Abstract

Motivation: In recent years stable isotopic labeling has become a standard approach for quantitative proteomic analyses. Among the many available isotopic labeling strategies, metabolic labeling is attractive for the excellent internal control it provides. However, analysis of data from metabolic labeling experiments can be complicated because the spacing between labeled and unlabeled forms of each peptide depends on its sequence, and is thus variable from analyte to analyte. As a result, one generally needs to know the sequence of a peptide to identify its matching isotopic distributions in an automated fashion. In some experimental situations it would be necessary or desirable to match pairs of labeled and unlabeled peaks from peptides of unknown sequence. This article addresses this largely overlooked problem in the analysis of quantitative mass spectrometry data by presenting an algorithm that not only identifies isotopic distributions within a mass spectrum, but also annotates matches between natural abundance light isotopic distributions and their metabolically labeled counterparts. This algorithm is designed in two stages: first we annotate the isotopic peaks using a modified version of the IDM algorithm described last year; then we use a probabilistic classifier that is supplemented by dynamic programming to find the metabolically labeled matched isotopic pairs. Such a method is needed for high-throughput quantitative proteomic metabolomic experiments measured via mass spectrometry.

Results: The primary result of this article is that the dynamic programming approach performs well given perfect isotopic distribution annotations. Our algorithm achieves a true positive rate of 99% and a false positive rate of 1% using perfect isotopic distribution annotations. When the isotopic distributions are annotated given ‘expert’ selected peaks, the same algorithm gets a true positive rate of 77% and a false positive rate of 1%. Finally, when annotating using machine selected peaks, which may contain noise, the dynamic programming algorithm gives a true positive rate of 36% and a false positive rate of 1%. It is important to mention that these rates arise from the requirement of exact annotations of both the light and heavy isotopic distributions. In our evaluations, a match is considered ‘entirely incorrect’ if it is missing even one peak or containing an extraneous peak. If we only require that the ‘monoisotopic’ peaks exist within the two matched distributions, our algorithm obtains a positive rate of 45% and a false positive rate of 1% on the ‘machine’ selected data. Changes to the algorithm's scoring function and training example generation improves our ‘monoisotopic’ peak score true positive rate to 65% while obtaining a false positive rate of 2%. All results were obtained within 10-fold cross-validation of 41 mass spectra with a mass-to-charge range of 800–4000m/z. There are a total of 713 isotopic distributions and 255 matched isotopic pairs that are hand-annotated for this study.

Availability: Programs are available via http://www.cs.wisc.edu/~mcilwain/IDM/

Contact:mcilwain@cs.wisc.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years a variety of technological advances have fueled the development of proteomics as an important component of systems biology. Proteomics can be defined as the high-throughput study of global patterns of protein expression and post-translational modifications in biological systems. Fundamentally, proteomics experiments involve two distinct experimental goals: identification of peptides and proteins and comparison of their abundances across multiple samples. In recent years the central technology for this work has been liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS), which can be used to address both of these issues. Identification of peptides via tandem mass spectrometry has become routine thanks to a variety of algorithms that identify peptide amino acid sequences from mass spectrometry data (Sadygov et al., 2004).

Considerable effort has also been devoted to the development of automated experimental strategies to extract quantitative information from mass spectra in high-throughput proteomics and metabolomics experiments. While a variety of approaches have been developed, use of isotopic labeling techniques has been especially widespread in the proteomics field (Domon and Aebersold, 2006). Though the nature of the isotopic label differs, all isotopic labeling approaches are intended to compare abundances of particular analytes within pairs or sets of samples. During an experiment these samples are each labeled, one with a ‘light’ isotope and the other a ‘heavy’ isotope. After mixing these differentially labeled samples, relative quantitative information is obtained by comparing the intensity ratios between the ‘heavy’ and ‘light’ isotopic peaks of the compound.

A wide variety of isotopic labeling strategies have been developed that differ in the nature of the isotopic label used as well as the way in which that label is introduced into each sample. Examples include iTRAQ and ICAT, as well as metabolic labeling (Babnigg and Giometti, 2003; Beynon and Pratt, 2005; Choe et al., 2005; DeSouza et al., 2005; Flory et al., 2002; Guina et al., 2003; Gygi et al., 1999; Han et al., 2001; Hardt et al., 2005; Krijsveld et al., 2003; Ranish et al., 2003; Ross et al., 2004; Shiio et al., 2002; Shiio et al., 2003; von Haller et al., 2003a,b). The iTRAQ and ICAT strategies involve isotopically labeled reagents that are introduced chemically onto each molecule during sample preparation. Metabolic labeling, however, involves replacing existing atoms with a heavy isotope in an organism's diet (e.g. replace all 14N's with 15N's) through normal growth and development.

For those organisms that can be efficiently grown on isotopically enriched food or media, metabolic labeling can be especially useful because it allows samples to be combined for all stages in sample preparation, from tissue extraction through mass spectrometric analysis. Thus it provides internal control for all steps in the experiment. However, analysis of metabolic labeling data can be complicated compared to other isotopic labeling strategies. Unlike techniques such as ICAT that typically produce a fixed mass difference between labeled and unlabeled forms of each peptide, the mass difference between labeled and unlabeled forms of each peptide depends on the chemical formula of each particular peptide and thus varies considerably from analyte to analyte. Thus, without knowing the sequence of a peptide, it can be difficult to match its light and heavy distributions. Ultimately, quantification of unknown peptides in an automated fashion via metabolic labeling can be problematic.

When applying metabolic labeling in practice, researchers have dealt with the issue of variable spacing by first identifying peptides based on their MS/MS sequencing patterns and later quantifying only those peptides that were confidently identified. However, if light and heavy pairs could be matched for unknown peptides, this approach could be useful in multiple ways. First, if light and heavy pairs were matched prior to MS/MS database searching, then their spacing would provide an additional sequence constraint (i.e. number of nitrogens) that could be used to improve the quality of the resulting peptide identifications (Hegeman et al., 2007; Nelson et al., 2007; Pratt et al., 2002; Snijders et al., 2005; Zhong et al., 2004). Additionally, the ability to quantify unknown peptides via metabolic labeling would be especially useful for instruments such as Time of Flight (TOF)–TOF mass spectrometers that can decouple MS and MS/MS data collection. Using these instruments, MS data could be collected alone and analyzed to identify peptide pairs that show significant differences in abundance. These particular pairs could then be targeted for subsequent MS/MS sequencing, allowing specific characterization of peptides whose abundance differs among the two samples. For these reasons we are most interested in developing an algorithm that can automatically identify pairs of heavy and light distributions within metabolic labeling datasets.

We describe a method that will take an isotopic map given from our previous algorithm (McIlwain et al., 2007) and annotate the light–heavy matched pairs. To accomplish this, we again use a dynamic programming approach based upon work from Craven et al. (2000) which predicts operons within a DNA sequence from the Escherichia coli K-12 genome. Their algorithm employs dynamic programming, building upon using a naïve Bayes model that predicts the probability of an operon given the data. Using expert-constructed peak lists from the spectra, we show that the dynamic programming map algorithm achieves a competitive true positive/false positive rate when compared to the classifier used to score matched isotopic distributions. We run our algorithm using peak lists annotated in three ways: (1) the expert supplies the correct isotopic annotations, (2) the expert supplies the correct unannotated peaks and (3) machine selected peaks. For the last two methods, we use our isotopic distribution annotation algorithm from last year to provide the isotopic distribution annotations.

Our algorithm takes as input a peak list and its isotopic distribution annotations. This allows us to try other isotopic annotation algorithms easily. The results suggest that improving or trying different isotope distribution annotation programs should improve our method's matching performance.

We show an algorithm that assumes that we only match an isotopic distribution to the previous distribution in the list, i.e. 1-step look-back. We then generalize our algorithm to perform n-step look-back and show that a 3-step look-back gives the best performance. Finally, we modify our algorithm's example generation and scoring function for the isotopic distribution and matched isotopic pairs to improve our results with the ‘machine’ selected peak case.

2 APPROACH

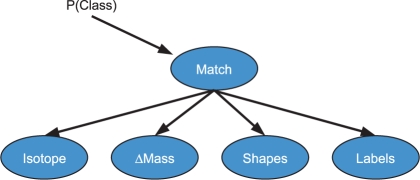

Using probabilities from features of distributions such as isotope probabilities, the mass-to-charge (m/z) or mass difference between the two matched isotopic distributions, and the shapes of the two distributions, we can construct a naïve Bayesian model, illustrated in Figure 1, to estimate the probability that two proposed distributions of peaks constitute a matched pair of isotopic distributions. By ‘a matched isotopic pair’ we mean both that (1) both distributions arise from the same molecular compound, but have a difference in their 14N/15N isotopic enrichment and (2) no other peaks from the same compound are in the spectrum. We can estimate the parameters (probabilities) of the naïve Bayes model using either the literature or training data, i.e. some annotated spectra. In our work, we choose to estimate the parameters from hand-annotated spectra.

Fig. 1.

Example naïve Bayes model for estimating isotopic match distribution probabilities.

Given a probability for each potential matched isotopic distribution pair, we would like to map all of the annotated isotopic distributions of a mass spectrum into their corresponding matched pairs. We take the score of any isotopic distribution to be the log (base 2) probability of the match to which it is mapped, and we take the score of a map to be the sum of the match scores. We also introduce a penalty term (γp) for not matching the isotope to a previous one.

We now describe in detail our 1-step look-back matching algorithm. In the dynamic programming approach, we use the distribution probabilities from the Bayes net to calculate G(i, j), where G(i, j) is the probability that the light isotopic distribution, i is matched to the heavy distribution j. M(j) denotes the optimal match map, or sequence of matched isotopic distributions up to distribution j. For successive values of j, we calculate the states for leaving the isotope j unmatched, or matching to the previous isotope. In order to make sure we do not overlap matches, we need to keep track of the state of the previous isotope. So now MXY(j)(X={P,A,N},Y={P,A}) has three possible states:

MAA(j)—both the current and previous isotopic distributions are available

MPA(j)—the current distribution is unmatched, but the previous is matched to its previous

MNP(j)—the current is matched to the previous isotopic distribution

So the substates are:

A—Unmatched or Available

N—Matched to next isotope

P—Matched to previous isotope

The overall score for M(j) is given by the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

For each j, we record the previous substate that the current substate came from. At the end of the run, we calculate the state with the best score as our ending state and now are able to recover the optimal match map based upon the recorded substates from the MXY(j)'s.

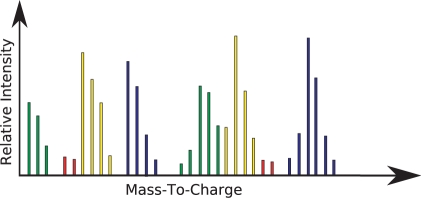

The run-time of the algorithm is linear in the number of isotopic distributions, n, in the spectrum. Unfortunately, there are cases where the matches can overlap such as in Figure 2. Cases such as these can be handled by modifying the algorithm for a 2-step or 3-step look-back algorithm. Actually, we are able to do an n-step look back generally by calculating the required substates and transition equations.

Fig. 2.

Example of annotated mass spectrum. The red color corresponds to noise peaks. The distributions of the same color are the light–heavy matched pair.

For each look-back step we need to keep track of an extra previous isotopic distribution. We also need to introduce extra substates that signify a match between the n-th step isotopes. For example a 2-step look back has five possible substates.

Q—Matched to previous–previous isotope

P—Matched to previous isotope

A—Unmatched or Available

N—Matched to next isotope

M—Matched to next–next isotope

The M for a 2-step is MXYZ, where

X is the state of the previous–previous isotope with possible substates are Q, P, A, N and M.

Y is the state of the previous isotopes with possible substates of Q, P, A and N.

Z is the state of the current isotope with possible substates of Q, P and N.

The valid substates are determined by enforcing these two rules: (1) an isotopic distribution cannot be matched to two different isotopic groups and (2) M and N are appropriately matched to Q and P, respectively. For a 2-step algorithm this gives 11 possible states for M: MAAA, MQAA, MPAA, MNPA, MQQA, MAQA, MQNP, MPNP, MANP, MMQQ and MMAQ.

Once the possible states are determined, we now generate the allowed transitions to from one state to another to derive the M equations. For 2-step, there are three possible options for each state, (1) leave unmatched, (2) match to previous isotope and (3) match to previous–previous isotope. For the initial MXYZ(0) states, we set a value of 0 for any state that has X, Y and Z unavailable for matching and −∞ for the rest. For the 2-step look back, the resulting equations are:

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

| (23) |

| (24) |

| (25) |

| (26) |

| (27) |

| (28) |

| (29) |

This process produces the n-step look-back dynamic programming algorithms. Unfortunately, the number of states and equations increase exponentially with the number of look-back steps (Table 1). Our results show, however, that the benefits of the look back are reduced beyond three steps. This is likely because the separation between pairs of matching distributions is limited due to restrictions on sizes and elemental compositions for tryptic peptides. Furthermore, though our data come from characterization of a complex Arabidopsis protein digest, all spectra were collected during an extended LC-MALDI separation that greatly reduced sample complexity in any single spectrum. At this level of separation, the likelihood of finding more than two identifiable isotopic distributions between a pair of heavy and light distributions in a single spectrum is small. The optimal number of look-back steps could vary, depending on the nature of the sample and the extent of fractionation prior to analysis.

Table 1.

Number of states and equations for number of look backs used in the dynamic programming algorithm

| Look back | States | Equations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 5 |

| 2 | 11 | 21 |

| 3 | 49 | 105 |

| 4 | 257 | 599 |

| 5 | 1539 | 3831 |

We now derive the time complexity and prove optimality of our algorithm starting with the following theorem.

THEOREM 1. —

Given a sequence of isotopic distributions, such that no more than k−1 distributions can intervene between any matching pair, the algorithm runs in time O(k!n) and returns an optimal (maximum scoring) map of the spectrum into matched pairs of distributions.

PROOF. —

We sketch the proof here, beginning with runtime. Match scores for all pairs of distributions within k-places of one another can be precomputed in time O(nk) and accessed in constant time through a hash table. The dynamic programming algorithm then proceeds by considering progressively longer prefixes of the sequence of isotopic distributions from 1 to n. Each time it adds a distribution, it computes a map and a score for every possible ‘k-place ending’, that is, every possible match status for the last k isotopic distributions in this prefix. There are fewer than (k−1)! such endings [to be precise, (k−1)(k−3)(k−5)]. When adding the next distribution, say m, each possible k-place ending can arise from at most k possible k-place endings for the map of the first m−1 distributions, via a unique extension, or unique choice of match partner for the mth distribution. Computing the score for any one of these extensions can be done in constant time, given the earlier precomputation of match scores. Therefore, adding a single distribution can be done in time O(k!), so the entire algorithm runs in time O(k!n).

For correctness (optimality), we actually prove the following stronger result: for each possible k-place ending of the map, the algorithm computes the optimal map having that k-place ending. The proof is by induction on the total number of isotopic distributions in the spectrum. For the base case, suppose the spectrum has at most k total isotopic distributions. The algorithm computes the score for every possible map of up to k-distributions and returns the maximum. For the inductive portion of the proof, consider a spectrum having m+1 isotopic distributions. For sake of contradiction, suppose that for some k-place ending there exists a map with a better score than the one returned by the algorithm. Because both maps end the same way, the better map must have a better prefix, that is, must begin with a better map for the first m−k distributions. But because that prefix is also consistent with the k-place ending of the map returned by the algorithm, by the inductive hypothesis we know this prefix was also available to the algorithm, so it would have used this same prefix. ▪

2.1 Naïve Bayes model

We use a naïve Bayes model to calculate the matched isotopic pair probabilities. The features utilized by the model encode data about isotopic probabilities, the number of labels affected, the shapes, and m/z differences between the monoisotopic peaks of the matched isotopic distributions. The remainder of this section describes these in more detail.

The naïve Bayes model assumes these features are independent of one another given the class (true isotopic pair or not an isotopic pair). Even when this assumption is violated, naïve Bayes models often work better in practice than more complicated Bayesian models because the conditional independence assumption means the model needs to estimate fewer parameters from the data, often resulting in better parameter estimates.

2.2 Isotopic distribution probabilities

We use the naïve Bayes classifier used previously (McIlwain et al., 2007) to generate features that assign a probability of an isotopic distribution to the light and heavy isotopic distributions. We also generate a feature that is the product of these two probabilities.

2.3 Number of labels

Using the monoisotopic masses between the matched pairs, we calculate the expected number of 15N labels using the formula:

| (30) |

Where the masslabel=1.0078 in our case. We create features that are the real value, the rounded integer value and the squared difference between the calculated integer and real value. We also generate features that are a ratio of these three original features over the estimated mass. We calculate the difference between the numbers of labels (nitrogens) determined from the previous equation versus that of the ‘averagine’ molecule of the light mass (Senko et al., 1995).

Because our dataset is a mixture of normal peptides and their 15N isotopic labeled pairs, identifying the monoisotopic masses is not as straightforward as it might initially seem. When peptides contain all atoms at their natural abundances, the monoisotopic peak corresponds to the peak resulting from only a single isotope from each atom. This occurs when each atom is present exclusively in its lowest mass isotope (1H, 12C, 16O, 14N and 32S), so the monoisotopic peak is that peak in each natural abundance envelope with the lowest m/z value. When an 15N-label is introduced, the situation is more complicated: 15N-labeled peptides do not contain a true monoisotopic peak because every peak in the distribution can result from different combinations of labeled isotopes. However, as nearly complete 15N enrichment is reached, the isotopic envelope of each labeled peptide assumes a similar shape to its natural abundance counterpart, but shifted by 1 Da for each heavy isotope in the peptide. For our purposes, we will consider the heavy monoisotopic peak to be the peak within the labeled distribution that results predominantly from 1H, 12C, 16O, 15N and 32S, by analogy with its natural abundance form. Using the m/z values of these monoisotopic peaks along with the estimated charge state, we can estimate several features previously discussed relating to the number of labeled atoms in the peptide sequence.

2.4 Shape probabilities features

For shape, we mean the relative intensity patterns of the peak distributions. We use the shape classifier as in our previous work that uses an array of weighted nearest neighbor classifiers that are trained based upon the ratios of the peaks relative to the highest peak within the proposed isotopic distribution. We also derive a feature that distinguishes between the light and heavy intensity patterns using the probability from a classifier [(Nearest neighbor, Linear and Radial SVMs and Probabilistic Trees (J48)] that gives best area under the precision (APR) recall curve. We realize that another shape method that could be used is to calculate exact isotopic distributions using a method such as Mercury using averagine molecular compounds around the mass of the observed isotopic distribution (Rockwood et al., 1996; Rockwood and Haimi, 2006; Senko et al., 1995). In the future we would like to see if using the ‘averagine’ isotopic distribution shapes as a feature in the isotopic distribution and the matched pair annotation algorithms further improves upon our current results (Horn et al., 2000).

2.5 Mass-to-charge and mass differences

We generate features that calculate the m/z and mass differences between the light and heavy monoisotopic peaks. We also create features that are the ratio of the difference over the light m/z and mass, respectively.

2.6 Overall classification

We build a naïve Bayes classifier using these features as previously discussed, binning features to optimize their APR curve from the training data (Davis and Goadrich, 2006; McIlwain et al., 2007). We also introduce two rules into the classifier that state if (1) the calculated charge state between the two pairs are different or (2) if the calculated number of nitrogens is below the value of a 2+0.00613*masslightmonoisotope or above 2+0.0256 *masslightmonoisotope, then return a score 0.0, i.e. −∞ for log probability. These limits are estimated from the nitrogen/mass density of a peptide of all tryptophan (min) or all arginine (max). The log of the probability is used for the G(i, j). Using a naïve Bayes model, we can assign probabilities to the importance of each of these features for determining the overall probabilities for the G(i,j) matrix. We then can build the M(j) matrix from Equations (1–7) to yield the isotopic distribution match map.

3 METHODS

The mass spectra used for training and testing of our algorithms were obtained from LC-MALDI analysis of a 1:1 mixture of unlabeled and metabolically labeled Arabidopsis proteins. Briefly, Arabidopsis seedlings were grown in liquid culture containing either natural abundance or 15N-labeled MS salts, as described previously (Huttlin et al., 2007; Nelson et al., 2007). Labeled and unlabeled plants were combined at a 1:1 ratio based on plant weight at harvest, prior to subcellular fractionation and tryptic digestion of cytosolic proteins. Peptides were separated via nano-scale reversed phase chromatography using an Agilent 1100 nano-HPLC and spotted onto MALDI plates (1050 spots collected over 210 min) using an Agilent fraction collector equipped with MALDI target adapters.

Mass spectrometry analysis was performed using an Applied Biosystems 4800 TOF–TOF. Each MS spectrum was internally calibrated using a singly charged ACTH peptide (m/z 2465.199) which was introduced into each sample during MALDI spotting. Spectra were processed into peak lists using those following centroiding and noise threshold parameters: minimum signal-to-noise ratio: 5; local noise window width: 250 m/z and minimum peak width at FWHM (bins): 2.7. Peak lists were exported from the instrument database using the freely distributed program T2DExtractor2.0 developed by Takis Papoulias at the University of Michigan (www.proteomecommons.org).

Spectra were selected randomly for analysis from throughout the LC gradient, providing spectra of varying complexity. Peaks from each spectrum were grouped into isotopic distributions through visual inspection and isotopic distributions from labeled and unlabeled forms of the same peptide were matched. A total of 41 spectra containing 713 distributions and 255 pairs were used in this analysis.

We generate examples for each spectrum by matching each isotope with every other isotope within the spectrum. This generates n(n−1)/2 examples. Positive examples are those matched pairs that are actually matched whereas the negative examples are the pairs that are actually unmatched. For the expert and machine selected peak experiments (Section 1), we also perturb the isotopic distributions as in our previous work of the actual isotopic matches to generate examples. In this case negative examples are those that are missing the monoisotopic peak in either isotope of the match, and the rest as positive examples.

We build our naïve Bayes model using a training set built from the features generated as described previously. To score the generated isotopic match map, we use three different metrics. We call them the absolute match, monoisotopic match, and monoisotopic fine match scores. The absolute metric is the exact match with all of the isotopic peaks from both the light and heavy distributions. The second metric measures whether the match contains the correct monoisotopic peaks. The third metric requires matching the correct monoisotopic peak and gives further credit for finding additional peaks that belong to the matched isotopic pair. For each score, we define the four quadrants of a contingency table, or confusion matrix. From these confusion matrices, we can calculate performance points.

Absolute match scores: This is the most stringent score, in that it requires that all of the peaks within the matched isotopic pairs are found and having no extraneous peaks. We utilize an absolute score method yielding the following counts for a confusion matrix.

True positive—exact match appears in the map.

True negative—mismatch does not appear in the map.

False positive—mismatch appears within the map.

False negative—exact match does not appear within the map.

Monoisotopic match scores: The absolute score counts an isotopic matched pair annotation wrong even if it misses one peak or includes one extraneous peak (for example a noise peak). Nevertheless, a mostly correct match is often very useful as feature for machine learning or in approaches to quantitative mass spectrometry. This score provides the bare minimum requirement of correctly matching the monoisotopic peaks of the match:

True positive—match correctly contains the monoisotopic peaks of the light and heavy isotopes.

True negative—mismatch between two monoisotopic peaks not found in the map.

False positive—mismatch of the monoisotopic peaks of the light and heavy between two distributions found in the map.

False negative—actual matched monoisotopic peaks not found within the map.

Monoisotopic fine match scores: The previous is the bare-minimum requirement for annotation. However, we would like to give more credit if more peaks within the paired isotopic distributions are found. Therefore, we introduce a third metric, which gives credit per peak if it is within the match that has the correct monoisotopic peaks found.

True positive—peak belongs to the matched pair, and is predicted in a distribution that has the monoisotopic peaks appropriately matched

True negative—peak is not in a match and is not found in a matched isotopic distribution.

False positive—peak does not belong to an isotopic distribution and is predicted as in a distribution or is in an isotopic distribution that is incorrectly matched by their monoisotopic peaks.

False negative—peak belongs to a matched isotopic pair but not found within the map.

3.1 Training and validation

To compare the dynamic programming algorithm against the classifier, we devise a greedy algorithm based upon the classifier probabilities. In this algorithm, we calculate the probabilities for all possible isotopic distribution pairs. We then iteratively annotate pairs in order of highest probability, making sure that no isotopic distribution is assigned to more than one pair. We also threshold the probability at which further pairs are added.

We train the classifier, perfect, expert peak-picked and machine peak-picked algorithms using simplex with an array of values for γp (0−1.0 step 0.1). We optimize γp by maximizing the monoisotope fine match F1-score for the training spectra. We perform 10-fold cross-validation by spectrum, calculating the F1-score points and 95% confidence intervals for the three metrics described previously. We train the isotopic distribution annotation algorithm on each fold as well.

We modify the isotope distribution annotation algorithm's generation of the possible isotopic peak groups from an exhaustive search to look for ‘valid’ isotopic peak groups. By ‘valid’, we mean that the peaks are evenly spaced in their m/z values (within a tolerance of 150 p.p.m.), having a calculated charge state within 1–3 and having more than one peak.

For the expert selected peaks, we use a linear SVM to estimate the probabilities and a search bound of 10. For the machine selected data, we use the naïve Bayes algorithm as described in our previous paper. We also tune the noise algorithm using simplex with a grid of initial values (noise penalty 0-1.0 step 0.1, noise threshold 0-1.0 step 0.1) and using search bounds of 8–12. We optimize monoisotope fine isotope F1-score for the training spectra.

Monoisotopic fine scores: This metric improves upon the monoisotopic score described last year. We assign credit to a peak if it is annotated with a distribution that contains the correct mono-isotopic peak. This is a peak-based metric.

True positive—peak is actually in an isotopic distribution and predicted as in the distribution with the correct monoisotopic peak.

True negative—peak is actually not in an isotopic distribution and not predicted as in an isotopic distribution.

False positive—peak is actually not in an isotopic distribution but predicted as in an isotopic distribution.

False negative—peak is actually in an isotopic distribution but not predicted in an isotopic distribution or peak is in a distribution that contains the incorrect monoisotopic peak.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

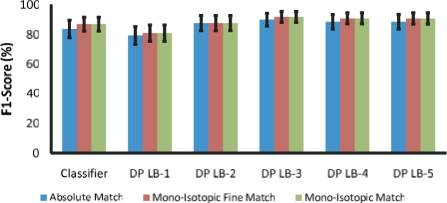

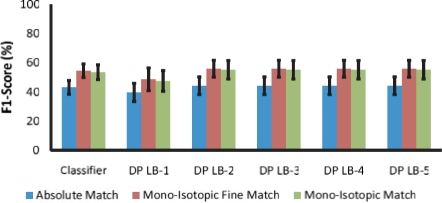

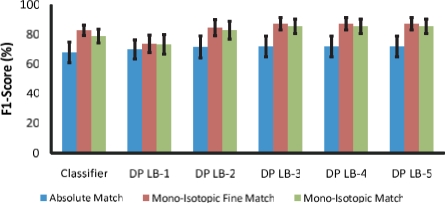

The statistical results for the expert isotope annotated, expert peak selected and machine selected are in Tables 2–4, respectively. The F1-scores are displayed in Figures 3–5, respectively. Looking at the isotope annotation algorithm's scores in Table 5, an improved isotopic distribution map is needed in order to ensure a good match map. We could also improve results by making the isotope match algorithm more ‘tolerant’ of the isotope annotation algorithm's mistakes. We now present our changes to the algorithm that address these issues. Recently, we have made some changes to the isotopic match pair annotation algorithm that significantly improves upon the F1-score for the monoisotopic match and the monoisotopic fine match scores. This improvement as shown in Table 6 is due to changes to our method of example generation and using a regression function in place of the classifier for both the isotopic group and isotopic matched pairs annotation algorithms. These results are based upon the machine-selected peaks using the dynamic programming algorithm with a look back of three. We now explain our changes to the algorithm in further detail.

Table 3.

Statistical results of classifier and dynamic programming algorithms using expert selected peaks (see Section 3 for the distinction between the scores)

| Recall | Precision | F1 | FPR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute match | ||||

| Classifier | 70±6 | 67±9 | 68±7 | 1±0.3 |

| 3-Step look back | 77±5 | 68±9 | 72±7 | 1±0.3 |

| Monoisotopic match | ||||

| Classifier | 81±5 | 77±7 | 79±5 | 0.9±0.3 |

| 3-Step look back | 91±3 | 81±8 | 86±5 | 0.8±0.3 |

| Monoisotopic fine match | ||||

| Classifier | 81±4 | 86±7 | 83±3 | 40±17 |

| 3-Step look back | 89±2 | 86±7 | 87±4 | 44±15 |

Table 2.

Statistical results of classifier and dynamic programming algorithms using expert annotated isotopes (see Section 3 for the distinction between the scores)

| Recall | Precision | F1 | FPR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute match | ||||

| Classifier | 86±6 | 83±8 | 84±6 | 0.7±0.3 |

| 3-Step look back | 99±2 | 83±7 | 90±4 | 0.7±0.3 |

| Monoisotopic match | ||||

| Classifier | 86±6 | 83±8 | 84±6 | 0.7±0.3 |

| 3-Step look back | 99±2 | 83±7 | 90±4 | 0.7±0.3 |

| Monoisotopic fine match | ||||

| Classifier | 87±5 | 88±7 | 87±5 | 38±19 |

| 3-Step look back | 99±1 | 86±6 | 92±4 | 49±14 |

Table 4.

Statistical results of classifier and dynamic programming algorithms using machine selected peaks (see Section 3 for the distinction between the scores)

| Recall | Precision | F1 | FPR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute match | ||||

| Classifier | 35±4 | 58±8 | 43±5 | 1±0.4 |

| 3-Step look back | 36±6 | 59±9 | 44±6 | 1±0.4 |

| Monoisotopic match | ||||

| Classifier | 43±4 | 72±10 | 54±5 | 0.7±0.4 |

| 3-Step look back | 45±6 | 74±10 | 55±6 | 0.7±0.4 |

| Monoisotopic fine match | ||||

| Classifier | 43±5 | 77±8 | 55±5 | 6±2 |

| 3-Step look back | 44±6 | 78±8 | 56±6 | 6±2 |

Fig. 3.

F1-scores using expert-annotated isotopes. DP-LB-X stands for the dynamic programming algorithm with look back of X.

Fig. 5.

F1-scores using machine-selected peaks.

Table 5.

Statistical results of isotope annotation algorithm using expert and machine selected peaks [see (McIlwain et al., 2007) and Section 3.1 for the distinction between the scores]

| Recall | Precision | F1 | FPR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute isotope | ||||

| Expert selected peaks | 91±3 | 98±2 | 94±2 | 0.4±0.4 |

| Machine selected peaks | 59±5 | 87±3 | 70±6 | 2±0.4 |

| Monoisotopic isotope | ||||

| Expert selected peaks | 99±1 | 95±3 | 97±1 | 2±1 |

| Machine selected peaks | 76±6 | 72±8 | 73±6 | 3±0.4 |

| Monoisotopic fine isotope | ||||

| Expert selected peaks | 97±2 | 100±0 | 98±1 | 0±0 |

| Machine selected peaks | 78±4 | 75±7 | 76±5 | 18±3 |

Table 6.

Statistical results of regressor and dynamic programming algorithms using machine-selected peaks

| Recall | Precision | F1 | FPR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute match | ||||

| Unweighted recall | 43±5 | 49±6 | 45±4 | 2±1 |

| Weighted recall | 50±5 | 48±7 | 48±4 | 2±1 |

| Mono-isotopic Match | ||||

| Unweighted recall | 59±6 | 67±8 | 62±5 | 1±0.4 |

| Weighted Recall | 65±6 | 63±9 | 63±5 | 2±1 |

| Monoisotopic fine match | ||||

| Unweighted recall | 73±5 | 80±7 | 76±4 | 8±2 |

| Weighted recall | 79±5 | 75±8 | 76±4 | 12±3 |

In the previous paper, we generated the negative ‘near-miss’ isotopes by perturbing the isotopic distribution, and marking them as entirely incorrect. However, these perturbed isotopic distributions are mostly correct. To capture this information, we now use a continuous output label (0–1), where 0 is a true negative, 1 is a true positive and the values between are a measure of how close the isotopic distribution is to the expert's annotation. This score between the actual and predicted isotopic groups is calculated using the following equation:

| (31) |

Where P is the predicted isotopic distribution, T is the true isotopic distribution, Nm is the number of matching peaks between T and P and NP and NT are the number of peaks in P and T, respectively. We predict this score from the features with a regression function and replace the S(i,j) with the log score. We then use the search algorithm for finding the all possible isotopic distributions to train the regression function.

We utilize the same idea for the matched isotope pairs. We now calculate a measure of how close the isotopic pair is to the expert given annotation with the equation:

| (32) |

So SM gives a score between the true and predicted isotopic pair based upon the lowest SI score of the left and right isotopic distributions. Again, we train a regression function that will predict this score from the features. To generate the examples for the matched pairs, we score all valid isotopic pairs (i.e. the charge states are equal, and the number of nitrogens are within the tolerances as described in Section 2.1), using the possible isotopes generated previously. The G(i,j) in the dynamic programming algorithm is now the log of SM.

The results in Table 6 are obtained using the M5Prime regression tree model from the Weka library (Wang and Witten, 1997; Witten and Frank, 2000). To improve recall at the cost of precision we tune the algorithm with a weighted F1-score:

| (33) |

Where w=0.125 for the weighted and w=1.0 for the unweighted results. We also tune using the same grid of parameters without the simplex method.

5 RELATED WORK

The Prosight PTM system is slightly related to our method (Zamdborg et al., 2007), which makes protein and protein modification identifications from mass spectra. We would like to state however, that our problem is unique in that it has ‘unnatural’ isotopic distribution due to the metabolic label.

6 FUTURE WORK

As seen in Figures 3 and 4, the algorithms perform well in the absence of noise peaks (Fig. 5). Trying a different isotopic annotation method or improving the current one should improve our results. Also, efforts to improve the matching algorithm's tolerance of isotopic annotation errors would be beneficial. Trying other types of classifiers or regressors for estimating the score of a matched isotopic distribution might also improve performance.

Fig. 4.

F1-scores using expert-selected peaks.

Once we have an algorithm that annotates the matched isotopic distribution pairs accurately, we will then be able to apply it in a number of contexts to aid in peptide identification and quantification. Most obviously, once we can match heavy and light isotopic distributions for unknown peptides, we will be able to quantify changes in abundance prior to identification. When using instruments such as TOF–TOF mass spectrometers for which MS and MS/MS data acquisition is decoupled, we will be able to identify differentially expressed proteins within complex mixtures and specifically target them for subsequent identification. This should ultimately allow much more rapid identification of biologically interesting proteins without extensive characterization of unchanging proteins.

When mature, our novel approach for identifying pairs of labeled and unlabeled isotopic distributions will aid in peptide identification as well. Once labeled and unlabeled distributions are identified, the number of labeled atoms (nitrogens in our case) may be inferred. We can then use this additional piece of information as another constraint when we try to identify each peptide via conventional algorithms such as Mascot (Perkins et al., 1999), MS-Fit (Clauser et al., 1999), and SEQUEST (Eng et al., 1994). By allowing us to exclude many wrong identifications on the basis of molecular formula, this should allow us to improve the sensitivity and specificity of our identifications. Though the advantages of sequence constraints such as these have been demonstrated several times in the literature (Hegeman et al., 2007; Nelson et al., 2007; Pratt et al., 2002; Snijders et al., 2005; Zhong et al., 2004), our present work represents the first step toward an automated algorithm that would enable application of these constraints on a truly proteomic scale.

7 CONCLUSION

This article has presented classification and regression models for assigning scores to potential, matched isotopic distribution pairs in mass spectra. We showed how performance of this model can be further improved by dynamic programming to map a spectrum into its matched isotopes. Improving the isotope annotation method and the tolerance of the match finding algorithm should improve our results for finding matched pairs. Most importantly, we presented a new problem in mass spectrometry and provide a baseline method for analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr Amy Harms and Dr Gregory Barrett-Wilt of the UW-Madison Biotechnology Center Mass Spectrometry Facility for access to instrumentation and assistance with LC-MALDI experiments. They would also like to thank Angela Walker and Takis Papoulias of the University of Michigan for assistance with T2DExtractor2.0. E.L.H. was supported by a UW-Madison College of Agricultural and Life Sciences graduate fellowship.

Funding: This work is supported in part by the NLM training grant 5T15LM00739, NSF grant 0534908, and NIH training grant 5-T32-GM08349. Portions of this work were supported by funds from the NSF (MCB-0448369).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Babnigg G, Giometti CS. Proteome web: a web-based interface for the display and interrogation of proteomes. Proteomics. 2003;3:584–600. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beynon RJ, Pratt JM. Metabolic labeling of proteins for proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2005;4:857–872. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R400010-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe LH, et al. A comparison of the consistency of proteome quantitation using two-dimensional electrophoresis and shotgun isobaric tagging in Escherichia Coli cells. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:2437–2449. doi: 10.1002/elps.200410336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauser KR, et al. Role of accurate mass measurement (+/− 10 ppm) in protein identification strategies employing MS or MS/MS and database searching. Anal. Chem. 1999;71(14):2871–2782. doi: 10.1021/ac9810516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven M, et al. Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology. Menlo Park, CA: AAAI Press; 2000. A probablistic learning approach to whole-genome operon prediction; pp. 116–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Goadrich M. ICML'06: Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning. New York: ACM Press; 2006. The relationship between precision-recall and ROC curves; pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- DeSouza L, et al. Search for cancer markers from endometrial tissues using differentially labeled tags itraq and cicat with multidimensional liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 2005;4:377–386. doi: 10.1021/pr049821j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domon B, Aebersold R. Mass spectrometry and protein analysis. Science. 2006;312:212–217. doi: 10.1126/science.1124619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng JK, et al. An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory MR, et al. Advances in quantitative proteomics using stable isotope tags. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20(suppl. 12):S23–S29. doi: 10.1016/s1471-1931(02)00203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guina T, et al. Proteomic analysis of pseudomonas aeruginsosa grown under magnesium limitation. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2003;14:742–751. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(03)00133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gygi SP, et al. Quantitative analysis of complex protein mixtures using isotope-coded affinity tags. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999;17:994–999. doi: 10.1038/13690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han DK, et al. Quantitative profiling of differentiation-induced microsomal proteins using isotope-coded affinity tags and mass spectrometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:946–951. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt M, et al. Assessing the effects of diurnal variation on the composition of human parotid saliva: quantitative analysis of native peptides using itraq reagents. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:4947–4954. doi: 10.1021/ac050161r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegeman A, et al. Stable isotope assisted assignment of elemental compositions for metabolomics. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:6912–6921. doi: 10.1021/ac070346t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn DM, et al. Automated reduction and interpretation of high resolution electrospray mass spectra of large molecules. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2000;11:320–332. doi: 10.1016/s1044-0305(99)00157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttlin EL, et al. Comparison of full versus partial metabolic labeling for quantitative proteomics analysis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2007;6:860–881. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600347-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krijsveld J, et al. Metabolic labeling of C. elegans and D. melanogaster for quantitative proteomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:927–931. doi: 10.1038/nbt848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlwain S, et al. Using dynamic programming to create isotopic distribution maps from mass spectra. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:i328–i336. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CJ, et al. Implications of 15N-metabolic labeling for automated peptide identification in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proteomics. 2007;7:1279–1292. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DN, et al. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence data bases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt J, et al. Stable isotope labeling in vivo as an aid to protein identification in peptide mass fingerprinting. Proteomics. 2002;2:157–163. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200202)2:2<157::aid-prot157>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranish JA, et al. The study of macromolecular complexes by quantitative proteomics. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:349–355. doi: 10.1038/ng1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood AL, et al. Ultrahigh resolution isotope distribution calculations. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1996;10:54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood AL, Haimi P. Efficient calculation of accurate masses of isotopic peaks. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross PL, et al. Multiplexed protein quantitation in saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2004;3:1154–1169. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400129-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadygov RG, et al. Large-scale database searching using tandem mass spectra: looking up the answer in the back of the book. Nat. Methods. 2004;1:195–202. doi: 10.1038/nmeth725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senko MW, et al. Determination of monoisotopic masses and ion populations for large biomolecules from resolved isotopic distributions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1995;6:229–233. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(95)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiio Y, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of myc oncoprotein function. EMBO J. 2002;21:5088–5096. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiio Y, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of chromatin-associated factors. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2003;14:696–703. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(03)00204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders A, et al. Novel approach for peptide quantitation and sequencing based on 15N and 13C metabolic labeling. J. Proteome Res. 2005;4:578–585. doi: 10.1021/pr0497733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Haller PD, et al. The application of new software tools to quantitative protein profiling via icat and tandem mass spectrometry: I. statistically annotated data sets for peptide sequences and proteins identified via the application of icat and tandem mass spectrometry to proteins co-purifying with t cell lipid rafts. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2003a;2:426–447. doi: 10.1074/mcp.D300002-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Haller PD, et al. The application of new software tools to quantitative protein profiling via icat and tandem mass spectrometry: Ii. evaluation of tandem mass spectrometry methodologies for large-scale protein analysis and the application of statistical tools for data analysis and interpretation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2003b;2:428–442. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300041-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Witten IH. In Proceedings of the poster papers of the European Conference of Machine Learning. Prague: University of Economics, Faculty of Informatics and Statistics; 1997. Induction of model trees for predicting continuous classes. [Google Scholar]

- Witten IH, Frank E. Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools with Java Implementations. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufman; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zamdborg L, et al. ProSight PTM 2.0: improved protein identification and characterization for top down mass spectrometry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(suppl. 2):W701–W706. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, et al. Two-dimensional mass spectra generated from the analysis of 15N-labeled and unlabeled peptides for efficient protein identification and de novo peptide sequencing. J. Proteome Res. 2004;3:1155–1163. doi: 10.1021/pr049900v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]