Abstract

Brainstem–spinal cord connections play an essential role in adult pain processing, and the modulation of spinal pain network excitability by brainstem nuclei is known to contribute to hyperalgesia and chronic pain. Less well understood is the role of descending brainstem pathways in young animals when pain networks are more excitable and exposure to injury and stress can lead to permanent modulation of pain processing. Here we show that up to postnatal day 21 (P21) in the rat, the rostroventral medulla of the brainstem (RVM) exclusively facilitates spinal pain transmission but that after this age (P28 to adult), the influence of the RVM shifts to biphasic facilitation and inhibition. Graded electrical microstimulation of the RVM at different postnatal ages revealed a robust shift in the balance of descending control of both spinal nociceptive flexion reflex EMG activity and individual dorsal horn neuron firing properties, from excitation to inhibition, beginning after P21. The shift in polarity of descending control was also observed following excitotoxic lesions of the RVM in adult and P21 rats. In adults, RVM lesions decreased behavioural mechanical sensory reflex thresholds, whereas the same lesion in P21 rats increased thresholds. These data demonstrate, for the first time, the changing postnatal influence of the RVM in spinal nociception and highlight the central role of descending brainstem control in the maturation of pain processing.

Supraspinal modulation of the excitability of spinal nociceptive networks plays a key role in the perception and reaction to pain (Fields et al. 1977; Basbaum & Fields, 1979). The rostral ventral medulla (RVM) of the brainstem comprises several nuclei, which send descending projections to the spinal cord that modulate nociception (Fields et al. 1977; Basbaum & Fields, 1979). Physiological and behavioural responses of animals to nociceptive stimuli can be facilitated or inhibited by the activation of separate populations of cells within the RVM (Neubert et al. 2004; Carlson et al. 2007), which is the major target of efferent projections of the periaqueductal grey (PAG), a major site of action of opioid analgesics (Fields et al. 2006).

Little is known about the role of descending brainstem controls in young animals. Nociceptive circuits are considerably more excitable and less selective in young animals; dorsal horn neuron and cutaneous flexion reflex receptive fields are significantly larger, mechanical stimulation thresholds are lower and duration of nociceptive neuron firing is longer in the neonate than in the adult, which leads to enhanced behavioural sensitivity of young animals to painful stimulation (Fitzgerald, 2005; Baccei & Fitzgerald, 2005). The characteristic pain profile of young animals has led to suggestions that there is a lack of supraspinal control, particularly inhibition, over spinal pain circuits in early life, which matures with postnatal age. This is supported by the absence of spinal inhibition upon descending tract or PAG stimulation in the first postnatal weeks (Fitzgerald & Koltzenburg, 1986; van Praag & Frenk, 1991).

However, a lack of descending inhibition from selected sites or pathways does not necessarily mean that neonatal spinal nociceptive circuits are totally free of influence from supraspinal centres. Brainstem–spinal cord projections are some of the first to be formed in the fetal CNS (Cabana & Martin, 1984) and they clearly have some functional role, since neonatal spinalization leaves spinal reflexes permanently disorganized in adult rats (Fitzgerald & Koltzenburg, 1986; Levinsson et al. 1999) and reverses neonatal spinal GABAergic activity (Hathway et al. 2005).

The postnatal period may therefore represent a time when the normal balance, rather than the absolute onset, of descending brainstem controls are established. It is therefore important to investigate the development of descending excitation, or pro-nociception, as well as descending inhibition or antinociception. Recent reports of prolonged alterations in pain sensitivity over the whole body in both man and rodents following localized tissue injury at birth (Ren et al. 2004; Fitzgerald, 2005; Hermann et al. 2006; Schmelzle-Lubiecki et al. 2007) suggest that this balance of descending pain control may be set at a critical postnatal period and could be influenced by alterations in nociceptive afferent input.

We have tested the hypothesis that the balance of excitatory and inhibitory influence of specific brainstem nuclei upon developing spinal nociceptive circuits changes over postnatal life. We show that the output of the RVM undergoes a striking postnatal change, from exclusive facilitation of spinal nociceptive circuits from birth until the fourth postnatal week, when bi-phasic facilitation–inhibition of the same spinal pain circuits has developed.

Methods

Ethical approval

All animal procedures and experimenters were licensed by the UK Home Office and performed in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. As part of this process, ethical approval for the work was granted by the relevant authorities. Sprague–Dawley rats were housed with their littermates and mother (P3 and P21 groups) or in cages of six age-matched animals with free access to food and water. The room in which animals were housed had a 12 h–12 h light–dark cycle. Following experimentation, all animals were killed via an overdose of pentobarbitone (i.p.).

Electrical stimulation of RVM

Animals were anaesthetized with isoflurane (1.5%) and mounted on a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, California, USA), the skull exposed and bregma located. Stereotaxic co-ordinates for RVM were calculated [adult, lateral 0 mm, antero-posterior 9.7 mm, dorso-ventral −10 mm; postnatal day 21 (P21), lateral 0 mm, antero-posterior 9.2 mm, dorso-ventral −10.0 mm; and postnatal day 3 (P3) lateral 0 mm, antero-posterior 5.3 mm, dorso-ventral 6.5 mm].

A concentric bipolar stimulating electrode was lowered into the RVM using the co-ordinates above. Trains of stimuli of 500 μs pulse width were applied at 10 Hz, at amplitudes ranging from 5 to 200 μA (Neurolog, Digitimer, Welwyn Garden City, UK).

Recording of EMG

Electromyogram recordings were performed as described previously (Hathway & Fitzgerald, 2006). A bipolar concentric needle electrode (Ainsworks, Northampton, UK) was inserted in the lateral biceps femoris through a small skin incision. Such recording electrodes ensure that recorded activity is restricted to local muscle activity in small animals. Isoflurane anaesthesia was then reduced to 1.5%, (Univentor 400 anaesthesia unit, Zejtun, Malta) and the preparation allowed to equilibrate for 30 min prior to recording. Flexion EMG (full-wave rectified) activity was recorded following sequential (lowest to highest) von Frey hair (vFh) stimulation of the plantar surface of the foot. Since mechanical withdrawal thresholds are significantly lower in neonates than in adults (Fitzgerald, 2005), different hairs were used in each age group. In baseline conditions, responses to two subthreshold hairs, the threshold hair and a suprathreshold hair were chosen, and the same four hairs used in all subsequent stimulation conditions and for data analysis (see ‘Data analysis and statistics’ below). Each hair was applied three times, and the mean reading for each of the three presentations recorded. Raw EMG signals were conventionally amplified and displayed and fed to an analog-to-digital converter for further analysis using MacLab software (PowerLab 4S, AD Instruments, Oxford, UK).

Electrophysiology of single units

Dorsal horn cell electrophysiology was performed on P21 and adult (180 g) rats under isoflurane anaesthesia (1.5% as above). The animals were stabilized in a stereotaxic frame with ear and hip bars and a vertebral clamp. The ECG and temperature were continuously monitored and maintained at physiological levels. A laminectomy was performed in the lumbar spinal cord. A stimulating bipolar concentric needle electrode was positioned in the RVM at co-ordinates given above. Extracellular recordings from single dorsal horn cells were made in the L4/L5 lumbar dorsal horn in laminae III–V using standard techniques with 10 μm tip glass-coated tungsten microelectrodes.

Four adult rats were used and a total of 15 cells studied, whilst nine P21 rats were used and 30 cells recorded. Single spikes were isolated, and the mechanical vFh threshold, response to subthreshold, threshold and suprathreshold stimulation (two vFh above threshold) was measured before (baseline) and during electrical stimulation of the RVM (10 Hz, 5–200 μA, 500 μs pulse width). In both age groups, cells were determined to have changed if their activity increased or decreased by more than 10% of that cell's baseline values at 10 μA stimulus intensity. All recordings were fed into Chart software (AD Instruments, Chalgrove, UK), and data were analysed in Prism 3.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and Minitab (Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA). Animals were killed with an overdose of sodium pentobarbitone (i.p.) at the end of the experiment, and the accuracy of stimulating electrode placement assessed.

Immunohistochemistry

Spinal cord immunohistochemistry for c−fos protein expression was performed on 20 μm frozen sections following conventional 4% paraformaldehyde perfusion and postfixation in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h at 4°C followed by sucrose cryoprotection for at least 2 days. Spinal cord (L4–L5) was harvested from animals that had undergone electrical stimulation of the RVM (10 Hz, 500 μs, 10 μA in trains of 2 min on, 30 s off, for 15 min), 2 h before perfusion. Sections were processed for c-fos protein immunohistochemistry (1:60 000; Chemicon, Watford, Herts, UK) using standard methodology.

Lesions of RVM and behavioural testing

Mechanical withdrawal thresholds were determined as described previously (Hathway et al. 2005). Older animals (P21 and adult) were habituated to the testing room for an hour prior to testing, while P3 pups were habituated for 10 min and kept on a heated blanket. Mechanical hindlimb withdrawal thresholds were measured using vFh, applied sequentially (lowest to highest), with each hair being applied five times. Threshold was defined as lowest hair to evoke a withdrawal at 40% of presentations. Baseline values were established before RVM lesions. Animals were anaesthetized as described above, mounted in a stereotaxic frame and a microsyringe (Hamilton 88411, Hamilton, Reno, Nevada, USA) lowered into the RVM at the co-ordinates given above. Over the course of 5 min, 0.25 μl of kainate solution (2 mg ml−1; Sigma (Jakus et al. 2000) were injected into the RVM. The microsyringe was slowly withdrawn and the wound sutured using 5–0 Mersilk (Ethicon, Gargrave, UK). Following drug injection, animals were allowed to recover, and mechanical withdrawal thresholds were remeasured after 60 min Animals were killed by overdose of sodium pentobarbitone (IP).

Data analysis and statistics

Integrated EMG responses were measured over a range of vFh stimuli. The mean responses for three applications of each hair were calculated, and the stimulus response profile plotted. The area under the curve (AUC) of this vFh stimulus response was calculated and used as the overall nociceptive reflex response for each set of experimental conditions. Following RVM electrical stimulation, responses to the same four vFhs were remeasured every 10 min for 30 min postinjection. Data were collected in the same way, before and during RVM electrical stimulation experiments. These EMG data were normally distributed, and comparisons were made between the basal value of the AUC and those obtained following RVM manipulation. Statistical comparisons between the time points, stimulation intensities or age groups post-RVM manipulation were achieved using a repeated-measures one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test.

Single-unit electrophysiological data were analysed by classifying each cell as ‘excited’, ‘inhibited’ or ‘no change’ according to the effect of electrical stimulation in the RVM. Cells were assigned to the first two groups if their firing increased or decreased by more than 10% of that cell's baseline value. Population distributions of cells in each age group were compared using a χ2 test. Comparisons between cell groups and age groups were achieved using a repeated-measures two-way ANOVA with Bonferonni post hoc test.

Data from behavioural studies were not normally distributed and therefore non-parametric statistics were employed. Statistically significant differences among groups were analysed using Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn's post hoc test where appropriate.

All data were analysed using GraphPad Prism® (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Stimulation of RVM in young rats facilitates spinal nociceptive reflexes, while in adults the reflexes are inhibited

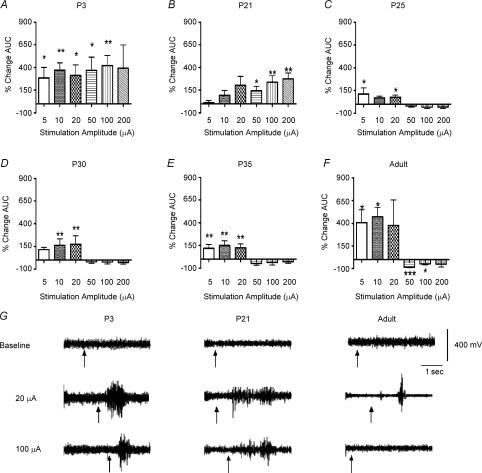

Figure 1 shows the effect of graded RVM stimulation, through a stereotaxically implanted bipolar electrode, upon mean integrated nociceptive reflex EMG activity. In adult rats (Fig. 1F), low-intensity (5–10 μA) RVM stimulation increased the EMG response to noxious mechanical hindpaw stimuli (P < 0.05; n= 5), but higher RVM stimulation intensities (50–100 μA) were strongly inhibitory, resulting in a significant reduction of the EMG response (P < 0.001 at 50 μA and P < 0.05 at 100 μA; n= 5).

Figure 1. Electrical stimulation of the RVM facilitates reflex response at P3 and P21, while adult reflexes are inhibited.

Histograms showing the percentage change in the integrated hindlimb EMG response to mechanical stimulation of the hindpaw during continuous electrical stimulation of the RVM at 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 or 200 μA, 500 μs, 10 Hz. Stimulation of RVM at P3 (A) and P21 (B) resulted in facilitation only, but the same stimulation in P25 (C), P30 (D), P35 (E) and adult rats (F) resulted in biphasic facilitation–inhibition. This time series reveals the development of descending inhibition through the fourth postnatal week. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, n= 6 at each age and intensity. Asterisks indicate significant change from baseline values (no RVM stimulation). G shows typical raw EMG responses illustrating the effect of 20 and 100 μA RVM electrical stimulation upon vFh-evoked reflex activity in P3, P21 and adult rats. Black arrows indicate vFh application.

The effect of RVM stimulation at the same range of intensities was markedly different in young rats. At P21, no inhibition occurred at any stimulus intensity tested; only facilitation was observed (P < 0.05 at 50 μA, P < 0.01 at 100 and 200 μA; n= 6; Fig. 1B). The same pattern was recorded in P3 rats, in which the EMG response was significantly increased at all RVM stimulation intensities (P < 0.05 at 5, 20 and 50 μA and P < 0.01 at 10 and 100 μA; n= 6; Fig. 1A).

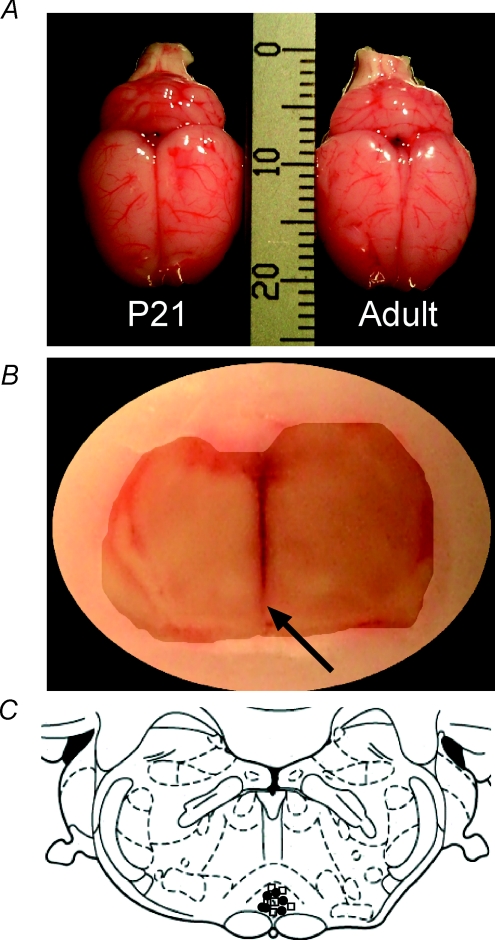

While the P3 rat is very small, making direct comparisons with the adult difficult, at P21 the rat brain is comparable in size to an adult brain (Fig. 2A), and stimulating electrode tracks could be reliably located postmortem (Fig. 2B). Figure 2C shows the stimulation sites at P21 (•) and adult (P40; □). Electrodes were located within the RVM, clustered in the nucleus raphe magnus, at both ages.

Figure 2. Comparison of adult and juvenile brains.

A, gross anatomical comparison of whole brains from juvenile (P21) and adult rats (P40). Brains from both age groups are of comparable size and do not differ significantly in either rostro-caudal or medio-lateral dimensions. B, coronal section through the brainstem of a P21 rat which had undergone RVM electrical stimulation. The black arrow indicates the termination of the needle tract, which is located in the nucleus raphe magnus (NRM). C, a map showing the locations of stimulating electrode placements in P21 (•) and adult rats (□) from the EMG study. All recording sites were within the NRM.

The change in response to RVM stimulation occurs after 3 weeks postnatal age

To establish the age of onset of RVM descending inhibition of nociceptive reflexes, we next performed a detailed time course study of RVM stimulation upon spinal nociceptive activity. The same RVM stimulation protocol was tested at three time points between P21 and adult (P40; Fig. 1). At P25, low-intensity stimulation continued to facilitate the nociceptive EMG response but high-intensity stimulation caused weak inhibition (Fig. 1C). At P30 and P35, progressively greater degrees of inhibition were evoked by RVM stimulation (Fig. 1D and E, respectively) approaching that seen in the adult (Fig. 1F).

The change in RVM descending control is also observed at the level of single dorsal horn cells

To test whether the change in RVM descending control over nociceptive reflexes was acting upon the sensory component of spinal nociceptive circuits, the effect of RVM stimulation was tested upon single dorsal horn neuronal activity in laminae III–V. Spike activity evoked by noxious mechanical skin stimulation was recorded in 30 cells from P21 rats (n= 15) and 15 cells from adult rats (n= 8) at baseline and during RVM stimulation.

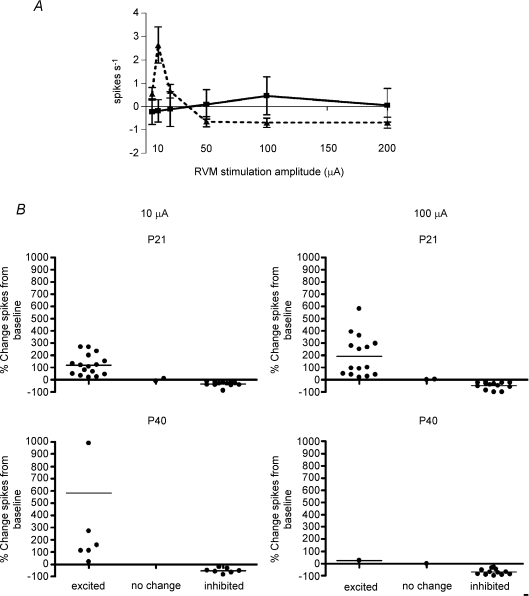

Figure 3A shows the mean effect of graded RVM stimulation (5–200 μA) upon the evoked activity of P21 and adult (P40) dorsal horn cells. While the net effect on adult cells was facilitation at low RVM stimulation intensities, this reversed to inhibition above 50 μA. In contrast, the net effect upon P21 cells was that they were unable to become inhibited at any RVM stimulation intensity. The same pattern of RVM influence is observed as that seen in the reflex studies, namely excitation at P21 and biphasic facilitation–inhibition at P40.

Figure 3. The direction of stimulus-evoked changes in dorsal horn neuron firing depends upon stimulus intensity and the age of animal.

A, stimulus–response profiles of adult and P21 cells over the entire range of RVM stimulation amplitudes. While the adult cells (▵) displayed a biphasic response, P21 cells (□) responded in a monophasic manner. B, scatter plots illustrating the percentage change in spiking of individual dorsal horn neurons from P21 and adult rats during 10 and 100 μA RVM stimulation. χ2 analysis of the populations in P21 and adult groups showed highly significant differences in the distribution of cells at these ages (P < 0.0001) at both 10 and 100 μA stimulation intensities.

However, since individual neurons at both ages differed strikingly in their response to RVM stimulation and the great majority (90%) were either excited or inhibited, pooling the data from these cells belied the true pattern of change. This is evident from Fig. 3B, which shows scatter plots of the change in individual dorsal horn neuron evoked responses during low-intensity (10 μA) and high-intensity (100 μA) RVM stimulation in P21 and adult rats. A very clear pattern of the balance of inhibition and excitation emerges from this type of analysis. While a subpopulation of cells that are inhibited by both low- and high-intensity RVM stimulation can be observed at both ages (ANOVA effect of age and stimulus intensity not significant), the incidence of facilitated cells is dependent upon age. At low stimulus intensities, 50% of cells in the adult were facilitated, but at higher stimulus intensities, only one cell out of 15 was facilitated, in contrast to the high incidence of facilitated cells at P21 (Fig. 3B). This difference in the pattern of excitation and inhibition at the two ages was highly significant (χ2 analysis, P < 0.0001).

Another marked difference between the two ages was that at P21, cells which were facilitated by RVM stimulation at 10 μA remained facilitated at all stimulus intensities and were never inhibited in this experiment. This was in contrast to the adult population of cells that were facilitated at 10 μA, the majority of which (6 of 7) became inhibited at stimulation intensities over 50 μA.

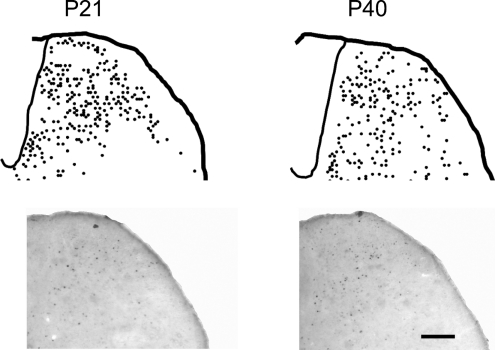

To confirm that RVM spinal cord connections are comparable at the two ages, the distribution of c−fos protein-positive neurons in the spinal dorsal horn following RVM stimulation (10 μA for 15 min) in P21 (n= 4) and adult rats (n= 4) was compared. Figure 4 shows that there was no significant difference in the density and distribution of c−fos protein-positive cells in the dorsal horn in both age groups.

Figure 4. Electrical stimulation of the RVM activates similar populations of dorsal horn neurons in both young and adult rats.

Mapping the distribution of c-fos protein-positive neurons in the spinal dorsal horn of P21 and adult rats shows that similar populations of cells are activated in both age groups. The differences observed with EMG and single-unit electrophysiological recordings cannot be due to unintentional sampling bias or differences in the innervation of the dorsal horn by descending fibres. Upper mages are the summated expression patterns from 3 animals at each age, and lower images are examples. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

The postnatal change in RVM descending control is supported by lesion studies

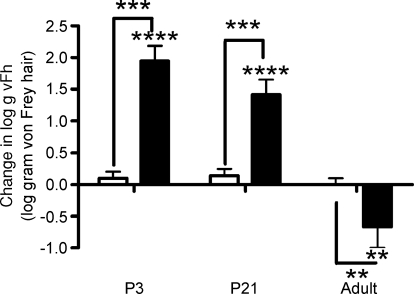

The change from descending excitation to inhibition of nociceptive reflexes by RVM stimulation after P21 led us to hypothesize that RVM lesions may have very different effects in young and adult rats. In adults, RVM ablation resulted in decreased hindpaw mechanical thresholds (Fig. 5), as would be expected if inhibitory control is removed. In marked contrast, RVM kainate ablation in P3 and P21 rats resulted in an increase in mechanical withdrawal thresholds (P < 0.001, n= 12 per group; Fig. 5), suggesting that excitatory control was removed. Saline microinjections (as control) into the RVM had no effect upon mechanical thresholds in any of the age groups tested.

Figure 5. Ablation of RVM increases mechanical thresholds in neonatal rats and decreases them in adult rats.

Excitotoxic lesioning of the RVM increases hindpaw mechanical thresholds in P3 and P21 rats but significantly decreases them in adult animals. Bars indicate mean values ±s.e.m. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001, n= 6–12 in each group. Asterisks immediately above bars indicate significant change from baseline whilst those between bars indicate differences between open bars saline- and filled bars kainate-treated animals within an age group.

Discussion

These results identify an important and previously undescribed stage in the development of pain pathways that has important implications for understanding of both infant and adult pain. The study shows that the RVM has a powerful tonic influence over spinal nociception from birth and that this influence changes sharply, during the fourth postnatal week, from facilitation to inhibition.

Descending facilitation by RVM of spinal nociceptive circuits in young rats

The adult RVM is known to play a key role in pain control. Together with the PAG and dorsal horn of the spinal cord, it forms a well-described endogenous control system that modulates both tonic nociceptive processing and the persistent allodynia and hyperalgesia associated with inflammation and nerve injury (Fields et al. 2006). While the involvement of the RVM in descending modulation of nociceptive processing was originally demonstrated using the tail-flick reflex to noxious heating (Fields et al. 1983; Fields & Heinricher, 1985), RVM descending control of hindlimb withdrawal reflexes and of dorsal horn cell activity is also well described, and these output measures of nociceptive processing were used here because they are better suited to developmental studies (Gilbert & Stelzner, 1979; Fitzgerald, 1987; Carlson et al. 2007; Goncalves et al. 2007). Our data show that the RVM can significantly modulate pain networks at all ages but that a striking shift from a predominantly facilitatory drive in the early postnatal period to tonic inhibition in the adult takes place after 3 weeks of age. Descending facilitation from the RVM has been extensively reported in adult animals but mostly in animals that have been subjected to inflammatory or neuropathic injury and are models of pathological pain states (Burgess et al. 2002). In normal adults, the net output of electrical stimulation and opioid injection into the RVM is inhibitory (Fields et al. 1977; Gilbert & Franklin, 2002). It should be noted that in addition to its role in nociception, it has been suggested that the RVM plays a wider role in somatosensation, for example touch (Mason, 2001). How the postnatal changes we have observed in the role of the RVM in nociception impact upon innocuous sensory processing cannot be determined from our study; however, it is reasonable to assume that any changes would be similar to those described here.

The facilitation of spinal pain networks in young animals was observed with two methods of RVM manipulation: electrical stimulation over a wide range of stimulus intensities that are sufficient to activate the majority of neurons within the RVM (Hentall et al. 1991) and kainate ablation, which selectively destroys neuronal cell bodies, leaving fibres of passage intact (Coyle et al. 1978; Sanoja et al. 2008). Both of these methods were comparable across the age range examined, reducing the possibility that the facilitation in young rats was the result of inaccurate electrode or microinjection placement or acted upon different brainstem nuclei in young and adult animals. The use of bipolar stimulating electrodes restricts stimulation to neuropil immediately around the electrode tip, which was particularly important in the younger age groups. Furthermore, both our postmortem evaluations of the electrode placement and our comparisons of the overall size of brains in P21 and adult age groups illustrate that the same volume of tissue would have been stimulated in all the groups studied and that the accuracy of the electrode placement was comparable across groups. Finding the change from descending facilitation to inhibition at both the reflex and single dorsal horn cell level adds additional strength to these data.

Mechanisms underlying the postnatal change in RVM descending control

Our results point to alterations in RVM neuronal activity as the cause of the change in descending control. Electrical stimulation of RVM networks had very different effects at different ages. As previously reported, facilitation of nociception in adults occurred at lower stimulus intensities with higher stimulus intensities required to recruit descending inhibition. However, increasing stimulus strength before P21 did not produce inhibition in our EMG studies, suggesting that brainstem inhibitory circuitry is immature prior to P21. Importantly, single-unit recordings clearly demonstrate that cells in the dorsal horn can be inhibited by electrical stimulation of the RVM before P21, suggesting that the essential components of inhibitory circuitry are present. It is the net output of the RVM upon the dorsal horn cell population, hence upon nociceptive reflexes, which is subject to considerable postnatal maturation.

How identical stimulation parameters in the different age groups result in significantly different effects at the level of the dorsal horn is yet to be determined. Electrophysiological studies have classified adult RVM cells according to their responses to peripheral noxious heat. Cells that increase their firing in response to noxious heating are termed ‘on’ cells, those that display a pause in firing are termed ‘off’ cells and a third population that do not change their firing properties are termed ‘neutral’ cells (Fields & Heinricher, 1985). The switch in RVM control may result from a change in the proportion of these different cell types through postnatal development, or a maturation of reciprocal interneuronal connections between them and their inputs from the spinal cord or from the PAG and other CNS areas. It is notable that descending inhibition from the PAG can only be observed from P21 onwards (van Praag & Frenk, 1991), suggesting that PAG–RVM connections may be absent before then. Further studies are required that investigate the physiological properties of RVM cell types through the postnatal period to provide a better understanding of these phenomena.

There are many recent data illustrating the importance of the RVM in mediating the descending control of nociception in diseased and healthy animals (Fields et al. 1977; Carlson et al. 2007; Bee & Dickenson, 2008; Sanoja et al. 2008), and many reports have shown that RVM-mediated facilitation of nociception plays a significant role in the pain associated with both neuropathic and inflammatory injury (Terayama et al. 2000; Hurley & Hammond, 2001; Sykes et al. 2007). Our data show that it is these facilitatory pathways that are important in young animals. Descending facilitation is present from birth and has a powerful excitatory influence over spinal nociception; only after three postnatal weeks do the inhibitory pathways begin to exert any influence. This descending excitation in early life could contribute to the activity-dependent development of nociceptive pathways (Fitzgerald, 2005) and to the plastic changes in central pain processing that follow neonatal pain experience (Hermann et al. 2006).

Acknowledgments

Work funded by grants from the Wellcome Trust and The Medical Research Council (UK).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- EMG

electromyography

- P

postnatal day

- PAG

periaqueductal grey

- RVM

rostroventral medulla

Author contributions

G.J.H. conceived, designed, analysed and interpreted data regarding EMG, single-unit and lesion experiments, drafted, revised and approved the manuscript. S.K. conceived, designed and interpreted the single-unit experiments as well as drafting, revising and approving the manuscript. L.L. designed the lesion experiments, revised and approved the article. M.F. conceived, designed, analysed and interpreted data regarding EMG, single-unit and lesion experiments, drafted, revised and approved the manuscript.

References

- Baccei ML, Fitzgerald MF. The development of pain pathways and mechanisms. In: McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M, editors. The Textbook of Pain. London: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 143–158. [Google Scholar]

- Basbaum AI, Fields HL. The origin of descending pathways in the dorsolateral funiculus of the spinal cord of the cat and rat: further studies on the anatomy of pain modulation. J Comp Neurol. 1979;187:513–531. doi: 10.1002/cne.901870304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bee LA, Dickenson AH. Descending facilitation from the brainstem determines behavioural and neuronal hypersensitivity following nerve injury and efficacy of pregabalin. Pain. 2008;140:209–223. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess SE, Gardell LR, Ossipov MH, Malan TP, Jr, Vanderah TW, Lai J, Porreca F. Time-dependent descending facilitation from the rostral ventromedial medulla maintains, but does not initiate, neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5129–5136. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-05129.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabana T, Martin GF. Developmental sequence in the origin of descending spinal pathways. Studies using retrograde transport techniques in the North American opossum (Didelphis virginiana) Brain Res. 1984;317:247–263. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(84)90102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson JD, Maire JJ, Martenson ME, Heinricher MM. Sensitization of pain-modulating neurons in the rostral ventromedial medulla after peripheral nerve injury. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13222–13231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3715-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Molliver ME, Kuhar MJ. In situ injection of kainic acid: a new method for selectively lesioning neural cell bodies while sparing axons of passage. J Comp Neurol. 1978;180:301–323. doi: 10.1002/cne.901800208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields HL, Basbaum AI, Clanton CH, Anderson SD. Nucleus raphe magnus inhibition of spinal cord dorsal horn neurons. Brain Res. 1977;126:441–453. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90596-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields HL, Basbaum AI, Heinricher MM. Central nervous system mechanisms of pain modulation. In: McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M, editors. The Textbook of Pain. London: Elsevier Churchill Linvingstone; 2006. pp. 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Fields HL, Bry J, Hentall I, Zorman G. The activity of neurons in the rostral medulla of the rat during withdrawal from noxious heat. J Neurosci. 1983;3:2545–2552. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-12-02545.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields HL, Heinricher MM. Anatomy and physiology of a nociceptive modulatory system. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1985;308:361–374. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1985.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald M. Spontaneous and evoked activity of fetal primary afferents in vivo. Nature. 1987;326:603–605. doi: 10.1038/326603a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald M. The development of nociceptive circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:507–520. doi: 10.1038/nrn1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald M, Koltzenburg M. The functional development of descending inhibitory pathways in the dorsolateral funiculus of the newborn rat spinal cord. Brain Res. 1986;389:261–270. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(86)90194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert AK, Franklin KB. The role of descending fibers from the rostral ventromedial medulla in opioid analgesia in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;449:75–84. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01974-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert M, Stelzner DJ. The development of descending and dorsal root connections in the lumbosacral spinal cord of the postnatal rat. J Comp Neurol. 1979;184:821–838. doi: 10.1002/cne.901840413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves L, Almeida A, Pertovaara A. Pronociceptive changes in response properties of rostroventromedial medullary neurons in a rat model of peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:2188–2195. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathway GJ, Fitzgerald M. Time course and dose-dependence of nerve growth factor-induced secondary hyperalgesia in the mouse. J Pain. 2006;7:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathway GJ, Harrop JE, Baccei ML, Walker S, Moss A, Fitzgerald M. A postantal switch in GABAergic control of spinal reflexes. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;23:112–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentall ID, Barbaro NM, Fields HL. Spatial and temporal variation of microstimulation thresholds for inhibiting the tail-flick reflex from the rat's rostral medial medulla. Brain Res. 1991;548:156–162. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91117-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann C, Hohmeister J, Demirakca S, Zohsel K, Flor H. Long-term alteration of pain sensitivity in school-aged children with early pain experiences. Pain. 2006;125:278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley RW, Hammond DL. Contribution of endogenous enkephalins to the enhanced analgesic effects of supraspinal μ opioid receptor agonists after inflammatory injury. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2536–2545. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02536.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakus J, Stránsky A, Poliacek I, Baráni H, Bosel’ová L. Kainic acid lesions to the lateral tegmental field of medulla: effects on cough, expiration and aspiration reflexes in anesthetized cats. Physiol Res. 2000;49:387–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinsson A, Luo XL, Holmberg H, Schouenborg J. Developmental tuning in a spinal nociceptive system: effects of neonatal spinalization. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10397–10403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10397.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason P. Contributions of the medullary raphe and ventromedial reticular region to pain modulation and other homeostatic functions. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:737–777. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubert MJ, Kincaid W, Heinricher MM. Nociceptive facilitating neurons in the rostral ventromedial medulla. Pain. 2004;110:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Frenk H. The development of stimulation-produced analgesia (SPA) in the rat. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1991;64:71–76. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90210-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren K, Anseloni V, Zou SP, Wade EB, Novikova SI, Ennis M, Traub RJ, Gold MS, Dubner R, Lidow MS. Characterization of basal and re-inflammation-associated long-term alteration in pain responsivity following short-lasting neonatal local inflammatory insult. Pain. 2004;110:588–596. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanoja R, Vanegas H, Tortorici V. Critical role of the rostral ventromedial medulla in early spinal events leading to chronic constriction injury neuropathy in rats. J Pain. 2008;9:532–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.01.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzle-Lubiecki BM, Campbell KA, Howard RH, Franck L, Fitzgerald M. Long-term consequences of early infant injury and trauma upon somatosensory processing. Eur J Pain. 2007;11:799–809. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes KT, White SR, Hurley RW, Mizoguchi H, Tseng LF, Hammond DL. Mechanisms responsible for the enhanced antinociceptive effects of μ-opioid receptor agonists in the rostral ventromedial medulla of male rats with persistent inflammatory pain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:813–821. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.121954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terayama R, Guan Y, Dubner R, Ren K. Activity-induced plasticity in brain stem pain modulatory circuitry after inflammation. Neuroreport. 2000;11:1915–1919. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200006260-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo M, Gebhart GF. Biphasic modulation of spinal nociceptive transmission from the medullary raphe nuclei in the rat. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:746–758. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.2.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo M, Gebhart GF. Facilitation and attenuation of a visceral nociceptive reflex from the rostroventral medulla in the rat. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1007–1019. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]