Abstract

BACKGROUND

A growing body of evidence suggests that long-term survivors with one of the more common forms of adult cancer report similar quality of life (QOL) to the general population. However, specific concerns have been identified (sexual dysfunction, fatigue, distress) in this population. Also, less is known about survivors of adult non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), a disease often marked by alternating periods of disease and remission. Therefore, this study compares the QOL status of individuals who report having active NHL with those who are disease-free short-term (2–4 years post-diagnosis; STS) and long-term (≥5 years post-diagnosis; LTS) survivors.

METHODS

Eligible survivors completed a mailed survey with validated measures: physical and mental health status, SF-36; cancer-related QOL, FACT-LYM; and self-reported impact of cancer, IOC. Other data were collected to examine as correlates.

RESULTS

Seven-hundred and sixty one survivors identified from two NC cancer registries participated. Subjects averaged 10.4 (range, 2–44) years post-diagnosis and 62.7 (range, 25–92) years of age. Survivors with active disease (n=109) demonstrated worse physical and mental health functioning, QOL, and less positive and more negative impacts of cancer when compared to disease-free survivors (n=652; all P≤.01). No significant differences were found between STS and LTS.

CONCLUSIONS

While NHL patients with active disease reported more negative outcomes when compared to off-treatment survivors, length of time since diagnosis did not appear to matter with regard to outcomes for STS and LTS. In addition, mixed results from comparisons to general population norms suggest the need for supportive care for this diverse survivorship group.

Keywords: Quality of life, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, post-traumatic stress, FACT-G, FACT-LYM, SF-36, IOC

INTRODUCTION

A growing body of evidence suggests that long-term survivors who were diagnosed and treated for one of the more common forms of adult cancer report quality of life (QOL) similar to that of the general population.1–4 However, specific areas of unresolved concern have been identified in this population, including sexual dysfunction,3,5,6 low energy level and fatigue,1,7,8 and post-traumatic stress (PTS).9–12 Further, several studies have demonstrated positive outcomes associated with having cancer, such as greater appreciation for life, closer personal relationships, and deeper spiritual understanding (post-traumatic growth).6

Less is known about the health status and QOL specific to survivors of adult non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), the sixth most common cancer in the US. NHL is a heterogeneous group of cancers of the lymphatic system with an overall 5-year survival rate of 50–60% (statistics vary depending on the cell type, stage of disease at diagnosis, and treatment). Indolent lymphomas generally carry a good prognosis with a median survival of 10 years but a high rate of relapse, and are usually not curable in advanced stages. Treatment for the indolent forms includes periods of watchful waiting, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. By comparison, 30–60% of individuals who convert to or present with aggressive forms of NHL can be cured with intensive chemotherapy regimens, but the disease has a shorter natural history, with the greatest risk of relapse within 2 years of treatment cessation.13 Thus, from a patient perspective, various forms of NHL are experienced as a life-long chronic illness, with intermittent symptom-free and symptom exacerbation phases requiring treatments.

Given the expected increase in NHL incidence rates14 attributed to the increasing average age of the US population, the time has come to understand the health and QOL status and needs of this population overall, and by survivorship status. Such information may suggest areas for treatment or the targeting of scarce health care resources. Thus, this paper used three outcome measures to compare the health and QOL status of those who report active NHL disease with those who are short-term survivors (STS; 2–4 years post-diagnosis) and long-term survivors (LTS; ≥5 years post-diagnosis) who report being in remission or cured.

Conceptual model

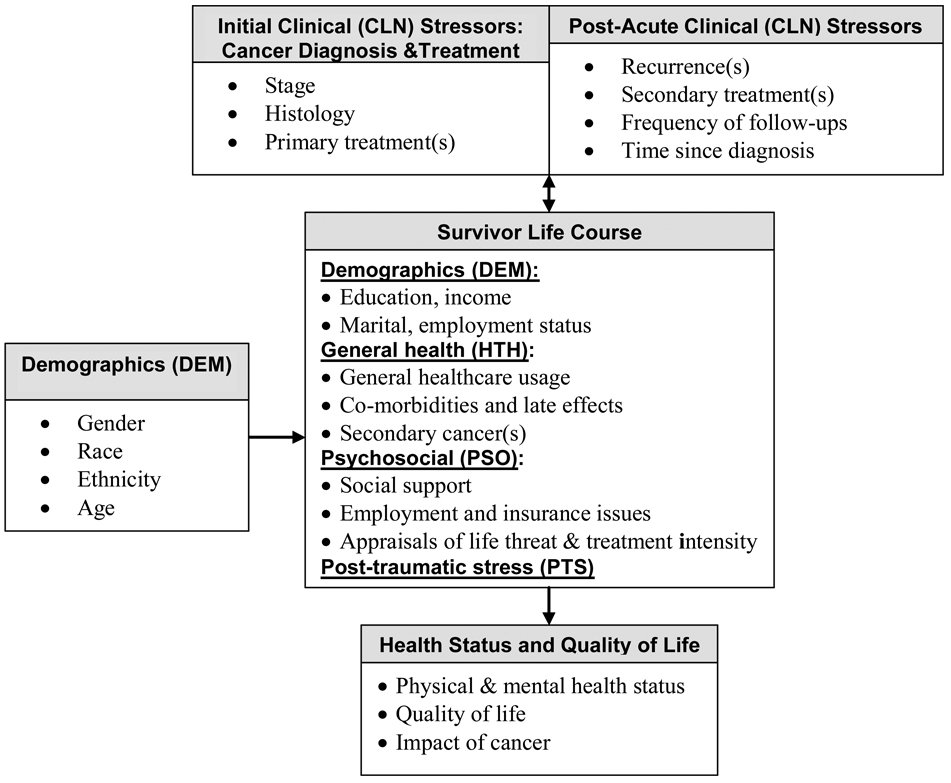

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model underlying this research which is based on coping theories15 and empirical research.3,9,12,16–18 Clinical characteristics are conceptualized as stressors, while survivor life-course factors are comprised of selective demographic, health and psychosocial characteristics that may influence each other and the outcome of these stressors. For example, quality of social support can affect an individual’s appraisal of cancer’s impact on his/her life,18 which may either diminish or enhance individual coping strategies and possibly lead to negative and/or positive QOL-related outcomes. Also, individuals with active disease may be more likely to experience higher levels of clinical stress than those who are in remission or cured.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Cancer Survivorship

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Potential study participants were identified through the Duke and University of North Carolina Tumor Registries and contacted by mail following Institutional Review Board and physician approvals. NHL patients were eligible if they were at least 19 years old and 2 years post-diagnosis.

Measures

Health Status and QOL Outcomes

Three measures were used to assess outcomes. One, the SF-36, a general health measure of physical and mental health functioning, was used to allow for comparisons to general population-based norms. It is comprised of 36 items representing eight sub-scales and two summary scores, the physical component (PCS) and the mental component (MCS).19 For purposes of comparison, a score of 50 (SD=10.0) represents the population mean.20 Reliability estimates ranged from α=.84-.95. Second, to capture cancer-specific QOL, the 27-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-G) and 15-item FACT-LYM module (lists lymphoma-related symptoms such as fevers, night sweats, itching) were used.21 The FACT-G was originally intended for patients in treatment, but is increasingly being used with off-treatment samples. Reliability statistics for both ranged from α=.77–.93. Third, the Impact of Cancer (IOC) assessed respondents’ perceptions of positive and negative impacts of cancer in various aspects of their lives, using 5 positive and 5 negative subscales and two summary scores (Positive and Negative Impact).18 The IOC was developed to assess certain aspects of survivorship not measured by other QOL measures (e.g., health worries, meaning of cancer, post-traumatic growth).22 Reliability estimates ranged from α=.62–.91. Higher scores on all of the outcome measures indicate better health status and QOL, except for the IOC Negative Impact, where higher scores indicate greater negative impacts.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Demographic (DEM; gender, race, ethnicity, age, income, education, marital status, employment status) and clinical (CLN; histology, stage, surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, bone marrow/stem cell transplant, biologic therapy, NHL treatment status, recurrence, number of oncology-related visits, site of treatment) information was collected via self-report and the Tumor Registry databases. NHL histology was categorized as indolent or aggressive based on the updated REAL/WHO classification system.23

General Health (HTH)

The Self-administered Co-morbidity Questionnaire (SCQ)24 was used to assess non-NHL health problems. In addition, selected questions related to healthcare usage were adapted for use from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study survey.25

Psychosocial (PSO)

The 20-item Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey measured perceived availability of social support26 (range 20–100; α=.97). The Appraisal of Life Threat and Treatment Intensity Questionnaire (six items, range 6–30; α=.80) assessed the extent to which cancer and its treatment are perceived to be life-threatening and intense.27 Employment and insurance-related situations and difficulties were collected using 24 questions (possible range 0–24, α=.82) derived from a Cancer and Leukemia Group B research instrument.28

Post-traumatic stress (PTS)

The Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Checklist (PCL-C) assesses symptomatology in non-combat populations by presenting a symptom checklist that closely mirrors DSM-IV criteria for a formal diagnosis of PTSD.29, 30 The instructions were modified for the current study, such that survivors were asked to rate each symptom in the past 4 weeks with respect to their diagnosis and treatment for lymphoma. The continuous scoring method was used and Cronbach’s α ranged from .78-.91.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were used to estimate the health status and QOL means for this population overall and by survivorship status (active disease, STS, LTS). Chi-square and ANOVA were used to compare distributions and mean scores on outcome variables and the covariates across the three survivor groups. The amount of missing data in income (10%) and stage (12%) variables justified multiple imputation via the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC);31 imputed values for disease status and outcome variables were not generated.

Twenty datasets containing imputed values were used in the multiple linear regression analyses via the SAS MIANALYZE procedure.32 Multiple linear regressions were conducted to examine the association between survivorship status and outcomes, adjusting for covariates. For all comparisons, individuals with active disease were the reference group. For each of the five outcome summary scores (PCS, MCS, FACT-G, IOC Positive, IOC Negative), six sequential series of linear regression models were constructed to examine the association with active disease such that each domain of covariates was added in order of strength of association with the outcomes (correlations with DEM and CLN were small; HTH were medium; and PSO and PTS were large). That is, the first model tested for the relationship between active disease and disease-free status with summary scores without accounting for covariates; then, subsequent models added DEM, CLN, HTH, PSO and PTS. The order of entry had no bearing on the final results for each measure. Statistical analyses, including tests for multi-collinearity, were carried out using SAS 9.1 software.

RESULTS

Seven hundred and sixty-one participants (74% response rate) provided informed consent. Table 1 lists the information collected by total sample and survivorship status. Sample bias analyses using demographic information from the registries indicated that participating survivors were less frequently non-Caucasian and older at diagnosis and study enrollment than non-participants (all P<.001). Survivors who reported having active disease were more likely to have been diagnosed with an indolent lymphoma, received biologic therapy, had more recurrences, types of treatment, and PTS than disease-free survivors (all P<.01). STS were younger at enrollment, less likely to have a secondary cancer, and had less co-morbidity than those with active disease or LTS (all P<.05). Although not detailed in Table 1, many reported receiving current treatment for co-morbid conditions, including high blood pressure (34%), heart disease (17%), back pain (15%), osteoarthritis (15%), and depression (13%). Fourteen percent of survivors reported a history of other non-skin cancers, including prostate, breast, melanoma, colon, and bladder.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Study Sample (n=761)

| All survivors* N= 761 |

Active disease†n=109 |

Short-term survivor╪n=150 |

Long-term survivor§ n=502 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics (DEM) | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | P-value | |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 383 | 50.3 | 54 | 49.5 | 73 | 48.7 | 256 | 51.0 | .868 | |

| Female | 378 | 49.7 | 55 | 50.5 | 77 | 51.3 | 246 | 49.0 | ||

| Race | ||||||||||

| Caucasian | 659 | 86.6 | 88 | 80.7 | 133 | 88.7 | 438 | 87.3 | .103 | |

| African-American | 67 | 8.8 | 15 | 13.8 | 10 | 6.7 | 42 | 8.4 | ||

| Multiple race | 27 | 3.5 | 5 | 4.6 | 5 | 3.3 | 17 | 3.4 | ||

| Other | 8 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 1.3 | 5 | 0.9 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 750 | 98.6 | 107 | 98.2 | 148 | 98.7 | 495 | 98.6 | .933 | |

| Hispanic | 11 | 1.4 | 2 | 1.8 | 2 | 1.3 | 7 | 1.4 | ||

| Income level | ||||||||||

| < $30,000 | 183 | 26.7 | 28 | 28.0 | 32 | 21.3 | 123 | 27.3 | .763 | |

| $30,000 – $59,999 | 208 | 30.3 | 32 | 32.0 | 39 | 26.0 | 137 | 30.4 | ||

| $60,000 – $89,999 | 126 | 18.4 | 21 | 21.0 | 27 | 18.0 | 78 | 17.3 | ||

| ≥ $90,000 | 169 | 24.6 | 19 | 19.0 | 37 | 24.7 | 113 | 25.1 | ||

| Education | ||||||||||

| High school or less | 208 | 27.8 | 29 | 27.6 | 28 | 18.8 | 151 | 30.5 | .080 | |

| Some college or trade school | 236 | 31.6 | 31 | 27.5 | 55 | 36.9 | 150 | 30.4 | ||

| College or post-grad | 304 | 40.6 | 45 | 47.9 | 66 | 44.3 | 193 | 39.1 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Married or living together | 579 | 76.3 | 81 | 75.0 | 122 | 81.3 | 376 | 75.0 | .268 | |

| Not married or living together | 180 | 23.7 | 27 | 25.0 | 28 | 18.7 | 125 | 25.0 | ||

| Employment status | ||||||||||

| Retired or unemployed | 450 | 59.8 | 69 | 63.9 | 80 | 54.1 | 301 | 60.7 | .229 | |

| Employed | 302 | 40.2 | 39 | 36.1 | 68 | 45.9 | 195 | 39.3 | ||

| Age at enrollment: mean (SD) | 62.7 (13.4) | 62.7 (12.6) | 59.7 (14.1) | 63.6 (13.2) | .008 | |||||

| 25–49 | 135 | 17.7 | 20 | 18.3 | 36 | 24.0 | 79 | 15.7 | .282 | |

| 50–64 | 279 | 36.7 | 44 | 40.4 | 54 | 36.0 | 181 | 36.1 | ||

| 65–79 | 271 | 35.6 | 34 | 31.2 | 48 | 32.0 | 189 | 37.6 | ||

| ≥80 | 76 | 10.0 | 11 | 10.1 | 12 | 8.0 | 53 | 10.6 | ||

| Clinical Characteristics (CLN) | ||||||||||

| NHL histology | ||||||||||

| Indolent | 361 | 50.2 | 85 | 81.0 | 57 | 40.4 | 219 | 46.3 | <.001 | |

| Aggressive | 358 | 49.8 | 20 | 19.0 | 84 | 59.6 | 254 | 53.7 | ||

| NHL stage at diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Stage I | 210 | 31.3 | 29 | 34.1 | 39 | 28.7 | 142 | 31.6 | .278 | |

| Stage II | 141 | 21.0 | 10 | 11.7 | 31 | 22.8 | 100 | 22.2 | ||

| Stage III | 131 | 19.5 | 23 | 27.1 | 26 | 19.1 | 82 | 18.2 | ||

| Stage IV | 189 | 28.2 | 23 | 27.1 | 40 | 29.4 | 126 | 28.0 | ||

| Sum of treatment types: mean (SD) | 2.1 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.3) | 2.2 (1.1) | 2.1 (1.0) | .006 | |||||

| Surgery | 226 | 30.5 | 25 | 22.9 | 44 | 30.6 | 157 | 32.0 | .235 | |

| Radiation | 364 | 47.8 | 48 | 44.0 | 61 | 40.7 | 255 | 50.8 | .064 | |

| Chemotherapy | 617 | 81.1 | 83 | 76.2 | 120 | 80.0 | 414 | 82.5 | .290 | |

| Bone marrow/stem cell transplant | 119 | 15.6 | 16 | 14.7 | 28 | 18.7 | 75 | 14.9 | .521 | |

| Biologic therapy | 215 | 28.3 | 60 | 55.1 | 59 | 39.3 | 96 | 19.1 | <.001 | |

| Current treatment status | ||||||||||

| Not in treatment | 686 | 90.9 | 38 | 35.5 | 150 | 100.0 | 502 | 100.0 | n/a | |

| Receiving treatment | 69 | 9.1 | 69 | 64.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Number of NHL recurrences | ||||||||||

| 0 | 517 | 68.6 | 51 | 47.7 | 120 | 80.5 | 346 | 69.5 | <.001 | |

| ≥1 | 237 | 31.4 | 56 | 52.3 | 29 | 19.5 | 152 | 30.5 | ||

| Age at diagnosis: mean (SD) | 52.3 (14.1) | 54.5 (13.2) | 55.9 (14.2) | 50.7 (14.0) | <.001 | |||||

| Range: | 19–87 | 20–82 | 22–87 | 19–82 | ||||||

| Years since diagnosis: mean (SD) | 10.4 (7.2) | 8.1 (5.1) | 3.8 (0.7) | 12.9 (7.3) | <.001 | |||||

| 2–4 yrs | 182 | 23.9 | 32 | 29.4 | 150 | 100.0 | ||||

| 5–9 yrs | 285 | 37.5 | 48 | 44.0 | 237 | 47.2 | ||||

| 10–14 yrs | 125 | 16.4 | 19 | 17.4 | 106 | 21.1 | ||||

| 15–19 yrs | 81 | 10.6 | 6 | 5.5 | 75 | 15.0 | ||||

| ≥20 yrs | 88 | 11.6 | 4 | 3.7 | 84 | 16.7 | ||||

| General Health (HTH) | ||||||||||

| Secondary cancer | ||||||||||

| Yes | 104 | 13.7 | 16 | 14.8 | 11 | 7.3 | 77 | 15.4 | .040 | |

| No | 655 | 86.3 | 92 | 85.2 | 139 | 92.7 | 424 | 84.6 | ||

| Co-morbidities: mean (SD) | 2.9 (2.1) | 3.0 (2.2) | 2.5 (2.1) | 3.0 (2.1) | .053 | |||||

| Psychosocial (PSO) | ||||||||||

| Social support: mean (SD) | 83.6 (15.9) | 81.7 (16.1) | 85.9 (14.2) | 83.3 (16.3) | .092 | |||||

| Range: | 26–100 | 34–100 | 36–100 | 26–100 | ||||||

| Appraisal of life threat and treatment intensity: mean (SD) | 19.4 (6.0) | 19.0 (6.5) | 19.1 (5.9) | 19.5 (5.8) | .575 | |||||

| Range: | 6–30 | 6–30 | 6–30 | 6–30 | ||||||

| Employment and insurance issues related to cancer: mean (SD) | 1.0 (2.0) | 1.2 (2.2) | 1.0 (2.0) | 1.0 (2.0) | .671 | |||||

| Range: | 0–17 | 0–12 | 0–11 | 0–17 | ||||||

| Post-traumatic Stress (PTS) | ||||||||||

| PTSD symptom clusters: mean (SD) | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.6 (0.9) | .014 | ||||||

| Range: | 0–3 | 0–3 | 0–3 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms: mean (SD) | 26.7 (9.7) | 26.2 (8.3) | 26.0 (9.3) | <.001 | ||||||

| Range: | 17–78 | 17–55 | 17–78 | |||||||

SD: standard deviation; NHL: non-Hodgkin lymphoma; P-value is for the overall comparison

Not all variables total 761 due to missing data

Active disease represents individuals who self-reported current NHL disease

Short-term survivor group represents individuals 2–4 years post-diagnosis and who reported being disease-free

Long-term survivor group represents individuals ≥5 years post-diagnosis and who reported being disease-free

Bivariate analyses

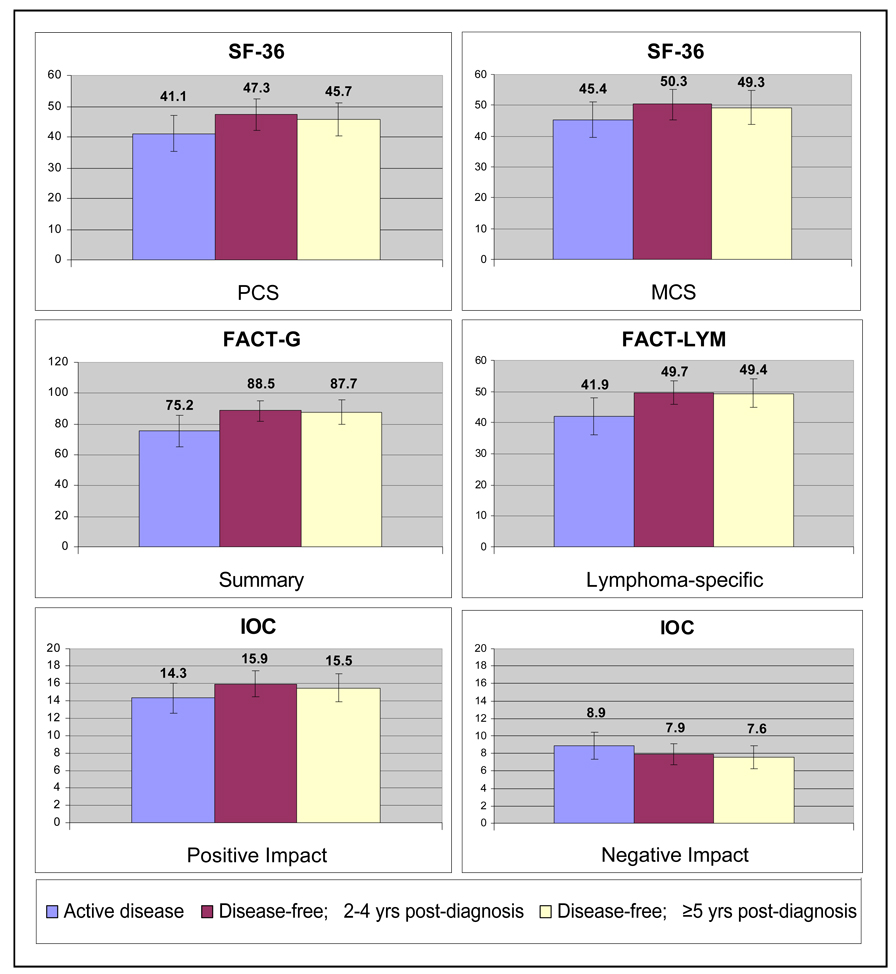

Figure 2 displays the means and standard deviations for the outcome variables by disease status. In terms of physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) health, those with active disease demonstrated worse functioning when compared to disease-free survivors (all P≤.01). Those with active disease also demonstrated significantly worse QOL as measured by the FACT-G and lymphoma-specific items than both STS and LTS (all P<.01). Also, those with active disease reported significantly less positive and more negative impact (all P<.01) via the IOC than those who were disease-free. STS and LTS did not differ significantly in any of the outcomes measured. Descriptive statistics for the outcome variables and their correlations are presented in Table 2. All outcomes were significantly related to each other with the exception of the IOC Positive Impact, which was related to the MCS (P<.05) and lymphoma symptoms (P<.001) only.

Figure 2. Health Status and Quality of Life in non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Survivors (n=761).

SF-36: Medical Outcomes Study-Short form; PCS: Physical Component Summary; MCS: Mental Component Summary; FACT-G: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; FACT-LYM: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lymphoma; IOC: Impact of Cancer

Higher scores indicate better quality of life except for the IOC Negative Impact; error bars represent 1 standard deviation from mean; comparisons between active and disease-free survivors are statistically significant (all P< .01); no statistical difference between short-term and long-term disease-free survivors (all P>.10).

TABLE 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations (n=761)

| Item | M | (SD) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SF-36 PCS | 45.4 | (11.0) | .23*** | .51*** | .52*** | −.06 | −.37*** |

| 2. SF-36 MCS | 49.0 | (11.2) | .71*** | .63*** | −.08* | −.56*** | |

| 3. FACT-G | 86.1 | (16.6) | .81*** | −.01 | −.72*** | ||

| 4. FACT-LYM symptoms | 48.4 | (9.5) | −.14*** | −.73*** | |||

| 5. IOC Positive Impact | 15.4 | (3.3) | .27*** | ||||

| 6. IOC Negative Impact | 7.8 | (2.8) |

M: Mean; SD: standard deviation; PCS: SF-36 Physical Component Summary; MCS: SF-36 Mental Component Summary; FACT-G: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General; FACT-LYM: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Lymphoma; IOC: Impact of Cancer;

P<.05;

P<.01;

P<.001.

When compared to general population-based norms (PCS and MCS; mean=50, SD=10),20 individuals with active disease scored lower in physical (mean=41.1, SD=11.9) and mental (mean=45.4, SD=11.5) health. As expected, disease-free survivors fared better, but still seemed to have worse physical health (STS, mean=47.3, SD=10.4; LTS, mean=45.7, SD=9.9) than the general adult population.20 However, after comparing our disease-free sample with their corresponding age-stratified normed groupings (25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, ≥75), our sample scored comparably (within ±1.8 points) on the PCS. Regarding mental health, scores from our disease-free survivors on the MCS (STS, mean=50.3, SD=9.9; LTS, mean=49.3, SD=11.4) were close to the general population norm;20 however, our sample scored lower (≤4.1 points) on the MCS than the corresponding age-stratified groups (except for 35–44 and ≥75), with the largest difference between the 25–34 age groups.20

Regression results

Tables 3a and 3b display the regression coefficients for the relationship between survivorship status and health status and QOL as measured by the SF-36, FACT-G and IOC. The coefficients for the series of six sequential models represent the increase in the mean level of health status and QOL related to disease-free survivorship status, after adjusting for the covariates. For example, the SF-36 Model I indicates that STS and LTS score 6.2 and 4.6 points higher respectively than those with active disease before adjusting for covariates (P<.001). While statistically non-significant, LTS reported lower health status and QOL than STS in all models.

TABLE 3.

| TABLE 3a Regression Coefficients for the Relationship between Survivorship Status (Active vs. Disease-free) and Health Status (n=761) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 Physical Component Summary (PCS) |

SF-36 Mental Component Summary (MCS) |

|||||

| Model Covariates | R2 | STS vs. Active b (Std error) | LTS vs. Active b (Std error) | R2 | STS vs. Active b (Std error) | LTS vs. Active b (Std error) |

| I. SS | .028 | 6.2 (2.0)*** | 4.6 (1.4)*** | .018 | 4.9 (2.0)*** | 4.0 (1.5)** |

| II. SS+DEM | .222 | 4.8 (1.3)*** | 4.2 (1.1)*** | .076 | 4.8 (1.4)*** | 3.7 (1.2)** |

| III. SS+DEM+CLN | .256 | 2.6 (1.9) | 0.9 (1.8) | .103 | 7.1 (2.1)*** | 5.2 (2.0)** |

| IV. SS+DEM+CLN+HTH | .447 | 1.0 (1.6) | 0.5 (1.5) | .184 | 6.1 (2.0)** | 5.0 (1.9)** |

| V. SS+DEM+CLN+HTH+PSO | .459 | 0.7 (1.6) | 0.5 (1.5) | .290 | 5.5 (1.9)** | 5.1 (1.8)** |

| VI. SS+DEM+CLN+HTH+PSO+PTS | .480 | −0.2 (1.6) | −0.7 (1.5) | .519 | 2.0 (1.6) | 1.2 (1.5) |

| TABLE 3b Regression Coefficients for the Relationship between Survivorship Status (Active vs. Disease free) and QOL (n=761) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FACT-G |

IOC Positive Impact |

IOC Negative Impact |

|||||||

| Model Covariates | R2 | STS vs. Active b (Std error) | LTS vs. Active b (Std error) | R2 | STS vs. Active b (Std error) | LTS vs. Active b (Std error) | R2 | STS vs. Active b (Std error) | LTS vs. Active b (Std error) |

| I. SS | .071 | 13.3 (4.2)*** | 12.4 (3.0)*** | .021 | 1.6 (0.2)*** | 1.2 (0.1)*** | .025 | −1.0 (0.1)** | −1.3 (0.1)*** |

| II. SS+DEM | .160 | 12.6 (2.0)*** | 11.7 (1.7)*** | .136 | 1.6 (0.4)*** | 1.3 (0.3)*** | .113 | −1.1 (0.3)** | −1.2 (0.3)*** |

| III. SS+DEM+CLN | .200 | 13.1 (2.9)*** | 10.1 (2.7)*** | .188 | 1.6 (0.6)** | 1.4 (0.5)* | .210 | −1.2 (0.5)* | −1.0 (0.4)* |

| IV. SS+DEM+CLN+HTH | .321 | 10.6 (2.7)*** | 9.2 (2.5)*** | .195 | 1.6 (0.6)** | 1.3 (0.5)* | .272 | −0.9 (0.5)* | −0.9 (0.4)* |

| V. SS+DEM+CLN+HTH+PSO | .489 | 7.9 (2.4)*** | 8.1 (2.2)*** | .315 | 1.5 (0.5)** | 1.1 (0.5)* | .422 | −0.7 (0.4) | −0.9 (0.4)* |

| VI. SS+DEM+CLN+HTH+PSO+ PTS | .677 | 3.7 (1.9)* | 2.8 (1.8) | .317 | 1.5 (0.5)** | 1.1 (0.5)* | .597 | −0.0 (0.3) | −0.1 (0.3) |

SF-36: Medical Outcomes Study-Short form; FACT-G: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; IOC: Impact of Cancer; R2: proportion of variation in the dependent variable explained by the regression equation; STS: short-term disease-free survivor (<5 years) ; LTS: long-term disease-free survivor (≥5 years); b: unstandardized regression coefficient (slope); SS: survivorship status; DEM: demographics (gender, race, ethnicity, age, income, education, marital status, employment status); CLN: clinical (histology, stage, surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, bone marrow/stem cell transplant, biologic therapy, recurrence, number of oncology-related visits, site of treatment); HTH: general health (other cancer excluding skin, co-morbidity, years since last physical exam); PSO: Psychosocial (social support, appraisal of life threat and treatment intensity, employment and insurance issues); PTS: (post-traumatic stress).

P<.05

P<.01

P<.001.

SF-36

Consistent with bivariate analyses, Model I (Table 3a) indicates that disease-free survivorship had a strong relationship to better PCS scores (P<.001). However, this relationship quickly became non-significant after accounting for the CLN covariates. In total, 48% of the variance was accounted for by all covariates. Similar to the PCS, the relationship between disease-free survivorship and the MCS was significant (P<.01). Unlike the PCS, significant differences persisted until the PTS covariate was added. A slightly higher percentage (52%) of the variance was accounted for by all covariates.

FACT-G

Consistent with the SF-36, Model I (Table 3b) indicates that disease-free survivorship had a strong relationship to better QOL scores (P<.001). The adjustment for the DEM, CLN, HTH and PSO domains reduced the magnitude of the survivorship status relationship, but in LTS remained significant until the addition of the PTS variable. A sizable amount of the variance (68%) in this cancer-specific instrument was explained by the covariates.

IOC

Consistent with the other outcome measures, disease-free survivorship had a strong relationship to better IOC Positive Impact scores (P<.001), as indicated by Model I (Table 3b). The adjustment for the CLN covariates reduced the magnitude of the survivorship status relationship, but remained significant (p<.05) through Model VI. The covariates explained only 32% of the variance.

Significant differences based on disease status also were found with the IOC Negative Impact scores. Similar to the Positive Impact scale, accounting for the CLN variables reduced the magnitude of the survivorship status relationship. However, differences between those with active disease and disease-free survivors became non-significant with the addition of the PSO variables for STS and PTS variable for LTS. This model accounted for a sizable 60% of the variance.

DISCUSSION

This study provides one of the first examinations of health status and QOL among NHL survivors. Findings included a strong independent relationship between active disease and all outcome measures. However, the relationship between survivorship status and most outcomes became non-significant upon adjustment, which indicates that differences in these measures based on active disease are essentially explained by associated differences in some of the covariates. Only one outcome measure continued to elucidate differences between those with and without active disease: the IOC Positive Impact scale. One reason for this might be that the IOC is the only QOL-related measure that contains items related to post-traumatic growth; hence, it may be a more sensitive outcome measure for individuals who are disease-free and more likely to report having benefited from their cancer experience.

Across most outcome measures there was evidence of moderation, where the inclusion of the PTS covariate produced the largest increases in R2 except for the SF-36 PCS and IOC Positive Impact models, where adding HTH and PSO covariates respectively produced the largest increases. These data suggest that survivors indicating PTS are more likely to report negative health status and QOL, as adjusting for this variable in Model VI erased the difference between active disease and disease-free scores. Also, there was evidence that HTH covariates (e.g., co-morbidity) played a pivotal role in explaining physical health status and functioning and a lesser role in overall QOL. Further, the importance of PSO variables (e.g., social support) is evident in the context of cancer-related QOL, as indicated by the largest and second-largest increase in R2 in the IOC Positive Impact and FACT-G models respectively. While the present study was not designed to determine the mechanisms linking survivorship status and health and QOL-related outcomes, it is likely that active disease contributes to worse outcomes through the increase in emotional and physical distress that is associated with the disease and treatment-related effects.

Unexpectedly, no significant differences were found between STS and LTS on any of the health or QOL measures, suggesting that simply time out from diagnosis and treatment is not an explanation for such status after cancer, and that psychosocial effects resolve by or continue beyond the conventional five-year threshold. Given this finding, survivorship researchers might consider expanding their LTS population to include STS as a means to increase sample size and thereby enhance the power of their statistical analyses. For clinicians, this non-significant finding implies that screening for health and QOL-related issues related to having had cancer should not conclude prior to the 5-years post-diagnosis milestone for those who evidenced poor QOL earlier. Other critical elements, such as social support or the alleviation of physical symptoms, play a key role in achieving enhanced functioning, regardless of when these elements occur.

Our finding where most of our age-stratified subgroups scored lower on the MCS than the norms (i.e., met criteria for minimally important difference)33 contrasts with prior studies in which long-term survivors’ psychological health approximates that of healthy comparison groups.2,4,34 The tentative health status of lymphoma patients and the knowledge that their cancer could come back at any time may contribute to a more tenuous or labile emotional health state. However, a difference of 4.1 points on the MCS is less than half the standard deviation of 11.2 in our sample; therefore, the clinical relevance is small. Future studies are needed to examine the clinical meaning of the lower MCS scores especially in a young survivor cohort.

The relationship between having active disease and self-reported health status and QOL has important implications. For example, health care professionals may want to give closer attention to survivors with chronic (active) disease and screen for QOL-related problems. In addition, psychosocial intervention design and development should consider balancing treatment and control groups based on disease status. For example, individuals with active disease may be more likely to report worse QOL at baseline and may respond differently to specific treatment components than those who are disease-free. Finally, components of PSO (less social support, negative appraisals, and more cancer-related insurance and employment-related issues) and PTS were shown to be related to health status and QOL and are potentially modifiable.

There are several limitations in this study. As is typical for any cross-sectional study, we can not establish a cause-effect relationship between survivorship status and health and QOL status. For example, we cannot ensure that the risk factor (active disease) preceded the variables of interest (health status, QOL) due to the inability to assess this cohort over time as would be possible in a longitudinal design. Further, the sequential models adjusted for many, although likely not all, of the characteristics that might have confounded the relationship between survivorship status and outcomes. In addition, the inclusion of patients from only two large comprehensive cancer centers in NC may limit the generalizability of our results to survivors living in other regions and treated at smaller hospitals. However, our demographic profile closely mirrors that of the national population of NHL survivors,35 thereby strengthening the robustness and generalizability of our analyses. Also, the IOC was initially developed for and only tested with off-treatment survivors who are 5–10 years post-diagnosis and appropriately might not be sensitive for those in active treatment, although there are no data to support this. Also, without a matched comparison group based on socio-demographic and co-morbid conditions it is difficult to determine if these survivors had better or worse status than a similar group of people who never had cancer. However, the results of comparisons to general population norms support the need to address health status and functioning concerns in this population, as evidenced by lower PCS (for those with active disease) and MCS scores in our sample. Finally, the lower percentage of those with active disease (14%) implies less precise group mean score estimates compared to disease-free survivors.

In summary, the use of general health status and cancer-specific measures revealed significant differences between NHL survivors who reported having active disease and those who were disease-free. In addition, there were no significant differences in outcomes between STS and LTS, which challenges the current use of the 5-year mark in LTS research. These data also illustrate the value of using multiple instruments to assess areas that are particularly relevant to cancer survivors and of studying subgroups with differing disease status.

Acknowledgements

We thank our lymphoma survivors for participating in this study; Drs. Merle Mishel (UNC) and Philip Rosoff (Duke) for their insight and guidance; and Dr. Elizabeth Clipp (Duke) for her contributions during the development of this work and to the field, in general.

Supported by: NCI (R03-CA-101492), American Cancer Society Doctoral Training Grant in Oncology Social Work (DSW-0321301-SW), University of North Carolina Research Council

Footnotes

There are no financial disclosures from the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sarna L, Padilla G, Holmes C, Tashkin D, Brecht ML, Evangelista L. Quality of life of long-term survivors of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2920–2929. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trentham-Dietz A, Remington PL, Moinpour CM, Hampton JM, Sapp AL, Newcomb PA. Health-related quality of life in female long-term colorectal cancer survivors. Oncologist. 2003;8:342–349. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-4-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: A follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:39–49. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV, Vingerhoets AJ, et al. Long-term quality of life among Dutch prostate cancer survivors: Results of a population-based study. Cancer. 2006;107:2186–2196. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allareddy V, Kennedy J, West MM, Konety BR. Quality of life in long-term survivors of bladder cancer. Cancer. 2006;106:2355–2362. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart DE, Wong F, Duff S, Melancon CH, Cheung AM. "What doesn't kill you makes you stronger": An ovarian cancer survivor survey. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;83:537–542. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, Furstenberg CT, et al. Quality of life of long-term survivors of breast cancer and lymphoma treated with standard-dose chemotherapy or local therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4399–4405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carver CS, Smith RG, Petronis VM, Antoni MH. Quality of life among long-term survivors of breast cancer: Different types of antecedents predict different classes of outcomes. Psychooncology. 2006;15:749–758. doi: 10.1002/pon.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kornblith AB, Herndon JE, 2nd, Weiss RB, et al. Long-term adjustment of survivors of early-stage breast carcinoma, 20 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 2003;98:679–689. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cordova MJ, Andrykowski MA, Kenady DE, McGrath PC, Sloan DA, Redd WH. Frequency and correlates of posttraumatic-stress-disorder-like symptoms after treatment for breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:981–986. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amir M, Ramati A. Post-traumatic symptoms, emotional distress and quality of life in long-term survivors of breast cancer: A preliminary research. J Anxiety Disord. 2002;16:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith SK, Zimmerman S, Williams CS, Preisser JS, Clipp EC. Post-traumatic stress outcomes in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:934–941. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Cancer Institute. [accessed November 6, 2008];General information about adult non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Available from URL: http://www.cancer.gov.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/adult-non-Hodgkins/

- 14.American Cancer Society. [accessed November 6, 2008];What are the key statistics about non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma? Available from URL: http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_1X_What_are_the_key_statistics_for_non-Hodgkins_lymphoma_32.asp?sitearea=

- 15.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrill EF, Brewer NT, O'Neill SC, et al. The interaction of post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic stress symptoms in predicting depressive symptoms and quality of life. Psychooncology. 2008;17:948–953. doi: 10.1002/pon.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Leigh S, Ly J, Gulasekaram P. Quality of life in long-term cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22:915–922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zebrack BJ, Yi J, Petersen L, Ganz PA. The impact of cancer and quality of life for long-term survivors. Psychooncology. 2008;17:891–900. doi: 10.1002/pon.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski MA. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A Manual for Users of Version 1. Second ed. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zebrack BJ, Ganz PA, Bernaards CA, Petersen L, Abraham L. Assessing the impact of cancer: Development of a new instrument for long-term survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15:407–421. doi: 10.1002/pon.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cancer Institute. [accessed November 6, 2008];Adult non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (PDQ): Treatment. Available from URL: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/adult-non-hodgkins/HealthProfessional/page2#Section_17.

- 24.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The self-administered comorbidity questionnaire: A new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:156–163. doi: 10.1002/art.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.St. Jude [accessed November 6, 2008];Childhood cancer survivor study. Available from URL: http://www.stjude.org/stjude/v/index.jsp?vgnextoid=2c1325ca7e883110VgnVCM1000001e0215acRCRD.

- 26.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stuber ML, Christakis DA, Houskamp B, Kazak AE. Posttrauma symptoms in childhood leukemia survivors and their parents. Psychosomatics. 1996;37:254–261. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(96)71564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kornblith AB, Anderson J, Cella DF, et al. Hodgkin disease survivors at increased risk for problems in psychosocial adaptation. the cancer and leukemia group B. Cancer. 1992;70:2214–2224. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921015)70:8<2214::aid-cncr2820700833>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-4Th Edition (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weathers FW, Litz B, Herman D, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD checklist (PCL-C): Reliability, validity and diagnostic utility. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allison PD. Missing Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.SAS Institute Inc. [accessed November 6, 2008];The MIANALYZE procedure. Available from URL: http://support.sas.com/onlinedoc/913/docMainpage.jsp.

- 33.Ware JE. User's Manual for the SF-36v2 Health Survey. 2nd ed. London: Quality Metric; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Helgeson VS, Tomich PL. Surviving cancer: A comparison of 5-year disease-free breast cancer survivors with healthy women. Psychooncology. 2005;14:307–317. doi: 10.1002/pon.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Cancer Institute. [accessed November 6, 2008];SEER: 5-Year survival of patients with cancer by era 1975–1998. Available from URL: http://seer.cancer.gov/