Abstract

Colorectal cancer immunotherapy is limited by the paucity of available target antigens fulfilling the necessary criteria of tumor‐specificity, sufficient immunogenicity and universal association with disease. A novel class of immune targets, cancer mucosa antigens (CMAs), whose expression normally is confined to mucosae but maintained during neoplastic transformation, promises to overcome these imitations, enjoying the advantage of immune compartmentalization, preventing autoimmune disease, while permitting therapeutic anti‐tumor responses. Indeed, therapeutic immunization against the model CMA guanylyl cyclase c (GCC) extends survival in mouse models of established parenchymal colorectal cancer metastases with antitumor efficacy superior to currently available antigens. Here adjuvanation of therapeutic antitumor immunity to GCC was explored employing the cytokines IL‐2 and GM‐CSF in a mouse model of metastatic colorectal cancer. Combining plasmids expressing murine IL‐2 or GM‐CSF with recombinant viral vector immunization to GCC enhanced antitumor efficacy beyond viral vector immunization alone. These studies support the incorporation of IL‐2 and GM‐CSF in CMA‐targeted immunization regimens for established colorectal cancer metastases.

Keywords: cancer mucosa antigens, guanylyl cyclase C, colorectal cancer, cancer immunotherapy, GM‐CSF, IL‐2

Introduction

Colorectal cancer immunotherapy is limited by the paucity of available target antigens fulfilling the necessary criteria of tumor‐specificity, sufficient immunogenicity and universal association with disease. 1 We have identified a novel class of immune targets, cancer mucosa antigens, whose expression normally is confined to mucosae but continue to be expressed after epithelial cells undergo neoplastic transformation. 2 , 3 These proteins enjoy the advantage of immune compartmentalization in which mucosal antigens exhibit incomplete tolerance in the central compartment, permitting therapeutic antitumor responses. 2 , 3 However, the absence of immunological cross‐talkbetween central and mucosal compartments ensures that therapeutic antitumor responses do not extend to mucosal autoimmune disease. 2 , 3 Indeed, guanylyl cyclase C (GCC) is a model intestinal cancer mucosa antigen, and therapeutic immunization employing recombinant viral vectors extends survival in mouse models of established parenchymal colorectal cancer metastases with antitumor efficacy superior to currently available antigens. 4

IL‐2 and GM‐CSF are the most extensively characterized cytokine adjuvants for antitumor therapy. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 IL‐2 promotes proliferation and differentiation of T cells, enhances effector activities of natural killer cells, and enhances the efficacy of viral‐based immunization. 5 GM‐CSF enhances recruitment of antigen presenting cells to sites of immunization, potentiates activities of T cells, and synergizes with IL‐2‐supported immune responses induced by virally‐encoded self antigens. 7 , 8 IL‐2 and GM‐CSF have been incorporated in antitumor vaccines, including those for colorectal cancer, in animals and humans. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Here, we examine adjuvanation of therapeutic GCC‐specific immunization by GM‐CSF and IL‐2 in a mouse model of metastatic colorectal cancer.

Methods

Mice and viruses

BALB/c mice were obtained from the NCI Animal Production Program (Frederick, MD, USA). GCCECD and control (LacZ) adenovirus (AV) and vaccinia virus (VV) were described previously. 4 Animal protocols were approved by the Thomas Jefferson University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Metastatic tumors and immunization

To establish lung metastases, 5 × 105 CT26‐GCCTM cells, expressing the membrane‐bound extracellular domain of GCC, were administered via tail vein injection (day 0). 4 Mice were then immunized IM with 1 × 108 IFU of control or GCCECD AV on day 3 and with 1 × 107 PFU VV on day 10. Plasmids (10 μg) expressing mouse GM‐CSF (pUMVCl‐mGM‐CSF) or IL‐2 (pUMVC3‐mIL‐2) (Aldevron, Fargo, ND, USA) or an equal volume of PBS (control) were mixed with the viruses and co‐injected with the prime and boost. Mice were then euthanized on day 15 and metastases were enumerated.

Results

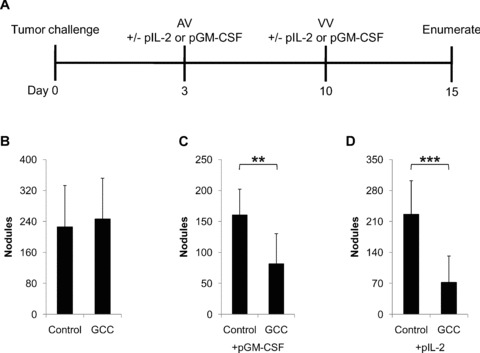

While GCC‐specific immunization effectively extended the survival of mice with established lung metastases, 4 the working hypothesis suggests that cytokine adjuvanation will enhance immune responses and antitumor efficacy. Here, the effect of cytokines on GCC‐specific antitumor immunity against established metastatic tumors was explored. BALB/c mice were challenged with the GCC‐expressing colorectal cancer cell line CT26‐GCCTM to establish lung metastases. A suboptimal immunization regimen was administered employing AV 3 days after tumor cell challenge and VV 7 days after AV ( Figure 1A ). Consistent with established principles, in which vaccine boosts are most effective when administered during the memory phase of primed immune responses, GCC‐targeted antitumor efficacy was suboptimal when boosts were administered <28 days following prior immunization ( Figure 1B and data not shown). However, co‐administration of 10 μg of plasmid DNA encoding mouse GM‐CSF reduced nodules approximately 50% (p < 0.01; Figure 1C ), while addition of mouse IL‐2‐expressing plasmid reduced nodules approximately 75% (p < 0.001; Figure 1D ) compared to mice immunized with control viruses and cytokines.

Figure 1.

Augmentation of therapeutic GCC‐specific anti‐tumor immunity by GM‐CSF and IL‐2. (A) Lung metastases were established in BALB/c mice via tail vein injection of 5 × 105 CT26‐GCCTM cells on day 0. Mice were immunized with control or GCCECD AV on day 3 and boosted with control or GCCECD VV on day 10. Plasmids expressing mouse GM‐CSF (pGM‐CSF) or IL‐2 (plL‐2) or PBS (control) were mixed with the viruses and co‐injected with both the prime and boost immunizations. Lung metastases were then enumerated on day 15. (B) Immunization with GCCECD alone was suboptimal with respect to tumor burden following nodule enumeration. However, inclusion of 10 μg of plasmid DNA expressing mouse GM‐CSF or IL‐2 with the viral immunizations significantly augmented vaccine efficacy (C and D, respectively). Data indicate means of N= 8–10 mice per group ± SD; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, two‐sided Student's t‐test.

Discussion

Identification of optimal target antigens is critical for the successful development of therapeutic immunization for adjuvant cancer therapy. 1 Novel approaches to antigen identification and vaccine paradigm synthesis should yield more effective cancer immunotherapeutics. 1 , 4 However, beyond inadequate target antigens, current immunotherapeutic approaches are hindered by limited insight into the components required for optimal immunization regimens and the perturbation of those regimens by tumorigenesis. 9 Several approaches to enhance vaccine efficacy or to unmask spontaneous antitumor responses in patients have been examined, including CTLA‐4 blockade; cytokine adjuvanation, such as GM‐CSF and IL‐2; T‐cell costimulation employing B7‐1, ICAM‐1, and LFA‐3; and Treg depletion, among others. 10

Here, we examined the adjuvanation of therapeutic GCC‐specific immunization by GM‐CSF and IL‐2 in a mouse model of metastatic colorectal cancer. Both cytokines increased the efficacy GCC‐specific immunization, reducing formation of metastases by 50%–75%. Going forward, it is anticipated that purified recombinant cytokines will provide greater increases in immune responses to target antigens than those obtained with plasmid DNA‐based expression systems in vivo. Future studies should combine these cytokines and incorporate strategies targeting immune activation pathways beyond those of GM‐CSF and IL‐2, such as regulatory T cell‐mediated suppression, tumor sensitization and T‐cell receptor activation to achieve maximal antitumor efficacy 10 Moreover, the safety of adjuvanated GCC‐based immunization should be examined to confirm that this immunization regimen does not breach immune compartments and induce intestinal autoimmunity.

Conclusion

While GCC‐targeted immunization offers efficacy superior to that of other antigens for colorectal cancer immunotherapy, 2 , 4 opportunity exists to maximize responses beyond that achieved with recombinant viral vector‐based immunization regimens. The results presented here identify the cytokines GM‐CSF and IL‐2 as effective adjuvants for GCC‐specific immunotherapy. They suggest that immunization regimens to prevent and treat metastatic colorectal cancer in animal models and patients will require incorporation of GM‐CSF and IL‐2 to maximize therapeutic responses to cancer mucosal antigens.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (CA75123, CA95026) and Targeted Diagnostic and Therapeutics Inc. (to S.A.W.) and a Measey Foundation Fellowship (to A.E.S.). S.A.W. is the Samuel M.V. Hamilton Endowed Professor.

References

- 1. Dalerba P, Maccalli C, Casati C, Castelli C, Parmiani G. Immunology and immunotherapy of colorectal cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003; 46: 33–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Snook A, Stafford B, Eisenlohr L, Rothstein J, Waldman S. Mucosally‐restricted antigens as novel immunological targets for anti‐tumor therapy. Biomarkers in Med. 2007; 1: 187–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Snook AE, Eisenlohr LC, Rothstein JL, Waldman SA. Cancer mucosa antigens as a novel immunotherapeutic class of tumor‐associated antigen. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007; 82: 734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Snook AE, Stafford BJ, Li P, Tan G, Huang L, Birbe R, Schulz S, Schnell MJ, Thakur M, Rothstein JL, Eisenlohr LC, Waldman SA. Guanylyl cyclase C‐induced immunotherapeutic responses opposing tumor metastases without autoimmunity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008; 100: 950–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McLaughlin JP, Schlom J, Kantor JA, Greiner JW. Improved immunotherapy of a recombinant carcinoembryonic antigen vaccinia vaccine when given in combination with interleukin‐2. Cancer Res. 1996;56: 2361–2367 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marshall JL, Hoyer RJ, Toomey MA, Faraguna K, Chang P, Richmond E, Pedicano JE, Gehan E, Peck RA, Arlen P, Tsang KY, Schlom J. Phase I study in advanced cancer patients of a diversified prime‐and‐boost vaccination protocol using recombinant vaccinia virus and recombinant nonreplicating avipox virus to elicit anti‐carcinoembryonic antigen immune responses. J Clin Oncol. 2000; 18: 3964–3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aarts WM, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Vector‐based vaccine/cytokine combination therapy to enhance induction of immune responses to a self‐antigen and antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 2002; 62: 5770–5777 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ko HJ, Kim YJ, Kim YS, Chang WS, Ko SY, Chang SY, Sakaguchi S, Kang CY. A combination of chemoimmunotherapies can efficiently break self‐tolerance and induce antitumor immunity in a tolerogenic murine tumor model. Cancer Res. 2007; 67: 7477–7486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rabinovich GA, Gabrilovich D, Sotomayor EM. Immunosuppressive strategies that are mediated by tumor cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007; 25: 267–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Palena C, Abrams SI, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Cancer vaccines: preclinical studies and novel strategies. Adv Cancer Res. 2006; 95: 115–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]