 5 mm ATP (black bars) in TEA+ (white bar) or Na+ (grey bar) solutions. In the presence of TEA+ the current in the absence and presence of IVM was nearly the same but when Na+ was used the current in the presence of IVM was larger (n= 7).

Moreover, Fig. 7A and D shows that in Na+ containing solutions 3 μm IVM potentiated the mP2X4R currents (IIVM+ATP/IATP= 3 ± 0.4) as expected. Comparatively, the potentiation observed for the mP2X7R current was small but statistically significant (IIVM+ATP/IATP= 1.4 ± 0.1, Fig. 7B and E).

Figure 7. Regulation of P2X receptors by ivermectin.

A–C, time courses were constructed using currents measured at −80 mV before, during IVM (3 μm) application (hatched bars) and after IVM wash. Receptors were activated by applying 5 mm ATP (black bars). Cells were dialysed and bathed with solutions containing 140 mm NaCl. A, potentiation of mP2X4R currents. B, potentiation of mP2X7R currents. C, lack of potentiation in cells transfected with mP2X4R : mP2X7R in 2 : 1 ratio. D–F, summary of IVM effect on Na+ currents. D, IVM enhanced current carried by Na+ through mP2X4R equally when the receptors were activated by either 0.03 or 5 mm ATP. E, potentiation by IVM of the current induced by 5 mm ATP but not with 0.03 mm ATP in cells expressing mP2X7R. F, IVM did not enhance the current (activated with 5 mm ATP) in cells co-transfected with mP2X4 : mP2X7 receptors using a 2 : 1 cDNA ratio but did so when 0.03 mm ATP was used. Dash lines indicate NO potentiation. Number of cells tested is indicated above each bar.

A striking finding was the lack of noticeable potentiation on the current activated by 5 mm ATP (Fig. 7C and F) in cells co-expressing mP2X4R : mP2X7R in a 2 : 1 ratio (the same was observed in a 1 : 1 ratio; data not shown) even though IVM potentiated the response of mP2X4 and mP2X7 receptors separately. Current ratios (IIVM+ATP/IATP) were 1.1 ± 0.05 (Fig. 7F) and 1.2 ± 0.1 in cells transfected with 2 : 1 and 1 : 1 cDNA ratios, respectively. Because the ATP sensitivity of mP2X4R is higher than that of mP2X7R and certainly 5 mm ATP induces full activation and deactivation of mP2X4R (see Figs 2D and 5) we were concerned that the lack of potentiation was due to mP2X4R desensitization. Thus, to rule out these effects we tested IVM on currents activated with 0.03 mm[ATP], a concentration that activates ∼70% of mP2X4R and none of the mP2X7R. At this [ATP] IVM potentiated ∼3.2 times the current generated by mP2X4R (Fig. 7D) but did not induce current in cells expressing mP2X7R alone (Fig. 7E). In contrast, in cells transfected with a 2 : 1 cDNA ratio, IVM potentiated ∼7 times the current activated by 0.03 mm ATP (Fig. 7F). Albeit this tendency suggests that the sensitivity to IVM is higher in cells co-expressing both receptors, no statistical significance between the mP2X4R and the mP2X4R:mP2X7R was found.

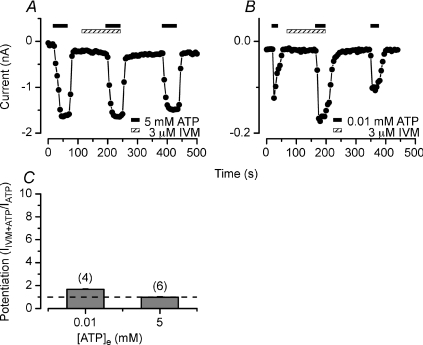

Since IVM did not potentiate the Na+ currents activated by saturating [ATP] in HEK cells co-expressing both receptors, we reasoned that in acinar cells (which naturally express mP2X4R and mP2X7R) the same would occur. Consistent with this idea, IVM failed to enhance the Na+ current activated by 5 mm ATP in fresh isolated parotid acinar cells (1 ± 0.05, Fig. 8A and C). Decreasing the ATP concentration to 0.01 mm resulted in slight but statistically significant potentiation (1.7 ± 0.03, Fig. 8B and C), just as we saw in HEK cells co-expressing both receptors.

Figure 8. Effect of ivermectin on ATP-activated Na+ current from mouse parotid acinar cells.

A and B, time course of current recorded at −80 mV before, during IVM (3 μm) application (hatched bars) and after IVM wash. Receptors were activated by applying (black bars) either 5 mm (A) or 0.01 mm (B) ATP. C, summary of IVM effect on the currents activated by 0.01 and 5 mm ATP, respectively. Note that IVM did not enhance the current activated by 5 mm ATP. Dash line indicates NO potentiation. Number of cells tested is indicated above each bar.

Discussion

In this work we show that heterologous expression of either mP2X4 or mP2X7 receptors do not reproduce all the features of the ATP-activated current recorded in acinar cells unless both receptors are co-expressed. Co-expression of mP2X7R with mP2X4R results in: (1) generation of whole cell currents that resemble the ATP-activated TEA+ current in native mouse parotid acinar cells; (2) slower rate of ethidium bromide uptake than that observed with mP2X7R alone; (3) a channel fraction with lower ATP sensitivity than that of mP2X4R or mP2X7R alone, and (4) lack of potentiation by IVM of Na+ current activated by 5 mm ATP. The latter is also seen in acinar cells. This evidence substantiates a functional interaction between mP2X4 and mP2X7 receptors in parotid acinar cells.

Interaction between mP2X4 and mP2X7 receptors could take place via either assembly of heterotrimeric P2X channels with novel properties or contact between homotrimeric channels or a combination of these mechanisms. Although our data do not allow the precise characterization of heterotrimeric channel formation as the mechanism of interaction, most of our results (concentration–response curves in Na+, IVM effect, TEA+ current kinetics and ethidium bromide uptake) suggest that in native acinar cells and HEK cells mP2X4R and mP2X7R could assemble into heterotrimeric channels with novel functional and pharmacological properties. Assembly of heterotrimeric P2X4/P2X7 channels is also suggested by co-immunoprecipitation of P2X7R with P2X4R in bone marrow derived macrophages (Guo et al. 2007) and by the interaction of P2X7R with a variety of cell membrane anchored proteins (Kim et al. 2001). Nevertheless, physically close homotrimeric channels interacting through protein–protein contacts could also immunoprecipitate together (Murrell-Lagnado & Qureshi, 2008). This has been shown for P2X2 and ρ1/GABA, two completely different receptors that interact with each other (Boué-Grabot et al. 2004).

Our experimental data show that after co-expression the resulting mP2X4–mP2X7 channels display novel pharmacological responses such as a lower ATP sensitivity and altered IVM potentiation. In cells expressing either mP2X7R alone or mP2X4R and mP2X7R, the TEA+ current was activated by ATP with an EC50 of ∼33 μm. In cells expressing mP2X4R or mP2X7R alone the Na+ current was activated with an EC50 of 11 and 221 μm, respectively, values similar to those reported in other tissues (Silberberg et al. 2005; Young et al. 2007). In contrast, in cells co-expressing both channels a quite complex concentration–response curve was obtained in Na+. This curve is not explained by the presence of independent mP2X4R (EC50= 11 μm) and mP2X7R (EC50= 221 μm) populations. Instead our analysis suggests the presence of at least two receptor populations whose EC50 values (∼3 nm and 434 μm, respectively) differed significantly from those of the individual receptors. This observation suggests that in the heterologous expression system, functional channels may include both homo- and hetero-trimers. Assembly of hetero-trimers, either (mP2X4R)2–(mP2X7R)1 or (mP2X4R)1–(mP2X7R)2, could have altered ATP sensitivity. This could be either extremely high ATP affinity (<10 nm) or low ATP affinity (>400 μm). Although the concentration–response curve in the heterologous expression system suggests assembly of hetero-trimeric channels, in native cells we did not observed channels with such high ATP sensitivity. Instead we only observed a single, low ATP sensitivity channel population. This channel population was twice as less sensitive to ATP than mP2X7R channels alone. In addition, we observed that the ATP-activated current in acinar cells had a slower time course than that of mP2X7R or mP2X4R channels. This slower time course of channel activation has been reported by others working in epithelial cells (Li et al. 2005; Ma et al. 2006). A caveat in our experiments is the lack of information about the level of channel expression in the heterologous expression and the acinar cells. Clearly transiently or permanently transfected HEK cells expressed larger currents than acinar cells, indicating that higher protein levels are present in the plasma membrane of HEK cells. If this assumption is correct then higher level of protein expression would result in different levels of homo- and hetero-trimers, which will directly influence the dose–response relations. Thus, if channels with high ATP sensitivity are present in low abundance in the acinar cells, their functional response recorded using macroscopic currents may be compromised. Nevertheless, the fact that the kinetics of the ATP-activated current in acinar cells are slower than that of each P2X receptor and that the EC50 is bigger than that of mP2X7R suggests that in the native cells, P2X receptors generate channels with new pharmacological responses. Another novel pharmacological response observed was IVM potentiation. IVM potentiates homotrimeric P2X4R channels by binding between transmembrane helices near the extracellular side (Silberberg et al. 2007). Our data show that IVM potentiates the Na+ current through mP2X4R as well as through mP2X7R when activated by 5 mm ATP. Remarkably, IVM failed to enhance the Na+ current activated by 5 mm ATP in HEK cells co-transfected with both receptors as well as in acinar cells. Furthermore, the potentiation by IVM of the Na+ current activated by 0.03 mm ATP was larger in cell co-expressing P2X4R and P2X7R channels than in cell expressing only mP2X4R probably due to activation of the high ATP sensitivity channel population seen during co-expression experiments (Fig. 5B). A similar behaviour is observed in acinar cells (Figs 7F and 8C), although the potentiation is not as large. Altogether, these pharmacological observations are incompatible with the expression of two homotrimeric channel populations.

Different functional responses seen in cells expressing mP2X4–mP2X7 channels include changes in current kinetics and ethidium bromide uptake. When mP2X7R is expressed alone the time course of the Na+ currents was sustained as shown by others (Hibell et al. 2000) but in TEA+ the currents displayed a slight decay. This decay was accentuated by co-expressing both receptors despite the fact that mP2X4Rs do not allow passage of TEA+. This indicates that mP2X4Rs modify the current kinetics by interacting with mP2X7Rs to yield channels whose functional response is changed. In acinar cells the TEA+ current displays similar behaviour albeit the EC50 value is larger (Arreola & Melvin, 2003) than the one we report here. The rate of current decay recorded in mP2X4:mP2x7 channels was not altered by complete removal of external Ca2+ or addition of 1 mm carbenoxolone (Pelegrin & Surprenant, 2006). The lack of effect caused by Ca2+ removal was expected since with 0.5 mm CaCl2 in the bath solution, Ca2+ would carry less than 2% of the total current in P2X7 channels (Riedel et al. 2007). Thus, the effects of co-expressing both receptors are not due to altered Ca2+ influx or activation of pannexin-1 hemichannels, but may indeed reflect subunit interaction. Also, the ethidium bromide uptake result hints to a similar conclusion. The dye uptake observed in the mP2X4–mP2X7 co-expression was slower and smaller than the uptake seen with mP2X7 receptors alone. Since ethidium bromide uptake is due to pannexin-1 activation probably by the carboxy-terminus of mP2X7R (Becker et al. 2008), our result suggests that a physical interaction between P2X receptors delays pannexin-1 activation. Alternatively, assembly of heterotrimeric receptors could produce channels that do not activate pannexin-1 as efficiently as mP2X7R alone. Also, we observed that the magnitude of the Na+ current (which is proportional to receptor density) was smaller in cells co-expressing both receptors. Thus, if the rate of ethidium bromide is proportional to receptor density then a decreased receptor density would explain the slower ethidium bromide uptake.

An additional observation to be considered in the data interpretation is the modulatory effect of monovalent cations on the function of mP2X7R. Since single channel recording of rat P2X7R shows that passage of small and large cations occurs through the same pore without changing its diameter (Riedel et al. 2007), we expected to see similar pharmacological and functional responses independently of the ion carrying the current. This is not the case. In this receptor the function of domains such as extracellular binding sites for ATP and blockers, the pore and the intracellular domains that couple the receptor to pannexin-1 are regulated by external Na+ (Reyes et al. 2008; Ma et al. 1999; present study). In the absence of external Na+, several changes are observed: (1) the pore of mP2X7R becomes permeable to Cl− and has a higher SCN− conductivity; (2) cibacron blue potentiates the TEA+ current but blocks the Na+ current through mP2X7R; (3) IVM does not potentiate the TEA+ current but potentiates the Na+ current; (4) the TEA+ current decays in the presence of ATP but the Na+ current does not; (5) the ATP sensitivity of mP2X7R is higher in the presence of TEA+; (6) P2X7Rs couple better to pannexin-1 in the presence of TEA+ (Reyes et al. 2008; Virginio et al. 1999; present study); and (7) P2X7R displays low open probability and fast deactivation when Na+ is present (Riedel et al. 2007). In summary, the function of P2X7R is strongly dependent on external Na+ and such Na+ dependence could be passed on to channels formed by co-expressing both receptors. Although the precise mechanism by which Na+ regulates these myriad of P2X7R functions remains to be determined, we hypothesized in a previous report that the mP2X7R could undergo conformational changes when Na+ is removed from the external medium thereby resulting in channels with a different structure but still activated by external ATP (Reyes et al. 2008). If the external Na+ is essential to maintain the structure of the receptor then its ability to interact and respond to activators and regulators may become altered and/or compromised in the absence of Na+. This hypothesis may in part explain our data, but more biochemical and structural data are needed to test this idea.

In conclusion, our data indicate that a functional interaction between mP2X7 and mP2X4 receptors takes place in epithelial cells from salivary glands. This functional interaction could be important in generating the ATP-activated current and shaping subsequent physiological responses to ATP signalling. Such functional interaction may also be in place in other cells that naturally co-express these receptors such as airway ciliated cells, macrophages and hepatocytes (Ma et al. 1999, 2006; Gonzales et al. 2007; Guo et al. 2007; Raouf et al. 2007).

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Carmen Y. Hernandez-Carballo for excellent technical assistance. This research was supported by grants from CONACyT (59889 and 79897 to J.A. and 45895 to P.P.C.) and NIH (PO1-HL18208 to R.E.W. and J.A.). G.C.-P. and G.P.-F. were supported by fellowships from CONACYT (181285 and 201794).

Author contributions

JA and PPC contributed to conception and design. All authors contributed to analisis and data interpretation, wrote and critically revised the manuscript and approval of the final version. GCP performed most of the experiments. JPR performed ATP concentration–response curves in TEA solutions. GPF carried out the ethidium bromide assay. Experiments were conducted at the School of Medicine and Institute of Physics of UASLP.

References

- Arreola J, Melvin JE, Begenisich T. Volume-activated chloride channels in rat parotid acinar cells. J Physiol. 1995;484:677–687. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola J, Melvin JE. A novel chloride conductance activated by extracellular ATP in mouse parotid acinar cells. J Physiol. 2003;547:197–208. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.028373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D, Woltersdorf R, Boldt W, Schmitz S, Braam U, Schmalzing G, Markwardt F. The P2X7 carboxyl tail is a regulatory module of P2X7 receptor channel activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25725–25734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boué-Grabot E, Toulmé E, Emerit MB, Garret M. Subunit-specific coupling between γ-aminobutyric acid type A and P2X2 receptor channels. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52517–52525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bours MJ, Swennen EL, Di Virgilio F, Cronstein BN, Dagnelie PC. Adenosine 5′-triphosphate and adenosine as endogenous signaling molecules in immunity and inflammation. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112:358–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SG, Townsend-Nicholson A, Jacobson KA, Burnstock G, King BF. Heteromultimeric P2X(1/2) receptors show a novel sensitivity to extracellular pH. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:673–680. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.2.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Purine and pyrimidine receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1471–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6497-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas-Pruneda G, Reyes JP, Pérez-Cornejo P, Arreola J. Functional cross-regulation of murine salivary gland P2X4 and P2X7 receptors. Biophys J. 2007 2145-Pos. [Google Scholar]

- Casas-Pruneda G, Reyes JP, Pérez-Cornejo P, Arreola J. Interaction between P2X4 and P2X7 receptors modulates ivermectin effect. Biophys J. 2008 1313-Pos. [Google Scholar]

- Chessell IP, Hatcher JP, Bountra C, Michel AD, Hughes JP, Green P, Egerton J, Murfin M, Richardson J, Peck WL, Grahames CB, Casula MA, Yiangou Y, Birch R, Anand P, Buell GN. Disruption of the P2X7 purinoceptor gene abolishes chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Pain. 2005;114:386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Blocking IL-1 in systemic inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1355–1359. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales E, Prigent S, Abou-Lovergne A, Boucherie S, Tordjmann T, Jacquemin E, Combettes L. Rat hepatocytes express functional P2X receptors. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3260–3266. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C, Masin M, Qureshi OS, Murrell-Lagnado RD. Evidence for functional P2X4/P2X7 heteromeric receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1447–1456. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.035980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for highresolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibell AD, Kidd EJ, Chessell IP, Humphrey PPA, Michel AD. Apparent species differences in the kinetic properties of P2X7 receptors. Brit J Pharmacol. 2000;130:167–173. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS, Proctor WR, Dunwiddie TV, Labarca C, Lester HA. Allosteric control of gating and kinetics at P2X4 receptor channels. J Neurosci. 1999;19:289–299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07289.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Jiang LH, Wilson HL, North RA, Surprenant A. Proteomic and functional evidence for a P2X7 receptor signalling complex. EMBO J. 2001;20:6347–6358. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BF, Townsend-Nicholson A, Wildman SS, Thomas T, Spyer KM, Burnstock G. Coexpression of rat P2X2 and P2X6 subunits in Xenopus oocytes. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4871–4877. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-04871.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê KT, Babinski K, Séguéla P. Central P2X4 and P2X6 channel subunits coassemble into a novel heteromeric ATP receptor. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7152–7159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07152.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, Neidhart S, Holy C, North RA, Buell G, Surprenant A. Coexpression of P2X2 and P2X3 receptor subunits can account for ATP-gated currents in sensory neurons. Nature. 1995;377:432–435. doi: 10.1038/377432a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Luo X, Muallem S. Regulation of the P2X7 receptor permeability to large molecules by extracellular Cl− and Na+ J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26922–26927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504966200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Korngreen A, Uzlaner N, Priel Z, Silberberg SD. Extracellular sodium regulates airway ciliary motility by inhibiting a P2X receptor. Nature. 1999;400:894–897. doi: 10.1038/23743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Korngreen A, Weil S, Cohen EB, Priel A, Kuzin L, Silberberg SD. Pore properties and pharmacological features of the P2X receptor channel in airway ciliated cells. J Physiol. 2006;571:503–517. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrell-Lagnado RD, Qureshi OS. Assembly and trafficking of P2X purinergic receptors (Review) Mol Membr Biol. 2008;25:321–331. doi: 10.1080/09687680802050385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto T, Brown D, Catalán M, Gonzalez-Begne M, Romanenko V, Melvin JE. Purinergic P2X7 receptors mediate ATP-induced saliva secretion by the mouse submandibular gland. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4815–4822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808597200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicke A, Kerschensteiner D, Soto F. Biochemical and functional evidence for heteromeric assembly of P2X1 and P2X4 subunits. J Neurochem. 2005;92:925–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RA. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:1013–1067. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. Pannexin-1 mediates large pore formation and interleukin-1β release by the ATP-gated P2X7 receptor. EMBO J. 2006;25:5071–5082. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perregaux D, Gabel CA. Interleukin-1β maturation and release in response to ATP and nigericin. Evidence that potassium depletion mediated by these agents is a necessary and common feature of their activity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15195–15203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raouf R, Chabot-Doré AJ, Ase AR, Blais D, Séguéla P. Differential regulation of microglial P2X4 and P2X7 ATP receptors following LPS-induced activation. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:496–504. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes JP, Hernández-Carballo CY, Pérez-Flores G, Pérez-Cornejo P, Arreola J. Lack of coupling between membrane stretching and pannexin-1 hemichannels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;380:50–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes JP, Pérez-Cornejo P, Hernández-Carballo CY, Srivastava A, Romanenko VG, Gonzalez-Begne M, Melvin JE, Arreola J. Na+ modulates anion permeation and block of P2X7 receptors from mouse parotid glands. J Membr Biol. 2008;223:73–85. doi: 10.1007/s00232-008-9115-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel T, Schmalzing G, Markwardt F. Influence of extracellular monovalent cations on pore and gating properties of P2X7 receptor-operated single-channel currents. Biophys J. 2007;93:846–858. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.103614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg SD, Chang TH, Swartz KJ. Secondary structure and gating rearrangements of transmembrane segments in rat P2X4 receptor channels. J Gen Physiol. 2005;125:347–359. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg SD, Li M, Swartz KJ. Ivermectin Interaction with transmembrane helices reveals widespread rearrangements during opening of P2X receptor channels. Neuron. 2007;54:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solle M, Labasi J, Perregaux DG, Stam E, Petrushova N, Koller BH, Griffiths RJ, Gabel CA. Altered cytokine production in mice lacking P2X7 receptors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:125–132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenneti L, Gibbons SJ, Talamo BR. Expression and trans-synaptic regulation of P2X4 and P2z receptors for extracellular ATP in parotid acinar cells. Effects of parasympathetic denervation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26799–26808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres GE, Egan TM, Voigt MM. Hetero-oligomeric assembly of P2X receptor subunits. Specificities exist with regard to possible partners. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6653–6659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres GE, Haines WR, Egan TM, Voigt MM. Co-expression of P2X1 and P2X5 receptor subunits reveals a novel ATP-gated ion channel. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:989–993. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Shigemoto-Mogami Y, Koizumi S, Mizokoshi A, Kohsaka S, Salter MW, Inoue K. P2X4 receptors induced in spinal microglia gate tactile allodynia after nerve injury. Nature. 2003;424:778–783. doi: 10.1038/nature01786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JT, Landon LA, Gibbons SJ, Talamo BR. Salivary gland P2 nucleotide receptors. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1999;10:210–224. doi: 10.1177/10454411990100020701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JT, Weisman GA, Landon LA, Park M, Camden JM. Salivary gland nucleotide receptors: evidence for functional expression of both P2X and P2Y subtypes. Eur J Morphol. 1998;36:170–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virginio C, MacKenzie A, North RA, Surprenant A. Kinetics of cell lysis, dye uptake and permeability changes in cells expressing the rat P2X7 receptor. J Physiol. 1999;519:335–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0335m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Z, Burnstock G. Expression of P2X receptors on rat microglial cells during early development. Glia. 2005;52:119–126. doi: 10.1002/glia.20227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young MT, Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. Amino acid residues in the P2X7 receptor that mediate differential sensitivity to ATP and BzATP. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:92–100. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]