Abstract

Summary: The wcd system is an open source tool for clustering expressed sequence tags (EST) and other DNA and RNA sequences. wcd allows efficient all-versus-all comparison of ESTs using either the d 2 distance function or edit distance, improving existing implementations of d 2. It supports merging, refinement and reclustering of clusters. It is ‘drop in’ compatible with the StackPack clustering package. wcd supports parallelization under both shared memory and cluster architectures. It is distributed with an EMBOSS wrapper allowing wcd to be installed as part of an EMBOSS installation (and so provided by a web server).

Availability: wcd is distributed under a GPL licence and is available from http://code.google.com/p/wcdest

Contact: scott.hazelhurst@wits.ac.za

Supplementary information: Additional experimental results. The wcd manual, a companion paper describing underlying algorithms, and all datasets used for experimentation can also be found at www.bioinf.wits.ac.za/~scott/wcdsupp.html

1 INTRODUCTION

The clustering of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) is an important tool to understand the transcriptome. wcd is an open-source program which can be used to cluster large sets of ESTs, and is adaptable to shorter length error prone novel sequence technologies such as Solexa and 454. We have used wcd successfully to cluster low-pass genomic data as well as mixed EST and RNA sequences.

ESTs are on average 300 to 500 base pairs in length. As high-throughput technology is used to produce them, they are relatively error prone. The goal of EST clustering is to group ESTs according to their parent gene, i.e. two ESTs should be in the same cluster if they are products of the same gene. We employ a single linkage algorithm: initially each sequence is put in a singleton cluster, and then pairs of sequences are compared; if they have a sufficiently large overlap (or a sufficiently large approximate overlap), the clusters to which they belong are merged. Single linkage tends to produce elongated clusters, appropriate for the task at hand.

Computationally, the problem can be represented as a graph problem. The ESTs form the vertex set, and two vertices are connected if and only if they have an overlap. The clusters then are the connected components. The computational cost is determining which vertices are connected by edges (since potentially there are a quadratic number of comparisons).

Some popular tools for EST clustering are PaCE (Kalyanaraman et al., 2003), ESTate (Slater, 2000) and xsact (Malde et al., 2003). The assembler, CAP3, is also often used (Huang and Madan, 1999). Our tool compares favourably to these, as demonstrated in Section 3. For a recent overview of EST clustering issues and tools (Nagaraj et al., 2007).

2 OVERVIEW OF WCD

In order to decide whether two ESTs have a sufficiently large approximate overlap, we have to decide: how long the overlap should be (the window size); how we measure similarity or difference (what we mean by approximate); and what the error threshold should be (just how similar we want them to be). All of these are parameters of the clustering process. In addition, wcd provides a number of different features and ways in which the user can control clustering. Most of these are parameterizable.

2.1 Choice of distance function

wcd provides two ways of comparing ESTs for overlap. The default distance function used is the d2 distance function (Hide et al., 1994), a biologically validated distance function for EST comparison, and is particularly insensitive to repeats and rearrangement. wcd has an efficient, published implementation of the d2 distance function (Hazelhurst, 2008). The user can specify word length, window size and error threshold. A memory efficient implementation of edit distance (Smith–Waterman) is also provided. The user may give the penalty matrix and threshold or use the defaults provided.

2.2 Heuristics for speedup

The computation of d2 and edit distance are both expensive (quadratic in sequence length). wcd provides parameterizable heuristics which filter out unnecessary comparisons and speedup the clustering. Empirical testing has shown that the default parameters of the heuristics are very conservative: they do not affect the quality of the results, while speeding up the clustering by an order of magnitude. However, more aggressive parameters can speedup the clustering significantly and have a much smaller impact on the quality results than small changes to other parameters. In practice, clustering often has to be performed several times as the user explores different parameters or isolates problems in the data (such as low complexity regions and vector contamination not captured by available screening databases). Using aggressive heuristics for these early phases is particularly useful.

2.3 Merging, adding, constraining

Incremental clustering is supported: two independently clustered sets can be merged, and new sequences added to previously clustered sets. wcd will perform this merging and addition efficiently without unnecessary comparisons. Other user constraints which allow additional information (such as clone pairs) can be provided.

2.4 Reclustering—refinement of clusters

wcd supports successive refinement of clusters through reclustering. An initial fast but coarse clustering produces ‘super-clusters’. The next step refines the super-clusters using a more accurate (and expensive) clustering step, possibly breaking the super-clusters into separate clusters. The rationale is that the basic clustering algorithm is quadratic in the number of sequences being clustered. If the initial super-clustering can be performed in sub-quadratic time, a reclustering will be much more efficient than a de novo clustering.

wcd also has a suffix-array-based algorithm for coarse clustering. This takes the raw sequence data and its suffix array to produce super-clusters based on the existence of common words of length k. wcd uses the sary suffix array package (http://sary.sourceforge.net) and has Python scripts to transform data. The word length can be chosen by the user but empirical testing showed that choosing k in the range 25–30 is conservative.

2.5 Parallelization

wcd has two modes for parallelization: distributed memory on a cluster of workstations, and a shared memory mode for symmetric multiprocessors. These two are integrated and wcd works well for a cluster of shared memory machines.

With the wcd MPI implementation for a cluster of workstations, effective parallelization has been achieved for large real datasets by well above 100 nodes (see Section 3). Its Pthreads implementation for multicore architectures, on the other hand, achieves reasonable speedup for up to 5 cores.

2.6 Integration with StackPack

wcd has been designed to integrate transparently with the StackPack system (Miller et al., 1999; Reed, 2001), a widely used management system for EST reconstruction. wcd seamlessly replaces the proprietary d2-cluster algorithm within this package.

2.7 EMBOSS wrapper

We implemented an EMBOSS wrapper for wcd which allows it to be installed as part of an EMBOSS system. This allows wcd to be provided by a web server to local or remote users via a GUI.

2.8 Other

There are further command line options that allow the user to produce output in different formats, produce statistics of the clustering results and explore the dataset.

There is a comprehensive manual distributed as a texinfo file from which PDF, html and an info page are produced on installation. A full description of the underlying algorithms can be found in a companion paper found in the Supplementary Material.

3 EVALUATION

The current version of wcd is stable and has been tested on a wide variety of datasets and used in a number of projects clustering human (Imanishi et al., 2004), barley and rice ESTs and metagenomic data. Here we supply some comparative data with other popular EST clustering tools as well as data on performance (for more, see the Supplementary Material).

We used the default parameters of each tool. A change of clustering parameters can make a very big difference to clustering quality; however, a much larger study would be needed to isolate the effect of (a) the clustering parameters, (b) the heuristics used and (c) the basic distance functions used. The results below show that wcd is a good method for clustering of ESTs. However, as we have only tested each tool using its default parameters, we do not claim on this evidence superiority of wcd.

Our two main datasets used for testing are two sets of Arabidopsis thaliana ESTs that we call A686904 and A076941. The former is a set of 686 904 ESTs (all the A.thaliana ESTs in Genbank 162 between 100 and 700 bp in length). A subset of 76 941 ESTs were selected for reference purposes.

3.1 Clustering quality on real data

We evaluated the output of four EST clustering tools. As the results of clustering are typically given to an assembler, we also compare to the CAP3 assembler. For data we used the A076941 set, and created a reference clustering by using the assignment of these ESTs to the tentative consensus (TC) sequences of the Arabidopsis Gene Index as cluster membership (Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi). The quality of the clusterings produced by the tools was compared to the reference clustering using sensitivity (SE) and the Jaccard index (JI). SE is the most important evaluation criterion for EST clustering: incorrectly clustering sequences together can be remedied at a later stage but incorrectly separating them cannot. SE is defined as tp/(tp+fn) (tp=true positives, fn=false negatives). JI balances SE and the number of false positives, and is defined as tp/(tp+fn+fp) (fp=false positives).

The method of using the TC assignment as clustering reference favours techniques that are less sensitive, because in sequence assembly, fewer sequences need to be grouped together than in EST clustering, e.g. products of alternative splicing.

Table 1 shows the relative performance of CAP3, wcd and PaCE on the full A076941 set. Table 1 (Panel a) shows the quality of the clusters produced by wcd, PaCE and CAP3 compared to the reference set. The clone-linking options of both tools were not used in order to test their capacity to analyse sequence data. wcd remains significantly more sensitive than the others. However, as wcd is more sensitive, there are more false positives and so the JI for wcd drops. Maximum cluster size remains modest though (1.7% of the set) and so the increased SE will not create significant extra burden for the assembler. Table 1 (Panel b) shows the comparison of wcd and PaCE with respect to CAP3, and shows the quality of the clustering produced by wcd and PaCE by themselves, and then the quality of first using the clustering tool and then giving the individual clusters to CAP3.

Table 1.

Quality assessment on the A076941 set

| SE |

JI |

|

|---|---|---|

| Panel a: Quality against reference set | ||

| wcd | 0.933 | 0.476 |

| PaCE | 0.835 | 0.636 |

| CAP3 | 0.739 | 0.719 |

| Panel b: Quality against CAP3 | ||

| wcd | 0.994 | 0.401 |

| PaCE | 0.926 | 0.589 |

| wcd+CAP3 | 0.993 | 0.980 |

| PaCE+CAP3 | 0.853 | 0.828 |

We carried out further tests using seven non-overlapping subsets of A076941 to assess variability and to compare to the quality of ESTate and xsact (which are not capable of clustering the full set on our machine). Each subset was 10 k sequences (4M bp). Table 2 reports SE and the JI. The variability of the results shows the need to use several, diverse datasets for a full evaluation.

Table 2.

Sensitivity and Jaccard index on subsets of A076941 set

| CAP3 |

Estate |

PaCE |

wcd |

xsact |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | |||||

| 1 | 0.659 | 0.709 | 0.632 | 0.809 | 0.834 |

| 2 | 0.659 | 0.747 | 0.662 | 0.853 | 0.864 |

| 3 | 0.666 | 0.905 | 0.847 | 0.950 | 0.959 |

| 4 | 0.705 | 0.831 | 0.759 | 0.900 | 0.941 |

| 5 | 0.800 | 0.907 | 0.859 | 0.960 | 0.969 |

| 6 | 0.813 | 0.897 | 0.886 | 0.978 | 0.982 |

| 7 | 0.821 | 0.878 | 0.841 | 0.917 | 0.929 |

| Jaccard index | |||||

| 1 | 0.649 | 0.439 | 0.672 | 0.478 | 0.230 |

| 2 | 0.650 | 0.541 | 0.673 | 0.702 | 0.250 |

| 3 | 0.653 | 0.657 | 0.615 | 0.768 | 0.585 |

| 4 | 0.656 | 0.456 | 0.656 | 0.828 | 0.413 |

| 5 | 0.782 | 0.539 | 0.542 | 0.577 | 0.235 |

| 6 | 0.796 | 0.713 | 0.700 | 0.504 | 0.247 |

| 7 | 0.819 | 0.759 | 0.837 | 0.903 | 0.756 |

3.2 Curated EST set

Using Ensembl, we randomly selected 34 non-overlapping genes on the mouse chromosome 4, and used BLAST in dbEST to find ESTs that matched, producing in total 2294 ESTs. We created four reference clusterings M60, M100, M150 and M200: in clustering Mx, all ESTs that matched a particular gene with at least a score of x were clustered together. Performance of PaCE and wcd are similar, with SE and JI both in the range 0.58–0.75, with wcd having slightly higher indices on all sets (data shown in Supplementary Material).

3.3 Robustness

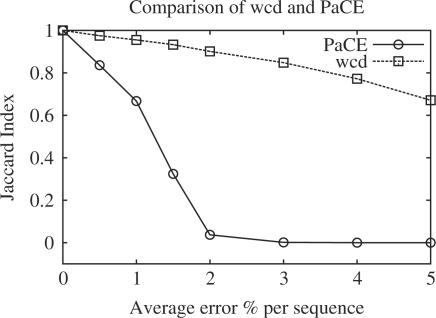

To test the robustness of the algorithm, we took the Public Cotton Dataset (about 30 000 sequences), then generated variants of this dataset by introducing different error rates at random. We then computed the JI of the sets with errors against the original set. The results are shown in Figure 1. They show that under the default parameters that wcd is more robust and capable of handling errors in datasets without loss of accuracy.

Fig. 1.

Robustness: Jaccard index of clusters from error sets with respect to original cluster.

In another experiment, we produced four series of artificial datasets with different error models, using the ESTsim tool (Hazelhurst and Bergheim, 2003). Each series consists of 16 EST files, each roughly 25 k sequences (10 M bp). The results, found in the Supplementary Material, show that with their default parameters wcd and PaCE produce clusters of similar quality, but as the error rate in the data increases wcd's performance drops more gracefully.

3.4 Computational performance analysis

The time taken to cluster ESTs is a function of the number of sequences and the number of bases (usually quadratic). It also depends on the actual data being clustered: ESTs that form many, smaller clusters usually will be much faster to cluster than those that form few big clusters. For this reason, it is important to base analyses on using several, different EST sets.

Single processor For our main study we used the A686904 set with a total of about 687k sequences/295M bp. We clustered the full set, and to explore the scalability of the algorithm also clustered subsets of ∼9.5k sequences/4M bp (70 subsets), 19k sequences/8M bp (35 subsets), 38k sequences/16M bp (17 subsets), 76k sequences/32M bp (8 subsets), 153k sequences/64M bp (4 subsets), 307k sequences/128M bp (2 subsets) and 613k sequences/256M bp.

The table below shows the performance of wcd in single CPU mode (Intel 2.33 GHz E5345, with 4G of RAM, 4M of L2-cache) for the different sizes; for the smaller sizes, the time shown is the average over all subsets. The time ranges from 10 s for a 4M file to just under 15 h for a 295M file. For the full A686904 set, memory usage is 166M (resident set size).

| Size | 4M | 8M | 16M | 32M | 64M | 128M | 256M | 295M |

| Time (s) | 9.7 | 38 | 159 | 631 | 2562 | 10413 | 42936 | 53286 |

For a performance comparison study, we used smaller datasets, since some of the other EST clustering tools had memory problems. Below we report runtimes (in seconds) and resident set size for wcd, CAP3, ESTate and xsact on the same system. For this comparison, we used the seven subsets of A076941 set described above (10k/4M bp each), and two publicly available datasets: the SANBI10000 dataset (10k sequences, 3.7M bp) and the Public Cotton set (30k sequences, 17M bp). On the Public Cotton set, ESTate and xsact ran out of memory; PaCE is not designed to run on a single processor.

| dataset | wcd | CAP3 | ESTate | xsact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis | ||||

| subsets (ave.) | 8.62s/4M | 309s/160M | 72s/64M | 42s/1.9G |

| SANBI10000 | 7.4s/4M | 75s/59M | 49s/47M | 40s/1.6G |

| Public cotton | 195s/10M | 1470s/530M | – | – |

Parallel mode Our experience is that on large datasets, wcd scales efficiently up to about 100 processors, though modest improvement can be expected after that.

The table below shows the effect of MPI parallelization on the iQudu cluster of the SA Centre for High Performance Computing. The cluster contains 160 nodes, each of which contains two 2.6 GHz AMD Dual-core (2218) Opterons with 16 G of RAM per node, running MVAPICH. We ran wcd in the mode of four MPI processes per node. The table below shows the cost of clustering the A686904 set with different numbers of slaves. The time drops from over 21 h on a single core, to under 15 min on 127 cores.

| # slaves | 1 | 2 | 15 | 31 | 63 | 96 | 127 |

| Time (s) | 76243 | 10652 | 4938 | 2583 | 1411 | 1132 | 878 |

| Efficiency | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 0.68 |

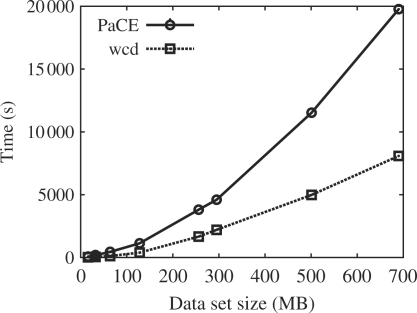

Figure 2 shows the relative performance of different size datasets on the C4 cluster of the Meraka Institute (3.6 GHz Irwindale Xeon CPUs), using 31 slaves for both wcd and PaCE. As data, we used subsets of A686904 up to 295M, and then a mixed set of ESTs added to this to see how performance scaled beyond this point.

Fig. 2.

Relative performance of different size datasets on the C4 cluster.

As can be seen, wcd consistently outperforms PaCE on all dataset sizes. The largest dataset tested the total memory in the cluster—we estimate the memory footprint of PaCE on a 695M dataset as about 95G across the 32 machines. The memory footprint of wcd was under 6G across the machines. However, the structure of the PaCE algorithm implies that beyond the 32 processor limit, it may benefit from the increased memory available much more than wcd and so the results here may not be indicative of PaCE's performance on much larger systems.

One potential explanation for the difference in computational costs is difference in cost between computing edit and d2 distances, but this still needs to be explored.

4 CONCLUSION

We introduced a new EST clustering tool, wcd. It compares well to established tools such as CAP3 and PaCE w.r.t. its clustering quality on real data, while being more robust to errors, as measured by experiments with artificial data. It scales well and can handle very large datasets, as opposed to several of the other EST clustering tools tested. Its small memory footprint means that wcd clusters very large files on a single machine or small cluster, while its MPI parallelization allows it to be deployed effectively on a cluster of 100 or more processors.

4.1 Availability

wcd is available under a GPL licence as an open source tool. It has been tested on different flavours of Linux, Unix and Mac OS X, and on different architectures. The MPI implementation has been tested on multiple MPI versions. It can compile and run in sequential mode without the availability of the Pthreads and MPI headers and libraries so installation is not dependent on these.

4.2 Future work

Future work includes improving the parallel implementation to run well in a heterogeneous and very loosely coupled environments. We are investigating alternative efficient methods of pre-clustering and new heuristics for quick comparison of sequences. Some of the ideas of PaCE and wcd are complementary and it would be worth exploring how they could be combined.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Anton Bergheim, Tania Broveak Hide, Mario Jonas, Gwen Koning, Pravesh Ranchod, Peter van Heusden for help and support. They also would like to thank the SA Centre for High Performance Computing (Jeff Chen, Jeremy Main) and the Meraka Institute (Albert Gazendam) for access to their computing facilities and unstinting help. Ananth Kalyanaraman gave us access to PaCE, technical advice and insightful comments on a draft of this article. Finally, they thank two anonymous referees for their helpful comments.

Funding: This work was supported by the South African National Bioinformatics Network (to S.H.), South African Medical Research Council (to W.H.), South African National Research Foundation (GUN2069114 to S.H.), German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (to Zs.L.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Hazelhurst S. Algorithms for clustering expressed sequence tags: the wcd tool. South African Comput. J. 2008;40 [Google Scholar]

- Hazelhurst S, Bergheim A. Technical Report TR-Wits-CS-2003-1. Johannesburg, South Africa: School of Computer Science, University of the Witwatersrand; 2003. ESTsim: a tool for creating benchmarks for EST clustering algorithms. [Google Scholar]

- Hide W, et al. Biological evaluation of d2, an algorithm for high-performance sequence comparison. J. Comput. Biol. 1994;1:199–215. doi: 10.1089/cmb.1994.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Madan A. CAP3: a DNA sequence assembly program. Genome Res. 1999;9:868–877. doi: 10.1101/gr.9.9.868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi T, et al. Integrative annotation of 21037 human genes validated by full-length cDNA clones. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyanaraman A, et al. Space and time efficient parallel algorithms and software for EST clustering. IEEE T. Parallel Distri. Syst. 2003;14:1209–1220. [Google Scholar]

- Malde K, et al. Fast sequence clustering using a suffix array algorithm. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1221–1226. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R, et al. A comprehensive approach to clustering of expressed human gene sequence: the sequence tag alignment and consensus knowledge base. Genome Res. 1999;9:1143–1155. doi: 10.1101/gr.9.11.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj S, et al. A hitchhiker's guide to expressed sequence tag (EST) analysis. Brief. Bioinform. 2007;8:6–21. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbl015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed G. StackPACK clustering system. Brief. Bioinform. 2001;2:388–404. [Google Scholar]

- Slater G. Ph.D. Thesis. Cambridge: University of Cambridge; 2000. Algorithms for the Analysis of Expressed Sequence Tags. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.