Abstract

Presynaptic terminal depolarization modulates the efficacy of transmitter release. Residual Ca2+ remaining after presynaptic depolarization is thought to play a critical role in facilitation of transmitter release, but its downstream mechanism remains unclear. By making simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic recordings at the rodent calyx of Held synapse, we have investigated mechanisms involved in the facilitation and depression of postsynaptic currents induced by presynaptic depolarization. In voltage-clamp experiments, cancellation of the Ca2+-dependent presynaptic Ca2+ current (IpCa) facilitation revealed that this mechanism can account for 50% of postsynaptic current facilitation, irrespective of intraterminal EGTA concentrations. Intraterminal EGTA, loaded at 10 mm, failed to block postsynaptic current facilitation, but additional BAPTA at 1 mm abolished it. Potassium-induced sustained depolarization of non-dialysed presynaptic terminals caused a facilitation of postsynaptic currents, superimposed on a depression, with the latter resulting from reductions in presynaptic action potential amplitude and number of releasable vesicles. We conclude that presynaptic depolarization bidirectionally modulates transmitter release, and that the residual Ca2+ mechanism for synaptic facilitation operates in the immediate vicinity of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in the nerve terminal.

Short-term synaptic plasticity is thought to be a cellular mechanism underlying working memory (Mongillo et al. 2008). Presynaptic membrane potential plays a critical role in bidirectional short-term plasticity, with presynaptic depolarization causing facilitation as well as depression of transmitter release. It is widely accepted that presynaptic Ca2+, remaining from previous entry, facilitates transmitter release evoked by a subsequent nerve impulse (Katz & Miledi, 1968; for a review see Zucker & Regehr, 2002). However, the downstream mechanism of this residual Ca2+ remains controversial. Proposed mechanisms include (i) linear summation of intraterminal Ca2+ concentrations (Katz & Miledi, 1968; Felmy et al. 2003), (ii) Ca2+ binding to putative high-affinity sites, which sensitize Ca2+ sensors for vesicle fusion (Yamada & Zucker, 1992; Bertram et al. 1996; Atluri & Regehr, 1996; Tang et al. 2000), (iii) saturation of endogenous Ca2+ buffers (Blatow et al. 2003; Felmy et al. 2003; Matveev et al. 2004), and (iv) Ca2+-dependent facilitation of presynaptic Ca2+ currents (IpCa, Borst & Sakmann, 1998b; Cuttle et al. 1998; Forsythe et al. 1998; Inchauspe et al. 2004; Ishikawa et al. 2005).

The mechanisms underlying facilitation of transmitter release have been studied most extensively on paired-pulse facilitation (PPF), particularly in relation to global residual Ca2+ concentration in the nerve terminal (Atluri & Regehr, 1996; Müller et al. 2007). Besides PPF caused by action potentials (APs), nerve terminals can moderately be depolarized for a sustained period by a variety of mechanisms, including (i) extracellular K+ accumulation resulting from neuronal activity (Singer & Lux, 1973; Malenka et al. 1981), (ii) activation of presynaptic ligand-gated channels (Turecek & Trussell, 2001), and (iii) propagation of dendro-somatic depolarization (Alle & Geiger, 2006; Scott et al. 2008; Christie & Jahr, 2008). Recently, Awatramani et al. (2005) demonstrated that a sustained small presynaptic depolarization, below the threshold of Ca2+ current induction, enhances transmitter release via tonic Ca2+ entry, and named it as the small depolarization-dependent enhancement (SDE).

At rodent calyces of Held, unlike at squid synapses (Charlton et al. 1982), IpCa undergoes facilitation upon repetitive activation (Borst & Sakmann, 1998b; Cuttle et al. 1998). This IpCa facilitation is Ca2+ dependent, being mediated by neuronal Ca2+ sensor 1 (NCS-1, Tsujimoto et al. 2002) and calmodulin (CaM, DeMaria et al. 2001; Nakamura et al. 2008), and occurs exclusively in P/Q-type Ca2+ channels (Inchauspe et al. 2004; Ishikawa et al. 2005). In P/Q-type Ca2+ channel knockout mice, PPF evoked in low [Ca2+] solution is significantly reduced at the calyx of Held, suggesting that IpCa facilitation is an essential mechanism underlying PPF (Inchauspe et al. 2004; Ishikawa et al. 2005). However, it has been reported that presynaptic depolarization is not at all (Awatramani et al. 2005), or only rarely (Felmy et al. 2003), accompanied by facilitation of IpCa. Although it has recently been reported that IpCa facilitation contributes to 40% of PPF at the calyx of Held (Müller et al. 2008), it remains unknown whether it contributes to different types of synaptic facilitation, and under various presynaptic Ca2+ buffering strengths.

In the present study, by making simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic recording at the calyx of Held, we have addressed mechanisms underlying the modulation of transmitter release by a sustained or a paired-pulse presynaptic depolarization, and their relative contributions to facilitation of transmitter release in various intraterminal Ca2+ buffer conditions. Furthermore, to assess the main locus of facilitation mechanisms, we tested the effects of EGTA and BAPTA on presynaptic facilitations by loading them into the nerve terminal. Our results suggest that presynaptic facilitation mechanisms, including the IpCa facilitation mechanism, operate in the immediate vicinity of Ca2+ channels.

Methods

Slice preparations and solutions

All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Physiological Society of Japan. C57BL mice at postnatal days (P) 10–12 (119 mice in total), or P14–16 Wistar rats (30 rats in total, data not shown) were killed by decapitation under inhalation anaesthesia with halothane (1–2%). Transverse slices (150–175 μm in thickness) containing the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body were cut from a tissue block of the brainstem. The medial nucleus of trapezoid body (MNTB) neurons and calyces were viewed with a ×60 (Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) water immersion lens attached to an upright microscope (Axioskop; Zeiss). Each slice was superfused with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing (in mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 3 myo-inositol, 2 sodium pyruvate, and 0.5 ascorbic acid (pH 7.4, with 5% CO2 and 95% O2, 295–305 mosmol l−1). For recording EPSCs, the aCSF contained bicuculline methiodide (10 μm) and strychnine hydrochloride (0.5 μm) to block spontaneous inhibitory synaptic currents. The aCSF also contained kynurenic acid (1 mm) to minimize AMPA receptor saturation unless otherwise noted. For recording IpCa, NaCl in the aCSF was replaced by equimolar tetraethylammonium (TEA) chloride (10 mm), and tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μm) was added to the aCSF. The presynaptic patch pipette solution contained (mm): 110 CsCl, 10 TEA-Cl, 0.5 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 40 Hepes, 2 ATP (Mg salt), 12 phosphocreatine and 0.5 GTP (Na salt, pH 7.3, adjusted with CsOH, 290–300 mosmol l−1). The liquid junction potential in this solution was 3 mV, which was corrected for. For recording presynaptic action potentials, the presynaptic patch pipette solution contained (mm): 97.5 potassium gluconate, 32.5 KCl, 10 Hepes, 0.5 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 10 potassium glutamate, 2 ATP (Mg salt), 12 phosphocreatine and 0.5 GTP (Na salt) (pH 7.3, adjusted with KOH, 290–300 mosmol l−1). The liquid junction potential in this solution was 7 mV, which was corrected for. For postsynaptic recordings, the patch pipette solution contained (mm): 110 CsCl, 10 Hepes, 5 EGTA and MgCl2. When the aCSF did not contain TTX, N-(2,6-diethylphenylcarbamoylmethyl)-triethylammonium chloride (QX314-Cl, 5 mm) was included in the postsynaptic pipette solution to suppress AP generation. Presynaptic pipette perfusion was performed as previously described (Hori et al. 1999), but using a glass tube (o.d. 0.3 mm) instead of a plastic tube, pulled so that its tip reached 0.15 mm from the tip of the patch pipette. In this method, infusion of small molecules such as methane sulfonate into the calyces is complete within 2 min.

Recording and data analysis

All recordings were made at room temperature (23–27°C). Paired pre- and postsynaptic whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from a calyx nerve terminal and a MNTB principal cell. EPSCs were evoked by afferent fibre stimulation, presynaptic APs elicited by 1 ms depolarizing pulses, or by IpCa elicited by an AP waveform command pulse under voltage clamp. The AP waveform was taken from an AP elicited by presynaptic fibre stimulation in a P14 mouse calyx. Presynaptic fibre stimulation was made by a bipolar platinum electrode, which was positioned near the midline of slices. Miniature EPSCs were recorded in the presence of TTX, but in the absence of cyclothiazide (CTZ) and kynurenate. In voltage-clamp experiments, the holding potential for presynaptic terminals and postsynaptic cells was −70 mV. The resistance of the patch pipette was 4–7 MΩ for presynaptic recordings and 2–4 MΩ for postsynaptic recordings. The series resistance of presynaptic recording was typically 7–15 MΩ and was compensated by 70–90% in the voltage-clamp experiments. Membrane currents or potentials were recorded using a patch-clamp amplifier having high input impedance in current-clamp mode (1011Ω, Axopatch 700A; Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). Records were digitized at 50–100 Hz by a Digidata 1322A interface (Axon Instruments). Presynaptic voltage-gated currents were leak-subtracted by using a scaled pulse divided by 8 (P/N) protocol. All data were expressed as mean ±s.e.m. (error bars in figures). Student's t test, with or without ANOVA, was used for statistical analysis. Differences were considered significant if P values < 0.05.

The deconvolution analysis of postsynaptic current records was performed using the analysis routine written in Igo Pro (Sakaba & Neher, 2001) to estimate release rate of synaptic vesicles. The readily releasable pool (RRP) size was estimated by integrating the release rate between the beginning of a stimulus protocol and the end of the depleting stimulus (Sakaba & Neher, 2001). The effect of pool recovery on the RRP size (9.3% in Sakaba & Neher, 2001) was not corrected for. Evoked EPSCs were recorded in the presence of CTZ (100 μm) and kynurenate (1 mm). As kynurenate (1 mm) reduced the EPSC amplitude to 48 ± 5% (n= 4), the factor of attenuation was taken as 0.5.

Results

A sustained presynaptic depolarization facilitates presynaptic Ca2+ currents and transmitter release

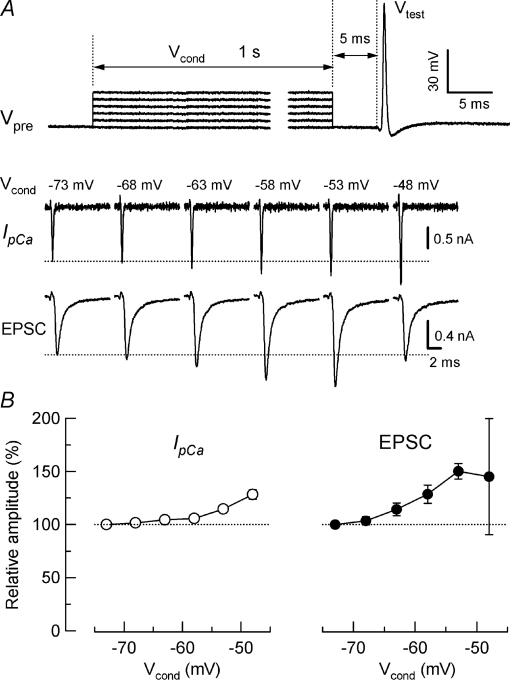

It has been reported that SDE is unaccompanied by a facilitation of IpCa (Awatramani et al. 2005). To reinvestigate this issue at the calyx of Held, we performed simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic voltage-clamp recordings, and evoked EPSCs by IpCa induced by AP waveform test pulses (Vtest, Fig. 1A), instead of square pulses (Awatramani et al. 2005). Prior to Vtest, we depolarized presynaptic terminals using square conditioning pulses (Vcond), which were shorter (1 s vs. 5 s), but stepping to more positive membrane potentials (−48 mV vs.−60 mV), compared with those used by Awatramani et al. (2005). As illustrated in Fig. 1, IpCa and EPSCs showed clear facilitations following presynaptic depolarization. When the presynaptic terminal was depolarized by 20 mV (Vcond, −53 mV), EPSCs showed a maximal facilitation (to 150 ± 7%, n= 7 synapses), together with IpCa facilitation (to 115 ± 3%, Fig. 1B). This magnitude of EPSC facilitation was smaller than that reported by Awatramani et al. (2005), in which presynaptic pipettes contained 25 μm BAPTA instead of 0.5 mm EGTA (see also Table 1). Upon stronger presynaptic depolarization, the magnitude of EPSC facilitation tended to decline. Essentially the same results were obtained from rat calyces of Held (data not shown).

Figure 1. Facilitation of Ca2+-dependent presynaptic Ca2+ current (IpCa) and EPSCs by sustained presynaptic depolarization.

Simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic voltage-clamp recordings of IpCa and EPSCs in the presence of TTX at the calyx of Held of mice. A, top traces show presynaptic command voltage protocol (Vpre), comprising 1 s depolarizing conditioning pulse (Vcond) followed by an action potential (AP) waveform test pulse (Vtest). Sample records of IpCa (middle traces) and EPSCs (bottom traces) elicited by Vtest, after depolarizing calyces from holding potential (−73 mV) to various membrane potentials (Vcond indicated above the traces). Dotted lines indicate control amplitudes of IpCa and EPSCs elicited by Vtest without Vcond. B, summary data from 7 synapses. Relative changes of IpCa (left panel, open circles) and EPSCs (right panel, filled circles) produced by Vcond (abscissae). Ordinate (relative amplitude) indicates the relative amplitudes of IpCa and EPSCs compared with those without Vcond. Essentially the same results were obtained from calyces of Held of rats (data not shown).

Table 1.

Percentage contributions of IpCa facilitations to EPSC facilitations in different intraterminal Ca2+ buffer conditions

| Buffers | EPSC | IpCa | IpCa | EPSC | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| facilitation (%) | facilitation (%) | contribution (%) | amplitude (nA) | |||

| SDE (−53mV Vcond, 1 mm kynurenate) | 0.5 mm EGTA | 154 ± 17 | 111 ± 2.2 | 45 ± 6 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 5 |

| 10 mm EGTA | 123 ± 1.3 | 105 ± 1.2 | 34 ± 6 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 4 | |

| 0.025 mm BAPTA | 213 ± 28 | 120 ± 1.7 | 67 ± 4 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 4 | |

| PPF (5 ms ISI, BoNT/E) | 0.1 mm EGTA | 224 ± 19 | 127 ± 5.8 | 40 ± 8 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 5 |

| 0.5 mm EGTA | 185 ± 7.2 | 119 ± 1.5 | 54 ± 9 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 5 | |

| 10 mm EGTA | 176 ± 7.5 | 116 ± 2.8 | 48 ± 10 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 4 |

SDE, small depolarization-dependent enhancement; Vcond, conditioning pulse; PPF, paired pulse facilitation; ISI, inter-stimulus interval; BoNT/E, botulinum toxin E; IpCa, presynaptic Ca2+ current.

We could reproduce the lack of IpCa facilitation in both mice (Supplemental Fig. 1, available online only) and rats (data not shown), using a square pulse Vtest instead of AP waveform, and 5 s instead of 1 s Vcond, according to the protocol of Awatramani et al. (2005). These results are consistent with previous reports that IpCa evoked by a square test pulse, stepping up beyond +20 mV, does not undergo facilitation upon repetitive activation (Cuttle et al. 1998; Tsujimoto et al. 2002), whereas IpCa evoked by AP waveform pulses shows facilitation (Fig. 1, see also Borst & Sakmann, 1998b; Tsujimoto et al. 2002). A large square pulse may presumably saturate the gating acceleration mechanism of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) underlying IpCa facilitation (Borst & Sakmann, 1998b; Cuttle et al. 1998). At the calyx of Held, the open probability of Ca2+ channels activated by an AP waveform command pulse is submaximal (50% and 35%, respectively in P8–12 and P16–18 mice, Yang & Wang, 2006; 69% in P8–10 rats, Borst & Sakmann, 1998a), therefore allowing facilitation of Ca2+ currents.

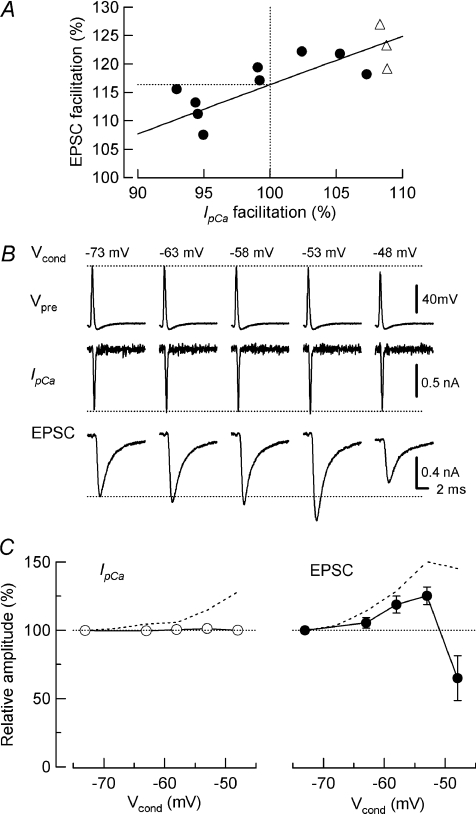

IpCa facilitation-dependent and -independent components of SDE

To estimate the contributions of IpCa facilitation, and other mechanisms, to the facilitation of transmitter release, we adjusted the amplitude of AP waveform Vtest until the IpCa amplitude became identical to that without Vcond (100%, Fig. 2A). This IpCa cancellation attenuated EPSC facilitation (Fig. 2B), thereby dissecting the EPSC facilitation into IpCa facilitation-dependent and -independent components (Fig. 2C). The IpCa facilitation-dependent component of EPSC facilitation was 45 ± 6% on average at −53 mV Vcond with 0.5 mm EGTA in presynaptic pipettes (Table 1).

Figure 2. Experimental dissection of small depolarization-dependent enhancement (SDE) into IpCa facilitation-dependent and -independent components.

A, protocol used for cancellation of IpCa facilitation. AP waveform command pulse was gradually diminished and a null point of IpCa facilitation was determined by the least squares method from a linear regression line for data points (filled circles) including those in control (open triangles). B, sample records of AP command pulses (Vpre), IpCa and EPSCs after cancelling IpCa facilitation. C, EPSC facilitation and depression (right panel) after cancelling IpCa facilitation (left panel). Summary data from 8 synapses. Dashed lines are data in Fig. 1B (without IpCa cancellation) for comparison.

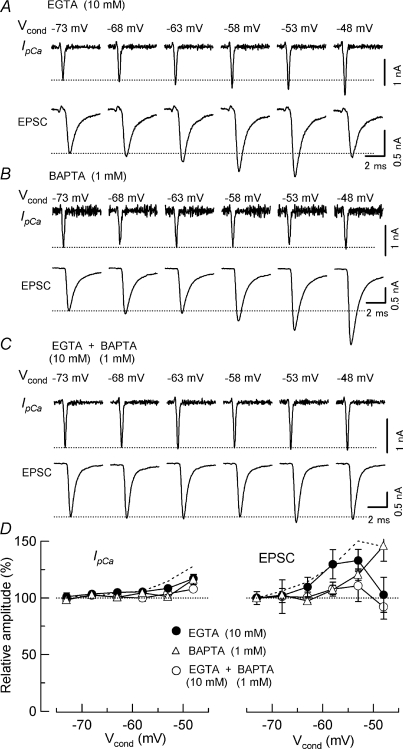

The strength and kinetics of Ca2+ buffers strongly influence the facilitation of transmitter release by residual Ca2+ (Blatow et al. 2003; Felmy et al. 2003). These parameters of Ca2+ buffers in the nerve terminals may change during postnatal development (Kandler & Friauf, 1993; Felmy & Schneggenburger, 2004), and may be different across synapses. Therefore, it seems important to evaluate the relative contribution of IpCa facilitation to synaptic facilitation under different Ca2+ buffer conditions. As previously reported (Awatramani et al. 2005), in the presence of 0.025 mm BAPTA, SDE was strong (213 ± 28%, n= 4, at −53 mV Vcond, Table 1), whereas in the presence of 0.5 mm EGTA, SDE was weaker with a facilitation of 154 ± 17% (n= 5, Table 1). We then increased intraterminal EGTA concentration to 10 mm. In this condition, with 1 mm kynurenate present in aCSF, the mean amplitude of EPSCs evoked by an AP waveform was 55% (1.2 ± 0.2 nA, n= 17) of that in 0.5 mm EGTA (2.2 ± 0.2 nA, n= 24), as previously reported for calyces of mice at a similar age (Fedchyshyn & Wang, 2005). In the presence of 10 mm EGTA, substantial SDE was still observed (Fig. 3D) with a magnitude of 123 ± 1.3% (at −53 mV Vcond, n= 4, Table 1). The mean contribution of IpCa facilitation to SDE, estimated by cancelling IpCa facilitation (Fig. 2), was 67%, 45% and 34% in the presence of 0.025 mm BAPTA, and 0.5 mm and 10 mm EGTA, respectively (Table 1). All-datum-point plots show that IpCa facilitation contributed to SDE by 20–80% in various Ca2+ buffer conditions (Fig. 4D), with an overall mean average contribution of 49 ± 5% (n= 13).

Figure 3. Blocking effects of EGTA and BAPTA on the facilitation of IpCa and EPSCs.

IpCa and EPSCs elicited by AP waveform Vtest following different Vcond. Calyceal terminals had been loaded with 10 mm EGTA (A), 1 mm BAPTA (B) or 1 mm BAPTA plus 10 mm EGTA (C), via presynaptic patch pipettes. D, summary data from 6–10 synapses. Relative changes of IpCa (left panel) and EPSCs (right panel) produced by Vcond (abscissa). Data with EGTA (10 mm, A), BAPTA (1 mm, B) and EGTA (10 mm) plus BAPTA (1 mm, C) are indicated by filled circles, open triangles and open circles, respectively. Dashed lines represent data with 0.5 mm EGTA (Fig. 1B) for comparison.

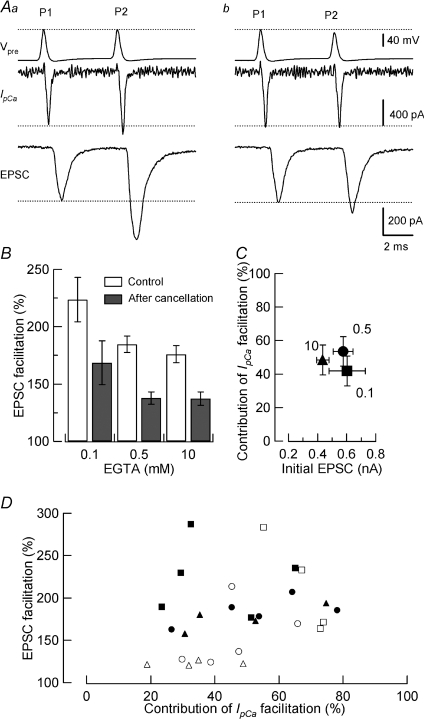

Figure 4. IpCa facilitation-dependent and -independent components of paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) of EPSCs.

Aa, PPF of EPSCs evoked by a pair of AP waveform-induced IpCa (P1, P2), with 5 ms ISI, in the presence of botulinum toxin E (BoNT/E; 20 nm) and 0.5 mm EGTA in the presynaptic pipette. Ab, IpCa facilitation was cancelled by adjusting the second command voltage (P2). B, PPF of EPSCs before (open columns) and after (filled columns) IpCa cancellation, in the presence of 0.1 mm, 0.5 mm, or 10 mm EGTA in the presynaptic pipette. C, the relationship between the mean percentage contribution of IpCa facilitation to PPF (ordinate) and mean amplitude of the initial EPSCs (P1, abscissa) in the presence of EGTA at 0.1 mm (square), 0.5 mm (circle) and 10 mm (triangle). D, all-points plot showing percentage contribution of IpCa facilitation (abscissa) vs. the magnitude of EPSC facilitation (ordinate). Open symbols represent SDE data at −53 mV Vcond (Fig. 2). Filled symbols represent PPF data. Presynaptic pipettes contained 0.5 mm EGTA (circles), 10 mm EGTA (triangles), 0.1 mm EGTA (filled squares), or 25 μm BAPTA (open squares). For SDE data, but not for PPF data, a weak correlation was observed between the SDE magnitude and percentage contribution of IpCa facilitation (r= 0.68, P < 0.01, Spearman's rank correlation test).

When BAPTA (1 mm) was loaded into the terminal instead of 0.5 mm EGTA (Fig. 3B), the mean EPSC amplitude was 44% of control (0.96 ± 0.3 nA, n= 7) as previously reported (Fedchyshyn & Wang, 2005), and SDE, by up to 15 mV depolarization, was strongly blocked (Fig. 3D). However, upon further depolarization, both IpCa and EPSCs showed clear facilitations (Fig. 3B and D), suggesting that loaded BAPTA might be saturated (Naraghi & Neher, 1997) by a massive increase in Ca2+ in the terminal upon strong depolarization (Supplemental Fig. 2A). Whilst higher concentrations of BAPTA abolish EPSCs in order to increase buffer strength without eliminating EPSCs, we loaded 1 mm BAPTA, together with 10 mm EGTA, into calyces. Under these conditions, the mean amplitude of EPSCs was 36% of control (0.8 ± 0.3 nA, n= 8), and depolarizing Vcond had little effect on EPSC facilitation throughout the Vcond range examined (Fig. 3C and D). EGTA and BAPTA also attenuated the facilitation of IpCa as previously reported (Cuttle et al. 1998).

IpCa facilitation-dependent and -independent components of PPF

Although IpCa facilitation has been suggested to underlie PPF (Inchauspe et al. 2004; Ishikawa et al. 2005), its contribution relative to other mechanisms has been estimated only recently in the presence of 75 μm EGTA in the rat calyx of Held (Müller et al. 2008). Using the cancellation method for IpCa facilitation (Fig. 2), we next estimated the contribution of IpCa facilitation to PPF, induced by paired AP waveform command pulses. Although paired-pulse stimulation depresses synaptic transmission in standard aCSF at the calyx of Held, lowering extracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]o) unmasks underlying synaptic facilitation (Barnes-Davies & Forsythe, 1995; Inchauspe et al. 2004; Ishikawa et al. 2005). However, a reduction in [Ca2+]o reduces IpCa facilitation (Cuttle et al. 1998) at the same time. To circumvent this problem, we utilized botulinum toxin E (BoNT/E). Like BoNT/A, BoNT/E cleaves SNAP-25 (Binz et al. 1994), thereby reducing the Ca2+ sensitivity of transmitter release (Capogna et al. 1997; Sakaba et al. 2005). The ensuing reduction of transmitter release probability will reduce synaptic vesicle depletion and postsynaptic AMPA receptor desensitization (Koike-Tani et al. 2008), and thereby will minimize synaptic depression. Given that the Ca2+ sensitivity of transmitter release rates, assessed from intraterminal Ca2+ uncaging, is unchanged during synaptic facilitation (Felmy et al. 2003), the Ca2+-dependent facilitation mechanism probably resides upstream of exocytotic machinery. On this assumption, cleaving SNAP-25 by BoNT/E will not affect the contribution of IpCa facilitation relative to other mechanisms underlying PPF. Fifteen to 35 min (n= 12) after whole-cell loading of BoNT/E (20–40 nm) into calyceal terminals, EPSCs evoked by presynaptic AP waveform command pulses declined to 10–20% of the initial amplitude. Concomitantly, the initially observed paired-pulse depression turned into facilitation of 185 ± 7.2% on average, at the inter-stimulus interval (ISI) of 5 ms in the presence of 0.5 mm EGTA in the nerve terminal (n= 5, Fig. 4Aa and B, Table 1). When IpCa facilitation was cancelled, PPF was reduced to 138 ± 5% (Fig. 4Ab and B), suggesting that the contribution of IpCa facilitation to PPF was 54% (Table 1). When the intraterminal Ca2+ buffer strength was weaker, with 0.1 mm EGTA, PPF was significantly greater (224 ± 19%, n= 5, P < 0.05, Fig. 4B, Table 1). This PPF magnitude is comparable to that (at 4 ms ISI) reported in low-Ca2+ solution at P8–10 rat calyces, loaded with 0.1 mm EGTA (Müller et al. 2007). When the intraterminal Ca2+ buffer strength was stronger, with 10 mm EGTA, PPF was similar to that in 0.5 mm EGTA (176 ± 7.5%, Fig. 4B, Table 1, P= 0.2), suggesting that PPF comprised EGTA-sensitive and -resistant components. The mean contribution of IpCa facilitation to PPF, estimated by cancelling IpCa facilitation (Fig. 4Ab), was 40%, 54% and 48% in the presence of EGTA at 0.1, 0.5 mm and 10 mm, respectively (Table 1), with these percentages having no correlation with the initial EPSC amplitude (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that IpCa facilitation makes major contributions to PPF under various Ca2+ buffer strengths. All-datum-point plots show that IpCa facilitation contributed to PPF by 20–80% in various Ca2+ buffer conditions (Fig. 4D), with an overall mean average contribution of 47 ± 5% (n= 14).

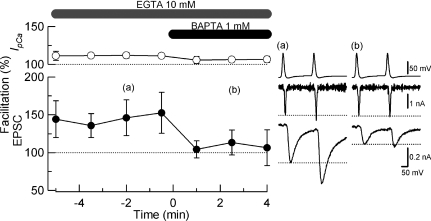

We next investigated whether the paired-pulse EPSC facilitation remaining in the presence of 10 mm EGTA (Fig. 4B) might be blocked by the addition of 1 mm BAPTA. When we infused 10 mm EGTA and 1 mm BAPTA into calyces using pipette perfusion (Hori et al. 1999), within 1 min of infusion the EPSC amplitude decreased to 57% (n= 5) and the PPF of EPSCs declined from 146% (averaged from 0.5–5 min before BAPTA infusion) to near the baseline (105 ± 4.1% averaged from 1–4 min after BAPTA infusion, Fig. 5). Concomitantly, IpCa facilitation decreased from 112% to 105%. These results, together with those for SDE (Fig. 3), suggest that the mechanisms underlying PPF and SDE reside in the immediate vicinity of VGCCs, where only the fast Ca2+ buffers such as BAPTA can reach.

Figure 5. Block of PPF by intraterminal infusion of BAPTA BAPTA.

(1 mm) was infused into presynaptic terminals, using pipette perfusion, during whole-cell recording. The presynaptic patch pipette contained 10 mm EGTA and BoNT/E (20 nm). Infusion of BAPTA blocked PPF (filled circles) and IpCa facilitation (open circles). Circles and bars represent mean amplitudes and s.e.m. (n = 5) of three data sampled every 30 s. Data points and bars represent mean and s.e.m. from 5 terminals. Sample records before (a) and after (b) BAPTA infusion are shown in the right panel.

The effect of presynaptic depolarization on transmitter release at intact synapses

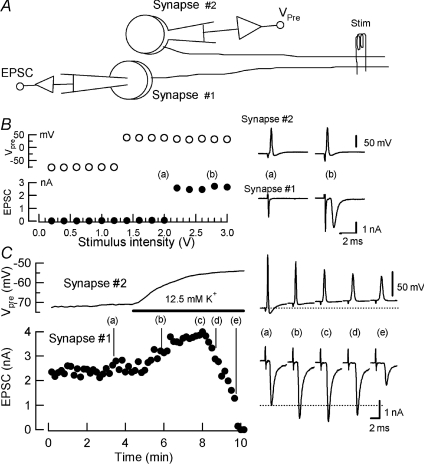

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings have enabled us to dissect the mechanisms underlying facilitation and depression of transmitter release following presynaptic depolarization. It remains unknown, however, how these mechanisms are involved in facilitation and depression of transmitter release at intact synapses. To investigate this issue, we performed simultaneous whole-cell recordings from a MNTB principal neuron at one synapse (#1) and from a presynaptic terminal of another synapse (#2, Fig. 6). The lack of direct connection between the two synapses was ascertained by distinct minimal stimulus intensities required for generating presynaptic APs (Synapse #2) and EPSCs (Synapse #1, Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. The effect of sustained presynaptic depolarization on synaptic transmission at intact synapses.

A, recording and stimulation scheme. EPSCs were evoked by afferent fibre stimulation (Stim), and recorded from a medial nucleus of trapezoid body (MNTB) principal cell (Synapse #1). Presynaptic membrane potential (Vpre) was monitored from a nearby calyceal terminal of a different synapse (Synapse #2). B, all-or-none generation of presynaptic action potentials (APs, Vpre, open circles, Synapse #2) and EPSCs (filled circles, Synapse #1) at different thresholds (stimulus intensities in abscissa). Sample traces show presynaptic APs (Synapse #2) and EPSCs (Synapse #1) evoked by different stimulus intensities (a and b). C, bath application of 12.5 mm[K+] solution (bar) depolarized presynaptic terminal (Synapse #2) and caused an increase (sample records at b and c), followed by a decrease (d and e) of the EPSC amplitude (Synapse #1).

Raising extracellular K+ concentration ([K+]o) from 3 mm to 12.5 mm gradually depolarized presynaptic terminals and depressed presynaptic AP amplitude (Synapse #2, Fig. 6C). Concomitantly the EPSC amplitude (Synapse #1) increased and the magnitude of this SDE reached a peak of 155 ± 6% (n= 5) when the presynaptic membrane potential reached around −57 mV (Figs 6C and 8B). Thereafter, EPSCs declined in amplitude and eventually became undetectable.

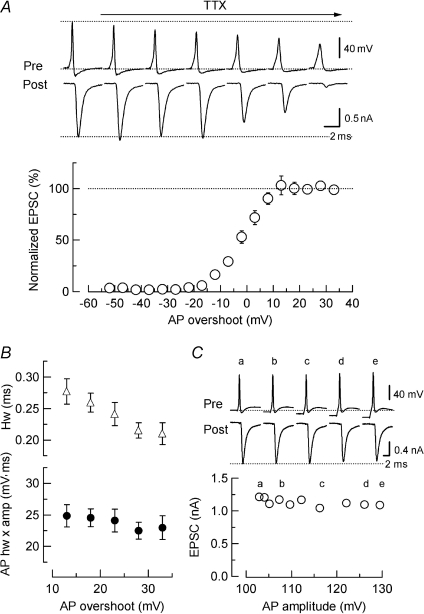

Figure 8. Simultaneous occurrence of facilitation and depression of transmitter release during sustained presynaptic depolarization.

A, the AP overshoot during presynaptic depolarization (Vpre, presynaptic membrane potentials, abscissa) at Synapse #2. A dotted line indicates the level at which EPSCs start to decline during TTX application (Fig. 7A). B, the relative EPSC amplitude (Synapse #1, ordinate) during K+-induced presynaptic depolarization (Vpre at Synapse #2 in abscissa). Summary data from 5 experiments (curve a). A dashed line represents control EPSC amplitude before K+ application. Open circles (curve b) indicate EPSC amplitudes estimated from AP size reduction (Fig. 8). Open triangles indicate EPSC amplitudes obtained by subtracting data b from data a, representing components of EPSCs facilitated by presynaptic depolarization.

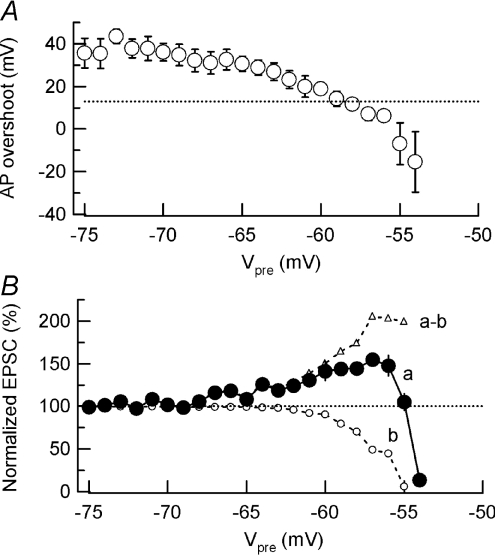

As AP amplitude declined during presynaptic depolarization (Fig. 6C), we asked how the diminishment of presynaptic AP amplitude could affect transmitter release. To this end, we evoked EPSCs by presynaptic APs elicited by current injection, and gradually blocked voltage-gated Na+ channels using tetrodotoxin (TTX) at a low concentration (5–50 nm, Katz & Miledi, 1967). After TTX application, presynaptic AP amplitude gradually declined. Unexpectedly, however, the EPSC amplitude remained similar until the AP overshoot declined below 13 mV (Fig. 7A). As the decline of AP amplitude was accompanied by an increase in AP duration (Fig. 7B, see also Borst & Sakmann, 1999), and an increase in AP duration enhances transmitter release (Ishikawa et al. 2003; Yang & Wang, 2006), AP broadening might compensate for the reduction in AP overshoot for transmitter release. To examine this possibility, we measured the half-width of the AP (duration at 50% of AP amplitude) and multiplied it by the amplitude of the AP. As shown in Fig. 7B, these values were similar for APs having an overshoot greater than 13 mV, suggesting that reduced AP amplitude was compensated by AP broadening, thereby maintaining a similar amount of transmitter release. This safety margin is also supported by the voltage dependence of VGCC activation, which reaches a maximal above 10 mV (Forsythe et al. 1998; Ishikawa et al. 2005). When presynaptic AP overshoot became smaller than 13 mV, the EPSC amplitude steeply declined, with a slope of 72 ± 7% (n= 7) for a 10 mV reduction of presynaptic AP amplitude, which is comparable to that reported at the squid giant synapse (86% (10 mV)−1, Katz & Miledi, 1967).

Figure 7. The relationship between presynaptic AP amplitude and EPSC amplitude.

In simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic recordings, EPSCs were evoked by presynaptic APs (elicited by 1 ms depolarizing current injection). Presynaptic APs and EPSCs sampled from different epochs after bath application of TTX (10 nm) are shown in the upper panel. The lower panel shows the relationship between the relative EPSC amplitude (ordinate, normalized to the amplitude before TTX application, open circles) and absolute amplitude of presynaptic AP overshoot (abscissa, mV) during TTX application. Data derived from 7 synapses. The EPSC amplitude remained unchanged (initial amplitude indicated by a dashed line) until the AP overshoot declined below 10 mV. Presynaptic resting potential was −78 ± 1 mV (n= 7). B, half-width (open triangles) and half-width multiplied by amplitude (filled circles) of APs having 13–33 mV overshoot. C, no effect of presynaptic hyperpolarization on the EPSC amplitude (ordinate) at a calyx of Held synapse. Presynaptic AP amplitude (abscissa) increased when the nerve terminal was hyperpolarized by DC current injection. The presynaptic resting potential before current injection was −78 mV. The initial levels of presynaptic membrane potential (Pre, a) and peak EPSC amplitude (Post, a) are indicated by dotted lines. Essentially the same results were obtained at another synapse in mice and at 8 synapses in rats.

At invertebrate synapses, presynaptic hyperpolarization facilitates (Hagiwara & Tasaki, 1958; Kusano et al. 1967), or inhibits (Shapiro et al. 1980; Kretz et al. 1986) transmitter release. By contrast, at the calyces of Held in mice (Fig. 7C) and rats (data not shown), presynaptic hyperpolarization by current injection had no effect on the EPSC amplitude, although it increased the AP amplitude up to 130 mV. This is probably because of a lack of resting-state inactivation in presynaptic VGCCs (Forsythe et al. 1998; Ishikawa et al. 2005) and predominant presence of non-inactivating K+ channels (Ishikawa et al. 2003) at the calyx of Held presynaptic terminal. In the absence of resting-state inactivation, the open probability of VGCCs gated by APs would not be increased by presynaptic hyperpolarization.

During the bath application of high [K+]o solution (Fig. 6), presynaptic AP overshoot declined to around 10 mV when the presynaptic terminal was depolarized to −58 mV, and continued to decline upon further depolarization (Fig. 8A). The magnitude of EPSC depression expected from the AP size diminution was estimated from Fig. 7A and plotted in Fig. 8B (curve b). Clearly, concomitant facilitation of transmitter release by presynaptic depolarization masks this depression (Fig. 8B) (curve a). Assuming that facilitation and depression linearly summate for the EPSC amplitude (Dittman et al. 2000), the EPSC facilitation occurring in high [K+]o solution, in the virtual absence of AP size diminution, could be estimated from a difference (a – b) between the EPSC amplitude (a) and that predicted from presynaptic AP diminution (b). This magnitude of facilitation represents the lower limit, given that RRP reduction might additionally be involved (see below).

Mechanisms underlying EPSC depression caused by presynaptic depolarization

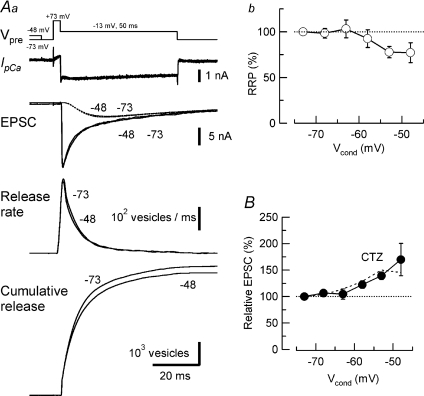

Presynaptic depolarization has bidirectional effects on synaptic transmission by facilitating and depressing transmitter release. At many synapses, these effects are mixed, with one effect masking the other. We next investigated mechanisms underlying depression of transmitter release caused by a sustained depolarization. Following presynaptic depolarization by 25 mV (Vcond, −48 mV) for 1 s, the EPSC amplitude was modulated by both facilitation and depression, the latter becoming evident when IpCa facilitation was cancelled (Fig. 2C). As previously demonstrated by Awatramani et al. (2005) a sustained presynaptic depolarization for 1 s caused a tonic increase in intraterminal Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i; Supplemental Fig. 2A), which has been attributed to Ca2+ entry through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs; Awatramani et al. 2005). Concomitantly, the frequency of quantal EPSCs (qEPSCs) increased in a non-linear proportion to the magnitude of presynaptic depolarization (Supplemental Fig. 2B), as previously shown at the neuromuscular junction (del Castillo & Katz, 1954), and at the calyx of Held (Sahara & Takahashi, 2001). In such conditions, releasable synaptic vesicles in a calyx might be depleted. Using deconvolution analysis (Sakaba & Neher, 2001), we estimated the size of the readily releasable pool (RRP) of synaptic vesicles before and after Vcond (Fig. 9Aa). At −73 mV holding potential, the RRP size of the calyx of Held synapse in P10–12 mice was estimated to be 5300, which is twice as large as that estimated for P8–10 rats by the same method (2408 before pool recovery correction; Sakaba & Neher, 2001). After −48 mV Vcond for 1 s, the RRP size was reduced to 77 ± 11% (n= 4, Fig. 9Ab), whereas Vcond below −63 mV had no such effect (Fig. 9Ab), implying that RRP could be fully replenished during presynaptic depolarization by 7 mV or less.

Figure 9. Pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms underlying EPSC depression caused by presynaptic depolarization.

Aa, estimation of the readily releasable pool (RRP) size of synaptic vesicles before (−73 mV) and after depolarizing Vcond (1 s, voltage protocol in the top row). Sample records on the second and third rows show IpCa and EPSCs after Vcond to −48 mV and −73 mV (superimposed). Traces in the fourth row show release rates, calculated from the deconvolution method at different Vcond (superimposed). In the bottom row, RRP size was estimated from the cumulative number of quanta released during a test pulse to −13 mV (50 ms, top trace) before (−73 mV) and after Vcond to −48 mV for 1 s (superimposed). The aCSF solution contained kynurenate (1 mm), but did not contain cyclothiazide (CTZ). Dotted lines superimposed on EPSC traces indicate AMPA receptor currents caused by residual glutamate in the synaptic cleft (Sakaba & Neher, 2001) at −48 mV and −73 mV Vcond. B, contribution of postsynaptic AMPA receptor desensitization to EPSC depression assessed by CTZ (100 μm) at various Vcond. Ab, presynaptic depolarization-induced reduction in the RRP size at various Vcond. Data points derived from 4 synapses. Control SDE without CTZ (Fig. 1B, dashed line) is superimposed on the data with CTZ.

Another mechanism, which can contribute to synaptic depression by presynaptic depolarization is the desensitization of postsynaptic AMPA receptors (AMPARs) by the transmitter glutamate released during presynaptic depolarization (Supplemental Fig. 2B). However, blocking AMPAR desensitization by cyclothiazide (CTZ, 100 μm; Trussell et al. 1993; Yamada & Tang, 1993; Koike-Tani et al. 2005, 2008), had only a minor effect on the magnitude of EPSCs after 1 s Vcond up to −48 mV (Fig. 9B), suggesting that AMPARs might rapidly recover from desensitization by quantal glutamate. Thus, AMPAR desensitization does not seem to make an essential contribution to synaptic depression caused by 12.5 mm[K+]o (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Using simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic recordings at the calyx of Held synapse, we have dissected mechanisms by which transmitter release is facilitated or depressed by presynaptic depolarization. Voltage-clamp cancellation of IpCa facilitation revealed that its contribution to the facilitation of transmitter release is nearly 50% under various intraterminal Ca2+ buffer concentrations. Importantly, intraterminal EGTA only partially blocked SDE or PPF, even at 10 mm, and addition of the fast-binding Ca2+ buffer BAPTA was required to completely block them. Residual Ca2+ has often been represented by volume-averaged Ca2+ concentration dynamics in the presynaptic terminal (Dittman et al. 2000; Müller et al. 2007). Our results suggest, however, that residual Ca2+ in the VGCC microdomain, which is inaccessible by conventional Ca2+ measurements, also plays an essential role in synaptic facilitation.

Mechanisms underlying facilitation of transmitter release

At the calyx of Held, multiple mechanisms underlie the facilitation of transmitter release induced by presynaptic depolarization. These include linear summation of residual bulk Ca2+ (Katz & Miledi, 1967; Felmy et al. 2003), putative saturation of endogenous Ca2+ buffers (Blatow et al. 2003; Felmy et al. 2003) and IpCa facilitation (Borst & Sakmann, 1998b; Cuttle et al. 1998). At intact nerve terminals, the magnitude of synaptic facilitation, as well as the relative contribution of distinct facilitation mechanisms, depends upon the strength and binding kinetics of endogenous Ca2+ buffers. In whole-cell recording without exogenous Ca2+ buffer at immature calyces of Held, where endogenous mobile Ca2+ buffers are mostly washed out (Müller A et al. 2005; Müller M et al. 2007), linear summation of residual Ca2+ to facilitation reportedly accounts for 30% of facilitation of transmitter release induced by sustained depolarization (Felmy et al. 2003). Both SDE and PPF were greater than 200% when the intraterminal Ca2+ buffer strength was low with 25 μm BAPTA or 0.1 mm EGTA (Table 1; see also Awatramani et al. 2005; Müller et al. 2007). In such a weak Ca2+ buffer condition, IpCa facilitation accounted for 67% of SDE and 40% of PPF (Table 1; see also Müller et al. 2008), suggesting that this mechanism, together with linear summation of residual bulk Ca2+, comprises the main mechanisms underlying SDE and PPF. In strong Ca2+ buffer conditions, with 10 mm EGTA in presynaptic terminals, SDE was maximally 123% (at −53 mV Vcond, Table 1, Fig. 3) and PPF was 176% (at 5 ms ISI, Table 1, Fig. 4B), both of which could essentially be abolished by addition of BAPTA (1 mm, Figs 3 and 5). BAPTA has a similar Ca2+-binding affinity to EGTA, but is two orders of magnitude faster in Ca2+-binding on-rate than EGTA (Naraghi, 1997). Therefore, SDE and PPF, observed in 10 mm EGTA, must be produced by mechanisms residing near VGCCs. In 10 mm EGTA, IpCa facilitation accounted for 34% of SDE and 48% of PPF (Table 1). Mechanisms underlying the remaining fractions may include saturation of immobile buffer localized near VGCCs (Matveev et al. 2004). It should be noted that intraterminal EGTA at 10 mm attenuated facilitations of both IpCa (Fig. 3D, Table 1; see also Cuttle et al. 1998) and transmitter release (Figs 3 and 4, Table 1), suggesting that residual bulk Ca2+ contributes to facilitations of IpCa and transmitter release. Intraterminal EGTA at 10 mm also reduces the EPSC amplitude by selectively blocking transmitter release from vesicles loosely coupled with VGCCs at immature mice calyceal synapses (Table 1; Fedchyshyn & Wang, 2005). Thus, facilitation of transmitter release observed in the presence of 10 mm EGTA (Figs 3, 4 and 5; Table 1) must occur selectively in vesicles tightly coupled with VGCCs.

The strength of endogenous Ca2+ buffer is estimated to be equivalent to 0.1–0.2 mm EGTA at the calyx of Held in immature rats and mice before hearing onset (Borst & Sakmann, 1996; Müller et al. 2007), but it may increase during postnatal development, as the expression of parvalbumin and calretinin increases in the calyx terminal (Kandler & Friauf, 1993; Felmy & Schneggenburger, 2004). Furthermore, spatial distribution of presynaptic VGCCs is reformed during postnatal development (Fedchyshyn & Wang, 2005) towards less overlap of Ca2+ transients between Ca2+ microdomains (Y. Nakamura, D. DiGregorio, A. Silver & T. Takahashi, unpublished observations). These developmental changes may underlie developmental declines of post-tetanic potentiation (Korogod et al. 2005), as well as of CaM-dependent IpCa modulations (Nakamura et al. 2008). Likewise, they will reduce the contribution of residual bulk Ca2+ to synaptic facilitation. By contrast, significant contribution of IpCa facilitation to PPF and SDE, for a wide range of Ca2+ buffer strength (Fig. 4D, Table 1), suggests that it remains as a major facilitation mechanism throughout postnatal development.

At the hippocampal mossy fibre terminals, electrotonically propagated postsynaptic potential facilitates transmitter release by depolarizing the nerve terminal (Alle & Geiger, 2006; Scott et al. 2008). As this synaptic facilitation is resistant to 10 mm EGTA, and unaccompanied by an increase in Ca2+ signals, it was suggested to arise from a Ca2+-independent mechanism (Alle & Geiger, 2006). Furthermore, given that a membrane-permeable BAPTA analogue, at a presumable intraterminal concentration of 0.5–1 mm, failed to block this synaptic facilitation, it was concluded that presynaptic Ca2+ change is uninvolved in the synaptic facilitation (Scott et al. 2008). Likewise, at the calyx of Held, intraterminal loading of EGTA, even at 10 mm, or 1 mm BAPTA alone, could not block SDE or PPF, but remaining facilitations were abolished by a combined application of 10 mm EGTA and 1 mm BAPTA (Figs 3 and 5). Therefore, the issue of Ca2+ dependence on the facilitation of transmitter release by hippocampal mossy fibre terminal depolarization (Alle & Geiger, 2006; Scott et al. 2008) remains open.

Mechanisms underlying depression of transmitter release

At intact calyces of Held, during sustained mild (< 20 mV) presynaptic depolarization in high [K+]o solution, SDE was followed by a depression of transmitter release (Fig. 6). During presynaptic depolarization at intact synapses, presynaptic AP overshoot underwent a decline, owing to inactivation of voltage-gated Na+ channels. This mechanism, together with the RRP size reduction (Fig. 9A), depresses transmitter release during a mild depolarization (Fig. 6). In contrast, in the paired-pulse stimulation protocol, presynaptic APs undergo little change in amplitude and shape (Wang & Kaczmarek, 1998), whereas the RRP depletion and AMPAR desensitization contribute to paired-pulse depression in a release probability-dependent manner (Koike-Tani et al. 2008). Thus, whilst multiple mechanisms potentially operate for facilitation and depression of transmitter release, the magnitude of presynaptic depolarization, and intraterminal Ca2+ buffer conditions are important determinants of the direction of presynaptic modulation, as well as of the relative contributions of individual mechanisms involved in presynaptic modulations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, Sports and Technology (Japan). We thank Mark Farrant and Erwin Neher for comments on an earlier version of this paper, and Takeshi Sakaba for technical advice in deconvolution analysis.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- aCSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- AMPAR

AMPA receptor

- AP

action potential

- BoNT/A

botulinum toxin A

- BoNT/E

botulinum toxin E

- CaM

calmodulin

- [Ca2+]o

extracellular Ca2+ concentration

- CTZ

cyclothiazide

- eEPSC

action potential-evoked EPSC

- IpCa

presynaptic Ca2+ current

- ISI

inter-stimulus interval

- [K+]o

extracellular K+ concentration

- MNTB

medial nucleus of trapezoid body

- NCS-1

neuronal Ca2+ sensor 1

- P

postnatal day

- PPF

paired-pulse facilitation

- qEPSC

quantal EPSC

- QX-314 Cl

N-(2,6-diethylphenylcarbamoylmethyl)-triethylammonium chloride

- RRP

readily releasable pool

- SDE

small depolarization-dependent enhancement

- SNAP-25

synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa

- Vcond

conditioning pulse

- Vtest

test pulse

- VGCC

voltage-gated Ca2+ channel

Author contributions

T.H. and T.T. designed the experiments, wrote the manuscript and approved the final manuscript. T.H. performed experiments and data analysis. T.T. and T.H. participated in data interpretations.

Supplemental material

References

- Alle H, Geiger JRP. Combined analog and action potential coding in hippocampal mossy fibers. Science. 2006;311:1290–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.1119055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atluri PP, Regehr WG. Determinants of the time course of facilitation at the granule cell to Purkinje cell synapse. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5661–5671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05661.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awatramani GB, Price GD, Trussell LO. Modulation of transmitter release by presynaptic resting potential and background calcium levels. Neuron. 2005;48:109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Davies M, Forsythe ID. Pre- and postsynaptic glutamate receptors at a giant excitatory synapse in rat auditory brainstem slices. J Physiol. 1995;488:387–406. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram R, Sherman A, Stanley EF. Singledomain/bound calcium hypothesis of transmitter release and facilitation. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:1919–1931. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.5.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binz T, Blasi J, Yamasaki S, Baumeister A, Link E, Sudhof TC, Jahn R, Niemann H. Proteolysis of SNAP-25 by types E and A botulinal neurotoxins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1617–1620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatow M, Caputi A, Burnashev N, Monyer H, Rozov A. Ca2+ buffer saturation underlies paired pulse facilitation in calbindin-D28k-containing terminals. Neuron. 2003;38:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JGG, Sakmann B. Calcium influx and transmitter release in a fast CNS synapse. Nature. 1996;383:431–434. doi: 10.1038/383431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JGG, Sakmann B. Calcium current during a single action potential in a large presynaptic terminal of the rat brainstem. J Physiol. 1998a;506:143–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.143bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JGG, Sakmann B. Facilitation of presynaptic calcium currents in the rat brainstem. J Physiol. 1998b;513:149–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.149by.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JGG, Sakmann B. Effect of changes in action potential shape on calcium currents and transmitter release in a calyx-type synapse of the rat auditory brainstem. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999;354:347–355. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capogna M, McKinney RA, O’Connor V, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Ca2+ or Sr2+ partially rescues synaptic transmission in hippocampal cultures treated with botulinum toxin A and C, but not tetanus toxin. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7190–7202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07190.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton MP, Smith SJ, Zucker RS. Role of presynaptic calcium ions and channels in synaptic facilitation and depression at the squid giant synapse. J Physiol. 1982;323:173–193. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Jahr CE. Dendritic NMDA receptors activate axonal calcium channels. Neuron. 2008;60:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuttle MF, Tsujimoto T, Forsythe ID, Takahashi T. Facilitation of the presynaptic calcium current at an auditory synapse in rat brainstem. J Physiol. 1998;512:723–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.723bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Castillo J, Katz B. Changes in end-plate activity produced by pre-synaptic polarization. J Physiol. 1954;124:586–604. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaria CD, Soong TW, Alseikhan BA, Alvania RS, Yue DT. Calmodulin bifurcates the local Ca2+ signal that modulates P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. Nature. 2001;411:484–489. doi: 10.1038/35078091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittman JS, Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG. Interplay between facilitation, depression, and residual calcium at three presynaptic terminals. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1374–1385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01374.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedchyshyn MJ, Wang L-Y. Developmental transformation of the release modality at the calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4131–4140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0350-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felmy F, Neher E, Schneggenburger R. Probing the intracellular calcium sensitivity of transmitter release during synaptic facilitation. Neuron. 2003;37:801–811. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felmy F, Schneggenburger R. Developmental expression of the Ca2+ binding proteins calretinin and parvalbumin at the calyx of Held of rats and mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1473–1482. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe ID, Tsujimoto T, Barnes-Davies M, Cuttle MF, Takahashi T. Inactivation of presynaptic calcium current contributes to synaptic depression at a fast central synapse. Neuron. 1998;20:797–807. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara S, Tasaki I. A study on the mechanism of impulse transmission across the giant synapse of the squid. J Physiol. 1958;143:114–137. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1958.sp006048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori T, Takai Y, Takahashi T. Presynaptic mechanism for phorbol ester-induced synaptic potentiation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7262–7267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07262.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inchauspe CG, Martini FJ, Forsythe ID, Uchitel OD. Functional compensation of P/Q by N-type channels blocks short-term plasticity at the calyx of Held presynaptic terminal. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10379–10383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2104-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T, Kaneko M, Shin H-S, Takahashi T. Presynaptic N-type and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels mediating synaptic transmission at the calyx of Held of mice. J Physiol. 2005;568:199–209. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T, Nakamura Y, Saitoh N, Li W-B, Iwasaki S, Takahashi T. Distinct roles of Kv1 and Kv3 potassium channels at the calyx of Held presynaptic terminal. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10445–10453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-32-10445.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandler K, Friauf E. Pre- and postnatal development of efferent connections of the cochlear nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993;328:161–184. doi: 10.1002/cne.903280202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Miledi R. A study of synaptic transmission in the absence of nerve impulses. J Physiol. 1967;192:407–436. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Miledi R. The role of calcium in neuromuscular facilitation. J Physiol. 1968;195:481–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike-Tani M, Saitoh N, Takahashi T. Mechanisms underlying developmental speeding in AMPA-EPSC decay time at the calyx of Held. J Neurosci. 2005;25:199–207. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3861-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike-Tani M, Kanda T, Saitoh N, Yamashita T, Takahashi T. Involvement of AMPA receptor desensitization in short-term synaptic depression at the calyx of Held in developing rats. J Physiol. 2008;586:2263–2275. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korogod N, Lou X, Schneggenburger R. Presynaptic Ca2+ requirements and developmental regulation of posttetanic potentiation at the calyx of Held. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5127–5137. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1295-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretz R, Shapiro E, Bailey CH, Chen BM, Kandel ER. Presynaptic inhibition produced by an identified presynaptic inhibitory neuron. II. Presynaptic conductance changes caused by histamine. J Neurophysiol. 1986;55:131–146. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusano K, Livengood DR, Werman R. Correlation of transmitter release with membrane properties of the presynaptic fiber of the squid giant synapse. J Gen Physiol. 1967;50:2579–2601. doi: 10.1085/jgp.50.11.2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Kocsis JD, Ransom BR, Waxman SG. Modulation of parallel fibre excitability by postsynaptically mediated changes in extracellular potassium. Science. 1981;214:339–341. doi: 10.1126/science.7280695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matveev V, Zucker RS, Sherman A. Facilitation through buffer saturation: Constraints on endogenous buffering properties. Biophys J. 2004;86:2691–2709. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74324-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongillo G, Barak O, Tsodyks M. Synaptic theory of working memory. Science. 2008;319:1543–1546. doi: 10.1126/science.1150769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller A, Kukley M, Stausberg P, Beck H, Müller W, Dietrich D. Endogenous Ca2+ buffer concentration and Ca2+ microdomains in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:558–565. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3799-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M, Felmy F, Schwaller B, Schneggenburger R. Parvalbumin is a mobile presynaptic Ca2+ buffer in the calyx of Held that accelerates the decay of Ca2+ and short-term facilitation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2261–2271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5582-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M, Felmy F, Schneggenburger R. A limited contribution of Ca2+ current facilitation to paired-pulse facilitation of transmitter release at the rat calyx of Held. J Physiol. 2008;586:5503–5520. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.155838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Yamashita T, Saitoh N, Takahashi T. Developmental changes in calcium/calmodulin-dependent inactivation of calcium currents at the rat calyx of Held. J Physiol. 2008;586:2253–2261. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naraghi M. T-jump study of calcium binding kinetics of calcium chelators. Cell Calcium. 1997;22:255–268. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naraghi M, Neher E. Linearized buffered Ca2+ diffusion in microdomains and its implications for calculation of [Ca2+] at the mouth of a calcium channel. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6961–6973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-06961.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahara Y, Takahashi T. Quantal components of the excitatory postsynaptic currents at a rat central auditory synapse. J Physiol. 2001;536:189–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T, Neher E. Quantitative relationship between transmitter release and calcium current at the calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2001;21:462–476. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00462.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T, Stein A, Jahn R, Neher E. Distinct kinetic changes in neurotransmitter release after SNARE protein cleavage. Science. 2005;309:491–494. doi: 10.1126/science.1112645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott R, Ruiz A, Henneberger C, Kullmann DM, Rusakov DA. Analog modulation of mossy fibre transmission is uncoupled from changes in presynaptic Ca2+ J Neurosci. 2008;28:7765–7773. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1296-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro E, Castellucci VF, Kandel ER. Presynaptic membrane potential affects transmitter release in an identified neuron in Aplysia by modulating the Ca2+ and K+ currents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:629–633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.1.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer W, Lux HD. Presynaptic depolarization and extracellular potassium in the cat lateral geniculate nucleus. Brain Res. 1973;64:17–33. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y-G, Schlumpberger T, Kim T-S, Lueker M, Zucker RS. Effects of mobile buffers on facilitation: Experimental and computational studies. Biophys J. 2000;78:2735–2751. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(00)76819-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trussell LO, Zhang S, Raman IM. Desensitization of AMPA receptors upon multiquantal neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1993;10:1185–1196. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90066-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto T, Jeromin A, Saitoh N, Roder JC, Takahashi T. Neuronal calcium sensor 1 and activity-dependent facilitation of P/Q-type calcium currents at presynaptic nerve terminals. Science. 2002;295:2276–2279. doi: 10.1126/science.1068278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turecek R, Trussell LO. Presynaptic glycine receptors enhance transmitter release at a mammalian central synapse. Nature. 2001;411:587–590. doi: 10.1038/35079084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L-Y, Kaczmarek LK. High-frequency firing helps replenish the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles. Nature. 1998;394:384–388. doi: 10.1038/28645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada KA, Tang C-M. Benzothiadiazides inhibit rapid glutamate receptor desensitization and enhance glutamatergic synaptic currents. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3904–3915. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-03904.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada WM, Zucker RS. Time course of transmitter release calculated from simulations of a calcium diffusion model. Biophys J. 1992;61:671–682. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81872-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y-M, Wang L-Y. Amplitude and kinetics of action potential-evoked Ca2+ current and its efficacy in triggering transmitter release at the developing calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5698–5708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4889-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Ann Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.