Abstract

The Drosophila CNS midline cells constitute a specialized set of interneurons, motorneurons, and glia. The utility of the CNS midline cells as a neurogenomic system to study CNS development derives from the ability to easily identify CNS midline-expressed genes. For this study, we used a variety of sources to identify 281 putative midline-expressed genes, including enhancer trap lines, microarray data, published accounts, and the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (BDGP) gene expression data. For each gene, we analyzed expression at all stages of embryonic CNS development and categorized expression patterns with regard to specific midline cell types. Of the 281 candidates, we identified 224 midline-expressed genes, which include transcription factors, signaling proteins, and transposable elements. We find that 58 genes are expressed in mesectodermal precursor cells, 138 in midline primordium cells, and 143 in mature midline cells—50 in midline glia, 106 in midline neurons. Additionally, we identified 27 genes expressed in glial and mesodermal cells associated with the midline cells. This work provides the basis for future research that will generate a complete cellular and molecular map of CNS midline development, thus allowing for detailed genetic and molecular studies of neuronal and glial development and function.

Keywords: CNS, Development, Drosophila, Gene expression, Mesectoderm, Midline, Midline glia, Neurogenesis

Introduction

One major goal of developmental neuroscience is to understand the molecular mechanisms that generate the neurons and glia that populate the central nervous system (CNS). This includes identifying the entire complement of RNAs and proteins present in each developing and mature cell type. Recent technical achievements along with other bioinformatic, biochemical, and genetic techniques now allow comprehensive, genome-wide views regarding how genes are regulated, interact, and function to generate diverse CNS cell types.

The Drosophila CNS midline cells consist of a small number of neurons and glia (Bossing and Technau, 1994) and constitute an excellent system for neurogenomic analysis of CNS development. These cells resemble the vertebrate floorplate, which lies along the ventral midline of the spinal cord, as both tissues are important sources of developmental signals (Dickson, 2002; Ruiz i Altaba et al., 2003). Several aspects of CNS midline cell development have been well-characterized, including initial specification of the midline cells by the Single-minded (Sim) and Tango (Tgo) bHLH-PAS proteins (Crews, 2003), midline glial apoptosis (Bergmann et al., 2002), and the roles of midline cell-derived signaling in controlling axon guidance (Araujo and Tear, 2003) and ventral ectoderm formation (Kim and Crews, 1993; Schweitzer and Shilo, 1997). However, relatively little is known regarding how midline neurons and glia are generated.

The Drosophila CNS midline cells arise in the blastoderm embryo as two cellular stripes, referred to as mesectoderm anlage in statu nascendi (ISN) (Fig. 1A) (midline stages are those described by Tomancak et al., 2002). At the end of the mesectoderm ISN stage (stages 5–6), gastrulation brings the mesectodermal stripes together at the ventral midline. In the subsequent mesectoderm anlage stage (stages 7–8), the midline precursors undergo a synchronous cell division to give rise to 16 midline progenitor cells per segment (Fig. 1B). During embryonic stages 9–12, these 16 midline cells undergo cell shape changes, cell division, and differentiation to form the midline primordium (Fig. 1C). In the mature midline stage (stages 13–17), CNS midline cells undergo cell movement, apoptosis, and axonogenesis to form ~3 mature midline glia and 15–18 midline neurons.

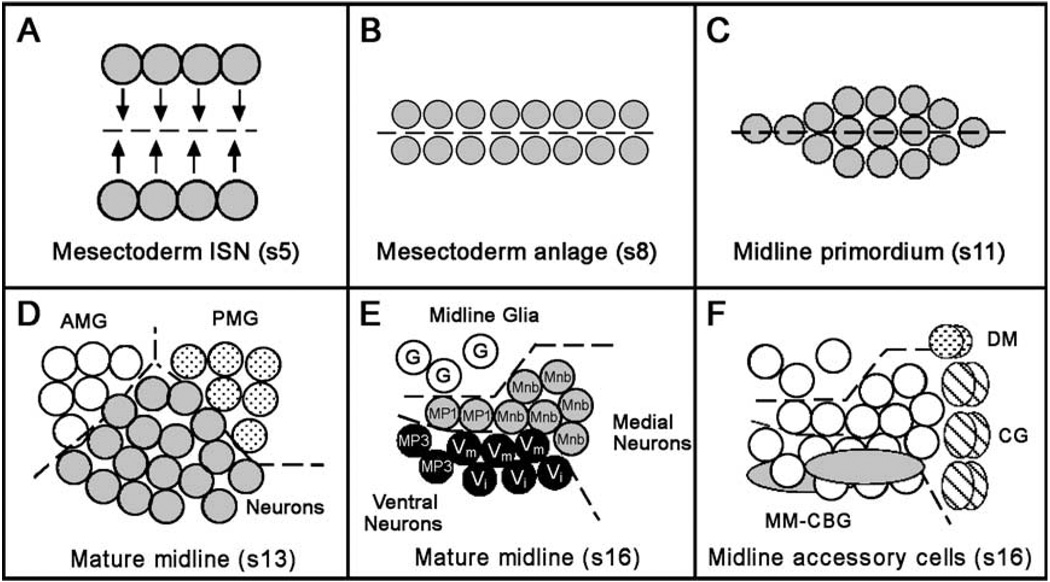

Fig. 1.

Schematic summary of CNS midline cell development. In all panels, a single segment is shown with anterior to the left. Embryonic stages are indicated by “s#”. (A) Mesectoderm ISN stage, ventral view. Two stripes of mesectodermal cells reside on either side of the mesoderm in the blastoderm embryo (stage 5). Dotted line indicates ventral midline of embryo. There are four cells/segment on each side. Arrows represent how the mesectodermal cells move together at the ventral midline during gastrulation (stage 6) as the mesoderm invaginates. (B) Mesectoderm anlage stage, ventral view. During the mesectoderm anlage stage (stages 7–8), the mesectodermal cells meet at the midline and then undergo a synchronous cell division, resulting in 16 cells per segment. (C) Midline primordium stage, ventral view. During the midline primordium stage, midline cells rearrange from a two-cell wide planar array into a cell cluster. Midline cells within these clusters differ slightly in their dorsal/ventral positions. (D) Mature CNS midline cells, stage 13. Sagittal view, dorsal up. At stage 13, two populations of midline glial cells become evident. The anterior midline glia (AMG; open circles) are reduced by apoptosis but ultimately will ensheathe the commissures while all posterior midline glia (PMG; dotted circles) will undergo apoptosis. Midline neurons (shaded circles) occupy the space between and below the midline glia. Dotted lines separate the different cell groups. (E) Mature CNS midline cells, stage 16. Sagittal view, dorsal is up. The PMG have undergone apoptosis and are absent, whereas the AMG give rise to ~3 mature glia (G, open circles). Midline neurons have migrated to their final positions within the ganglion. Medial neurons include MP1 neurons (MP1, shaded circles) and the progeny of the MNB (Mnb, shaded circles). Ventral neurons include VUM motorneurons (Vm, black circles), VUM interneurons (Vi, black circles), and MP3 neurons (MP3, black circles). (F) Midline accessory cells shown in relation to midline neurons and glia (open circles). Two DM cells (dotted circles) lie atop the CNS near the midline channel, which is lined by six-channel glia (CG; hatched ovals). The two MM-CBG in each segment (shaded ovals) are closely associated with the ventral neurons.

At the beginning of the mature midline stage, the midline glia consist of two distinct groups, anterior and posterior (Fig. 1D). The anterior midline glia, a group of ~7–8 cells, are reduced by apoptosis to ~3 cells, which become the mature midline glia (Dong and Jacobs, 1997) (Fig. 1E). The mature midline glia ensheathe the axon commissures, and their survival is dependent on axon-directed epidermal growth factor receptor (Egfr) signaling (Bergmann et al., 2002; Jacobs, 2000). The posterior midline glia are a group of ~6 cells that are spatially distinct from the anterior midline glia and, as yet, have no defined function. By stage 16, all posterior midline glia have undergone apoptosis and do not contribute to the population of mature midline glia (Dong and Jacobs, 1997).

Midline neurons (Fig. 1E) form via two distinct mechanisms, the single division of individual midline precursors (MPs) (Bate and Grunewald, 1981) and the stem cell division of the median neuroblast (MNB) (Goodman and Spitzer, 1979). In each segment, five MPs each divide once to give rise to characteristic neuronal progeny. The two MP1 interneurons are identical, while the two MP3 interneurons (H cell and H cell-sib) show different axonal trajectories and likely have different functional roles (Bossing and Technau, 1994; Schmid et al., 1999). The Drosophila ventral unpaired median (VUM) neurons consist of three interneurons and three motorneurons (Bossing and Technau, 1994; Landgraf et al., 1997; Siegler and Jia, 1999; Sink and Whitington, 1991). Based on their development, gene expression, and axonal trajectories (Goodman, 1982; Jia and Siegler, 2002), the Drosophila VUM neurons are likely homologous to the grasshopper MP4–6 neurons. Midline neurons are also generated by the single median neuroblast in each segment that divides in an asymmetric stem cell mode giving rise to five to eight neurons (Bossing and Technau, 1994). The Drosophila MNB progeny consist predominantly of interneurons, but some cells are likely to be motorneurons (Bossing and Technau, 1994).

There are also three accessory cell types that lie along the midline but are not derived from mesectodermal cells (Fig. 1F). These include (1) dorsal median (DM) cells that are mesodermal and act as guidance cues for a subset of motor axon nerves (Luer et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 1997); (2) channel glia, which line the midline channel that spans the dorsal–ventral axis of the CNS (Ito et al., 1995); and (3) medial-most cell body glia (MM-CBG) that are closely associated with and may support the VUM neurons (Ito et al., 1995).

Despite advances in our understanding of midline cell architecture, a number of aspects of midline cell development are poorly understood. These include (1) how midline neurons and glia acquire their individual cell fates; (2) how midline progenitor cells assume either a neuroblast or midline precursor mode of cell division; (3) how different MPs generate either identical or different pairs of neurons; (4) how the functional properties of midline neurons and glia are generated; and (5) how transcription factors and signaling proteins work combinatorially to control gene expression throughout midline development. One way to begin addressing these issues is to define the developmental gene expression profile of each midline cell type. To this end, we identified 224 genes expressed in midline cells and determined their spatiotemporal patterns of expression, thus establishing a database of genes expressed at all stages in all midline and midline accessory cells. This is an important step towards a comprehensive molecular and genetic analysis of CNS midline cell development and function.

Materials and methods

Drosophila strains

P[AA41-lacZ; ry+] ry, an enhancer trap line which expresses lacZ in midline glia (Crews et al., 1992), was used as the standard lab stock for in situ hybridization. The 123 enhancer trap strains with midline lacZ expression were acquired from multiple sources including our lab, Corey Goodman, W. Janning, and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. Additional lines used for cell identification were obtained from Gerd Technau, Andreas Prokop, and Corey Goodman. These include C544-Gal4 (MP1s), MzVUM-Gal4 (motorneuronal VUMs), Mz840-Gal4 (MM-CBG), Mz820-Gal4 (channel glia), and slit-Gal4 (midline glia). UAS constructs used include UAS-tau-lacZ (Hidalgo et al., 1995), and UAS-GFP-lacZ.nls (Y. Hiromi and S. West, unpublished). Microarray misexpression experiments employed daughterless-Gal4 (da-Gal4) (Giebel et al., 1997), scabrous-Gal4 (sca-Gal4) (Hinz et al., 1994), and UAS-sim-GFP (Estes et al., 2001).

Inverse PCR and sequencing of enhancer trap line genomic DNA

Genomic sequence flanking P-element insertions was determined using inverse PCR (Liao et al., 2000) and DNA sequencing on genomic DNA isolated from fly strains carrying enhancer trap insertions. One hundred twenty-three lines were sequenced. Fifteen lines had insertions at the same position as another insertion. These may represent either (1) insertions that were not independent; (2) contamination of fly stocks; (3) mislabeling; or (4) independent insertions that landed in the same location. Of the 108 independent insertions, 32 were 5′ to reported exon 1, 36 were in introns, 23 were in the 5′ untranslated region of the transcription unit, 1 was in the coding sequence, 1 was in the 3′ untranslated region, 4 were found 3′ to the transcription unit, and 11 were within or near transposable elements. Of the transposable element insertions, 10 were within the body of the element and 1 was 5′ to the element.

Microarray analysis

Embryo collection and strains

sim overexpression embryos were the progeny of UAS-sim-GFP flies (Estes et al., 2001) mated to either sca-Gal4 or da-Gal4 flies. Two control embryo populations were used: (1) yw67 and (2) UAS-sim-GFP (with no Gal4 driver present). Embryos were collected for 3 h on grape juice/agar plates and then aged for 5 h at room temperature. After collection, the embryos were dechorionated with 50% bleach, collected in PBT (1× PBS, 0.1% Triton-X-100), and kept frozen until RNA was prepared.

RNA preparation and probe generation

Total RNA was prepared from embryos using the Qiagen RNAeasy kit. Three independent RNA preparations were used in hybridization experiments for each condition. The RNA was used to generate labeled cRNA probes for microarrays. This was done by first using the RNA as a template to produce cDNA with Superscript II reverse transcriptase and a T7-(T)24 primer. Second strand cDNA was synthesized with E. coli DNA ligase, E. coli DNA polymerase, and RNase H. After second strand synthesis, the samples were purified using RNase A, proteinase K, and phenol extraction, followed by ethanol precipitation. Biotinylated antisense cRNA was produced with an Enzo Diagnostics kit. Unincorporated NTPs were removed with an RNeasy spin column, and then the samples were ethanol precipitated, quantified, and fragmented.

High-density oligonucleotide array hybridization and data analysis

After prehybridization at 45°C for 15 min, the labeled, fragmented cRNA was hybridized to Drosophila Affymetrix microarray chips for 16 h at 45°C at the UNC Functional Genomics Core Facility. After hybridization, the arrays were washed in an Affymetrix Fluidics station and stained with streptavidin-R phycoerythrin conjugate (Molecular Probes). After hybridization and washing, the expression signals of each gene were obtained by scanning the microarray chips. Values from the chips were analyzed using Affymetrix software that generated normalized average difference values for each gene. To determine the genes that are up-regulated in embryos overexpressing sim, we entered the data obtained from the Affymetrix software into GeneSpring (Silicon Genetics). The sca-Gal4 × UAS-sim-GFP embryos were compared to the yw67 embryos, while the da-Gal4 × UAS-sim-GFP embryos were compared to UAS-sim-GFP embryos. The data was normalized to median values for each gene and a t-test was performed on a gene-by-gene basis. When compared to wild-type controls, genes that had significantly increased by ≥1.2× (P < 0.05) in one of the three experimental conditions were designated as “increased”. Genes that showed ≥1.2× difference (P < 0.05) in expression levels between the two control conditions (yw67 and UAS-sim-GFP) were eliminated from the lists of increased genes.

Sources of cloned DNA

cDNA clones from the BDGP collection (v1.0 and v2.0; Open Biosystems) were used to prepare in situ hybridization probes for most genes. Two genes, CG12648 and scute, were not represented in the BDGP collection and were PCR-amplified directly from genomic DNA using gene-specific primers. The PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T easy (Promega) to facilitate in vitro transcription.

Embryo collection and fixation

Drosophila embryos were collected on grape juice agar plates. Timed collections were performed corresponding to three different staged groupings (s4–10, s11–12, and s13–17). Embryos were dechorionated by immersing in 50% bleach for 5 min. Dechorionated embryos were fixed at the interface of heptane and 4% formaldehyde/1× PBS for 30 min, suspended in 50% methanol/50% heptane, and vigorously shaken to remove vitelline membranes. Embryos were then methanol dehydrated by rinsing 5× in 100% methanol and stored at −20°C. Prior to in situ hybridization or immunostaining, the three staged groups of embryos were combined in equal proportions to achieve equal representation of all embryonic stages.

In situ hybridization

Most steps of the in situ hybridization procedure were carried out using modifications of protocols from the BDGP Methods website (http://www.fruitfly.org/about/methods/ index.html) (Tomancak et al., 2002). DNA templates for digoxigenin (dig)-labeled RNA probe preparation were PCR-amplified from individual clones such that the amplified insert was flanked by an RNA polymerase initiation site allowing in vitro antisense probe transcription. PCR amplification of inserts cloned into the pBluescript SK− and pFlc-1 vectors was carried out using the SK-30 (5′ GGG-TAA-CGC-CAG-GGT-TTT-CC 3′) and SK-Met (5′ ATG-ACC-ATG-ATT-ACG-CCA-AGC 3′) primers. To amplify inserts in the pOT2a and pOTB7 vectors, primers OT2Afor (5′ GAA-CGC-GGC-TAC-AAT-TAA-TAC-A 3′) and OT2Arev (5′ GCC-GAT-TCA-TTA-ATG-CAG-GT 3′) were used. To amplify inserts in the pGEM-T easy vector, a gene-specific primer and the M13/pUCfor (5′ CCC-AGT-CAC-GAC-GTT-GTA-AAA-CG 3′) primer were used. DNA templates were amplified from single bacterial colonies streaked from the Drosophila cDNA collections or from diluted plasmid minipreps. PCR was performed using the following conditions: 1× PCR buffer II (Applied Biosystems), 200 µM dNTP, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.3 µM each primer, 0.675 units Amplitaq DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems), and 0.015 units cloned Pfu polymerase (Stratagene). PCR cycling was preceded by a 5-min incubation at 95°C to lyse bacterial cells and followed by a 10-min incubation at 72°C. PCR cycling consisted of 35 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 50°C, and a 72°C extension starting at 5 min and increasing by 6 s each cycle. DNA templates were sized on a 1% agarose gel and precipitated with sodium acetate prior to dig-RNA probe preparation. Using these protocols, we successfully amplified 320 of the total 331 cDNAs.

Synthesis of dig-UTP RNA probes was performed in 96-well plates. To generate antisense RNA probes for each cloned cDNA, 10 µl of PCR product was ethanol precipitated, resuspended in DEPC-treated H2O, and in vitro transcribed using SP6 (New England Biolabs), T3 (Promega), or T7 (New England Biolabs) polymerases. All reactions were performed at 37°C for 3 h and contained the following: 1× transcription buffer, 10 mM DTT, 1× nucleotide labeling mix (Roche) containing dig-UTP, 20 units RNasin (Promega), and 8 units of RNA polymerase in a 10 µl final volume. RNA probes were DNase-treated with 1 µl of RQ1 DNase (Promega) for 30 min at 37°C. RNA probes were checked for size and concentration by gel electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel. All probes were fragmented by adding an equal volume of Na2CO3 (pH 10.2) and incubated at 60°C for 15 min, followed by ethanol precipitation and resuspension in 150 µl of probe resuspension buffer (50% formamide, 5 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA and 0.01% Tween-20). Transcription reactions that yielded significantly less RNA than expected were resuspended proportionally.

Hybridization was carried out in 96-well plates using an existing protocol (Tomancak et al., 2002) with the following modifications. Approximately 25 Al of embryos (encompassing stages 4–17) were hybridized with each RNA probe. Probes were diluted 1:100 in hybridization buffer (50% glycerol, 4× SSC, 5% dextran sulfate, 0.01% Tween-20) and hybridization was performed in a total volume of 100 µl at 55°C for ≥18 h. Anti-dig-alkaline phosphatase (AP) antibody (Roche) was used at 1:2000 in a total volume of 100 µl/well, and AP color reagent [175 µg/ml BCIP, 225 µg/ml NBT, 50 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris (pH 9.5), 0.01% Tween-20] was used to detect hybridization signal. The color reaction was stopped by washing embryos 5× in PTX (1× PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100).

Fluorescent development of hybridized embryos was performed using the protocol of D. Leaman and U. Gaul (personal communication). Hybridized embryos were blocked in 0.5% blocking buffer (Perkin Elmer) and incubated in anti-dig-POD antibody (Roche) diluted 1:50 in 0.5% blocking buffer for 1 h. Following three 10-min PT (1× PBS, 0.1% Tween-20) washes, embryos were incubated for 2 h in TSA-Cy3 or TSA-Cy5 diluted in amplification diluent (Perkin Elmer). TSA reactions were stopped by three 5-min PT washes. Fluorescent RNA probe development was followed by immunostaining (see below).

Stained embryos were exchanged into 70% glycerol/ 1× PBS and imaged with a Zeiss Axiophot microscope with Nomarski optics, Sony 3XDD CCD video camera, and Zeiss Axiovision software. For immunofluorescent analysis, embryos were mounted in Aqua Poly/Mount (Polysciences, Inc.). Confocal images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 510 laser scanning system equipped with individual Argon and HeNe lasers for excitation at 488, 543, and 633 nm.

Immunostaining

Fixed embryos were rehydrated for 5 min in a solution of 1:1 methanol/PTX, washed 30 min in PBT (1× PBS, 0.1% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100), and blocked 30 min in PBT-5% Normal Goat Serum (NGS). Embryos were incubated in 1° antibody diluted in PBT-NGS overnight at 4°C, washed 3× for 5 min and 4× for 30 min in PBT, and blocked for 30 min in PBT-NGS. Embryos were incubated in 2° antibody diluted in PBT-NGS for 2 h at room temperature, washed 3× for 5 min and 4× for 30 min in PBT, and visualized for fluorescence or stained with HRP. For HRP staining, embryos were incubated in diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution (1× PBS, 0.05% Tween-20, 0.3 mg/ml DAB) for 2 min and mixed with H2O2 to a final concentration of 0.03%. The 1° antibodies were used at the following dilutions: mouse anti-Engrailed (En) 4D9 (1:25) (Patel et al., 1989), rabbit anti-β-galactosidase (1:1000, Cappel), and mouse anti-Tau (1:500, Sigma). For 2° antibodies, we used α-rabbit-HRP (Sigma), α-mouse-Alexa 488, and α-rabbit-Alexa 647 (Molecular Probes) at a 1:200 dilution.

Results

Identification of midline–expressed genes

We assembled a database containing genes either known or potentially expressed in CNS midline cells. There were four sources of midline-expressed genes: (1) Drosophila enhancer trap lines; (2) microarray data for genes overexpressed in embryos that possess excess midline cells; (3) genes analyzed by in situ hybridization by the BDGP and other labs; and (4) genes identified via literature searches, annotated either by FlyBase or our-selves. While a few genes with broad expression in the CNS were included in the database, genes with ubiquitous expression or those without conspicuous midline expression were not considered.

Enhancer trap lines

There have been several P-element enhancer trap screens that identified midline-expressed genes (Crews et al., 1992; Kasai et al., 1992; Klämbt et al., 1991; Matthews and Crews, 1999; Peter et al., 2002). We accumulated 123 enhancer trap lines with detectable expression in the embryonic CNS midline cells. Several genes corresponding to P-element insertions from these screens have been previously identified and characterized (e.g., Hu et al., 1995; Klämbt, 1993; Matthews and Crews, 1999), but most have not. We used inverse PCR, DNA sequencing, and the Drosophila genome sequence to identify the location of each P-element insertion and the corresponding gene.

Sequencing of the 123 enhancer trap lines revealed 108 unique insertions corresponding to 76 distinct genes. The most prominent hot spots in this collection were pum (six insertions), CG32423 (five insertions), esg (five insertions), lola (five insertions), TE-opus (four insertions), dve (four insertions), and sog (four insertions). Eleven insertions identified 7 different transposable element families. While there were previous reports that transposable elements were expressed in midline cells (Ding and Lipshitz, 1994; Lammel and Klambt, 2001; Tomancak et al., 2002), these results indicate that this is a widespread phenomenon. Of the 76 enhancer trap genes, 46 had available cDNA clones. We find that 39 of these are expressed in the CNS midline cells (Table 1), while the remaining 7 are not.

Table 1.

Genes expressed in midline cell types at each stage of development

| Name | Function | Midline expression |

ID | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | A | P | MG | MN | DM | MM | CG | |||

| 18w | Transmembrane receptor | – | All | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5-HT1A | Serotonin receptor | – | – | – | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| 5-HT7 | Serotonin receptor | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| α-Cat | Cytoskeletal protein binding | – | – | Sub | Unc | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| Acf1 | Chromatin accessibility complex | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| aly | Spermatogenesis | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| apt | Myb domain transcription factor | – | – | All | All | – | – | – | – | ET |

| argos | EGF receptor antagonist | – | – | Sub | AMG | – | – | – | – | ET |

| ase | bHLH transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| asp | Microtubule binding | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | MA |

| β-Spec | Cytoskeletal protein binding | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| bib | Connexon channel | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| bnb | Unknown | – | All | Sub | – | – | – | X | – | – |

| brk | Transcription factor | All | All | All | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| btl | Receptor tyrosine kinase | – | Sub | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | ET |

| CaBP1 | Protein disulfide isomerase | – | – | Sub | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| cact | Transcription factor binding | – | – | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | ET |

| Cad74A | Cadherin domain | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Caki | Guanylate kinase | – | – | All | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| cas | Zinc finger transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| cdi | Receptor serine/threonine kinase | – | – | All | All | – | – | – | – | ET |

| cenB1A | ARF GTPase activator | Sub | Sub | All | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG1124 | Unknown | – | – | – | AMG | – | – | X | – | – |

| CG2165 | Calcium-transporting ATPase | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG2310 | Unknown | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – |

| CG3097 | Carboxypeptidase A | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG3168 | Carbohydrate transporter | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – |

| CG3171 | G-protein coupled receptor | – | – | – | Unc | – | – | – | – | ET |

| CG3409 | Monocarboxylic acid transporter | – | – | All | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| CG3941 | Zinc finger transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | Med | – | – | – | – |

| CG4133 | Zinc finger domain | – | – | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| CG4322 | G-protein coupled receptor | – | – | – | – | X | – | X | – | |

| CG4455 | Unknown | – | – | All | – | – | – | – | – | ET |

| CG4532 | Actin binding | – | – | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| CG4726 | Inorganic phosphate transporter | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – |

| CG5175 | Unknown | – | – | – | – | Med | – | – | – | – |

| CG5358 | Arginine N-methyltransferase | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | MA |

| CG5629 | Unknown | – | – | Sub | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| CG5746 | Unknown | – | – | – | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| CG5854 | NAD(P)-binding domain | – | – | Sub | – | Med | – | – | – | – |

| CG6070 | Amino acid transporter | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – |

| CG6201 | Hydrolase | – | – | – | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| CG6218 | Carbohydrate kinase | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | MA |

| CG6225 | Metallopeptidase | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | |

| CG6783 | Fatty acid binding | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – |

| CG7224 | Unknown | – | – | All | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG7271 | Unknown | – | – | Sub | AMG | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG7515 | Guanyl-nucleotide exchange factor | – | – | Sub | AMG | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG7663 | Unknown | – | – | Sub | PMG | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG8026 | Mitochondrial carrier | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | ET |

| CG8291 | Serotonin transporter | – | All | All | All | – | – | – | – | ET |

| CG8709 | Unknown | – | Sub | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| CG8776 | Carbon-monoxide oxygenase | – | – | Sub | AMG | – | – | – | – | ET, MA |

| CG8965 | RA domain | – | – | Sub | AMG | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG9598 | PDZ domain | All | All | All | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG9634 | Metalloendopeptidase | Sub | Sub | All | Unc | Med | – | – | – | – |

| CG10960 | Sugar transporter | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – |

| CG11248 | Microtubule binding | – | – | All | – | Unc | – | – | – | MA |

| CG11798 | Zinc finger domain | – | – | – | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| CG11880 | Transporter | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | MA |

| CG11902 | Zinc finger transcription factor | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – |

| CG12648 | bHLH transcription factor | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – |

| CG12910 | C2 calcium/lipid-binding domain | – | – | – | Unc | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG13333 | Unknown | – | – | All | Unc | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| CG13532 | Immunoglobulin domain | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| CG14059 | Unknown | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| CG14883 | Unknown | – | – | – | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| CG15236 | Unknown | – | – | – | PMG | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| CG16876 | bHLH domain | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – |

| CG30116 | Apoptotic protease activator | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| CG30342 | Unknown | – | – | – | – | All | – | – | – | MA |

| CG31116 | Voltage gated chloride channel | – | – | Sub | All | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG31145 | Nucleotide hydrolase domain | – | – | Sub | All | Ven | – | – | – | ET |

| CG31235 | Oxidoreductase | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG31634 | Organic anion transporter | – | – | – | All | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG31640 | Receptor tyrosine kinase | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| CG31757 | Phosphodiesterase | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| CG31764 | Unknown | – | – | – | AMG | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG32030 | Actin binding | – | – | Sub | All | – | – | – | – | ET |

| CG32046 | Unknown | – | – | Sub | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| CG32244 | Unknown | – | – | Sub | All | – | – | – | – | – |

| CG32423 | RNA–binding | – | – | Sub | All | Unc | – | – | – | ET |

| CG32594 | Unknown | – | – | All | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ci | Zinc finger transcription factor | – | – | All | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cnx99A | Chaperone | – | – | – | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| comm | Protein binding | – | Sub | Sub | Unc | – | – | – | – | – |

| comt | ATPase | – | – | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| Con | Structural molecule | – | – | Sub | Unc | Ven | – | – | – | ET |

| corn | Microtubule binding | – | – | Sub | Unc | – | – | – | – | ET |

| cyc | bHLH PAS transcription factor | – | – | – | – | Med | – | – | – | – |

| Cyc E | Cyclin-dependent protein kinase | Sub | Sub | – | – | Med | – | – | – | – |

| D | HMG transcription factor | All | All | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| danr | Homeobox containing | – | Sub | – | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| Dg | Cytoskeletal anchoring | – | – | All | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Dgk | Diacylglycerol kinase | – | – | – | Unc | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| Dip3 | Unknown | – | – | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | MA |

| Dl | Notch binding receptor | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| dpld | Zinc finger transcription factor | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – |

| dpn | bHLH transcription factor | Sub | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| dve | Homeobox transcription factor | – | – | All | AMG | Med | – | – | – | ET |

| E2F | E2F transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Eaat1 | Amino acid transporter | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – |

| Eaat2 | Amino acid transporter | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| Ect3 | Beta-galactosidase | Sub | Sub | All | All | – | – | – | – | – |

| edl | MAPK signaling component | – | All | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Egfr | Receptor tyrosine kinase | Sub | – | – | All | – | – | – | – | – |

| emc | HLH transcriptional corepressor | – | – | – | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| en | Homeobox transcription factor | Sub | Sub | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | ET |

| Epac | Guanyl-nucleotide exchange factor | – | – | Sub | All | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ephrin | Ephrin receptor binding | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| esg | Zinc finger transcription factor | – | Sub | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | ET |

| Fas1 | Fas domain | – | Sub | Sub | – | Unc | X | – | – | – |

| fd59A | Forkhead transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| FK506-bp2 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | ET |

| futsch | Microtubule binding | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| Gad1 | Glutamate decarboxylase | – | – | – | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| Gdi | GDP–dissociation inhibitor | – | – | Sub | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| GH22170 | Unknown | – | – | Sub | All | – | – | – | – | ET |

| glec | Carbohydrate binding | – | All | Sub | All | – | – | – | – | ET |

| Gli | Serine esterase | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – |

| Glu-RI | Glutamate–gated ion channel | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| gsb-n | Homeobox transcription factor | Sub | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| gukh | Unknown | All | All | Sub | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| HGTX | Homeobox transcription factor | – | All | All | – | Med | – | – | – | – |

| HLHm β | bHLH transcription factor | All | All | All | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hrb87F | RNA binding | – | – | – | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| jing | Zinc finger transcription factor | – | – | – | All | – | – | – | – | – |

| kek1 | Receptor serine/threonine kinase | – | – | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | ET |

| klar | ATPase | All | – | Sub | – | Unc | – | – | – | ET |

| klg | Immunoglobulin domain | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | ET | |

| Klp61F | Microtubule motor protein | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| knrl | Zinc finger transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Kr | Zinc finger transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| Kr-h1 | Zinc finger transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| l(1)G0003 | C2 calcium/lipid-binding domain | – | – | Sub | All | – | – | – | – | ET |

| l(1)sc | bHLH transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| l(2)02045 | Regulator of G-protein signaling | – | – | – | AMG | – | – | – | – | – |

| lbm | Receptor signaling protein | – | – | – | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| lcs | Unknown | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| lin-28 | Zinc finger domain | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| mab-2 | Unknown | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| mam | Unknown | – | – | – | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| mas | Serine-type endopeptidase | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mcm5 | DNA helicase | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mdh | Malate dehydrogenase | – | – | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | ET |

| Mdr65 | Multidrug transporter | – | – | – | Unc | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mes2 | Unknown | Sub | Sub | Sub | – | – | X | – | – | MA |

| mfas | Fas domain | – | – | All | Unc | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mmp1 | Metalloendopeptidase | – | – | Sub | – | – | X | – | – | – |

| nerfin–1 | Zinc finger transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | Med | – | – | – | – |

| NetA | Secreted protein | – | All | Sub | All | – | – | – | – | – |

| NetB | Secreted protein | – | – | Sub | All | – | – | – | – | – |

| neur | Ubiquitin-protein ligase | All | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | ET |

| Nmdar1 | Ligand-gated ion channel | – | – | – | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| NPFR1 | Neuropeptide receptor | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| NPFR76F | Neuropeptide receptor | – | – | – | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| Nrg | Immunoglobulin domain | – | – | – | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| nrv1 | Na/K-exchanging ATPase | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – |

| nrv2 | Na/K-exchanging ATPase | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – |

| nub | Homeobox transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| nvy | TAF domain transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| oaf | Unknown | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| odd | Zinc finger transcription factor | Sub | – | Sub | – | Med | – | – | – | – |

| Orct | Organic cation transporter | – | – | All | – | – | – | – | – | MA |

| pdm2 | POU Homeobox transcription factor | – | Sub | – | – | Med | – | – | – | – |

| Pitslre | Receptor serine/threonine kinase | – | – | – | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| ple | Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| prc | Matrix component | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – |

| pros | Transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ptp99A | Receptor tyrosine phosphatase | – | – | – | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| Pvf3 | VEGF receptor binding | – | – | Sub | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| pxb | Unknown | Sub | Sub | Sub | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| ran | Small monomeric GTPase | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ref(2)P | Transcription factor | – | – | – | – | Med | – | – | – | – |

| repo | Homeobox transcription factor | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | – |

| rhea | Actin binding | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| rho | Serine-type peptidase | All | All | All | PMG | Ven | – | – | – | ET |

| robo | Transmembrane receptor | – | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| rst | Immunoglobulin domain | – | – | All | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| S | EGF ligand processing | – | All | All | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| sc | bHLH transcription factor | All | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| sca | Receptor binding | All | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| scb | Laminin receptor | – | – | – | PMG | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sema-1b | Receptor | All | All | All | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sema-5c | Receptor | Sub | Sub | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | ET |

| sim | bHLH PAS transcription factor | All | All | All | All | – | – | – | – | – |

| slp2 | Forkhead transcription factor | Sub | Sub | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| sna | Zinc finger transcription factor | – | – | All | All | – | – | – | – | – |

| SNF4Ag | Receptor serine/threonine kinase | – | – | Sub | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| sno | Unknown | All | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| sob | Zinc finger transcription factor | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| sog | Torso signaling | All | All | All | – | – | – | – | – | ET |

| Stat92E | SH2 transcription factor | Sub | Sub | All | – | – | – | – | – | ET |

| stg | Protein tyrosine phosphatase | – | All | – | Unc | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| Sulf1 | N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfatase | – | – | Sub | – | Med | – | – | – | – |

| SytIV | Phospholipid binding | – | – | – | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| tap | bHLH transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | Med | – | – | – | – |

| TE 1731 | Transposable element | – | – | – | – | Unc | – | – | – | – |

| TE 412 | Transposable element | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | – | – |

| TE Beagle | Transposable element | – | – | – | AMG | Unc | – | – | – | ET |

| TE copia | Transposable element | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| TE Doc | Transposable element | – | – | All | – | Ven | – | – | – | ET |

| TE Rt1a | Transposable element | – | All | – | – | All | – | – | – | ET |

| th | Ubiquitin–protein ligase | Sub | – | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | ET |

| timeout | Myb DNA binding domain | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| tkr | BTB/POZ domain | – | – | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | ET |

| tkv | Type I TGF-β receptor | – | All | – | AMG | – | – | – | – | – |

| Tl | Cytokine binding | – | – | All | – | Ven | – | – | – | ET |

| tok | Procollagen C-endopeptidase | – | – | All | – | All | – | – | – | – |

| Tom | Unknown | All | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Traf1 | Receptor binding | Sub | – | Sub | – | Med | – | – | – | – |

| trbl | Receptor serine/threonine kinase | Sub | – | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | ET |

| trf2 | General transcription factor | – | – | All | Unc | Unc | – | – | – | ET |

| tsl | Torso binding | – | Sub | Sub | All | – | – | – | – | – |

| Tsp42Ee | Unknown | – | – | – | – | Ven | – | – | – | – |

| twi | bHLH transcription factor | All | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ubx | Homeobox transcription factor | – | – | All | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| vvl | POU Homeobox transcription factor | – | – | All | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| wg | Frizzled-2 binding | Sub | Sub | Sub | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Wnt8 | Wnt family | All | All | All | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| wor | Zinc finger transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | Med | – | – | – | |

| wrapper | Immunoglobulin domain | – | – | Sub | All | – | – | – | – | – |

| zfh1 | Zinc finger transcription factor | All | All | Sub | – | Ven | X | – | – | – |

| zfh2 | Zinc finger transcription factor | – | – | Sub | – | All | – | – | – | |

I—mesectoderm ISN; A—mesectoderm anlage; P—midline primordium: All—all midline cells; Sub—subset of midline cells. MG—midline glia: AMG— anterior midline glia, PMG—posterior midline glia, All—all midline glia, Unc—uncertain midline glial localization. MN—midline neurons: Ven—ventral midline neurons, Med—medial midline neurons, All—all midline neurons, Unc—uncertain midline neuronal localization. DM—dorsal median cell, MM— MM-CBG; CG—channel glia: X—expression. ID, identification: ET—enhancer trap, MA—microarray. Functional assignments provided by Flybase.

Microarray analysis

When sim is misexpressed in the neuroectoderm, a number of genes expressed in midline cells are ectopically expressed throughout the lateral CNS (Estes et al., 2001; Nambu et al., 1991). We used this paradigm to identify additional genes expressed in the CNS midline cells by comparing RNA populations between wild-type and sim misexpression embryos using microarrays. We used the Gal4/UAS system to misexpress a functional Sim-GFP fusion protein throughout the neuroectoderm and CNS using sca-Gal4 and da-Gal4. Control and experimental RNA from these misexpression embryos were labeled and hybridized to Affymetrix Drosophila GeneChips. We made RNA comparisons during the midline primordium stage, a time when midline progenitors are developing into midline neurons and glia.

Of the 13,601 genes arrayed on the chip, the da-Gal4 × UAS-sim-GFP embryos had 380 genes up-regulated with 77 up-regulated ≥2× (data available upon request). sca-Gal4 × UAS-sim-GFP embryos had 419 genes up-regulated with 112 increased ≥2×. Examination of the up-regulated genes revealed several points. (1) The positive control genes, sim and wrapper, which are relatively specific for midline cells (Crews et al., 1988; Noordermeer et al., 1998), were increased in both paradigms. wrapper was increased 3× (P < 0.03) in da-Gal4 × UAS-sim-GFP and 3× (P < 0.02) in sca-Gal4 × UAS-sim-GFP embryos. sim was increased 15× (P < 0.03) in da-Gal4 × UAS-sim-GFP and 6× (P < 0.01) in sca-Gal4 × UAS-sim-GFP embryos. However, in these experiments, we were unable to distinguish the relative contributions of sim misexpression and sim autoactivation. (2) Few genes [25] were up-regulated in both paradigms. Furthermore, no gene showed expression ≥2× in both paradigms, with the exception of sim and wrapper. (3) While a number of genes known to be expressed in the CNS midline cells were up-regulated in one or more paradigms [17], most of the midline-expressed genes studied by in situ hybridization in this report (see below) were not. (4) Many genes up-regulated in one or more of the paradigms do not show midline expression according to published reports.

We tested 21 genes that were up-regulated in sca-Gal4 × UAS-sim-GFP embryos compared to wild-type by in situ hybridization (Table 1). Six genes showed midline expression, 14 had expression elsewhere (gut expression was common), and 1 did not show any embryonic expression. The expression of the six genes showing midline expression was not specific to midline cells and midline expression was weak or transient. While the microarray experiments allowed identification of novel midline-expressed genes, the approach had many false positives and failed to identify many midline-expressed genes. This may be due, in part, to the restriction of our analysis to mid-embryogenesis (stages 11–12), which will not identify genes expressed later in midline development. Moreover, most midline-expressed genes are expressed in many non-midline cell types during mid-embryogenesis. Since mid-line cells constitute only ~2% of all embryonic cells, the use of whole embryos to isolate RNA likely increases background expression, and thus decreases signal to noise ratios for broadly expressed genes.

Midline genes identified from Drosophila databases

There were 89 genes annotated in FlyBase as of February 2004 that have midline expression based on published accounts. The BDGP gene expression site (Tomancak et al., 2002) has identified 132 genes that are expressed in CNS midline cells. All categories that denote expression in CNS midline cells were included for analysis. Another database, listed on FlyBase (Consortium, 2003), contains ESTs derived from embryonic membrane-bound polysomal RNA (Kopczynski et al., 1998) that includes 22 genes expressed in CNS midline cells. Additional midline-expressed genes were identified by inspection of various published articles (e.g., Brody et al., 2002; Freeman et al., 2003). There is overlap between genes contained in these data sets, and including all sources, we identified 387 potential midline-expressed genes. Although these genes are reported to be expressed in midline cells, our analysis extends these findings by carefully mapping the spatiotemporal expression profile of each gene with respect to each midline cell type.

In situ hybridization experimental results

Of the 387 potential midline-expressed genes in our database, cDNA clones were available for 331. For each of these 331 cDNAs, dig-labeled RNA probes were generated and hybridized to staged Drosophila embryos using a 96-well plate procedure. In this study, we define CNS midline cells as those cells that lie along the CNS midline including cells derived from sim-positive mesectodermal cells (MP1, MP3, VUM, MNB, and midline glial lineages), as well as the mesodermal DM cells, and MM-CBG and channel glia that are both derived from the lateral CNS and migrate to the midline. The only exceptions are the apoptotic cells that accumulate at the midline between the CNS and epidermis in late stage embryos. These cells were ignored for the purposes of this analysis. Of the 331 genes assayed, 282 showed detectable hybridization with 224 expressed in midline cells.

Expression profiles of CNS midline-expressed genes

To create a database of midline gene expression profiles, we analyzed embryos at each developmental stage pertinent to embryonic CNS development (stages 5–17) (Campos-Ortega and Hartenstein, 1997). These stages include (1) mesectoderm ISN (stages 5–6); (2) mesectoderm anlage (stages 7–8); (3) midline primordium (stages 9–12); and (4) mature midline cells (stages 13–17) (Fig. 1). The annotation of these developmental time periods corresponds to the terminology proposed by the BDGP gene expression group (Tomancak et al., 2002). It is common for genes to be expressed in multiple stages and in multiple midline and lateral CNS cell types. Using alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining we can identify gene expression in subsets of midline cells. The anterior and posterior midline glia occupy opposite ends of the midline segment while midline neurons can be recognized as medial neurons (MP1 and MNB progeny) or ventral neurons (MP3 and VUM) based on their position in the segment. Midline accessory cells also occupy characteristic positions with respect to the mature midline cells. Definitive identification of expression in individual cell types requires confocal analysis (see below), and will, largely, be the subject of subsequent work. Table 1 summarizes the expression profile of each gene during each time period and in each mature cell type.

Mesectoderm ISN expression (stages 5–6)

The mesectoderm ISN occurs in blastoderm and gastrula stage embryos (stage 5–6) when mesectodermal cells cannot be recognized by morphology but only by gene expression (Fig. 1A and Fig. 2). We find 37 genes expressed in the mesectoderm ISN. These include transcription factors (14) and proteins implicated in cell signaling (12), consistent with early roles for these genes in dictating midline cell fates. We have subdivided these into two categories: genes expressed in all mesectoderm ISN cells (18) and genes expressed in a subset of mesectoderm ISN cells (19). Representatives of each of these classes of mesectoderm ISN-expressed genes are shown in Fig. 2 while a comprehensive list is found in Table 1. Not included are gap genes and others with either widespread or narrowly restricted expression patterns that are unlikely to play a role in the development of mesectoderm ISN cells or their progeny. Of the 18 genes expressed in all mesectoderm ISN cells, some are expressed exclusively in the mesectoderm, such as sim, HLHmβ, Sema-1b, and CG9598 (Figs. 2A–D), whereas others including brk and Tom are expressed in the mesectoderm and neuroectoderm (Figs. 2E–F). There is a significant body of work describing the regulation of mesectoderm ISN gene expression by the embryonic dorsal–ventral (D/V) patterning cascade and the Notch signaling pathway (Kasai et al., 1998; Morel and Schweisguth, 2000; Stathopoulos and Levine, 2002), thus providing many tools to understand the regulation of these mesectoderm ISN-expressed genes.

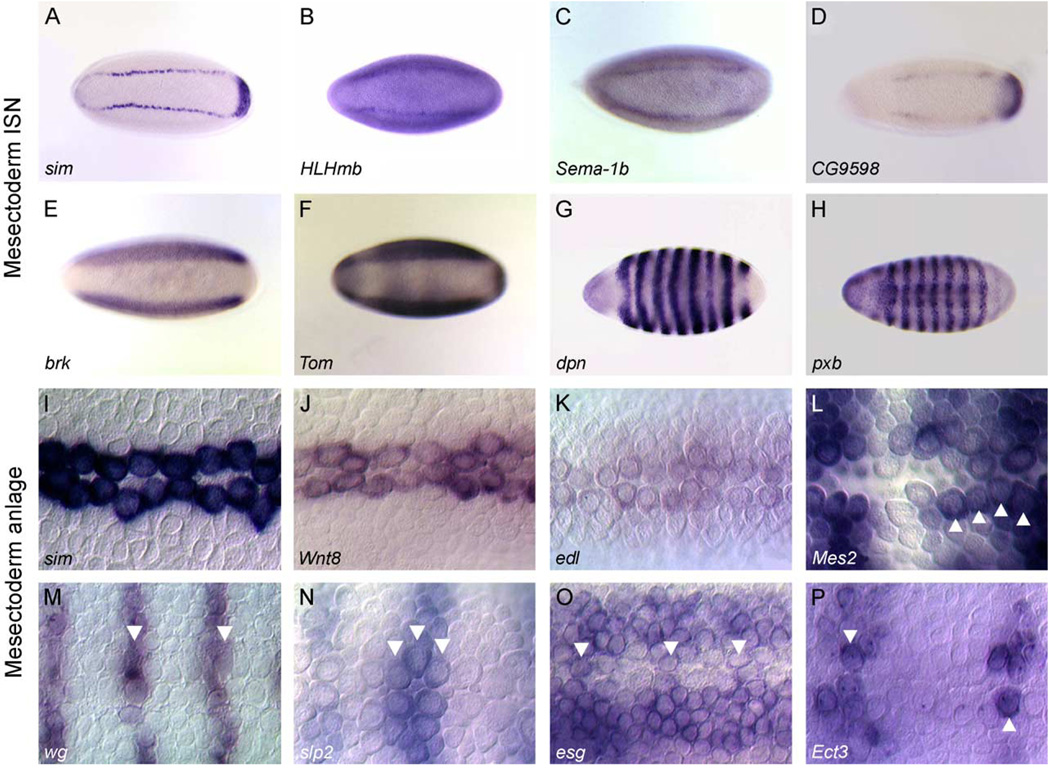

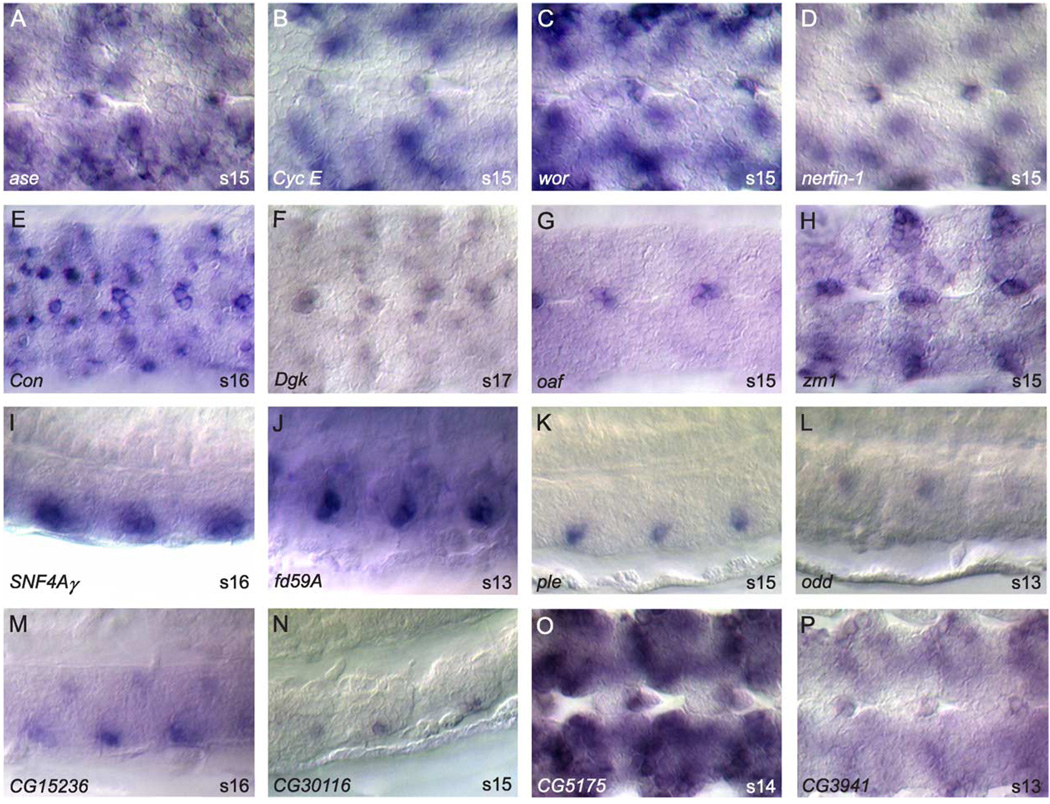

Fig. 2.

Gene expression during the mesectoderm ISN and mesectoderm anlage stages. Whole-mount embryos hybridized in situ showing the expression patterns of genes expressed in: (A–H) mesectoderm ISN, and (I–P) mesectoderm anlage. All views are ventral with anterior to the left. Gene names are shown at the bottom left. Representative genes are shown for three classes of mesectoderm ISN expression: (A–D) genes with relatively specific expression in all mesectoderm ISN cells, (E–F) genes expressed in all mesectoderm ISN cells and showing additional expression in other neuroectodermal cells, and (G–H) genes with pair-rule patterns expressed in subsets of mesectoderm ISN cells. (I–P) Shown are genes expressed in: (I–K) all mesectodermal anlage cells, and (L–P) subsets of mesectodermal anlage cells. Arrowheads indicate stained mesectodermal cells. Note the number of mesectoderm anlage cells labeled per hemisegment varies for different genes. Magnification is 12.5× for A–H and 80× for I–P.

Genes that are expressed in subsets of mesectoderm ISN cells are expressed as either repeating stripes that bisect the mesectoderm ISN or small numbers of mesectoderm ISN cells. These genes include the well-known segmentation genes, such as dpn (Fig. 2G), pxb (Fig. 2H), wg, en, gsb-n, and slp2 as well as additional genes such as Sema-5c, Mes2, and Ect3. Although their functions in midline cells are unclear, many of these genes are likely involved in defining different classes of midline cell types (Hummel et al., 1999), similar to their roles in intrasegmental patterning of the epidermis and lateral CNS (Bhat, 1999).

Mesectoderm anlage expression (stages 7–8)

The mesectoderm anlage stage occurs after gastrulation (stages 7–8) when the two populations of mesectoderm ISN cells meet at the ventral midline and undergo a synchronous cell division producing 16 midline cells per segment (Fig. 1B) (Foe, 1989). There are 22 genes expressed in all mesectoderm anlage cells, including sim, Wnt8, and edl (Figs. 2I–K), and 19 expressed in subsets, including Mes2, wg, slp2, esg, and Ect3 (Figs. 2L–P). More than half of these genes (22/41) are also expressed in the mesectoderm ISN in similar patterns. Only 10 genes expressed in all mesectoderm anlage cells and six in subsets of cells initiate transcription during this stage. Consistent with roles in regulating the division and fate of midline cells, this newly expressed group includes genes involved in cell division (CycE, stg), transcriptional control (esg, Hgtx), and cell signaling (btl, edl, tkv, tsl).

Midline primordium expression (stages 9–12)

During the midline primordium stage, midline precursor cells divide, change shape, migrate, and differentiate. There are 138 genes expressed in the midline primordium (Table 1; Fig. 3). All but six of the genes expressed in the mesectoderm anlage continue expression in the midline primordium. However, eight genes, including rho and vvl, refine their expression from all mesectoderm anlage cells to a subset of midline primordium cells. In contrast, four genes, including CenB1A and Stat92E, expand their expression from subsets of mesectoderm anlage to all midline primordium cells. Of note, 67% (92/138) of the midline primordium-expressed genes initiate their expression during this stage. Several genes (37) are expressed in all midline primordium cells (Figs. 3A–D) including cdi, CenB1A, Ect3, mfas, rho, sog, Tl, and Wnt8. These genes mimic the expression pattern of sim and are likely direct transcriptional targets of SimDTgo heterodimers (Ohshiro and Saigo, 1997; Sonnenfeld et al., 1997; Wharton et al., 1994; Zelzer and Shilo, 2000). Most genes at this stage are expressed in cellular subsets (101) (Figs. 3E–X). These genes label a range of subsets including large and small groups of cells (Figs. 3E–L) as well as single cells (Figs. 3M–P) and are noteworthy since they reveal the subdivision of midline progenitors into distinct cell types. It is likely that these genes are regulated by SimDTgo in combination with other transcription factors. Of note, a large number of transcription factors are expressed in subsets of midline primordium cells (see below). Many of the midline primordium-expressed genes are also expressed in mature midline neurons (41; Figs. 3Q–R) and glia (35; Figs. 3S–T) and will be useful in determining developmental relationships between midline primordium and mature midline cells.

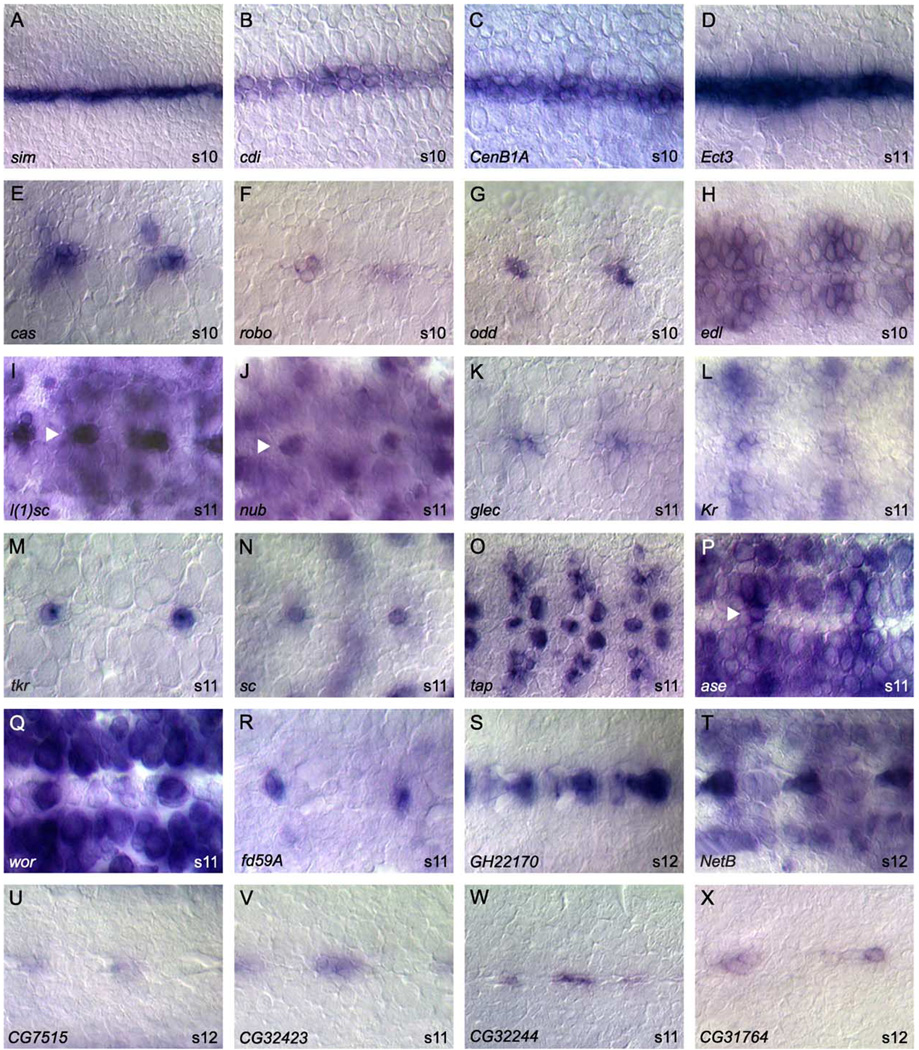

Fig. 3.

Midline primordium gene expression. Whole-mount stages 9–12 embryos hybridized to RNA probes. All views are ventral with anterior to the left. Arrowheads denote midline cells in embryos with high surrounding expression. Representatives of two major classes of gene expression are shown: (A–D) expression in all midline cells, and (E–X) expression in subsets of midline cells. Genes expressed in subsets can be further divided into those expressed in: (E–L) multiple primordium cells, and (M–P) single primordium cells. (Q–T) A subset of genes expressed in the primordium stages maintains expression in (Q–R) mature midline neurons or (S–T) midline glia. Compare (S) GH22170 in the primordium to GH22170 in the mature midline glia (Figs. 4A–B), and (Q) wor in the primordium to wor in midline neurons (Fig. 5C). (U–X) Shown are genes of currently uncharacterized function expressed in subsets of midline primordium cells. Magnification is 80× for all except Q (100×).

The 138 genes expressed in midline primordium cells include characterized (Figs. 3E–R, T) and uncharacterized (Figs. 3S, U–X) genes. Transcription factors compose the largest class. There are 40 putative transcription factors, including 15 zinc finger proteins, 9 homeobox proteins, and 7 bHLH proteins. Interestingly, zinc finger genes such as cas and Kr (Figs. 3E, L) play prominent roles in generating ganglion mother cell (GMC) diversity in the lateral CNS (Isshiki et al., 2001; Kambadur et al., 1998) and may play a similar role in generating the diversity of MNB progeny. Another set of related zinc finger proteins that function together in development of the lateral CNS neurons are esg, sna, and wor (Fig. 3Q) (Ashraf and Ip, 2001; Ashraf et al., 1999; Cai et al., 2001). All three are expressed in the midline primordium and have different expression profiles that likely overlap in some midline cells. An additional set of genes important in lateral CNS development and expressed in the midline primordium are the proneural genes sc and l(1)sc (Figs. 3I, N). Similar to their role in lateral CNS neuroblast formation (Jimenez and Campos-Ortega, 1990; Skeath and Doe, 1996), these genes may be important for the formation, differentiation, and division of the MNB and its progeny.

Another 41 genes expressed in the midline primordium are membrane or intracellular signaling proteins or membrane receptors involved in cell adhesion. These genes include argos, btl, glec (Fig. 3K), robo (Fig. 3F), Tl, tsl, and wrapper, some of which have been shown to be important for midline cell migration, apoptosis, midline-controlled axonogenesis, and glial-neuron interactions (Jacobs, 2000).

Mature midline cells (stages 13–16): midline glial expression

The midline glia are specified as two separate populations of cells, anterior and posterior, that are reduced by apoptosis to generate the ~3 mature midline glia in each segment. We identified 50 genes expressed in midline glia (Table 1; Fig. 4). Most (22) are expressed in both anterior and posterior midline glia (Figs. 4A–D), 11 are expressed prominently in anterior midline glia (Figs. 4E–H), and 4 are expressed prominently in posterior midline glia (Figs. 4 I–L). An additional 13 genes are expressed in midline glia, but it is unclear whether they are expressed in all or a subset of midline glia. Many of the genes expressed in midline glia are also expressed in the midline primordium (35/50), potentially providing markers for glial precursors in the primordium stage. Several genes (10) are expressed in both midline glia and other glial cells (Figs. 4M–N), indicating that midline and lateral glia can share glial-expressed genes. Additionally, 13 genes are expressed in both midline glia and midline neurons (Figs. 4O–P). Genes expressed in midline glial cells are varied in nature, including transcription factors, signaling proteins for the spitz, netrin, and slit pathways, intracellular signaling proteins, and genes whose functions have not been tested experimentally (Figs. 4A–B, E–H, K–N, P). There are also genes, including CG8291, CG31116, CG31634, and Mdr65, that resemble ion channels and transport proteins that may be involved in glial function.

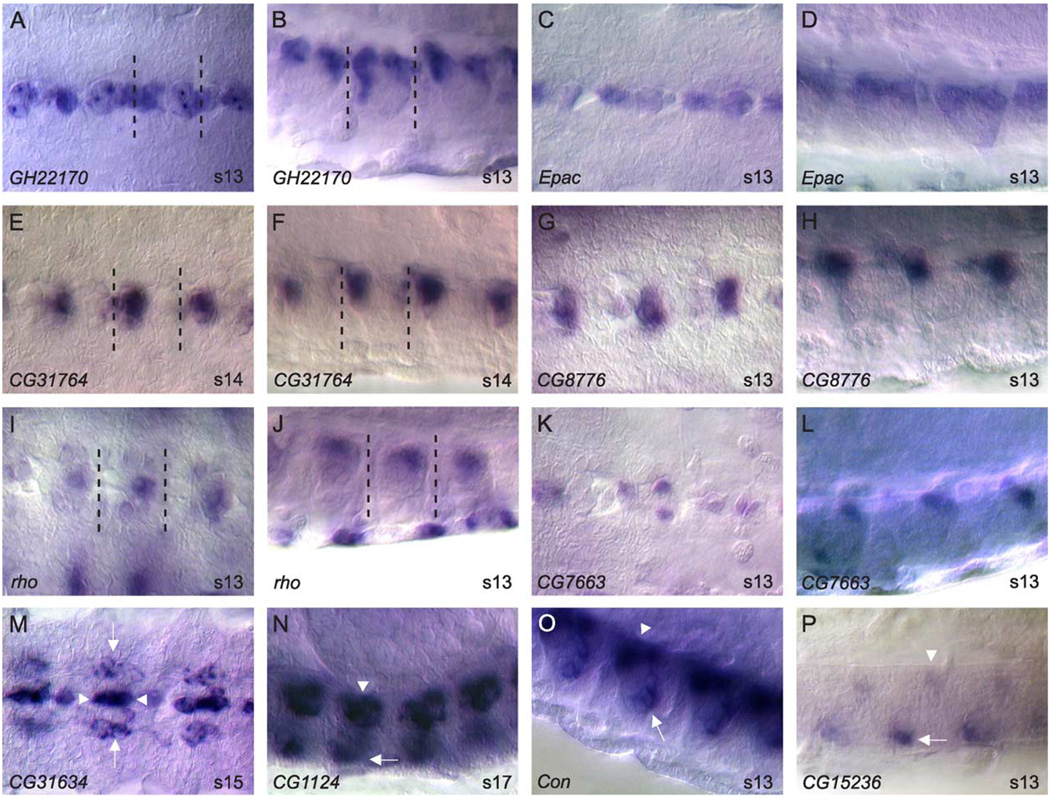

Fig. 4.

Midline glial gene expression. Whole-mount stages 13–17 embryos hybridized to RNA probes. (A–L) Each gene is shown twice with a ventral view on the left and sagittal view on the right. Anterior is left and dorsal top for sagittal views. Dotted lines enclose a single ganglion. (A-D) Two genes expressed in both anterior and posterior midline glia. (E–H) Two genes expressed prominently in anterior midline glia. (I–L) Two genes expressed prominently in posterior midline glia. (M–P) Ventral (M) or sagittal (N–P) views of embryos hybridized with probes to genes expressed in midline glia and other cell types. (M) CG31634 is expressed in both midline glia (arrowhead) and longitudinal glia (arrow). (N) CG1 124 is expressed in both midline glia (arrowhead) and MM-CBG (arrow). (O–P) Examples of genes expressed in both midline glia (arrowhead) and midline neurons (arrow). Magnification is 80x.

Mature midline cells (stages 13–16): midline neuronal expression

Midline neurons consist of a number of different interneurons and motorneurons from distinct midline lineages. We have identified 106 genes expressed in mature midline neurons: 52 in subsets of midline neurons, 29 in all or most midline neurons, and 25 whose expression is too complex or obscured to make an accurate assignment (Table 1; Fig. 5). Approximately half of these genes (51) initiate expression during the midline primordium stage, suggesting that many neuronal cell fates are likely determined prior to the mature midline stages (Table 1; compare Fig. 4Q to Fig. 5C and Fig. 4R to Fig. 5J). Genes expressed in the mature midline neurons can be categorized by their appearance in the medial or ventral regions of the CNS (Fig. 1E). The medial group includes the two MP1 neurons and the 5–8 MNB progeny, while the ventral group includes the MP3 and VUM neurons. Of the 52 genes identified in subsets of midline neurons, 16 are expressed in medial neurons (Fig. 5A–D, L, O–P) and 36 in ventral neurons (Fig. 5E–H, I–K, M–N). Among genes expressed in midline neurons, notable are genes associated with neural function. These include neurotransmitter receptors (Glu-RI, 5-HT1a, 5-HT7, Nmdar1, NPFR1, NPFR76F) and proteins involved in neurotransmitter synthesis (Gad1, ple). In addition, this class contains many functionally uncharacterized genes (Fig. 5M–P). With their well-defined complement of gene expression, midline neurons will be a useful system for studying the molecular genetics of neural function.

Fig. 5.

Midline neuronal expression. Whole-mount stages 13–17 embryos hybridized to RNA probes. Anterior is to the left and dorsal top for sagittal views. (A–H) Ventral views of genes expressed in: (A–D) medial neurons, and (E–H) ventral neurons. (I–L) Sagittal views showing the dorsal/ventral position of genes expressed in (I–K) ventral neurons and (L) medial neurons. (M–P) Examples genes of uncharacterized function expressed in (M–N) ventral neurons (sagittal views), and (O–P) medial neurons (ventral views). Magnification is 80x.

Mature midline (stages 13–16): midline accessory cell expression

A number of cells that lie along the CNS midline are derived from the lateral CNS or mesoderm. These include the MM-CBG, channel glia, and DM cells. Some of the genes that are expressed in the MM-CBG and channel glia were previously described in a genome-wide search for glial-expressed genes (Freeman et al., 2003). While a systematic analysis of accessory cell gene expression was not a major goal of this screen, a number of genes described from various sources as “midline” are expressed in accessory cells, and for this reason they have been included.

The MM-CBG consist of two to four glial cells per segment (two in abdominal and four in thoracic segments) that lie adjacent to the VUM neurons (Fig. 1F) (Ito et al., 1995). Their function is unknown; however, due to their close proximity, MM-CBG may act as support cells for the VUM neurons. These cells originate from lateral CNS neuroblast 6–4 and then migrate to their final position adjacent to the midline (Higashijima et al., 1996; Schmidt et al., 1997). MM-CBG can be recognized based on their cell morphology, location, and co-localization with Mz840–Gal4, an enhancer trap line expressed in MM-CBG (Fig. 6I–L) (Ito et al., 1995). We identified 12 genes expressed in MM-CBG (Table 1; Fig. 6A, B, I–L). Two genes, CG1124 (Fig. 6A, I–L) and nrv2, were also expressed in midline glia. The genes expressed in MM-CBG are characteristic of glia, and include five that encode transporters (CG6070, CG10960, Eaat1, nrv1, nrv2). Studying the MM-CBG and VUM neurons will potentially provide insight into glial–neuronal interactions.

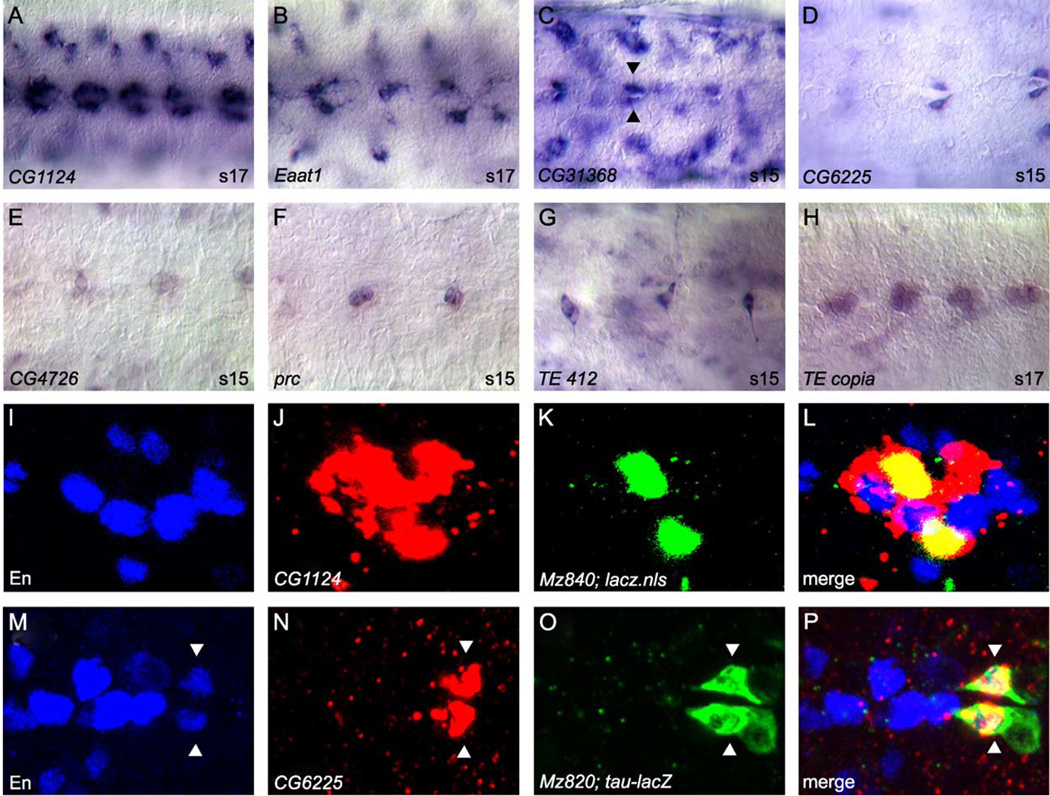

Fig. 6.

Midline accessory cell gene expression and midline-expressed transposable elements. (A–H) Whole-mount stage 15 or 17 embryos were hybridized to RNA probes and visualized by AP/DIC imaging. All views are ventral with anterior to the left. Magnification is 80x. (A–G) Examples of genes expressed in subsets of midline accessory cells, including (A–B) MM-CBG, (C–D) channel glia (arrowheads), and (E–G) DM cells. (G–H) Transposable element expression in midline and accessory cells, including (G) DM cells and (H) ventral neurons. (I–P) Confocal images of multi-label fluorescent in situ hybridization. An individual ganglion is shown for each panel. All views are ventral with anterior to the left. (I–L) Stage 16 Mz840-Gal4 × UAS-GFP-lacZ.nls embryo co-labeled with: (I) anti-En, (J) CG1124 RNA probe, and (K) anti-β-gal. (L, merge image) CG1124 expression (red) colocalizes with Mz840- driven nuclear β-gal (green) expression in MM-CBG. MM-CBGs are positioned just lateral to En-positive VUM cells. The in situ fluorescence stains the cytoplasm and is usually broader than the nuclear staining observed with immunostaining of GFP-lacZ.nls or nuclear proteins. (M–P) Stage 15 Mz820-Gal4 × UAS-tau-lacZ embryo co-labeled with: (M) anti-En, (N) CG6225 RNA probe, and (O) anti-β-gal. (P, merge image) CG6225 expression (red) co-localizes with tau-lacZ fusion protein (green) expressed in channel glia (arrowheads) via the Mz820-Gal4 enhancer trap line. CG6225-positive channel glia also express en.

The channel glia consist of six cells, two located dorsally, two medially, and two ventrally, that line the channel that lies along the midline between the posterior commissure and anterior commissure of the next ganglion (Fig. 1F) (Ito et al., 1995). Like MM-CBG, the channel glia are derived from non-mesectodermal cells, including lateral CNS neuroblast 7–4, and migrate towards the midline (Schmidt et al., 1997). Channel glia can be identified based on their glial-like morphology, their location along the midline channel, and expression of previously identified markers, Mz820–Gal4 (Fig. 6O) and en (Fig. 6M) (Ito et al., 1995). In our AP screen, six genes were found to be expressed in channel glia (Table 1; Fig. 6C, D, M–P). In addition to repo, a transcription factor shown to be expressed in many glia including channel glia (Ito et al., 1995), the functions of other channel glia-expressed genes are diverse and include a G protein-coupled receptor (CG4322), an esterase (Gli), a metallopeptidase (CG6225), and a transporter (CG3168).

The two mature DM cells in each segment are mesodermal derivatives that lie above the CNS (Fig. 1F). DM cells are associated with the midline channel and, thus, reside between the posterior commissure and the anterior commissure of the next ganglion. The DM cells extend a process to the body wall muscle attachment sites. CNS motorneurons and neurosecretory cells that form the transverse nerve use these processes to navigate toward their muscle synaptic targets (Chiang et al., 1994). The formation of mature DM cells is dependent on an unknown signal from the CNS midline cells (Luer et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 1997). The paired DM cells are easily identified based on their number, position atop the CNS, and characteristic morphology. These cells are noted for their expression of the buttonless gene (Chiang et al., 1994) and, like channel glia, numerous genes encoding basement membrane components (Fessler and Fessler, 1989). In our AP screen, 10 genes were expressed in the DM cells (Table 1; Fig. 6E–F), including the TE 412 transposable element (Fig. 6G). The genes expressed in DM cells are varied, including two transcription factors (zfh1 and CG12648), a cell adhesion protein (fas1), a protease (Mmp1), a basement membrane component (prc), a G protein-coupled receptor (CG4322), and a transporter (CG4726).

Transposable elements

There are 96 families of transposable elements in Drosophila, constituting 1596 individual elements (Kaminker et al., 2002). Analysis of midline-expressed enhancer trap lines revealed 11 independent insertions into seven families of transposable elements. We believe the enhancer traps are recapitulating the expression of transposable elements and not nearby genes because 10/11 lines show P-element insertion into the body of the transposable element within the putative coding sequence. Other sources implicated midline expression of four additional transposable element families. Of these 11 total transposable element families, we analyzed seven by in situ hybridization. Six showed prominent midline expression (Table 1; Fig. 6G–H), and one did not. Since probes were used for each transposable element that would cross-hybridize with many or all members of the family, midline expression is likely to be from multiple members of the family, not just the element containing the enhancer trap insertion. Midline expression of transposable elements is diverse: TE 412 is expressed in DM cells (Fig. 6G), TE Beagle in midline neurons and glia (Lammel and Klambt, 2001) and TE copia (Fig. 6H), TE 1371, TE Doc, and TE Rt1a in midline neurons. TE 412 and TE Doc are also expressed in the midline primordium. While the significance of transposable element midline expression is unknown, it appears to be relatively widespread and may serve a function in the evolution of transcriptional regulation (Bennetzen, 2000).

High-resolution identification of midline gene expression

One of the long-term goals that will assist genetic analysis of midline cell development and function is to determine the expression of each midline-expressed gene at the single cell level. This currently involves the use of cellular markers that unambiguously identify specific midline cell types, multi-label fluorescent staining, and confocal microscopy. Previous studies have identified midline cell types based on the position of cell bodies and, in the case of neurons, axonal morphology (Bossing and Technau, 1994; Schmid et al., 1999). Here we demonstrate how in situ hybridization can be systematically employed with appropriate midline cell markers to localize midline gene expression to specific mature midline cell types. Transgenic fly strains that drive expression of Gal4 in subsets of midline neurons and glia are particularly useful since they can be combined with UAS reporter genes that allow visualization of nuclei, cytoplasm, or axons. The Gal4 strains include MzVUM-Gal4 (VUM motorneurons), C544-Gal4 (MP1 neurons), and slit-Gal4 (anterior and posterior midline glia) (Landgraf et al., 2003; Scholz et al., 1997). When crossed to UAS reporters and double-labeled, we can correlate the neuronal or glial cell bodies directly with midline gene expression. In these experiments, we also use En antibody staining to mark the VUM interneurons and several progeny of the MNB (Jia and Siegler, 2002).

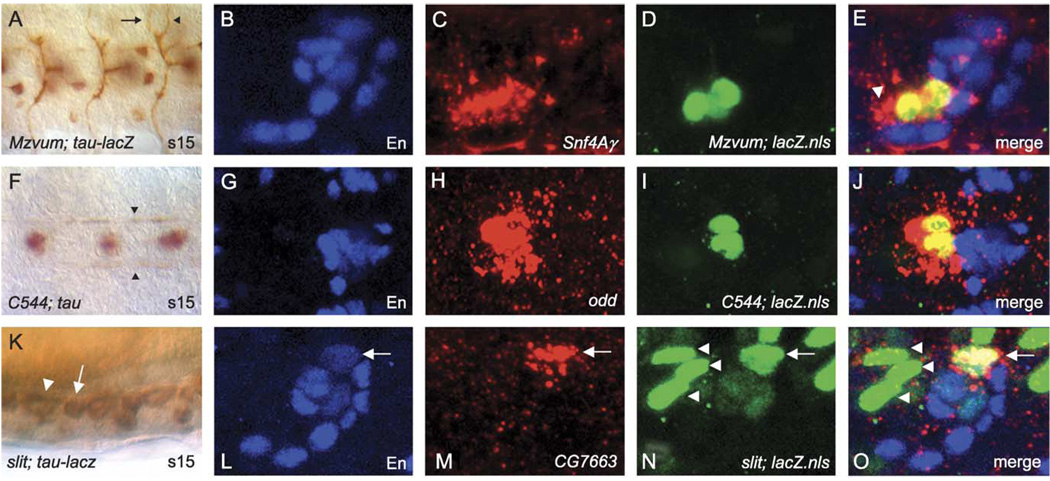

MzVUM-Gal4 × UAS-tau-lacZ stains the soma of the three motorneuronal VUM neurons, which are also En-negative (Siegler and Jia, 1999), as confirmed by visualization of the characteristic motorneuronal axonal trajectories (Fig. 7A) (Bossing and Technau, 1994; Landgraf et al., 1997; Sink and Whitington, 1991). In our AP staining experiments, we identified Snf4Ay as expressed in ventral neurons (Fig. 5I). When MzVUM-Gal4 × UAS-GFP-lacZ.nls embryos are immunostained for En and β-gal, and hybridized to Snf4Ay, we observed overlap between Snf4Ay and lacZ expression, but not En (Fig. 7B–E). This demonstrates that Snf4Ay is expressed in the three VUM motorneurons and not the VUM interneurons. Additional Snf4Ay expression anterior to the motorneuronal VUM staining may be localized to one or both of the MP3 progeny.

Fig. 7.

Cellular correspondence of midline gene expression. (A, F, K) DIC images of Gal4×UAS-tau or UAS-tau-lacZ embryos immunostained with anti-Tau or anti-β-gal. (B–E, G–J, L–O) Confocal images showing midline cell co-localization of RNA probes with defined midline cell markers. Anterior is to the left in all cases, and for sagittal views, dorsal is up. (A) Ventral view of stage 15 MzVUM-Gal4×UAS-tau-lacZ embryo showing the VUM motorneuron axonal trajectories that project out the intersegmental (arrow) and segmental (arrowhead) nerve roots. The VUM motorneuron cell bodies are out of the plane of focus. (B–E) Sagittal view of an individual ganglion from a MzVUM-Gal4×UAS-GFP-lacZ.nls embryo stained for (B) anti-En (blue), (C) Snf4Ay RNA (red), (D) anti-β-gal (green), and (E) merge image showing that Snf4Ay RNA co-localizes with β-gal-stained VUM motorneurons. Additional expression is detected just anterior to VUM motorneurons (arrowhead) and may represent staining in MP3 neurons. (F) Ventral view of a stage 15 C544-Gal4×UAS-tau embryo stained with anti-Tau showing the MP1 axonal trajectories along the longitudinal connectives (arrowheads). (G–J) Ventral view of an individual ganglion from a stage 16 C544-Gal4×UAS-GFP-lacZ.nls embryo stained for (G) anti-En (blue), (H) odd RNA (red), (I) anti-β-gal (green), and (J) merge image showing that odd RNA co-localizes with β-gal-stained MP1 neurons. (K) Sagittal view of stage 15 slit-gal4×UAS-tau-lacZ embryo showing anterior (arrowhead) and posterior (arrow) glia within a single ganglion. (L–O) Sagittal view of a single ganglion from a slit-Gal4×UAS-GFP-lacZ.nls embryo stained for (L) anti-En (blue), (M) CG7663 RNA (red), (N) anti-β-gal (green), and (O) merge image showing that CG7663 RNA co-localizes with β-gal and En-stained posterior glia (arrow). Posterior glia (arrow) can be easily distinguished from the three anterior glia (arrowheads) based on their relative positions along the A–P axis.

C544-Gal4 × UAS-tau labels two MP1 neurons, as identified by their unique interneuronal projections (Fig. 7F). In C544-Gal4 × UAS-GFP-lacZ.nls embryos, we observe colocalization of the MP1 β-gal stain with the expression of odd (Fig. 7G–J), a gene we determined by AP staining to be expressed in medial neurons (Fig. 5L). This result proves the expression of odd in MP1 neurons, as previously proposed (Spana et al., 1995).

Both anterior and posterior midline glia can be visualized using a Gal4 transgene driven by the slit promoter (Fig. 7K) (Wharton and Crews, 1993). In our AP expression screen, we classified CG7663 as expressed prominently in posterior midline glia (Fig. 4K–L). Using slit-gal4 driving the expression of UAS-GFP-lacZ.nls, we confirmed CG7663 expression co-localized with slit-Gal4 in the posterior glia (Fig. 7L–O). Interestingly, the CG7663 expression also co-localizes with En, indicating that at least a subset of posterior glia express both En and slit (Fig. 7L–O). These results indicate that the use of appropriate makers and imaging techniques can unambiguously identify distinct midline cell types. Extending this type of analysis to all midline-expressed genes will allow for the creation of a comprehensive molecular map of midline cell development.

Discussion

To begin a detailed analysis of the development and function of the Drosophila CNS midline cells, we assembled a database containing genes likely to be expressed in midline cells. In this report, we cataloged the expression patterns of 282 genes at each stage of CNS development and demonstrated midline cell expression for 224 (80%). These include (1) previously identified as well as novel genes; (2) genes expressed in all or most midline cells; (3) genes expressed in specific midline cell types, including subsets of midline progenitors; and (4) genes expressed in midline accessory cells. These data together with the genetic and genomic resources available in Drosophila provide a strong foundation for the future study of CNS midline cells.

A database of midline-expressed genes

The overall goal of this project is to study the development and function of the CNS midline cells as a model for understanding the molecular and genetic control of neural and glial cell development and function. There are a number of attractive reasons for studying CNS midline cell development: (1) midline cells occupy a discrete location within the embryo and are made up of diverse cell types, including interneurons, motorneurons, and glia; (2) midline cells have many developmental roles; (3) genes expressed in midline cells are particularly easy to identify based on their unique stripe of expression along the A/P axis of the embryo; and (4) there are a number of existing genes known to control aspects of their development and function.

To harness the full utility of this neurodevelopmental model system, we have begun to establish a comprehensive molecular map of CNS midline cell development. At the level of resolution of AP in situ hybridization, we were able to subdivide gene expression in mature midline cells into two neuronal categories (ventral and medial), two glial categories (anterior and posterior), and three accessory cell types. We have also demonstrated, using the Gal4/UAS system, in combination with fluorescent in situ hybridization and confocal analysis, that we can determine the extent of midline gene expression at the single cell level. These technologies together with the relatively simple organization of the CNS midline cells will allow the expression of each gene in the midline database to be assigned to specific midline cell types at each stage of development. Once assembled, this molecular map of gene expression will allow large-scale neurogenetic analysis in which scores of genes can be examined simultaneously in mutant or RNAi embryos that show defects in midline cell development, gene expression, or function. Since co-expressed genes have the potential to biochemically and genetically interact, the molecular map will likely be useful in predicting gene regulatory and protein–protein interactions that can be tested directly or cross-referenced with existing Drosophila protein and genetic interaction databases (Breitkreutz et al., 2003; Giot et al., 2003).

Using recent data that estimate the total number of Drosophila genes at ~16,000 (Hild et al., 2003) and the percentage of midline expressed genes compared to total examined (3%) from the BDGP expression database (Tomancak et al., 2002), we estimate that, in total, ~480 genes will be expressed in the CNS midline cells. These estimates indicate that we have already identified the expression patterns of roughly half of all genes expressed in midline cells. Thus, the continued analysis of gene expression patterns during Drosophila embryogenesis, both by individual labs and large-scale genome projects, will likely identify all CNS midline-expressed genes in the near future. With the completion of a comprehensive molecular map, the Drosophila CNS midline cells will be an excellent system for neurogenomic research given the large number of genes identified, the detailed view of their expression, and the advantages of Drosophila as an organism for molecular genetic research.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank undergraduate researchers Marce Abare, Lara Andrachuk, and Jenny Woodard, and high school researchers, JaShaun Peele and Natalie Rubinstein for invaluable contributions to this project. We would also like to thank Tony Perdue for assistance with confocal microscopy, Mike Vernon (UNC Neuroscience Center Functional Genomics Core Facility) for assistance with microarray experiments, the UNC-CH Genome Analysis Facility, and Lan Jiang and Dan Lau for technical advice. We are grateful to Corey Goodman, Christine Uemura, Andrea Brand, Ulrike Gaul, Paul Hardin, Jay Hirsh, Roger Jacobs, Wilfred Janning, Nipam Patel, Andreas Prokop, Melody Siegler, and Gerd Technau for contributing reagents, fly stocks, and advice. This work was supported by NIH grant RD25251 to STC.

References