Abstract

Summary: Malin is a software package for the analysis of eukaryotic gene structure evolution. It provides a graphical user interface for various tasks commonly used to infer the evolution of exon–intron structure in protein-coding orthologs. Implemented tasks include the identification of conserved homologous intron sites in protein alignments, as well as the estimation of ancestral intron content, lineage-specific intron losses and gains. Estimates are computed either with parsimony, or with a probabilistic model that incorporates rate variation across lineages and intron sites.

Availability: Malin is available as a stand-alone Java application, as well as an application bundle for MacOS X, at the website http://www.iro.umontreal.ca/~csuros/introns/malin/. The software is distributed under a BSD-style license.

Contact: csuros@iro.umontreal.ca

1 INTRODUCTION

An idiosyncratic feature of eukaryotic gene organization is that the genomic sequences of protein-coding genes are frequently interrupted by non-coding sequences, called introns, which are excised (spliced) from the transcripts prior to translation. Fundamental constituents of the splicing machinery are present throughout main eukaryotic lineages (Collins and Penny, 2005). Intron-containing genes are spread across diverse eukaryotic phyla, and orthologous genes often have similar exon–intron organization even at large evolutionary distances (Rogozin et al., 2003). Accordingly, it is fairly certain that splicing was already present in the last common ancestor of eukaryotes (Rodríguez-Trelles et al., 2006). Gene structures changed to different extents in eukaryotic lineages (Roy and Gilbert, 2006).

Whole-genome sequencing projects have made it possible to perform large-scale phylogenetic analyses that scrutinize the evolution of exon–intron organization. Following the pioneering study by Rogozin et al. (2003), numerous results have appeared (Carmel et al., 2005; Carmel et al., 2007; Csűrös, 2005; Csűrös et al., 2007, 2007; Nguyen et al., 2005; Nielsen et al., 2004; Roy and Gilbert, 2005; Roy and Penny, 2006; Stajich et al., 2007; Sullivan et al., 2006) inferring lineage- and gene-specific features of gene structure evolution, and often describing methodological novelties. This note aims to introduce Malin, a software package developed for the analysis of eukaryotic gene structure evolution.

2 FEATURES

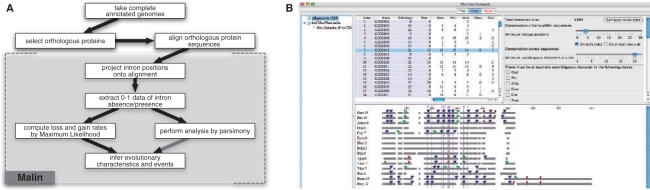

Malin provides a graphical user interface for various tasks commonly used to infer the evolution of exon–intron structure in multiple protein-coding ortholog sets (Fig. 1) along a fixed species phylogeny. The implemented tasks include the following:

Identification of conserved homologous splice sites in annotated protein sequence alignments.

Computation of primary statistics about introns in homologous sites (‘shared introns’).

Estimation of ancestral intron content, intron losses and gains by Dollo parsimony.

Estimation of intron loss and gain rates in a probabilistic model.

Estimation of ancestral intron content, intron losses and gains in a probabilistic model.

Inference of histories at individual or multiple sites.

Error estimation for rates and histories by bootstrap.

Fig. 1.

(A) Typical analysis pipeline for intron evolution. Malin can perform the tasks downstream of ortholog identification and alignment. (B) Alignment panel in Malin. The intron table will be constructed from a set of multiple alignments (corresponding to the rows of the table displayed in the middle on the top), based on conservation criteria specified by the user (through the form on the upper right). The bottom half of the panel plots an illustration for the selected alignment, showing alignment gaps and projected intron sites (colored tags).

Figure 1 illustrates the typical analysis pipeline for eukaryotic gene structure evolution (Rogozin et al., 2005). In order to infer if spliceosomal introns are in homologous positions, splice sites need to be projected onto coding sequences, and then homology is established in conserved regions of the protein alignments. An intron table is constructed from the projected intron annotations. The table is a binary table of intron presence and absence in homologous sites across the studied organisms: Malin can also cope with ambiguous characters. The patterns can be analyzed by Dollo parsimony (Farris, 1977) (assuming that intron gains and losses are rare events), or by probabilistic models of intron evolution. Malin works with the likelihood framework that I have elaborated (Csűrös, 2005; (Csűrös et al., 2007, 2008). The corresponding probabilistic model has branch-specific intron gain and loss rates, as well as rates-across-sites variation.

Malin uses a rates-across-sites Markov model for intron evolution, with branch-specific gain and loss rates. If no rate variation is assumed across the sites, then every branch has just a gain and loss rate, with corresponding gain and loss probabilities. Briefly, an intron is lost on an edge of length t with probability  where λ and μ are the gain and loss rates; a new intron appears in a previously unoccupied site with probability

where λ and μ are the gain and loss rates; a new intron appears in a previously unoccupied site with probability  . The constant rate model (Csűrös et al., 2007) is completely specified by the branch-specific gain/loss rates, and the probability with which intron sites are occupied at the root. The rate variation model (Csűrös et al., 2008) assumes that intron sites belong to discrete rate categories. Each site category is defined by a pair of loss and gain rate factors (α,β), so that the loss rates μα and gain rates λβ apply on each edge with prototypical rates μ and λ. Malin optimizes rate factors, and can analyze the same dataset with different models simultaneously.

. The constant rate model (Csűrös et al., 2007) is completely specified by the branch-specific gain/loss rates, and the probability with which intron sites are occupied at the root. The rate variation model (Csűrös et al., 2008) assumes that intron sites belong to discrete rate categories. Each site category is defined by a pair of loss and gain rate factors (α,β), so that the loss rates μα and gain rates λβ apply on each edge with prototypical rates μ and λ. Malin optimizes rate factors, and can analyze the same dataset with different models simultaneously.

Malin is written entirely in Java. It can be used on any computer platform with a Java Runtime Environment (implementing J2SE 1.5 or higher), including Microsoft Windows, MacOS X and Linux. In addition, Malin is also available as an integrated application on MacOS X. The software is distributed with test data and a detailed User's Guide. Input files follow commonly used formats: Newick format for the possibly multifurcating species phylogeny, Fasta format for alignments and the syntax used by Rogozin et al. (2003) for intron tables. Intron sites are specified in Fasta headers. Analysis results can be exported into tab-delimited text files.

The software implements previously described computational innovations (Csűrös et al., 2007, 2008), including rate optimization, posterior predictions, fast evaluation of the likelihood function and estimation of statistical confidence through bootstrapping. Malin provides a feature-rich graphical user interface for the analysis tasks. Figure 1 gives an example of an alignment panel, where, in order to build an intron table, the user selects the conservation criteria (such as the minimum number of gapless positions next to an intron site) for discerning homologous sites in a set of multiple alignments.

Ideally, Malin will enable researchers to conduct phylogenetic gene structure analysis with the same ease that is currently available for molecular sequences.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to Péter Csűrös for help with the software integration in Microsoft Windows. I am greatly indebted to Liran Carmel, Eugene Koonin, Jacek Majewski, Igor Rogozin and Scott Roy for helpful advice and discussions about intron evolution.

Funding: This research project has been supported by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Carmel L, et al. An expectation-maximization algorithm for analysis of evolution of exon-intron structure of eukaryotic genes. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2005;3678:35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Carmel L, et al. Three distinct modes of intron dynamics in the evolution of eukaryotes. Genome Res. 2007;17:1034–1044. doi: 10.1101/gr.6438607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L, Penny D. Complex spliceosomal organization ancestral to extant eukaryotes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:1053–1066. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csűrös M. Likely scenarios of intron evolution. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2005;3678:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Csűrös M, et al. In search of lost introns. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:i87–i96. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csűrös M, et al. Extremely intron-rich genes in the alveolate ancestors inferred with a flexible maximum likelihood approach. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008;25:903–911. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris JS. Phylogenetic analysis under Dollo's law. Syst. Zool. 1977;26:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HD, et al. New maximum likelihood estimators for eukaryotic intron evolution. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2005;1:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen CB, et al. Patterns of intron gain and loss in fungi. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Trelles F, et al. Origins and evolution of spliceosomal introns. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2006;40:47–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogozin IB, et al. Remarkable interkingdom conservation of intron positions and massive, lineage-specific intron loss and gain in eukaryotic evolution. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1512–1517. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00558-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogozin IB, et al. Analysis of evolution of exon-intron structure of eukaryotic genes. Brief. Bioinform. 2005;6:118–134. doi: 10.1093/bib/6.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SW, Gilbert W. Rates of intron loss and gain: implications for early eukaryotic evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:5773–5778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500383102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SW, Gilbert W. The evolution of spliceosomal introns: patterns, puzzles and progress. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:211–221. doi: 10.1038/nrg1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SW, Hartl DL. Very little intron loss/gain in plasmodium: intron loss/gain mutation rates and intron number. Genome Res. 2006;16:750–756. doi: 10.1101/gr.4845406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SW, Penny D. Large-scale intron conservation and order-of-magnitude variation in intron loss/gain rates in apicomplexan evolution. Genome Res. 2006;16:1270–1275. doi: 10.1101/gr.5410606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stajich JE, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of fungal genomes reveals intron-rich ancestors. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R223. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan JC, et al. A high percentage of introns in human genes were present early in animal evolution: evidence from the basal metazoan Nematostella vectensis. Genome Inform. 2006;17:217–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]