Abstract

Motivation: A basic question in protein science is to which extent mutations affect protein thermostability. This knowledge would be particularly relevant for engineering thermostable enzymes. In several experimental approaches, this issue has been serendipitously addressed. It would be therefore convenient providing a computational method that predicts when a given protein mutant is more thermostable than its corresponding wild-type.

Results: We present a new method based on support vector machines that is able to predict whether a set of mutations (including insertion and deletions) can enhance the thermostability of a given protein sequence. When trained and tested on a redundancy-reduced dataset, our predictor achieves 88% accuracy and a correlation coefficient equal to 0.75. Our predictor also correctly classifies 12 out of 14 experimentally characterized protein mutants with enhanced thermostability. Finally, it correctly detects all the 11 mutated proteins whose increase in stability temperature is >10°C.

Availability: The dataset and the list of protein clusters adopted for the SVM cross-validation are available at the web site http://lipid.biocomp.unibo.it/~ludovica/thermo-meso-MUT.

Contact: casadio@alma.unibo.it

1 INTRODUCTION

Predicting the thermostability of a biomolecule, given its sequence, is one of the big challenges of protein biochemistry and biotechnology (Bommarius et al., 2006; Razvi and Scholtz, 2006). In this respect, it is of great relevance developing a tool that can score protein sequences in order to screen thermostable mutants among a plethora of alternative mutated sequences (Hoppe and Shomburg, 2005). The accumulation of genomic data, comprising thermophilic organisms, allows for a comprehensive investigation of nucleotidic and amino acidic sequences with the aim of discovering universal determinants of thermophilic life. Many studies have attempted to correlate thermostability to both the genome and proteome compositions. At the DNA level, differences in the codon usage between thermophilic and mesophilic organisms have been described (Lobry and Chessel, 2003; Lobry and Necsulea, 2006; Lynn et al., 2002; Singer and Hickey, 2002; Takami et al., 2004). Recently, a codon frequency index could highlight robust determinants of thermostability capable of discriminating thermophilic from mesophilic genomes (Montanucci et al., 2007). When residue composition in proteomes and/or protein sequences and structures were analyzed, the increased frequency in charged residues and ion pairs was recognized as the most remarkable feature of thermostable proteins (Farias and Bonato, 2003; Kreil and Ouzounis, 2001; Shure and Claverie, 2003; Szilágyi and Závodsky, 2000; Zhang and Fang, 2006a). However, many other compositional features may influence protein thermostability (see Zhou et al., 2008, for a recent review, and references therein) and molecular determinants of thermal resistance at the protein level still remain elusive. Recently, the fraction of a set of protein residues (I, V, Y, W, R, E, L) in the proteome was correlated with the optimal growth temperature of the correspondent organism (Zeldovich et al., 2007).

In this article, we address the problem of screening mutations that affect protein thermostability and develop a novel method able to sort out thermostable protein variants at the sequence level.

As discussed above, several methods have been described for discriminating among thermophilic and mesophilic proteins. In the present work, our approach is different in that we aim at predicting whether a set of mutations (including deletions and insertions) can enhance the thermostability of a given protein. For this reason, and differently from previous implementations (Zhang and Fang, 2006b) we trained a SVM method on the compositional difference computed for 2328 pairs of mesophilic and thermophilic proteins that share high pairwise sequence identity (≥70%).

2 METHODS

2.1 Training dataset

Our training/testing dataset consists of 2328 pairs of protein sequences with the property that one member belongs to a thermophilic microbial organism and the other to a mesophilic one. Since we are interested in detecting small differences in composition, we considered only protein pairs sharing a sequence identity ≥70%. The corresponding pairwise alignment coverage is >80% for the vast majority of the cases (∼90%).

This dataset was derived from an extensive all-against-all BLAST search among the proteomes of 112 prokaryotes (12 of which are thermophilic) belonging to different genera, comprising Archaea and Bacteria. From the outputs of the BLAST runs only aligned sequence pairs comprising a mesophilic and a thermophilic protein were selected. Only protein pairs sharing at least 70% of sequence identity were retained. The final number of pairs is 2328, including 378 thermophilic and 1015 mesophilic proteins.

2.2 Definition of training and testing sets

One of the major problems in developing and evaluating predictors is avoiding the similarity between training and testing sets; usually random splitting is not a correct procedure (Appendix 1). For this reason we clustered proteins using a very conservative method. We considered protein sequences as graph nodes. Two nodes are linked by an edge if the local identity between the two corresponding sequences is >30%. The graph is then a forest and the connected components define our clusters. In this way, a cluster may contain proteins that by themselves do not share a sequence identity >30% but that are connected through a path of similar proteins. This procedure grouped the 1393 protein sequences of the dataset into 184 non-overlapping clusters, containing the 2328 pairs of interest. Also, each cluster contains proteins that are <30% identical to those of all the other clusters.

Although apparently too restrictive, this clustering procedure is safer for defining training and testing sets. We then used a ‘leave-one-cluster-out’ training procedure by predicting all the proteins of one cluster with the model trained on the remainder of the data set.

In order to prove the necessity for a similarity-clustered validation scheme, we generated also a random splitting of the data set and we trained and tested the method accordingly. From Table A1 of Appendix 1, it is evident that when random splitting is adopted, the SVM performance increases due to the higher level of homology between the training and testing sequences.

Table 1.

Experimental dataset description

| Protein name | Length | Temp. (○C) | Mutant name | Temp. (○C) | Mutated residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shble | 124 | Tm: 67.4 | HTS | Tm: 85.1 | G18E,D32V,L63Q,G98V |

| UVF | Tm: 99 | 39 mutations | |||

| Dmeh | 54 | Tm: 49 | |||

| UMC | Tm: 99 | 40 mutations | |||

| β-GUS | 603 | 45 | TR3337 | 65 | Q493R,T509A,M532T,N550S,G559S,N566S |

| mt1 | Tm: 69.7 | A46K,S48R | |||

| BsCSP | 67 | Tm: 53.8 | |||

| mt2 | Tm: 83.7 | M1R,E3K,K65I | |||

| EcHPH | 341 | 51 | hph5 | 67 | D20G,A118V,S225P,Q226L,T246A |

| 12x | 59.7 | V71I,E130K,Q132R,Q137R,I150F,Q215L,R275Q,L276Q,I313L,V315A,A319E,A325V | |||

| PTDH | 355 | 39 | |||

| opt14 | 64.4 | V71I,E130K,Q132K,Q137H,I150F,Q215L,R275L,L276C,I313L,V315A,A319E,A325V,A146S,F198M | |||

| CbADH | 452 | Tm: 65.5 | Q100P | ΔTm: +11.5 | Q100P |

| FAOX | 372 | 37 | FAOX_TE | 45 | T60A,A188G,M244L,N257S,L261M |

| PDAO | 347 | 45 | F42C | 55 | F42C |

| mt18 | ΔTm: +7, | A58E,P65S,Q191R,T271R | |||

| PhyA | 467 | 55 | |||

| mt24 | ΔTm: >+7 | A58E,P65S,Q191R,T271R,E228K,S149P,F131L |

In the first two columns the wild-type protein name and the protein length are reported. In the fourth column, the name of the mutant is reported. Columns 3 and 5 report optimal functional temperatures of the wild-type and the mutated sequence, respectively; Tm when present refers to the melting temperature; column 6 reports the mutated residues. In the case of Dmeh, the two mutants have 39 and 40 mutated residues, respectively (Shah et al., 2007). The considered proteins are: Shble: bleomycin-binding protein from the mesophilic bacterium Streptoalloteichus hindustanus (Brouns et al., 2005); Dmeh: Drosophila melanogaster engrailed homeodomain (Shah et al., 2007); β-GUS: β-glucuronidase (Xiong et al., 2007); BsCSP: cold shock proteins from Bacillus subtilis (Max et al., 2007); EcHPH: Escherichia coli hygromycin B phosphotransferase (Nakamura et al., 2005); PTDH: phosphite dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas stutzeri (Johannes et al., 2005; McLachlan et al., 2007) CbADH: Clostridium beijerinckii alcohol dehydrogenase (Goihberg et al., 2007); FAOX: fructosyl-amino acid oxidase from Corynebacterium sp. (Sakaue and Kajiyama, 2003); pDAO: porcine kidney D-amino acid oxidase (Bakke et al., 2006); PhyA: 3-phytase A from Aspergillus niger (Zhang and Lei, 2007).

2.3 A test set of experimentally investigated protein mutations

To validate our method with real-world applications, we collected an experimental dataset derived from the literature. This set consists of mesophilic proteins that have been experimentally mutated resulting in proteins that show an increased optimal functional temperature (or melting temperature Tm). This experimental set consists of 14 mutants derived from 10 different wild-type proteins (for details, see Table 1). Among the data reported in the literature we did not consider examples that: (i) do not specify the optimal (nor the melting) temperature increment; (ii) describe proteins thermally stabilized by means of chemical post-translational modifications instead of residue mutations (such as Annaluru et al., 2007; Siddiqui and Cavicchioli, 2005; Li et al., 2007; Minagawa et al., 2007; Ruller et al., 2007; Salazar et al., 2003; Stephens et al., 2007).

2.4 Support vector machines

Two support vector machines (SVMs) were trained with linear kernel functions, using the libsvm package (http://www.csie.ntu.edu.tw/~cjlin/libsvm). They differ in the input encoding adopted. The first SVM (L20) takes as input 20-valued vectors containing the difference of the residue composition in each pair of the dataset. The second SVM (L400) takes as input 400-valued vectors containing the difference of the dipeptide composition in each pair of the dataset.

For each encoding type (L20 and L400) and for each protein pair in the data set, two different input vector sets were derived: a vector set encoding the composition (residue or dipeptide) difference between the thermophilic sequence and the mesophilic one (positive set), and a vector set encoding the composition (residue or dipeptide) difference between the mesophilic sequence and the thermophilic one (negative set). By this a total of 4656 input vectors were defined. This encoding procedure ensures balancing of the positive and negative examples.

For each trained SVM we evaluated the performance using different values for the C parameter in the range of 0.1–100 000 (see the libsvm package). The linear kernel SVM showed a high degree of robustness and the accuracy was not significantly affected by a specific value of the C parameter. The results presented below are computed using values for the C parameter equal to 10 000 and 1000 for L20 and L400, respectively.

Finally, a combined SVM was derived by taking the average values of the probabilities given by L20 and L400.

2.5 Evaluating the predictor performances

The evaluation of the performance of the two-class classifiers was determined using the following statistical indexes. The two classes are indicated as positive (+: increased thermostability) and negative (−: decreased thermostability). The overall accuracy of the classifier is defined as:

| (1) |

where P is the total number of correct classifications and N is the total number of examples. The correlation coefficient C is defined as:

| (2) |

where p and n are the number of correctly classified examples of the positive and negative class, respectively; o is the number of examples of the negative class predicted as belonging to the positive one, and u is the number of examples of the positive class predicted as belonging to the negative one. The normalization factor D is given by:

| (3) |

The probability of correct prediction, or specificity, for the two classes is defined as:

| (4) |

| (5) |

The coverage, or sensitivity, for the two classes is defined as:

| (6) |

| (7) |

We define the reliability score for each SVM as:

| (8) |

where P(i) is the probability assigned by a SVM for the i-th input vector. It ranges from 0 to 9.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Scoring the SVM predictors

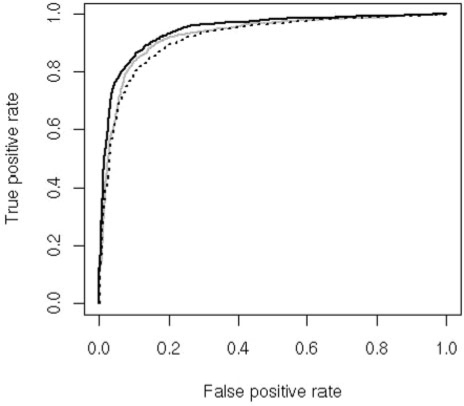

The scoring indexes of the different methods were evaluated with the ‘leave-one-cluster-out’ procedure and are reported in Table 2. It is evident that both SVM L20 and SVM L400 perform quite well and that accuracies are almost indistinguishable in spite of the fact that L400 has far more detailed input to work with. This indicates that the most relevant information is contained in the composition difference of two highly homologous thermophilic and mesophilic proteins (≥70%) and that more detailed information of the difference in dipeptide composition does not significantly increase the performance. However, the two predictors are able to extract slightly different features as indicated by the finding that the combined SVM predictor outperforms the single L20 and L400, reaching an accuracy of 88% and a correlation coefficient of 0.75. The scoring improvement of the combination of two different methods is not unexpected since it is theoretically founded when they capture different features (Sollich and Krogh, 1996). The same picture holds when the ROC curves reported in Figure 1 are considered and where the true positive rate [Sensitivity(+)] is plotted versus the false positive rate [1-Sensitivity(−)].

Table 2.

Performances of the two SVMs and the Combined SVM method

| Method | Accuracy (%) | Correlation | Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity(%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | + | − | |||

| L20 | 86 | 0.73 | 87 | 86 | 86 | 87 |

| L400 | 85 | 0.70 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 85 |

| Combined | 88 | 0.75 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 |

The performances are evaluated using the leave-one-cluster-out procedure on the training dataset. The symbol + and − indicate the direction of increased an decreased thermostability, respectively.

Fig. 1.

ROC curve of the three predictors. Solid gray line: L20 SVM predictor; dotted black line: L400 SVM predictor; solid black line: combined predictor.

We should also consider that the predictions are very well balanced, reaching the same sensitivity and specificity values for the two classes.

3.2 Robustness of the performance

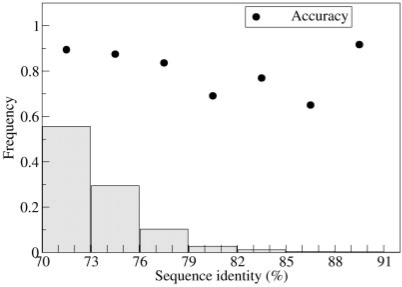

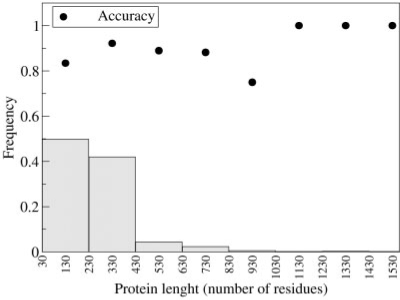

The SVM performance can be affected by the encoding procedure given the different protein identity values (70–92%) and different protein lengths (35–1512 residues) in the dataset of protein pairs. In Figures 2 and 3, we show the accuracy of the combined SVM as a function of protein sequence identity (Fig. 2) and length (Fig. 3) of the pairs, respectively. It is evident that the performance is quite independent of both the identity value and protein length of the pair.

Fig. 2.

The accuracy of the combined SVM method is plotted with respect to the sequence identity, grouped into bins of identity, in the pair. Bars indicate the frequency of pairs in the training set with a given identity value.

Fig. 3.

The accuracy of the combined SVM method is plotted with respect to the protein length in the pair. For each pair the maximum protein length was chosen. Bars indicate the frequency of pairs in the training set with a given protein length.

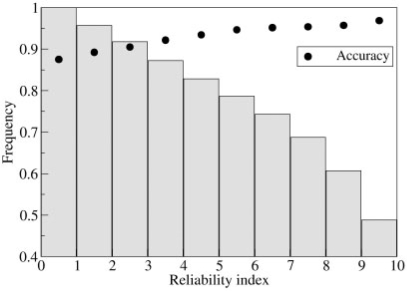

An important issue when implementing and testing a predictive method is the possibility to compute a reliability score of the prediction. This helps in scoring the performance of the method; furthermore, it can also be used to sort out the set of mutations that are more likely to increase protein thermostability in a rational computer-aided protein design.

In this respect, we tested the behavior of our method by computing its accuracy as function of the reliability measure [see Section 2, Equation (8)]. From the data shown in Figure 4 it can be concluded that for about half of the dataset the method accuracy is >95%.

Fig. 4.

The accuracy of the combined SVM method is plotted with respect to the reliability index. Bars represent the fraction of the database with a given value of reliability index.

3.3 A blind test on experimentally validated data

In order to validate our methods on a real-world application we further tested them on an experimentally verified dataset.

For sake of precision we checked if the sequences of the experimental set were included in the training set. For this reason, the 10 wild-type sequences of the experimental set were aligned with the BLAST program against all the sequences of the training set. In nine cases, BLAST gave no hits. Only the Bacillus subtilis CSP (BsCSP) retrieved BLAST hits with nine (seven of which mesophilic and two thermophilic) proteins in the training set. Since these proteins were all included in a unique cluster, the predictions for the two BsCSP mutants were carried out using the SVM model trained without the cluster containing all the BsCSP ‘homologues’.

Protein pairs included in the experimental sets are endowed with an average number of mutations that is very small with respect to the pairs included in the training set. Despite this fact, the results reported in Table 3 show that the performances of our methods on the experimental set are similar to those obtained on the training/testing dataset. It is also worth noticing that the combined SVM method correctly predicts all the 11 experimental mutants whose thermostability is endowed with a ΔT value >10○C (Table 3).

Table 3.

SVM performances for the experimental dataset

| Protein | Mutant | ΔT○C | N○muts | L20 | L400 | Combined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dmeh | UVF | 50 | 39 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dmeh | UMC | 50 | 40 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| BsCSP | mt2 | 29.9 | 3 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| PTDH | opt14 | 25.4 | 14 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| PTDH | 12x | 20.7 | 12 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| β-GUS | TR3337 | 20 | 6 | No | Yes | Yes |

| Shble | HTS | 17.7 | 4 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| EcHPH | hph5 | 16 | 5 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| BsCSP | mt1 | 15.9 | 2 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CbADH | Q100P | 11.5 | 1 | Yes | No | Yes |

| pDAO | F42C | 10 | 1 | No | Yes | Yes |

| FAOX | TE | 8 | 5 | Yes | No | No |

| PhyA | mt24 | >7 | 4 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| PhyA | mt18 | 7 | 7 | Yes | No | No |

| Accuracy for all the mutations (%) | 12/14 (86) | 11/14 (79) | 12/14 (86) | |||

| Accuracy for the subset with ΔT≥10○C (%) | 9/11 (82) | 10/11 (91) | 11/11 (100) | |||

Protein is the short name of the wild-type protein (refer to Table 1 for details); Mutant is the name of the mutated sequence; ΔT is the experimentally measured increase in the optimal (or melting) temperature; N.muts is the number of mutations. The correct (yes) or incorrect (no) predictions of the three methods are reported in the last three columns.

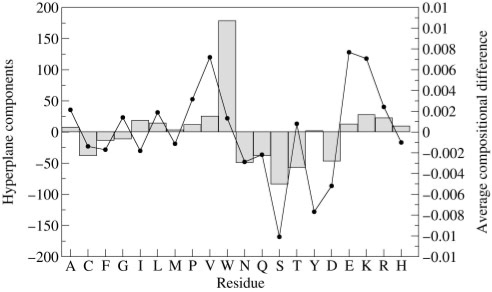

3.4 Analysis of the dominant SVM parameters

In order to get a better insight into the determinants of protein thermostability, we analyzed the support vectors selected by the SVMs during the training phase. In particular, since our kernel is linear, we easily obtained the hyper-plane vector W used by SVM for classification (Burges, 1998). The components of the vector normal to the discriminative hyper-plane can be computed as

| (9) |

where j runs from 1 to 20 and i runs over all the SVM support vectors; the αi are the positive and negative Lagrange multipliers and the Xi are the support vectors, respectively. In practice, given our choice of input vectors, the positive components of W imply a thermophilic propensity while the negative ones indicate a mesophilic character. The 20 components (one for each residue) of the W hyper-plane vector are plotted in Figure 5. These components can be contrasted with the average residue composition difference among thermophilic and mesophilic protein pairs as computed on the whole dataset (Figure 5, line and dots). It can be noticed that although the majority of the residues have the same sign in the two types of plots, the relevance of the single components is different. The SVM selection of the best hyper-plane induces a different and weighted choice of the components with respect to a simple statistical classifier (as highlighted in Figure 5). In particular, we can observe that residues that have been previously identified as robust determinants of thermostability (Montanucci et al., 2007, and references therein) are also highlighted by the SVM method. These are: (i) the increased abundance of glutamic acid (E) and lysine (K) and (ii) the decreased abundance of glutamine (Q) in thermostable chains. Besides glutamic acid (E) and lysine (K), the combined SVM classifier also highlights other residues as peculiar of a thermophilic character : alanine (A), isoleucine (I), leucine (L), methionine (M), proline (P), valine (V), tryptophan (W), tyrosine (Y), arginine (R) and histidine (H). In turn, the remaining residues (C, F, G, N, Q, S, T, D) are highlighted as indicative of a mesophilic character. It should be stressed, however, that none of these components alone is statistically significant to infer thermostability versus mesophilicity. Indeed, the distribution of the SVM components of the hyperplane vector is different from that of the simple average composition difference between thermophilic and mesophilic sequences in the data set (Figure 5, line and dots). The most unexpectedly relevant component highlighted by SVM is the tryptophan difference. The relative low abundance of tryptophan in protein sequences may have hampered this finding by previously adopted statistical classifiers. However, this feature is in agreement with more recent data indicating that a fraction of a set of protein residues (I, V, Y, W, R, E, L), including tryptophan, in the proteome is correlated with the optimal growth temperature of the correspondent organism (Zeldovich et al., 2007).

Fig. 5.

The values of the components of the hyperplane vector of SVM L20 are plotted as bars. The average compositional differences obtained by averaging all the training examples are plotted as dots connected by a line.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Several papers addressed so far the problem of characterizing determinants of thermostability. This is possible at the genome and at the proteome level, provided that determinants are statistically robust enough (Montanucci et al., 2007; Zeldovich et al., 2007, references therein). Other works have also attempted to discriminate whether a given sequence might belong to a thermophilic or a mesophilic organism (Zhou et al., 2008, for a recent review, and references therein). To perform this task, the information derived from entire genomes, proteomes or sets of thermophilic and mesophilic sequences was exploited. The problem was also tackled by means of SVM and others machine learning approaches (Zhang and Fang, 2006b).

In this article, we address a different issue since we try to derive automatic rules to predict when a set of mutations (including deletions and insertions) can enhance protein thermostability and this is novel. For this reason, a direct comparison with previous works is not possible, given the different inputs and goals. To our purpose, we explicitly sorted out the subset of protein sequences among thermophilic and mesophilic organisms that share a high degree of similarity and this was adopted for training/testing with a similarity-clustered procedure.

A careful analysis of the support vectors of our method highlights that residues contributing the most to protein thermostability in the protein set are the same derived by previous approaches on different protein sets, corroborating our observations.

Finally, our methods are tested on experimentally determined and never-seen-before protein mutants with enhanced thermostability. The results indicate that our best combined SVM predictor correctly classifies 12 mutated proteins out of 14. Furthermore, it correctly detects all the 11 mutated proteins that are endowed by an increase of the melting/optimal functional temperature, as experimentally characterized, of >10○C (Table 3).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding: R.C. acknowledges the receipt of the following grants: FIRB 2003 LIBI–International Laboratory of Bioinformatics and the support to the Bologna node of the Biosapiens Network of Excellence project within the European Union's VI Framework Programme (contract number LSGH-CT-2003-503265).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

APPENDIX 1

A.1 Results on a random splitting of training and testing sets

A three-fold cross validation was carried out using random splitting of the 4656 examples in the training set. The examples in the dataset were randomly split into three sets. The training/testing splitting was therefore carried out regardless of the redundancy and sequence similarity among the considered sequences. At each cross-validation run, 3104 examples were used for training and 1552 for the test. The performances of the obtained classifier are shown in Table A1. When these results are compared to those shown in Table 1, it is evident that SVM scoring is enhanced when redundancy among the training and testing set is retained.

Table A1.

Performances obtained with random splitting of the cross-validation sets

| Method | Accuracy (%) | Correlation | Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | + | − | |||

| L20 | 93 | 0.86 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 |

| L400 | 97 | 0.94 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 |

L20 is the SVM trained with the residue composition. L400 is trained with the difference in dipeptide composition of the sequences. Symbols + and − indicate increased and decreased thermostability classes, respectively.

REFERENCES

- Annaluru N, et al. Thermostabilization of Pichia stipitis xylitol dehydrogenase by mutation of structural zinc-binding loop. J. Biotechnol. 2007;129:717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakke M, et al. Thermostabilization of porcine kidney D-amino acid oxidase by a single amino acid substitution. Biotechnol. Bioeng., 2006;93:1023–1027. doi: 10.1002/bit.20754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommarius AS, et al. High-throughput screening for enhanced protein stability. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2006;17:606–610. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouns SJ, et al. Engineering a selectable marker for hyperthermophiles. J. Biol. Chem., 2005;280:11422–11431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burges CJC. A Tutorial on Support Vector Machines for Pattern Recognition. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Farias ST, Bonato MCM. Preferred amino acids and thermostability. Genet. Mol. Res. 2003;2:383–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goihberg E, et al. A single proline substitution is critical for the thermostabilization ofClostridium beijerinckiialcohol dehydrogenase. Proteins. 2007;66:196–204. doi: 10.1002/prot.21170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe C, Shomburg D. Prediction of protein thermostability with direction and distance-dependent knowledge-based potential. Prot. Sci. 2005;14:2682–2692. doi: 10.1110/ps.04940705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes TW, et al. Directed evolution of a thermostable phosphite dehydrogenase for NAD(P)H regeneration. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 2005;71:5728–5734. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5728-5734.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreil DP, Ouzounis CA. Identification of thermophilic species by the amino acid composition deduced from their genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1608–1615. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.7.1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, et al. A diverse family of thermostable cytochrome P450s created by recombination of stabilizing fragments. Nat. Biothecnol. 2007;25:1051–1016. doi: 10.1038/nbt1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobry JR, Chessel D. Internal correspondence analysis of codon and amino-acid usage in thermophilic bacteria. J. Appl. Genet. 2003;44:235–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobry JR, Necsulea A. Synonymous codon usage and its potential link with optimal growth temperature in prokaryotes. Gene. 2006;385:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn DJ, et al. Synonymous codon usage is subjected to selection in thermophilic bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4272–4277. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Max KE, et al. Optimized variants of the cold shock protein from in vitro selection: structural basis of their high thermostability. J. Mol. Biol., 2007;369:1087–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan MJ, et al. Further improvement of phosphite dehydrogenase thermostability by saturation mutagenesis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2007;99:268–274. doi: 10.1002/bit.21546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minagawa H, et al. Improving the thermal stability of lactate oxidase by directed evolution. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007;64:77–81. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6409-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanucci L, et al. Robust determinants of thermostability highlighted by a codon frequency index capable of discriminating thermophilic from mesophilic genomes. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:2502–2508. doi: 10.1021/pr060670p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A, et al. In vivo directed evolution for thermostabilization ofEscherichia colihygromycin B phosphotransferase and the use of the gene as a selection marker in the host-vector system of Thermus thermophilus. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2005;100:158–163. doi: 10.1263/jbb.100.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razvi A, Scholtz JM. Lessons in stability from thermophilic proteins. Prot. Sci. 2006;15:1569–1578. doi: 10.1110/ps.062130306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruller R, et al. Thermostable variants of the recombinant xylanase a from Bacillus subtilis produced by directed evolution show reduced heat capacity. Proteins. 2007;70:1280–1293. doi: 10.1002/prot.21617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaue R, Kajiyama N. Thermostabilization of bacterial fructosyl-amino acid oxidase by directed evolution. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:139–145. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.1.139-145.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar O, et al. Thermostabilization of a cytochrome P450 peroxygenase. Chembiochem., 2003;4:891–893. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah PS, et al. Full-sequence computational design and solution structure of a thermostable protein variant. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shure K, Claverie JM. Genomic correlates of hypertermostability: an update. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:17198–17202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui KS, Cavicchioli R. Improved thermal stability and activity in the cold-adapted lipase B fromCandida antarcticafollowing chemical modification with oxidized polysaccharides. Extremophiles. 2005;9:471–476. doi: 10.1007/s00792-005-0464-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer,G.A.C. and Hickey DA. Thermophilic prokaryotes have characteristic patterns of codon usage, amino acid composition and nucleotide content. Gene. 2002;317:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00660-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollich P, Krogh A. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 8. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1996. Learning with ensembles: how overfitting can be useful; pp. 190–196. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens DE, et al. Directed evolution of the thermostable xylanase from Thermomyces lanuginosus. J. Biotechnol. 2007;127:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilágyi A, Závodsky P. Structural differences between mesophilic, moderately thermophilic and extremely thermophilic protein subunits:results of a comprehensive survey. Structure, 2000;8:493–503. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takami H, et al. Thermoadaptation trait revealed by the genome sequence of thermophilic Geobacillus kaustophilus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:6292–6303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong AS, et al. Concurrent mutations in six amino acids in β-glucuronidase improve its thermostability. Prot. Eng. Design Select., 2007;20:319–325. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzm023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeldovich KB, et al. Protein and DNA sequence determinants of thermophilic adaptation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Fang B. Study on the discrimination of thermophilic and mesophilic proteins based on dipeptide composition. Chinese J. Biothechnol., 2006b;22:293–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Fang B. Support vector machine for discrimination of thermophilic and mesophilic proteins based on amino acid composition. Prot. Pept. Lett., 2006b;13:965–970. doi: 10.2174/092986606778777560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Lei XG. Cumulative improvements of thermostability and pH-activity profile ofAspergillus nigerPhyA phytase by site-directed mutagenesis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007;77:1033–1040. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou XX, et al. Differences in amino acids composition and coupling patterns between mesophilic and thermophilic proteins. Amino Acids, 2008;34:25–33. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0589-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]