Abstract

Study Design

Retrospective descriptive analysis

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to report the functional ability of children with spinal cord injury (SCI) as recorded on motor items of the functional independence measure (FIM) and to examine factors associated with FIM motor admission and post-discharge gain scores.

Setting

USA

Methods

Scores on FIM motor items were analyzed from 941 children (age range: 0–21; mean: 13 years 4 months; standard deviation: 4 years 8 months) admitted in acute to chronic time periods post-SCI to Shriners Hospitals for Children, USA. FIM motor scores at admission and gains at discharge were examined along with neurological level, completeness of injury, age, etiology of injury, and length of time between injury and admission and admission and discharge.

Results

FIM motor scores at admission were negatively correlated with age, neurological level, and completeness of injury. Gain in FIM motor scores was significant across neurological levels, and was associated with lower admission FIM motor scores, lower neurological level, incomplete injury, traumatic injury, and less time between injury and admission.

Conclusion

The motor function of children after pediatric SCI depends on neurological level and completeness of injury, among other factors. FIM motor scores can improve with intervention even years after the injury.

Keywords: spinal cord injury, Functional Independence Measure, motor assessment, pediatric

Introduction

A conservative 5% of the spinal cord injuries (SCI) reported each year in North America occur in individuals younger than 15 years of age and about 20% occur in those younger than 20 years of age.1–4 Life expectancy for children and adolescents with SCI is somewhat less than the general population, and is a function of neurological level and severity.5, 6 Younger children have some natural protection against injury in the compliance of the bones and ligaments surrounding the spinal cord, but once these structures are breached, the resultant SCI tends to be severe.7 Despite the frequency, duration, and extent of disability following pediatric SCI, expectation of motor function post-injury has largely relied on data from adults, not children.

One notable exception is Garcia, et al.,8 who reported the functional status of 91 children with SCI based on the Functional Independence Measure (FIM)9 or Pediatric FIM (WeeFIM)10 scored upon admission and discharge at a rehabilitation hospital. FIM scores were correlated with neurological level11 and severity or completeness of injury11 but not etiology and age in this sample of children in an initial acute phase post-SCI.

The purpose of this study is to report the motor function of children with SCI. Because paralysis is the major contributor to disability in this population, we examined only the 13 motor items of the FIM (which are identical to the motor items of the WeeFIM) along with the relationship between FIM motor scores, neurological levels, severity and time factors. Our questions were:

What is the functional ability of children post-SCI as indicated by FIM motor scores at admission and discharge?

Can children post-SCI show improvements in FIM motor scores?

What relationship do FIM motor scores post-pediatric SCI have with factors like neurological level, completeness of injury, age, etiology, and time since injury?

What multivariate relationships do FIM gains have with neurological level, completeness of injury, age, etiology, time since injury, and time since admission?

Materials and Methods

Data were collected between 1983 and 2007 at the three Shriners Hospitals for Children (SHC) (Philadelphia, Chicago, and Northern California) that have designated SCI centers. These data were part of a longitudinal pediatric SCI registry. Each hospital obtained approval for the registry from their respective Institutional Review Board or Research Ethics Committee. Parents and children provided written informed consent and assent, respectively. The FIM was administered according to a standard protocol by trained health care professionals to children of all ages at initial admission to the SHC system, at discharge from the initial inpatient stay, and again at the time of follow-up. Admission to SHC for some children was soon after the injury; for other children, admission to SHC occurred years later, for purposes such as surgical and other interventions to improve function and comfort. No data were analyzed for more than one admission of any child. Over 6,500 FIM assessments were collected on 1750 children with SCI. In addition, neurological level,11 completeness of injury using the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale (AIS) designations, etiology of injury, and age at time of injury were collected. Among the children enrolled in the SCI registry, 941 had complete scores for the FIM motor items for admission; 628 of these had complete scores for the FIM motor items at a discharge assessment recorded at least 3 days after admission. We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

FIM items are scored “1-unable” to “7-independent.” Although FIM scores are on an ordinal scale, scores were treated as interval data for these analyses, as in Garcia, et al.,8 using only those FIM assessments for which there were no missing data for any motor items. Possible scores ranged from 13 to 91. For research question 1, we recorded FIM motor scores at admission and discharge. For question 2, we compared admission and discharge scores as recorded for the initial inpatient stay of 3 days or more, using paired t-tests, and calculated FIM gain. For question 3, we examined the correlation between FIM motor scores and multiple factors. Neurological levels were categorized as high cervical (C2-C4), low cervical (C5-C8), thoracic, and lumbo-sacral. Severity was categorized as motor complete (AIS A, B) and incomplete (AIS C, D). Injuries designated AIS E (essentially normal motor testing) were included in the incomplete category because AIS E indicated an initial spinal cord injury with sacral sparing, that clinicians still designated as such at re-evaluation. Etiology was categorized as traumatic (sports and recreation, vehicular, falls or flying objects, and violent causes) and non-traumatic (medical or surgical etiologies). For question 4, we used regression to examine the multivariate relationship between FIM gain and neurological level, completeness of injury, age, etiology, time since injury, and time between admission and discharge. Spearman rank order correlation was used to examine associations between FIM motor scores and categories of neurological levels. Pearson correlation was used to examine all other bivariate associations. All analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (2003) and SPSS statistical package version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

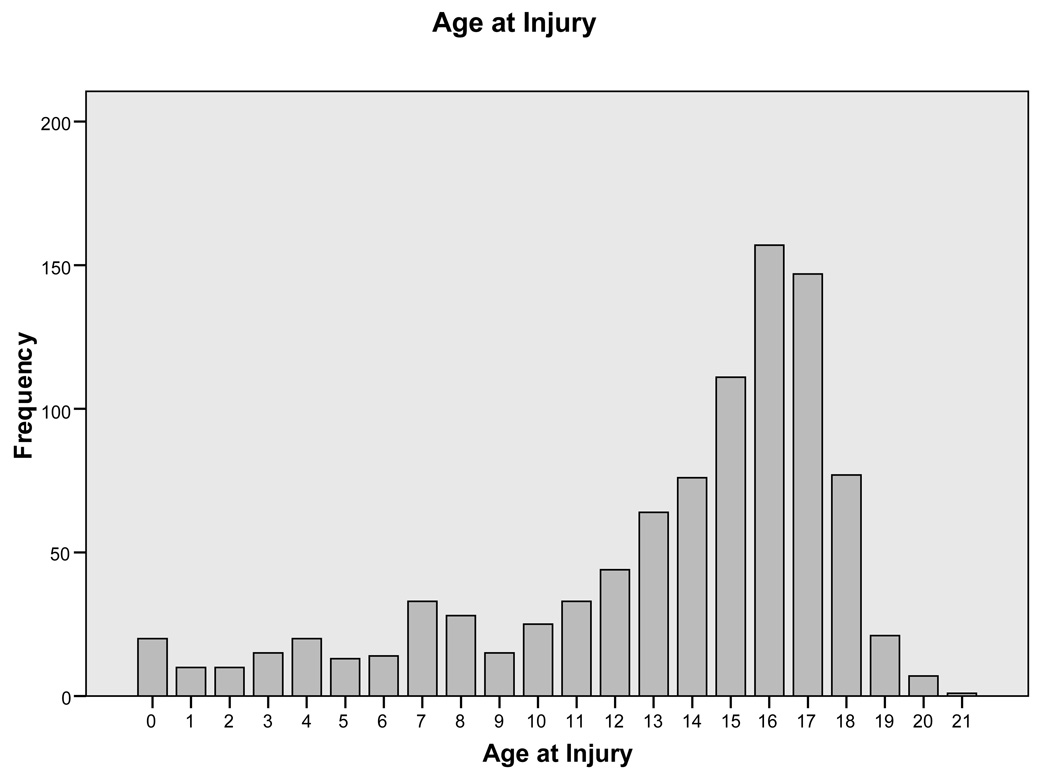

For the 941 children with complete admission FIM motor items, age at the time of injury ranged from 0 to 21 years (mean = 13 years 4 months, standard deviation = 4 years 8 months) with 56.4% aged 15 and under (Figure 1). Data from individuals aged 18–21 were retained in these analyses because the tradition at SHC and many other pediatric facilities has been to provide care through the age of 21. Although specific data were not collected regarding the home state or socio-economic level of these individuals, the three SHC hospitals draw from every state in the United States of America, and from families of which approximately 20% have no medical insurance coverage.

Figure 1.

Frequency of Various Ages at Time of Spinal Cord Injury in this Sample (N = 941)

Table 1 shows the number and proportion of injuries at the various neurological levels, at the designated completeness, and with the designated etiology. The average number of days between injury and admission was 522 (SD=872 days), with 30% of admissions to the SHC system in the first 2 months post-injury, and 47% of admissions in the first 6 months. Out of the 941 children with complete FIM motor items at admission, 33% were discharged in under 3 days. For the 628 children who had inpatient stays of 3 days or more, the average number of days between admission and discharge was 60 (SD=66 days), with 40% discharged within 1 month of admission, and 65% discharged within 2 months. The average inpatient stay was 64 days (SD=61) for the high cervical group, 83 days (SD=89) for the low cervical group, 46 days (SD=44) for the thoracic group, and 39 days (SD=28) for the lumbosacral group.

Table 1.

Number and Proportions of Children with Injuries with the Designated Neurological Level, Completeness*, and Etiology

| Neurological Level | Completeness of Injury | Etiology | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | N | % | Completeness | N | % | Etiology | N | % |

| High Cervical (C2 to C4) | 114 | 12.1 | AIS A | 619 | 65.7 | Fall/flying object | 55 | 5.8 |

| Low Cervical (C5 to C8) | 272 | 28.9 | AIS B | 113 | 12.0 | Medical/surgical | 115 | 12.2 |

| Thoracic | 414 | 44.0 | AIS C | 79 | 8.4 | Sport/Recreation | 177 | 18.8 |

| Lumbo-sacral | 86 | 9.1 | AIS D | 111 | 11.8 | Vehicular | 454 | 48.2 |

| Undetermined | 55 | 5.8 | AIS E | 3 | 0.3 | Violence | 111 | 11.8 |

| Undetermined | 16 | 1.6 | Other | 26 | 2.8 | |||

| Unknown | 3 | 0.2 | ||||||

| Total | 941 | 100 | Total | 941 | 100 | Total | 941 | 100 |

AIS = American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale

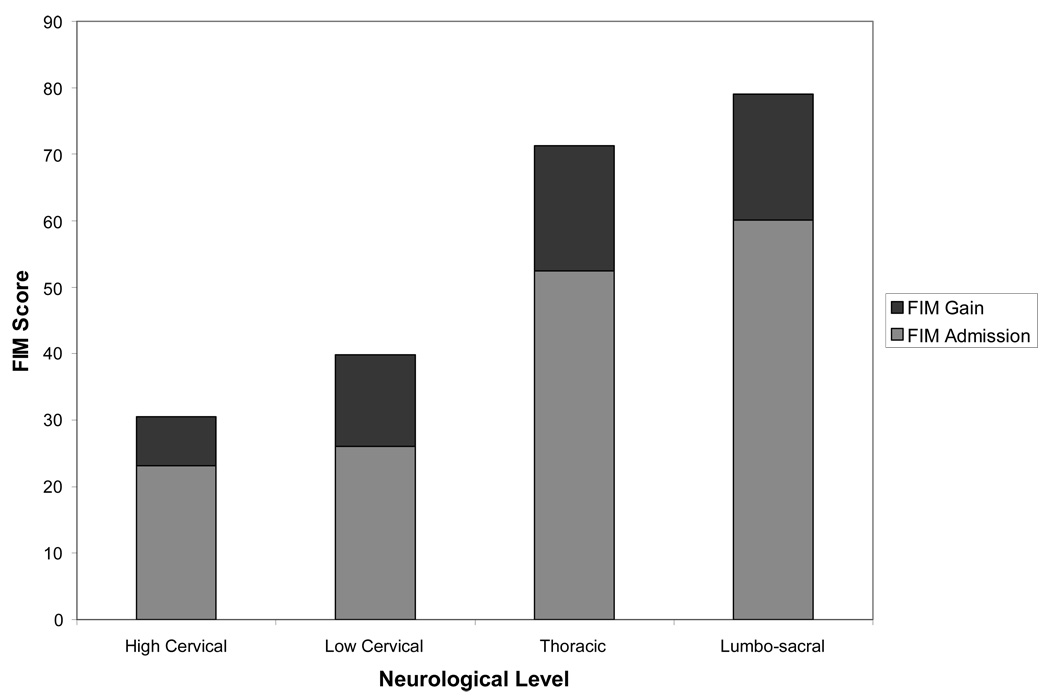

The overall mean for the motor FIM scores at admission was 46.4 (SD=26.0). For the 628 children who also had discharge assessment data 3 or more days after admission, the mean at admission was 39.2 (SD=23.9), and the mean at discharge was 55.1 (SD=24.6). Figure 2 depicts the average FIM motor scores for children in each group of neurological levels: high and low cervical, thoracic, and lumbosacral injuries.

Figure 2.

Average Functional Independence Measure (FIM) Motor Scores at Admission Plus Average Gain at Discharge for Various Neurological Levels for Those with Initial Inpatient Stays of 3 Days or More (N = 628)

The gain from admission to discharge was significantly different from zero across all levels (t = 22.84, degrees of freedom = 627, p < .00001) and for each group of neurological levels (p < .00001). About 27% of the children had no change or a decrease in recorded FIM scores from admission to discharge. About 44% gained 13 or more points in scores on FIM motor items at discharge compared to admission.

Having a motor complete SCI was significantly correlated with lower admission and discharge scores (r = −.14 and −.29 for admission and discharge, respectively, p < .001) and lower FIM gain (r = −.22, p < .001). Having a higher neurological level (fewer levels functioning normally) was significantly associated with lower admission and discharge scores (Spearman’s rho = .58 and .69 respectively, p < .001) and lower FIM gain (Spearman’s rho = .19, p < .001) (see Figure 2). There was no change in neurological level or completeness recorded between admission and discharge assessments.

FIM admission scores were negatively correlated with age at injury in the whole group (r = −.16) and specifically in those aged 15 or under (r = −.15), meaning that older children had significantly lower recorded scores on motor items (p < .001). FIM gains from admission to discharge had small positive associations with age at injury in univariate analysis, with the whole group at r = .09 (p = .03) and those 15 or younger at r = .14 (p = .01).

Traumatic etiologies were associated with lower FIM admission scores on motor items (r = −.17, p < .001) than non-traumatic etiologies were. Traumatic etiology was not associated with FIM gain in univariate analysis.

In univariate analyses, FIM gain was positively correlated with the length of time between admission and discharge (r = .14, p < .002) and negatively correlated with the length of time between the date of injury and admission to service (r = −.30, p < .001). FIM gain was negatively correlated with FIM admission score at r = −.32 (p < .001), indicating that children tended to make greater gains if they started with a lower score. FIM motor score at admission was positively correlated with the length of time between the date of injury and admission to service (r = .28, p < .001), meaning that, as time increased post-injury, children in this sample had better functional ability.

Regression using FIM gain as the outcome variable showed that FIM admission score, time between injury and admission to service, neurological level and AIS, and traumatic etiology but not age, contributed to the explanation of about 43% of the variability in FIM gain (Table 2). Of these variables, FIM admission score and the neurological level had the strongest effects on FIM gain.

Table 2.

Regression Table for Factors Contributing to Functional Independence Measure (FIM) Gains During Inpatient Stays After Pediatric Spinal Cord Injury

| Independent Variable | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | 7.785 | 3.792 | 2.053 | .040 | |

| Age at Injury | .102 | .178 | .021 | .571 | .568 |

| Number of days from injury to admission | −.003 | .001 | −.108 | −2.837 | .005 |

| Number of days from admission to discharge | .016 | .009 | .061 | 1.857 | .064 |

| FIM total at admission | −.434 | .030 | −.603 | −14.719 | .000 |

| Traumatic and medical/surgical differentiation | 4.692 | 1.892 | .083 | 2.481 | .013 |

| Motor complete vs. incomplete | −13.105 | 1.454 | −.297 | −9.011 | .000 |

| Neurological level into 4 categories | 12.181 | .809 | .571 | 15.063 | .000 |

Dependent Variable: FIM gain

Discussion

This study documents the average functional abilities of children in acute through chronic phases post-SCI. Functional ability was associated with neurological level and completeness, and showed improvements even years post-injury. Weak but significant associations were noted in simple correlations between FIM motor scores and age, traumatic versus non-traumatic injury, and time since injury. The negative correlation of FIM motor scores with age was unexpected, because older children should normally show more independent motor function, but confounding with other time-related factors may have affected these results. In multivariate analysis, FIM gain was not associated with age at injury, but only with time since injury, neurological level, completeness, functional ability at admission, and etiology. No data were provided regarding the interventions for these children, so FIM gain could not be associated with particular treatments.

These admission FIM scores reflected functional status upon first inpatient encounter with SHC, not initial rehabilitation post-SCI. Children were admitted for a variety of reasons, including reconstructive surgeries for the upper limb, brush-up rehabilitation, and habilitation, or the teaching of new skills to children who had not yet developed far enough to attain such skills prior to injury.12 Even if some of the gains recorded were because of some lack in the adequacy of initial rehabilitation post-SCI, finding improvement in over two-thirds of the subjects may indicate that children with SCI have the potential to make gains even years after injury, and the FIM can record that improvement.

In this study, 27% of the children showed either no gain or a loss at discharge. Stable or decreased FIM scores could have been due to temporary post-operative precautions for children following upper extremity reconstruction,13, 14 spine surgery for correction of neuromuscular scoliosis,15 or hip surgery.16 Analysis of follow-up FIM assessments one year after these inpatient stays may show improvement. Future studies of the results of specific interventions may help to answer questions about gain or lack thereof in specific skills.

Another explanation for the lack of gain might be ceiling effects in the FIM motor domain. In a study of adults with SCI, Hall, et al.,17 reported no ceiling effect in motor items, although most subjects scored at the ceiling of the cognitive and social domains. Only 12 children in the current study had the maximum score of 91 at admission, thus any ceiling effect on average was minimal.

The factors associated with FIM gains noted here contrast somewhat with those identified from previous studies, perhaps because this study population includes a range of acuity post-SCI. Finding no age effect in the multivariate analysis counters Wang, et al.,18 who reported greater improvement with younger ages in 30 children with acute spinal cord injuries. Finding higher average FIM gains associated with injury at lower neurological levels counters Garcia, et al.,8 who reported a trend for children with injuries at the C6 to T1 levels at the acute to sub-acute stages to have the greatest gains. Similar to the trends reported by Garcia, et al.,8 however, incomplete motor injuries and traumatic etiologies were associated with higher FIM gains in our multivariate analysis.

This study’s FIM scores compare favorably to FIM scores reported in studies of adults with SCI (age 16 or over at injury). At the high cervical neurological level (C4 and above), the admission and discharge scores averaged 23 and 30, respectively, in this study. Hall, et al.,17 reported that for adults with a C4 SCI, discharge and 1 year FIM motor scores average 23 and 27. Discharge scores for children with thoracic and lumbosacral injuries averaged 71 and 79, respectively, compared to 69 and 73 for those with the same level injuries in adults.17 The adults made greater gains than the children in this study during inpatient stays, but were uniformly admitted within 60 days (mean = 8 days, SD=13 days) of injury so were more acute. The average gains for adults after one year post-injury were limited to 5 points at best.17

In this study, 66% of the children had a complete injury, designated AIS A. There is no other database specifically devoted to pediatric SCI with which to compare this study population, but this proportion contrasts with the 50% of adults and children with a complete injury described by Go, et al..19 The higher proportion of complete injuries in children may reflect the tendency for pediatric SCI to result in more severe deficits.7 Misclassification of completeness of injury may also occur20: children injured prior to being toilet trained may have difficulty with the anal exam used to determine S4/S5 functioning.

Limitations to this study include the lack of specific information about the type of intervention provided to these children between admission and discharge. However, children with SCI commonly require interventions related to their growth and development.12 Because this study focused on scores of FIM motor items rather than including the cognitive and social items, the score averages do not compare directly to some in other studies reporting total FIM scores.8

The proportions of cases having a particular neurological level or specific etiology provided in this study do not necessarily reflect the proportions in the whole population of children with SCI. These proportions only reflect the population having admission and discharge assessments at these three sites of the SHC. Annual follow-up data were not examined for this study, but might show differences in FIM gains compared to those reported here.

This study provides some initial description of motor function in a fairly large and diverse group of children with SCI. Although this makes a good basis for comparison for clinicians and researchers interested in the expected functional outcomes post-pediatric SCI, specific intervention studies, possibly with specific instruments to focus on changes in particular skills, are needed. Future projects might examine the gains in motor function over longer post-inpatient follow-up periods, gains in particular dimensions of motor function like self-care and transfers, and greater specificity regarding which age groups show gains over what time periods. FIM motor scores might also be examined for ceiling, floor, or content gaps in subsets of the population that affect the ability of researchers to make a reasonable prognosis for children who have SCI.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship: Shriners Hospitals for Children, USA, Grant #9146; Independent Scientist Award (K02 HD45354-01) to Dr. Haley; Post-doctoral Fellowship, NIDRR grant #H133P0001 with the Health and Disability Research Institute, School of Public Health, Boston University, to Dr. Allen.

References

- 1.Hamilton MG, Myles ST. Pediatric spinal injury: review of 174 hospital admissions. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:700–704. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.77.5.0700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nobunaga AI, Go BK, Karunas RB. Recent demographic and injury trends in people served by the Model Spinal Cord Injury Care Systems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:1372–1382. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeVivo MJ, Vogel LC. Epidemiology of spinal cord injury in children and adolescents. J Spinal Cord Med. 2004;27(S-1):S4–S10. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2004.11753778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson AB, Dijkers M, DeVivo MJ, Poczatek RB. A demographic profile of new traumatic spinal cord injuries: change and stability over 30 years. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1740–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogel LC, DeVivo MJ. Etiology and demographics. In: Betz RR, Mulcahey MJ, editors. The Child with a Spinal Cord Injury. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1996. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogel LC, DeVivo MJ. Pediatric spinal cord injury issues: etiology, demographics, and pathophysiology. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 1997;3:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Proctor MR. Spinal cord injury. Crit Care Med. 2002;30 Suppl:S489–S499. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200211001-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia RA, Gaebler-Spira D, Sisung C, Heinemann AW. Functional improvement after pediatric spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81(6):458–463. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200206000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton BB, Granger CV, Sherwin FS, Zielezny M, Tashman JS. Fisher ZM. Rehabilitation Outcomes Analysis and Measurement. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Company Inc; 1987. A uniform national data system for medical rehabilitation; pp. 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Msall ME, DiGaudio K, Rogers B, et al. The Functional Independence Measure for Children (WeeFIM). Conceptual Basis andf Pilot Use in Children with Developmental Disabilities. Clin Pediatr. 1994 July;:421–430. doi: 10.1177/000992289403300708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marino RJ, Barros T, Biering-Sorensen F, Burns SP, Donovan WH, Graves DE, Haak M, Hudson LM, Priebe MM. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2003;26 suppl.1:S50–S56. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2003.11754575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulcahey MJ, Betz RR. Considerations in the rehabilitation of children with spinal cord injuries. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 1997;3(2):31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulcahey MJ, Lutz C, Kozin S, Betz RR. Prospective evaluation of biceps to triceps and deltoid to triceps for elbow extension in tetraplegia. J Hand Surg [Am] 2003;28A:964–971. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(03)00485-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulcahey MJ. Rehabilitation and outcomes of tendon transfers. In: Betz RR, Mulcahey MJ, editors. The Child with Spinal Cord Injury. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; 1996. pp. 419–448. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta S, Betz RR, Mulcahey MJ, McDonald C, Vogel LC, Anderson C. Effect of bracing on paralytic scoliosis secondary to spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2004;27 Supplement 1:S88–S92. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2004.11753448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rink P, Miller F. Hip instability in SCI patients. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10:583–587. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199009000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall KM, Cohen ME, Wright J, Call M, Werner P. Characteristics of the Functional Independence Measure in traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:1471–1476. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang MY, Hoh DJ, Leary SP, Griffith P, McComb JG. High rates of neurological improvement following severe traumatic pediatric spinal cord injury. Spine. 2004;29:1493–1497. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000129026.03194.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Go BK, DeVivo MJ, Richards JS. The epidemiology of spinal cord injury. Chapter 3. In: Stover SL, DeLisa JA, Whiteneck GG, editors. Spinal Cord Injury: Clinical Outcomes from the Model Systems. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulcahey MJ, Gaughan J, Betz RR, Johanson K. The international standards for neurological classification of SCI: reliability of data when applied to children and youth. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:452–459. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]